Eco-Efficiency Indicators: A Literature Review and Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Eco-Efficiency—State of the Art

3. Eco-Efficiency of Service- and Product-Service Systems Results

4. Research Methodology

- RQ1: Which eco-efficiency indicators were predominantly used/published in the literature since 1999?

- RQ2: How can these indicators be clustered into consistent environmental and economic groups?

- RQ3: Which indicator groups were documented in service/PSS contexts to date, and how are the indicators interconnected based on their co-occurrence patterns?

4.1. Databases and Search Strings

4.2. Raw Database Filtering

4.3. Co-Occurrence Analysis of Indicators

5. Descriptive Analysis of Findings

5.1. Year of Publication

5.2. Journals of Publication

5.3. Geographical Context of Analysis

5.4. Geographical Context of Authors

5.5. Goal of Articles

5.6. Data Sources Applied per Year

6. Environmental Indicators

6.1. Environmental Indicators—Relation to PSS or Service Systems

6.2. Environmental Indicators—Relation to Data Sources

6.3. Environmental Indicators—Relation to the Unit of Analysis

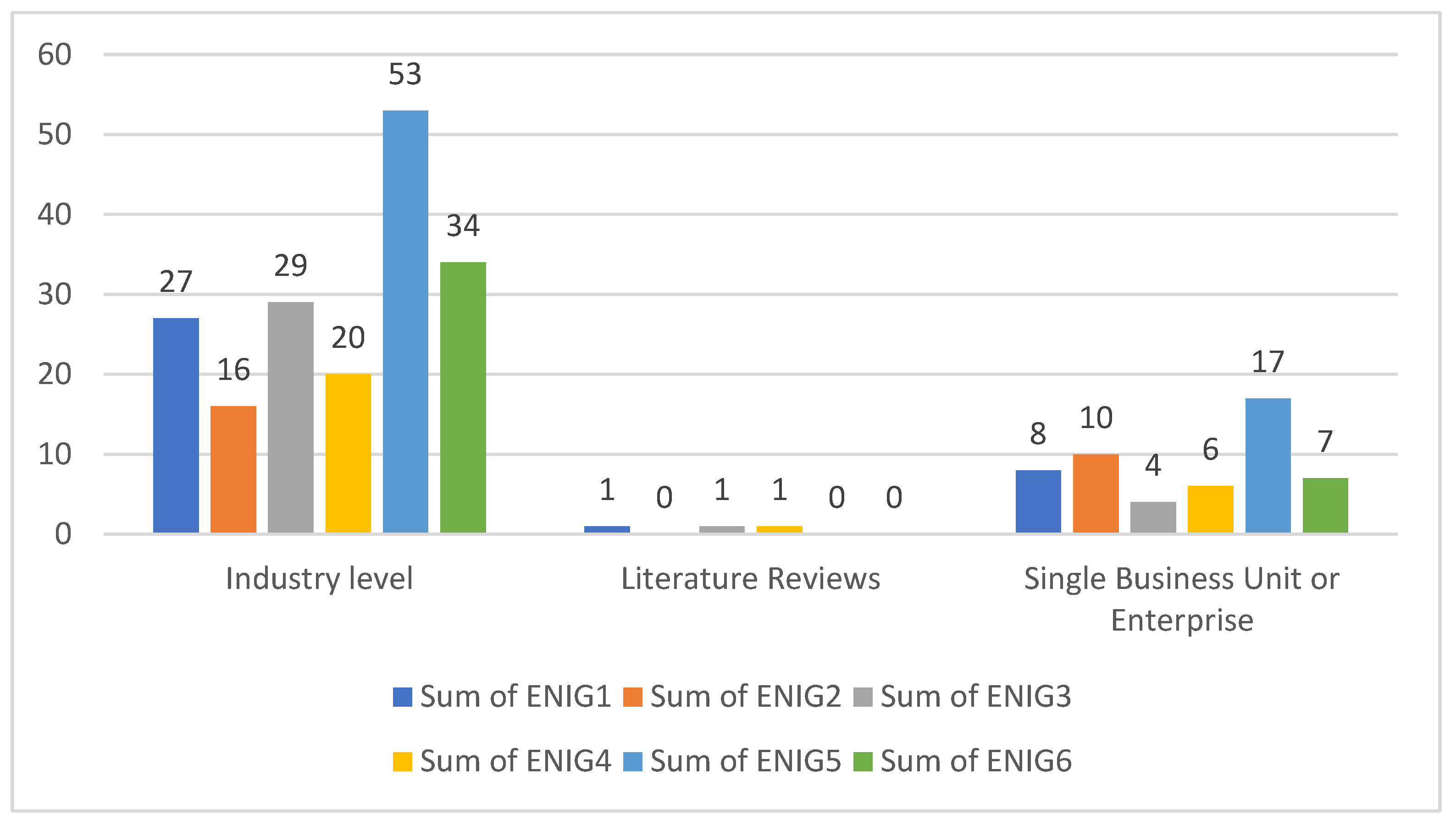

6.4. Environmental Indicators—Relation to Journals

6.5. Environmental Indicators—Descriptive Analysis of Environmental Indicator Groups

7. Economic Indicators

7.1. Economic Indicators—Relation to PSS or Service Systems

7.2. Economic Indicators—Relation to Data Sources

7.3. Economic Indicators—Relation to the Unit of Analysis

7.4. Economic Indicators—Relation to Journals

7.5. Economic Indicators—Descriptive Analysis of Economic Indicator Groups

8. In-Depth Analysis

8.1. Methodological Approach for Co-Occurrence Analysis

8.2. Patterns Among Environmental Indicators

8.3. Patterns Among Economic Indicators

8.4. Cross-Dimensional Insights (ENIG × ECIG)

8.5. Top Weighted Economic and Environmental Indicators Pairs

8.6. Co-Occurrence Analysis of Eco-Efficiency Indicators

8.7. Co-Occurrence of Economic and Environmental Indicators in Service Systems

9. Limitations

10. Discussion

11. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Bibliographic Coupling |

| ECIG | Economic Indicator Group |

| ENIG | Environmental Indicator Group |

| PSS | Product-Service Systems |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Reference | Journal | ENIG | ECIG | Env. Indicator No | Ec. Indicator No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | J. Environ. Manage. | 4 | 2 | E15 | EC7 |

