Where Is the Best Place to Live in the European Union? A Synthetic Assessment of External Residential Environmental Quality from a Sustainability Perspective by Degree of Urbanisation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Do factors that reduce the quality of the external residential environment for households (such as noise, air pollution, and crime) vary significantly depending on the level of urbanisation and regional affiliation in the EU?

- -

- What is the level, 2014–2023 change, and spatial variation in the synthetic indicator of perceived external residential environmental quality of households in EU countries, broken down by level of urbanisation and regional affiliation? Do the results confirm the predominance of Western Europe in this regard?

2. External Residential Environmental Quality as a Component of Household Living Conditions: Theoretical Framework

3. Research Materials and Methods

- -

- cities—densely populated areas where at least 50% of the population resides in an urban centre,

- -

- towns and suburbs (towns)—areas of medium population density where at least 50% of the population lives in urban clusters but which are not classified as cities,

- -

- rural areas—sparsely populated areas where more than 50% of the population lives in the countryside.

4. Results

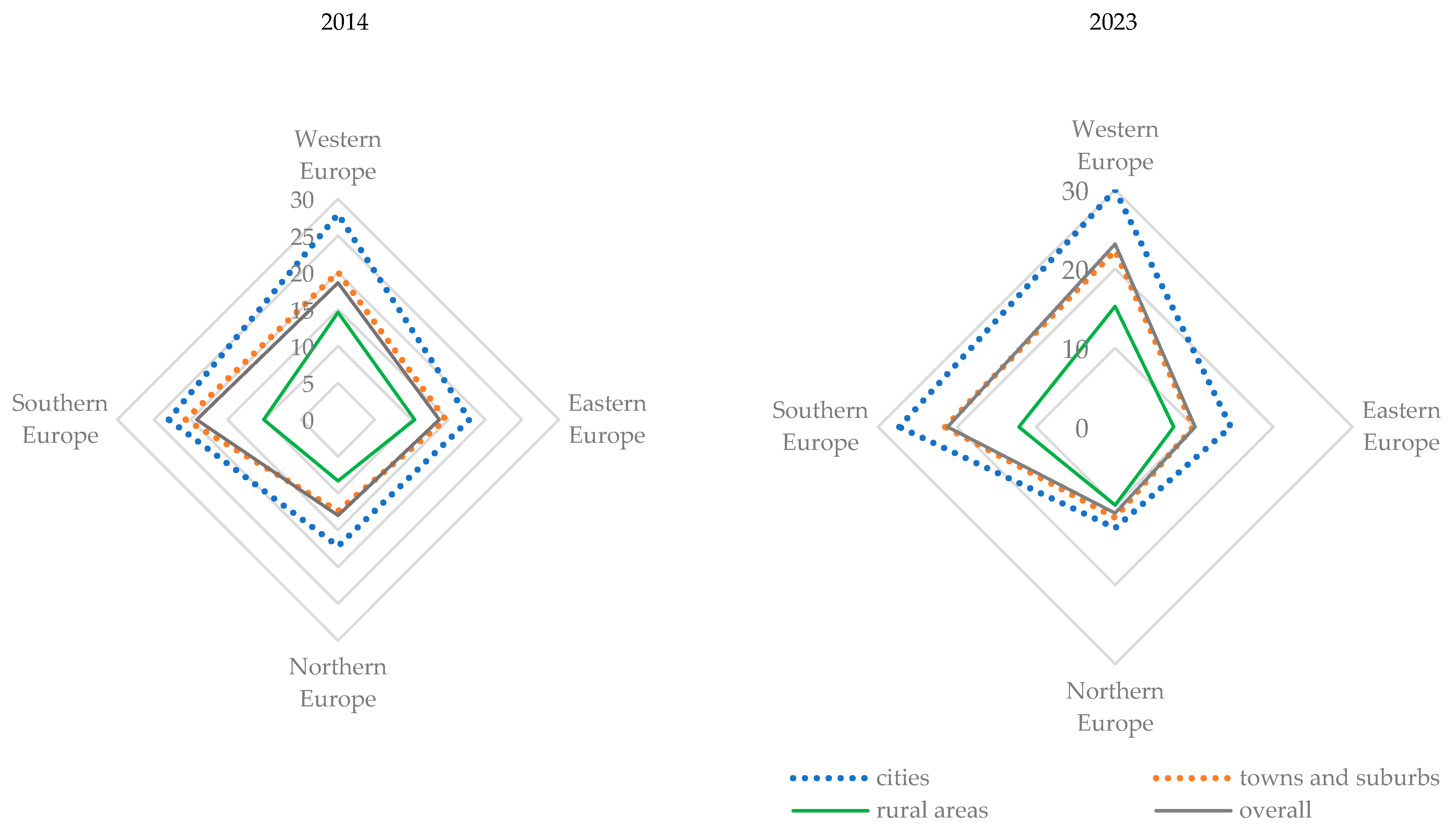

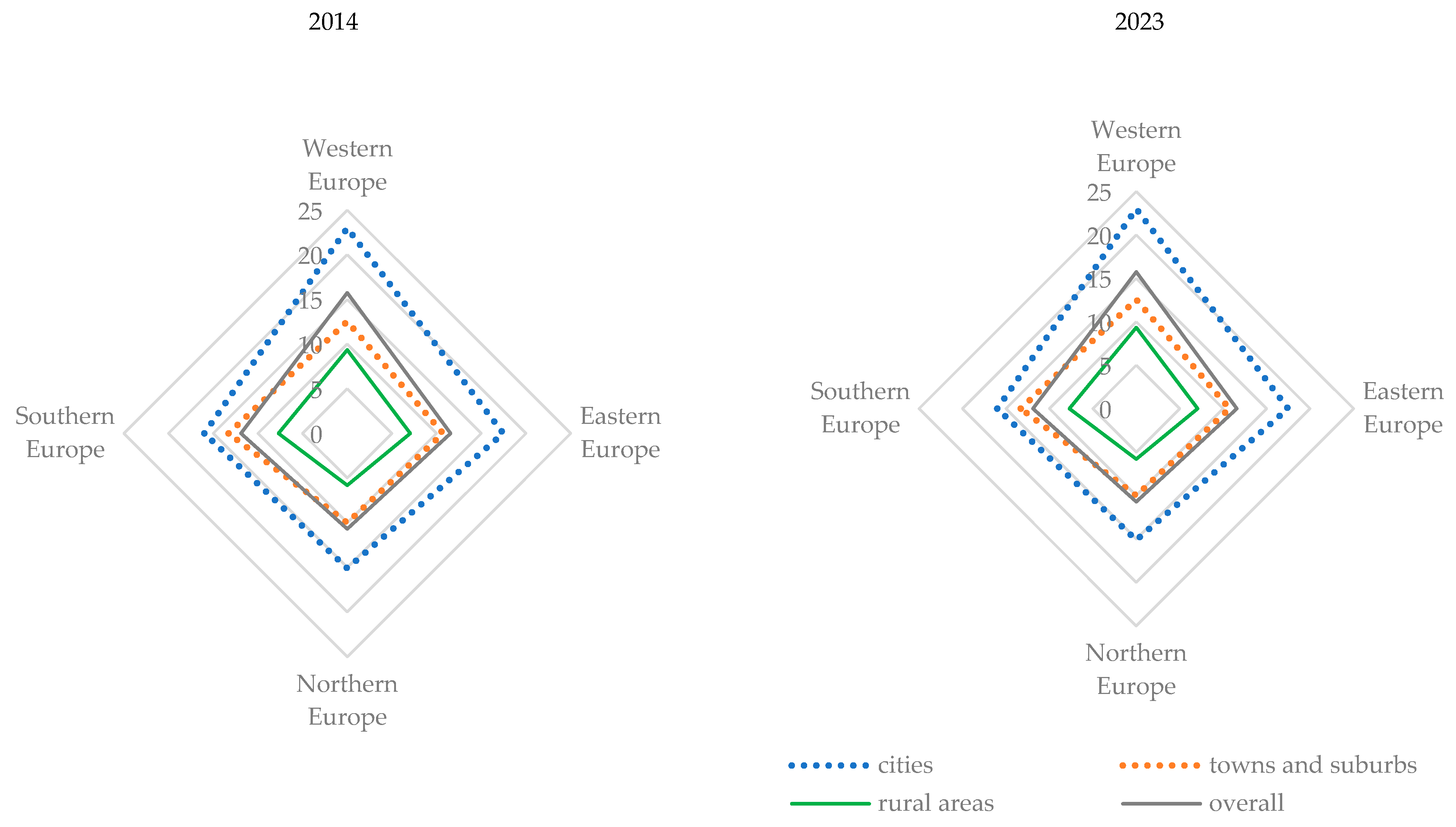

4.1. Noise, Pollution, and Crime in the Residential Environment of Households in EU Countries—Spatial Analysis by Level of Urbanisation

| List | Results of the Kruskal–Wallis Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Noise from neighbours or from the street | ||

