Energy Justice, Critical Minerals, and the Geopolitical Metabolism of the Global Energy Transition: Insights from Copper Extraction in Chile and Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Background

2.1. The Changing Energy Transition Geopolitics

2.2. Calls for an Ecological Geopolitics

2.3. Geopolitical Metabolism

2.4. Energy Justice Lenses

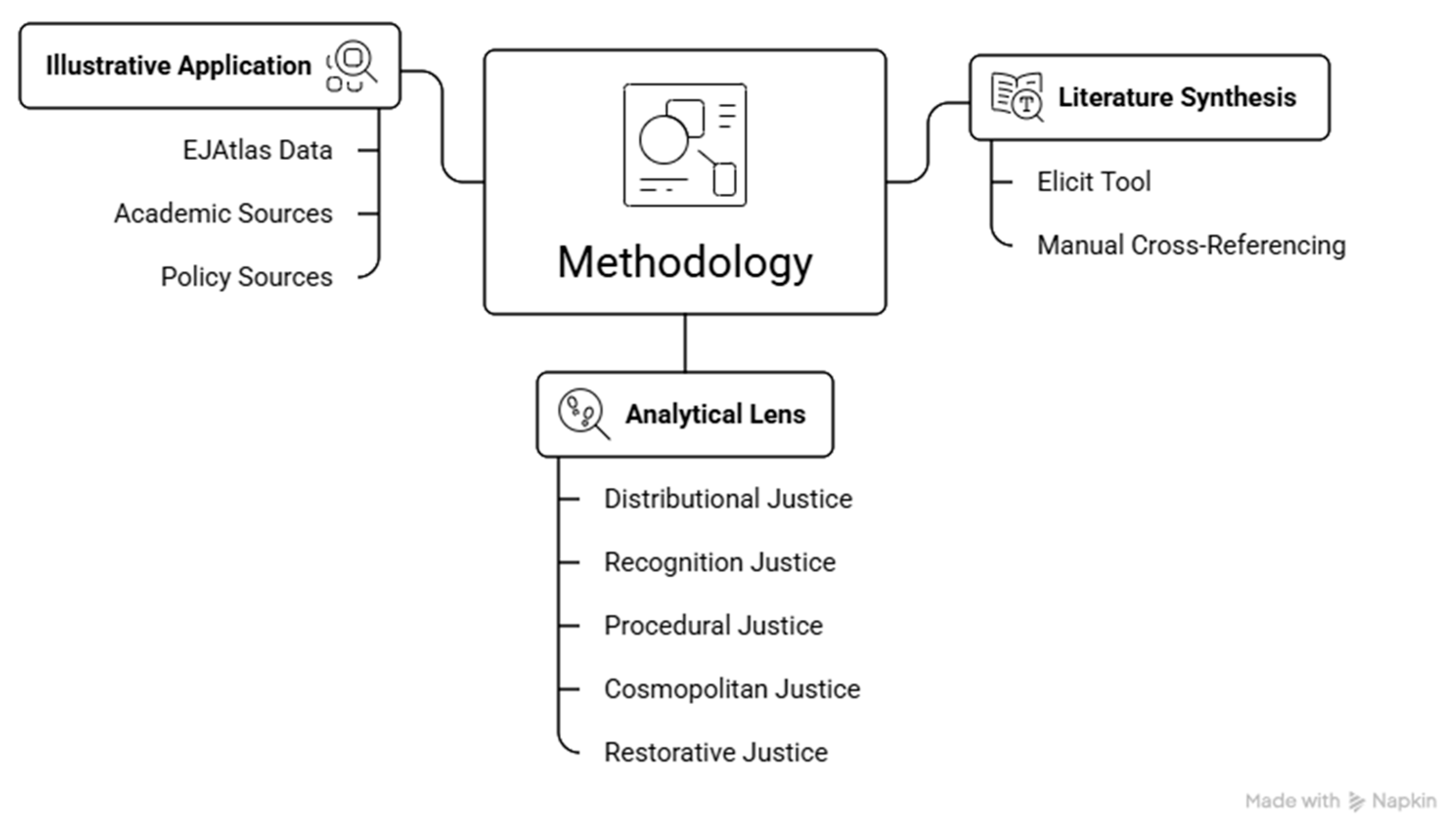

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Orienting the Corpus

3.2. Analytical Lens

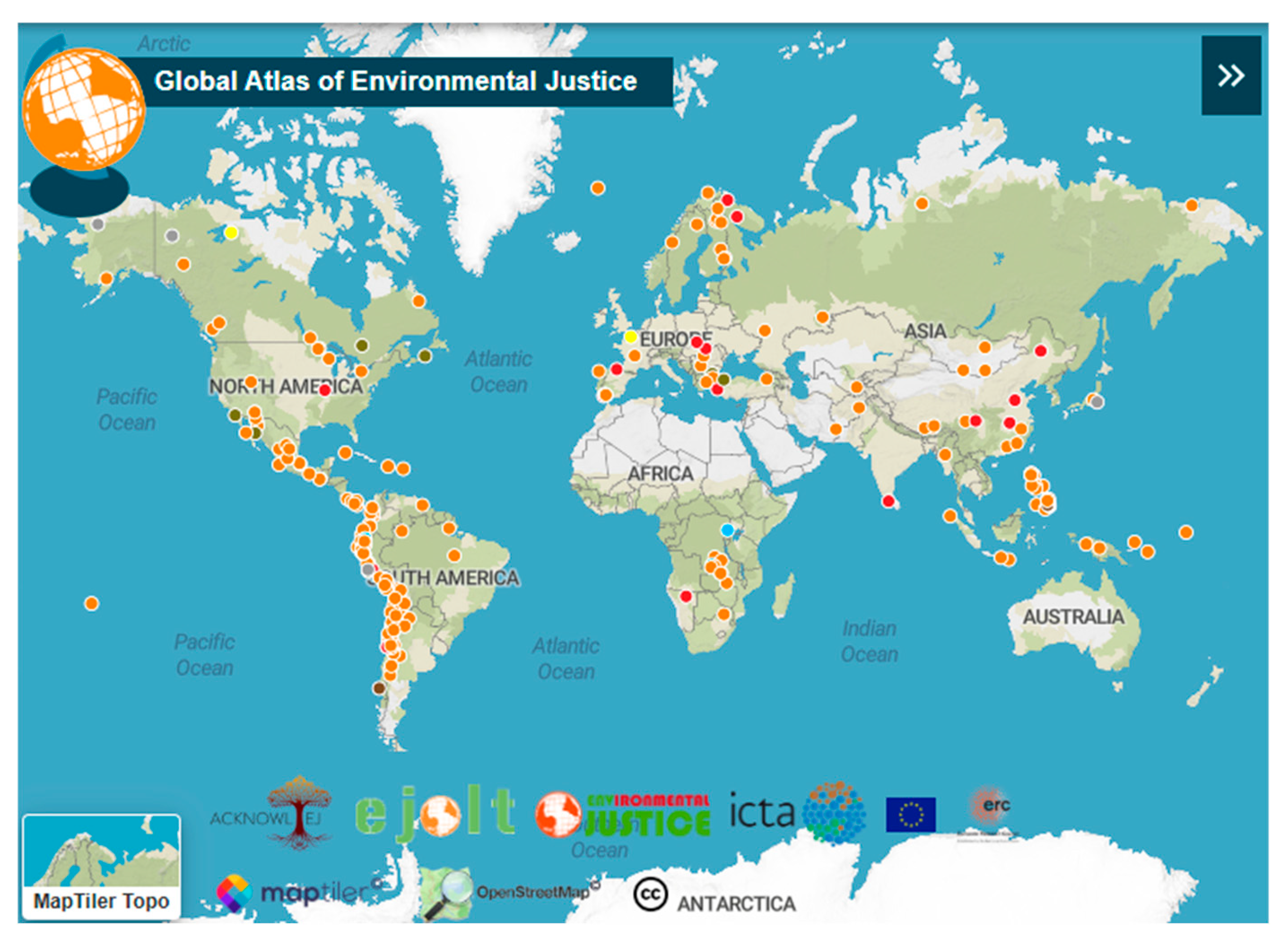

3.3. A Quick Illustrative Application

4. Results of the Guided Literature Synthesis and Illustrative Case

4.1. Integrating Energy Justice, Green Extractivism, and Decolonialisation

4.2. Exploring How Geopolitical Metabolism and Peripheral Territory Dynamics Interact

4.3. Synthesis: Enhancing Energy Justice Tenets

4.3.1. Transnational Distributive Tenet Enhancing a Classical View of the Distributive Tenet

4.3.2. Plural Recognition Tenet Enhancing a Classical View of the Recognition Tenet

4.3.3. Confronting Power Asymmetries Through Procedural Justice

4.3.4. Cosmopolitan and Restorative Justice

4.4. A Sketch of a Brief Illustrative Application

4.4.1. The Copper Case

4.4.2. The Chilean and Peruvian Copper Cases Under the Classical Three Tenets

4.4.3. The Chilean and Peruvian Copper Cases Under the Reframed Tenets

“They are autonomous in their organisation, in communal work, and in the use and free disposal of their lands, as well as in economic and administrative matters, within the framework established by law. Ownership of their lands is imprescriptible, except in the case of abandonment provided for in the previous article. The state respects the cultural identity of the Peasant and Native Communities.”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| EJ | Energy justice |

| ET | Energy transition |

