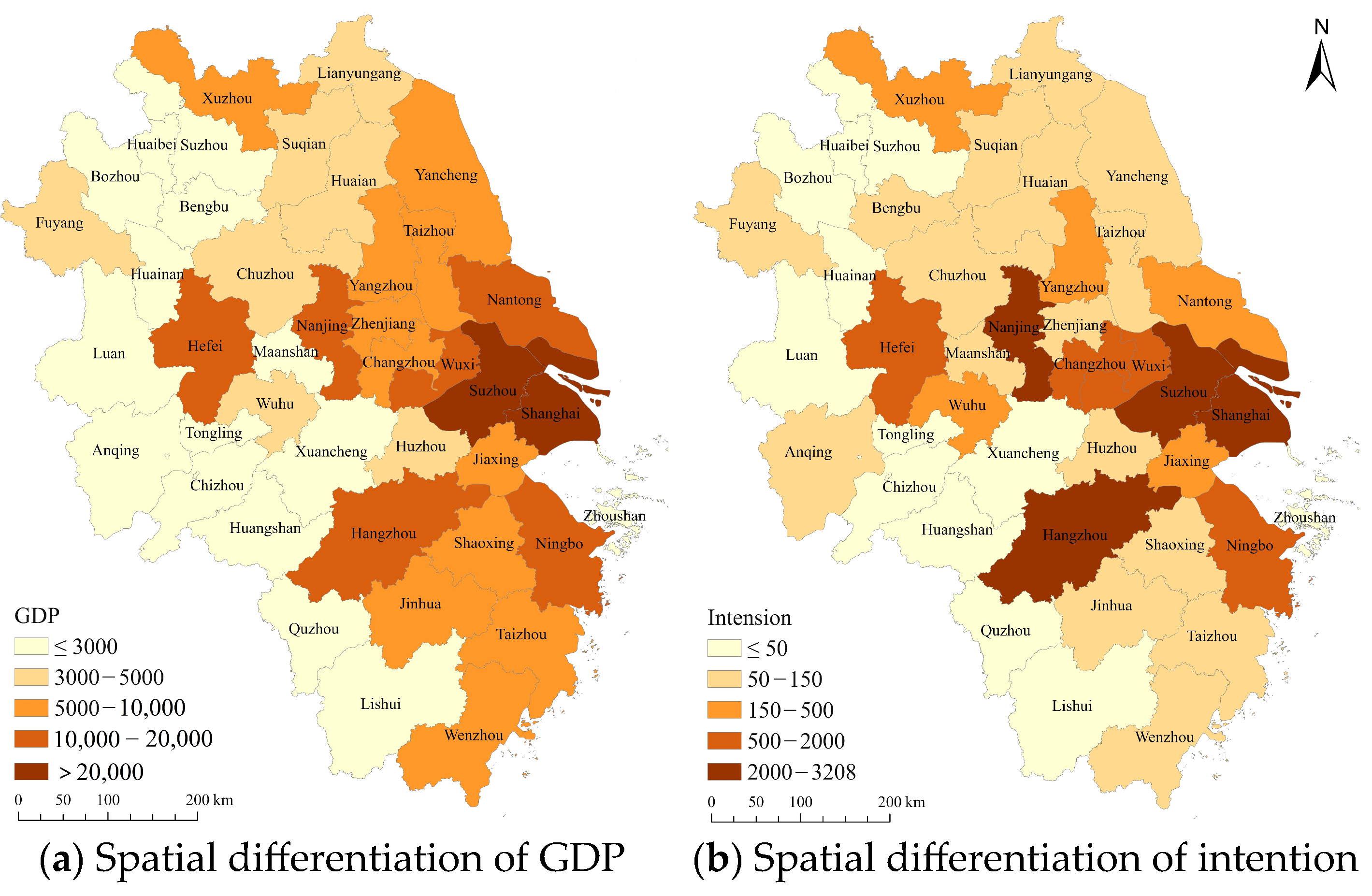

5.1. Threshold Effect Test

Using Stata 16 statistical software, the

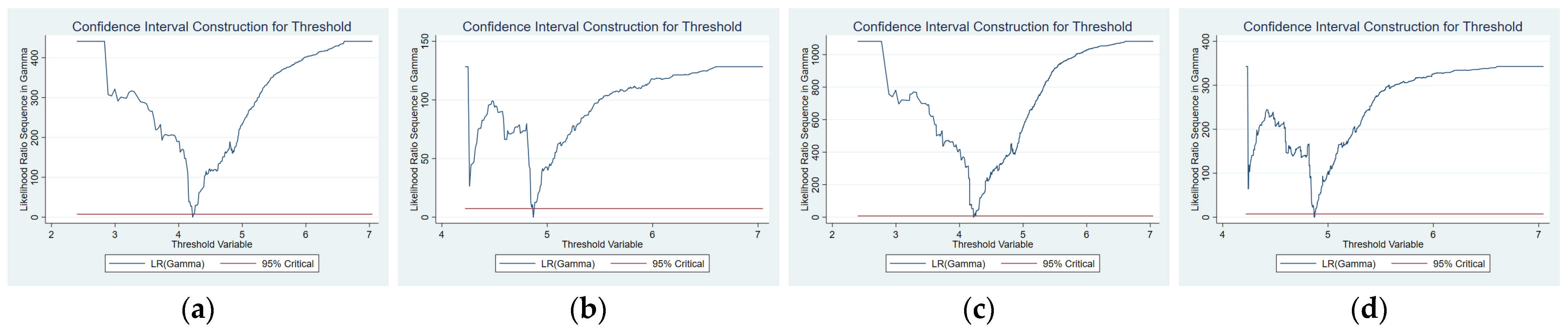

p-values corresponding to the test statistics were derived through 5000 bootstrap replications to determine the presence of threshold effects. When inter-city distance was used as the threshold variable, both the first threshold and the second threshold were found to be statistically significant at the 1% level, as shown in

Table 6, indicating the existence of two statistically significant thresholds in the model.

