Sustainable Development Agenda Pilot Zones Policy, Entrepreneurial Green Attention and Corporate Green Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Institutional Background and Theoretical Hypotheses

2.1. Policy Background

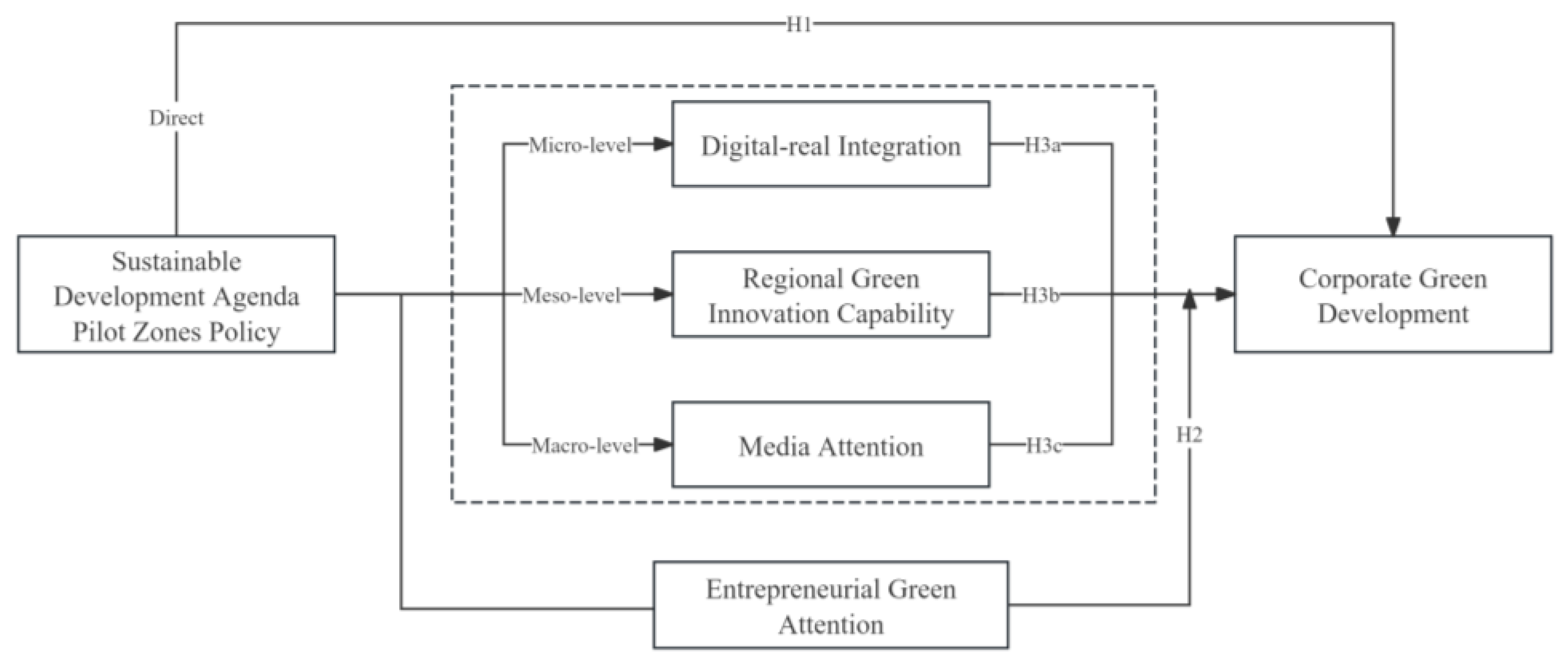

2.2. Theoretical Hypotheses

3. Research Design and Data

3.1. Samples and Data

3.2. Variable Specification

3.3. Model Specification

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Baseline Regression

4.3. Endogeneity Test

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Parallel Trends Test

4.4.2. Placebo Test

4.4.3. Other Robustness Tests

- Excluding Interference from Competitive Policies

- 2.

- Excluding the Impact of Exceptional Periods

- 3.