| [31] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 3, 4 | E1, E8, E15 | ||

| [30] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | E1, E6, E8, E24 | ||

| [33] | J. Clean. Prod | 4 | E15 | ||

| [36] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | 1, 3 | E1, E6, E8, E22 | EC1, EC3, EC10 |

| [77] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 3, 4, 6 | 1, 3 | E1, E8, E9, E45 | EC1, EC10 |

| [78] | Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. | 1, 2, 4, 6 | 2 | E1, E6, E37, E39 | EC7 |

| [79] | Sustainability | 2, 4 | 2 | E6, E15 | EC4, EC7 |

| [44] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 | 1, 5 | E1, E6, E8, E37 | EC1, EC17 |

| [80] | Land | 1, 4, 5, 6 | 3, 4 | E1, E15, E22, E34, E36, E43 | EC10, EC14 |

| [81] | Cem. Concr. Compos | 3, 4 | 2 | E11, E15 | EC7 |

| [82] | J. Ind. Ecol. | 1, 3, 4 | 2 | E1, E8, E12 | EC5 |

| [83] | Bus. Strategy Environ. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | 3 | E1, E6, E11, E13, E16, E22, E37 | EC10 |

| [84] | Bus. Strategy Environ. | 1, 3, 4, 6 | 3 | E1, E11, E13, E15, E37, E38, E49 | EC10, EC11, EC12 |

| [85] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | E1, E6, E8, E23, E37, E38 | ||

| [86] | Ecological Economics | 3, 4 | 1, 5 | E8 | EC3, EC17 |

| [87] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | 1, 2, 4, 5 | E1, E5, E6, E8, E10, E14, E15, E17, E21, E25, E26, E31, E34, E43, E46 | EC1, EC4, EC8, EC14, EC18, EC19, EC21 |

| [88] | J. Environ. Manage. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | E1, E6, E7, E12, E15, E18, E23, E40, E43 | ||

| [89] | Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensif. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | E1, E6, E8, E11, E15, E23 | ||

| [90] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 | 1 | E1, E6, E8, E15, E37 | EC1 |

| [91] | Environ. Dev. Sustain. | 4, 5 | 4 | E22 | EC16 |

| [92] | Environ. Dev. Sustain. | 1, 4, 5 | 1, 6 | E1, E22, E23, E29 | EC2, EC23 |

| [93] | J. Clean. Prod | 4 | 4 | E15 | EC15 |

| [94] | Ecological Indicators | 3, 4, 6 | E8, E43 | ||

| [95] | Applied Energy | 1, 2, 4 | 2 | E1, E3, E6, E15 | EC5, EC7 |

| [96] | Sci. Total Environ. | 4, 5 | 2 | E27 | EC6 |

| [97] | J. Clean. Prod | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | 2 | E6, E11, E12, E23, E26, E28, E33, E34, E46 | EC4 |

