Healthcare Decarbonisation Education for Health Profession Students: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

- To identify and examine the current literature on educational strategies for teaching healthcare decarbonisation to pre-registration health profession students.

- To explore the content and effectiveness of different educational resources in relation to student outcomes.

- To map the evidence on pedagogical approaches to healthcare decarbonisation education for pre-registration health profession students to inform the co-design of an educational resource on healthcare decarbonisation.

- To identify any gaps in existing research regarding healthcare decarbonisation education for pre-registration health profession students.

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3.1. Types of Sources

2.3.2. Population, Concept, and Context (PCC) Framework

2.4. Search Strategy

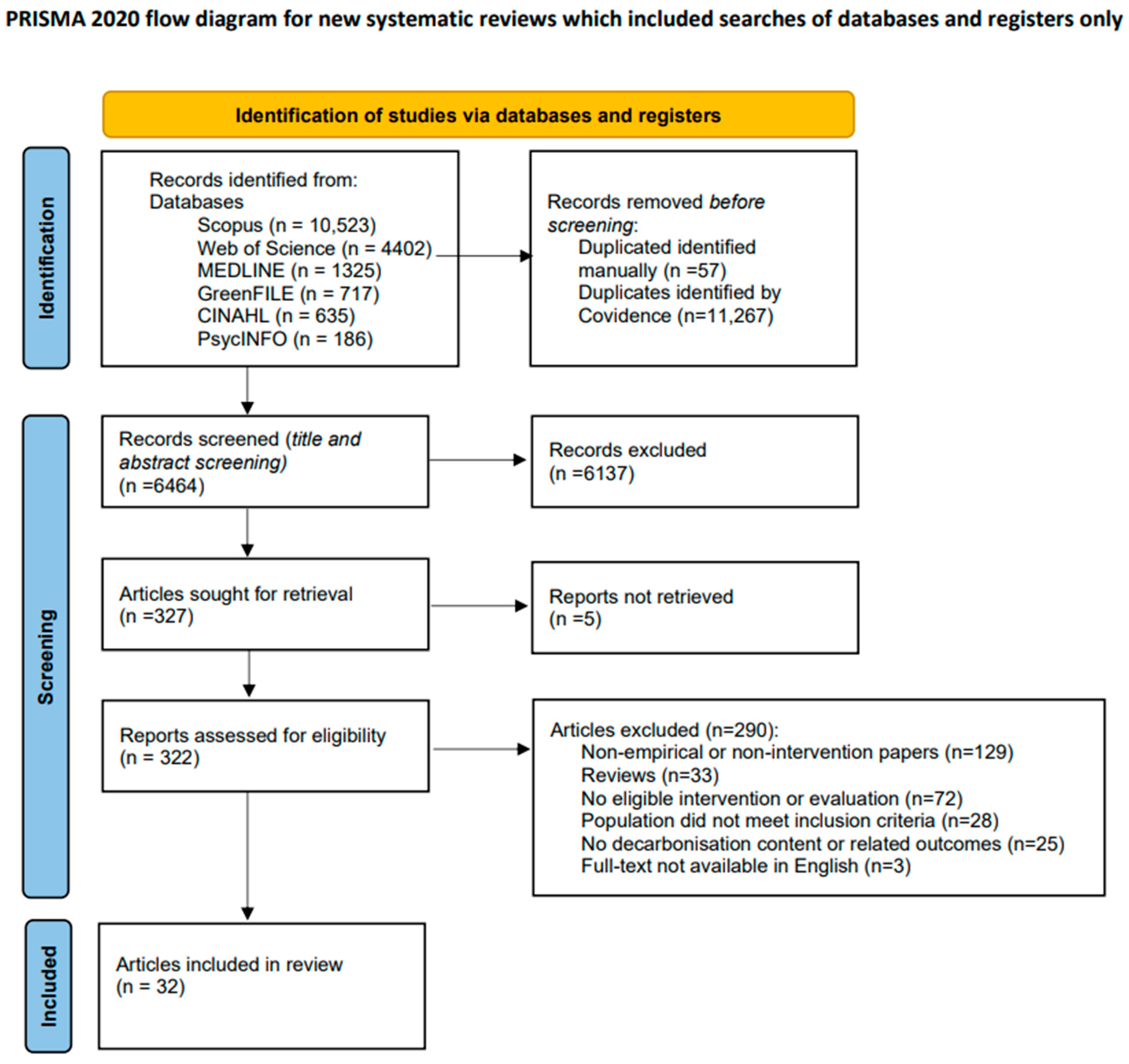

Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis and Reporting

3. Results

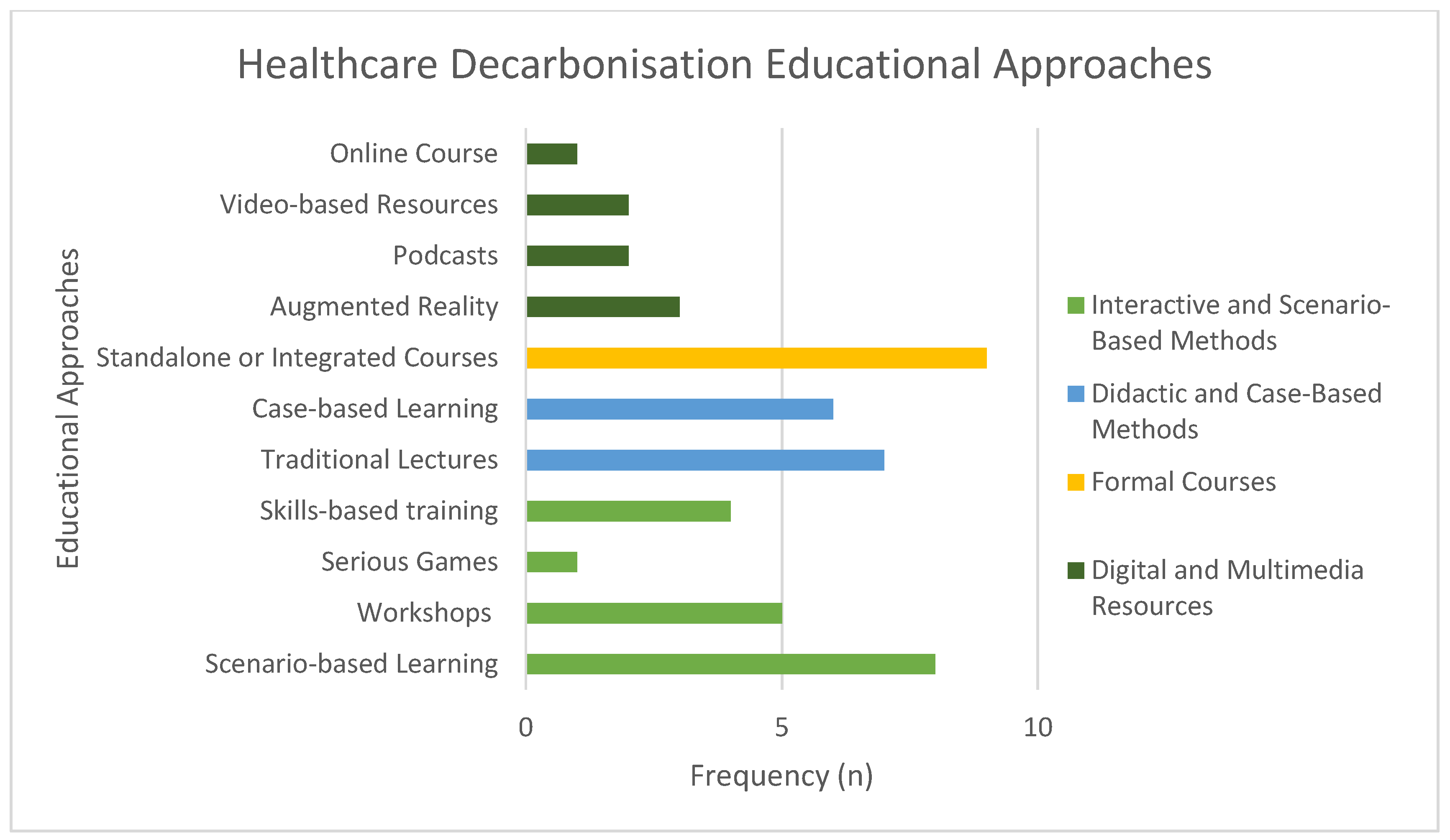

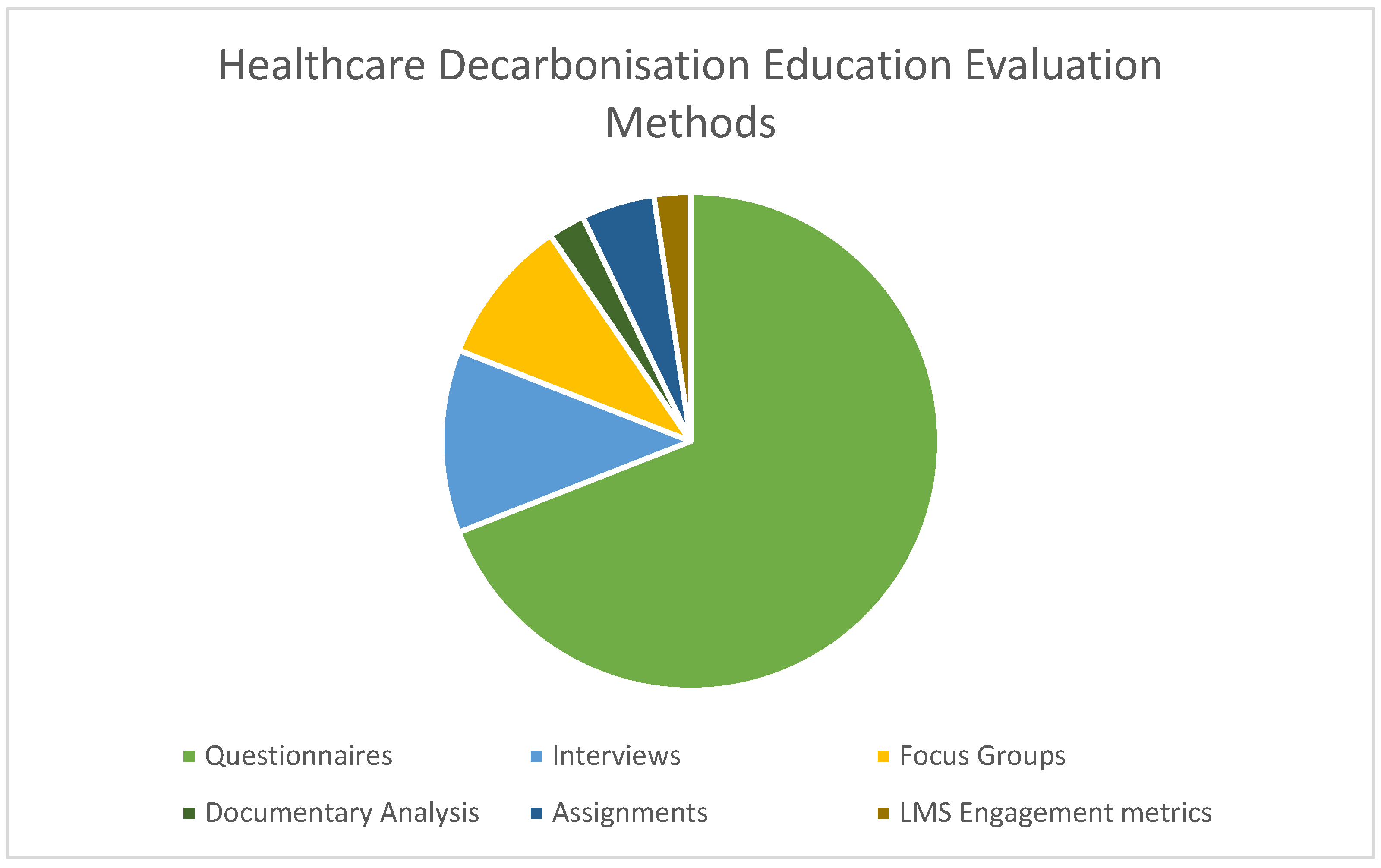

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

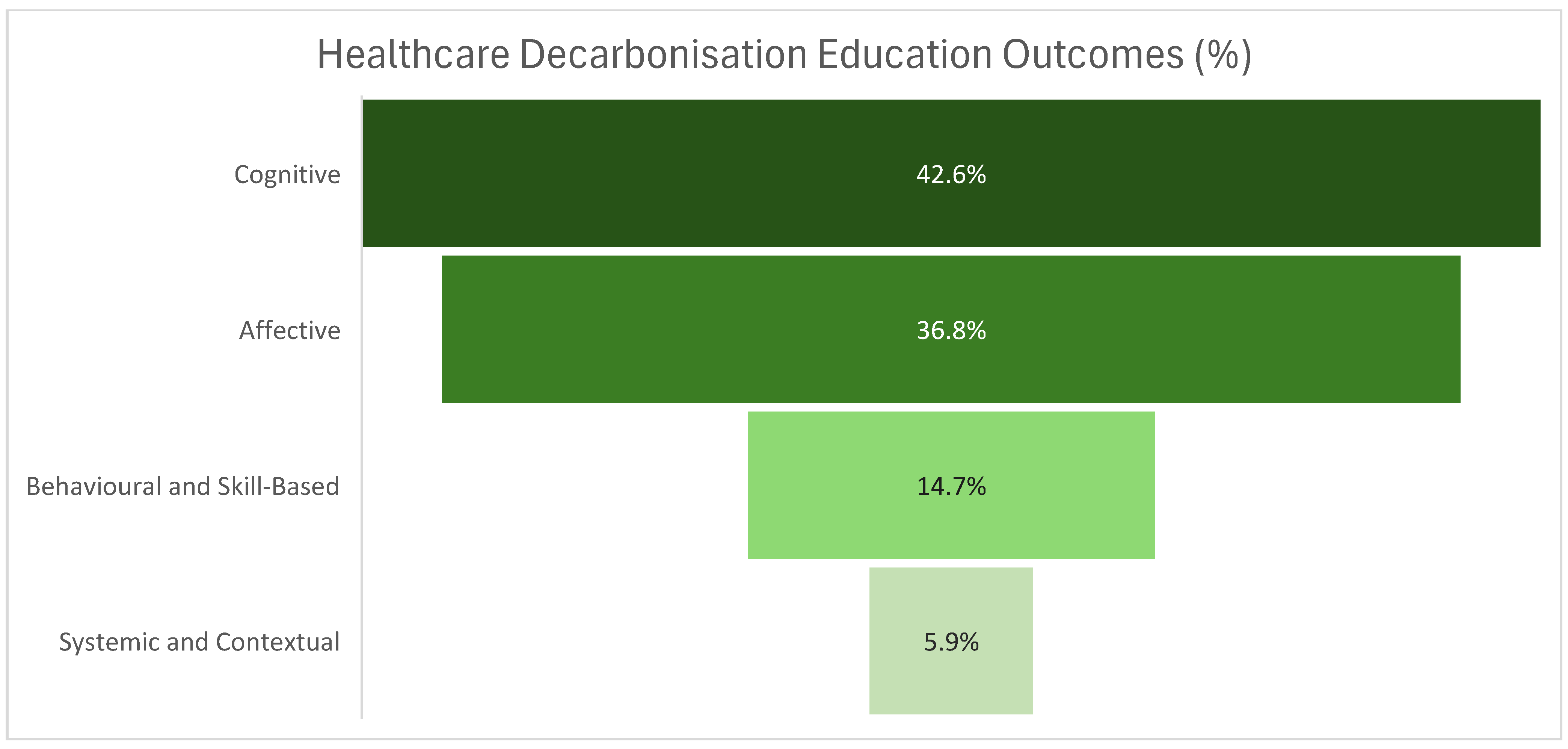

3.2. Study Results

3.2.1. Theme 1: Building a Decarbonisation Mindset

3.2.2. Theme 2: From Concern to Constructive Engagement

3.2.3. Theme 3: Translating Awareness into Decarbonisation Practices

3.2.4. Theme 4: Becoming Low-Carbon Change Agents

3.2.5. Theme 5: Barriers to Decarbonisation Action

4. Discussion

4.1. Relevance to Health Profession Education and Recommendations

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UN | United Nations |

| ATACH | Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate Change and Health |

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| GCCHE | Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis extension for ScRs |