- PSM-DID

5. Results of Further Analysis

5.1. Moderating Effect Analysis

5.2. Mechanism Analysis

5.2.1. Corporate Digital–Real Integration

5.2.2. Regional Green Innovation Capability

5.2.3. Media Attention

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.1. Heterogeneity in the Nature of Ownership

5.3.2. Heterogeneity in Pollution Intensity

5.3.3. Heterogeneity in Regional Development

5.3.4. Heterogeneity in Government Environmental Attention

5.4. Unintended Consequences

5.4.1. The Impact of the SDA Policy on Corporate Green Innovation Bubbles

5.4.2. The Impact of the SDA Policy on the Quality of Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure

6. Discussion

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Disclosure Type | Disclosure Item | Scoring Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Management Disclosure | Environmental Philosophy | Disclosure: 2 points No Disclosure: 0 points |

| Environmental Objectives | ||

| Environmental Management System | ||

| Environmental Education and Training | ||

| Special Environmental Actions | ||

| Environmental Incident Emergency Mechanism | ||

| Environmental Honors or Awards | ||

| “Three Simultaneities” System | ||

| Environmental Certification Disclosure | ISO 14001 [65] Certification | Yes: 2 points No: 0 points |

| ISO 9001 Certification | ||

| Environmental Information Disclosure Medium | Annual Report | Disclosure: 2 points No Disclosure: 0 points |

| Social Responsibility Report | ||

| Environmental Report | ||

| Environmental Liability Disclosure | Wastewater Discharge | Quantitative and Qualitative Description: 2 points Qualitative Only: 1 point No Disclosure: 0 points |

| COD Emissions | ||

| SO2 Emissions | ||

| CO2 Emissions | ||

| Soot and Dust Emissions | ||

| Industrial Solid Waste Discharge | ||

| Waste Gas Emission Reduction and Treatment | ||

| Wastewater Reduction and Treatment | ||

| Environmental Performance and Governance Disclosure | Dust and Soot Treatment | |