| Cities | 12.08 | 0.007 |

| Towns and suburbs | 11.64 | 0.009 |

| Rural areas | 7.90 | 0.048 |

| Pollution, grime or other environmental problems | ||

| Cities | 7.42 | 0.059 |

| Towns and suburbs | 2.52 | 0.473 |

| Rural areas | 2.52 | 0.471 |

| Crime, violence or vandalism in the area | ||

| Cities | 10.90 | 0.012 |

| Towns and suburbs | 4.84 | 0.184 |

| Rural areas | 5.31 | 0.151 |

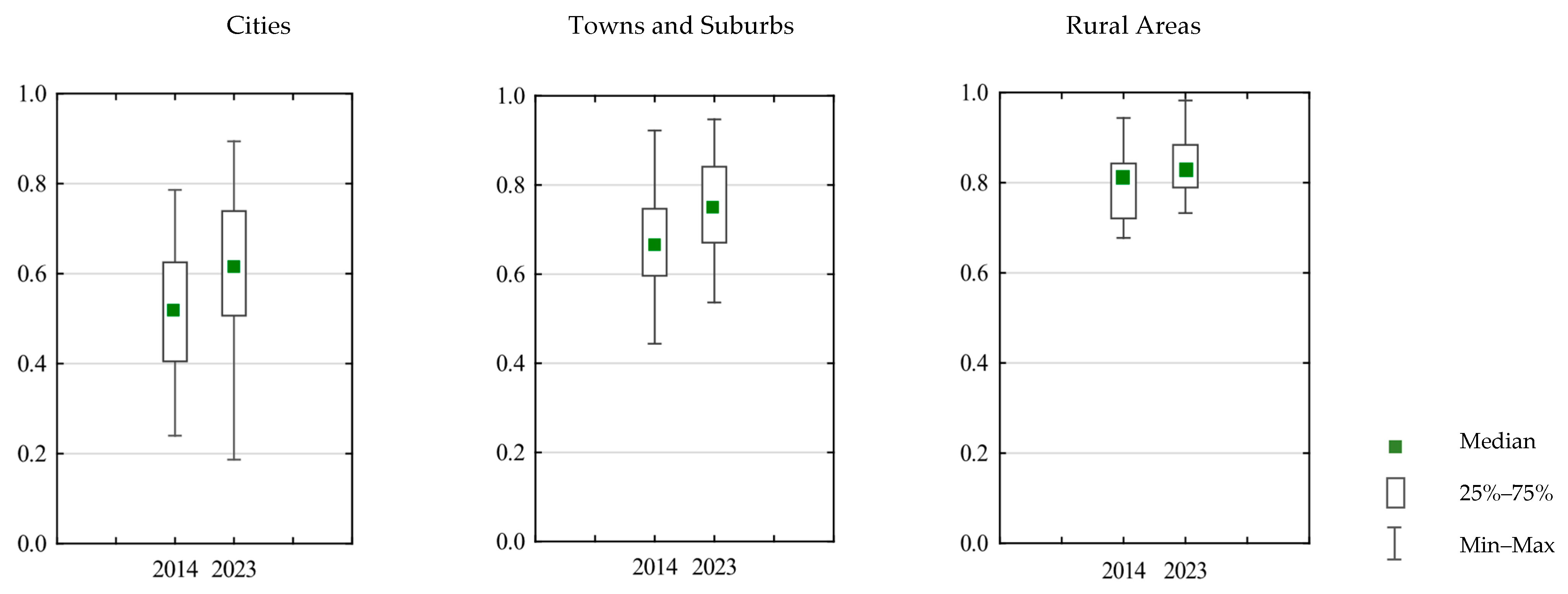

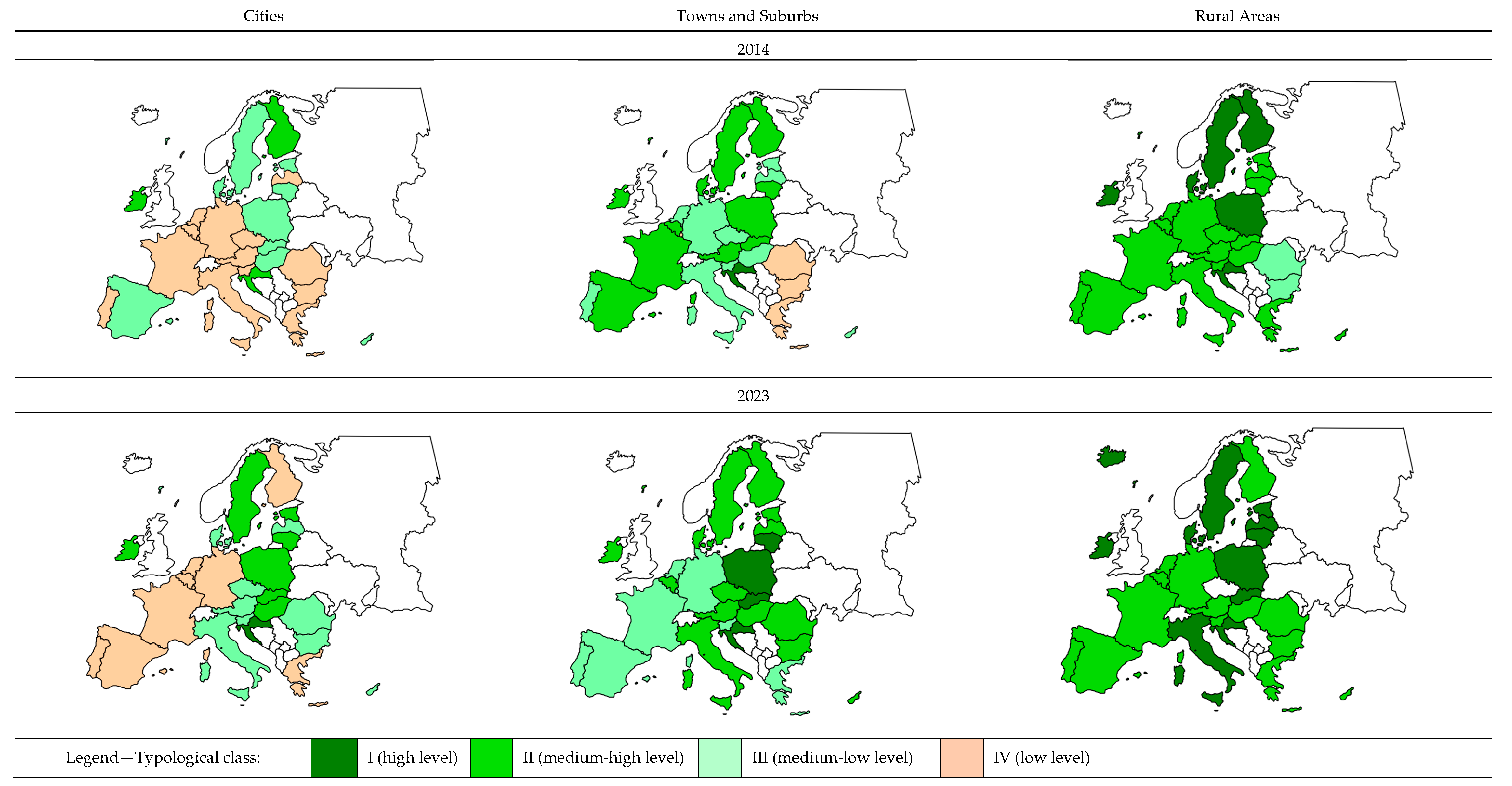

4.2. External Residential Environmental Quality of Households in EU Countries by Degree of Urbanisation—A Synthetic Assessment

