Research on the Complex Network Structure and Spatiotemporal Evolution of Interprovincial Virtual Water Flows in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Construction and Data Sources

2.1. Construction of a Multi-Region Input–Output Model

2.2. Construction of Complex Network Analysis Models

2.3. Exploratory Spatio-Temporal Data Analysis

2.3.1. LISA Time Path

2.3.2. LISA Spacetime Transition

2.4. Data Sources and Analytical Tools

2.4.1. Data Sources

2.4.2. Analytical Tools

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Interprovincial Virtual Water Flow Patterns in China

3.2. Topological Characteristics and Key Node Identification in Virtual Water Flow Network Structures

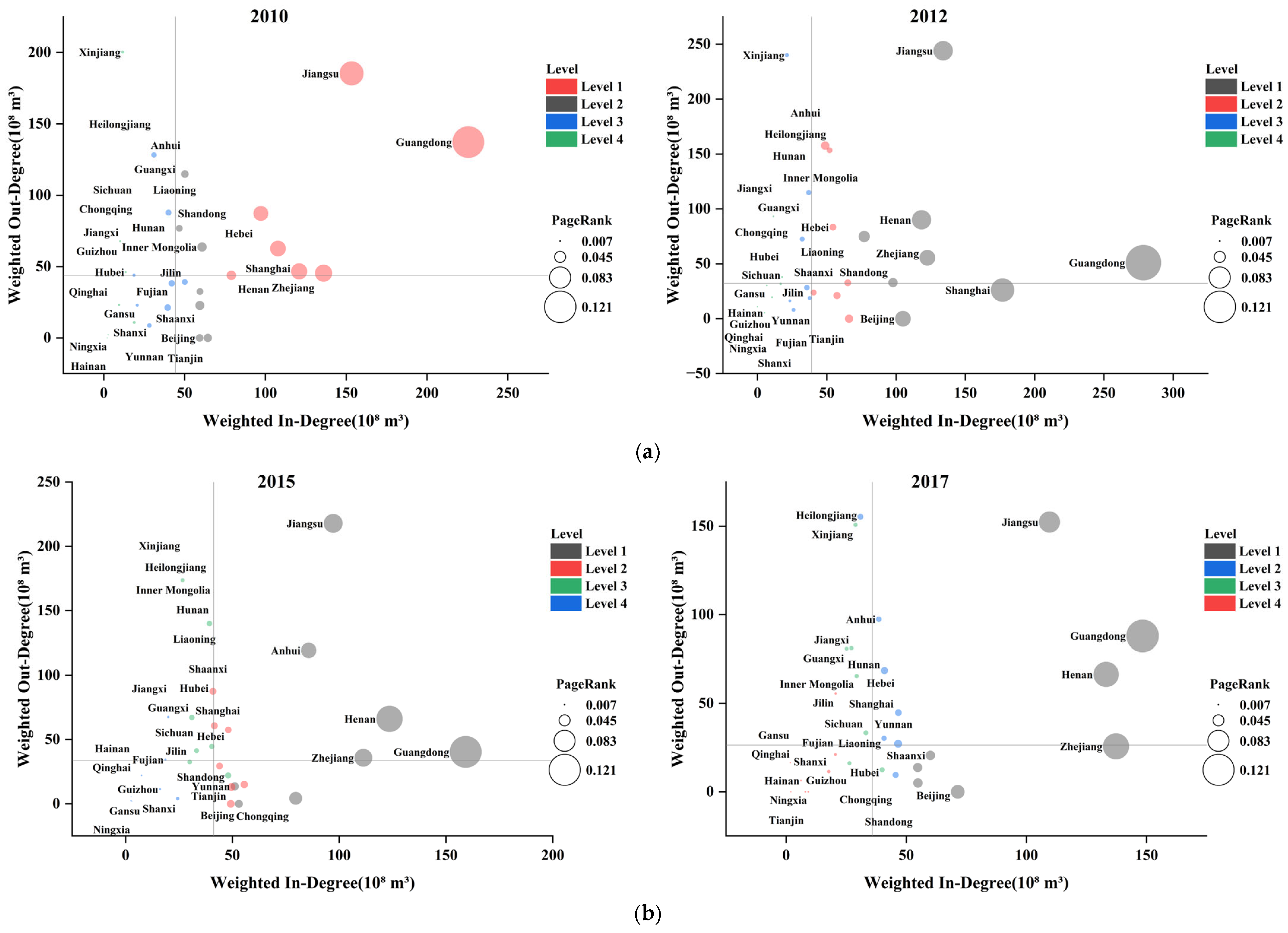

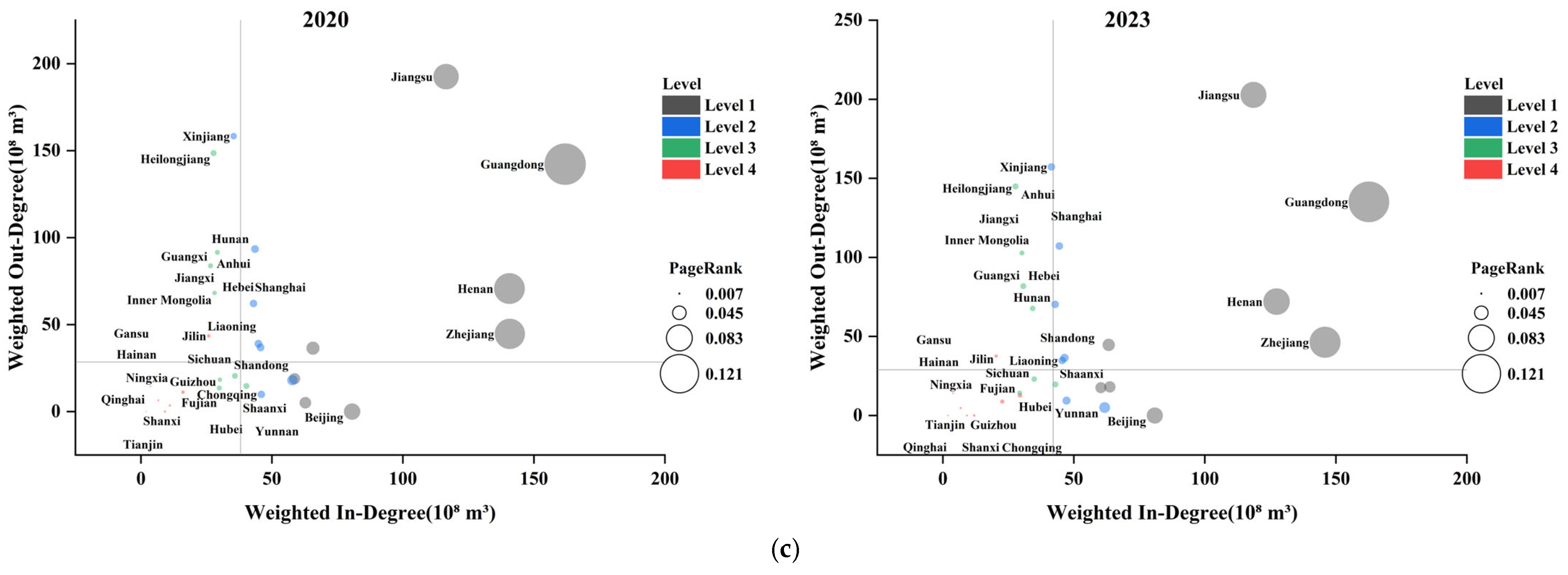

3.3. Combined with PageRank Analysis

3.4. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Virtual Water Inflows and Outflows Across Chinese Provinces

3.4.1. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Virtual Water Flow Between Chinese Provinces

- (1)

- The temporal dynamics of virtual water outflow are significantly higher than those of inflow

- (2)

