Constraints on Youth Participation in Evening Schools: Empirical Evidence from Shenyang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Intrapersonal Constraints, which encompass individual-level barriers such as time availability, financial resources, safety concerns, and self-efficacy perceptions;

- (2)

- Interpersonal Constraints, referring to participation limitations stemming from social factors such as family support and peer influence;

- (3)

- Structural Constraints, relating to objective supply-side conditions, including geographical location, transportation accessibility, and the adequacy of internal and external facilities;

- (4)

- Experiential Constraints, involving the impact of instructors’ professional competence, the alignment between course content and participant expectations, and other factors influencing continued engagement. It is important to clarify that within this model, teaching quality is operationalized and measured strictly through the subjective experiences and satisfaction levels reported by participants. It is not treated as an objective or systemic feature of service provision. This distinction serves to separate clearly between externally verifiable structural conditions and internally perceived experiential factors;

- (5)

- Attitudinal Perception, which focuses on examining how an individual’s subjective valuation of evening schools—such as perceptions of personal development, psychological and cultural leisure benefits, and social relationship building—not only directly affects participation behavior, but may also mediate or moderate the relationship between other constraint factors and participation.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Lens

2.1.1. A Literature Review on Leisure Constraints Theory

2.1.2. A Literature Review on the Theory of Planned Behavior

2.1.3. Key Model Components

- A.

- Intrapersonal Constraints

- B.

- Interpersonal Constraints

- C.

- Structural Constraints

- D.

- Experiential Constraints

- E.

- Attitudinal Perception

- F.

