Examining the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Project Social Responsibility Performance in Post-Disaster Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

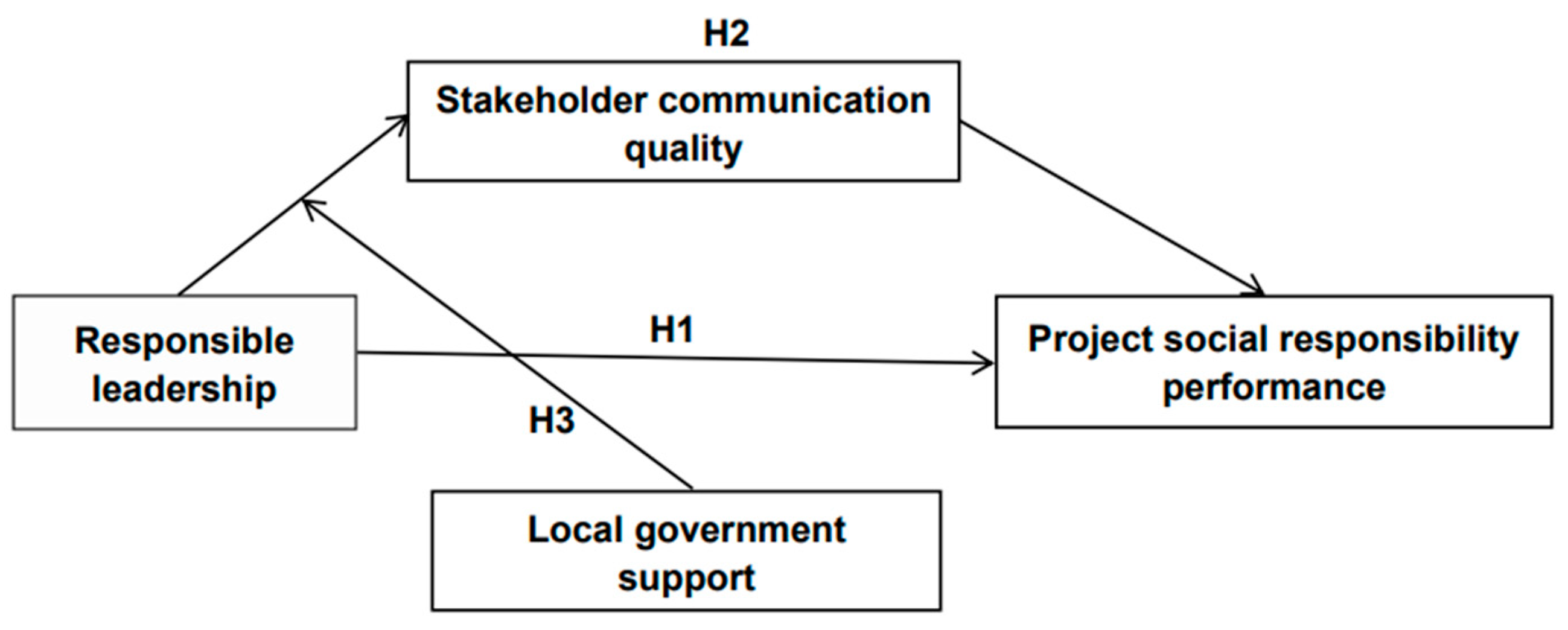

2. Research Hypothesis

2.1. Responsible Leadership and Project Social Responsibility Performance

2.2. The Mediating Role of Stakeholder Communication Quality

2.3. The Moderating Role of Local Government Support

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

3.2. Variable Measurement

4. Analysis of Findings

4.1. Model Fit Goodness-of-Fit

4.2. Reliability Testing

4.3. Common Method Bias Test

4.4. Hypothesis Testing and Analysis of Results

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Significance

5.2. Management Insights

5.3. Research Limitations and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panwar, V.; Sen, S. Fiscal repercussions of natural disasters: Stylized facts and panel data evidences from India. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2020, 21, 04020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Emergency Management. The Office of the National Disaster Prevention, Mitigation, and Relief Commission and the Ministry of Emergency Management Released the National Natural Disaster Situation in the First Half of 2024; Ministry of Emergency Management of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/yjglbgzdt/202407/t20240712_494600.shtml (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, H.; Evans, R. Build back better: A framework for sustainable recovery assessment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76, 102998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plat, S.; So, E. Speed or deliberation: A comparison of post-disaster recovery in Japan, Turkey, and Chile. Disasters 2017, 41, 696–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, P.J. Post-disaster reconstruction: A current analysis of Gujarat’s response after the 2001 earthquake. In Beyond Shelter After Disaster: Practice, Process and Possibilities; David, S., Jeni, B., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R.; Seville, E. Managing resources in disaster recovery projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2012, 19, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Seville, E.; Potangaroa, R. Resourcing for a resilient post-disaster reconstruction environment. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2010, 1, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunola, O.H. Stakeholder engagement in disaster recovery: Insights into roles and power dynamics from the Ahr Valley, Germany. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Sui, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, L.; Zeng, S. CEO narcissism, public concern, and megaproject social responsibility: Moderated mediating examination. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, J.; Shin, S. Disaster vulnerability and community resilience factors affecting post-disaster wellness: A longitudinal analysis of the Survey on the Change of Life of Disaster Victim. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shao, Y. The role of the state in China’s post-disaster reconstruction planning: Implications for resilience. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C. Development of a Scale Measuring Discursive Responsible Leadership; Pless, N.M., Maak, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuchi, K.; Johnson, L.A.; Olshansky, R.B. Securing Tohoku’s future: Planning for rebuilding in the first year following the Tohoku-oki earthquake and tsunami. Earthq. Spectra 2013, 29, S479–S499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kelemen, M.; Kiyomiya, T. The role of community leadership in disaster recovery projects: Tsunami lessons from Japan. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witton, F.; Rasheed, E.O.; Rotimi, J.O.B. Does leadership style differ between a post-disaster and non-disaster response project? A study of three major projects in New Zealand. Buildings 2019, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missonier, S.; Loufrani-Fedida, S. Stakeholder analysis and engagement in projects: From stakeholder relational perspective to stakeholder relational ontology. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1108–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H. Relational coordination: Coordinating work through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge and mutual respect. In Relational Perspectives in Organizational Studies: A Research Companion; Olympia, K., Mustafa, Ö., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R.; Seville, E. Resourcing challenges for post-disaster housing reconstruction: A comparative analysis. Build. Res. Inf. 2010, 38, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, K.; Warren, C.M. Stakeholders and their significance in post natural disaster reconstruction projects: A systematic review of the literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidian, A.; Fayazi, M. Critical factors to succeed in post-earthquake housing reconstruction in Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, D.; Wei, W. Responsible leadership and employee ethical voice: Mediating role of ethical efficacy and moderating role of moral identity. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 29516–29527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S.; Schindler, D.W.; Walker, B.W.; Roughgarden, J. Biodiversity in the functioning of ecosystems: An ecological synthesis. In Biodiveristy Loss: Economic and Ecological Issues; Perrings, C., Maler, K.G., Folke, C., Holling, C.S., Jansson, B.O., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 44–83. [Google Scholar]

