Land Use and Nature-Based Climate Adaptation in Coastal and Island Regions: A Case Study of Muan and Shinan, South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

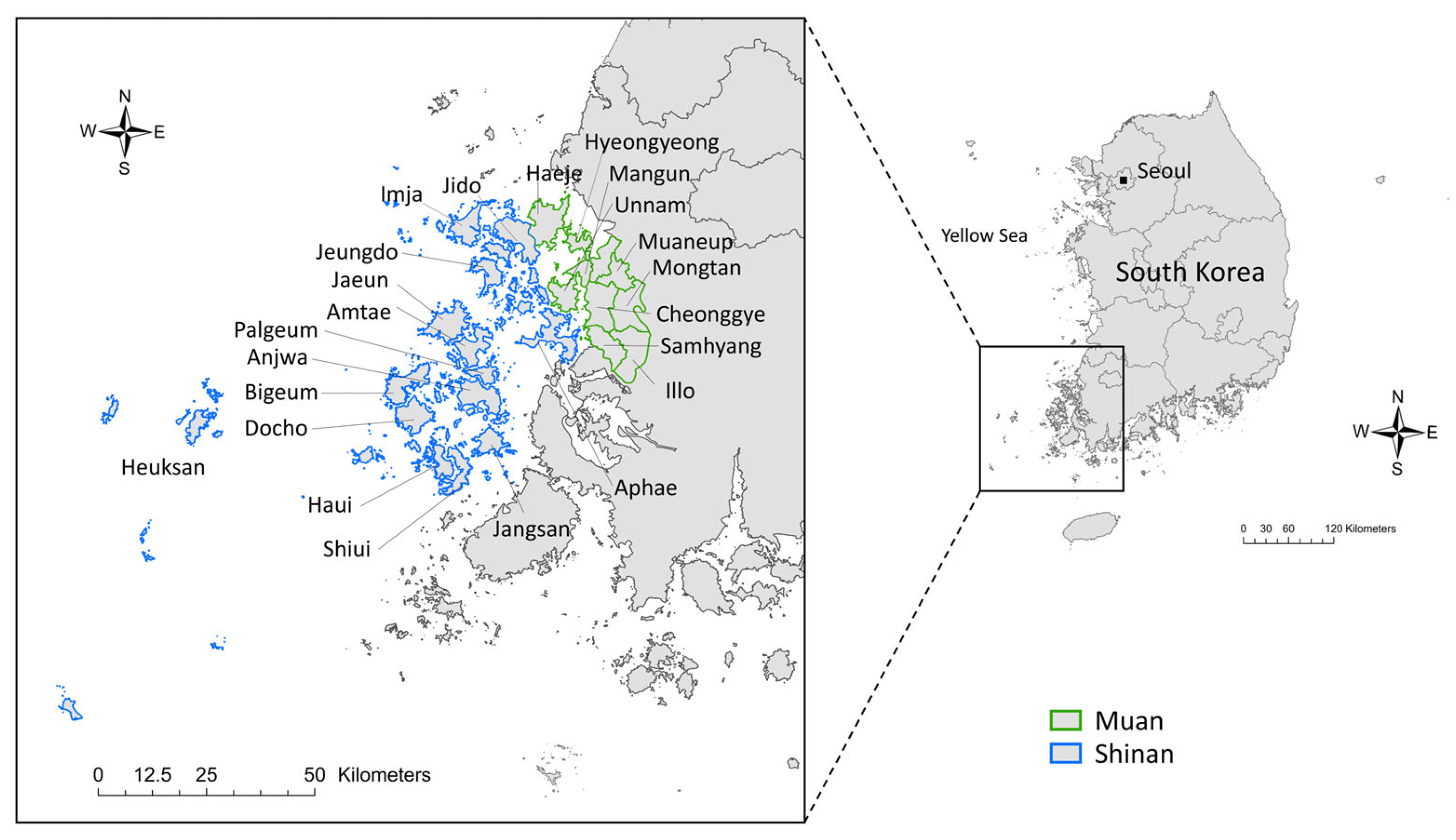

2. Study Areas

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Land Use and Climate Data

3.2. Correlation Analysis

4. Results

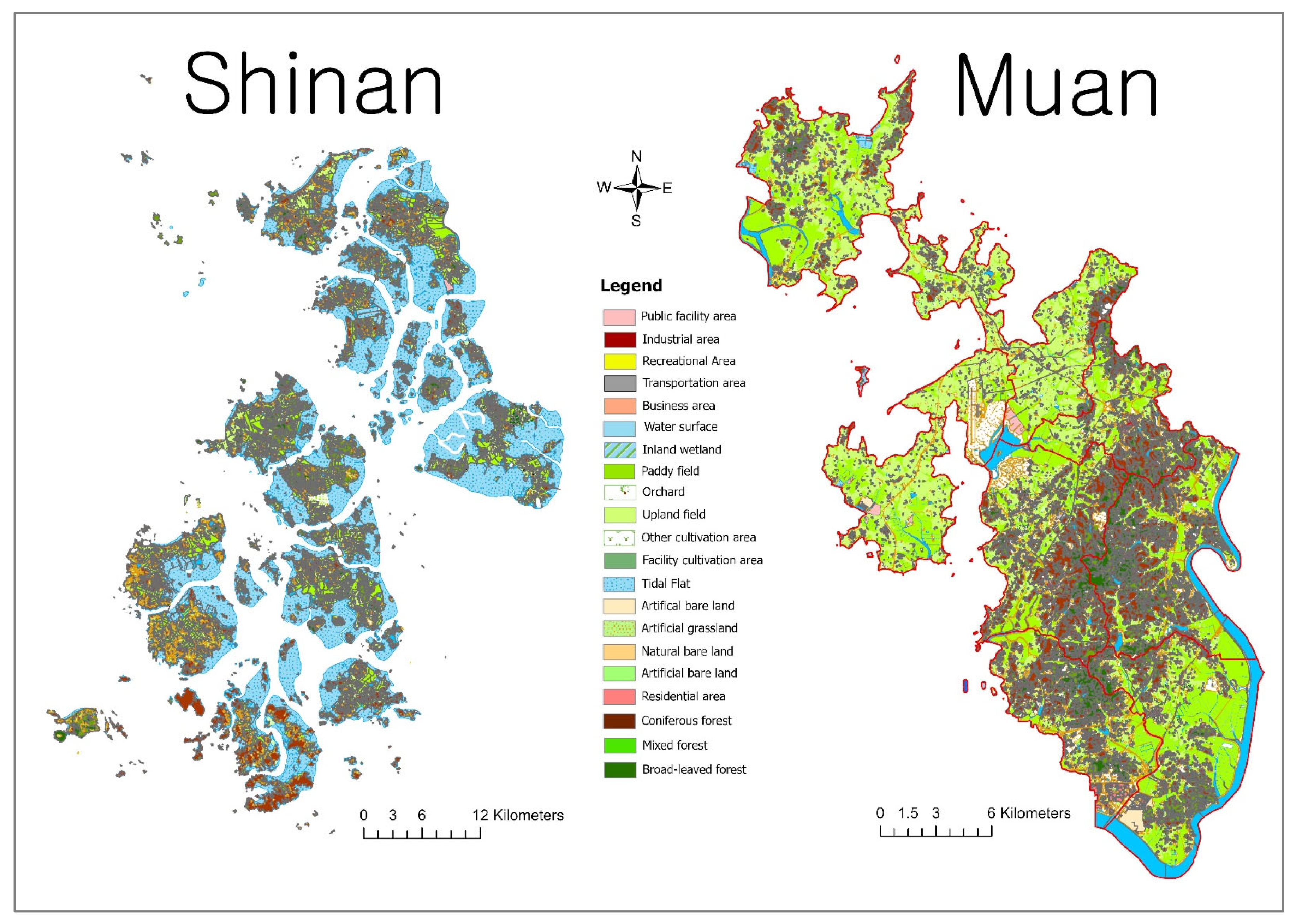

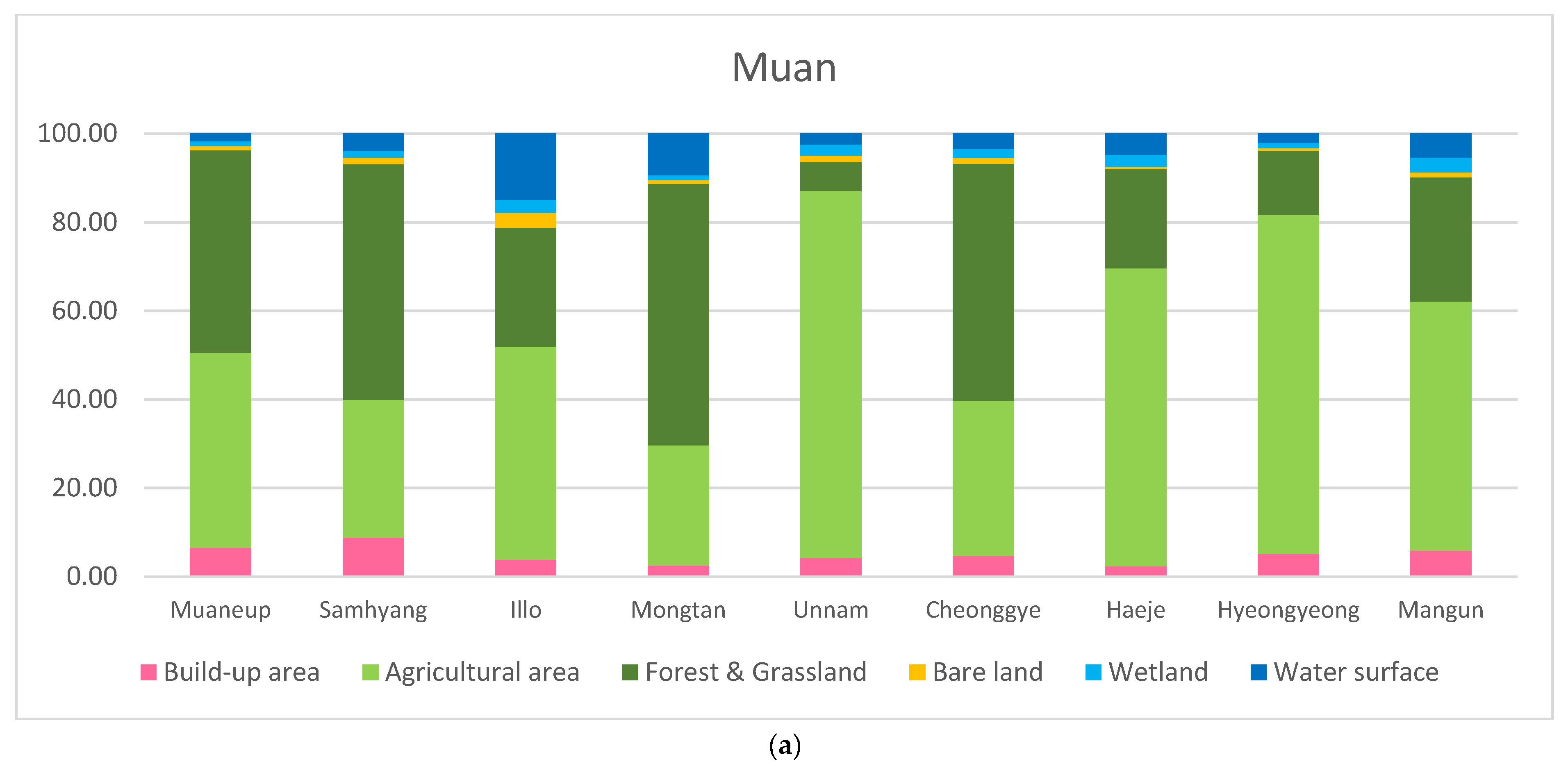

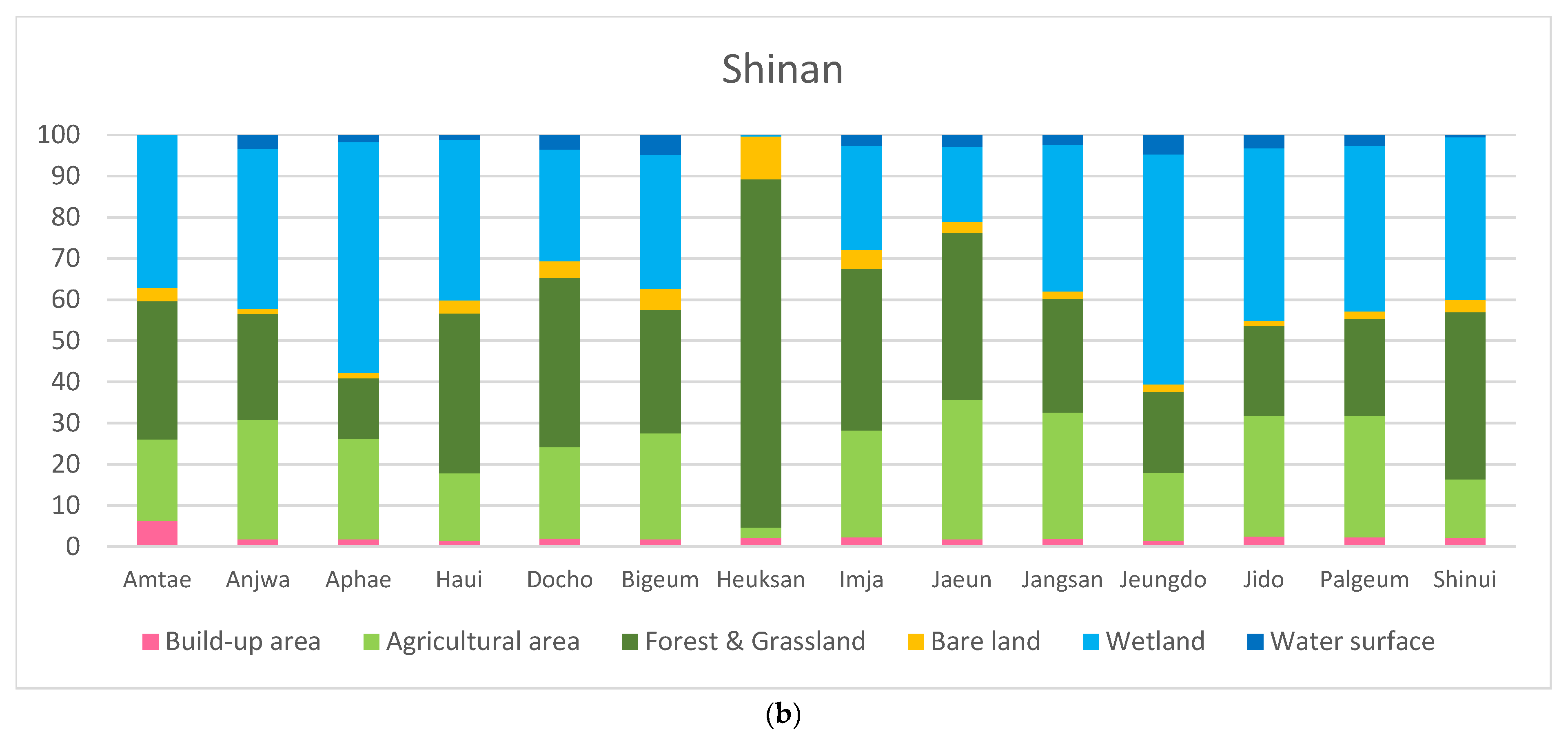

4.1. Land Use

4.2. Correlations Between Land Use and Climate

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griggs, G.; Reguero, B.G. Coastal adaptation to climate change and sea-level rise. Water 2021, 13, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N.; Babu, M.S.U.; Nautiyal, S. Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise: A Review of Studies on Low-Lying and Island Countries; ISEC Working Paper; Institute for Social and Economic Change: Bangalore, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Liu, B.; Lu, X. Effects of land use/land cover on diurnal temperature range in the temperate grassland region of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barati, A.A.; Zhoolideh, M.; Azadi, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Scheffran, J. Interactions of land-use cover and climate change at global level: How to mitigate the environmental risks and warming effects. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Small islands. In Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; McCarthy, J.J., Canziani, O.F., Leary, N.A., Dokken, D.J., White, K.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Singapore, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pielke, A.R.; Pitman, A.; Niyogi, D.; Mahmood, R.; Mcalpine, C.; Hossain, F.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Nair, U.; Betts, R.; Fall, S.; et al. Land use/land cover changes and climate: Modeling analysis and observational evidence. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2011, 2, 828–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; Briggs, J.M. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 2008, 319, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Defries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L., II; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelsson, J.; Turner, G.; Reynolds, N.; Umeh, E.; Kovats, S.; Murage, P.; Hands, A. Are local authority green infrastructure strategies in England addressing climate and environmental risks to public health? A policy review. Nat. Based Solut. 2026, 9, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspective on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-C.; Kim, D.-G. A Study on Correlations between Sea Surface Temperature and Air-Temperature of The Yellow Sea of Korea. J. Korean Isl. 2018, 30, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Choi, Y.; Moon, J.-Y.; Yun, W.-T. Classification of Climate Zones in South Korea Considering both Air Temperature and Rainfall. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2009, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, S.; Esteban, M.; Albert, S.; Jamero, M.L.; Crichton, R.; Heck, N.; Goby, G.; Jupiter, S. Local adaptation responses to coastal hazards in small island communities: Insights from 4 Pacific nations. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etongo, D.; Arriso, L. Vulnerability of fishery-based livelihoods to climate variability and change in a tropical island: Insights from small-scale fishers in Seychelles. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K. Korea’s Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change. Korea Environ. Policy Bull. 2011, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA). Annual Climate Report 2022; KMA: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.-W.; Lee, C.-G.; Chang, M.; Park, D.-S. Regional characteristics of hot days and tropical nights in the Honam area, South Korea. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2022, 23, e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.; Lee, M.