| [98] | Energies | 4, 5, 6 | E25, E26, E34, E37 | ||

| [99] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 | E2, E11, E35, E36, E38, E42, E43 | ||

| [100] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | 4 | E1, E6, E8, E15, E22, E23, E37, E38 | EC14 |

| [101] | J. Environ. Manage. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | 3 | E1, E6, E8, E15, E16, E19, E34, E37 | EC10, EC24, EC25 |

| [102] | Resour. Energy Econ. | 4 | 2 | E15 | EC6 |

| [103] | J. Ind. Ecol. | 3, 4 | 2 | E8 | EC5, EC9 |

| [104] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 4, 6 | 4 | E1, E3, E15, E47, E48 | EC16 |

| [105] | J. Clean. Prod | 4, 6 | 2, 5 | E15, E37 | EC5, EC7, EC19 |

| [106] | Braz. J. Chem. Eng. | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 | E1, E6, E15, E23, E37 | ||

| [107] | Eur. J. Oper. Res. | 1, 4, 5, 6 | 5 | E1, E15, E30, E31, E32, E33, E44, E46 | EC20 |

| [108] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 4 | 3, 4 | E1, E15 | EC10, EC14 |

| [109] | J. Clean. Prod | 2, 4, 5 | E6, E23, E25 | ||

| [110] | Sci. Total Environ. | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 | 1, 3, 4 | E1, E6, E15, E23, E37 | EC3, EC10, EC13, EC15 |

| [111] | Sustainability | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | E1, E6, E8, E35, E36, E37, E39 | ||

| [112] | J. Clean. Prod | 3, 4 | 4 | E8, E15 | EC14 |

| [113] | Sci. Total Environ. | 1, 4 | 2, 4 | E1 | EC4, EC14 |

| [114] | Braz. Bus. Rev. | 2, 4 | E6 | ||

| [115] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 4, 5 | 3 | E1, E6, E27 | EC10 |

| [116] | ransp. Res. Part D | 4, 5 | 3, 5 | E15, E22 | EC10, EC19 |

| [117] | J. Clean. Prod | 4, 5, 6 | 4 | E20, E21, E25, E26, E31, E34, E46 | EC14 |

| [118] | J. Clean. Prod | 2, 4, 5, 6 | 1,4 | E6, E20, E21, E25, E26, E31, E34, E46 | EC3, EC14 |

| [119] | J. Clean. Prod | 3, 4, 5, 6 | 3 | E8, E22, E37 | EC13 |

| [120] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 3, 4, 6 | 5, 6 | E1, E8, E39 | EC19, EC22 |

| [121] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 4, 6 | E1, E6, E15, E45 | ||

| [122] | J. Clean. Prod | 3, 4, 5 | E8, E15, E22 | ||

| [123] | J. Clean. Prod | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 | E1, E2, E6, E15, E22, E23, E37 | ||

| [124] | Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | E1, E2, E4, E6, E11, E19, E23, E26, E28, E34, E41 |

Appendix A.2

| Indicator | Indicator Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (Consumption) | Energy | E1 |

