Entrepreneurial Signals and External Financing: How Investment Discourse Sentiment Moderates the Effects of Patents and Market Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Signaling Theory

2.1.1. Patent Counts and External Financing

2.1.2. International Market Orientation and External Financing

2.2. Discursive Foundation of Sentiment: Shaping Cognitive Frames

2.2.1. Positive Investment Discourse: Establishing an Optimistic Cognitive Frame

2.2.2. Negative Investment Discourse: Establishing a Pessimistic Cognitive Frame

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Variable Construction

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Analysis

4.2. Regression Results

4.3. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EF | External Financing | IMO | International Market Orientation |

| PC | Patent Count | PID | Positive Investment Discourse |

| NID | Negative Investment Discourse | IDA | Investment Discourse Activation |

| KVBS | Korean Venture Business Survey | LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

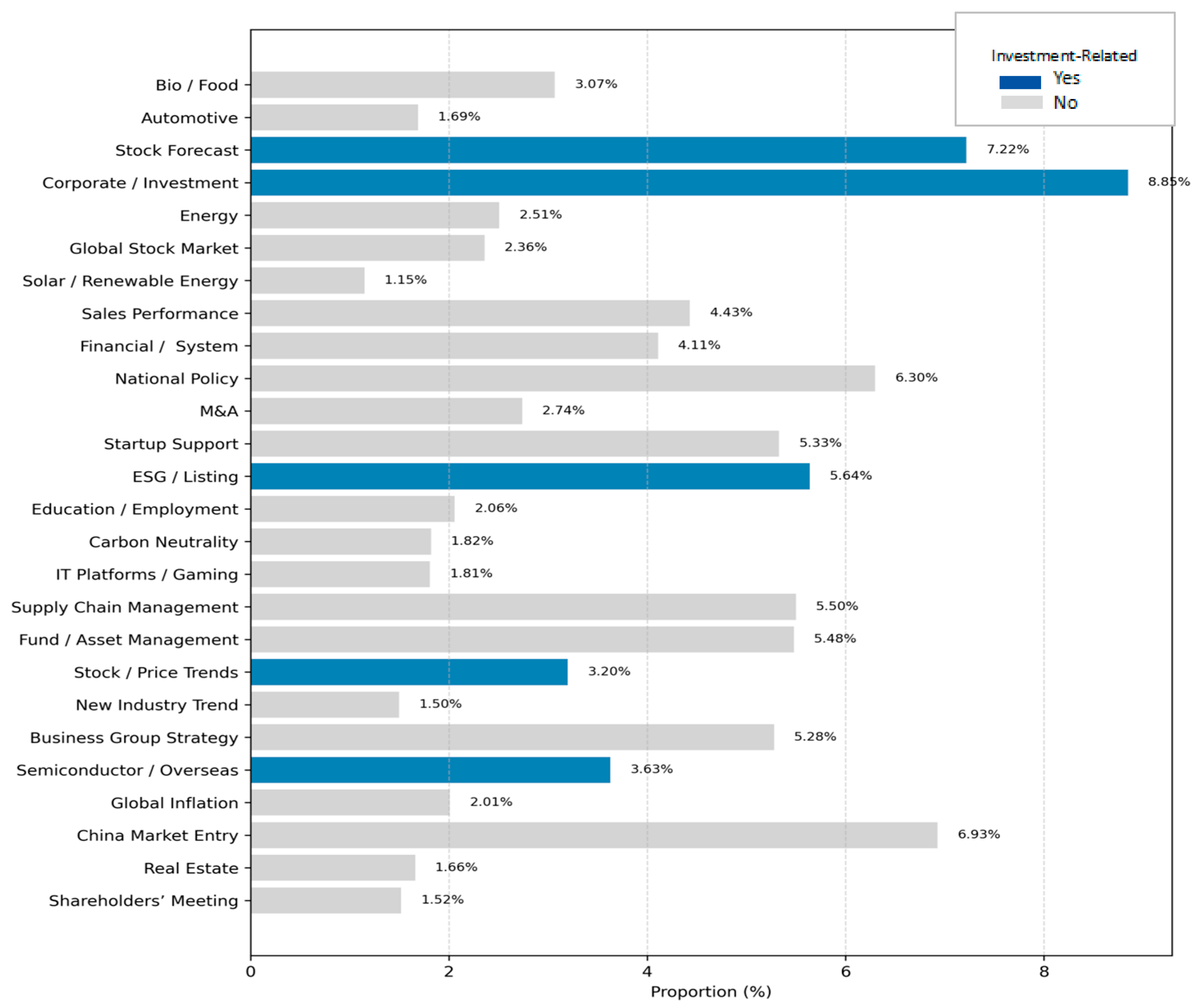

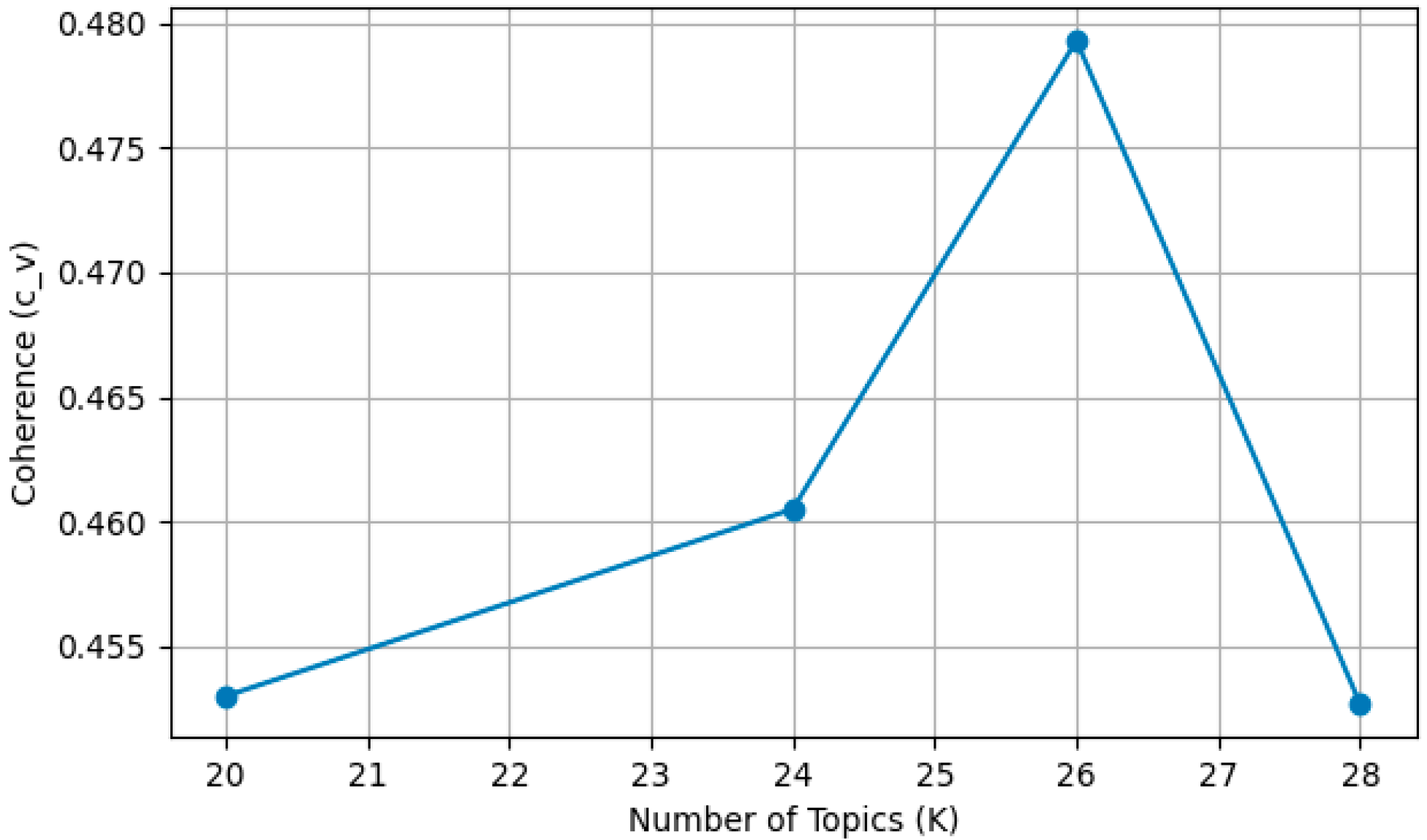

Appendix A. Construction of Investment Discourse Measures