| EJAtlas | Atlas of Environmental Justice |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| PESET | Political Ecology Framework for Sustainable Energy Transition |

| REDD+ | Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation |

Appendix A

| Issue | Elicit’s Instruction |

|---|---|

| Theoretical framework | Identify and extract the primary theoretical frameworks used in the study. Look for explicit mentions of: EJ framework, green extractivism, geopolitical metabolism, coloniality/postcolonial perspectives, Indigenous perspectives on ET. |

| Geographical focus | Extract detailed information about the geographical context of the study: specific regions or territories studied, relationship between territories (e.g., centre-periphery dynamics), Indigenous territories or communities involved, geopolitical relationships highlighted. Provide precise geographical details, including: country/countries, specific regions or territories, and type of territory (e.g., Indigenous land, extractive zone). |

| Power redistribution and social burden analysis | Identify and extract information about the social, ecological, and geopolitical burdens redistributed through ET, as well as the power dynamics between different actors (e.g., multinational corporations, Indigenous communities, national governments), the mechanisms of burden externalisation, and patterns of dispossession or marginalisation. Look for: explicit discussions of burden redistribution, comparative analysis of different actors’ positions, and mechanisms of power reproduction. Extract specific examples or case studies that illustrate these dynamics. |

| Indigenous perspectives | Extract information about: Indigenous community responses to ET projects, self-determination and autonomy claims, cultural and territorial implications, resistance strategies. Focus on: direct quotes from Indigenous leaders/authorities, specific demands or proposals, challenges to existing ET models. |