- Voegtlin, C.; Frisch, C.; Walther, A.; Schwab, P. Theoretical development and empirical examination of a three-roles model of responsible leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M. Organizational inclusion and academics’ psychological contract: Can responsible leadership mediate the relationship? Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2020, 39, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Smith, L.; Violanti, J. Disaster response: Risk, vulnerability and resilience. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2000, 9, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Lam, S.S.; Peng, A.C. Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.A.O.; Wayne, S.J.; Glibkowski, B.C.; Bravo, J. The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 647–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.W.; Garavan, T.; Javed, M.; Huo, C.; Junaid, M.; Hussain, K. Responsible leadership, organizational ethical culture, strategic posture, and green innovation. Serv. Ind. J. 2023, 43, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, K.; Serrao-Neumann, S. Role of social belongingness during the post-disaster recovery. In No Poverty. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Liu, X. How CEO responsible leadership shapes corporate social responsibility and organization performance: The roles of organizational climates and CEO founder status. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 1944–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, O.D. The Notions of Disaster Risk: Conceptual framework for Integrated Management. In Information and Indicators Program for Disaster Risk Management; InterAmerican Development Bank: Manizales, Colombia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.B.; Barclay, D.W. The effects of organizational differences and trust on the effectiveness of selling partner relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T.; Stahl, G.K. Developing responsible global leaders through international service-learning programs: The Ulysses experience. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2011, 10, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Quigley, N.R. Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: Influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. Responsible leadership and employee outcomes: A systematic literature review, integration and propositions. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 13, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Stumpf, S.A.; Tymon, W.G. Responsible leadership helps retain talent in India. J. Bus. Ethics. 2011, 98, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, M.; Loosemore, M. Swift trust formation in multi-national disaster project management teams. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.; Jackson, P.R. Rethinking internal communication: A stakeholder approach. Corp. Commun. 2007, 12, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.; Littlechild, J. Building trust through communication. J. Financ. Plan. 2015, 28, 28. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/building-trust-through-communication/docview/1730778898/se-2 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Villena Manzanares, F.; García-Segura, T.; Pellicer, E. Effective communication in BIM as a driver of CSR under the happiness management approach. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmers-Sommer, T.M. The effect of communication quality and quantity indicators on intimacy and relational satisfaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 21, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontainha, T.C.; Leiras, A.; Bandeira, R.; Scavarda, L.F. Stakeholder satisfaction in complex relationships during the disaster response: A structured review and a case study perspective. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 33, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P.; Falkenberg, L. The role of collaboration in achieving corporate social responsibility objectives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R.; Seville, E. Resourcing for post-disaster reconstruction: A comparative study of Indonesia and China. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2012, 21, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Peng, B. Dynamic Mechanisms of R&D Innovation in Chinese Multinational Corporations: The Impact of Government Support, Market Competition and Entrepreneurial Spirit. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Zheng, T.; Gao, F.; Zhao, H. Stimulating Start-up Investment Through Government-Sponsored Venture Capital: Theory and Chinese Evidence. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2024, 37, 2021–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songling, Y.; Ishtiaq, M.; Anwar, M.; Ahmed, H. The role of government support in sustainable competitive position and firm performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miotto, G.; Del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A. Reputation and legitimacy: Key factors for Higher Education Institutions’ sustained competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Weiss, H.M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Hulin, C.L. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayat, M.; Ullah, A.; Kang, C. The unsolicited proposal and performance of private participation infrastructure projects in developing countries. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022, 22, 901–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.; Chan, A.P. Key performance indicators for measuring construction success. Benchmarking 2004, 11, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society–a relational perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 66, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Interviewee | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage% | |

| Genders | ||

| Male | 90 | 56.6 |

| Female | 69 | 43.4 |

| Age | ||

| Under 31 years | 52 | 32.7 |

| 31–35 years | 28 | 17.6 |

| 36–40 years | 28 | 17.6 |

| 41–45 years | 26 | 16.4 |

| 46–50 years | 18 | 11.3 |

| Above 50 years | 7 | 4.4 |

| Educational level | ||

| Junior high school and below | 7 | 4.4 |

| High School/Junior College | 22 | 13.8 |

| University College | 35 | 22.0 |

| Undergraduate | 75 | 47.2 |

| Postgraduate and above | 20 | 12.6 |

| Position | ||

| Grassroots Management | 108 | 67.9 |

| Middle Management | 38 | 23.9 |

| Senior Management | 13 | 8.2 |

| Working experience | ||

| 1–5 years | 52 | 32.7 |

| 6–10 years | 38 | 23.9 |

| 11–15 years | 30 | 18.9 |

| 16–20 years | 22 | 13.8 |

| Above 20 years | 17 | 10.7 |

| Project scale | ||

| Less than 5 million yuan | 43 | 27.0 |

| 5–10 million yuan | 13 | 8.2 |

| 10–20 million yuan | 24 | 15.1 |

| 20–30 million yuan | 9 | 5.7 |

| 30–40 million yuan | 5 | 3.1 |

| Above 40 million yuan | 65 | 40.9 |

| Project duration | ||

| Less than 6 months | 49 | 30.8 |

| 6 months–1 year | 29 | 18.2 |

| 1–2 years | 34 | 21.4 |

| 2–3 years | 25 | 15.7 |

| More than 3 years | 22 | 13.8 |

| Project Type | ||

| Urban and rural housing construction category | 52 | 32.7 |

| Infrastructure and public service facilities | 78 | 49.1 |

| Geological disaster prevention and control | 13 | 8.2 |

| Ecological environment restoration and protection | 6 | 3.8 |

| Scenic restoration and industrial development | 2 | 1.3 |

| Others | 8 | 5.0 |

| LGS | PSPR | RL | SCQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGS | ||||

| PSPR | 0.675 | |||

| RL | 0.214 | 0.355 | ||

| SCQ | 0.696 | 0.570 | 0.426 | |

| LGS × RL | 0.150 | 0.078 | 0.388 | 0.389 |

| R2 | 0.336 | 0.538 | ||

| R2 adjusted | 0.349 | 0.523 | ||

| ∆R2 | 0.013 | 0.015 |

| Correlation Matrix | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Variables | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | LGS | CSRP | RL | SCQ |