- Identification of Spatiotemporal Dynamic Characteristics in Key Provinces

- (3)

- Spatial–Temporal Evolutionary Differences in Regional Agglomeration Patterns

3.4.2. Temporal-Spatial Migration Analysis

4. Research Findings and Policy Recommendations

4.1. Research Findings

- (1)

- The scale of virtual water flows exhibited a distinct three-phase evolution: an “expansion phase” (2010–2015) that accompanied deepened regional integration, a “policy regulation phase” (2015–2020) characterized by convergence, which corresponded to the period of the dual-control policy on water resources, and a “stabilization and optimization phase” (2020–2023). Spatially, a stable “core–periphery” structure emerged, with eastern coastal and North China urban clusters acting as primary input hubs, and East, Northeast, and Northwest China serving as key output regions.

- (2)

- Corresponding to these flow dynamics, the virtual water flow network became progressively tighter and more segmented. Key topological metrics indicated enhanced connectivity and efficiency: network density and transitivity increased, while the average shortest path length decreased. The rising clustering coefficient signaled the formation of tightly knit regional subgroups. PageRank analysis revealed significant Matthew effects and structural lock-in, with core provinces (Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang) maintaining dominant influence while peripheral provinces (Qinghai, Gansu) remained marginalized.

- (3)

- LISA time path analysis indicated that while most provinces exhibited stable local spatial structures, certain key nodes (Guangdong, Jiangsu) demonstrated high spatiotemporal dynamism, characterized by elevated relative length and curvature. This suggests their heightened sensitivity to policy adjustments, industrial transformation, and regional interactions.

- (4)

- The system demonstrated considerable overall resilience. LISA spatiotemporal transition analysis showed that Type0 transitions (no change in local spatial type) accounted for 47% of all observations. The fact that Type2 transitions significantly outnumbered Type1 (own change) underscores that spatial reorganization is often a coordinated process within regional neighborhoods, rather than an isolated provincial phenomenon.

4.2. Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Implement Node-Specific Management within the Virtual Water Network. Governance should be tailored to the distinct functions of different network nodes. For core consumption hubs (Guangdong, Zhejiang), promote demand-side management and industrial upgrading towards lower water-intensity sectors. For major production-supply hubs (Xinjiang, Heilongjiang), strengthen ecological compensation and water-saving incentives to ensure the sustainability of their virtual water exports. This approach addresses the observed functional differentiation and structural lock-in.

- (2)

- Adopt Differentiated Regional Strategies Based on Spatiotemporal Dynamics. For highly dynamic provinces (Guangdong, Jiangsu), establish real-time monitoring and early warning systems to preempt risks from sudden shifts in virtual water pathways. For stable, low-dynamic western provinces, policies should focus on overcoming path dependence by fostering specialized industries and improving regional connectivity to integrate them more effectively into the national network.

- (3)

- Enhance Institutional Resilience through Market-Government Coordination. Deepen the reform of water rights trading and cross-regional ecological compensation mechanisms. Establishing a virtual water compensation framework at the basin and regional levels can help clarify the responsibilities of producers and consumers, creating a fairer virtual water trade order. This aligns with the finding that systemic resilience is high but can be bolstered by addressing the inherent external dependencies of consumption hubs.

- (4)

- Integrate Virtual Water Flows into Major Regional Development Strategies. In national strategies like the Yangtze River Delta integration and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area development, industrial planning should explicitly account for the evolution of virtual water flow patterns. Encouraging technological spillovers and industrial cooperation from eastern to central and western regions can help improve water use efficiency nationwide, thereby mitigating the spatial imbalances identified in the “core–periphery” structure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Region | Total Outflow of Virtual Water | Total Inflow of Virtual Water 108 m3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2012 | 2015 | 2017 | 2020 | 2023 | 2010 | 2012 | 2015 | 2017 | 2020 | 2023 | |

| Beijing | 10.2 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 78.7 | 112.7 | 66.7 | 78.4 | 89.8 | 89.6 |