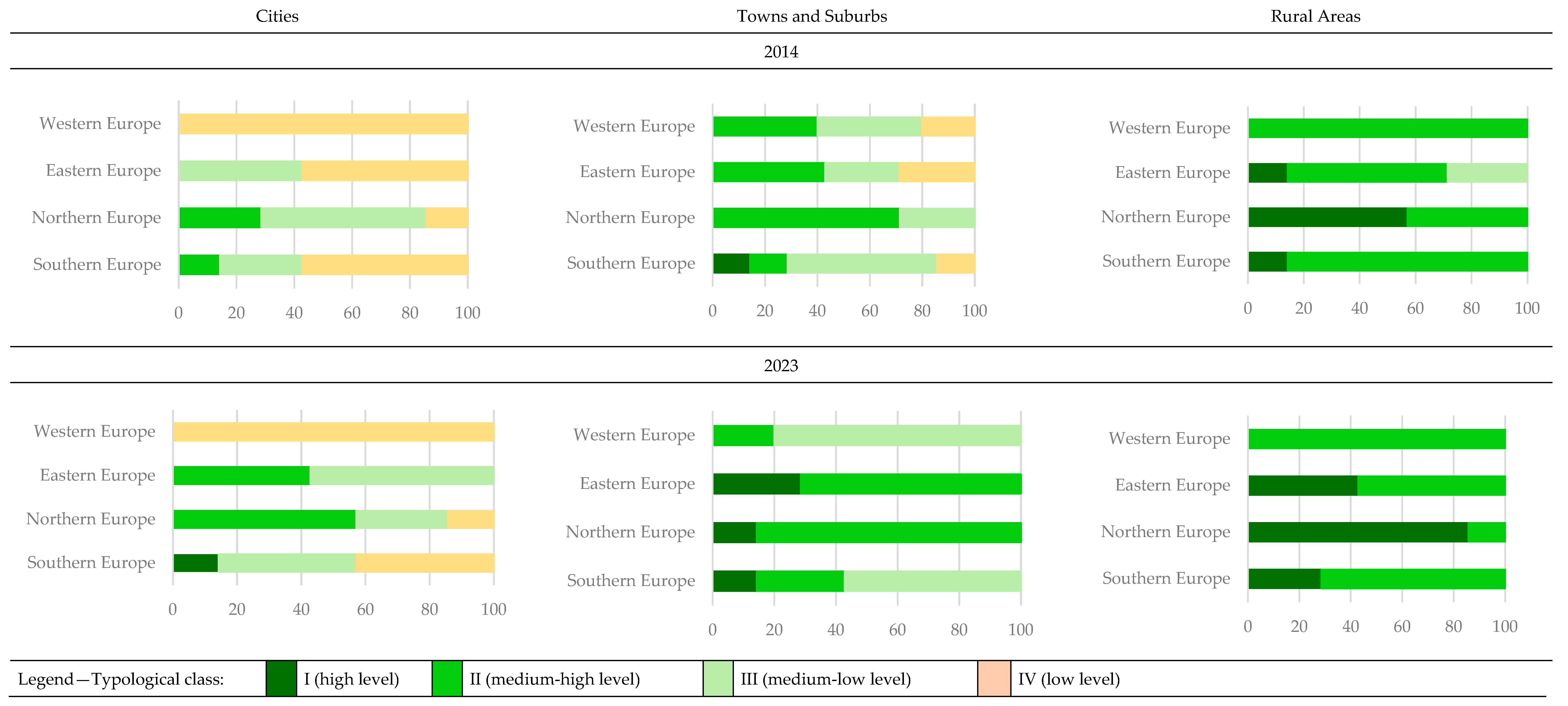

- -

- class I (high level of external residential environmental quality of households)—includes units in which the indicator reaches the highest values, which ow level of perceived environmental and social disturbances (noise, pollution, and crime) and a favourable quality of the external residential environment;

- -

- class II (medium-high level)—denotes moderately favourable external residential environmental conditions, with a limited impact of factors reducing quality of life;

- -

- class III (medium-low level)—indicates the presence of significant perceived environmental and social problems in the residential surroundings, which may affect the daily functioning of residents;

- -

- class IV (low level)—includes areas with the lowest indicator values, where the accumulation of unfavourable perceived environmental and social disturbances significantly reduces the perceived quality of the external residential environment.

5. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Fyfe, C.; Nathan, K.; Keall, M.; Riggs, L.; Pierse, N. The Effects of Housing on Health and Well-Being in Aotearoa New Zealand. N. Z. Popul. Rev. 2021, 47, 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, L.; Fuchs, L.M.; Schupp, J.; von Scheve, C. Living Conditions and the Mental Health and Well-Being of Refugees: Evidence from a Large-Scale German Survey. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2020, 22, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, N.S.; Osman, M.M.; Bachok, S.; Farhanah, N.; Abdullah, M.F. Perceptual Study on Conventional Quality of Life Indicators. Plan. Malays. J. 2018, 16, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćwiek, M.; Ulman, P.; Sadko, M. Ocena warunków mieszkaniowych w Europie z zastosowaniem metody TOPSIS. Ekonomista 2024, 3, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimed-Ochir, O.; Ikaga, T.; Ando, S.; Ishimaru, T.; Kubo, T.; Murakami, S.; Fujino, Y. Effect of Housing Condition on Quality of Life. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szydło, R.; Ćwiek, M.; Wiśniewska, S.; Koczyński, M. Multidimensional Inventory of Students’ Quality of Life-Short Version (MIS-QOL-S). Int. J. Qual. Res. 2021, 15, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Chadchan, J.; Mishra, S.K. Review of Concepts, Tools and Indices for the Assessment of Urban Quality of Life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Adopted by the General Assembly on 10 December 1948; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1948; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Adopted and Opened for Signature, Ratification and Accession by General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI), 16 December 1966; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1966; Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Council of Europe. European Social Charter (Revised) (ETS No. 163); Adopted in Strasbourg, 3 May 1996; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1996; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168007cde2 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- United Nations. Declaration on Social Progress and Development; Proclaimed by General Assembly Resolution 2542 (XXIV) of 11 December 1969. United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1969. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/progress.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (UNCHS). The Habitat Agenda: Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements. In Proceedings of the Adopted at the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II), Istanbul, Turkey, 3–14 June 1996; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 1996; Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/habitat/istanbul1996 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kozera, A.; Kozera, C. Poziom życia ludności i jego zróżnicowanie w krajach Unii Europejskiej. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2011, 22, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Kozera, C. Does the Level of Living Conditions of the Population Depend on the Place of Residence? Rural and Urban Perspective of European Union Countries. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2024, 27, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.; van Steen, G. Housing Poverty and Income Poverty in England and the Netherlands. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Kalinowski, S. Assessing the Level of the Material Deprivation of European Union Countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Kozera, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Wołoszyn, A. Warunki Mieszkaniowe Gospodarstw Domowych w Polsce; CeDeWu: Warszawa, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Matel, A. The “New” Housing Deprivation Gap of EU Countries. Optimum. Econ. Stud. 2024, 4, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowski, P.; Broda-Wysocki, P. Ubóstwo Mieszkaniowe: Oblicza, Trendy, Wyzwania. Polityka Społeczna 2017, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, C.; Ayala, L. Multidimensional Housing Deprivation Indices with Application to Spain. Appl. Econ. 2008, 40, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora-Fernandez, D. Deprywacja Mieszkaniowa w Polsce na Podstawie Wybranych Czynników. Space–Soc.–Econ. 2018, 26, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hick, R.; Pomati, M.; Stephens, M. Severe Housing Deprivation in the European Union: A Joint Analysis of Measurement and Theory. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 1271–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, L.; Bárcena-Martín, E.; Cantó, O.; Navarro, C. COVID-19 Lockdown and Housing Deprivation across European Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 298, 114839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy. Territorial Agenda 2030: A Future for All Places; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/brochure/territorial_agenda_2030_en.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Kozera, A.; Kozera, C.; Hadyński, J. The Level of Housing Conditions in the European Union Countries. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 930–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekut, M. Housing Conditions in European One-Person Households. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolennikova, N. Specifics of Russians’ Perception of Housing Conditions and Housing Inequality: Dynamics and Factors. Econ. Soc. Changes Facts Trends Forecast. 2024, 17, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, K.K.; Ramachandran, K.V. Sustainability of Housing Conditions in Rural Kerala. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Res. 2024, 9, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valceanu, I.C.; Ogarleanu, M.; Zgura, I.; Popescu, G.M.; Geicu, A. Housing conditions and housing quality in Romania. Rom. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2011, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Alpopi, C.; Manole, C.; Ciovica, C. Quality of life and housing conditions—European Union vs. Romania. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 10, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, N.; Eastaway, M.P. Sustainable housing in the urban context: International sustainable development indicator sets and housing. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 87, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, P.; van Lindert, P. Sustainable housing and the urban poor. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2016, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumaya, J.Q.; Motlak, J.B. Sustainable housing indicators and improving the quality of life: The case of two residential areas in Baghdad City. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 754, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, H.; Wojewódzka-Wiewiórska, A. Dimensions of housing deprivation in Poland: A rural-urban perspective. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241293258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.A. Sustainable housing development: Role and significance of satisfaction aspect. City Territ. Archit. 2020, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Derqui, D.; Torres-Téllez, J.; Montero-Soler, A. Effects of housing deprivation on health: Empirical evidence from Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.P.; Adabre, M.A. Bridging the gap between sustainable housing and affordable housing: The required critical success criteria (CSC). Build. Environ. 