| PCC | Population Concept Context |

| PEO | Population Exposure Outcome |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| ESE | Environmental Self-Efficacy |

| SBL | Scenario-Based Learning |

| AEBCD | Accelerated Experience-Based Co-Design |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health and Climate Change Global Survey Report 2021: Tracking Global Progress Toward Climate-Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Systems. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038509 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar]

- Karliner, J.; Slotterback, S.; Boyd, R.; Ashby, A.; Steele, K.; Wang, J. Health care’s climate footprint: The health sector contribution and opportunities for action. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa165.843. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, P.; Jaccard, I.; Weisz, U.; Weisz, H. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 064004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, M.; Napoli, C.; Green, C.; Kennard, H.; Lampard, P.; Scamman, D.; Walawender, M.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: The imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet 2023, 402, 2346–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, E.; Cohen Tanugi-Carresse, A. Supporting Decarbonization of Health Systems—A Review of International Policy and Practice on Health Care and Climate Change. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Or, Z.; Seppanen, A.-V. The role of the health sector in tackling climate change: A narrative review. Health Policy 2024, 143, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirow, J.; Venne, J.; Brand, A. Green health: How to decarbonise global healthcare systems. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, I.M.; Beagley, J.; Quintana, A.V. The COP26 health commitments: A springboard towards environmentally sustainable and climate-resilient health care systems? J. Clim. Change Health 2022, 6, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Care Without Harm (HCWH). Designing A Net Zero Roadmap for Healthcare: Technical Methodology and Guidance. 2022. Available online: https://noharm-europe.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/7186/2022-08-HCWH-Europe-Designing-a-net-zero-roadmap-for-healthcare-web.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Operational Framework for Building Climate Resilient and Low Carbon Health Systems. Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081888 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- National Health Service (NHS). England. Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service. Report. 2022, pp. 1–76. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/publication/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Braithwaite, J.; Smith, C.L.; Leask, E.; Wijekulasuriya, S.; Brooke-Cowden, K.; Fisher, G.; Patel, R.; Pagano, L.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Spanos, S.; et al. Strategies and tactics to reduce the impact of healthcare on climate change: Systematic review. BMJ 2024, 387, e081284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-Document A/42/427. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Mago, A.; Dhali, A.; Kumar, H.; Maity, R.; Kumar, B. Planetary health and its relevance in the modern era: A topical review. SAGE Open Med. 2024, 12, 20503121241254231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations (UN): New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Maibach, E.; Frumkin, H.; Ahdoot, S. Health professionals and the climate crisis: Trusted voices, essential roles. World Med. Health Policy 