| Electricity Consumption | E2 | |

| Renewable Energy Consumption | E3 | |

| Energy Recovery | E4 | |

| Total Energy Intensity | E5 | |

| Water (Consumption) | Water | E6 |

| Water Discharge | E7 | |

| Raw Materials (Consumption) | Material/Resources | E8 |

| Total Material Extracted | E9 | |

| Resource Depletion | E10 | |

| (Fossil) Fuel Consumption | E11 | |

| Minerals (Depletion) | E12 | |

| Wood Consumption | E13 | |

| Total Material Intensity | E14 | |

| Greenhouse Gases | Greenhouse Gases | E15 |

| Ozone Depletion Potential | Environmental Damaging Substances | E16 |

| Ozone-depleting Substances | E17 | |

| Water Pollutant | E18 | |

| Photochemical Ozone Synthesis | E19 | |

| Acidifying Emissions | E20 | |

| Photo-oxidant Formation | E21 | |

| Air Pollutants | E22 | |

| Waste Water (Generation/Toxicity) | E23 | |

| Hazardous Waste | E24 | |

| Global Warming | E25 | |

| Eutrophication | E26 | |

| Global Warming Potential | E27 | |

| Climate Change | E28 | |

| Soil Pollution | E29 | |

| Pesticide Risk | E30 | |

| Ecological Toxicity | E31 | |

| Risk Potential | E32 | |

| Terrestrial Ecotoxicity Potential | E33 | |

| Acidification | E34 | |

| Consumption of Fertilizers | E35 | |

| Consumption of Pesticides | E36 | |

| Waste | Others | E37 |

| Atmospheric Emissions | E38 | |

| Emissions (Air, Water, Waste) | E39 | |

| Energy-related Air Emissions | E40 | |

| Waste Gas | E41 | |

| Nitrogen | E42 | |

| Land (Use) | E43 | |

| Erosion | E44 | |

| Environmental Impact | E45 | |

| Human Toxicity | E46 | |

| Population Density | E47 | |

| Labor Productivity | E48 | |

| Solid or Liquid Waste | E49 |

Appendix A.3

| Indicator | Indicator Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Net Sales (Recognized Revenue) | Turnover and Sales Figures | EC1 |

| Transportation Revenue | EC2 | |

| Revenue (Turnover) | EC3 | |

| Unit Price/Unit Cost | Cost and Price | EC4 |

| Additional Cost | EC5 | |

| Cost per m3 | EC6 | |

| Total Costs | EC7 | |

| Life-cycle Cost (LCC) | EC8 | |

| Total Value Added of Products Avoided Cost with Recycling | EC9 | |

| Value Added | Value Added | EC10 |

| Gross Value Added (GVA) | EC11 | |

| Net Value Added (NVA) | EC12 | |

| Economic Value of Product | EC13 | |

| Amount of Production | Productivity and Production | EC14 |

| Total Production Time | EC15 | |

| GDP per Capita | EC16 | |

| Net Sales Minus Costs of Goods and Services Sold | Profit and Profitability | EC17 |

| Operating Profit (EBIT) | EC18 | |

| Profit-to-cost Ratio | EC19 | |

| Net Income | EC20 | |

| Annual ROI | EC21 | |

| Labour Stock | Others | EC22 |

| Safety Metric | EC23 | |

| Population Density | EC24 | |

| Labor Productivity | EC25 |

References

- WBCSD. Achieving Eco-Efficiency in Business: Report of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development; Second Antwerp Eco-efficiency Workshop; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lehni, M.; Schmidheiny, S.; Stigson, B.; Pepper, J. World Business Council for Sustainable Development. In Eco-Efficiency: Creating More Value with Less Impact; WBCSD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; ISBN 9782940240173. [Google Scholar]