Table 7 presents the estimated threshold values. The first threshold is estimated at 164.1 km, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 164.1 to 166.4 km. The second threshold is estimated at 271.5 km, with a 95% confidence interval between 271.5 and 284.0 km.

To further verify the robustness of these threshold estimates, we conducted sensitivity analyses regarding the model’s configurations. Specifically, we re-estimated the model under the assumption of heteroskedasticity and varied the trimming proportion for the grid search (ranging from 5% to 15%). The results indicate that the estimated threshold values remained highly consistent across these varying settings, confirming that threshold selection is robust and not driven by specific parameter constraints.

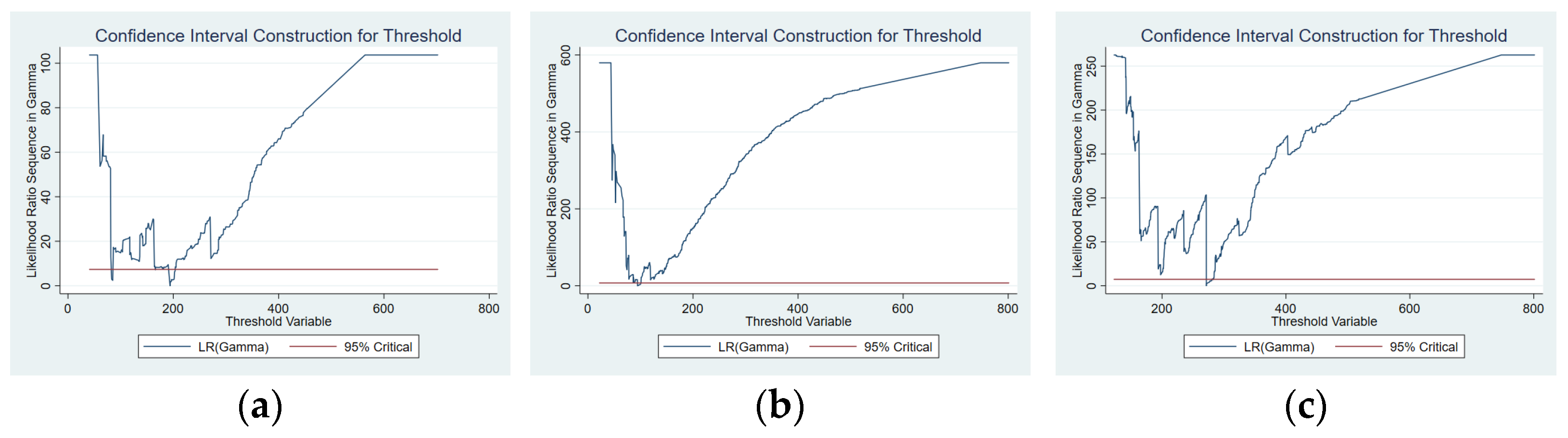

Figure 3 shows the likelihood ratio function plot for the second threshold estimation of inter-city distance. The lowest points of the LR statistics correspond to the true threshold values. Since both values in the figure fall below the critical value indicated by the horizontal line, the two thresholds are statistically significant and valid.