| Methodological approach and data sources | Identify and extract: research methodology (qualitative, theoretical analysis, etc.), primary data sources, analytical techniques, theoretical or empirical approach, and provide details such as the type of analysis (e.g., discourse analysis, policy analysis), data collection methods, and specific analytical frameworks used. |

References

- Poque González, A.B. Por que aprofundar na relação entre energia, ambiente e sociedade-Algumas reflexões desde a América Latina. Gavagai 2024, 10, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Gregg, J.W.; Rockström, J.; Newsome, T.M.; Law, B.E.; Marques, L.; Lenton, T.M.; Xu, C.; Huq, S.; et al. The 2023 State of the Climate Report: Entering Uncharted Territory. BioScience 2023, 73, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, E.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Zscheischler, J. A Year above 1.5 °C Signals That Earth Is Most Probably within the 20-Year Period That Will Reach the Paris Agreement Limit. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2025, 15, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Mann, M.E.; Rockström, J.; Gregg, J.W.; Xu, C.; Wunderling, N.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Schaeffer, R.; Broadgate, W.J.; et al. The 2025 State of the Climate Report: A Planet on the Brink. BioScience 2025, 75, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Kumar, A. Energy Geographies in/of the Anthropocene: Where Now? Geogr. Compass 2022, 16, e12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Bringel, B.; Manahan, M.A. (Eds.) Más Allá del Colonialismo Verde: Justicia Global y Geopolítica de Las Transiciones Ecosociales, 1st ed.; CLACSO: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023; ISBN 978-987-813-605-9. [Google Scholar]