- Saling, P.; Kicherer, A.; Dittrich-Krämer, B.; Wittlinger, R.; Zombik, W.; Schmidt, I.; Schrott, W.; Schmidt, S. Eco-efficiency analysis by basf: The method. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsalis, T.A.; Evangelinos, K.I. A framework to measure corporate sustainability performance: A strong sustainability-based view of firm. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauninger, I.; van Husen, C. Eco-Efficiency Environmental Indicators for Service Systems. Procedia CIRP 2025, 136, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Share of Economic Sectors in the Global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 2014 to 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/256563/share-of-economic-sectors-in-the-global-gross-domestic-product/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- World Bank. Share of Employment in Agriculture, Industry, and Services. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-employment-agriculture-industry-services (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Park, Y.S.; Egilmez, G.; Kucukvar, M. A Novel Life Cycle-based Principal Component Analysis Framework for Eco-efficiency Analysis: Case of the United States Manufacturing and Transportation Nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H.; Khalid, M.; Agnelli, S.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B.J.N.Y. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; UN-Dokument A/42/427; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kates, R.W.; Clark, W.C.; Corell, R.; Hall, J.M.; Jaeger, C.C.; Lowe, I.; McCarthy, J.J.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Bolin, B.; Dickson, N.M.; et al. Environment and development. Sustainability science. Science 2001, 292, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saling, P. Eco-efficiency Assessment. In Special Types of Life Cycle Assessment; Finkbeiner, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 115–178. ISBN 978-94-017-7608-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Beckmann, M.; Hansen, E.G. Transdisciplinarity in Corporate Sustainability: Mapping the Field. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, S.; Fließ, S. Nachhaltigkeit als Gegenstand der Dienstleistungsforschung—Ergebnisse einer Zitationsanalyse. In Beiträge zur Dienstleistungsforschung 2016; Büttgen, M., Ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 139–163. ISBN 978-3-658-16463-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Liesen, A.; Barkemeyer, R. Opportunity cost based analysis of corporate eco-efficiency: A methodology and its application to the CO2-efficiency of German companies. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaltegger, S.; Sturm, A. Ökologieorientierte Entscheidungen in Unternehmen. Ökologisches Rechnungswesen Statt Ökobilanzierung: Notwendigkeit, Kriterien, Konzepte; Haupt Verlag AG: Berne, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, J. Development Cooperation Report, 1997: Efforts and Policies of the Members of the Development Assistance Committee, 1998 Edition; Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development: Paris, France, 1998; ISBN 9789264160194. [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone, L.D.; Popoff, F. Eco-Efficiency: The Business Link to Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 0262541092. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. A Manual for the Preparers and Users of Eco-Efficiency Indicators; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, P.; Huber, J.; Levi, H.W. Nachhaltigkeit in Naturwissenschaftlicher und Sozialwissenschaftlicher Perspektive; Hirzel: Stuttgart, Germany, 1995; ISBN 3-8047-1393-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-86547-587-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mechel, C. Entwicklung Eines Multikriteriellen Bewertungssystems zur Messung der Ökoeffizienz—Dargestellt am Beispiel der Wäschereibranche. Doctoral Dissertation, Universität Koblenz-Landau, Landau, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, M.J. The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1957, 120, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidheiny, S. Changing Course: A Global Business Perspective on Development and the Environment, 5th ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; ISBN 0262691531. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, R.J.; Thornton, J.R. On the environmental efficiency of economic systems. Sov. Stud. 1978, 30, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.M.; Haveman, R.H.; Kneese, A.V. The Economics of Environmental Policy; Wiley: New York, NU, USA, 1973; ISBN 047127786X. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Bi, J.; Fan, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Ge, J. Eco-efficiency analysis of industrial system in China: A data envelopment analysis approach. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmondusit, K.; Keartpakpraek, K. Eco-efficiency evaluation of the petroleum and petrochemical group in the map Ta Phut Industrial Estate, Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; de Freitas Dias, R.; Mattos, L.V.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Towards sustainable development through the perspective of eco-efficiency—A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 890–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, K.; Farzipoor, S. Measuring eco-efficiency based on green indicators and potentials in energy saving and undesirable output abatement. Energy Econ. 2015, 50, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdella, G.M.; Kucukvar, M.; Kutty, A.A.; Abdelsalam, A.G.; Sen, B.; Bulak, M.E.; Onat, N.C. A novel approach for developing composite eco-efficiency indicators: The case for US food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 299, 126931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Holmes, A.; Deurer, M.; Clothier, B.E. Eco-efficiency as a sustainability measure for kiwifruit production in New Zealand. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some Models for Estimating Technical and Scale Inefficiencies in Data Envelopment Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, M. Measuring eco-efficiency in the Finnish forest industry using public data. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R.; Petersen, H. An Introduction to Corporate Environmental Management; Greenleaf: Sheffield, UK, 2003; ISBN 9781351281447. [Google Scholar]

- Huppes, G.; Ishikawa, M. A Framework for Quantified Eco-efficiency Analysis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S. Eco-Efficiency Assessment of Zero-Emission Heavy-Duty Vehicle Concepts. Doctoral Dissertation, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Verfaillie, H.; Bidwell, R. Measuring Eco-Efficiency: A Guide to Reporting Company Performance; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; ISBN 978-2-9402-4014-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A.; Charter, M.; Ehrenfeld, J.; Huppes, G.; Lifset, R.; de Bruijn, T.; Ishikawa, M. Quantified Eco-Efficiency; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4020-5398-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine, A.; von Hauff, M. Nachhaltige Entwicklung: Grundlagen und Umsetzung; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH: München, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3486590715. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN ISO 14045:2012-10; Environmental Management—Eco-Efficiency Assessment of Product Systems—Principles, Requirements and Guidelines (ISO 14045:2012). Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- Charmondusit, K.; Phatarachaisakul, S.; Prasertpong, P. The quantitative eco-efficiency measurement for small and medium enterprise: A case study of wooden toy industry. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 16, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliuk, S. Critical appraisal of the circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 and a dashboard of quantitative system indicators for its implementation in organizations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosskopf, S.; Fare, R. Intertemporal Production Frontiers: With Dynamic DEA; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Applying a data envelopment analysis game cross-efficiency model to examining regional ecological efficiency: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R.L.; Saka, C. Environmental management accounting applications and eco-efficiency: Case studies from Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 14040:2021-02; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework (ISO 14040:2006 + Amd 1:2020). DIN: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- Álvarez Gil, M.J.; Burgos Jiménez, J.; Céspedes Lorente, J.J. An analysis of environmental management, organizational context and performance of Spanish hotels. Omega 2001, 29, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Singhal, K.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Sustainable Operations Management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2005, 14, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive Environmental Strategies: When Does it Pay to Be Green? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J. Manufacturing’s role in corporate environmental sustainability—Concerns for the new millennium. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 666–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. Modellgestütztes Service Systems Engineering: Theorie und Technik Einer Systemischen Entwicklung von Dienstleistungen; Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-3-8350-9629-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services. Eur. Manag. J. 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, J.; Bertoni, M.; Larsson, T. The Model-Driven Decision Arena: Augmented Decision-Making for Product-Service Systems Design. Systems 2020, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froböse, K. Steigert das Product-Service System Cloud-Computing Die Ökoeffizienz; CSM, Centre for Sustainability Management: Lüneburg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-942638-32-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer, L.L.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Niero, M.; Bech, N.M.; McAloone, T.C. Product/Service-Systems for a Circular Economy: The Route to Decoupling Economic Growth from Resource Consumption? J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katholieke University. Towards a Closed Loop Economy: LCE 2006, Proceedings of the 13th CIRP International Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Leuven, Belgium, 31 May–2 June 2006; Duflou, J.R., Ed.; Katholieke University: Leuven, Belgium, 2006; ISBN 905682712X. [Google Scholar]