- Participation behavior

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Sample Selection Criteria

3.3. Questionnaire Design

3.4. Implementation

3.5. Analysis Techniques

4. Results

4.1. Respondents Characteristics

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Reliability Analysis

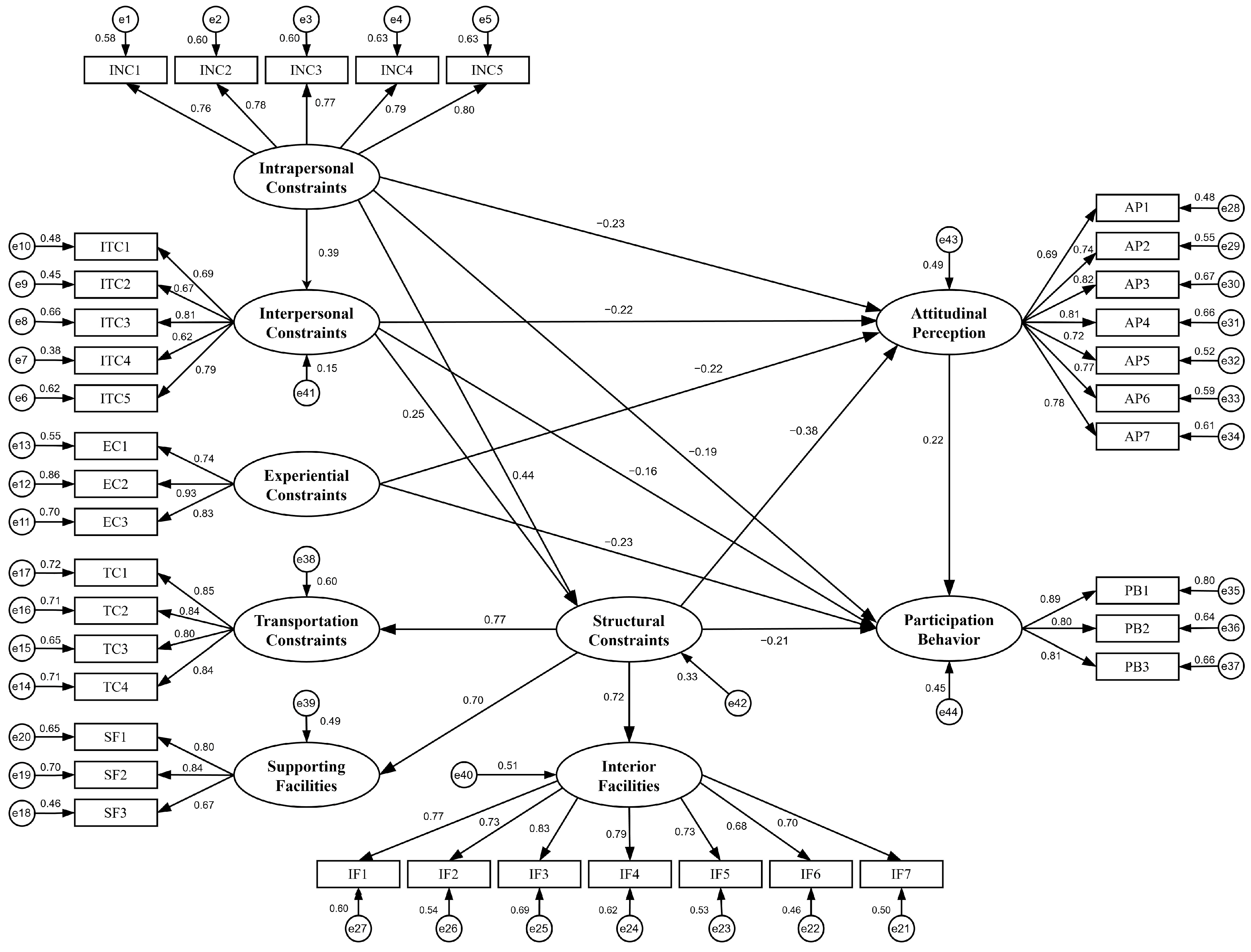

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lan, A. What makes evening school so appealing to young people? Pop. Trubune 2024, 40–42. Available online: https://paper.people.com.cn/rmlt/html/2024-07/15/content_26080728.htm (accessed on 10 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Communist Youth League of China. A Historical Review of “Evening Schools” and Reflections on Establishing Youth Evening Schools; Communist Youth League of China: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 53–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, C. Youth Evening School—Illuminating Trendy “Eveninglife”. Chongqing CPPCC News, 9 May 2024; p. 004, (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiwei, P.; Siyi, Y. Youth Evening School Launches a New “Evening” for Young People. Changde Daily, 13 June 2024; p. 003, (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongzgou, H. Innovating the Youth Evening School Model to Build a New Engine for Guiding Youth Ideology; Communist Youth League of China: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 30–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin-ying, S.; Lan, L.; Yan, Q.; Pingping, W. Characteristics and prospect of foreign leisure constraints research: Based on the literature analysis of Journal of Leisure Research, Leisure Sciences, and Journal of Park and Recreation Administration. J. Subtrop. Resour. Environ. 2014, 9, 35–44, 95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D.W.; Godbey, G. Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leis. Sci. 1987, 9, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L. Toward an understanding of the constraints on leisure. J. Leis. Res. 1991, 23, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D.W.; Godbey, G.; Jackson, E.L. A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannell, R.C.; Kleiber, D.A. A Social Psychology of Leisure; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Su, X.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, C. Exploration of Leisure Constraints Perception in the Context of a Pandemic: An Empirical Study of the Macau Light Festival. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 822208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, K.; Karagiorgos, T.; Ntovoli, A.; Zourladani, S. Using the Theories of Planned Behaviour and Leisure Constraints to Study Fitness Club Members’ Behaviour after COVID-19 Lockdown. Leis. Stud. 2022, 41, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humagain, P.; Singleton, P.A. Exploring Tourists’ Motivations, Constraints, and Negotiations Regarding Outdoor Recreation Trips during COVID-19 through a Focus Group Study. J. Outdo. Recreat. Tour. Res. Plan. 2021, 36, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Floyd, C.; Kim, A.C.H.; Baker, B.J.; Sato, M.; James, J.D.; Funk, D.C. To Be or Not to Be: Negotiating Leisure Constraints with Technology and Data Analytics amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodolska, M.; Shinew, K.J.; Camarillo, L.N. Constraints on Recreation Among People of Color: Toward a New Constraints Model. Leis. Sci. 2020, 42, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.; Mcneil, N.; Seal, E.-L.; Nicholson, M. Understanding the Constraints Shaping Women’s Intentions to Stop Playing Community Sport. Leis. Sci. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, G.; Dilmaç, E. Leisure Behavior Through the Life Span: Leisure Constraints, Motivation, and Self-Efficacy Among Gen Z and Millennials. Loisir Et Société/Soc. Leis. 2024, 47, 439–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Huang, M.; Li, C.-L.; Xu, B. Leisure Constraint and Mental Health: The Case of Park Users in Ningbo, China. J. Outdo. Recreat. Tour. Res. Plan. 2022, 39, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1988; pp. 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M. An investigation of the relationships between beliefs about an object and the attitude toward that object. Hum. Relat. 1963, 16, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison–Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W.; Jiang, G. A review of the theory of planned behavior. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 16, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analytic Review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEachan, R.R.C.; Conner, M.; Taylor, N.J.; Lawton, R.J. Prospective Prediction of Health-Related Behaviours with the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 97–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention—Behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and Intention in Everyday Life: The Multiple Processes by Which Past Behavior Predicts Future Behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, P.M.; Sheeran, P. Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of Effects and Processes. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press Inc: San Diego, CA, USA, 2006; Volume 38, pp. 69–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Ling, J.; Zahry, N.R.; Liu, C.; Ammigan, R.; Kaur, L. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Determine COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions and Behavior among International and Domestic College Students in the United States. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0293130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K. COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions: The Theory of Planned Behavior, Optimistic Bias, and Anticipated Regret. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, L. Predicting Intention to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine among the General Population Using the Health Belief Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior Model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, B.K. SEM Approach for TPB: Application to Digital Health Software and Self-Health Management. