Prioritization of Emergency Strengthening Schemes for Existing Buildings After Floods Based on Prospect Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Objectives and Significance

2. Materials and Methods

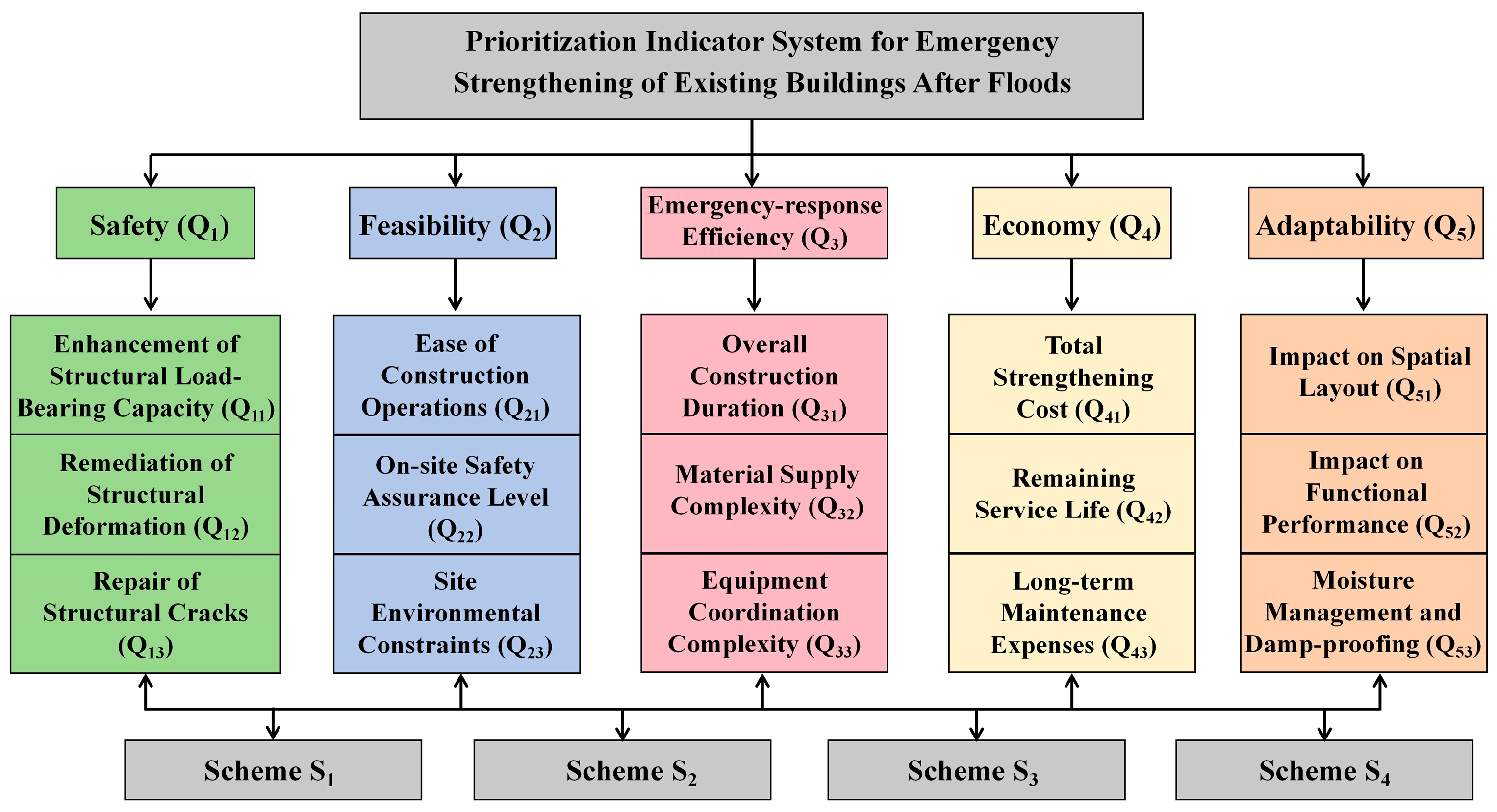

2.1. Establishment of the Indicator System

2.2. Model Formulation

2.2.1. Prospect Theory

2.2.2. Weighting Combination Methodology

- (1)

- Subjective Weighting

- (2)

- Objective Weighting

- (3)

- Combined Weighting

2.2.3. Model Construction Steps

- (1)

- Construction of the Initial Decision Matrix and Formulation of the Aspiration Vector

- (2)

- Normalization of Data

- (3)

- Calculate the Euclidean distance and the prospect value matrix.