- Glauninger, I.; Tugarin, N.; van Husen, C. Concept for a Potential Assessment of Smart Green Service Applications. Procedia CIRP 2024, 128, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauninger, I. Mit KI zur Nachhaltigkeit: Nachhaltigkeitspotenziale mithilfe Künstlicher Intelligenz leichter identi!zieren und heben. In Green Services Nachhaltige Dienstleistungen als Chance für Kleine und Mittlere Unternehmen Kompetenzzentrum Smart Services; CoPa Verlag c/o Content Partners GmbH: München, Germany, 2024; pp. 41–55. ISBN 9783982098982. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Q. 2002, 26, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Keele University and Durham University Joint Report; Keele University: Staffordshire, UK; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Briner, R.B.; Denyer, D. Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis as a Practice and Scholarship Tool. In The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Management; Rousseau, D.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 112–129. ISBN 0199763984. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran, V.; Shankar, S. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis demystified. Indian J. Rheumatol. 2015, 10, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 6th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780273750802. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Reyes, J.A. Lean and green—A systematic review of the state of the art literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.V.; Bond, A.J.; Vaz, C.R.; Borchardt, M.; Pereira, G.M.; Selig, P.M.; Varvakis, G. Critical attributes of Sustainability in Higher Education: A categorisation from literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Ojasalo, K. Service productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauninger, I.; Fehrenbach, D.; Metzger, R.; van Husen, C. Digitales Training zur Unterstützung nachhaltiger Services. In Sustainable Service Management; Bruhn, M., Hadwich, K., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024; pp. 559–584. ISBN 978-3-658-45145-5. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.H.; Foran, B.D.; Axon, C.J.; Stamp, A.V. Is the service industry really low-carbon? Energy, jobs and realistic country GHG emissions reductions. Appl. Energy 2021, 292, 116878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M.; Schiller, C.; Said, C.; Stern, E.; Glauninger, I.; Guhl, J.; Fulde, T. Green Services: Welchen Stellenwert Hat ökologische Nachhaltigkeit in Unternehmen? Study. Fraunhofer IAO: Stuttgart, Germany, 2025. 81p. Available online: https://publica.fraunhofer.de/entities/publication/f78039f6-b1ee-4b0a-a706-1de67daa56b8 (accessed on 14 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- DIN SPEC 35201:2015-04; Reference Model for the Development of Sustainable Services. DIN: Berlin, Germany, 2015.

- ISO 26000:2010; Guidance on Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Azapagic, A. Developing a framework for sustainable development indicators for the mining and minerals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 639–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasik, A.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; Kanellopoulos, A.; Claassen, G.D.H.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J. Multi-criteria decision making approaches for green supply chains: A review. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2018, 30, 366–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changwichan, K.; Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S. Eco-Efficiency Assessment of Bioplastics Production Systems and End-of-Life Options. Sustainability 2018, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Guo, Q.; Mi, L.; Wang, G.; Song, W. Spatial Distribution of Agricultural Eco-Efficiency and Agriculture High-Quality Development in China. Land 2022, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damineli, B.L.; Kemeid, F.M.; Aguiar, P.S.; John, V.M. Measuring the eco-efficiency of cement use. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellweg, S.; Doka, G.; Finnveden, G.; Hungerbühler, K. Assessing the Eco-efficiency of End-of-Pipe Technologies with the Environmental Cost Efficiency Indicator. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, R.-R. Eco-Efficiency in the Finnish and Swedish Pulp and Paper Industry; Finnish Academy of Technology: Espoo, Finland, 1998; ISBN 952-5148-50-5. [Google Scholar]