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–17 December 2017; Arabnia, H.R., Deligiannidis, L., Tinetti, F.G., Tran, Q.N., Yang, M.Q., Eds.; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1660–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, J.A.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Kim, S.J.; McHugo, G.J.; Unutzer, J.; Bartels, S.J.; Marsch, L.A. Health Behavior Models for Informing Digital Technology Interventions for Individuals with Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2017, 40, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braksiek, M.; Thormann, T.F.; Wicker, P. Intentions of environmentally friendly behavior among sports club members: An empirical test of the theory of planned behavior across genders and sports. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 657183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, J.; Jang, D. Climate Change Awareness and Pro-Environmental Intentions in Sports Fans: Applying the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Sustainable Spectating. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Won, D.; Jeon, H.S. Predictors of Sports Gambling among College Students: The Role of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Problem Gambling Severity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Kang, S.-W. An Analysis of the Relationship between the Modified Theory of Planned Behavior and Leisure Rumination of Korean Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Huangfu, X. The More Training, the More Willingness? A Positive Spillover Effect Analysis of Voluntary Behavior in Environmental Protection. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Damaneh, H.E.; Damaneh, H.E.; Cotton, M. Integrating the Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behaviour to Investigate Farmer Pro-Environmental Behavioural Intention. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Hudson, S. Tourism Demand Constraints—A Skiing Participation. Ann. Touris. Res. 2000, 27, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Emerging Bicycle Tourism and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.-B.; Ho, C.-H. Leisure Constraints and Participant Intention among Vietnamese Migrant Laborers in Taiwan: The Role of Leisure Motivation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation. J. Leis. Res. 2025, 56, 822–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tian, Y.; Xia, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. When Technology Meets Heritage: A Moderated Mediation of Immersive Technology on the Constraint-Satisfaction Relationship. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 632–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L.; Crawford, D.W.; Godbey, G. Negotiation of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1993, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J.; Mannell, R.C. Testing Competing Models of the Leisure Constraint Negotiation Process in a Corporate Employee Recreation Setting. Leis. Sci. 2001, 23, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.D. A Structural Model of Leisure Constraints Negotiation in Outdoor Recreation. Leis. Sci. 2008, 30, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, K.B.; Hemmings-Jarrett, K.; Elangovan, S. Negotiating equitable metaleisure participation: Developing a theoretical framework for Gen Z’s constraint navigation in the metaverse. World Leis. J. 2025, 67, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, D.; Johnson, B.T.; Fishbein, M.; Muellerleile, P.A. Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior as Models of Condom Use: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Moeser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Interaction of Domestic Tourists’ Travel Needs and Behavior: Empirical Research on Travel Career Pattern, Perceived Constraints, Attitude, and Revisit Intention. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Kun, W. Middle-Aged Group Leisure Sports in Shanxi Limiting Factors Characteristics and Its Relationship with Behavior Research. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi Normal University, Taiyuan, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. A Study on the Behavior Mechanism of Leisure Physical Exercise of the Elderly—The Construction of the Intermediary Effect Model of Leisure Restriction. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Study on the Restrictive Factors of Women’s Participation Inmarathon in Taiyuan—Take the 2019 TaiyuanInternational Marathon as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. Study on Influencing Factors of Outdoor Sports Tourism of College Students in Shanghai from the perspective of Leisure Restriction Theory. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y. A Study on the Constraint Factors and Strategies of Shanghai University Students Participate in Floorball. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L. Research on the Influence Mechanism of College Students’ Participation in Ice and Snow Sports Tourism in Changchun from the Perspective of Leisure Constraint Theory. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Sport University, Changchun, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J. Influence of Motivation and Constraints on Behavioral Intentions of Amateur Sailing Event Participants. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai University of Sport, Shanghai, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, X. The impact of urban social adaptability on new urban residents’ leisure constraints: A case study of Guangzhou. Urban Probl. 2018, 97–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institution Type | Institution Name | Daytime Function | Service Area | Core Features | Representative Courses | Evening School Operations Hours | Daily Average Foot Traffic | Fee Standard | Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Cultural Venues (Government-led) | Institution A | Senior University, Office | 2.5 km | Government funding and resource support; professional instructors; curriculum emphasizes traditional culture and foundational skills; affordable pricing; substantial foot traffic. | Tai Chi, Baduanjin, Vocal Music, Yoga, Classical Dance, Chinese Painting, Peking Opera, Street Dance, Guzheng, Photography, etc. | Tuesdays and Fridays, 7:00 PM–8:30 PM | Approx. 100 participants | ¥500/12 sessions | Heping District, Shenyang |