| Solid Waste Utilization and Disposal | ||

| Noise, Light Pollution, Radiation Control | ||

| Cleaner Production Implementation |

References

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, Y. Constructing demonstration zones to promote the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Lanoie, P. Does it pay to be green? A systematic overview. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Stavins, R.N. Dynamic incentives of environmental regulations: The effects of alternative policy instruments on technology diffusion. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1995, 29, S43–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C.V.D. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Oates, W.E.; Portney, P.R. Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Fan, X.; Wu, J. Land regulation and green technological innovation: Evidence from China. JAPE 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Wang, D. Targeted Sustainable Development Policies and Corporate Green Innovation: An Analysis Based on the First Batch of National Sustainable Development Agenda Innovation Demonstration Zones. For. Econ. Manag. 2025, 47, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Meng, Z. Understanding the efficiency and evolution of China’s Green Economy: A province-level analysis. Energy Environ. 2025, 34, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Clelland, I. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 1–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, M.B.U.; Man, Y. Environmental violation and cost of equity capital —Evidence from Europe. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 6369–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xiao, K. The Impact of Green Finance Policy on Environmental Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Lu, Y.; Wu, M.; Yu, L. Does environmental regulation drive away inbound foreign direct investment? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassier, D.G.; Earnhart, D. The effect of clean water regulation on profitability: Testing the Porter hypothesis. Land. Econ. 2010, 82, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C.; Rennings, K. Determinants of eco-innovations by type of environmental impact—The role of regulatory push/pull, technology push and market pull. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 78, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, A.; Deng, S.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J. How Does Digital Consumption Affect Corporate Innovation Activity? Evidence from China’s Information Consumption Pilot Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Pan, T. The impact of green credit on green transformation of heavily polluting enterprises: Reverse forcing or forward pushing? Energ. Policy 2024, 184, 113901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.S.; Fainshmidt, S.; Ambos, T.; Haensel, K. The attention-based view and the multinational corporation: Review and research agenda. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochet, F.; Loumioti, M.; Serafeim, G. Speaking of the short-term: Disclosure horizon and managerial myopia. Rev. Account. Stud. 2015, 20, 1122–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yan, Y.; Jia, X.; Wang, T.; Chai, M. The impact of executives’ green experience on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, X.; Duan, L. How Does CEO’s Environmental Awareness Affect Technological Innovation? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Hao, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, H.; Ba, N. Digitalization and energy: How does internet development affect China’s energy consumption? Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Sun, M. Digital infrastructure policies, local fiscal and financing constraints of Non-SOEs: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0327294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cui, X.; Li, Z. Research on the impact of digital-realistic integration to promote sustainable development of enterprises: Based on the perspective of technology bias. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 21582440251329725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Nutakor, F.; Minlah, M.K.; Li, J. Can digital transformation drive green transformation in manufacturing companies?—Based on socio-technical systems theory perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D. International innovation and diffusion of air pollution control technologies: The effects of NOX and SO2 regulation in the US, Japan, and Germany. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2006, 51, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Balice, A.; Dangelico, R.M. Environmental strategies and green product development: An overview on sustainability-driven companies. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2009, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Supriyadi, A.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Cirella, G.T. Effects of Regional Innovation Capability on the Green Technology Efficiency of China’s Manufacturing Industry: Evidence from Listed Companies. Energies 2020, 13, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C. Energy transition in Germany and regional spill-overs: The diffusion of renewable energy in firms. Energ. Policy 2018, 121, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, C.; Xue, B. Could the construction of sustainable development pilot zones improve the urban environment efficiency in China? Growth Change 2020, 2020, 7678525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W. The globalization of corporate environmental disclosure: Accountability or greenwashing? Organ. Environ. 2011, 2, 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Sun, Z.; Feng, H. Can media attention promote green innovation of Chinese enterprises? Regulatory effect of environmental regulation and green finance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, G.; Jiahui, L. Media attention, green technology innovation and industrial enterprises’ sustainable development: The moderating effect of environmental regulation. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 79, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, J. The road to green innovation in agriculture: The impact of green agriculture demonstration zone on corporate green innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2023, 30, 120340–120354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongyi, D.; Qiongwen, C. Digital innovation, entrepreneurship and green development of manufacturing enterprises. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 45, 84. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality management systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Tian, J.; Cheng, Q.; Xue, R.; Han, Y.; Shan, Y. A dataset on corporate sustainability disclosure. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Illescas, G.; Zebedee, A.A.; Zhou, L. Hear me write: Does CEO narcissism affect disclosure? J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Enterprise digital transformation and capital market performance: Empirical evidence from stock liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, A.C.; Larcker, D.F.; Wang, C.C.Y. How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 144, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, H. Local–neighborhood effect of green technology of environmental regulation. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 1, 100–118. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Sun, Y.J.; Chen, D.K. Government air pollution control effect evaluation—An empirical study from China’s low-carbon city construction. Manag. World 2019, 35, 95–108, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P.; Dechezleprêtre, A.; Hémous, D.; Martin, R.; Van Reenen, J. Carbon taxes, path dependency, and directed technical change: Evidence from the auto industry. J. Polit. Econ. 2016, 124, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Chen, D..; Hu, L. Enterprise Digital-Real Technology Integration and the Development of New Quality Productivity: Empirical Evidence from Enterprise Patent Information. East. China Econ. Manag. 2025, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, H. How does digital transformation drive green total factor productivity? Evidence from Chinese listed enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 136954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Li, L.; Pang, G. Does the integration of digital and real economies promote urban green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S..; Sun, Q..; Qiao, H. Tailoring Measures to Local Conditions for Building a Beautiful China: The Economic Effects of Yangtze River Basin Governance. World Econ. 2025, 48, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.J.; Tai, H.W.; Cao, Z.X.; Wei, C.C.; Cheng, K.T. Green innovation ecosystem evolution: Diffusion of positive green innovation game strategies on complex networks. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X..; Li, H..; Kong, X. Research on the Impact of Party Organization Governance on Corporate ESG Performance. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2022, 1, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Guo, X.; Yue, P. Media coverage and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mai, W. Investor attention and environmental performance of Chinese high-tech companies: The moderating effects of media attention and coverage sentiment. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.J.; Tan, J.; Zhao, L.; Karim, K. In the name of charity: Political connections and strategic corporate social responsibility in a transition economy. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 32, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Haq, I.U.; Wang, J. Nudging toward internal and external origin drivers: A review of corporate green innovation research. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241288750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jin, S.; Ni, J.; Peng, K.; Zhang, L. Strategic or substantive green innovation: How do non-green firms respond to green credit policy? Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, R. ESG rating disagreement and corporate green innovation bubbles: Evidence from Chinese A-share listed firms. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Xie, G. ESG divergence and corporate strategic green patenting. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Du, K.; Yao, X. Stringent environmental regulation and inconsistent green innovation behavior: Evidence from air pollution prevention and control action plan in China. Energy Econ. 2023, 120, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wei, J.; Ji, M. The Impact of Environmental Protection Fee-to-Tax Reform on Corporate Green Information Disclosure. Secur. Mark. Her. 2021, 8, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, J. An evaluation of environmental disclosures made in corporate annual reports. Account. Organ. Soc. 1982, 7, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Qu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W. Strategic reaction to environmental regulation: The combined effect on earnings management and environmental information disclosure. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2025, 31, 1894–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