- Helminen, R.-R. Developing tangible measures for eco-efficiency: The case of the Finnish and Swedish pulp and paper industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2000, 9, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.; Catarino, J. Sustainable value—An energy efficiency indicator in wastewater treatment plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukkinen, J. From groundless universalism to grounded generalism: Improving ecological economic indicators of human–environmental interaction. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 44, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, T.; Kim, I.; Yamamoto, R. Measurement of green productivity and its improvement. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollands, N.; Lermit, J.; Patterson, M. Aggregate eco-efficiency indices for New Zealand—A principal components analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 73, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, P.G.; Mangili, P.V.; Santos, R.O.; Santos, L.S.; Prata, D.M. Economic and environmental analysis of the cumene production process using computational simulation. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2018, 130, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharel, G.P.; Charmondusit, K. Eco-efficiency evaluation of iron rod industry in Nepal. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounetas, K.E.; Polemis, M.L.; Tzeremes, N.G. Measurement of eco-efficiency and convergence: Evidence from a non-parametric frontier analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, I.C.; de Almada Garcia, P.A.; de Almeida D’Agosto, M. A data envelopment analysis approach to choose transport modes based on eco-efficiency. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, R.D.; Nunes, A.O.; Message Costa, L.B.; Silva, D.A.L. Creating value with less impact: Lean, green and eco-efficiency in a metalworking industry towards a cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, J.; Hui, E.C.; Leung, B.Y.; Li, Q. An emergy analysis-based methodology for eco-efficiency evaluation of building manufacturing. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Huang, R.; Shen, Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, J. Optimizing the recovery pathway of a net-zero energy wastewater treatment model by balancing energy recovery and eco-efficiency. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Toja, Y.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Amores, M.J.; Termes-Rifé, M.; Marín-Navarro, D.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Benchmarking wastewater treatment plants under an eco-efficiency perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, R.; Silva, C.; Costa, E. Eco-efficiency assessment in the agricultural sector: The Monte Novo irrigation perimeter, Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, E.; Komerska, A.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Wąs, A.; Sulewski, P.; Gołaś, M.; Pogodzińska, K.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Tocco, B.; et al. Are Short Food Supply Chains More Environmentally Sustainable than Long Chains? A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of the Eco-Efficiency of Food Chains in Selected EU Countries. Energies 2020, 13, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, K. Measuring eco-efficiency of wheat production in Japan: A combined application of life cycle assessment and data envelopment analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxime, D.; Marcotte, M.; Arcand, Y. Development of eco-efficiency indicators for the Canadian food and beverage industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, G.; Overwien, B. Nachhaltige Entwicklung. In Grundbegriffe Ganztagsbildung; Coelen, T., Otto, H.-U., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 299–307. ISBN 978-3-531-15367-4. [Google Scholar]