2019, 151, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.A. Is a fixer-upper actually a downer? Homeownership, gender, work on the home, and subjective wellbeing. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 342–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleńczuk-Paszel, A.; Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. Zmiany warunków mieszkaniowych na obszarach wiejskich w Polsce w latach 2002–2014. Rocz. Nauk. Ekon. Rol. I Rozw. Obsz. Wiej. 2017, 104, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Housing in Chinese urban villages: The dwellers, conditions and tenancy informality. Hous. Stud. 2016, 31, 852–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom. In The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change, 2nd ed.; Roberts, J.T., Bellone Hite, A., Chorev, N., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- van Kamp, I.; Leidelmeijer, K.; Marsman, G.; de Hollander, A. Urban environmental quality and human well-being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacione, M. Urban environmental quality and human wellbeing—A social geographical perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Fornara, F.; Bonnes, M. Perceived residential environment quality in middle- and low-extension Italian cities. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 56, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marans, R.W.; Rodgers, W. Toward an understanding of community satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 1975, 7, 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Rahtz, D.R.; Cicic, M.; Underwood, R. A method for assessing residents’ satisfaction with community-based services: A quality-of-life perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2000, 49, 279–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gyourko, J.; Mayer, C.; Sinai, T. Superstar cities. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2013, 5, 167–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Albouy, D. What Are Cities Worth? Land Rents, Local Productivity, and the Total Value of Amenities; NBER Working Paper No. 14981; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w14981 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Ellen, I.G.; Turner, M.A. Does neighborhood matter? Assessing recent evidence. Hous. Policy Debate 1997, 8, 833–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Hulchanski, J.D.; Hwang, S. The housing/health relationship: What do we know? Can. J. Public Health 2000, 91, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Morenoff, J.D.; Gannon-Rowley, T. Assessing “Neighborhood Effects”: Social Processes and New Directions in Research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 443–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, P.; Faber, J.W. Where, when, why, and for whom do residential contexts matter? Moving Away from the Dichotomous Understanding of Neighborhood Effects. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.J. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, R.D. Environmental justice: It’s more than waste facility siting. Soc. Sci. Q. 1993, 74, 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Brulle, R.J.; Pellow, D.N. Environmental justice: Human health and environmental inequalities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohai, P.; Pellow, D.; Roberts, J.T. Environmental justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M.; Cameron, S.; Merridew, T.; Pichler, F. Urban–rural differences in quality of life across the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, H.; Hanssen, G.S.; Andersen, B.; Harboe, L.; Ljunggren, J.; Røe, P.G.; Wullf-Wathne, M. Nordic responses to urban challenges of the 21st century. Nord. J. Urban Stud. 2021, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfarsson, G.F.; Steinbrenner, A.; Valsson, T.; Kim, S. Urban household travel behavior in a time of economic crisis: Changes in trip making and transit importance. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 49, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagbert, P. It’s just a matter of adjustment: Residents’ perceptions and the potential for low-impact home practices. Hous. Theory Soc. 2016, 33, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methodology—Income and Living Conditions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/income-and-living-conditions/methodology (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Eurostat Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, F. Metody Taksonomiczne w Rozpoznawaniu Typów Ekonomicznych Rolnictwa i Obszarów Wiejskich; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Miedema, H.M.E.; Vos, H. Exposure-response relationships for transportation noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998, 104, 3432–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Europe. Burden of Disease from Environmental Noise: Quantification of Healthy Life Years Lost in Europe; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Genève, Switzerland, 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326424 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Hänninen, O.; Knol, A.B.; Jantunen, M.; Lim, T.; Conrad, A.; Rappolder, M.; Carrer, P.; Fanetti, A.; Kim, R.; Buekers, J. Environmental burden of disease in Europe: Assessing nine risk factors in six countries. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Tuomi, T.; Turunen, A.W.; Tiittanen, P.; Lanki, T. Exposure-response functions for the effects of traffic noise on self-reported annoyance and sleep disturbance in Finland: Effect of exposure estimation method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duany, A.; Plater-Zyberk, E.; Speck, J. Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A.C. Comparing states with and without growth management: Analysis based on indicators with policy implications. Land Use Policy 1999, 16, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Kang, J. Relationship between urban development patterns and noise complaints in England. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 48, 1632–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.R.; McKay, H.D. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J.; Groves, W.B. Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 94, 774–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, I.; Szczecińska, B. Crime in the countries of the European Union—Taxonomic analysis. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2025, 219, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummelsheim, D.; Hirtenlehner, H.; Jackson, J.; Oberwittler, D. Social insecurities and fear of crime: A cross-national study on the impact of welfare state policies on crime-related anxieties. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 27, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, C.; Häyrinen, L.; Strandell, A.; Lahtinen, K. Environmental worries as drivers of housing preferences: Views of Finnish citizens. Cities 2025, 167, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human–environment interactions in urban green spaces—A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, A.; Cermakova, K.; Kalinowski, S.; Hromada, E.; Szczygieł, O. “The future depends on what we do in the present”-Development positions of EU countries by levels of sustainable development and living standards. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Specification | Details and Calculation Formulas | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Selection of simple features for the study | Criteria for feature selection: data availability (by degree of urbanisation), substantive criteria, and statistical criteria |