- Voskoboynik, D.M.; Andreucci, D. Greening Extractivism: Environmental Discourses and Resource Governance in the ‘Lithium Triangle’. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2022, 5, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kramarz, T.; Johnson, C. Governance Gaps and Accountability Traps in Renewables Extractivism. Environ. Policy Gov. 2024, 34, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainton, N.; Kemp, D.; Lèbre, E.; Owen, J.R.; Marston, G. The Energy-extractives Nexus and the Just Transition. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poque González, A.B. Claves para entender el rol geopolítico de América Latina en la transición energética global. Una aproximación desde la teoría de la dependencia. In Prefigurar el Futuro. Dinámicas Extractivas y Energéticas en Clave Latinoamericana; Miradas Latinoamericanas; CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2025; pp. 137–164. ISBN 978-631-308-030-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cederlöf, G. Out of Steam: Energy, Materiality, and Political Ecology. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, A. The Geopolitics of the Green Transition and Critical Strategic Minerals. Int. J. 2025, 80, 217–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantzakos, S. The Race for Critical Minerals in an Era of Geopolitical Realignments. Int. Spect. 2020, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, E.; Le Billon, P. The ‘Green War’: Geopolitical Metabolism and Green Extractivisms. Geopolitics 2025, 30, 760–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- World Economic Forum. Making Mining Safe and Fair: Artisanal Cobalt Extraction in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Making_Mining_Safe_2020.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Poque González, A.B. Conflicts Linked to Critical Minerals and Renewables in South America—The Hydropower and Copper Cases through the Energy Justice Lens. In Energy Justice in Latin America: Reflections, Lessons and Critiques; Routledge & CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-1-032-79532-4. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.B.P.; Macia, Y.M.; Ferreira, L.d.C.; Valdes, J. Socioecological Controversies from Chilean and Brazilian Sustainable Energy Transitions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Directory Geopolitical Ecology → Term. Climate. Sustainability-Directory 2025. Available online: https://climate.sustainability-directory.com/term/geopolitical-ecology/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kurniawan, N.I.; Winanti, P.S.; Cahyati, D.D. Recarbonization Through Decarbonization: Nickel Extraction and the Deepening of Fossil Fuel Dependence in Indonesia. Glob. Environ. Politics 2025, 25, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yergin, D. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power; Free Press trade pbk. ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4391-1012-6. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, M.; Overland, I.; Sandalow, D. The Geopolitics of Renewable Energy. SSRN J. 2017, RWP17-027, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, D.; Bazilian, M.; Overland, I.; Westphal, K. The Geopolitics of Renewables: New Board, New Game. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Geopolitics of the Energy Transition: Critical Materials. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Digital-Report/Geopolitics-of-the-Energy-Transition-Critical-Materials (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Kuzemko, C.; Blondeel, M.; Bradshaw, M.; Bridge, G.; Faigen, E.; Fletcher, L. Rethinking Energy Geopolitics: Towards a Geopolitical Economy of Global Energy Transformation. Geopolitics 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, D. Chapter 1: Introduction: The Geopolitics of the Energy Transition. In Handbook on the Geopolitics of the Energy Transition; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-1-80037-043-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vivoda, V.; Matthews, R.; McGregor, N. A Critical Minerals Perspective on the Emergence of Geopolitical Trade Blocs. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poque González, A.B. New Commodity Frontiers: Chile and Indonesia in the Geopolitics of Critical Minerals. 2025. Available online: https://www.e-ir.info/2025/11/22/new-commodity-frontiers-chile-and-indonesia-in-the-geopolitics-of-critical-minerals/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- O’Sullivan, K.; Golubchikov, O.; Mehmood, A. Uneven Energy Transitions: Understanding Continued Energy Peripheralization in Rural Communities. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graddy-Lovelace, G.; Ranganathan, M. Geopolitical Ecology for Our Times. Political Geogr. 2024, 112, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Qian, X. Geopolitics of the Energy Transition. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Lear, S. Environmental Geopolitics: An Introduction to Questions and Research Approaches. In A Research Agenda for Environmental Geopolitics; O’Lear, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78897-124-9. [Google Scholar]