| Topic No. | Topic Label | Proportion (%) | Top_Keywords | Investment Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bio/Food | 3.07 | Bio, brand, market, firm, domestic, food, product | Market |

| 2 | Automotive | 1.69 | Samsung, electronics, automobile, Hyundai, data, subsidy, group | Market/Technology |

| 3 | Stock Forecast | 7.22 | Listing, stock price, stock market, index, investor, firm | Investment |

| 4 | Corporate/Investment | 8.85 | Business, firm, technology, investment, development, intelligence, AI | Investment |

| 5 | Energy | 2.51 | Energy, battery, EV, production, factory, U.S., company | Environment |

| 6 | Global Stock Market | 2.36 | U.S., dollar, time, interest rate, hike, Federal Reserve | Economy |

| 7 | Solar/Renewable Energy | 1.15 | Doosan, solar, purchase, beneficiary, index, sanction, restart | Firm |

| 8 | Sales Performance | 4.43 | Quarter, last year, revenue, this year, performance, profit, billion won | Market |

| 9 | Financial/System | 4.11 | Finance, government, bank, loan, committee, regulation, policy | Policy |

| 10 | National Policy | 6.30 | Korea, government, industry, economy, president, nation, policy | Policy |

| 11 | M&A | 2.74 | Acquisition, sale, contract, bank, holdings, merger, sector | Firm |