| Tianjin | 11.1 | 9.0 | 8.4 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 77.6 | 82.2 | 61.6 | 21.6 | 25.1 | 25.2 |

| Hebei | 102.1 | 95.2 | 66.1 | 57.9 | 56.6 | 53.4 | 106.0 | 73.0 | 62.4 | 59.5 | 60.8 | 60.6 |

| Shanxi | 23.2 | 28.7 | 26.6 | 23.5 | 23.6 | 22.2 | 49.5 | 43.9 | 39.1 | 29.4 | 31.3 | 37.0 |

| Inner Mongolia | 77.2 | 89.4 | 69.5 | 72.6 | 77.9 | 77.4 | 72.5 | 88.5 | 53.6 | 42.6 | 42.5 | 48.6 |

| Liaoning | 45.8 | 55.4 | 43.4 | 46.1 | 51.7 | 49.1 | 74.6 | 83.1 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 56.6 | 56.4 |

| Jilin | 50.2 | 48.6 | 46.6 | 65.6 | 58.2 | 54.9 | 66.1 | 52.1 | 45.8 | 37.5 | 41.4 | 37.8 |

| Heilongjiang | 138.5 | 159.1 | 144.2 | 157.8 | 150.9 | 147.2 | 45.4 | 69.7 | 51.4 | 41.2 | 40.6 | 40.6 |

| Shanghai | 60.6 | 46.9 | 37.9 | 45.1 | 52.4 | 57.1 | 129.7 | 178.7 | 68.6 | 56.9 | 73.4 | 72.3 |

| Jiangsu | 188.2 | 245.9 | 220.2 | 155.7 | 194.7 | 205.2 | 159.4 | 138.7 | 100.6 | 114.8 | 122.2 | 124.2 |

| Zhejiang | 64.2 | 70.4 | 46.5 | 43.3 | 59.6 | 60.0 | 145.3 | 132.2 | 118.0 | 140.9 | 144.7 | 149.7 |

| Anhui | 128.0 | 160.4 | 121.6 | 102.6 | 99.9 | 113.0 | 63.2 | 66.3 | 93.3 | 51.0 | 56.9 | 57.7 |

| Fujian | 55.6 | 42.2 | 49.0 | 37.5 | 37.9 | 33.1 | 58.4 | 54.0 | 35.1 | 32.3 | 42.1 | 43.4 |

| Jiangxi | 83.9 | 103.7 | 73.5 | 87.8 | 99.0 | 109.3 | 28.2 | 31.6 | 35.6 | 41.1 | 43.6 | 45.0 |

| Shandong | 55.5 | 56.5 | 40.6 | 31.3 | 39.4 | 37.3 | 90.3 | 112.4 | 61.7 | 63.6 | 69.3 | 71.0 |

| Henan | 77.9 | 97.6 | 73.1 | 73.1 | 76.3 | 77.7 | 113.9 | 125.5 | 128.4 | 137.8 | 143.9 | 135.0 |

| Hubei | 62.9 | 48.9 | 53.7 | 30.7 | 32.1 | 39.5 | 35.0 | 37.6 | 55.1 | 51.7 | 52.3 | 55.2 |

| Hunan | 100.1 | 121.6 | 90.6 | 73.1 | 71.2 | 76.8 | 53.5 | 52.9 | 56.8 | 56.5 | 60.0 | 59.3 |

| Guangdong | 143.1 | 67.2 | 52.8 | 92.6 | 144.3 | 138.7 | 232.0 | 281.8 | 161.6 | 151.5 | 163.8 | 166.1 |

| Guangxi | 88.6 | 85.3 | 73.6 | 87.4 | 89.2 | 89.2 | 61.8 | 54.0 | 45.3 | 39.1 | 42.8 | 43.6 |

| Hainan | 11.9 | 22.8 | 20.3 | 21.2 | 22.0 | 22.3 | 7.8 | 20.2 | 16.2 | 18.9 | 19.7 | 20.7 |