| Public Cultural Venue (Government-led) | Institution B | Children’s Training, Office Space | 2.5 km | Similar public cultural resource allocation; Primarily traditional culture and skill-based courses; Stable foot traffic. | Gu Zheng, Digital Piano, Ballet Posture, Classical Dance, Intangible Cultural Heritage, Paper-cutting, Stage Performance, Recitation, etc. | Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays 7:00 PM–8:30 PM | Approximately 60 participants | ¥500/12 sessions | Heping District, Shenyang |

| Commercial District Embedded (Independently Operated by Enterprise) | Institution C | Bookstore Operations | 1.5 km | Courses are innovative and trendy, with a comfortable environment; they offer a mixed-use concept (shopping/reading/learning), but pricing is on the high side. | Coffee latte art, short video editing, business planning, lifestyle photography, voice training, entrepreneurship salons, etc. | Daily 6:30 PM–8:30 PM | Approx. 45 participants | Variable pricing (average ¥400/6 sessions) | Heping District, Shenyang |

| Community-based (independently operated by the enterprise) | Institution D | Senior University | 1 km | Excellent community accessibility; currently in trial operation phase with low foot traffic and affordable pricing | Gu Zheng, Piano, Vocal Music, Fitness, Softball, Yoga, Modeling, etc. | Daily 7:00 PM–8:30 PM | Approx. 10 participants | ¥500/12 sessions | Hunnan District, Shenyang |

| Measures | Factor Loadings | Item-Total Correlation | Mean (S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intrapersonal Constraints (α = 0.89) | |||

| I don’t have free time to attend evening school. (INC1) | 0.71 | 0.71 | 2.67 (1.08) |

| I consider attending evening school to be too wasteful of money. (INC2) | 0.73 | 0.72 | 2.60 (1.13) |

| I’m concerned about safety issues after attending evening school. (INC3) | 0.73 | 0.71 | 2.54 (1.05) |

| My own abilities (such as my capacity to absorb new knowledge or handle pressure) prevent me from attending evening school. (INC4) | 0.77 | 0.73 | 2.40 (1.14) |