- Molinos-Senante, M.; Hernández-Sancho, F.; Mocholí-Arce, M.; Sala-Garrido, R. Economic and environmental performance of wastewater treatment plants: Potential reductions in greenhouse gases emissions. Resour. Energy Econ. 2014, 38, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, T.; Tsunemi, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yabar, H.; Yoshida, N. Eco-efficiency of Advanced Loop-closing Systems for Vehicles and Household Appliances in Hyogo Eco-town. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, V.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Marques, A.C.; Santiago, R. Assessing eco-efficiency through the DEA analysis and decoupling index in the Latin America countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, M.X.; de Medeiros, G.A.; Mancini, S.D.; Gasol, C.; Pons, J.R.; Durany, X.G. Transition towards eco-efficiency in municipal solid waste management to reduce GHG emissions: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.P.; Prata, D.M.; Santos, L.d.S.; Monteiro, L.P.C. Development of eco-efficiency comparison index through eco-indicators for industrial applications. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Tadeo, A.J.; Beltrán-Esteve, M.; Gómez-Limón, J.A. Assessing eco-efficiency with directional distance functions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 220, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintano, C.; Mazzocchi, P.; Rocca, A. Examining eco-efficiency in the port sector via non-radial data envelopment analysis and the response based procedure for detecting unit segments. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquim, F.M.; Sakamoto, H.M.; Mierzwa, J.C.; Kulay, L.; Seckler, M.M. Eco-efficiency analysis of desalination by precipitation integrated with reverse osmosis for zero liquid discharge in oil refineries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberti, M. The chip manufacturing industry: Environmental impacts and eco-efficiency analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybaczewska-Błażejowska, M.; Gierulski, W. Eco-Efficiency Evaluation of Agricultural Production in the EU-28. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, O. Eco-efficiency and industrial symbiosis—A counterfactual analysis of a mining community. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrrakou, E.; Papaefthimiou, S.; Yianoulis, P. Eco-efficiency evaluation of a smart window prototype. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 359, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.; Gomes, L.L.; de Aquino, A.C.B.; Pagliarussi, M.S. Disclosing the Consumption of Natural Resources by the Companies through the Eco-efficiency Indicators. Braz. Bus. Rev. 2006, 3, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, M.; Mehmeti, A.; Cantore, V. Impact of different water and nitrogen inputs on the eco-efficiency of durum wheat cultivation in Mediterranean environments. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, B.; Tichavska, M. Environmental cost and eco-efficiency from vessel emissions under diverse SOx regulatory frameworks: A special focus on passenger port hubs. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Caneghem, J.; Block, C.; Cramm, P.; Mortier, R.; Vandecasteele, C. Improving eco-efficiency in the steel industry: The ArcelorMittal Gent case. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Caneghem, J.; Block, C.; van Hooste, H.; Vandecasteele, C. Eco-efficiency trends of the Flemish industry: Decoupling of environmental impact from economic growth. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gerven, T.; Block, C.; Geens, J.; Cornelis, G.; Vandecasteele, C. Environmental response indicators for the industrial and energy sector in Flanders. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogtländer, J.G.; Bijma, A.; Brezet, H.C. Communicating the eco-efficiency of products and services by means of the eco-costs/value model. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Hansson, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, R. Implementing stricter environmental regulation to enhance eco-efficiency and sustainability: A case study of Shandong Province’s pulp and paper industry, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Di, J.; Chen, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, B. A Material Flow Analysis (MFA)-based potential analysis of eco-efficiency indicators of China’s cement and cement-based materials industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jin, F.; Wang, C.; Lv, C. Industrial eco-efficiency and its spatial-temporal differentiation in China. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2012, 6, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Xu, L. Eco-efficiency optimization for municipal solid waste management. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 104, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator Number | Indicator Group | Indicator | Sum of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | ENIG1 | Energy | 4 |

| E6 | ENIG2 | Water (Consumption) | 1 |

| E7 | ENIG2 | Water (Discharge) | 1 |

| E8 | ENIG3 | Raw Materials (Consumption) | 3 |

| E12 | ENIG4 | Minerals (Depletion) | 1 |

| E15 | ENIG5 | Greenhouse Gases | 3 |

| E18 | ENIG5 | Water Pollutants | 1 |

| E22 | ENIG5 | Air Pollutants | 2 |

| E23 | ENIG5 | Waste Water (Toxic) | 2 |

| E29 | ENIG6 | Soil pollution | 1 |

| E39 | ENIG6 | Emissions (Air, Water, Waste) | 1 |

| E40 | ENIG6 | Energy-Related Air Emissions | 1 |

| E43 | ENIG6 | Land (Use) | 1 |

| Indicator Number | Indicator Group | Indicator | Sum of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC2 | ECIG1 | Transport revenue | 1 |

| EC3 | ECIG1 | Turnover | 1 |

| EC5 | ECIG2 | Additional cost (with material input) | 1 |

| EC9 | ECIG2 | Total value added of products avoided cost with recycling | 1 |

| EC10 | ECIG3 | Value added | 2 |

| EC14 | ECIG4 | Amount of production | |

| EC17 | ECIG5 | Gross margin: Net sales minus costs of goods and services sold | 1 |

| EC19 | ECIG5 | Profit/Cost ratio | 2 |

| EC22 | ECIG6 | Labor Stock | 1 |

| EC23 | ECIG6 | Safety | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Glauninger, I.; Husen, C.v. Eco-Efficiency Indicators: A Literature Review and Analysis. Sustainability 2026, 18, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010075

Glauninger I, Husen Cv. Eco-Efficiency Indicators: A Literature Review and Analysis. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlauninger, Isger, and Christian van Husen. 2026. "Eco-Efficiency Indicators: A Literature Review and Analysis" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010075

APA StyleGlauninger, I., & Husen, C. v. (2026). Eco-Efficiency Indicators: A Literature Review and Analysis. Sustainability, 18(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010075