2021, 13, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, R.; Middleton, J.; Krafft, T.; Czabanowska, K. Climate action at public health schools in the European region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.T.; Pinho-Gomes, A.C.; Hamacher, N.; Nabbe, M.; Duggan, K.; Zjalic, D.; Magalhaes, D.; Campbell, H.; Cadeddu, C.; Demetriou, C.A.; et al. Climate and health capacity building for health professionals in Europe: A pilot course. Int. J. Public Health 2025, 70, 1608469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guidance for Climate Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities. 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/335909 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Zaleniene, I.; Pereira, P. Higher education for sustainability: A global perspective. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, C.; Campbell, H.; Depoux, A.; Finkel, M.; Gilden, R.; Hadley, K.; Haine, D.; Mantilla, G.; McDermott-Levy, R.; Potter, T.M.; et al. Core competencies to prepare health professionals to respond to the climate crisis. PLOS Clim. 2023, 4, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Abo-Khalil, A.G. Integrating sustainability into higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, G.; Collins, J.; Bedi, G.; Bonnamy, J.; Barbour, L.; Ilangakoon, C.; Wotherspoon, R.; Simmons, M.; Kim, M.; Schwerdtle, P.N. “I teach it because it is the biggest threat to health”: Integrating sustainable healthcare into health professions education. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Shantharam, L.; MacDonald, B.K. Sustainable healthcare in medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 689. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, M.; Gibbs, T. Addressing Code Red for humans and the planet. Med. Teach. 2022, 44, 462–465. [Google Scholar]

