Carbon Footprint Analysis of Alcohol Production in a Distillery in Three Greenhouse Gas Emission Scopes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Climate neutrality: Aiming for net-zero emissions by 2050, with intermediate targets such as reducing emissions by at least 55% by 2030.

- Energy: Greening the energy system by increasing the share of renewable energy sources, improving energy efficiency, and creating an integrated energy market.

- Circular economy: Including better waste management, recycling, and reducing material losses.

- Nature conservation: Protecting biodiversity, restoring ecosystems (e.g., rivers, soils, habitats), reducing pesticide use, and planting 3 billion trees in the EU by 2030.

- Agriculture: Introduction of a “farm to fork” strategy, which aims to shorten supply chains, increase the share of organic farming to 25% of agricultural land by 2030, and reduce nutrient losses by at least 50%.

- Pollution reduction: Reducing air, water, and soil pollution, including through the development of an action plan to eliminate pollution.

- Innovation and industry: Support for clean technologies, simplification of regulations, access to financing, and development of skills in the industrial sector.

- -

- H1: Replacing conventional energy (coal, natural gas) with renewable energy sources (RES) in distillation processes can reduce the carbon footprint of spirit production.

- -

- H2: The production of high-percentage alcohol from local raw materials generates a lower carbon footprint than from imported raw materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Object