- Leff, E. Ecologia Política: Uma Perspectiva Latino-Americana. Desenvolv. Meio Ambiente. 2013, 35, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, O.; Bigger, P.; Neimark, B.; Kennelly, C. Hidden Carbon Costs of the “Everywhere War”: Logistics, Geopolitical Ecology, and the Carbon Boot-Print of the US Military. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2020, 45, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baasch, S. Towards an Integrative Understanding of Multiple Energy Justices. Geogr. Helv. 2023, 78, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Montero, A.; Jenkins, K.E.H. Whole-Systems Energy Justice. In Handbook on Energy Justice; Bouzarovski, S., Fuller, S., Reames, T., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-1-83910-295-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.A.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H. Energy Justice: A Whole Systems Approach. Queen’s Political Rev. 2014, 2, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Burke, M.; Baker, L.; Kotikalapudi, C.K.; Wlokas, H. New Frontiers and Conceptual Frameworks for Energy Justice. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Energy Justice: Conceptual Insights and Practical Applications. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffron, R.J. The Role of Justice in Developing Critical Minerals. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey-Barnacle, M.; Robison, R.; Foulds, C. Energy Justice in the Developing World: A Review of Theoretical Frameworks, Key Research Themes and Policy Implications. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 55, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrall-Wolf, I.; Gill-Wiehl, A.; Kammen, D.M. A Bibliometric Review of Energy Justice Literature. Front. Sustain. Energy Policy 2023, 2, 1175736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.; Rodríguez, F. Rights of Nature and World Order: Reimagining Socioecological Futures. Glob. Environ. Politics 2025, 25, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elicit. Available online: https://elicit.com (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Bernard, N.; Sagawa, Y., Jr.; Bier, N.; Lihoreau, T.; Pazart, L.; Tannou, T. Using Artificial Intelligence for Systematic Review: The Example of Elicit. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2025, 25, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podobińska-Staniec, M.; Wiktor-Sułkowska, A.; Kustra, A.; Lorenc-Szot, S. Copper as a Critical Resource in the Energy Transition. Energies 2025, 18, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poque González, A.B. Who Pays the Price? -Socioecological Controversies Regarding the Energy Transition in South America. SustDeb 2022, 13, 72–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; Del Bene, D.; Martinez-Alier, J. Mapping the frontiers and front lines of global environmental justice: The EJAtlas. J. Political Ecol. 2015, 22, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alier, J. Mapping Ecological Distribution Conflicts: The EJAtlas. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llavero-Pasquina, M. Driving Ecologically Unequal Exchange: A Global Analysis of Multinational Corporations’ Role in Environmental Conflicts. Glob. Environ. Change 2025, 92, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canelas, J.; Carvalho, A. The Dark Side of the Energy Transition: Extractivist Violence, Energy (in)Justice and Lithium Mining in Portugal. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 100, 103096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, D.; Bloomer, J.; Morrissey, J. Where the Power Lies: Developing a Political Ecology Framework for Just Energy Transition. Geogr. Compass 2023, 17, e12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.; Davies, M.; Bauwens, T.; Späth, P.; Hajer, M.A.; Arifi, B.; Bazaz, A.; Swilling, M. Working to Align Energy Transitions and Social Equity: An Integrative Framework Linking Institutional Work, Imaginaries and Energy Justice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornel, C. Decolonizing Energy Justice from the Ground up: Political Ecology, Ontology, and Energy Landscapes. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 47, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Tzompa, S.M.; Casimero, I.; Apagüeño, M.G. When the Past Meets the Future: Latin American Indigenous Futures, Transitional Justice and Global Energy Governance. Futures 2024, 163, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, A. Aesthetics of Green Dispossession: From Coal to Wind Extraction in La Guajira, Colombia. J. Political Ecol. 2023, 30, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Contreras, J.; Matarán Ruiz, A.; Campos-Celador, A.; Fjellheim, E.M. Energy Colonialism: A Category to Analyse the Corporate Energy Transition in the Global South and North. Land 2023, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnakar, P.; Singh, M.K. Local Governance in Just Energy Transition: Towards a Community-Centric Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreucci, D.; García López, G.; Radhuber, I.M.; Conde, M.; Voskoboynik, D.M.; Farrugia, J.D.; Zografos, C. The Coloniality of Green Extractivism: Unearthing Decarbonisation by Dispossession through the Case of Nickel. Political Geogr. 2023, 107, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, F.M. Green Colonialism in Latin America? Towards a New Research Agenda for the Global Energy Transition. Eur. Rev. Lat. Am. Caribb. Stud. 2022, 144, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OEC. Available online: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/copper-ore/reporter/chl (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Dunlap, X. This System Is Killing Us: Land Grabbing, the Green Economy and Ecological Conflict; first published; Pluto Press: London, UK; Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-0-7453-4883-4. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. “This Lofty Mountain of Silver Could Conquer the Whole World”: Potosí and the Political Ecology of Underdevelopment, 1545–1800. J. Philos. Econ. 2010, 4, 58–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, E. Mineral Extraction on Indigenous Land: Employing a Relational Approach to Navigate the Convergence of Indigenous and Other Ontologies and Practices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 125, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collao Quevedo, M.F.C. Extractivist Ontologies: Lithium Mining and Anthropocene Imaginaries in Chile’s Atacama Desert. Intertexts 2023, 27, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BCN. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Constitución de Perú. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/procesoconstituyente/comparadordeconstituciones/constitucion/per (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Palacio de la Moneda. Autoridades Detallan Reforma Constitucional para el Reconocimiento de los Pueblos Indígenas Anunciada por el Presidente Gabriel Boric-Ministerio del Interior. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.cl/noticias/2025/06/19/autoridades-detallan-reforma-constitucional-para-el-reconocimiento-de-los-pueblos-indigenas-anunciada-por-el-presidente-gabriel-boric/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Roberts, J.T.; Parks, B.C. Ecologically Unequal Exchange, Ecological Debt, and Climate Justice: The History and Implications of Three Related Ideas for a New Social Movement. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2009, 50, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, K.S. The Thermodynamics of Unequal Exchange: Energy Use, CO2 Emissions, and GDP in the World-System, 1975—2005. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2009, 50, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azamar-Alonso, A.; Carrillo-González, G. Extractivismo y deuda ecológica en América Latina. LuAZ 2017, 45, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C.; Atencio, E. Past, Present, and Future of Copper Mine Tailings Governance in Chile (1905–2022): A Review in One of the Leading Mining Countries in the World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SERNAGEOMIN. Cierre Faenas Mineras. Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería; SERNAGEOMIN: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Estado Peruano. Ley y Reglamento que Regula el Cierre de Minas. Ed. 2025. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minem/informes-publicaciones/4156124-ley-y-reglamento-que-regula-el-cierre-de-minas-ed-2025 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