- Redvers, N.; Guzman, C.A.F.; Parkes, M.W. Towards an educational praxis for planetary health. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Moroney, T.; Bonnamy, J.; Cornish, J.; Moll, E.C.; Foster, A.; Lapkin, S.; Pich, J.; Richards, C.; Tutticci, N.; et al. Healthy planet, healthy people boardgame evaluation. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 152, 106753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenberg, K.; Apollonio, D.; MacDougall, C.; Brock, T. Sustainable pharmacy education. Innov. Pharm. 2017, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walpole, S.C.; Mortimer, F. Sustainable healthcare education in UK medical schools. Public Health 2017, 150, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazan, J.U.; Manabat, A.; Kavashev, Z.; Smagulova, M.; Colet, P.C.; Balay-odao, E.M.; Nurmagambetova, A.; Bolla, S.R.; Syzdykova, A.; Dauletkaliyeva, Z.; et al. Sustainability in education and healthcare field: An Integrative Review of Factors, Barriers, and the Path Forward for Informed Practices. Health Prof. Educ. 2024, 10, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, L.; Meznikova, K.; Crampton, P.; Johnson, T. Sustainable healthcare education: A systematic review. Med. Teach. 2022, 45, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.E.; Madden, D. Climate change and sustainability themes in health education. J. Clim. Change Health 2023, 9, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalapati, T.; Nick, S.E.; Chari, T.A.; George, I.A.; Hunter Aitchison, A.; MacEachern, M.P.; O’Sullivan, A.N.; Taber, K.A.; Muzyk, A. Interprofessional climate change curriculum. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, P.R.; Mathur, K.; Miab, R.K.; Cohen, N.; Henriques-Thompson, K. Environmental sustainability, healthcare workers and healthcare students: A literature review of attitudes and learning approaches. Health Prof. Educ. 2024, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, S.; Breakey, S.; Fanuele, J.R.; Kelly, D.E.; Eddy, E.Z.; Tarbet, A.; Nicholas, P.K.; Viamonte Ros, A.M. Roles of Health Professionals in Addressing Health Consequences of Climate Change in Interprofessional Education: A Scoping Review. J. Clim. Change 2022, 5, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Berta, W.; Shea, C.; Miller, F. Environmental competencies for healthcare educators and trainees: A scoping review. Health Educ. J. 2020, 79, 327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.-S.; Jahanshalou, F.; Akbarzadeh, M.A.; Zarei, M.; Vaez-Gharmaleki, Y. Formulating research questions for evidence-based studies. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). JBI Template Source of Evidence Details, Characteristics and Results Extraction Instrument (Appendix 10.1). 2024. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355863340 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for extraction, analysis and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Davey, L.; Jenkinson, E. Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis. In Supporting Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy; Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Elhosy, H.S.; Aref, S.R.; Rizk, M.H. Evaluation of Planetary Health and Sustainable Healthcare Online Course for Undergraduate Medical Students: A Quasi-experimental Study. Med. Sci. Educ. 2025, 35, 2501–2513. [Google Scholar]