| Green Development | Dimensional Type | Indicator Type | Specific Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Development | Economic Profit | Return on Total Assets (+) | The ratio of a company’s total net profit to its average total assets |

| Net Profit Growth Rate (+) | The growth rate of the company’s current net profit compared to the previous period’s net profit | ||

| Inventory-to-Revenue Ratio (+) | Inventory/Operating Revenue | ||

| Net Fixed Assets (+) | Original value of fixed assets minus accumulated depreciation and impairment provisions | ||

| Total Factor Productivity (+) | TFP is calculated using the Fixed Effects (FE) method | ||

| Firm Size | The logarithm of the company’s total assets | ||

| Operating Costs (−) | (Cost of main business) + (Cost of other businesses) | ||

| Selling Expenses (−) | Sum of all sales expenditure costs | ||

| Administrative Expenses (−) | Various expenses incurred by the enterprise’s administrative department for managing and organizing business activities, including company expenses, labor union dues, employee education expenses, labor insurance premiums, unemployment insurance premiums, board of directors fees, consulting fees, audit fees, etc. | ||

| Social Value | Earnings Per Share (+) | Earnings Per Share = (Current Period Net Profit − Preferred Dividends)/Weighted Average Total Shares Outstanding for the Year | |

| Compensation Paid to Employees (+) | Total compensation paid to employees | ||

| Number of Employees (+) | The natural logarithm of the number of employees | ||

| Environmental Benefit | Number of Green Patent Applications (+) | The quantity of green patent applications identified according to the WIPO International Green Patent Classification List | |

| Environmental Tax Intensity (+) | The ratio of the logarithm of main business revenue to the natural logarithm of environmental tax | ||

| ISO9001 Certification (+) | Assigned a value of 1 if the enterprise has passed ISO9001 certification, otherwise 0 |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained Variable | Corporate Green Development | GREEN | Comprehensive index of corporate green development |

| Explanatory Variable | Sustainable Development Agenda Pilot Zones Policy | Pilot × Post | The policy effect is identified by constructing a policy treatment variable (Treat × Post). This variable takes the value of 1 for firms in the treatment group during the post-policy period, and 0 otherwise. |

| Moderating Variable | Entrepreneurial Green Attention | EGA | (Total word frequency of green attention vocabulary in the MD&A section/Total word frequency of the MD&A section) × 100 |

| Control Variables | Firm Size | Size | Natural logarithm of total assets at year-end |

| Asset–Liability Ratio | Lev | Total liabilities at year-end/Total assets at year-end | |

| Return on Total Assets | ROA | Net profit/Average balance of total assets | |

| Cash Flow Ratio | Cashflow | Net cash flow from operating activities/Total assets | |