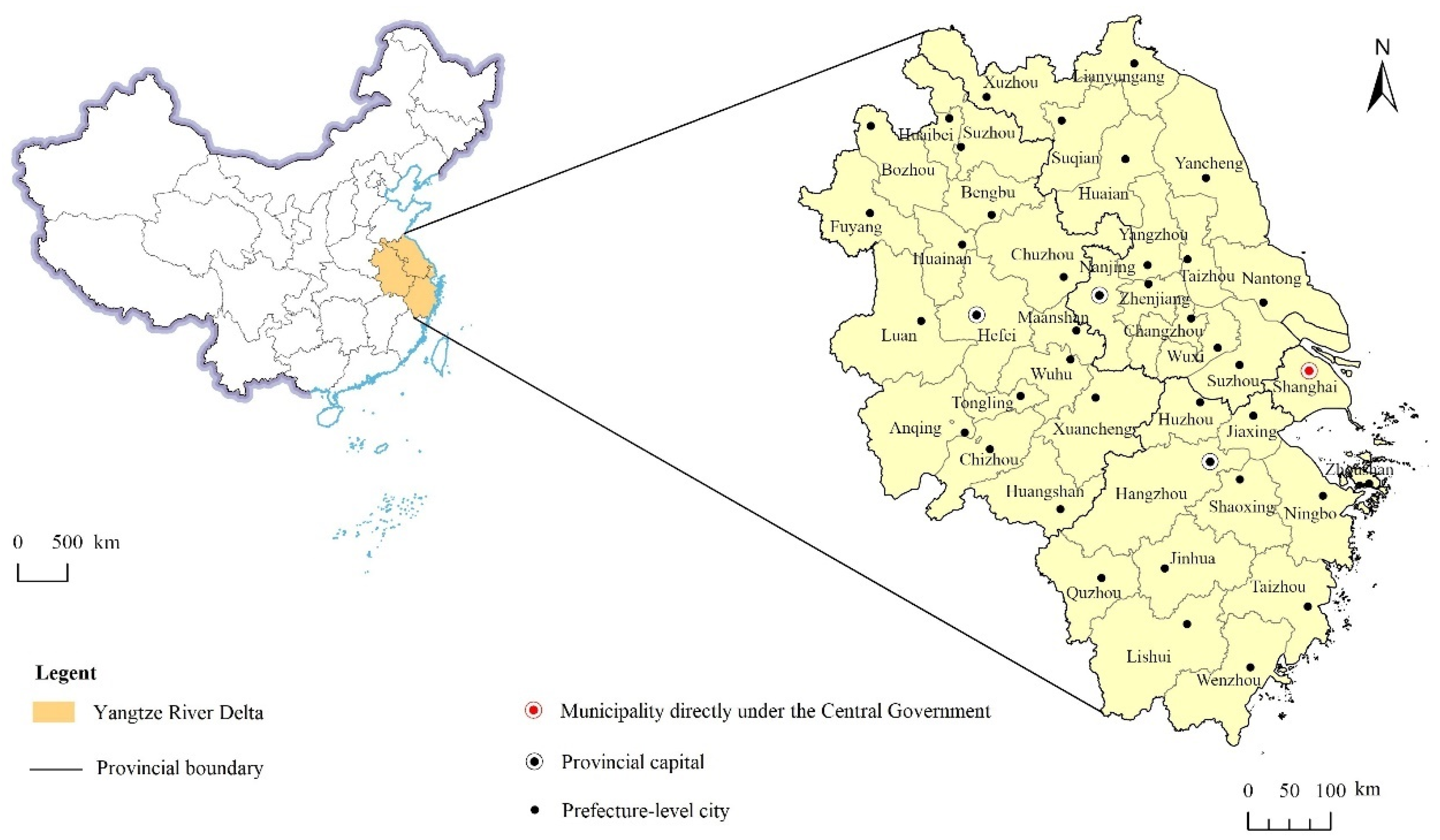

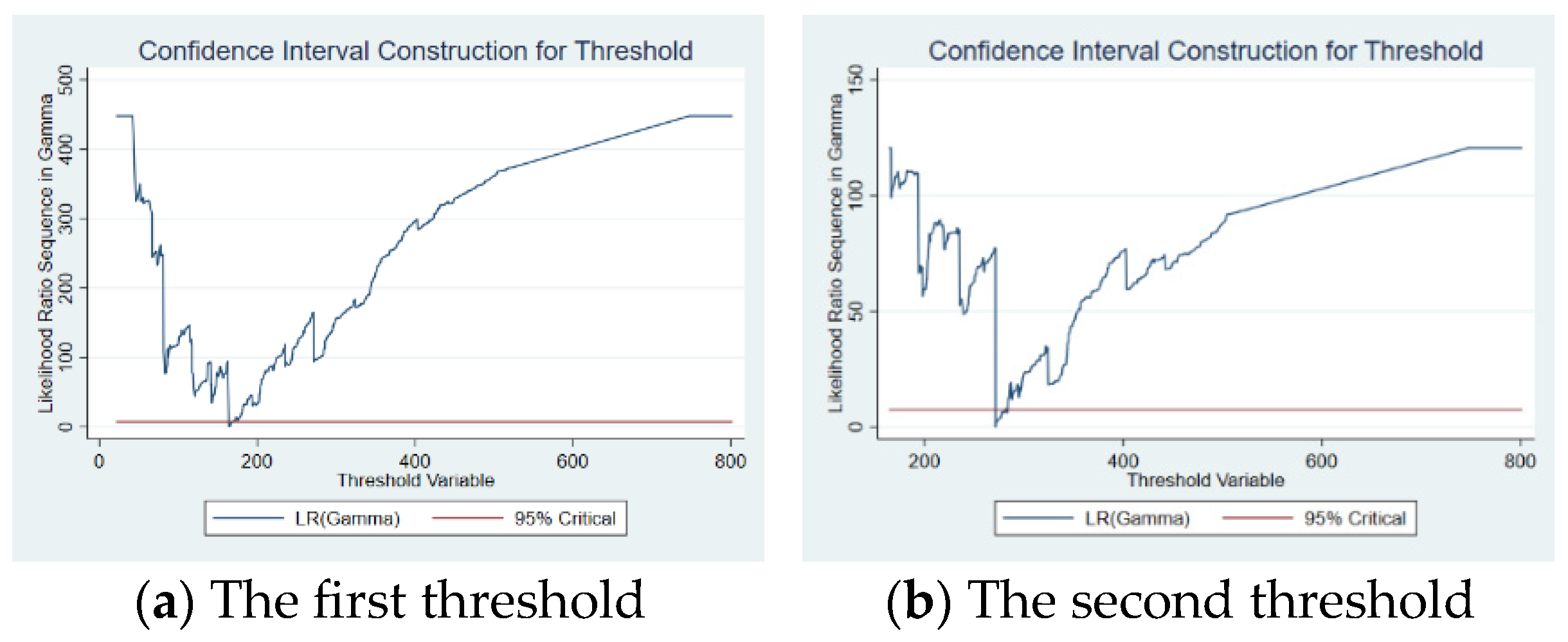

5.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis: Talent Migration in the Yangtze River Delta