- Moro, C.; Phelps, C.; Veer, V.; McLean, M. Successfully integrating sustainability into medical science education with mixed-method iterative approaches. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2025, 49, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merduaty, R.C.; Jacinta, H.A.; Saptura, R.; Susanti, S.S.; Wanda, D.; Lokmic-Tomkins, Z. Integrating climate change education in preregistration nursing degree in Indonesia: A case study. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 155, 106878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sheehy, L.; Frotjold, A.; Power, T.; Saravanos, G. Sustainability in undergraduate nursing clinical simulation: A mixed methods study exploring attitudes, knowledge and practices. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 153, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaşıkçı, M.; Bağcı, Y.; Yıldırım, Z.; Nacak, U.A. Carbon footprint awareness of nursing students: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlaslan, N.; Şahin Orak, N. Sustainable healthcare education using cooperative simulation in developing nursing students’ knowledge, attitude and skills: A randomized controlled study. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 151, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweida, R.S.; O’Connell, M.A.; Zoromba, M.; Mahmoud, M.F.; Altheeb, M.K.; Selim, A.; Atta, M.H.R. Video-based climate change program boosts eco-cognizance, emotional response and self-efficacy in rural nursing students: Randomised controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 8371–8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çolak, M.; Dogan, R.; Dogan, S. Effect of Climate Change and Health Course on Global Warming Knowledge and Attitudes, Environmental Literacy, and Eco-Anxiety Level of Nursing Students. Public Health Nurs. 2025, 42, 1315–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Baird, H.M.; Field, J.; Martin, N. Longitudinal integration of environmental sustainability in the dental curriculum. J. Dent. 2025, 156, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Álvarez-García, C.; Montoro Ramirez, E.M.; López-Franco, M.D.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López Medina, I.M. Sustainability education in nursing degree for climate-smart healthcare: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Israel, A.; Nusselder, A.; Mattijsen, J.C.; Chen, F.; Erasmus, V.; van Beeck, E.; Otto, S. Evaluation of medical students’ knowledge and attitudes towards climate change and health following a novel serious game. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T.; Stark, P.; Craig, S.; McMullan, J.; Anderson, G.; Hughes, C.; Gormley, K.; Killough, J.; McLaughlin-Borlace, N.; Steele, L.; et al. Co-design and evaluation of an audio podcast about sustainable development goals for undergraduate nursing and midwifery students. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1253. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, V.; Grossi, E.; Levin-Carrion, Y.; Sahu, N.; DallaPiazza, M. Interactive mapping and case seminar introducing medical students to climate change, environmental justice and health. MedEdPORTAL 2024, 20, 11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, M.C.; Malits, J.R.; Baker, N.; Shirley, H.; Grobman, B.; Callison, W.E.; Pelletier, S.; Nadeau, K.; Jones, D.S.; Basu, G. Implementation and initial evaluation of a longitudinal, integrated curricular theme and competency framework. PLoS Clim. 2024, 3, e0000412. [Google Scholar]

- Coronel-Zubiate, F.T.; Farje-Gallardo, C.A.; Rojas de la Puente, E.E. Environmental impact of waste in dental care: Educational strategies to promote environmental sustainability. Environ. Technol. Resour. Proc. Int. Sci. Pract. Conf. 2024, 11, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, B.; Hawkins, J. Climate and Health: Impact of Climate Education on Nursing Student Knowledge and Intent to Act. Nurse Educ. 2024, 49, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, D.; Holtz, S.; Gerber, M.; Amberger, O.; Schütze, D.; Müller, B.; Wunder, A.; Fast, M. From niche topic to inclusion in the curriculum—Design and evaluation of the elective course “climate change and health”. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2023, 40, Doc31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.; Kühl, M.; Kühl, S.J. Changes in student environmental knowledge and awareness due to mandatory elective. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2023, 40, Doc32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gundacker, C.; Himmelbauer, M. Impact of climate change on the medical profession: A newly implemented course. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2023, 40, Doc30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, O.D.; Londono, C.A.; Prince, N.; Iny, E.; Warnock, T.; Cropper, K.; Girgis, S.; Walker, C. The Climate Wise slides: An evaluation of planetary health lecture slides for medical education. Med. Teach. 2023, 45, 1346–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, H.H.; Tucker, M.; Couig, M.P.; Svihla, V. Interprofessional course on climate change and public health preparedness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimings, C.; Sisson, E.; Larson, C.; Bowles, D.; Hussain, R. Preparing future doctors in a destabilised world. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Medina, I.M.; Álvarez-García, C.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Sanz-Martos, S.; Álvarez-Nieto, C. Perceptions and concerns about sustainable healthcare of trained nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 65, 103489. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Álvarez-García, C.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López-Medina, I.M. Scenario-based learning and augmented reality for nursing students. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clery, P.; d’Arch Smith, S.; Marsden, O.; Leedham-Green, K. Sustainability in quality improvement (SusQI): A case-study in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, O.; Clery, P.; d’Arch Smith, S.; Leedham-Green, K. Sustainability in Quality Improvement (SusQI): Challenges and strategies for translating undergraduate learning into clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.; Goshua, A.; Pokrajac, N.; Erny, B.; Auerbach, P.; Nadeau, K.; Gisondi, M.A. Teaching medical students about the impacts of climate change on human health. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 100020. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.; Clarke, D.; Grose, J.; Warwick, P. Sustainability education in nursing: A cohort study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 747–760. [Google Scholar]