| My physical condition prevents me from attending evening school. (INC5) | 0.80 | 0.74 | 2.18 (1.07) |

| 2. Interpersonal Constraints (α = 0.84) | |||

| My friends (family or colleagues) have different interests than I do. (ITC1) | 0.74 | 0.62 | 3.01 (1.05) |

| I cannot find suitable companions to attend evening school with. (ITC2) | 0.74 | 0.62 | 2.98 (1.16) |

| No one around me is interested in evening school. (ITC3) | 0.80 | 0.71 | 3.02 (1.02) |

| My peers’ free time doesn’t align with mine. (ITC4) | 0.72 | 0.59 | 2.97 (1.09) |

| No one can tell us how to attend evening school. (ITC5) | 0.73 | 0.68 | 3.25 (1.16) |

| 3. Structural Constraints | |||

| 3.1 Transportation Constraints (α = 0.90) | |||

| Distance from evening school to bus stops, subway stations, etc. (TC1) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 2.99 (1.16) |

| Uneven distribution and insufficient number of shared bicycle and electric scooter stations around the evening school. (TC2) | 0.78 | 0.78 | 3.11 (1.16) |

| Poor walkability around evening schools. (TC3) | 0.81 | 0.77 | 3.13 (1.05) |

| Poor location and insufficient number of parking lots around evening school. (TC4) | 0.77 | 0.79 | 3.28 (1.16) |

| 3.2 Supporting Facilities (α = 0.82) | |||

| Lack of commercial amenities around the evening school. (SF1) | 0.75 | 0.67 | 2.88 (1.19) |

| Lack of dining options near the evening school. (SF2) | 0.78 | 0.72 | 2.96 (1.22) |

| Lack of recreational and entertainment facilities near evening schools. (SF3) | 0.76 | 0.60 | 3.09 (1.17) |

| 3.3 Interior Facilities (α = 0.90) | |||

| The internal environment of the evening school (noise reduction, greening, etc.) is average. (IF1) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 3.06 (1.18) |

| Spatial functionality (recreational, social spaces, etc.) is limited. (IF2) | 0.72 | 0.68 | 3.12 (1.16) |

| Poor spatial hygiene and cleanliness. (IF3) | 0.79 | 0.77 | 3.21 (1.26) |

| Insufficient quantity and poor quality of space facilities and equipment (lighting, desks/chairs, musical instruments, etc.). (IF4) | 0.80 | 0.75 | 3.11 (1.21) |

| Insufficient number of restrooms and changing rooms. (IF5) | 0.73 | 0.69 | 3.02 (1.22) |

| Insufficient storage facilities. (IF6) | 0.71 | 0.65 | 3.11 (1.14) |

| Poor classroom soundproofing. (IF7) | 0.80 | 0.69 | 3.13 (1.19) |

| 4. Experiential Constraints (α = 0.87) | |||

| I am dissatisfied with the instructor. (EC1) | 0.83 | 0.70 | 2.60 (1.13) |

| Did not experience enjoyment during participation. (EC2) | 0.76 | 0.81 | 2.77 (1.20) |

| During participation, the expected goals were not achieved. (EC3) | 0.77 | 0.76 | 2.71 (1.16) |

| 5. Attitudinal Perception (α = 0.92) | |||

| I believe participating in evening school is a worthwhile activity. (AP1) | 0.74 | 0.69 | 4.04 (1.00) |

| I believe attending evening school is to satisfy personal interests and hobbies as well as the need for personalized development. (AP2) | 0.72 | 0.73 | 4.09 (0.93) |

| I believe attending evening school serves as a form of relaxation and a way to relieve work and life pressures. (AP3) | 0.73 | 0.79 | 3.80 (1.12) |

| I believe attending evening school is for creating leisure and entertainment, enriching my cultural life outside of work. (AP4) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 3.91 (1.04) |

| I believe attending evening school is for making friends, interacting with peers, and improving social skills. (AP5) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 3.80 (1.09) |

| I believe attending evening school is to improve and demonstrate my learning skills. (AP6) | 0.76 | 0.75 | 3.80 (1.06) |

| I believe attending evening school is to foster a healthy lifestyle environment with family (friends, colleagues). (AP7) | 0.78 | 0.77 | 3.64 (1.14) |