| Step 2 | Normalisation of simple feature values | for destimulants: |

| where: —value of the k-th feature in the i-th object, —minimum value of the k-th feature, —maximum value of the k-th feature. | ||

| Step 3 | Determination of the coordinates of model objects—the development pattern and anti-pattern | . |

| Step 4 | Calculation of the distance of each object (country) from the development pattern and anti-pattern using the Euclidean distance | , |

| Step 5 | Calculation of the synthetic measure using the TOPSIS method | |

| Step 6 | Identification of typological classes using a statistical approach (based on the mean and standard deviation of the synthetic measure values) | class I (high level): class II (medium high level): class III (medium low level): class IV (low level): |

| Specification | 2014 | 2023 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | Overall | Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | Overall | |

| Min | 12.9 | 8.4 | 4.9 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 3.7 | 6.7 |

| Q1 | 17.4 | 13.2 | 8.7 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 8.9 | 7.0 | 10.1 |

| Median | 20.2 | 14.9 | 10.4 | 15.6 | 20.5 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 14.9 |

| Average | 22.0 | 16.0 | 10.7 | 16.3 | 21.5 | 15.7 | 10.5 | 16.4 |

| Q3 | 27.9 | 20.9 | 12.1 | 19.1 | 29.7 | 21.5 | 13.9 | 21.7 |

| Max | 33.8 | 26.2 | 17.2 | 25.9 | 42.4 | 32.5 | 19.8 | 30.2 |

| Range | 20.9 | 17.8 | 12.3 | 17.0 | 33.9 | 25.6 | 16.1 | 23.5 |

| Specification | 2014 | 2023 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | Overall | Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | Overall | |

| Min | 7.1 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 4.2 |

| Q1 | 13.8 | 8.9 | 6.1 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 7.0 | 4.9 | 7.8 |

| Median | 17.2 | 13.1 | 8.9 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 9.1 | 6.9 | 10.6 |

| Average | 18.6 | 12.8 | 8.6 | 13.4 | 15.0 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 11.0 |