| Operating Revenue Growth Rate | Growth | (Current year’s operating revenue/Previous year’s operating revenue) − 1 | |

| Board Size | Board | Natural logarithm of the number of board directors | |

| CEO Duality | Dual | Equals 1 if the Chairman and the General Manager are the same person, otherwise 0 | |

| Shareholding Ratio of the Largest Shareholder | Top1 | Number of shares held by the largest shareholder/Total number of shares | |

| Tobin’s Q | TobinQ | (Market value of tradable shares + Number of non-tradable shares × Net assets per share + Book value of liabilities)/Total assets | |

| Listing Age | ListAge | Ln(Current year − IPO year + 1) | |

| Economic Development Level | GDP | Logarithm of per capita GDP | |

| Financial Development Level | Finance | Balance of various loans from financial institutions at year-end/GDP | |

| Industrialization Level | GDP_two | Proportion of value-added of the secondary industry in GDP | |

| Degree of Government Intervention | Gov | Local fiscal expenditure/GDP |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GREEN | 11,250 | 0.033 | 0.044 | 0.005 | 0.411 |

| Pilot × Post | 11,250 | 0.130 | 0.336 | 0 | 1 |

| Size | 11,250 | 22.431 | 1.405 | 19.470 | 26.456 |

| Lev | 11,250 | 0.430 | 0.207 | 0.046 | 0.934 |

| ROA | 11,250 | 0.036 | 0.069 | −0.415 | 0.255 |

| Cashflow | 11,250 | 0.044 | 0.068 | −0.203 | 0.266 |

| TobinQ | 11,250 | 2.119 | 1.471 | 0.802 | 17.676 |

| Growth | 11,250 | 0.161 | 0.434 | −0.673 | 4.429 |

| Board | 11,250 | 2.111 | 0.202 | 1.609 | 2.708 |

| Dual | 11,250 | 0.292 | 0.454 | 0 | 1 |

| Top1 | 11,250 | 0.341 | 0.152 | 0.080 | 0.754 |

| ListAge | 11,250 | 2.239 | 0.791 | 0.693 | 3.401 |

| GDP | 11,250 | 11.710 | 0.453 | 9.799 | 13.056 |

| GDP_two | 11,250 | 32.570 | 10.509 | 15.83 | 67.45 |

| Finance | 11,250 | 5.219 | 1.577 | 1.185 | 8.777 |

| Gov | 11,250 | 0.180 | 0.046 | 0.081 | 0.312 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GREEN | GREEN | GREEN | |

| Pilot × Post | 0.0111 *** | 0.0136 *** | 0.0072 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Size | 0.0047 *** | 0.0042 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.001) | ||

| Lev | −0.0120 *** | −0.0051 | |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | ||

| ROA | 0.0044 | 0.0097 | |

| (0.007) | (0.008) | ||

| Cashflow | 0.0070 | −0.0054 | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| TobinQ | −0.0005 | 0.0001 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Growth | −0.0023 ** | −0.0020 *** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Board | −0.0011 | 0.0033 | |

| (0.002) | (0.004) | ||

| Dual | 0.0031 *** | 0.0019 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Top1 | −0.0097 *** | −0.0042 | |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | ||

| ListAge | −0.0070 *** | −0.0056 *** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| GDP | 0.0002 | −0.0000 | |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | ||

| GDP_two | −0.0004 *** | −0.0002 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Finance | −0.0029 *** | −0.0022 *** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Gov | −0.0256 ** | 0.0223 | |

| (0.011) | (0.019) | ||

| Constant | 0.0318 *** | −0.0161 | −0.0399 |

| (0.000) | (0.017) | (0.042) | |

| Observations | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 |

| R-squared | 0.007 | 0.037 | 0.099 |

| Controls | NO | YES | YES |

| Ind FE | NO | NO | YES |

| Year FE | NO | NO | YES |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage | Second Stage | |

| IV | 0.4893 ** | |

| (0.202) | ||

| Pilot × Post | 0.0246 ** | |

| (0.011) | ||

| Constant | −2.7742 *** | |

| (0.866) | ||

| Observations | 11,250 | 11,250 |

| R-squared | 0.481 | 0.008 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Policies | Special Period | Kernel Matching | Caliper Matching | 1:1 Nearest Neighbor Matching | |