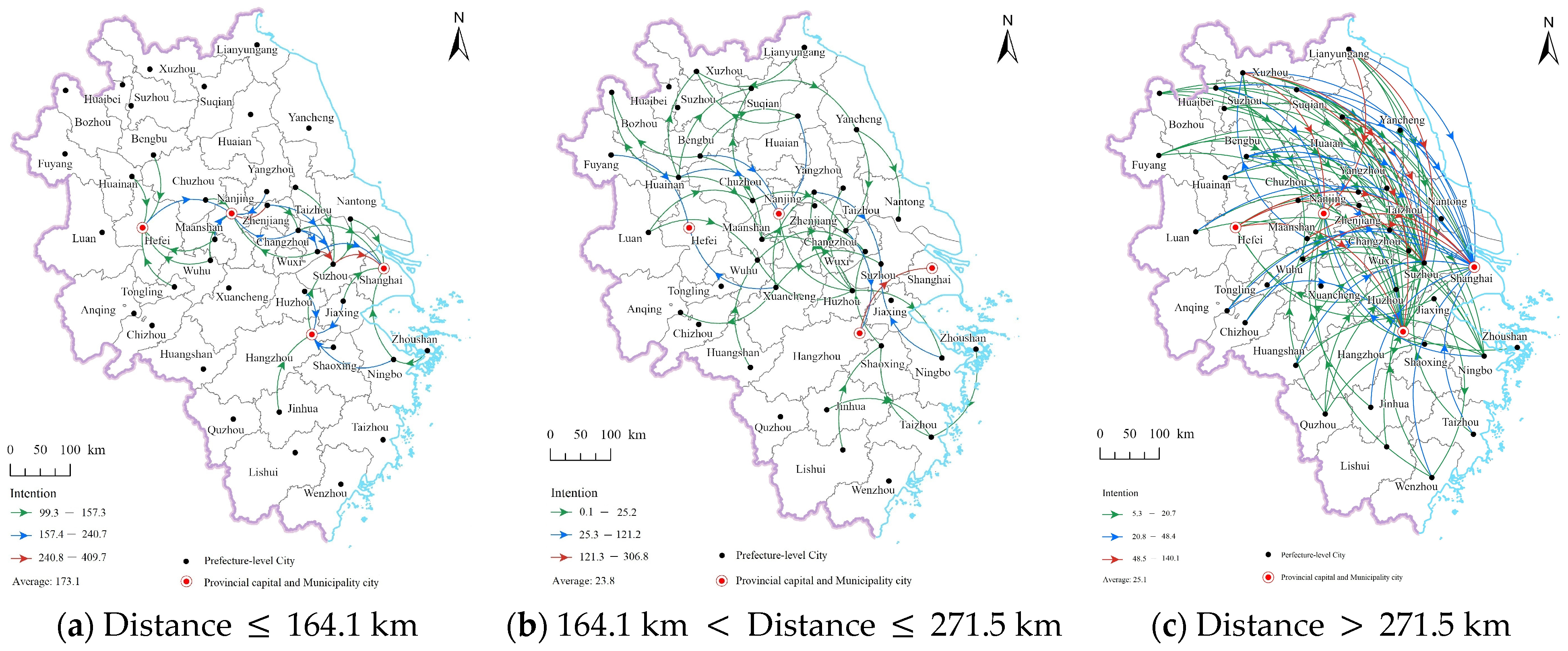

A total of 820 distinct inter-city distance records were obtained (excluding cases where the origin and destination cities are identical). Among these, 162 records exceed 164.1 km, 209 fall within the range of 164.1 km to 271.5 km, and 449 records are greater than 271.5 km, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The top 20% of talent mobility flows across the three distance intervals are visualized in

Figure 5. In the short-distance interval (≤164.1 km), 33 flows are identified, primarily concentrated between cities in southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang. Most of the economically developed cities in the Yangtze River Delta are located within this distance range. The medium-distance interval (164.1–271.5 km) contains 42 flows, mainly connecting northern Anhui, southern Jiangsu, and a few cities in Zhejiang. Unlike the other two intervals, destination cities in this range are not as distinctly concentrated. The long-distance interval (>271.5 km) comprises 90 flows. At these greater distances, talent tends to move from economically less developed cities to higher-tier economic centers such as Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Wuxi, and Changzhou.

A comparison of talent mobility intention across the three intervals reveals distinct patterns. First, values in the short-distance interval range from 99.3 to 409.7, with a mean of 173.1, which is significantly higher than those in the other two intervals. This indicates a substantially stronger willingness to relocate over short distances. Second, the mean mobility intention in the long-distance interval (25.1) is slightly higher than that in the medium-distance interval (23.8). This suggests that mobility intention does not continuously decline with increasing distance; rather, it shows a slight rebound when moving from medium to long distances.

5.3. Economic Level and Talent Mobility Intention

After identifying the threshold values, the original sample was divided into three intervals for cross-sectional threshold regression: distances less than 164.1 km, distances between 164.1 km and 271.5 km, and distances greater than 271.5 km. The results are presented in

Table 8. It can be observed that the coefficients of economic level on talent mobility intention vary across these distance intervals, indicating the presence of a threshold effect and thus supporting Hypothesis 3. The nonlinear influence of economic level manifests specifically as follows:

1. When the distance is ‘short’ (distance ≤ 164.1 km), the coefficient of economic level on talent mobility is 25.710 (p < 0.01), indicating that a higher GDP in the destination city significantly boosts talent mobility intention. This reflects a strong economic driving effect on talent mobility.

On one hand, shorter distances reduce the need for individuals to relocate their families, allow them to retain most of their social networks and resources, and minimize adjustments to lifestyle and cultural habits, thereby lowering the overall cost of mobility. On the other hand, information is more transparent between nearby cities, making it easier for talent to perceive economic opportunities, such as higher salaries, industrial resources, and career development, which are offered by economically developed destinations. This transparency further strengthens mobility intention.

Under these conditions, the economic benefits gained from mobility significantly outweigh the costs, leading talent to prefer moving to economically strong cities within a short distance.

2. When the distance falls in the medium range (164.1 km < distance ≤ 271.5 km), the coefficient of economic level on talent mobility is 3.329 but statistically insignificant. This indicates structural failure of the economic driving mechanism, which can be attributed to two underlying causes.

First, regional industrial isomorphism limits the wage premium. Within the Yangtze River Delta, cities in this medium-distance range frequently share similar industrial structures. Unlike long-distance moves to top-tier financial centers that offer a substantial structural leap in income, relocating between functionally similar cities yields only limited marginal economic gains. The resulting wage gap is often insufficient to offset the associated migration costs, making talent less responsive to aggregate differences in economic size.

Second, a significant mismatch exists between the discontinuous jump in social costs and the prospective economic gains. This distance interval constitutes an awkward zone. It exceeds the practical radius for daily or weekly commuting, thereby disrupting the low-cost social maintenance possible in short-distance moves. Simultaneously, the destination cities lack the overwhelming economic agglomeration effects characteristic of super-metropolises. Faced with a sharp increase in the costs of social detachment and the absence of a compensating salary risk premium, the traditional pull exerted by economic volume alone becomes ineffective.