2.2. Methodology

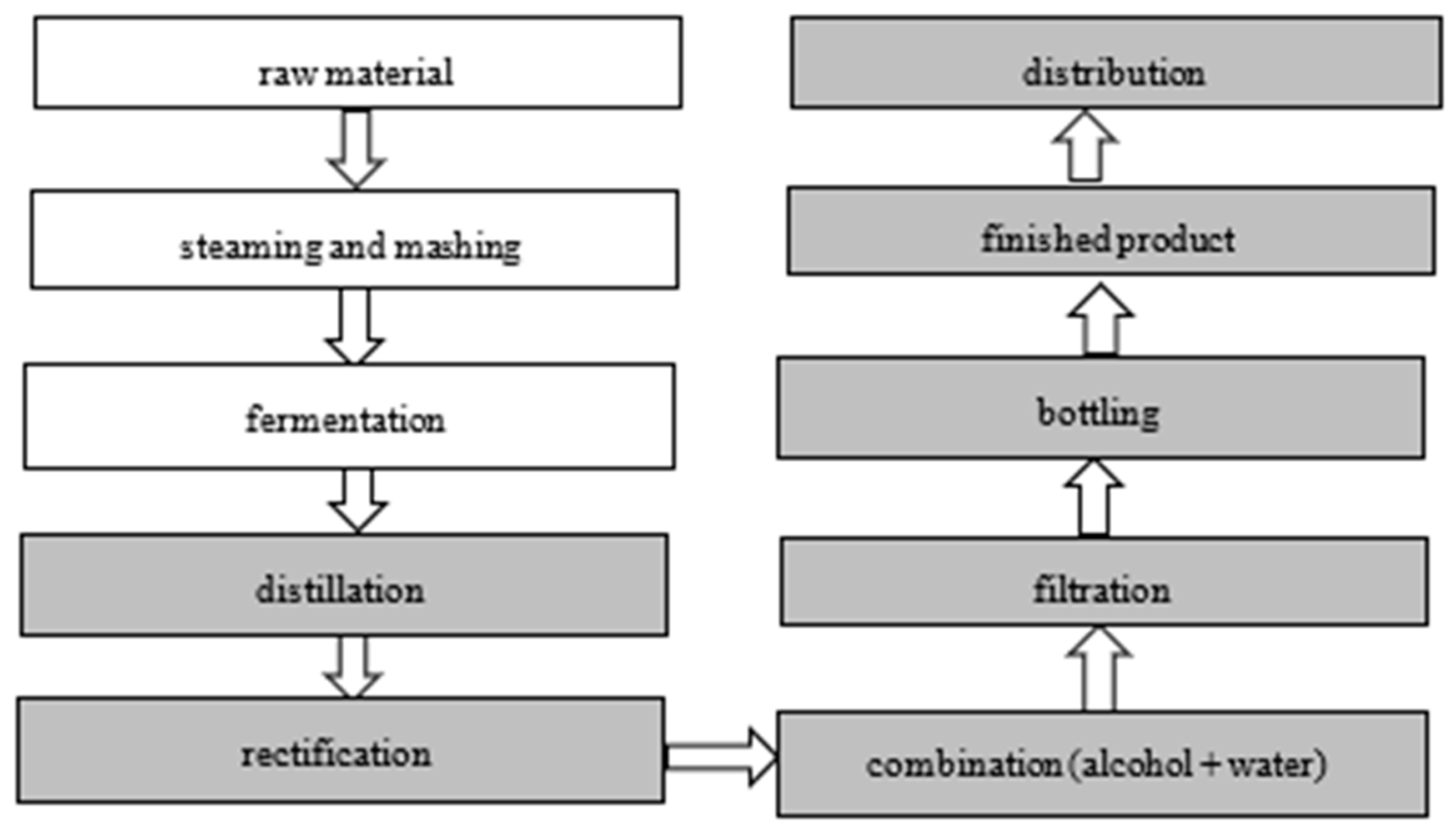

- Rectification—in rectification columns, impurities and non-volatile fractions are separated, which requires large amounts of steam and cooling. Emissions at this stage result from the combustion of biomass and gas (Scope 1) and from the consumption of electricity to drive pumps, compressors, and automation systems (Scope 2).

- Blending and dilution—rectified alcohol is diluted with osmotic water to the appropriate concentration. The process requires small amounts of electricity but generates indirect emissions from the operation of the equipment.

- Filtration and clarification—involves removing fine particles and improving the clarity of the vodka using cellulose filters and activated carbon. Emissions result mainly from the electricity needed to pump liquids and operate filters.

- Bottling and packaging—the process involves filling bottles, labeling, capping, wrapping, and palletizing. Emissions come from bottling machines, wrapping machines, and internal transport (electric and combustion engine trucks).

- Transport and distribution—this includes the transport of raw materials, packaging, and finished products. These emissions are classified as Scope 3 and can account for 20 to 40% of the total carbon footprint, depending on the distance and type of transport.

- Scope 1—direct emissions from production processes and fuel combustion on site,

- Scope 2—indirect emissions related to the generation of electricity, steam, and heat supplied from outside sources,

- Scope 3—other indirect emissions including transportation, raw materials, waste, packaging, and distribution.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Production Volume

3.2. Review of Carbon Footprint of Spirits Production Worldwide

3.3. GHG Emissions Analysis

3.4. Analysis of Potential GHG Emission Reduction Strategies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szafranowicz, M. Marketing communication of producers of high-proof alcoholic beverages in Poland. Mark. Mark. 2019, 5, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://zppps.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Branza-spirytusowa-i-jej-znaczenie-dla-polskiej-gospodarki-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. In A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age COM/2023/62; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Dixon, K.A.; Michelsen, M.K.; Carpenter, C.L. Modern Diets and the Health of Our Planet: An Investigation into the Environmental Impacts of Food Choices. Nutrients 2023, 15, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biradar, A.; Diwase, S.; Dixit, P.; Sontakke, T.; Nalage, D. Sustainability in Alcohol Production: An Overview of Green Initiatives and their Impact on the Industry. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Tech. 2024, 9, 2478–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Grilo, M.M.d.S.; Abrahao, R. Comparison of greenhouse gas emissions relative to two frying processes for homemade potato chips. Sustainability 2018, 37, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, D.d.P.; Carvalho, M.; Abrahão, R. Greenhouse gas accounting for the energy transition in a brewery. Sustainability 2020, 40, e13563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Diniz, D.d.P.; Carvalho, M. Environmental Repercussions of Craft Beer Production in Northeast Brazil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlisah, Z.N.; Ong, H.C.; Lee, H.V.; Tan, Y.H. Environmental impacts of biomass energy: A life cycle assessment perspective for circular economy. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Polish Government Regulation. Act of May 25, 2012 on the Production of Spirit Drinks and on the Registration and Protection of Geographical Indications of Spirit Drinks (Dz.U. 2012, poz. 815); The Polish Government: Warsaw, Poland, 2012.