| 12 | Startup Support | 5.33 | Firm, startup, entrepreneurship, support, Seoul, innovation, Korea | Policy |

| 13 | ESG/Listing | 5.64 | Firm, management, investment, shareholder, environment, listing, evaluation | Investment |

| 14 | Education/Employment | 2.06 | Talent, education, university, central, manager, Taiwan, workforce | - |

| 15 | Carbon Neutrality | 1.82 | Carbon, IPO, reduction, prediction, solution, chain, progress | Environment |

| 16 | IT Platforms/Gaming | 1.81 | Kakao, dividend, F, universe, NPS, gaming, guide | Market |

| 17 | Supply Chain Management | 5.50 | Recent, supply chain, CEO, people, market, assets, customer | Firm |

| 18 | Fund/Asset Management | 5.48 | Investment, fund, securities, billion won, asset management, size, operation | Market |

| 19 | Stock/Price Trends | 3.20 | Trading, stocks, 10,000 KRW, price, individual investor, surge | Investment |

| 20 | New Industry Trend | 1.50 | AI, Green, Maekyung, treasury, Nvidia, candidate, Maeil Business | Economy |

| 21 | Business Group Strategy | 5.28 | Group, chairman, POSCO, business, CEO, management, global | Firm |

| 22 | Semiconductor/Overseas | 3.63 | Semiconductor, U.S., firm, China, investment, industry, production | Investment |

| 23 | Global Inflation | 2.01 | World, inflation, India, Europe, Asia, UK, behavior | Economy |

| 24 | China Market Entry | 6.93 | China, economy, market, COVID-19, business cycle, world, outlook | Economy |

| 25 | Real Estate | 1.66 | Real estate, construction, complex, city, loss, safety, plant | - |

| 26 | Shareholders’ Meeting | 1.52 | Lotte, tightening, adjustment, memory, opinion, Ray, shareholders’ meeting | Firm |

| Positive Term (KR) | Score | Negative Term (KR) | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | 2 | Crisis | −2 |

| Expectation | 2 | Decline | −2 |

| Innovation | 2 | Uncertainty | −2 |

| Favorable factor | 2 | Failure | −2 |

| Rise | 2 | Loss | −2 |

| Profit | 2 | Sluggishness | −2 |

| Achievement | 2 | Negative | −2 |

| Success | 2 | Adverse factor | −2 |

| Positive | 2 | Decrease | −2 |

| Opportunity | 2 | Risk | −2 |

| Development | 2 | Bearish | −2 |

| Improvement | 2 | Suspension | −2 |

| Improvement | 2 | Recession | −2 |

| Continuation | 2 | Regression | −2 |

| Promising | 2 | Decline | −2 |

| Expansion | 2 | Deterioration | −2 |

| Recovery | 2 | Contraction | −2 |

| Bullish | 2 | Dissatisfaction | −2 |

| Strengthening | 2 | Collapse | −2 |

| Leap | 2 | Abandonment | −2 |

| Year | Positive Discourse Index | Negative Discourse Index |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 2020 | 93.6 | 122.2 |

| 2021 | 93.8 | 78.3 |

| 2022 | 90.1 | 143.8 |

| 2023 | 105.3 | 117.1 |

Appendix B. Diagnostics and Robustness

| Model | Mean VIF | VIF Range | Multicollinearity Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive discourse model (H3–H4) | 1.11 | 1.02–1.19 | None |

| Negative discourse model (H5–H6) | 1.10 | 1.02–1.16 | None |

| Variables | (R1) PC × PID_res | (R2) IMO × PID_res | (R3) PC × NID_res | (R4) IMO × NID_res |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (ln + 1) | 0.027 ** (0.011) | 0.027 ** (0.011) | 0.027 ** (0.011) | 0.027 ** (0.011) |

| IMO | 0.050 * (0.026) | 0.052 * (0.026) | 0.050 * (0.026) | 0.052 * (0.026) |

| PID | 0.263 *** (0.013) | 0.274 *** (0.013) | 0.263 *** (0.013) | 0.274 *** (0.013) |

| PID_res | 0.699 *** (0.026) | 0.783 *** (0.035) | ||

| NID_res | 0.699 *** (0.026) | 0.783 *** (0.035) | ||

| PC × PID_res | 0.100 *** (0.018) | |||

| IMO × PID_res | −0.097 * (0.050) | |||

| PC × NID_res | 0.100 *** (0.018) | |||

| IMO × NID_res | −0.097 * (0.050) | |||

| Controls + Industry FE + Firm age FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 |

| R-squared | 0.5558 | 0.5463 | 0.5558 | 0.5463 |

| External Financing (DV) (ln + 1) | Main Effects Model | Moderation Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| PC (ln + 1) | 0.654 *** (0.130) | 0.610 *** (0.129) | −0.055(0.236) | 0.178 (0.126) | 0.077 (0.100) | 0.139 * (0.080) | |