3. In the long-distance range (distance > 271.5 km), the coefficient of economic level on talent mobility is 2.735 (p < 0.01). Although the magnitude is smaller than in the short-distance range, it remains statistically significant. In this context, talent movement is driven by the high economic capacity of cross-regional hubs.

Although long distances typically involve inter-provincial or cross-regional mobility and entail higher costs, the agglomeration effects of destination cities become prominent, such as Shanghai and southern Jiangsu, as shown in

Figure 5. The strong economic capacity compensates for these costs through notably higher salaries, access to scarce career opportunities, and other advantages, creating a strong attraction that motivates talent to overcome geographical barriers.

4. Compared to the short-distance range (≤164.1 km), the coefficient of economic level in the long-distance range (>271.5 km) is significantly smaller (2.735 vs. 25.710), indicating a weaker marginal effect on talent mobility. This may be attributed to the following reasons:

On one hand, the economic development levels of destination city clusters have already reached a certain threshold. As a result, talent may place greater emphasis on job compatibility and career development opportunities, thereby reducing the marginal effect of economic growth. On the other hand, higher mobility costs require that economic returns be substantial enough to offset these expenses. This effectively raises the threshold for mobility, limiting long-distance relocation to highly competitive or specialized talent who can obtain sufficient benefits from high-level economic centers to justify the costs. Such a screening effect restricts the scale of long-distance mobility, manifesting as a diminished marginal impact of economic level on talent movement.

5.4. Inter-City Distance and Talent Mobility Intention

As shown in

Table 8, the estimated coefficients of distance on talent mobility intention vary significantly across different distance intervals, confirming the existence of a threshold effect and thus supporting Hypothesis 4. The nonlinear influence of inter-city distance manifests as follows:

1. When the inter-city distance is short (distance ≤ 164.1 km), the coefficient of distance on talent mobility intention is −0.278 (p < 0.01), indicating that for every additional kilometer of distance, talent mobility intention decreases by 0.278, demonstrating a strong negative effect. Within the transportation context of the Yangtze River Delta, distances within 164.1 km generally support high-frequency commuting, such as weekly or even same-day round trips. This enables talent to largely retain their original social resources and family support while maintaining lifestyle and cultural adaptability, yet still fully access the economic benefits offered by the destination city. Therefore, within this range, shorter distances strengthen talent mobility intention, whereas increased distance directly undermines this convenience, leading to a significant decline in willingness to move.

2. When the distance falls within the medium range (164.1 km < distance ≤ 271.5 km), its coefficient on talent mobility intention is −0.018 and statistically insignificant. This indicates that within this interval, the marginal deterrent effect of distance weakens.

This can be understood from two perspectives. First, within this range, commuting patterns for personal interaction have largely stabilized. The distance exceeds the threshold that permits weekly travel (approximately 164 km), causing the frequency of interaction to settle at a lower level, such as monthly or quarterly. Consequently, further increases in distance within this band generally do not lead to a substantial change in interaction frequency, rendering it statistically insignificant.

Second, when a journey already requires several hours, adding a few more kilometers of travel does not significantly alter its fundamental nature as a medium-to-long trip. The psychological impact of specific mileage differences on the decision-maker becomes minimal. As a result, mobility intentions in this context are influenced more by non-spatial factors—such as career opportunities, living environment, or family ties—while the weight of distance itself in the decision-making process diminishes.

3. When the inter-city distance is long (distance > 271.5 km), the coefficient of distance on talent mobility intention is −0.011 (p < 0.01), indicating that for every additional kilometer of distance, mobility intention decreases by only 0.011, demonstrating a weak negative effect. Within long-distance ranges, commuting frequency further declines (e.g., from monthly to quarterly). At this point, the marginal impact of increasing distance on commuting frequency stabilizes, while original social networks and family support are almost entirely disrupted. This ‘reset of social capital’ causes mobility decisions to rely more heavily on the economic benefits and personal development opportunities available in the destination city. As a result, the influence of distance gradually diminishes, manifesting as a relatively weak negative effect.

5.5. Endogeneity and Robustness Checks

To ensure the reliability and internal validity of the empirical findings, this section carries out a series of diagnostic tests. First, the two-stage least squares method with an instrumental variable is employed to address potential endogeneity concerns related to economic development. Second, we perform robustness checks by substituting geographic distance with temporal distance metrics to verify the persistence and stability of the threshold effects and by introducing additional controls for housing prices and cultural factors to address omitted variable bias.

5.5.1. Endogeneity Test

While regional economic development attracts talent, the influx of human capital may also drive local economic growth. To rigorously address this endogeneity and isolate the causal effect of economic factors on talent mobility, we employed a two-stage least squares approach using an instrumental variable approach. We constructed a spatially and temporally lagged instrument. Specifically, the IV is defined as the average GDP per capita of geographically adjacent cities over the five-year period from 2017 to 2021. Mathematically, for city

, the instrument

is calculated as follows:

where

denotes the set of cities that share a common border with city

i.

Nk is the number of cities in the set

.

The instrument satisfies both relevance and exclusion conditions. Its relevance is supported by strong regional economic agglomeration and spillover effects, which ensure that the historical economic performance of neighboring cities is closely correlated with the current economic level of the focal city. Meanwhile, the exclusion restriction is upheld because the five-year historical GDP data of neighboring cities are predetermined relative to the current period. It is theoretically implausible that past economic conditions in surrounding cities would directly influence an individual’s present migration decision toward the focal city, except through the channel of the focal city’s own contemporary economic development. The 2SLS estimation results are reported in

Table 9.

The first-stage results demonstrate a strong positive correlation between the instrument and the endogenous variable, with an F statistic of 265.8, well above the conventional threshold of 10, thereby rejecting the null hypothesis of weak instruments. After correcting for endogeneity in the second stage, the coefficient on GDP remains positive and statistically significant at 14.504 (p < 0.05). The qualitative consistency between the IV and baseline OLS estimates confirms the robustness of our main findings and indicates that they are not driven by reverse causality. Thus, the positive pull effect of economic development on talent mobility represents a causal relationship.