-I. Spatial Variability and Long-Term Trend in the Occurrence Frequency of Heatwave and Tropical Night in Korea. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 55, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, G.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, T.-W.; Park, M.; Kwon, H.-H. Spatial and temporal variations in temperature and precipitation trends in South Korea over the past half-century (1974–2023) using innovative trend analysis. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2025, 58, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kang, S.-L. Non-stationary temperature extremes in South Korea: An extreme value analysis of global warming impacts. Atmos. Res. 2026, 328, 108388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Park, J.; Jang, D.H. Compound impact of heatwaves on vulnerable groups considering age, income, and disability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, A.B.; Kang, J. Assessing climate change impacts on flood risk in the Yeongsan River Basin, South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, K.J.; Yun, K.S. Climate change effects on tropical night days in Seoul, Korea. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 109, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-K.; Grydehøj, A. Sustainable Island Communities and Fishing Villages in South Korea: Challenges, Opportunities and Limitations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Cho, K.-M.; Hong, S.-K.; Kim, J.-E.; Kim, K.-W.; Lee, K.-A.; Moon, K.-O. Management plan for UNESCO Shinan Dadohae Biosphere Reserve (SDBR), Republic of Korea: Integrative perspective on ecosystem and human resources. J. Ecol. Environ. 2010, 33, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-E. Rural landscape and biocultural diversity in Shinan-gun, Jeollanam-do, Korea. J. Ecol. Environ. 2015, 38, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-E. Land use patterns and landscape structures on the islands in Jeonnam Province’s Shinan County occasioned by the construction of mainland bridges. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2016, 5, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, S. Ecosystem service relationships: Formation and recommended approaches from a systematic review. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 99, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.M.; Peterson, G.D.; Gordon, L.J. Understanding relationships among multiple ecosystem services. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Shu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Su, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, K.; Sun, S.; Liu, G. Quantifying impact of climate and land use changes on ecosystem services from statistic perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 172, 113285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L.; Sirois, M.J. Spearman correlation coefficients, differences between. In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bolboaca, S.D.; Jäntschi, L. Pearson versus Spearman, Kendall’s tau correlation analysis on structure-activity relationships of biologic active compounds. Leonardo J. Sci. 2006, 5, 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- De Lotto, R.; Bellati, R.; Moretti, M. Correlation methodologies between land use and greenhouse gas emissions: The coase of Pavia Province (Italy). Air 2024, 2, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-H.; Song, B.-G.; Park, J.-E. Analysis on the effects of land cover types and topographic features on heat wave days. J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Inf. Stud. 2016, 19, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS). Year-by-Year Data on Cultivated Land Area for Each Region of the Republic of Korea Are Available. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?sso=ok&returnurl=https%3A%2F%2Fkosis.kr%3A443%2FstatHtml%2FstatHtml.do%3FtblId%3DDT_1EB002%26orgId%3D101%26 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Abdolghafoorian, A.; Farhadi, L.; Bateni, S.M.; Margulis, S.; Xu, T. Characterizing the effect of vegetation dynamics on the bulk heat transfer coefficient to improve variational estimation of surface turbulent fluxes. J. Hydrometeorol. 2017, 18, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tian, F.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Z. Attribution of the land surface temperature response to land-use conversions from bare land. Glob. Planet. Change 2020, 193, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, R. Dynamics and interactions of soil moisture and temperature during degradation and restoration of alpine swamp meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1476167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, F.; Sassenou, L.-N.; Olivieri, L. Potential of Nature-Based Solutions to Diminish Urban Heat Island Effects and Improve Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Summer: Case Study of Matadero Madrid. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Sun, R.; Wu, Z.; Chen, B.; Yang, C.; Li, Q.; Fraedrich, K. Streamflow Response to Climate and Land-Use Changes in a Tropical Island Basin. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-E.; Hong, S.-K. Pattern and process in Maeul, a traditional Korean rural landscape. J. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 34, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-O.; Lee, W.; Kim, H.; Cho, Y. Social isolation and vulnerability to heatwave-related mortality in the urban elderly population: A time-series multi-community study in Korea. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marando, F.; Heris, M.P.; Zulian, G.; Udias, A.; Mentaschi, L.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Parastatidis, D.; Maes, J. Urban heat island mitigation by green infrastructure in European Functional Urban Areas. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting cities for climate change: The role of the green infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Muan | Shinan |