| Chongqing | 32.6 | 41.7 | 21.6 | 28.9 | 30.3 | 29.7 | 37.3 | 43.2 | 86.9 | 58.7 | 63.0 | 62.2 |

| Sichuan | 57.3 | 54.8 | 52.7 | 47.0 | 41.7 | 44.0 | 43.4 | 40.7 | 44.7 | 47.0 | 52.7 | 53.3 |

| Guizhou | 39.9 | 37.6 | 30.6 | 34.7 | 32.5 | 34.9 | 30.0 | 29.1 | 33.5 | 41.6 | 46.6 | 45.2 |

| Yunnan | 43.8 | 45.0 | 32.2 | 21.8 | 22.1 | 22.3 | 54.1 | 57.6 | 64.7 | 66.4 | 75.5 | 76.0 |

| Shaanxi | 43.2 | 38.4 | 32.1 | 36.9 | 38.7 | 39.3 | 73.5 | 72.7 | 62.3 | 69.5 | 70.5 | 75.5 |

| Gansu | 42.0 | 53.3 | 42.0 | 34.8 | 31.4 | 30.6 | 33.7 | 22.7 | 22.6 | 17.4 | 18.5 | 19.6 |

| Qinghai | 11.4 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 12.1 | 8.4 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 9.4 |

| Ningxia | 25.2 | 31.4 | 26.6 | 14.8 | 18.1 | 16.3 | 14.9 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 23.0 | 24.0 | 26.3 |

| Xinjiang | 202.1 | 242.4 | 176.0 | 152.2 | 158.3 | 158.7 | 28.5 | 41.3 | 42.0 | 43.9 | 48.2 | 53.7 |