5.5.2. Robust Checks

- 1.

Replacing explanatory variable

To verify the robustness of our findings, we substituted geographic distance with temporal distance as the threshold variable. Specifically, we constructed two alternative metrics to capture travel costs:

(1) Rail commute time (RCT). This metric is defined as the minimum travel time between city pairs via direct train connections. Pairs without direct rail links were excluded, resulting in a restricted subsample of 642 observations. (2) Mixed commute time (MCT). To address the sample selection bias in the first method and maintain the full sample size (N = 1640), we supplemented the rail data with estimated travel times. For the 998 city pairs lacking direct rail connections, we estimated the commute time using the formula . These estimates were combined with the rail data to form a complete dataset. All temporal variables were measured in minutes and log-transformed prior to estimation.

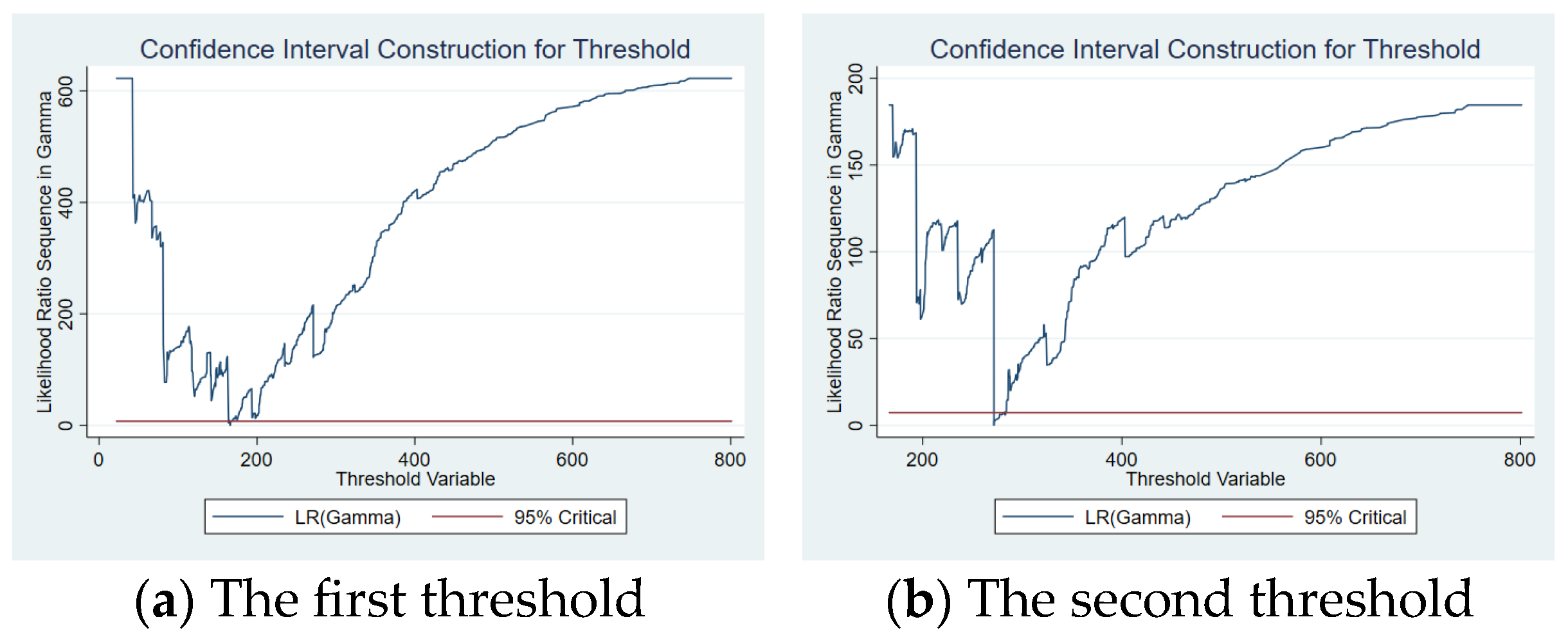

Table 10 presents the threshold estimation results using these temporal distance metrics. The results demonstrate remarkable consistency across both the subsample and the full sample.

Both models identify two highly significant thresholds at nearly identical values, with the first occurring at approximately 4.22 and corresponding to 68 min, and the second at 4.86 and corresponding to 130 min. This consistency implies that the boundary effect of distance on talent mobility is robust regardless of the sample size or the specific measurement of travel cost.

Figure 6 presents the likelihood ratio function graphs for threshold estimation. The horizontal red line in each graph represents the critical value at the 95% confidence level. The confidence intervals for both the RCT and the MCT are extremely narrow. This indicates that the threshold estimates are highly precise and statistically significant, further confirming that the structural break in the influence of distance is robust.

Table 11 presents the estimation results where commuting time serves as both the threshold variable and a key explanatory variable. The results from both the RCT and MCT models are highly consistent, confirming the robustness of our findings. The estimated coefficients show that employing time distance as the threshold variable produces outcomes aligned with the geographic distance model, thereby confirming the robustness of the boundary effect.

- 2.

Controlling Omitted Variables

To mitigate potential omitted variable bias arising from the housing price gradient, innovation environment, and unobserved cultural factors, we re-estimated the model with three additional control variables.

First, we collected average housing price data for the 41 sample cities from

58.com (accessed on 1 January 2025), a leading real estate information platform in China, to control for the cost-of-living gradient. Second, we utilized the logarithm of the number of patent applications (Ln_zl) as a proxy for the regional innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem. Third, to address the concern regarding regional culture and historical context, we introduced dialect distance as a proxy variable. We quantified the cultural distance between city pairs on a scale of 0 to 3, where a value of 0 indicates that the origin and destination belong to the same dialect point, representing the highest degree of cultural similarity, and a value of 3 indicates that they belong to completely different dialect super-groups, representing the lowest degree of cultural similarity. Given that dialect distance offers a more granular and precise measure of cultural proximity than administrative boundaries, we excluded the same-province dummy variable in this specification.