- Regulation (EU) No. 2019/ 787 of 17 April 2019 on the Definition, Description, Presentation, and Labeling of Spirit Drinks. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/787/oj/eng (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- ISO 14001; Environmental Management Systems. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Atmaca, A. Chapter Twenty-Two-Understanding Carbon Footprint: Impact, Assessment, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Advances and Technology Development in Greenhouse Gases: Emission, Capture and Conversion; Rahimpour, M.R., Makarem, M.A., Meshksar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHG Protocol. 2022. GHG Protocol. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/guidance-0 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- ISO 14067:2018; Environmental Management–Carbon Foodprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Wróbel-Jędrzejewska, M.; Klepacka, A.M.; Włodarczyk, E.; Przybysz, Ł. Carbon Footprint of Milk Processing-Case Study of Polish Dairy. Agriculture 2025, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel-Jędrzejewska, M.; Włodarczyk, E.; Przybysz, Ł. Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions of a Mill According to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management–Life Cycle Assessment–Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- DEFRA. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2022 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- DEFRA. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2023 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- DEFRA. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2024 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- KOBiZE. CO2, SO2, NOx, CO, and Total Dust Emission Factors for Electricity Based on Information Contained in the National Database on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Other Substances for 2022; PKO Bank Polski Spółka Akcyjna: Warsaw, Poland, 2023.

- KOBiZE. CO2, SO2, NOx, CO, and Total Dust Emission Factors for Electricity Based on Information Contained in the National Database on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Other Substances for 2023; PKO Bank Polski Spółka Akcyjna: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- KOBiZE. CO2, SO2, NOx, CO, and Total Dust Emission Factors for Electricity Based on Information Contained in the National Database on Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Other Substances for 2024; PKO Bank Polski Spółka Akcyjna: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.; Delgado, D. Potential of photovoltaic solar energy to reduce the carbon footprint of the Brazilian electricity matrix. LALCA Rev. Lat.-Am. Em Aval. Do Ciclo Vida 2017, 1, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Roque, Y.B.; Diaz, P.R.; Cespedes, A.A.L.; Santos, J.J.C.S.; Barone, M.A.; Silva, J.A.M.d. Allocation in multiproduct energy systems: Review and method proposals. LALCA Rev. Lat.-Am. Em Aval. Do Ciclo Vida 2020, 4, e44660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14064:2018; Greenhouse Gases. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Becker, S.; Bouzdine-Chameeva, T.; Jaegler, A. The carbon neutrality principle: A case study in the French spirits sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxe, H. LCA-Based Comparison of the Climate Footprint of Beer vs. Wine & Spiritus; Report No. 207; Fødevareøkonomisk Institut, Københavns Universitet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Research on the Carbon Footprint of Spirits Beverage Industry Environmental Roundtable, 2012. Available online: https://www.bieroundtable.com/wp-content/uploads/49d7a0_7643fd3fae5d4daf939cd5373389e4e0.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Leivas, R.; Laso, J.; Abejón, R.; Margallo, M.; Aldaco, R. Environmental assessment of food and beverage under a NEXUS Water-Energy-Climate approach: Application to the spirit drinks. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, A.S.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Flor-Montalvo, F.J.; Martínez-Cámara, E.; Blanco, J. Sustainability in Tequila Production: A Life Cycle Assessment. Sust. Dev. 2025, 3, 6797–6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-Solórzano, J.M.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Macías, E.J.; Cámara, E.M.; Fernández, J.B. Life Cycle Analysis of Sotol Production in Mexico. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 769478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, O.; Jonsson, D.; Hillman, K. Life cycle assessment of Swedish single malt whisky. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechener, G.; Johnson, A.; Hann, S.; Hilton, M. InchDairnie Distillery Carbon Footprint; InchDairnie: Glenrothes, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stock Spirits Group Sustainability Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.stockspirits.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Sustainability_Report_fy_2022.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Altia, Life Cycle Assesment of Koskenkorva Vodka, 2019. Available online: https://mb.cision.com/Public/3171/2949315/bc0b0abfc55b1a31.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Bryszewska, M.A.; Staszków, R.; Ściubak, Ł.; Domański, J.; Dziugan, P. Renewable Energy Sources and Improved Energy Management as a Path to Energy Transformation: A Case Study of a Vodka Distillery in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Energy Carriers | Value of the Indicator in a Given Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Source | |