- Aronsson, J.; Clarke, D.; Grose, J.; Richardson, J. Student nurses exposed to sustainability education. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J.; Grose, J.; Bradbury, M.; Kelsey, J. Scenario-based learning for sustainability in nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 54, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Grose, J.; Richardson, J. Sustainability and health scenario challenge. Nurs. Health Sci. 2016, 18, 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.; Grose, J.; O’Connor, A.; Bradbury, M.; Kelsey, J.; Doman, M. Nursing students’ attitudes toward sustainability. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, L.; Filmalter, C.; Maree, C. Teaching, learning and assessment of the affective domain of undergraduate students: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2025, 86, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, V.; Barna, S.; Gupta, D.; Mortimer, F. Teaching skills for sustainable health care. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e64–e67. [Google Scholar]

- Er, S.; Murat, M.; Ata, E.E.; Köse, S.; Buzlu, S. Nursing students’ mental health and eco-anxiety. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 33, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Eren, D.C.; Yildiz, M.K. Is climate change awareness a predictor of anxiety among nursing students?: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 143, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Safer, D.L.; Cosentino, M.; Cooper, R.; van Susteren, L.; Coren, E.; Nosek, G.; Lertzman, R.; Sutton, S. Coping with eco-anxiety: An interdisciplinary perspective for collective learning and strategic communication. J. Clim. Change Health 2023, 9, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhalalati, B.; Elshami, S.; Eljaam, M.; Hussain, F.N.; Bishawi, A.H. Social theories of learning in health professions education. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 912751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsburgh, J.; Ippolito, K. Learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Arlinghaus, K.R.; Johnston, C.A. Advocating for behaviour change with education. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 12, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Navarro, C.; Armstrong, R.; Charnetski, M.; Freeman, K.J.; Koh, S.; Reedy, G.; Smitten, J.; Ingrassia, P.L.; Matos, F.M.; Issenberg, B. Global consensus statement on simulation-based practice. Adv. Simul. 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Okatta, A.U.; Amaechi, E.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Ezeh, C.P.; Elendu, I.D. Impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.; Canham, R.; Hughes, K.; Tallentire, V.R. Simulation-based education and sustainability: Creating a bridge to action. Adv. Simul. 2025, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, S.; Hughes, R.; Dhugga, A.; Oshodi, K.; Palta, C.; Jankowska, M.; Tso, S.; SWFT Medical Education Sustainability Group. A novel approach for quantifying the carbon footprint of different medical education teaching modalities in an NHS hospital trust. Clin. Teach. 2025, 22, e70179. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, A.; Rowe, D.; Brundiers, K.; Brock, A. What motivates students to be sustainability change agents in the face of adversity? Sustain. Clim. Change 2021, 14, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Homeyer, S.; Hoffmann, W.; Hingst, P.; Oppermann, R.F.; Dreier-Wolfgramm, A. Effects of interprofessional education for medical and nursing students: Enablers, barriers and expectations for optimizing future interprofessional collaboration: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, D.A.; Penner, J.L.; Halas, G.; Philip, M.T.; Cooke, C.A. Experiential learning in interprofessional education: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beevers, S.; Assareh, N.; Beddows, A.; Stewart, G.; Holland, M.; Fecht, D.; Liu, Y.; Goodman, A.; Walton, H.; Brand, C.; et al. Climate change policies reduce air pollution and increase physical activity: Benefits, costs, inequalities, and indoor exposures. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walton, H.; Dajnak, D.; Holland, M.; Evangelopoulos, D.; Wood, D.; Brand, C.; Assareh, N.; Stewart, G.; Beddows, A.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Health and associated economic benefits of reduced air pollution and increased physical activity from climate change policies in the UK. Environ. Int. 2025, 196, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutet, L.; Bernard, P.; Green, R.; Milner, J.; Haines, A.; Slama, R.; Temime, L.; Jean, K. The public health co-benefits of strategies consistent with net-zero emissions: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e145–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health Co-Benefits of Climate Action. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/climate-change-and-health/capacity-building/toolkit-on-climate-change-and-health/cobenefits (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Aboueid, S.; Beyene, M.; Nur, T. Barriers and enablers to implementing environmentally sustainable practices in healthcare: A scoping review and roadmap. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2023, 36, 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, G.F.; Luo, Y.; Huang, M.Q.; Geng, F. The impact of career calling on learning engagement: The role of professional identity and need for achievement in medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J. Effectiveness of education for sustainable development: A longitudinal study. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Study Characteristics | Empirical studies Literature reviews (to search reference lists) English language | Non-empirical studies Studies not in the English language |

| Participants | More than 50% of participants are pre-registration health profession students (nursing, medicine, pharmacy, dentistry) Aged 18 years or older | Less than 50% of participants are pre-registration health profession students (nursing, medicine, pharmacy, dentistry) Participants under 18 years of age Post-graduate students Registered health professionals Non-health profession students |