Table 12 reports the threshold estimation results after adding these controls. The tests identify two distinct structural break points at 166.2 km and 271.5 km, both of which are statistically significant at the 1% level. These thresholds divide the spatial interaction into three regimes: a short-distance range (distance ≤ 166.2 km), a medium-distance range (166.2 km < distance ≤ 271.5 km), and a long-distance range (distance > 271.5 km). Notably, the first threshold (166.2 km) remains highly consistent with the baseline model.

Figure 7 displays the likelihood ratio (LR) function for the first and second threshold estimates. The horizontal red line represents the critical value at the 95% confidence level. The threshold parameters are identified where the LR statistic equals zero. As shown, the LR curves intersect the critical value line within narrow intervals, indicating that the confidence intervals are tight and that both threshold estimates are statistically significant and valid.

Table 13 presents the parameter estimates across the three distance intervals. The results demonstrate strong robustness compared to the baseline model. Specifically, the coefficient of distance remains significantly negative in the short-distance regime (−0.297) and the long-distance regime (−0.019), confirming that the distance decay effect persists even after accounting for housing costs, cultural barriers, and innovation capacity.

Similarly, the coefficient of Ln_GDP maintains a consistent pattern with the baseline findings, exhibiting a strong positive driving effect in the short-distance regime (25.69) and a significant but diminished marginal effect in the long-distance regime (8.255). This confirms that the nonlinear mechanism of economic attraction remains robust.

5.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

Subsequent analysis further examines the threshold effects of inter-city distance from the perspectives of education level and age.

5.6.1. Education Level Heterogeneity

In the original sample, job seekers with bachelor’s degrees and those with postgraduate degrees were statistically analyzed separately, and a threshold test was conducted. The results are shown in

Table 14. The difference between

Table 14 and the previous analysis lies in the fact that the first threshold value for bachelor’s degree holders is 142.7, which is lower than that for postgraduate degree holders (164.1 km). This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that bachelor’s degree holders, compared to postgraduates, have weaker capabilities in obtaining long-distance employment information and rely more on localized social networks. As a result, their mobility decisions are constrained by distance at an earlier stage.

Figure 8 presents the likelihood ratio function graphs for threshold estimation across different education levels. The lowest points of the LR statistics represent the true threshold values, all of which are below the critical values shown by the horizontal lines. This confirms that both thresholds are authentic and statistically valid.

Similarly, the different education levels were divided into distinct intervals based on the threshold values and estimated using OLS. To conserve space,

Table 15 only reports the estimation results for inter-city distance and economic level.

Table 15 shows that for postgraduates in the first interval (≤164.1 km), the impact of economic level on mobility intention is positive and significant (10.74), but the coefficient is considerably smaller than that of bachelor’s degree holders (33.85).

This difference suggests that while postgraduates are attracted to economically developed cities, their sensitivity to aggregate economic volume is lower than that of undergraduates. The reason may lie in the high degree of specialization in research fields and career paths among postgraduates. When making mobility decisions, they typically consider not only a destination’s economic capacity but also their own career development platforms. For example, doctoral graduates often prioritize institutional platform levels, such as employment at ‘Double First-Class’ universities or top-tier research institutions, over purely economic volume. Consequently, the marginal utility of destination GDP is somewhat diluted by these non-economic professional requirements, resulting in a weaker economic driving effect compared to bachelor’s degree holders who are more responsive to general labor market opportunities provided by high-GDP cities.

5.6.2. Age Heterogeneity

Based on the original sample, job seekers aged 30 and below and those above 30 were analyzed separately, with threshold tests conducted accordingly. The results are presented in

Table 16.

In the subgroup above 30 years old, the first and second threshold values of city distance are 121 and 164.1 km, respectively, both lower than those in the full sample. This may be attributed to the following reasons.

Job seekers above 30 typically bear greater family responsibilities, including a spouse’s employment, children’s education, and care for elderly parents. Shorter distances facilitate more frequent commuting, which helps mitigate the practical and psychological costs of relocation. Consequently, this demographic exhibits greater sensitivity to distance. Moreover, individuals above 30 are often in the mid-career stage, having accumulated considerable professional experience, industry-specific resources, and localized social networks. Longer distances make it more difficult to leverage these existing career-specific assets, leading to significantly higher opportunity costs compared to those under 30. Hence, the threshold values for distance are lower in this group.

Figure 9 shows the likelihood ratio function plots for threshold estimation across different ages. The lowest points of the LR statistics correspond to the true threshold values. Since all these points fall below the critical values indicated by the horizontal lines, both thresholds are statistically significant.

Table 17 reports the estimated effects of inter-city distance and economic level on talent mobility intention across different distance intervals.

Regarding distance, the threshold of the older group (121 km) is notably lower than that of the younger group (166.2 km), confirming that the spatial range of mobility for individuals above 30 is more restricted.

Furthermore, a distinct reversal is observed in the economic dimension compared to the distance effect. The coefficients for economic level are significantly larger in the younger subgroup compared to the older one (e.g., 35.22 vs. 8.759 in the short-distance range), suggesting that younger job seekers are much more responsive to destination economic capacity. This may be attributed to the fact that younger individuals are in the career accumulation phase and are highly sensitive to the “thick labor market” effects provided by high-GDP cities, actively seeking regions with maximum growth potential. In contrast, those above 30 face higher migration costs and “mooring effects” due to family responsibilities (e.g., children’s education, spousal employment) and established social networks. These factors increase the threshold for relocation, making them less likely to move solely based on the macro-economic level of a destination. Consequently, their mobility intention exhibits lower elasticity to economic development compared to the younger demographic.