| Heating oil [L] | 2.54 kg CO2eq/L | 2.54 kg CO2eq/L | 2.54 kg CO2eq/L | [21,22,23] |

| Diesel fuel [L] | 2.7 kg CO2eq/L | 2.66 kg CO2eq/L | 2.66 kg CO2eq/L | |

| Gasoline [L] | 2.34 kg CO2eq/L | 2.35 kg CO2eq/L | 2.35 kg CO2eq/L | |

| LPG [L] | 1.56 kg CO2eq/L | 1.56 kg CO2eq/L | 1.56 kg CO2eq/L | |

| LPG [kg] | 2.94 kg CO2eq/kg | 2.94 kg CO2eq/kg | 2.94 kg CO2eq/kg | |

| Natural gas [kWh] | 0.2 kg CO2eq/kWh | 0.2 kg CO2eq/kWh | 0.2 kg CO2eq/kWh | |

| Natural gas [m3] | 2.02 kg CO2eq/m3 | 2.04 kg CO2eq/m3 | 2.05 kg CO2eq/m3 | |

| Biomass [kg] | 0.0398 kg CO2eq/kg | 0.0406 kg CO2eq/kg | 0.0428 kg CO2eq/kg | |

| Biomass density (wood chips) [m3] | 300 kg CO2eq/m3 | 300 kg CO2eq/m3 | 300 kg CO2eq/m3 | |

| Electricity [kWh] | 0.685 kg CO2eq/kWh | 0.597 kg CO2eq/kWh | 0.597 kg CO2eq/kWh | [24,25,26] |

| Type of Spirit | Year | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | ||

| Spirit—produced by rectifying raw spirit [L] | 2024 | - | 300,146 | 727,528 | 579,267 | - | - | - | - | - | 473,824 | 704,729 | 352,428 |

| 2023 | 358,824 | 640,469 | 773,349 | 643,012 | - | - | - | - | 71,552 | 756,275 | 786,529 | 169,188 | |

| 2022 | - | 290,295 | 785,487 | 745,082 | 739,569 | 197,957 | - | - | 141,299 | 784,899 | 696,319 | 344,845 | |

| Raw organic spirit [L] | 2024 | 115,536 | 516,277 | 573,893 | 573,923 | 483,886 | 55,143 | - | - | - | 255,588 | 401,198 | 345,089 |

| 2023 | 137,394 | - | 80,130 | 493,607 | 511,736 | 143,903 | - | - | - | 401,297 | 489,875 | 287,099 | |

| 2022 | 28,235 | - | - | - | 108,769 | 158,917 | - | - | 87,228 | 139,021 | 113,357 | 251,035 | |

| Type of Spirit | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Spirit—produced by rectifying raw spirit [L] | 4,725,752 | 4,199,198 | 3,137,922 |

| Raw organic spirit [L] | 886,562 | 2,545,041 | 3,320,533 |

| Product | Research Characteristics | Conclusions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognac |

|

| [30] |

| Vodka, Spirits |

|

| [31] |

| Whiskey |

|

| [32] |

| Gin |

|

| [33] |

| Tequila |

|

| [34] |

| Sotol |

|

| [35] |

| Whiskey |

|

| [36] |

| Whiskey |

|

| [37] |

| Group | Sub-Group | Year | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||

| Fuel—vehicles | Diesel fuel—fire pumps [L] | 2024 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| 2023 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 | ||

| 2022 | 124 | 202 | 149 | 212 | 262 | 120 | 124 | 124 | 124 | 124 | 124 | 295 | ||

| Diesel fuel—truck [L] | 2024 | 148 | 167 | 0 | 15 | 135 | 15 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2023 | 78 | 495 | 244 | 80 | 0 | 105 | 91 | 0 | 117 | 0 | 333 | 0 | ||

| 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| LPG—forklift trucks [kg] | 2024 | 836 | 1034 | 671 | 748 | 814 | 484 | 748 | 517 | 726 | 572 | 704 | 946 | |

| 2023 | 924 | 1100 | 1122 | 1089 | 1276 | 990 | 671 | 440 | 561 | 693 | 572 | 583 | ||

| 2022 | 1287 | 1100 | 1111 | 1023 | 1210 | 935 | 924 | 1067 | 924 | 1078 | 1232 | 1045 | ||

| Gasoline—passenger cars [L] | 2024 | 1077 | 1162 | 1247 | 1316 | 1345 | 1299 | 1452 | 1310 | 1050 | 1540 | 1414 | 1340 | |

| 2023 | 1531 | 1006 | 1511 | 1546 | 1480 | 1626 | 1047 | 1387 | 1325 | 1055 | 1330 | 887 | ||

| 2022 | 1153 | 1082 | 2883 | 1410 | 1374 | 1221 | 875 | 1468 | 1418 | 1275 | 1399 | 1493 | ||

| Fuel—energy purposes | Natural gas—boiler room [kWh] | 2024 | 97,981 | 33,661 | 22,575 | 577 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3455 | 31,250 | 27,593 | 7445 |

| 2023 | 12,032 | 33,686 | 61,134 | 48,110 | 16,765 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7658 | 29,201 | 59,165 | 3385 | ||

| 2022 | 45 | 83,132 | 9034 | 12,201 | 24,956 | 2753 | 0 | 0 | 11,028 | 17,342 | 61,802 | 91,990 | ||

| Biomass [m3] wood chips | 2024 | 701 | 2125 | 3216 | 2579 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3043 | 2956 | 2074 | |

| 2023 | 2632 | 3487 | 3549 | 2416 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1116 | 3484 | 3500 | 1530 | ||

| 2022 | 1187 | 1950 | 3765 | 3124 | 3028 | 692 | 0 | 0 | 1284 | 3305 | 3685 | 1617 | ||

| Electricity | Purchased electricity [kWh] | 2024 | 95,888 | 105,912 | 86,394 | 46,574 | 33,689 | 38,822 | 52,195 | 37,594 | 43,686 | 68,280 | 57,040 | 114,813 |

| 2023 | 84,699 | 73,280 | 101,017 | 70,369 | 72,278 | 67,908 | 57,893 | 38,189 | 33,734 | 27,921 | 41,366 | 79,556 | ||

| 2022 | 108,244 | 99,699 | 132,178 | 144,790 | 63,559 | 66,133 | 69,683 | 77,852 | 55,463 | 41,841 | 70,978 | 97,682 | ||

| Electricity generated from biomass (generator) [kWh] | 2024 | 0 | 5459 | 47,770 | 63,127 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53,983 | 100,748 | 13,098 | |

| 2023 | 66,587 | 91,249 | 72,705 | 62,991 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29,219 | 112,652 | 102,816 | 31,324 | ||