References

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, N.T.; Hejazi, M.I.; Kim, S.H.; Davies, E.G.R.; Edmonds, J.A.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Future changes in the trading of virtual water. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.R.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; van Vliet, M.T.H. Current and future global water scarcity intensifies when accounting for surface water quality. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Fan, Y.; Fang, C. Virtual water network evolution and its uneven effects on water stress across China’s urban agglomerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 526, 146692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zi, T.; Wang, L.; Cao, X. Analysis of crop virtual water flow at dual scales in yellow river basin based on the SWAT model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, Q.; Tian, G.; Xia, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wan, X. Resilience assessment of city-level virtual water flow network in the Yellow River Basin, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhuo, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; Wu, P. Resilience assessment of interprovincial crop virtual water flow network in China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Long, A.; Han, X.; Lai, X.; Meng, Y. Analysis of agricultural water security based on network invulnerability: A case study in China’s virtual water trade networks. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Engel, B.A.; Tian, X.; Sun, S.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y. Evaluating drivers and flow patterns of inter-provincial grain virtual water trade in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, M.; Wu, M.; Luan, X.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z. Influences of the south–to-north water diversion project and virtual water flows on regional water resources considering both water quantity and quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Su, B.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Interprovincial transfer of embodied primary energy in China: A complex network approach. Appl. Energy 2018, 215, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; An, H.; Gao, X.; Jia, X.; Liu, X. Indirect energy flow between industrial sectors in China: A complex network approach. Energy 2016, 94, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, X.Y.; Feng, L. The driving force of water resource stress change based on the STIRPAT model: Take Zhangye City as a case study. Sci. Cold Arid. Reg. 2021, 13, 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Li, J.S.; Wu, X.F.; Han, M.Y.; Zeng, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, G.Q. Global energy flows embodied in international trade: A combination of environmentally extended input–output analysis and complex network analysis. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Gao, X.; Guan, Q.; Hao, X.; An, F. The structural roles of sectors and their contributions to global carbon emissions: A complex network perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Song, J.; Di, X.; Wang, R. Structural evolution of China’s intersectoral embodied carbon emission flow network. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 21145–21158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Tang, M.; Wu, Z.; Miao, Z.; Shen, G.Q. The evolution of patterns within embodied energy flows in the Chinese economy: A multi-regional-based complex network approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.; Yu, J.; Deng, X.; He, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Ren, C.; Du, J. Understanding the spatial-temporal changes of oasis farmland in the Tarim River Basin from the perspective of agricultural water footprint. Water 2021, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Marsafawy, S.M.; Mohamed, A.I. Water footprint of Egyptian crops and its economics. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 4711–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhuo, L.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Feng, B.; Wu, P. Quantitative evaluation of spatial scale effects on regional water footprint in crop production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrien, M.M.; Aldaya, M.M.; Rodriguez, C.I. Water footprint and virtual water trade of maize in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Water 2021, 13, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamea, S.; Tuninetti, M.; Soligno, I.; Laio, F. Virtual water trade and water footprint of agricultural goods: The 1961–2016 CWASI database. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2020, 13, 2025–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yi, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, K.; Zhen, J. What network roles affect the decline of the embodied carbon emission reduction pressure in China’s manufacturing sector foreign trade? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Dong, G.; Tian, L.; Kong, Z.; Ahsan, M. Evaluation of key node groups of embodied carbon emission transfer network in China based on complex network control theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Ren, F.; Zhu, R.; Wang, P.; Du, T.; Du, Q. Analysing the spatial configuration of urban bus networks based on the geospatial network analysis method. Cities 2020, 96, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jin, X.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Y. Quantifying the spatiotemporal dynamics and impact factors of China’s county-level carbon emissions using ESTDA and spatial econometric models. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 410, 137203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnini, C.; Vieira, L.C.; Longo, M.; Mura, M. Chasing net zero: An exploratory space-time analysis of European regions’ industrial carbon emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, D.; He, H.; Liu, C.; Han, S. Spatio-temporal dynamic evolution of carbon emissions from land use change in Guangdong Province, China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.J. Spatial empirics for economic growth and convergence. Geogr. Anal. 2001, 33, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.J.; Janikas, M.V. STARS: Space-time analysis of regional systems. In Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Qu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Song, X.; Zhao, M.; Han, R. Driving mechanism of urban expansion in the Bohai Rim urban agglomeration from the perspective of spatiotemporal dynamic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.; Murray, A. Alternative input-output matrix updating formulations. Econ. Syst. Res. 2004, 16, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y. Understanding the structure and determinants of intercity carbon emissions association network in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 352, 131535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Network Metrics | Formula for Calculation | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Density | (9) | Reflects the density of connections between nodes in a network. Here, L represents the actual number of edges in the network, N denotes the total number of nodes, and N (N − 1) signifies the maximum possible number of relationships. | |

| Clustering Coefficient | (10) | Reflects the local clustering tendency of the network. Higher values indicate the presence of multiple closely connected trade groups. Ei is the actual number of edges between neighbors of node i, and ki is the degree of node i. | |

| Average Shortest Path Length | (11) | Measuring the overall efficiency of virtual water flow. A shorter path implies fewer intermediary stages in resource circulation. dij is the number of edges in the shortest path from node i to node j. | |

| Transitivity | (12) | Measuring closed-loop structures within networks. Higher values indicate stronger reciprocity and stability within the network. | |

| Weighted In-Degree | (13) | This indicator quantifies the scale of a province as a virtual water inflow hub. Higher values indicate greater external dependency. Fij represents the volume of virtual water flowing from province j to province i. | |

| Weighted Out-Degree | (14) | Quantify the scale of provinces as virtual water export hubs. Higher values indicate stronger external supply capacity. Fij represents the virtual water flow from province i to province j. |

| Notation | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| D | Network Density | Dimensionless |

| L1 | The actual number of edges in the network | Dimensionless (Count) |

| N | Total number of nodes | Dimensionless (Count) |

| C | Clustering Coefficient | Dimensionless |

| Ei | The actual number of edges between neighbors of node i | Dimensionless (Count) |