| Concept | Educational resources related to healthcare decarbonisation Studies reporting student outcomes and experiences Education on climate change, sustainability, or planetary health (if decarbonisation is discussed) | Educational resources with no content relating to decarbonisation Studies without student-specific outcomes or experiences Education on climate change, sustainability, or planetary health (if no decarbonisation is discussed) Studies with no educational intervention |

| Context | All types of educational resources Higher education setting Clinical teaching areas (as long as population is correct) All geographical locations | Studies conducted outside of educational or clinical training settings |

| Population | “Nursing Students” OR “Medical Students” OR “Pharmacy Students” OR “Dental Students” OR “Health Professions Students” OR “Nursing Education” OR “Medical Education” OR “Allied Health Education” OR “Health Education” |

| Exposure | Decarboni?ation OR Sustainability OR “Climate change” OR “Planetary health” OR “Sustainable Development Goals” OR SDGs OR “Environmentally Friendly” OR “Green Skills” |

| Outcome | Education OR Curriculum OR “E-learning” OR Training OR Pedagogy OR “Instructional Design” OR Learning OR “Learning Interventions” OR “Blended Learning” OR “Learning Management System” OR “Virtual Classroom” OR “Flipped learning” OR “Active Learning” |

| Citation | Country of Origin | Aim | Population | Concept | Context | Study Design | Data Collection | Data Analysis | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e.g., Smith, J., et al. (2025) | The country or region where the study was conducted | The main objective or research question of the study | Details of participants, sample size, age, or other relevant demographics | The main topic or focus of the study | Setting or environment of the study | The methodological approach used | Methods used to gather data | Techniques or tools used to analyse the data | Main results relevant to the review |

| Theme | Key Findings | Behavioural/Practice Outcomes | Pedagogical/Contextual Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Building a Decarbonisation Mindset | Improved knowledge, awareness, and understanding of healthcare decarbonisation; recognition of climate–health-professional practice link; reframing decarbonisation as professional responsibility | Identification of carbon-intensive practices (anaesthetic gases, PPE, procurement) Self-reported awareness of system-level drivers | Scenario-based learning Augmented reality Planetary health modules Simulation Quality improvement projects Practical relevance enhances intrinsic motivation |

| 2. From Concern to Constructive Engagement | Positive attitudes toward climate mitigation and sustainability; eco-anxiety transformed into constructive engagement; moral responsibility and professional accountability | Increased willingness to engage in sustainability-related actions Emotional resilience supports action | Solution-focused framing fosters optimism and agency Immersive approaches can heighten distress but also urgency Structured workshops |

| 3. Translating Awareness into Decarbonisation Practices | Knowledge and attitudes frequently translated into professional action; spillover to personal behaviours | Clinical actions: optimise investigations, appropriate PPE use, low-carbon inhalers, advocacy for sustainable clinical practices Leadership roles in peer engagement | Context-specific interventions Simulations Waste management training Advocacy workshops enhance actionable competence |

| 4. Becoming Low-Carbon Change Agents | Professional identity shaped around sustainability; recognition of ethical duty to reduce healthcare’s environmental impact | Active engagement as change agents Interprofessional collaboration Peer mentoring Advocacy Reflective and applied decision making | Collaborative and experiential learning Scenario-based learning Serious games Podcasts Augmented reality Structured debriefs |

| 5. Barriers to Decarbonisation Action | Hierarchical, structural, and emotional barriers limit translation of learning; uncertainty about advocacy and operationalisation | Reduced opportunity for practice-level change due to institutional constraints, time pressures, and lack of role models | Highlights need for multi-level support: safe learning environments, applied training, advocacy pathways, and alignment of institutional policies with sustainability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

McLaughlin-Borlace, N.; Mitchell, G.; Flood, N.; Steele, L.; Anderson, T.; Al Halaiqa, F.; Hammoudi Halat, D.; Binti Ahmad, N.; Levett-Jones, T.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; et al. Healthcare Decarbonisation Education for Health Profession Students: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021068

McLaughlin-Borlace N, Mitchell G, Flood N, Steele L, Anderson T, Al Halaiqa F, Hammoudi Halat D, Binti Ahmad N, Levett-Jones T, Sánchez-Martín J, et al. Healthcare Decarbonisation Education for Health Profession Students: A Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcLaughlin-Borlace, Nuala, Gary Mitchell, Nuala Flood, Laura Steele, Tara Anderson, Fadwa Al Halaiqa, Dalal Hammoudi Halat, Norfadzilah Binti Ahmad, Tracy Levett-Jones, Jesús Sánchez-Martín, and et al. 2026. "Healthcare Decarbonisation Education for Health Profession Students: A Scoping Review" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021068

APA StyleMcLaughlin-Borlace, N., Mitchell, G., Flood, N., Steele, L., Anderson, T., Al Halaiqa, F., Hammoudi Halat, D., Binti Ahmad, N., Levett-Jones, T., Sánchez-Martín, J., & Craig, S. (2026). Healthcare Decarbonisation Education for Health Profession Students: A Scoping Review. Sustainability, 18(2), 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021068