|---|---|---|

| Area | 436.40 km2 | 655.68 km2 |

| The scale of local residents (2020) | 86,132 persons | 38,938 persons |

| Population density | 197 persons/km2 | 59 persons/km2 |

| Economy | Mainly agriculture; limited aquaculture | Mixed farming, fishing, and aquaculture |

| Administrative units | 3 eups and 6 myeons (9 local offices) | 2 eups and 12 myeons (14 local offices) |

| Natural environment | Muan Tidal Flat Wetland Protected Area | UNESCO World Heritage (Getbol), UNESCO Shinan-Dadohae Biosphere Reserve, Dadohaehaesang National Park |

| Geographical features | North–south elongated terrain; most hills 200–300 m above sea level; extensive reclaimed tidal flats converted to cropland since the 1960s | 2 eups and 12 myeons (14 local offices) Composed of ~890 islands; mostly rolling hills 200–300 m above sea level; broad tidal flats |

| Category | Sub-Category |

|---|---|

| Build-up Area | Residential area |

| Business area | |

| Transportation area | |

| Institutional area | |

| Industrial area | |

| Recreational area | |

| Agricultural Area | Paddy fields |

| Upland fields | |

| Greenhouse cultivation area | |

| Other cultivation area | |

| Orchard | |

| Wetland | Tidal flats |

| Inland wetland | |

| Bare Land | Natural bare land |

| Artificial bare land | |

| Forest and Grassland | Coniferous forest |

| Deciduous forest | |

| Mixed forest | |

| Natural grassland | |

| Artificial grassland | |

| Water Surface | Inland water |

| Administrative Districts | Daily Mean Temperature (°C) | Daily Maximum Temperature (°C) | Daily Minimum Temperature (°C) | Tropical Night Days | Heatwave Days | Annual Precipitation (mm) | Precipitation Intensity | Heavy Rain Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muaneup | 13.6 | 18.6 | 9.3 | 7.7 | 10.9 | 1312.3 | 15.2 | 1.7 |

| Samhyang | 13.9 | 18.6 | 9.9 | 9.3 | 7.8 | 1253.0 | 13.8 | 1.5 |

| Illo | 13.9 | 18.9 | 9.6 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 1251.7 | 14.4 | 1.6 |

| Mongtan | 13.6 | 18.7 | 9.2 | 6.4 | 10.5 | 1348.8 | 15.0 | 1.7 |

| Unnam | 14.3 | 18.6 | 10.6 | 14.2 | 10.2 | 1138.7 | 14.8 | 1.3 |

| Cheonggye | 13.8 | 18.5 | 9.9 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 1240.4 | 14.4 | 1.4 |