| 2022 | 0 | 33,700 | 25,245 | 0 | 84,469 | 23,495 | 0 | 0 | 36,445 | 107,229 | 94,362 | 31,951 | ||

| Electricity generated by photovoltaics [kWh] | 2024 | 5860 | 9859 | 22,523 | 31,188 | 51,631 | 44,006 | 44,105 | 37,525 | 32,656 | 20,096 | 7463 | 3892 | |

| 2023 | 0 | 0 | 3987 | 10,570 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33,921 | 33,020 | 15,251 | 7428 | 2314 | ||

| 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Emission [kg CO2eq] | Month | Sum | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| Diesel | 2024 | 1032 | 1083 | 639 | 678 | 998 | 678 | 1011 | 639 | 639 | 639 | 639 | 639 | 9311 |

| 2023 | 846 | 1955 | 1287 | 851 | 638 | 918 | 880 | 638 | 950 | 638 | 1524 | 638 | 11,765 | |

| 2022 | 336 | 546 | 403 | 573 | 708 | 324 | 336 | 336 | 336 | 336 | 336 | 797 | 5367 | |

| LPG | 2024 | 2458 | 3040 | 1973 | 2199 | 2393 | 1423 | 2199 | 1520 | 2134 | 1682 | 2070 | 2781 | 25,872 |

| 2023 | 2717 | 3234 | 3299 | 3202 | 3751 | 2911 | 1973 | 1294 | 1649 | 2037 | 1682 | 1714 | 29,462 | |

| 2022 | 3784 | 3234 | 3266 | 3008 | 3557 | 2749 | 2717 | 3137 | 2717 | 3169 | 3622 | 3072 | 38,032 | |

| Gasoline | 2024 | 2531 | 2731 | 2930 | 3093 | 3161 | 3053 | 3412 | 3079 | 2468 | 3619 | 3323 | 3149 | 36,547 |

| 2023 | 3598 | 2364 | 3551 | 3633 | 3478 | 3821 | 2460 | 3259 | 3114 | 2479 | 3126 | 2084 | 36,968 | |

| 2022 | 2698 | 2532 | 6746 | 3299 | 3215 | 2857 | 2048 | 3435 | 3318 | 2984 | 3274 | 3494 | 39,899 | |

| Natural gas | 2024 | 19,596 | 6732 | 4515 | 115 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 691 | 6250 | 5519 | 1489 | 44,907 |

| 2023 | 2406 | 6737 | 12,227 | 9622 | 3353 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1532 | 5840 | 11,833 | 677 | 54,227 | |

| 2022 | 9 | 16,626 | 1807 | 2440 | 4991 | 551 | 0 | 0 | 2206 | 3468 | 12,360 | 18,398 | 62,857 | |

| Electricity | 2024 | 60,744 | 72,374 | 93,542 | 84,111 | 50,936 | 49,448 | 57,491 | 44,846 | 45,576 | 84,988 | 98,655 | 78,686 | 821,398 |

| 2023 | 90,318 | 98,224 | 106,092 | 85,926 | 43,150 | 40,541 | 34,562 | 43,050 | 57,296 | 93,027 | 90,511 | 67,577 | 850,274 | |

| 2022 | 74,147 | 91,378 | 107,835 | 99,181 | 101,399 | 61,395 | 47,733 | 53,329 | 62,957 | 102,113 | 113,258 | 88,799 | 1,003,524 | |

| SUM | 2024 | 86,360 | 85,960 | 103,599 | 90,196 | 57,488 | 54,602 | 64,113 | 50,083 | 51,508 | 97,178 | 110,205 | 86,744 | 938,035 |

| 2023 | 99,884 | 112,514 | 126,456 | 103,234 | 54,371 | 48,190 | 39,876 | 48,241 | 64,540 | 104,022 | 108,676 | 72,691 | 982,696 | |