| 6. Participation behavior (α = 0.89) | |||

| I will continue to participate in evening school actively. (PB1) | 0.76 | 0.82 | 3.43 (1.07) |

| I will be able to overcome difficulties and distractions to continue attending evening school in the future. (PB2) | 0.77 | 0.76 | 3.40 (1.08) |

| I will actively recommend people around me to participate in evening school. (PB3) | 0.73 | 0.77 | 3.28 (1.07) |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 95 | 44.2 |

| Female | 120 | 55.8 | |

| Age Group | Under 18 | 2 | 0.93 |

| 18–25 years old | 71 | 33.02 | |

| 26–30 years old | 74 | 34.42 | |

| 31–40 years old | 39 | 18.14 | |

| Over 40 years old | 29 | 13.49 | |

| Occupation | Government/Institution Staff | 42 | 19.53 |

| Corporate Employee | 61 | 28.37 | |

| Young Freelancer | 21 | 9.77 | |

| Young Self-Employed | 23 | 10.70 | |

| Young Unemployed/Job-seeking | 15 | 6.98 | |

| Students | 32 | 14.88 | |

| Others | 21 | 9.77 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 163 | 75.8 |

| Married without children | 12 | 5.6 | |

| Married with children | 38 | 17.7 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Widowed | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Education Level | Junior High School or Lower | 2 | 0.9 |

| Senior High School/Vocational School | 12 | 5.6 | |

| Associate/Bachelor’s Degree | 155 | 72.1 | |

| Master’s Degree or Higher | 46 | 21.4 | |

| Need for Evening School | No Need | 20 | 9.3 |

| Minimal Need | 38 | 17.7 | |

| Moderate Need | 66 | 30.7 | |

| Considerable Need | 36 | 16.7 | |

| Extreme Need | 55 | 25.6 |

| Indicator | Reference Standard | Observed Value |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | 1–3: Excellent, 3–5: Good | 1.424 |

| RMSEA | <0.05 is excellent, <0.08 is good | 0.045 |

| IFI | >0.9 is excellent, >0.8 is good | 0.948 |

| TLI | >0.9 is excellent, >0.9 is good | 0.942 |

| CFI | >0.9 is excellent, >0.10 is good | 0.948 |

| Dimension | Measurement Item | Construct Loadings | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Explained (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal Constraints | INC1 | 0.77 (***) | 0.89 | 0.61 |

| INC2 | 0.79 (***) | |||

| INC3 | 0.77 (***) | |||

| INC4 | 0.79 (***) | |||

| INC5 | 0.79 (***) | |||

| Interpersonal Constraints | ITC1 | 0.69 (***) | 0.84 | 0.52 |

| ITC2 | 0.67 (***) | |||

| ITC3 | 0.81 (***) | |||

| ITC4 | 0.62 (***) | |||

| ITC5 | 0.79 (***) | |||

| Transportation Constraints | TC1 | 0.85 (***) | 0.90 | 0.70 |

| TC2 | 0.84 (***) | |||

| TC3 | 0.80 (***) | |||

| TC4 | 0.85 (***) | |||

| Supporting Facilities | SF1 | 0.78 (***) | 0.82 | 0.60 |

| SF2 | 0.87 (***) | |||

| SF3 | 0.67 (***) | |||

| Interior Facilities | IF1 | 0.77 (***) | 0.90 | 0.56 |

| IF2 | 0.73 (***) | |||

| IF3 | 0.83 (***) | |||

| IF4 | 0.79 (***) | |||

| IF5 | 0.73 (***) | |||

| IF6 | 0.68 (***) | |||

| IF7 | 0.71 (***) | |||

| Experiential Constraints | EC1 | 0.73 (***) | 0.87 | 0.70 |

| EC2 | 0.93 (***) | |||

| EC3 | 0.83 (***) | |||

| Attitudinal Perception | AP1 | 0.72 (***) | 0.92 | 0.62 |

| AP2 | 0.76 (***) | |||

| AP3 | 0.84 (***) | |||

| AP4 | 0.83 (***) | |||

| AP5 | 0.75 (***) | |||

| AP6 | 0.79 (***) | |||

| AP7 | 0.80 (***) | |||

| Participation Behavior | PB1 | 0.91 (***) | 0.89 | 0.73 |

| PB2 | 0.82 (***) | |||

| PB3 | 0.84 (***) |

| Dimension | Intrapersonal Constraints | Interpersonal Constraints | Transportation Constraints | Supporting Facilities | Interior Facilities | Experiential Constraints | Attitudinal Perception | Participation Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal Constraints | 0.61 | |||||||