5.6.3. Sectoral Heterogeneity

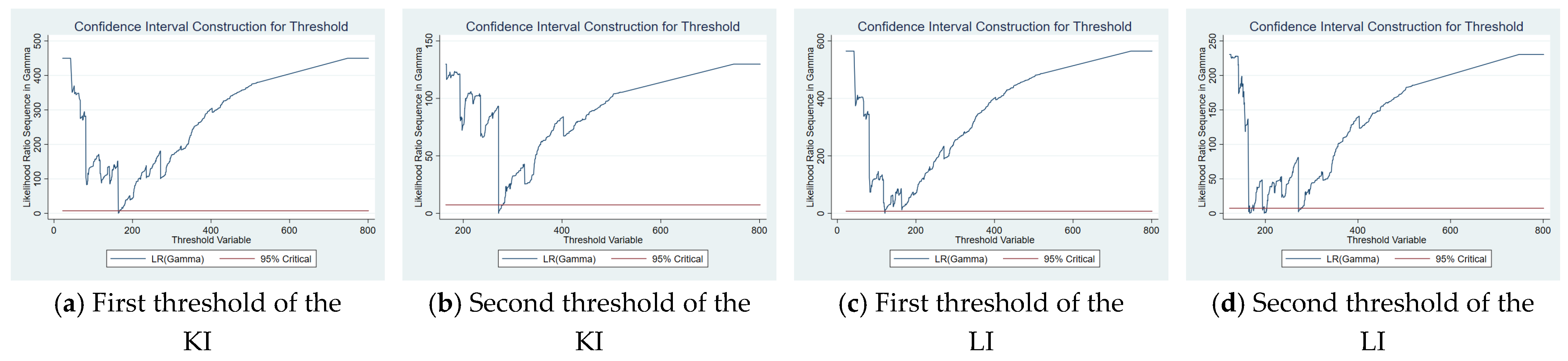

We conduct threshold regression comparisons by selecting two distinct groups from the sample: knowledge-intensive industries (KIs) and labor-intensive industries (LIs). In accordance with the National Economic Industry Classification and Codes, knowledge-intensive industries include Information Transmission, Software, and Information Technology Services (industry codes: J1–J3); Financial Intermediation (J4–J7); Scientific Research and Technical Services (M1–M3); and Business Services (L2). Labor-intensive industries comprise Manufacturing (C1–C31); Construction (E1–E4); Wholesale and Retail Trade (F1–F2); and Accommodation and Catering Services (H1–H2).

Table 18 reports the results of the threshold tests and the estimated threshold values for the distance variable. The double-threshold model shows statistical significance at the 1% level for both industry types. For knowledge-intensive industries, the two threshold values are estimated at 164.1 and 271.5. In contrast, the threshold values for labor-intensive industries are significantly lower, at 121.0 and 166.2. Notably, the first threshold for knowledge-intensive industries (164.1 km) almost coincides with the second threshold for labor-intensive industries (166.2 km). This indicates that talent mobility in labor-intensive industries is more sensitive to distance, whereas talent in knowledge-intensive industries exhibits a broader spatial tolerance.

Figure 10 shows the likelihood ratio function plots for threshold estimation across different industries. The lowest points of the LR statistics correspond to the true threshold values. Since all these points fall below the critical values indicated by the horizontal lines, both thresholds are statistically significant.

Table 19 presents the estimation results for the regime-dependent coefficients, illustrating how the impact of distance and economic scale varies across the identified intervals.

Notably, the coefficients for distance in the labor-intensive (LI) sector are significantly larger in absolute magnitude than those in the knowledge-intensive (KI) sector (e.g., −0.207 vs. −0.037 in the first regime), indicating higher sensitivity to distance among labor-intensive industries. That is, as distance increases, the strength of economic linkage declines more rapidly in the LI group, which is consistent with their lower threshold values discussed earlier. Furthermore, the coefficients for Ln_GDP are consistently larger in the LI sector compared to the KI sector across all regimes, suggesting that labor-intensive industries are more responsive to changes in regional economic size. This may be attributed to the characteristics of labor-intensive products, which typically rely on mass market consumption and scale effects, making the sheer economic volume of a region a stronger motivator for interaction.

5.6.4. City Economic Hierarchy Heterogeneity

Given the significant differences in resource agglomeration capacity and spatial reach among cities at different economic levels, the sample was divided into two groups: Trillion-CNY GDP cities (TC), which include Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Hefei, Suzhou, Ningbo, Wuxi, Changzhou, and Nantong, and Non-trillion-CNY GDP cities (NTC), comprising the remaining cities among the 41 studied. The corresponding threshold estimation results are presented in

Table 20.

As shown in

Table 20, the TC group has a single distance threshold of 193.8 km, whereas the NTC group has two thresholds, at 94.4 km and 271.5 km. First, the fact that only one threshold was identified for the TC group may be attributed to its relatively small sample size (N = 360), which could make it difficult to detect a second threshold. Second, the first threshold of the NTC group (94.4 km) is much smaller than that of the TC group (193.8 km), indicating that cities with smaller economic scale have a shorter effective range for attracting talent.

Figure 11 shows the likelihood ratio function plots for threshold estimation across cities with different GDP values. The lowest points of the LR statistics correspond to the true threshold values. Since all these points fall below the critical values indicated by the horizontal lines, both thresholds are statistically significant.

Table 21 illustrates how distance acts as a friction factor preventing talent flow. In the first regime, the negative coefficient for the NTC group (−0.79) is larger in magnitude than that of the TC group (−0.54). This implies that talent mobility towards smaller cities is highly sensitive to commuting or migration costs; a slight increase in distance significantly deters inflow. Conversely, the high expected returns, e.g., higher wages, and better career prospects in the TC group help offset the friction of distance, making talent less sensitive to geographical barriers. Notably, the economic level is not significant in the TC group. This may be because, for cities in the TC group, the attraction effect of GDP has likely reached saturation, meaning that further GDP growth does not significantly enhance their ability to attract more talent.