| IMO | 1.173 *** (0.293) | 1.027 *** (0.288) | 0.948 *** (0.277) | 1.155 *** (0.428) | 0.691 *** (0.182) | 1.187 *** (0.238) | |

| PID | 2.868 *** (0.234) | 2.960 *** (0.298) | |||||

| NID | 1.993 *** (0.067) | 2.275 *** (0.084) | |||||

| PC × PID | 0.329 (0.235) | ||||||

| IMO × PID | −0.309 (0.436) | ||||||

| PC × NID | 0.055 (0.038) | ||||||

| IMO × NID | −0.496 *** (0.092) | ||||||

| Controls + Industry FE + firm age FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −1826.45 | −1831.95 | −1820.05 | −1649.02 | −1650.89 | −1228.29 | −1218.56 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.066 | 0.0632 | 0.0693 | 0.1568 | 0.1558 | 0.3719 | 0.3769 |

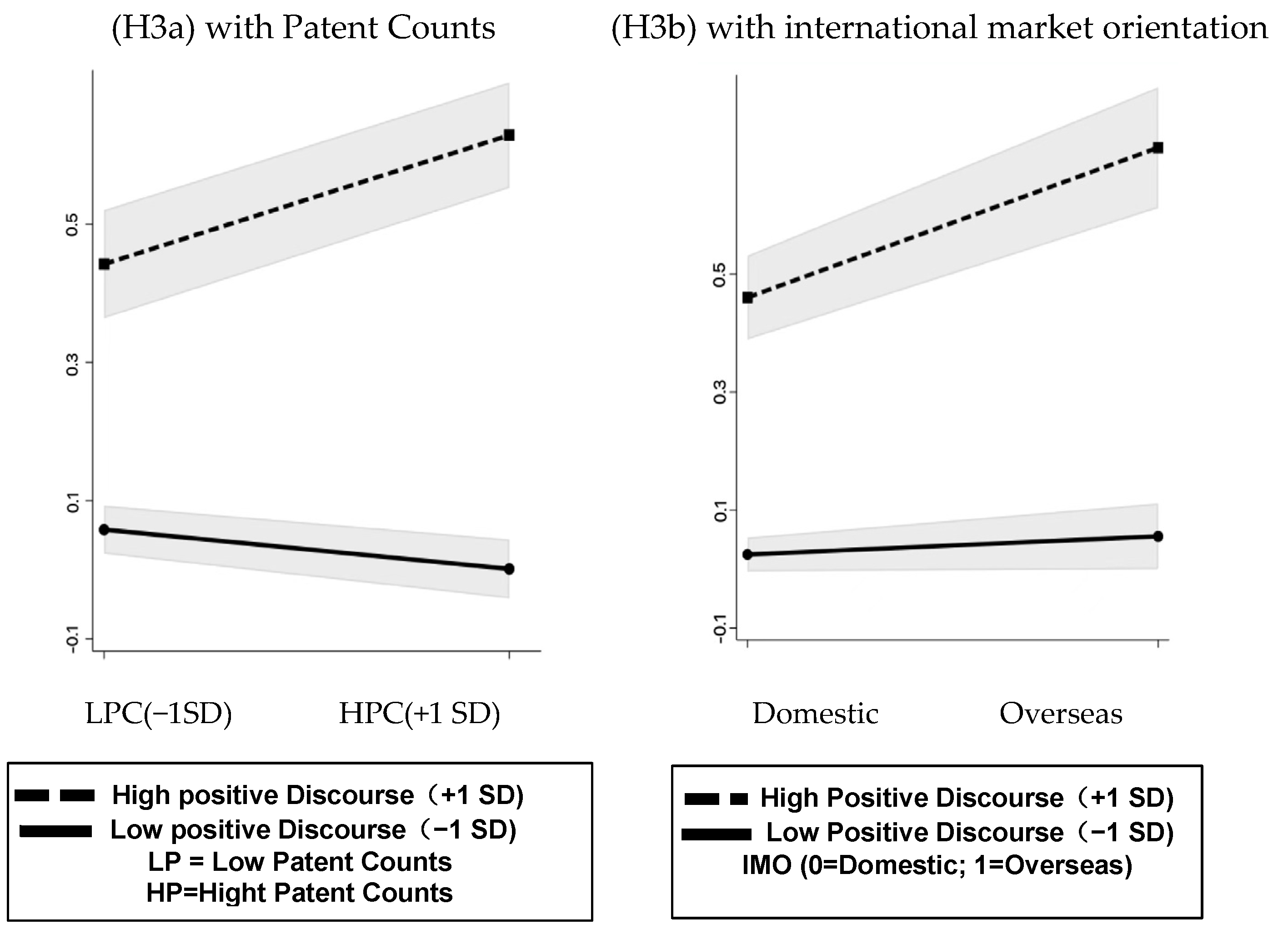

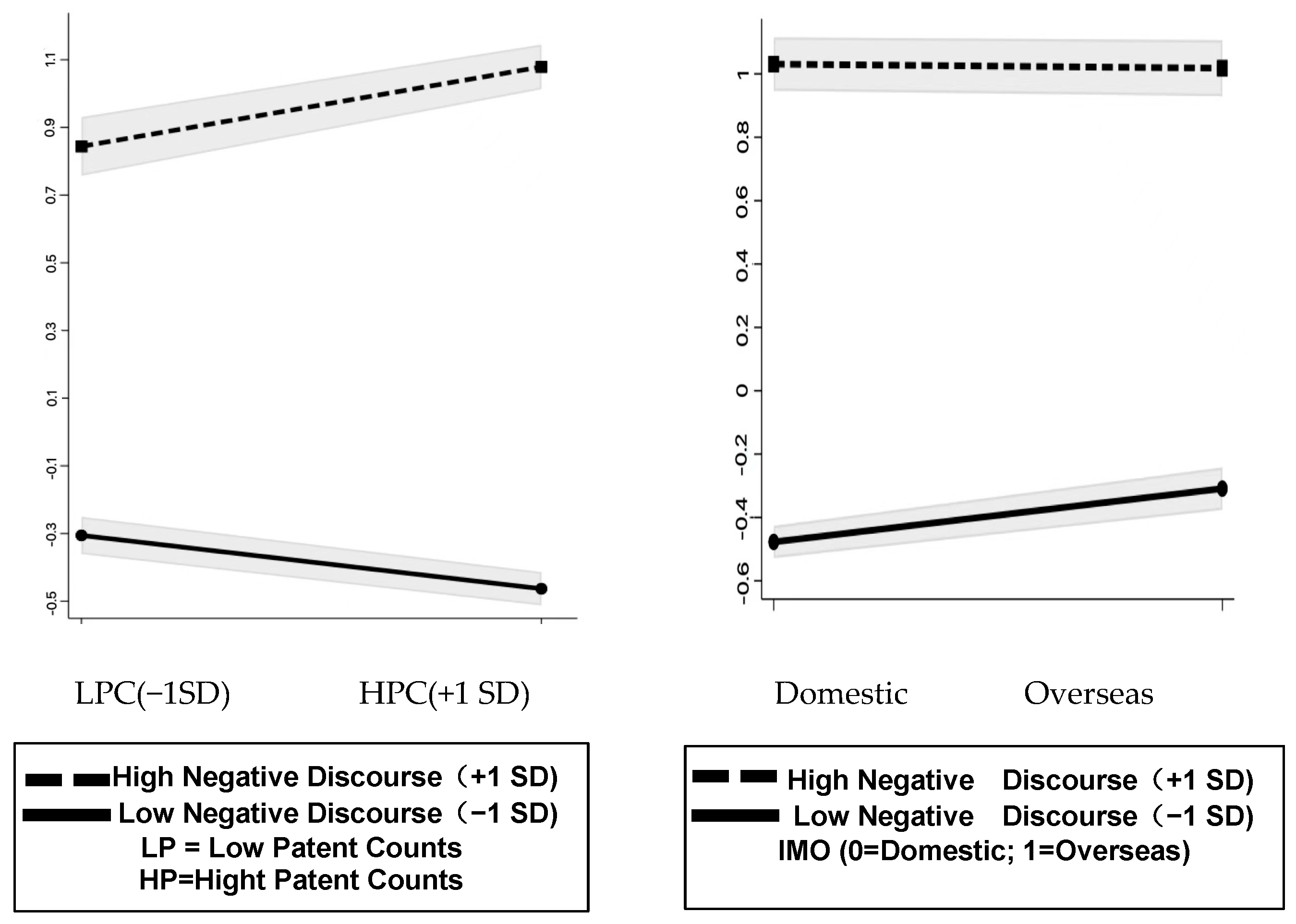

| Variables | (1) Hypothesis 3a | (2) Hypothesis 3b | (3) Hypothesis 4a | (4) Hypothesis 4b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (ln + 1) | 0.044 ** (0.016) | 0.045 ** (0.016) | 0.015 (0.011) | 0.015 (0.011) |

| IMO | 0.099 * (0.038) | 0.102 ** (0.038) | 0.044 * (0.026) | 0.054 * (0.026) |

| PID | 0.210 *** (0.016) | 0.182 *** (0.019) | ||

| NID | 0.693 *** (0.025) | 0.772 *** (0.035) | ||

| PC × PID | 0.043 ** (0.014) | |||

| IMO × PID | 0.072 * (0.036) | |||

| PC × NID | 0.107 *** (0.018) | |||

| IMO × NID | −0.087 * (0.049) |

| Variable | M1 PC Only | M2 IMO Only | M3 PC × PID | M4 IMO × PID | M5 PC × NID | M6 IMO × NID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (ln + 1) | 0.1045 | 0.101 | 0.0428 | 0.044 | 0.0294 | |

| IMO | 0.0582 | 0.052 | 0.0465 | 0.049 | 0.0218 | |

| PID | 0.2557 | 0.22 | ||||

| NID | 0.6849 | |||||

| PC × PID | 0.0683 | |||||

| IMO × PID | 0.054 | |||||

| PC × NID | 0.1222 | |||||

| IMO × NID | ||||||

| N | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 |

| R-squared | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.126 | 0.123 | 0.558 | 0.546 |