| Haeje | 14.1 | 18.5 | 10.4 | 12.3 | 8.7 | 1162.5 | 14.1 | 1.1 |

| Hyeongyeong | 13.9 | 18.6 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 1242.3 | 14.4 | 1.3 |

| Mangun | 14.1 | 18.6 | 10.3 | 12.2 | 9.2 | 1197.9 | 14.7 | 1.2 |

| Jido | 14.3 | 18.3 | 10.9 | 14.0 | 7.1 | 1191.4 | 14.7 | 1.2 |

| Aphae | 14.2 | 18.5 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 7.7 | 1129.1 | 14.6 | 1.2 |

| Jeungdo | 14.4 | 18.4 | 11.0 | 15.1 | 7.0 | 1169.8 | 14.5 | 1.2 |

| Imja | 14.6 | 18.4 | 11.4 | 16.7 | 7.7 | 1173.5 | 14.7 | 1.3 |

| Jaeun | 14.3 | 18.1 | 10.8 | 13.7 | 6.5 | 1195.7 | 15.1 | 2.0 |

| Bigeum | 14.4 | 18.3 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 7.3 | 1134.7 | 14.8 | 1.7 |

| Docho | 14.3 | 18.1 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 6.3 | 1121.8 | 14.7 | 1.6 |

| Heuksan | 13.8 | 16.6 | 11.5 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 1077.5 | 14.1 | 1.6 |

| Haui | 14.3 | 18.1 | 10.8 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 1117.7 | 14.8 | 1.5 |

| Shinui | 14.2 | 18.2 | 10.7 | 7.1 | 5.0 | 1143 | 14.5 | 1.5 |

| Jangsan | 14.3 | 18.3 | 10.8 | 8.3 | 5.9 | 1129.8 | 14.4 | 1.5 |

| Anjwa | 14.2 | 18.3 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 8.4 | 1141.6 | 14.7 | 1.7 |

| Palgeum | 14.3 | 18.3 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 7.9 | 1129.3 | 14.7 | 1.7 |

| Amtae | 14.2 | 18.1 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 1170.1 | 14.6 | 1.6 |

| Daily Mean Temperature | Daily Maximum Temperature | Daily Minimum Temperature | Tropical Night Days | Heatwave Days | Annual Precipitation | Precipitation Intensity | Heavy Rain Days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build-up Area | −0.178 | 0.494 * | −0.398 | 0.100. | 0.510 * | 0.426 * | 0.043 | 0.027 |

| Agricultural Area | −0.343 | 0.760 ** | −0.664 ** | 0.198 | 0.806 ** | 0.619 ** | −0.004 | −0.199 |

| Wetland | 0.675 ** | −0.419 * | 0.481 * | 0.402 | −0.461 * | −0.440 * | 0.099 | −0.184 |

| Bare Land | 0.516 * | −0.782 ** | 0.750 ** | −0.031 | −0.754 ** | −0.624 ** | 0.082 | 0.375 |

| Forest & Grassland | −0.348 | −0.289 | −0.002 | −0.600 ** | −0.284 | 0.137 | 0.89 | 0.566 ** |

| Water Surface | 0.017 | 0.410 | −0.160 | 0.151 | 0.371 | 0.294 | −0.71 | −0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-E.; Hong, S.-K. Land Use and Nature-Based Climate Adaptation in Coastal and Island Regions: A Case Study of Muan and Shinan, South Korea. Sustainability 2026, 18, 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010380

Kim J-E, Hong S-K. Land Use and Nature-Based Climate Adaptation in Coastal and Island Regions: A Case Study of Muan and Shinan, South Korea. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010380

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jae-Eun, and Sun-Kee Hong. 2026. "Land Use and Nature-Based Climate Adaptation in Coastal and Island Regions: A Case Study of Muan and Shinan, South Korea" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010380

APA StyleKim, J.-E., & Hong, S.-K. (2026). Land Use and Nature-Based Climate Adaptation in Coastal and Island Regions: A Case Study of Muan and Shinan, South Korea. Sustainability, 18(1), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010380