| Criteria | Definition |

|---|---|

| Does this research treat EJ as a central or major topic (rather than as a minor or tangential consideration)? |

| Does this study focus on renewable energy development, mining for ET materials, or energy infrastructure projects related to ET? |

| Does this research include consideration of peripheral territories or impacts (i.e., is it NOT limited exclusively to core/developed countries without any consideration of peripheral impacts)? |

| Does this study analyse social, ecological, or geopolitical impacts of ET (rather than focusing solely on technical or economic aspects)? |

| Does this study examine EJ in peripheral territories (e.g., Global South countries, marginalised regions, or areas experiencing economic/geographic peripheralisation)? |

| Is this a peer-reviewed academic article, book, or book chapter (not a conference abstract, editorial, or opinion piece)? |

| Does this research incorporate at least two of the three key concepts: EJ, geopolitical metabolism, and/or green extractivism? |

| Article | Theoretical Framework | Main Argument |

|---|---|---|

| EJ, green extractivism | Argue that the ET reproduces extractivist logics by intensifying resource exploitation and socioenvironmental inequalities, revealing the ‘dark side’ of green development in peripheral regions. |

| Political Ecology framework for Sustainable Energy Transition (PESET), EJ, postcolonial/Indigenous | Develop a political ecology perspective to show how power relations embedded in energy systems shape unequal transition pathways, privileging certain actors while marginalising communities and alternative knowledges. |

| EJ, institutional work, imaginaries | Examine how ET can be aligned with social equity by identifying institutional, governance, and participatory conditions necessary to avoid reproducing existing injustices. |

| EJ, decolonial/postcolonial, Indigenous | Argues for decolonising EJ by grounding it in local, Indigenous, and community-based struggles, challenging universalist EJ frameworks rooted in Western epistemologies. |

| Transitional EJ, Indigenous perspectives | Analyse how Indigenous ontologies and historical experiences in Latin America shape alternative energy futures, revealing tensions between extractivist transition models and relational worldviews. |

| Green extractivism, visual political ecology | Shows that renewable energy projects can produce ‘green dispossession’ by aestheticising extractivism and masking territorial, cultural, and ontological violence against Indigenous peoples in the name of decarbonisation |

| Coloniality/postcolonial, EJ, green extractivism | Introduce the concept of ‘energy colonialism’ to analyse how corporate-led ET reproduce asymmetric power relations, extractivist practices, and territorial inequalities across both the Global South and North. |

| EJ | Argue that a just ET requires community-centric local governance frameworks that prioritise participation, decentralised decision-making, and local control over energy systems. |

| Green extractivism, EJ, geopolitical metabolism, coloniality | Demonstrate how green extractivism operates through colonial logics of dispossession by analysing nickel extraction as a critical mineral underpinning decarbonisation, reinforcing centre–periphery inequalities in the ET. |