| ki | Degree of node i (number of edges) | Dimensionless (Count) |

| L2 | Average Shortest Path Length | Dimensionless (Count) |

| dij | The number of edges in the shortest path from node i to node j | Dimensionless (Count) |

| T | Transitivity | Dimensionless |

| Fji | Virtual water flow from province j to province i | 108 m3 |

| Fij | Virtual water flow from province i to province j | 108 m3 |

| Weighted In-degree of node i | 108 m3 | |

| Weighted Out-degree of node i | 108 m3 |

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Type0 | Neither the province itself nor any of its neighboring provinces experienced a transition in any of the local types. |

| Type1 | A certain province undergoes a transition, but the types of its neighboring provinces remain unchanged. |

| Type2 | A certain province remains unchanged in its own classification, but its neighboring provinces undergo a transition. |

| Type3 | The province itself and its neighboring provinces have all undergone a type of transition. |

| Year | Number of Edges | Network Density | Average Shortest Path Length | Average Clustering Coefficient | Transitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 341 | 0.392 | 1.679 | 0.624 | 0.750 |

| 2011 | 346 | 0.398 | 1.685 | 0.608 | 0.785 |

| 2012 | 363 | 0.447 | 1.521 | 0.653 | 0.785 |

| 2013 | 370 | 0.456 | 1.501 | 0.672 | 0.807 |

| 2014 | 371 | 0.457 | 1.495 | 0.663 | 0.807 |

| 2015 | 389 | 0.479 | 1.525 | 0.685 | 0.804 |

| 2016 | 368 | 0.453 | 1.500 | 0.649 | 0.790 |

| 2017 | 368 | 0.423 | 1.558 | 0.668 | 0.800 |

| 2018 | 368 | 0.423 | 1.552 | 0.676 | 0.785 |

| 2019 | 367 | 0.422 | 1.556 | 0.677 | 0.775 |

| 2020 | 366 | 0.421 | 1.554 | 0.685 | 0.772 |

| 2021 | 367 | 0.422 | 1.552 | 0.667 | 0.772 |

| 2022 | 369 | 0.424 | 1.549 | 0.695 | 0.784 |

| 2023 | 365 | 0.420 | 1.537 | 0.694 | 0.772 |

| Indicator | Virtual Water Outflow Average | Average Virtual Water Inflow |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Length | 1.02 | 0.95 |

| Curvature | 5.24 | 2.69 |

| 2010–2023 Spatiotemporal Transition Matrix of Provincial-Level Virtual Water Inflows/Outflows in China Using Local Moran’s I | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | Year t/Year t + 1 | HH | LH | LL | HL | Type | Quantity | Proportion | SF | SC | p |

| Total outflow of virtual water | HH | 0.76 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.19 | Type0 | 71 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.17 |

| LH | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.11 | 0.00 | Type1 | 9 | 0.06 | ||||

| LL | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.00 | Type2 | 57 | 0.38 | ||||

| HL | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.78 | Type3 | 13 | 0.09 | ||||

| Total inflow of virtual water | HH | 0.70 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.19 | Type0 | 70 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.17 |

| LH | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Type1 | 6 | 0.04 | ||||

| LL | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.05 | Type2 | 58 | 0.39 | ||||

| HL | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.80 | Type3 | 16 | 0.11 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, C. Research on the Complex Network Structure and Spatiotemporal Evolution of Interprovincial Virtual Water Flows in China. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021090

Song Q, Chen H, Yang C. Research on the Complex Network Structure and Spatiotemporal Evolution of Interprovincial Virtual Water Flows in China. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021090

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Qing, Hongyan Chen, and Chuanming Yang. 2026. "Research on the Complex Network Structure and Spatiotemporal Evolution of Interprovincial Virtual Water Flows in China" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021090

APA StyleSong, Q., Chen, H., & Yang, C. (2026). Research on the Complex Network Structure and Spatiotemporal Evolution of Interprovincial Virtual Water Flows in China. Sustainability, 18(2), 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021090