| LGS | 0.907 | 0.909 | 0.781 | 0.884 | — | — | — |

| CSRP | 0.949 | 0.952 | 0.552 | 0.633 | 0.743 | — | — |

| RL | 0.914 | 0.917 | 0.745 | 0.197 | 0.328 | 0.863 | — |

| SCQ | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.805 | 0.645 | 0.569 | 0.396 | 0.897 |

| Measurement Item | LGS | CSRP | RL | SCQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSRP-Ec1 | 0.424 | 0.750 | 0.233 | 0.351 |

| CSRP-Ec2 | 0.473 | 0.665 | 0.165 | 0.485 |

| CSRP-Ec3 | 0.421 | 0.707 | 0.259 | 0.432 |

| CSRP-Ec4 | 0.498 | 0.696 | 0.187 | 0.510 |

| CSRP-Ec5 | 0.492 | 0.765 | 0.288 | 0.438 |

| CSRP-Et1 | 0.575 | 0.819 | 0.255 | 0.421 |

| CSRP-Et2 | 0.537 | 0.721 | 0.234 | 0.329 |

| CSRP-Et4 | 0.559 | 0.789 | 0.248 | 0.377 |

| CSRP-Le1 | 0.513 | 0.779 | 0.291 | 0.491 |

| CSRP-Le2 | 0.551 | 0.813 | 0.198 | 0.492 |

| CSRP-Le3 | 0.510 | 0.775 | 0.366 | 0.488 |

| CSRP-Le4 | 0.540 | 0.791 | 0.178 | 0.477 |

| CSRP-Po1 | 0.310 | 0.682 | 0.222 | 0.305 |

| CSRP-Po2 | 0.361 | 0.707 | 0.269 | 0.346 |

| CSRP-Po3 | 0.390 | 0.742 | 0.208 | 0.385 |

| CSRP-Po4 | 0.372 | 0.712 | 0.266 | 0.331 |

| CSRP-Po5 | 0.385 | 0.697 | 0.276 | 0.395 |

| LGS1 | 0.882 | 0.544 | 0.196 | 0.593 |

| LGS2 | 0.888 | 0.582 | 0.225 | 0.593 |

| LGS3 | 0.891 | 0.572 | 0.147 | 0.572 |

| LGS4 | 0.875 | 0.537 | 0.121 | 0.517 |

| RL1 | 0.144 | 0.270 | 0.856 | 0.328 |

| RL2 | 0.163 | 0.283 | 0.883 | 0.350 |

| RL3 | 0.188 | 0.269 | 0.845 | 0.316 |

| RL4 | 0.192 | 0.306 | 0.892 | 0.381 |

| RL5 | 0.162 | 0.286 | 0.837 | 0.326 |

| SCQ1 | 0.566 | 0.506 | 0.362 | 0.882 |

| SCQ2 | 0.520 | 0.493 | 0.386 | 0.860 |

| SCQ3 | 0.628 | 0.505 | 0.352 | 0.921 |

| SCQ4 | 0.605 | 0.559 | 0.344 | 0.926 |

| SCQ5 | 0.572 | 0.487 | 0.333 | 0.895 |

| Path | Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | F-Square | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RL→PSRP | 0.231 | 0.101 | 2.272 | 0.023 | 0.024 | Supported |

| RL→SCQ | 0.201 | 0.095 | 2.121 | 0.034 | 0.073 | Supported |

| SCQ→PSRP | 0.498 | 0.123 | 4.040 | 0.000 | 0.318 | Supported |

| LGS × RL→SCQ | 0.175 | 0.084 | 2.090 | 0.037 | 0.082 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, J. Examining the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Project Social Responsibility Performance in Post-Disaster Reconstruction. Sustainability 2026, 18, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010059

Yu X, Wang J, Yu J. Examining the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Project Social Responsibility Performance in Post-Disaster Reconstruction. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xuan, Jinmei Wang, and Jiakun Yu. 2026. "Examining the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Project Social Responsibility Performance in Post-Disaster Reconstruction" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010059

APA StyleYu, X., Wang, J., & Yu, J. (2026). Examining the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Project Social Responsibility Performance in Post-Disaster Reconstruction. Sustainability, 18(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010059