| 2022 | 80,974 | 114,317 | 120,057 | 108,501 | 113,871 | 67,876 | 52,833 | 60,237 | 71,533 | 112,070 | 132,850 | 114,559 | 1,149,678 | |

| Emissions from Glass [kg CO2eq] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December |

| 2024 | 662,842 | 670,109 | 696,925 | 755,600 | 798,134 | 914,829 | 926,194 | 524,277 | 781,931 | 800,893 | 956,928 | 765,226 |

| 2023 | 935,091 | 1,052,292 | 1,426,943 | 969,205 | 1,433,400 | 1,213,868 | 360,490 | 549,635 | 410,971 | 678,392 | 626,907 | 590,658 |

| 2022 | 94,189 | 118,320 | 137,544 | 81,923 | 135,590 | 109,736 | 126,374 | 103,785 | 89,870 | 126,517 | 122,694 | 101,297 |

| Share in Emission [%] | Month | Sum | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| Diesel | 2024 | 1.19 | 1.26 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 1.74 | 1.24 | 1.58 | 1.27 | 1.24 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 1.19 |

| 2023 | 0.85 | 1.74 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 1.90 | 2.21 | 1.32 | 1.47 | 0.61 | 1.40 | 0.88 | 0.85 | |

| 2022 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.42 | |

| LPG | 2024 | 2.85 | 3.54 | 1.90 | 2.44 | 4.16 | 2.61 | 3.43 | 3.03 | 4.14 | 1.73 | 1.88 | 3.21 | 2.85 |

| 2023 | 2.72 | 2.87 | 2.61 | 3.10 | 6.90 | 6.04 | 4.95 | 2.68 | 2.56 | 1.96 | 1.55 | 2.36 | 2.72 | |

| 2022 | 4.67 | 2.83 | 2.72 | 2.77 | 3.12 | 4.05 | 5.14 | 5.21 | 3.80 | 2.83 | 2.73 | 2.68 | 4.67 | |

| Gasoline | 2024 | 2.93 | 3.18 | 2.83 | 3.43 | 5.50 | 5.59 | 5.32 | 6.15 | 4.79 | 3.72 | 3.02 | 3.63 | 2.93 |

| 2023 | 3.60 | 2.10 | 2.81 | 3.52 | 6.40 | 7.93 | 6.17 | 6.76 | 4.82 | 2.38 | 2.88 | 2.87 | 3.60 | |

| 2022 | 3.33 | 2.21 | 5.62 | 3.04 | 2.82 | 4.21 | 3.88 | 5.70 | 4.64 | 2.66 | 2.46 | 3.05 | 3.33 | |

| Natural gas | 2024 | 22.69 | 7.83 | 4.36 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.34 | 6.43 | 5.01 | 1.72 | 22.69 |

| 2023 | 2.41 | 5.99 | 9.67 | 9.32 | 6.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.37 | 5.61 | 10.89 | 0.93 | 2.41 | |

| 2022 | 0.01 | 14.54 | 1.50 | 2.25 | 4.38 | 0.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.08 | 3.09 | 9.30 | 16.06 | 0.01 | |

| Electricity | 2024 | 70.34 | 84.20 | 90.29 | 93.25 | 88.60 | 90.56 | 89.67 | 89.54 | 88.48 | 87.46 | 89.52 | 90.71 | 70.34 |

| 2023 | 90.42 | 87.30 | 83.90 | 83.23 | 79.36 | 84.13 | 86.67 | 89.24 | 88.78 | 89.43 | 83.29 | 92.96 | 90.42 | |

| 2022 | 91.57 | 79.93 | 89.82 | 91.41 | 89.05 | 90.45 | 90.35 | 88.53 | 88.01 | 91.12 | 85.25 | 77.51 | 91.57 | |

| Month | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | ||||||||||||

| CF [kg CO2eq/L] | 2.87 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| 2023 | ||||||||||||

| CF [kg CO2eq/L] | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| 2024 | ||||||||||||