| Interpersonal Constraints | 0.39 | 0.52 | ||||||

| Transportation constraints | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.70 | |||||

| Supporting Facilities | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.60 | ||||

| Interior Facilities | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.56 | |||

| Experiential Constraints | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.70 | ||

| Attitudinal perception | −0.59 | −0.51 | −0.54 | −0.47 | −0.39 | −0.56 | 0.62 | |

| Participation Behavior | −0.58 | −0.49 | −0.43 | −0.49 | −0.38 | −0.57 | 0.63 | 0.73 |

| Square root of AVE | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.85 |

| Path | Path Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Intrapersonal Constraints → Participation Behavior | −0.19 (*) | 0.09 | −2.27 | Accepted |

| H1b: Interpersonal Constraints → Participation Behavior | −0.16 (*) | 0.08 | −2.13 | Accepted |

| H1c: Structural Constraints → Participation Behavior | −0.23 (*) | 0.12 | −2.05 | Accepted |

| H1d: Experiential Constraints → Participation Behavior | −0.21 (***) | 0.06 | −3.56 | Accepted |

| H1e: Attitudinal Perception → Participation Behavior | 0.22 (*) | 0.13 | 2.26 | Accepted |

| H2a: Intrapersonal Constraints → Attitudinal Perception | −0.23 (**) | 0.07 | −2.78 | Accepted |

| H2b: Interpersonal Constraints → Attitudinal Perception | −0.22 (*) | 0.05 | −2.92 | Accepted |

| H2c: Structural Constraints → Attitudinal Perception | −0.38 (***) | 0.04 | −3.56 | Accepted |

| H2d: Experiential Constraints → Attitudinal Perception | −0.22 (***) | 0.09 | −3.86 | Accepted |

| H4: Intrapersonal Constraints → Interpersonal Constraints | 0.39 (***) | 0.07 | 4.89 | Accepted |

| H5: Intrapersonal Constraints → Structural Constraints | 0.44 (***) | 0.09 | 4.69 | Accepted |

| H6: Interpersonal Constraints → Structural Constraints | 0.25 (**) | 0.07 | 2.80 | Accepted |

| Path | Effect Size | Relative Effect Size | Mediation Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation Effect | Direct Effect | Total Effect | Mediation Effect | p | |

| H3a: Intrapersonal Constraints → Attitudinal Perception → Participation Behavior | −0.05 | −0.20 | −0.26 | 20.39% | 0.03 |

| H3b: Interpersonal Constraints → Attitudinal Perception → Participation Behavior | −0.05 | −0.16 | −0.20 | 22.06% | 0.04 |

| H3c: Structural Constraints → Attitudinal Perception → Participation Behavior | −0.10 | −0.25 | −0.35 | 27.83% | 0.02 |

| H3d: Experiential Constraints → Attitudinal Perception → Participation Behavior | −0.04 | −0.22 | −0.26 | 16.92% | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Ye, R.; Dou, C.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Constraints on Youth Participation in Evening Schools: Empirical Evidence from Shenyang, China. Sustainability 2026, 18, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010413

Li S, Ye R, Dou C, Li J, Yang J. Constraints on Youth Participation in Evening Schools: Empirical Evidence from Shenyang, China. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010413

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shasha, Rensong Ye, Chenxi Dou, Jiayi Li, and Jiayu Yang. 2026. "Constraints on Youth Participation in Evening Schools: Empirical Evidence from Shenyang, China" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010413

APA StyleLi, S., Ye, R., Dou, C., Li, J., & Yang, J. (2026). Constraints on Youth Participation in Evening Schools: Empirical Evidence from Shenyang, China. Sustainability, 18(1), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010413