| Coloniality/postcolonial, green extractivism | Calls for a new research agenda on green colonialism in Latin America, highlighting how the expansion of renewable energy risks reproducing historical patterns of domination, dependency, and socio-environmental conflict. |

| Article | Geographic Focus | Energy Technology/ Resource | Primary Findings on Burden Redistribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Portugal (peripheral rural territories) | Lithium mining | Lithium mining for the ET creates green sacrifice zones, reproducing violence and injustice in peripheral territories. |

| Global South (Sub-Saharan Africa) | Solar home systems, clean cookstoves | Power and resource capture in low-carbon transitions. Marginalised groups risk exclusion. Need for inclusive frameworks. |

| Germany, South Africa | Renewable energy infrastructures | Renewable energy may worsen social equity; ‘agency’ and institutions influence burden sharing. |

| Global South (Latin America) | General (energy landscapes) | Western-centric transitions perpetuate colonial power; there is a need for decolonial, place-based justice. |

| Latin America (Indigenous communities) | General (green transition) | Historical violence and dispossession persist; self-determination and relationality are needed for justice. |

| La Guajira, Colombia (Wayúu territory) | Wind energy | Wind projects reproduce extractivist impacts; Wayúu face dispossession and delegitimisation. |

| Mexico, Norway, Spain, Western Sahara | Renewable energy megaprojects | Energy colonialism persists; megaprojects cause dispossession, land grabbing, and resistance. |

| India (Global South), UK, USA | Coal phase-out, renewables | Local governance is marginalised; top-down transitions externalise burdens to local communities. |

| Not specified (focus on formerly colonised countries) | Nickel (transition minerals) | Decarbonisation reinforces colonial extractivism; dispossession and sacrifice zones in the periphery. |

| Latin America (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Mexico) | Lithium, green hydrogen, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) | Green colonialism perpetuates resource extraction, social-ecological inequalities, and violent suppression. |

| Article | Burden Type | Redistribution Mechanism | Affected Communities | Legitimation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social, ecological, geopolitical | Green grabbing, infrastructural colonisation | Rural communities in Northern Portugal | ‘Green’ transition discourse, sacrifice zone framing |

| Social, economic | Resource capture, exclusion from innovation | Marginalised groups in the Global South | Inclusive innovation rhetoric, Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framing |

| Social equity | Institutional agency, discursive cycles | Local communities in Germany and South Africa | Alignment with equity goals, but negative outcomes |

| Social, cultural | Western-centric policy, knowledge exclusion | Indigenous/peasant communities, Global South | Universalised justice, modernity narratives |

| Social, ecological, historical | Historical violence, governance exclusion | Indigenous Peoples, Latin America | Transitional justice, relationality |

| Social, ecological, cultural | Green extractivism, visual legitimation | Wayúu (La Guajira, Colombia) | Aestheticisation, delegitimisation of demands |

| Social, ecological, geopolitical | Land grabbing, dispossession, centralisation | Indigenous/rural Communities (Mexico, Norway, Spain, Western Sahara) | Climate mitigation discourse, capitalist development |

| Social, governance | Top-down interventions, elite capture | Local communities, India | Technocratic transition, lack of participation |

| Social, ecological, geopolitical | Extractivism, predatory appropriation | Formerly colonised countries | Socioecological fix, Green New Deal rhetoric |

| Social, ecological, geopolitical | Green colonialism, externalisation | Latin American communities, Indigenous | Techno-optimism, Eurocentric modernity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Poque González, A.B.; Masip Macia, Y. Energy Justice, Critical Minerals, and the Geopolitical Metabolism of the Global Energy Transition: Insights from Copper Extraction in Chile and Peru. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021032

Poque González AB, Masip Macia Y. Energy Justice, Critical Minerals, and the Geopolitical Metabolism of the Global Energy Transition: Insights from Copper Extraction in Chile and Peru. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021032

Chicago/Turabian StylePoque González, Axel Bastián, and Yunesky Masip Macia. 2026. "Energy Justice, Critical Minerals, and the Geopolitical Metabolism of the Global Energy Transition: Insights from Copper Extraction in Chile and Peru" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021032

APA StylePoque González, A. B., & Masip Macia, Y. (2026). Energy Justice, Critical Minerals, and the Geopolitical Metabolism of the Global Energy Transition: Insights from Copper Extraction in Chile and Peru. Sustainability, 18(2), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18021032