| CF [kg CO2eq/L] | 0.72 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Year | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average CF [kg CO2eq/L] | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| Month | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | ||||||||||||

| Produced WNS * [L] | 587,326 | 603,987 | 602,250 | 665,728 | 708,480 | 806,522 | 822,114 | 471,198 | 714,726 | 733,982 | 946,951 | 719,789 |

| GHG emission [kg CO2eq] | 86,360 | 85,960 | 103,599 | 90,196 | 57,488 | 54,602 | 64,113 | 50,083 | 51,508 | 97,178 | 110,205 | 86,744 |

| CFWNS [kg CO2eq/L] | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| 2023 | ||||||||||||

| Produced WNS * [L] | 819,003 | 929,100 | 1,267,267 | 869,500 | 1,249,269 | 1,092,472 | 307,881 | 482,089 | 350,650 | 585,549 | 553,935 | 519,682 |

| GHG emission [kg CO2eq] | 99,884 | 112,514 | 126,456 | 103,234 | 54,371 | 48,190 | 39,876 | 48,241 | 64,540 | 104,022 | 108,676 | 72,691 |

| CFWNS [kg CO2eq/L] | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.14 |

| 2022 | ||||||||||||

| Produced WNS * [L] | 87,245 | 110,564 | 128,976 | 72,857 | 126,875 | 100,704 | 118,688 | 95,015 | 80,421 | 119,968 | 114,410 | 94,326 |

| GHG emission [kg CO2eq] | 80,974 | 114,317 | 120,057 | 108,501 | 113,871 | 67,876 | 52,833 | 60,237 | 71,533 | 112,070 | 132,850 | 114,559 |

| CFWNS [kg CO2eq/L] | 0.93 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 1.49 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 1.16 | 1.21 |

| Product | CF for Spirit Products | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cognac | 0.9 ton CO2eq/hL | [30] |

| Vodka, Spirits | 0.981 kg CO2eq/L vodka 0.8 kg–2.3 kg CO2eq/L spirit the most representative emission caused by the full life cycle of a 1 L spirit drink was 6 kg CO2eq | [31] |

| Whiskey | 2745 g CO2eq/0.75 L whiskey (Column Distillation) 2970 g CO2eq/0.75 L whiskey (Pot Distillation) | [32] |

| Gin | 0.877 kg CO2eq/L gin | [33] |

| Tequila | a 700 mL bottle of tequila aged for 6 months generates: 2.27 kg CO2eq/0.7 L tequila | [34] |

| Sotol | 5.92 kg CO2eq/0.75 L sotol | [35] |

| Whiskey | 2.97 kg CO2eq/0.7 L whiskey 2.52 kg CO2eq/0.5 L whiskey | [36] |

| Whiskey | 2.39 kg CO2eq/L whiskey | [11] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wróbel-Jędrzejewska, M.; Przybysz, Ł.; Włodarczyk, E.; Owczarek, F.; Ściubak, Ł. Carbon Footprint Analysis of Alcohol Production in a Distillery in Three Greenhouse Gas Emission Scopes. Sustainability 2026, 18, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010057

Wróbel-Jędrzejewska M, Przybysz Ł, Włodarczyk E, Owczarek F, Ściubak Ł. Carbon Footprint Analysis of Alcohol Production in a Distillery in Three Greenhouse Gas Emission Scopes. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleWróbel-Jędrzejewska, Magdalena, Łukasz Przybysz, Ewelina Włodarczyk, Filip Owczarek, and Łukasz Ściubak. 2026. "Carbon Footprint Analysis of Alcohol Production in a Distillery in Three Greenhouse Gas Emission Scopes" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010057

APA StyleWróbel-Jędrzejewska, M., Przybysz, Ł., Włodarczyk, E., Owczarek, F., & Ściubak, Ł. (2026). Carbon Footprint Analysis of Alcohol Production in a Distillery in Three Greenhouse Gas Emission Scopes. Sustainability, 18(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010057