References

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Towards an entrepreneurial ecosystem typology for regional economic development: The role of creative class and entrepreneurship. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo, S.T. Influencing initial public offering investors with prestige: Signaling with board structures. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 432–446. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30040731 (accessed on 2 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafera, J.; Kleinert, S. Signaling theory in entrepreneurship research: A systematic review and research agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2023, 47, 2419–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Reutzel, C.R.; DesJardine, M.R.; Zhou, Y.S. Signaling theory: State of the theory and its future. J. Manag. 2025, 51, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, O. The use of signals in new-venture financing: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeussler, C.; Harhoff, D.; Mueller, E. How patenting informs VC investors: The case of biotechnology. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1286–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.H.; Ziedonis, R.H. Resources as dual sources of advantage: Implications for valuing entrepreneurial-firm patents. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Chen, X.P.; Kotha, S.; Fisher, G. Catching fire spreading it: A glimpse into displayed entrepreneurial passion in crowdfunding campaigns. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, D.; Goldfarb, B.; Gera, A. Form or substance: The role of business plans in venture capital decision making. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, A.H.; Short, J.C.; Drover, W.; Stevenson, R.M.; McKenny, A.F.; Allison, T.H. The power of positivity? The influence of positive psychological capital language on crowdfunding performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 470–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, S. The promise of new ventures’ growth ambitions in early-stage funding: On the crossroads between cheap talk and credible signals. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2024, 48, 274–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigenberger, N.; Garz, M.; Cyron, T. Signaling theory in entrepreneurial fundraising and crowdfunding research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2025, 63, 1830–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.A. Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2008, 11, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.A. Taking ideas and discourse seriously: Explaining change through discursive institutionalism as the fourth ‘new institutionalism’. Eur. Politi. Sci. Rev. 2010, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaara, E.; Aranda, A.M.; Etchanchu, H. Discursive legitimation: An integrative theoretical framework and agenda for future research. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 2343–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, P.C. Giving content to investor sentiment: The role of media in the stock market. J. Financ. 2007, 62, 1139–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Z.; Engelberg, J.; Gao, P. In search of attention. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 1461–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, T.G.; Rindova, V.P. Media legitimation effects in the market for initial public offerings. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.M.; McDougall, P.P. Toward a theory of international new ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1994, 25, 45–64. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/154851 (accessed on 15 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.A.; Cavusgil, S.T. Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwens, C.; Zapkau, F.B.; Bierwerth, M.; Isidor, R.; Knight, G.; Kabst, R. International entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis on the internationalization and performance relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 734–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.L.; Marin, A.; Boal, K.B. The impact of media on the legitimacy of new market categories: The case of broadband internet. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Liu, M.; Malik, T.H.; Shi, J. The role of media coverage in the audience’s legitimacy judgment about disruptive innovation: An empirical study of DiDi in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 35, 1128–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, G.K.; Cumming, D.; Günther, C.; Schweizer, D. Signaling in equity crowdfunding. Enterp. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 955–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeley, M.B.; Matusik, S.F.; Jain, N. Innovation, appropriability, and the underpricing of initial public offerings. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 209–225. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20159848 (accessed on 15 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.H.; Jaffe, A.; Trajtenberg, M. Market value and patent citations. RAND J. Econ. 2005, 36, 16–38. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1593752 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Bergh, D.D.; Connelly, B.L.; Ketchen, D.J.; Shannon, L.M. Signaling theory equilibrium in strategic management research: An assessment a research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 1334–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Fosfuri, A.; Gambardella, A. Markets for Technology: The Economics of Innovation and Corporate Strategy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, J.A.; Silverman, B.S. Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Pickernell, D.; Battisti, M.; Nguyen, T. Signalling entrepreneurs’ credibility and project quality for crowdfunding success: Cases from the Kickstarter and Indiegogo environments. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, I.M.; MacGarvie, M.J. Patents, thickets and the financing of early-stage firms: Evidence from the software industry. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 729–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeuscher, K.; Rothe, H. Entrepreneurial framing: How category dynamics shape the effectiveness of linguistic frames. Strateg. Manag. J. 2023, 44, 362–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Prabhala, N.R.; Viswanathan, S. Judging borrowers by the company they keep: Friendship networks and infor-mation asymmetry in online peer-to-peer lending. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Baum, M. Internationalization strategy, firm resources and the survival of SMEs in the export market. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.; Liguori, E.W.; Solomon, S.; Bendickson, J. Technological innovation and the expansion of entrepre-neurship ecosystems. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2023, 17, 1789–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhankangas, A.; Ehrlich, M. How entrepreneurs seduce business angels: An impression management approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L. Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broek, O.M.v.D. How political actors co-construct CSR and its effect on firms’ political access: A discursive insti-tutionalist view. J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 61, 595–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromidha, E.; Córdoba-Pachón, J.-R. Discursive institutionalism for reconciling change and stability in digital in-novation public sector projects for development. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, A.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Reger, R.K.; Shapiro, D.L. Managing the message: The effects of firm actions and industry spillovers on media coverage following wrongdoing. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1079–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.; Kuratko, D.F.; Bloodgood, J.M.; Hornsby, J.S. Legitimate to whom? The challenge of audience diversity and new venture legitimacy. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, P.C.; Saar-Tsechansky, M.; Macskassy, S. More than words: Quantifying language to measure firms’ fundamentals. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1437–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T.; McDonald, B. When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Lim, S.S.; Teoh, S.H. Driven to distraction: Extraneous events and underreaction to earnings news. J. Financ. 2009, 64, 2289–2325. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27735172 (accessed on 18 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.H.; Lerner, J. The financing of R & D and innovation. In Handbook of the Economics of Innovation; Hall, B.H., Rosenberg, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 609–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P.; Lerner, J. The venture capital revolution. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 145–168. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2696596 (accessed on 20 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gripsrud, G.; Hunneman, A.; Solberg, C.A. Speed of internationalization of new ventures and survival in export markets. Int. Bus. Rev. 2023, 32, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O. How media coverage of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility influences cross-border acquisi-tions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Cerciello, M.; Garofalo, A.; Musella, G. Effect of Media News on Radicalization of Attitudes to Immigration. J. Econ. Race Policy 2021, 5, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barde, B.V.; Bainwad, A.M. An overview of topic modeling methods and tools. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 15–16 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannigan, T.R.; Haans, R.F.J.; Vakili, K.; Tchalian, H.; Glaser, V.L.; Wang, M.S.; Kaplan, S.; Jennings, P.D. Topic modeling in management research: Rendering new theory from textual data. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 586–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M.; Brooke, J.; Tofiloski, M.; Voll, K.; Stede, M. Lexicon-based methods for analysis. Comput. Linguist. 2011, 37, 267–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.L.; Cho, S. KoNLPy: Korean natural language processing in Python. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference on Human & Cognitive Language Technology, Chuncheon, Republic of Korea, 10–11 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. Sentiment analysis and opinion mining. In Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzkow, M.; Shapiro, J.M. What drives media slant? Evidence from U.S. daily newspapers. Econometrica 2010, 78, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, E. Can Text-Based Statistical Models Reveal Impending Banking Crises? Comput. Econ. 2024, 65, 1265–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allayioti, A.; Bozzelli, G.; Di Casola, P.; Mendicino, C.; Skoblar, A.; Velasco, S. More Uncertainty, Less Lending: How US Policy Affects Firm Financing in Europe; European Central Bank: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.H.; Colombo, M.G.; Cumming, D.J.; Vismara, S. New players in entrepreneurial finance and why they are there. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 50, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röder, M.; Both, A.; Hinneburg, A. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Shanghai, China, 31 January–6 February 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-M.; Na, C.-W.; Choi, M.-S.; Lee, D.; On, B.-W. BiLSTM-based method for building a KNU Korean lexicon. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2018, 24, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; O’Callaghan, D.; Cunningham, P. How many topics? Stability analysis for topic models. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Proceedings of the European Conference, ECML PKDD 2014, Nancy, France, 15–19 September 2014; Proceedings, Part I; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Calders, T., Esposito, F., Hüllermeier, E., Meo, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8724, pp. 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Sapienza, H.J.; Almeida, J.G. Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P. A Guide to Econometrics, 6th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, G.; Sunstein, C.R.; Golman, R. Disclosure: Psychology changes everything. Ann. Rev. Econ. 2014, 6, 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| (1) External Financing (ln + 1) | 0.319 | 1.009 | 1 | ||||