| Pilot × Post | 0.0051 *** | 0.0080 *** | 0.0066 *** | 0.0071 *** | 0.0047 ** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Pilot × Post1 | 0.0010 | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| Pilot × Post2 | 0.0060 | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| Constant | 0.0055 | −0.0341 | −0.0514 | −0.0473 | −0.0529 ** |

| (0.019) | (0.039) | (0.048) | (0.050) | (0.021) | |

| Observations | 11,250 | 8474 | 10,960 | 10,300 | 2245 |

| R-squared | 0.100 | 0.103 | 0.098 | 0.100 | 0.136 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GREEN | CEDRT | GREEN | Reg_GreenInnov | GREEN | Media | GREEN | |

| Pilot × Post | 0.1922 *** | 0.0065 *** | 0.6502 * | 0.0063 *** | 0.1199 *** | 0.0068 *** | |

| (0.067) | (0.002) | (0.360) | (0.002) | (0.043) | (0.002) | ||

| c_DID | 0.0064 *** | ||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||

| c_EGA | −0.0011 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| c.DID × c.EGA | 0.0066 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| CEDRT | 0.0035 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| Region_innov | 0.0013 ** | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| Media | 0.0033 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| Constant | −0.0384 | −7.3562 *** | −0.0141 | −15.0238 ** | −0.0199 | −6.7846 *** | −0.0174 |

| (0.041) | (1.488) | (0.036) | (6.277) | (0.040) | (0.573) | (0.036) | |

| Observations | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 |

| R-squared | 0.101 | 0.304 | 0.110 | 0.690 | 0.100 | 0.461 | 0.103 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOE | Non-SOE | Heavily Polluting | Non-Heavily Polluting | Modern Urban | Resource-driven | High Env. Concern | Low Env. Concern | |

| Pilot × Post | 0.0012 | 0.0075 *** | 0.0012 | 0.0070 *** | 0.0067 ** | −0.0019 | 0.0091 *** | 0.0056 |

| (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.004) | |

| Constant | −0.0482 | −0.0259 | −0.0482 | −0.0199 | −0.0715 | 0.0824 | −0.0511 | −0.0344 |

| (0.060) | (0.022) | (0.060) | (0.022) | (0.058) | (0.079) | (0.046) | (0.042) | |

| Observations | 4357 | 6582 | 4357 | 6893 | 8653 | 2596 | 7309 | 3941 |

| R-squared | 0.126 | 0.100 | 0.126 | 0.097 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 0.104 | 0.100 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | 0.0012 | 0.0070 *** | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invention Patent Green Bubble | Utility Model Green Patent Bubble | Environmental Info. Disclosure Quality | |

| Pilot × Post | 0.0463 ** | −0.0096 | −0.0703 * |

| (0.020) | (0.016) | (0.041) | |

| Constant | −4.3525 *** | 0.2511 | −4.7242 *** |

| (1.503) | (0.183) | (0.470) | |

| Observations | 11,250 | 11,250 | 11,250 |

| R-squared | 0.069 | 0.002 | 0.413 |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Deng, S.; Pi, A. Sustainable Development Agenda Pilot Zones Policy, Entrepreneurial Green Attention and Corporate Green Development. Sustainability 2026, 18, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010418

Wang J, Zhao W, Deng S, Pi A. Sustainable Development Agenda Pilot Zones Policy, Entrepreneurial Green Attention and Corporate Green Development. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010418

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiahui, Weifeng Zhao, Siyuan Deng, and Aobo Pi. 2026. "Sustainable Development Agenda Pilot Zones Policy, Entrepreneurial Green Attention and Corporate Green Development" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010418

APA StyleWang, J., Zhao, W., Deng, S., & Pi, A. (2026). Sustainable Development Agenda Pilot Zones Policy, Entrepreneurial Green Attention and Corporate Green Development. Sustainability, 18(1), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010418