| Q3 | 21.7 | 16.5 | 10.9 | 15.8 | 17.6 | 14.5 | 9.1 | 14.8 |

| Max | 36.3 | 24.9 | 17.6 | 23.2 | 35.3 | 17.1 | 12.3 | 20.5 |

| Range | 29.2 | 22.1 | 14.4 | 18.7 | 29.1 | 13.5 | 9.6 | 16.3 |

| Specification | 2014 | 2023 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | Overall | Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | Overall | |

| Min | 6.3 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| Q1 | 14.0 | 9.0 | 5.3 | 9.9 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 5.8 |

| Median | 17.5 | 11.3 | 7.5 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 7.0 |

| Average | 17.9 | 11.9 | 7.7 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 6.9 | 5.0 | 8.6 |

| Q3 | 22.4 | 13.9 | 9.7 | 15.5 | 17.7 | 10.1 | 6.6 | 11.7 |

| Max | 33.4 | 25.8 | 19.9 | 26.8 | 26.9 | 16.7 | 16.4 | 20.9 |

| Range | 27.1 | 24.4 | 18.9 | 24.3 | 24.3 | 15.3 | 16.0 | 19.5 |

| Specification | Number/ Percentage | Typological Class/Level External Residential Environmental Quality | Overall | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | |||

| High | Medium-High | Medium-Low | Low | |||

| qi ≥ 0.858 | 0.694 ≤ qi ˂ 0.858 | 0.530 ≤ qi ˂ 0.694 | qi < 0.530 | |||

| 2014 | ||||||

| Cities | Number | 0 | 3 | 9 | 14 | 26 countries/100% |

| % | 0.0 | 11.5 | 34.6 | 53.8 | ||

| Towns and suburbs | Number | 1 | 11 | 10 | 4 | |

| % | 3.8 | 42.3 | 38.5 | 15.4 | ||

| Rural areas | Number | 6 | 18 | 2 | 0 | |

| % | 23.1 | 69.2 | 7.7 | 0.0 | ||

| 2023 | ||||||

| Cities | Number | 1 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 26 countries/ 100% |

| % | 3.8 | 26.9 | 34.6 | 34.6 | ||

| Towns and suburbs | Number | 4 | 14 | 8 | 0 | |

| % | 15.4 | 53.8 | 30.8 | 0.0 | ||

| Rural areas | Number | 11 | 12 | 13 | 0 | |

| % | 42.3 | 46.2 | 11.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Country | Cities | Towns and Suburbs | Rural Areas | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2023 | Change in Ranking Position | Change in Class | 2014 | 2023 | Change in Ranking Position | Change in Class | 2014 | 2023 | Change in Ranking Position | Change in Class | |||||||||||||

| qi | Position | Class | qi | Position | Class | qi | Position | Class | qi | Position | Class | qi | Position | Class | qi | Position | Class | |||||||

| Croatia | 0.786 | 52 | II | 0.894 | 13 | I | 39 | 1 | 0.922 | 7 | I | 0.947 | 3 | I | 4 | 0 | 0.943 | 4 | I | 0.982 | 1 | I | 3 | 0 |

| Poland | 0.604 | 116 | III | 0.760 | 64 | II | 52 | 1 | 0.742 | 69 | II | 0.904 | 9 | I | 60 | 1 | 0.896 | 12 | I | 0.957 | 2 | I | 10 | 0 |

| Italy | 0.374 | 149 | IV | 0.686 | 93 | III | 56 | 1 | 0.619 | 113 | III | 0.841 | 30 | II | 83 | 1 | 0.838 | 32 | II | 0.936 | 5 | I | 27 | −1 |

| Slovakia | 0.617 | 114 | III | 0.820 | 37 | II | 77 | 1 | 0.701 | 88 | II | 0.925 | 6 | I | 82 | 1 | 0.824 | 36 | II | 0.907 | 8 | I | 28 | −1 |

| Estonia | 0.631 | 107 | III | 0.805 | 45 | II | 62 | 1 | 0.636 | 104 | III | 0.832 | 34 | II | 70 | 1 | 0.840 | 31 | II | 0.901 | 10 | I | 21 | −1 |

| Lithuania | 0.625 | 111 | III | 0.742 | 70 | II | 41 | 1 | 0.747 | 68 | II | 0.862 | 22 | I | 46 | 1 | 0.843 | 27 | II | 0.899 | 11 | I | 16 | −1 |

| Czechia | 0.525 | 132 | IV | 0.638 | 102 | III | 30 | 1 | 0.653 | 100 | III | 0.777 | 59 | II | 41 | 1 | 0.810 | 41 | II | 0.884 | 15 | I | 26 | −1 |

| Denmark | 0.534 | 129 | III | 0.630 | 108 | III | 21 | 0 | 0.827 | 35 | II | 0.856 | 25 | II | 10 | 0 | 0.878 | 17 | I | 0.881 | 16 | I | 1 | 0 |

| Sweden | 0.628 | 110 | III | 0.739 | 71 | II | 39 | 1 | 0.779 | 57 | II | 0.857 | 24 | II | 33 | 0 | 0.874 | 19 | I | 0.868 | 20 | I | −1 | 0 |

| Ireland | 0.711 | 82 | II | 0.757 | 65 | II | 17 | 0 | 0.810 | 40 | II | 0.729 | 77 | II | −37 | 0 | 0.875 | 18 | I | 0.867 | 21 | I | −3 | 0 |

| Latvia | 0.450 | 141 | IV | 0.575 | 123 | III | 18 | 1 | 0.665 | 98 | III | 0.763 | 62 | II | 36 | 1 | 0.708 | 84 | II | 0.861 | 23 | I | 61 | −1 |