| (2) PC (ln + 1) | 0 | 1.17 | 0.107 *** | 1 | |||

| (3) IMO | 0.364 | 0.481 | 0.131 *** | 0.107 *** | 1 | ||

| (4) PID | 0 | 1 | 0.274 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.102 *** | 1 | |

| (5) NID | 0 | 1 | 0.721 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.387 *** | 1 |

| (6) R&D intensity | 0.106 | 0.375 | 0.064 *** | −0.043 ** | 0.059 *** | 0.027 | 0.120 *** |

| (7) Innovation level | 3.352 | 0.793 | 0.124 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.111 *** |

| (8) Firm size | 8.547 | 1.852 | −0.030 * | 0.260 *** | −0.072 *** | 0.054 *** | −0.127 *** |

| (9) Founder entrepreneurial experience | 0.163 | 0.369 | 0.095 *** | −0.022 | 0.089 *** | 0.050 ** | 0.095 *** |

| (10) Founder work experience (ln) | 2.063 | 1.052 | 0.056 *** | 0.081 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.082 *** |

| (11) Founder gender | 1.052 | 0.223 | −0.020 | −0.061 *** | −0.005 | 0.009 | 0.004 |

| (12) Founder education level | 2.808 | 1.011 | −0.173 *** | −0.148 *** | −0.167 *** | −0.007 | −0.143 *** |

| Variables | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| (6) R&D intensity | 1 | ||||||

| (7) Innovation level | 0.088 *** | 1 | |||||

| (8) Firm size | −0.306 *** | 0.039 ** | 1 | ||||

| (9) Founder entrepreneurial experience | 0.052 *** | 0.043 ** | −0.073 *** | 1 | |||

| (10) Founder work experience (ln) | −0.010 | 0.153 *** | 0.041 ** | 0.104 *** | 1 | ||

| (11) Founder gender | 0.011 | 0 | −0.111 *** | 0.031 * | −0.064 *** | 1 | |

| (12) Founder education level | −0.085 *** | −0.148 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.036 ** | 0.054 ** | 1 |

| External Financing (DV)(ln + 1) | Baseline (Controls Only) | Main Effects Model | Moderation Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| PC (ln + 1) | 0.087 *** (0.017) | 0.084 *** (0.017) | 0.036 ** (0.015) | 0.037 ** (0.016) | 0.025 ** (0.011) | 0.025 ** (0.011) | ||

| IMO | 0.119 * (0.040) | 0.106 *** (0.039) | 0.095 ** (0.038) | 0.100 *** (0.037) | 0.044 * (0.026) | 0.053 ** (0.026) | ||

| PID | 0.251 *** (0.017) | 0.216 *** (0.021) | ||||||

| NID | 0.695 *** (0.025) | 0.777 *** (0.035) | ||||||

| PC × PID | 0.059 *** (0.016) | |||||||

| IMO × PID | 0.088 ** (0.038) | |||||||

| PC × NID | 0.102 *** (0.018) | |||||||

| IMO × NID | −0.093 * (0.048) | |||||||

| R&D intensity | 0.100 * (0.059) | 0.089 (0.058) | 0.097 * (0.058) | 0.087 (0.058) | 0.069 (0.052) | 0.062 (0.051) | −0.011 (0.048) | −0.018 (0.050) |

| innovation level | 0.104 *** (0.024) | 0.083 *** (0.024) | 0.090 *** (0.025) | 0.072 *** (0.025) | 0.034 (0.025) | 0.037 (0.025) | 0.030 (0.019) | 0.019 (0.019) |

| Firm size | 0.009 (0.012) | 0.000 (0.012) | 0.010 (0.012) | 0.002 (0.012) | 0.001 (0.012) | 0.000 (0.012) | 0.040 *** (0.009) | 0.042 *** (0.009) |

| Founder entrepreneurial experience | 0.251 *** (0.056) | 0.246 *** (0.055) | 0.240 *** (0.056) | 0.237 *** (0.055) | 0.231 *** (0.053) | 0.226 *** (0.053) | 0.096 ** (0.038) | 0.086 ** (0.038) |

| Founder work experience (dummy) | 0.029 * (0.016) | 0.025 (0.016) | 0.020 (0.016) | 0.016 (0.016) | −0.039 ** (0.016) | −0.032 ** (0.016) | −0.023 * (0.012) | −0.023 * (0.012) |

| Founder gender | −0.082 (0.060) | 0.085 (0.059) | −0.082 (0.060) | −0.085 (0.059) | −0.122 ** (0.057) | −0.123 ** (0.058) | −0.084 * (0.043) | −0.079 * (0.045) |

| Founder education level | −0.138 *** (0.018) | −0.122 *** (0.017) | −0.131 *** (0.017) | −0.117 *** (0.017) | −0.124 *** (0.017) | −0.123 *** (0.017) | −0.055 *** (0.013) | −0.056 *** (0.013) |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm age FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.397 ** (0.158) | 0.527 *** (0.161) | 0.378 ** (0.158) | 0.506 *** (0.161) | 0.829 *** (0.160) | 0.815 *** (0.163) | 0.138 (0.125) | 0.167 (0.127) |

| N | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 | 3456 |

| R-squared | 0.055 | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.066 | 0.126 | 0.123 | 0.558 | 0.546 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

An, L.; Kang, S.; Lee, W.J. Entrepreneurial Signals and External Financing: How Investment Discourse Sentiment Moderates the Effects of Patents and Market Orientation. Sustainability 2026, 18, 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010421

An L, Kang S, Lee WJ. Entrepreneurial Signals and External Financing: How Investment Discourse Sentiment Moderates the Effects of Patents and Market Orientation. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010421

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Lanfang, Shinhyung Kang, and Woo Jin Lee. 2026. "Entrepreneurial Signals and External Financing: How Investment Discourse Sentiment Moderates the Effects of Patents and Market Orientation" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010421

APA StyleAn, L., Kang, S., & Lee, W. J. (2026). Entrepreneurial Signals and External Financing: How Investment Discourse Sentiment Moderates the Effects of Patents and Market Orientation. Sustainability, 18(1), 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010421