| Bulgaria | 0.405 | 147 | IV | 0.565 | 124 | III | 23 | 1 | 0.528 | 131 | IV | 0.791 | 50 | II | 81 | 2 | 0.677 | 95 | III | 0.846 | 26 | II | 69 | −1 |

| Belgium | 0.284 | 153 | IV | 0.416 | 144 | IV | 9 | 0 | 0.707 | 86 | II | 0.785 | 55 | II | 31 | 0 | 0.709 | 83 | II | 0.843 | 28 | II | 55 | 0 |

| Austria | 0.442 | 143 | IV | 0.601 | 117 | III | 26 | 1 | 0.695 | 90 | II | 0.728 | 79 | II | 11 | 0 | 0.833 | 33 | II | 0.816 | 38 | II | −5 | 0 |

| Romania | 0.365 | 151 | IV | 0.564 | 125 | III | 26 | 1 | 0.514 | 133 | IV | 0.729 | 78 | II | 55 | 2 | 0.692 | 92 | III | 0.809 | 42 | II | 50 | −1 |

| Hungary | 0.537 | 127 | III | 0.737 | 73 | II | 54 | 1 | 0.665 | 99 | III | 0.734 | 74 | II | 25 | 1 | 0.721 | 80 | II | 0.806 | 44 | II | 36 | 0 |

| France | 0.501 | 137 | IV | 0.334 | 152 | IV | −15 | 0 | 0.695 | 91 | II | 0.607 | 115 | III | −24 | −1 | 0.809 | 43 | II | 0.804 | 46 | II | −3 | 0 |

| Spain | 0.595 | 120 | III | 0.529 | 130 | IV | −10 | −1 | 0.774 | 60 | II | 0.671 | 96 | III | −36 | −1 | 0.841 | 29 | II | 0.801 | 47 | II | −18 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 0.511 | 134 | IV | 0.631 | 106 | III | 28 | 1 | 0.666 | 97 | III | 0.680 | 94 | III | 3 | 0 | 0.779 | 58 | II | 0.791 | 49 | II | 9 | 0 |

| Finland | 0.703 | 87 | II | 0.507 | 136 | IV | −49 | −2 | 0.796 | 48 | II | 0.696 | 89 | II | −41 | 0 | 0.890 | 14 | I | 0.789 | 51 | II | −37 | 1 |

| Germany | 0.240 | 155 | IV | 0.411 | 145 | IV | 10 | 0 | 0.555 | 126 | III | 0.628 | 109 | III | 17 | 0 | 0.732 | 76 | II | 0.782 | 56 | II | 20 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 0.464 | 140 | IV | 0.409 | 146 | IV | −6 | 0 | 0.444 | 142 | IV | 0.597 | 118 | III | 24 | 1 | 0.708 | 85 | II | 0.763 | 63 | II | 22 | 0 |

| Greece | 0.247 | 154 | IV | 0.187 | 156 | IV | −2 | 0 | 0.498 | 138 | IV | 0.537 | 128 | III | 10 | 1 | 0.786 | 54 | II | 0.756 | 66 | II | −12 | 0 |

| Cyprus | 0.636 | 103 | III | 0.643 | 101 | III | 2 | 0 | 0.584 | 122 | III | 0.786 | 53 | II | 69 | 1 | 0.769 | 61 | II | 0.750 | 67 | II | −6 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 0.371 | 150 | IV | 0.392 | 148 | IV | 2 | 0 | 0.596 | 119 | III | 0.633 | 105 | III | 14 | 0 | 0.711 | 81 | II | 0.739 | 72 | II | 9 | 0 |

| Portugal | 0.468 | 139 | IV | 0.507 | 135 | IV | 4 | 0 | 0.620 | 112 | III | 0.590 | 121 | III | −9 | 0 | 0.814 | 39 | II | 0.733 | 75 | II | −36 | 0 |

| Typological Class | Noise from Neighbours or from the Street (%) | Pollution, Grime or Other Environmental Problems (%) | Crime, Violence or Vandalism in the Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | |||

| I (high level) | 8.4 | 4.4 | 4.0 |

| II (medium-high level) | 12.7 | 9.1 | 7.7 |

| III (medium-low level) | 17.3 | 14.7 | 13.5 |

| IV (low) | 24.2 | 20.6 | 21.6 |

| Overall | 15.0 | 12.5 | 11.6 |

| 2023 | |||

| I (high) | 7.7 | 5.4 | 2.5 |

| II (medium-high level) | 12.4 | 8.6 | 6.2 |

| III (medium-low level) | 22.2 | 14.5 | 10.9 |

| IV (low) | 30.1 | 17.4 | 19.5 |

| Overall | 13.5 | 9.2 | 6.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kozera, A.; Stanisławska, J. Where Is the Best Place to Live in the European Union? A Synthetic Assessment of External Residential Environmental Quality from a Sustainability Perspective by Degree of Urbanisation. Sustainability 2026, 18, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010088

Kozera A, Stanisławska J. Where Is the Best Place to Live in the European Union? A Synthetic Assessment of External Residential Environmental Quality from a Sustainability Perspective by Degree of Urbanisation. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010088

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozera, Agnieszka, and Joanna Stanisławska. 2026. "Where Is the Best Place to Live in the European Union? A Synthetic Assessment of External Residential Environmental Quality from a Sustainability Perspective by Degree of Urbanisation" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010088

APA StyleKozera, A., & Stanisławska, J. (2026). Where Is the Best Place to Live in the European Union? A Synthetic Assessment of External Residential Environmental Quality from a Sustainability Perspective by Degree of Urbanisation. Sustainability, 18(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010088