- (4)

- Rank the alternatives

3. Results

3.1. Existing Building Overview

3.2. Computation Process

- (1)

- Data Collection for Indicators

- (2)

- Determination of the Aspiration Vector

- (3)

- Calculation of Euclidean Distance and Prospect Value Matrix

- (4)

- Establishment of the Weighting Scheme

- (5)

- Determination of Comprehensive Prospect Values and Ranking of Alternatives

3.3. Analysis of the Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility of the Proposed Model

4.2. Extended Applications of the Solution Optimization Model

4.3. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Xie, C.; Liu, G.; Fei, X. Study on evolvement law of urban flood disasters in China under urbanization. Hydro-Sci. Eng. 2018, 2, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development Issues Contingency Plan for Rural Housing in Flood Disasters and Guidelines for Rural Housing Assessment in Flood-Affected Areas. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/xinwen/gzdt/art/2021/art_304_761971.html (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Özuygur, A.R. Degrading seismic performance of tall shear wall buildings under earthquake sequences. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 52, 1718–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hong, Y.; Huang, D.; Dai, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z. Risk assessment management and emergency plan for uranium tailings pond. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2022, 15, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ullah, W.; Khan, A.; Ullah, S.; Ali, A.; Jan, M.A.; Bhatti, A.S.; Jan, Q. Assessment of multi-components and sectoral vulnerability to urban floods in Peshawar—Pakistan. Nat. Hazards Res. 2024, 4, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.; Espling, M. The role of communities in building urban flood resilience in Matola, Mozambique. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 118, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Yang, L.; Yue, B.; Ge, X.; Zhu, L. Experimental study on the flow pressure of flood on rural building models with different ratios of holes. J. Shenyang Jianzhu Univ. 2010, 26, 1039–1045. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S.; Yang, L.; Yue, B.; Ge, X.L.; Zhu, L.X. Experimental study on the impact of flood on rural building model. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2010, 30, 235–240. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Yue, B.; Yang, L.; Ge, X.; Zhu, L. Model experimental study of impact of flood with different heights of water on rural buildings. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2012, 52, 696–700. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W. Study on the Flood Resistance Performance of Village and Town Housing Buildings Under Flood Loads; Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology: Xi’an, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. Flood Flow Load Experiment and Its Effect on the Numerical Simulation of Village Buildings; Dalian University of Technology: Dalian, China, 2021. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhong, G.; Zhou, Z.; Fang, Q.; Zheng, W.; Liang, J. Characterization and impact factors of the damage to village buildings by mountain torrent disasters in Wenchuan county. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2022, 42, 1–11+23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Song, B.; Dong, Z.; Li, H. Study on evaluation method of anti-disaster performance of riverside buildings in mountain region under action of earthquake and flood. J. Build. Struct. 2024, 45, 164–177. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, W.; Zhong, G.; Zhen, Y.; Han, Z.; Li, Y. Flood risk assessment of rural buildings in Shouxihe basin based on vulnerability curve. J. Tongji Univ. 2024, 52, 68–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, H.; Mao, C.; Zhang, H. The optimal method for scheme selection of reinforcement of reinforced concrete frame structures damaged by earthquakes. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2017, 37, 97–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, F. Research on optimum selection of emergency reinforcement scheme for concrete structures after fire. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 52, 821–828. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, W. Research on optimum selection of centralized reinforcement and renovation scheme for dangerous housing in rural areas under the background of rural revitalization. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2021, 43, 106–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Hao, W. Research on bridge reinforcement scheme optimization based on empowerment relational degree. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2016, 13, 1317–1322. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Xu, Y. Reinforcement Planning Decision of Old Bridge Based on TOPSIS-AHP Method. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 919–921, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Luo, Q.Q. Study of Reinforcement Scheme for Tunnel Heaving due to Excavation of Sunken Plaza over Subway Tunnels. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 919–921, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Huan, T.; Sun, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Optimization of reinforcement scheme for old reinforced concrete factory building. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2022, 31, 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, D.; Khan, Z.; Mehra, A. Enhanced indexing using cumulative prospect theory utility function with expectile risk. Omega 2026, 139, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, C.; Wu, H.-N.; Meng, F.-Y.; Chen, R.-P. Assessing subway station flood risks with a resilience Framework: Combining weighting methods and two-dimensional cloud model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 168, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, L.; Deveci, M.; Martínez, L. Multi-source data driven decision-support model for product ranking with consumer psychology behavior. Inf. Fusion 2025, 118, 103014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M.; Zakerinejad, M. Development of practical-mathematical policy models using Fuzzy-Likert scale: Sustainable recycling of mining tailings in the industry 4.0 era. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.R.; Niksokhan, M.H.; Mousavi Janbehsarayi, S.F.; Nikoo, M.R. Integrated nonurban-urban flood management using multi-objective optimization of LIDs and detention dams based on game theory approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 462, 142737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Su, A.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Tong, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, A. Multiscale semantic segmentation and damage assessment of village houses in post-flood scenarios using an enhanced DeepLabv3 with dual attention mechanism. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 68, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, D.; Guan, Y.; Song, X.; Liu, G.; Fan, Z. Dual-constrained healthcare emergency facility location model under flood scenarios: A case study in the Maozhou River basin, Shenzhen, China. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2025, 28, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, H.; Cai, R.; Gu, T.; Zhang, W. Urban landscape patterns and residents’ perceptions of safety under extreme city flood disasters. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumura, T.; Nakamura, H. Feasibility of horizontal evacuation after flooding onset and its relationship with geographical characteristics: Insights from past flood events in Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 124, 105506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Mei, C. Optimizing emergency supply storage locations in urban flood disasters from the perspectives of cost and safety. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, G.; Singh, V.P.; Wu, W.; Fan, K.; Shen, Z. Flood disaster risk and socioeconomy in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 44, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, H.; Wan, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. Adaptability-enhanced evacuation path optimization and safety assessment for subway station passengers in floods: From uncertain challenge to reliable escape. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 163, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yan, G.; You, D.; Muhsen, S.; Elattar, S.; Ali, H.E.; Escorcia-Gutierrez, J. Creation of an advanced intelligent system for enhancing seismic and flood resilience in the design of real-time monitored structural frameworks. Structures 2025, 80, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Sadhu, A. Towards the effect of climate change in structural loads of urban infrastructure: A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Yu, Z.; Hameed, A. Cause, Stability Analysis, and Monitoring of Cracks in the Gate Storehouse of a Flood Diversion Sluice. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notice of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development on Issuing the Partial Revision of the National Standard Code for Seismic Design of Buildings. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2016/art_17339_228378.html (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- Hernández, H.; Díaz, L.; Rodríguez-Grau, G. Examining building deconstruction: Introducing a holistic index to evaluate the ease of disassembly. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 218, 108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.X.; Wong, P.K.-Y.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Chan, C.-F.; Leung, P.-H.; Tao, X. Enhancing visual-LLM for construction site safety compliance via prompt engineering and Bi-stage retrieval-augmented generation. Autom. Constr. 2025, 179, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Intelligent optimization of building complex layouts under multi-constraint conditions: A multi-agent modeling approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 131, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Post-Disaster Recovery and Reconstruction of Unsafe Housing in Chengde were Completed Ahead of the Scheduled Milestone. Available online: http://he.people.com.cn/BIG5/n2/2025/1019/c192235-41384280.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Zhou, J. Multi-objective decision making study for flood construction risk analysis in civil engineering. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 313, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Sheng, C.; Quddusi, M.R.; Aslam, R.W.; Mehmood, H.; Usman, S.Y.; Abdullah-Al-Wadud, M.; Liaquat, M.A.; Zulqarnain, R.M. Assessing the Cost of Hospital Building Materials: Effects of Temperature-Precipitation-Flood Dynamics on Landuse and Landcover. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 99, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jia, B.; Wang, W.; Gao, J.; Solé-Ribalta, A.; Borge-Holthoefer, J. From flood-prone to flood-ready: The restoration-adaptation interplay in building resilient multimodal transport networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 266, 111737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Third Flood of 2020 on the Yangtze River Passed Through the Three Gorges Dam Uneventfully. Experts from the Changjiang Water Resources Commission (CWRC) Assessed That While the Flood Control Situation Was Severe, It Remained Manageable. Available online: https://www.jfdaily.com/staticsg/res/html/web/newsDetail.html?id=274342 (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- The Investigation Report on the July 20 Catastrophic Rainstorm Disaster in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, Was Released. Available online: https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/bndt/202201/t20220121_407106.shtml (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Li, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Shu, L.; Xu, W. Deep reinforcement learning for optimal rescue path planning in uncertain and complex urban pluvial flood scenarios. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 144, 110543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Towe, C.; He, X. Heterogeneous flood zone effects on coastal housing prices—Risk signal and mandatory costs. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2025, 131, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Engel, B.A. Evaluating supply and demand relationship of urban flood regulation service and identifying priority areas for green infrastructure implementation in urban functional zones. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 126, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, M.; Brake, N.; Hariri Asli, H. A survey of flood warning sensor network operational and maintenance practices across the United States. Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 23, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, H. Dynamic impact assessment of urban floods on the compound spatial network of buildings-roads-emergency service facilities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 172007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, M.K.; Kumar, P.; Laskar, J.I.; Dutta, S. A risk-informed approach for combined functionality analysis of buildings and road network under flooding: A case study at Silchar, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 130, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchi, L.; Lucéro Gomez, P.; Zendri, E. On the contribution of tidal floods on damp walls of Venice. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 110, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- With Policy and Technology Acting as Dual Drivers, Beijing is Exploring New Pathways for the Renovation of Dilapidated and Old Buildings. Available online: https://www.cet.com.cn/xwsd/10271196.shtml (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, X.; Li, G. Research on cross market regime switching multi-period asset allocation based on prospect theory. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2018, 26, 44–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Que, C.; Lan, Y. Hesitant fuzzy TOPSIS multi-attribute decision method based on prospect Theory. Control Decis. 2017, 32, 864–870. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H. Research on Optimization of High Speed Railway Line Scheme Based on Prospect Theory; Southwest Jiaotong University: Chengdu, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Gao, M.; Cheng, X.D. Research on operational efficiency evaluation of anti-tank missile weapon system based on combination weighting. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2018, 38, 241–251. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Jia, L.; Pei, X. Multidimensional measurement and comprehensive evaluation of regeneration value of old industrial structures from the perspective of stock renewal. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, W.; Cui, K. Decision-making of civil building regeneration scheme based on improved TOPSIS method. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2022, 55, 160–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, B.; Greco, A.; Remøy, H.; Gruis, V.; Hamida, M.B. Towards desirable futures for the circular adaptive reuse of buildings: A participatory approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 122, 106259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarotti, C.; Senaldi, I.E. Advancing earthquake disaster management with earth observation data: From Copernicus gaps and challenges to requirements for tailored national-scale applications. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 131, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Pan, X.; Guo, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, C.; Zheng, J. Resilience quantification of offshore wind farm cluster under the joint influence of typhoon and its secondary disasters. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lin, J.; Wu, T.; Yuan, Z.; Cao, W. Assessing flood and waterlogging vulnerability and community governance in urban villages in the context of climate change: A case study of 89 urban villages in Shanghai. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 126, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-D.; Yoo, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kim, B. Flood prediction in urban areas based on machine learning considering the statistical characteristics of rainfall. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2025, 26, 100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Gan, W.; Zhang, K.; Xu, Z.; Gou, X. A dynamically updated consensus model for large-scale group decision-making driven by the evolution of public sentiment in emergencies. Inf. Fusion 2026, 126, 103484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Feng, Z.; Cao, S.-J. Mitigating outdoor-originated airborne radionuclides exposure utilizing existing building as hazardous shelter: Collaborative optimization of airtightness and indoor purification by a fugacity-based mathematical model. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 204, 108122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, F.; Clifton, J.; Burton, M.; Elrick-Barr, C.; Harvey, E.; Hill, G.; Zimmerhackel, J. Harnessing model-based group decision support systems for more effective stakeholder engagement: Reflections from the field. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 267, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Linguistic Fuzzy Numbers | Triangular Fuzzy Numbers |

|---|---|

| Extremely Poor | (0.00, 0.00, 0.17) |

| Poor | (0.00, 0.17, 0.33) |

| Slightly Poor | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Fair | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) |

| Slightly Good | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) |

| Good | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) |

| Extremely Good | (0.83, 1.00, 1.00) |

| Indicators | Indicator Properties | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q11 | + | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.83, 1.00, 1.00) | (0.83, 1.00, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) |

| Q12 | + | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) | (0.83, 1.00, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) |

| Q13 | + | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) |

| Q21 | − | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Q22 | + | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) |

| Q23 | − | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Q31 (day(s)) | − | 40 | 30 | 35 | 25 | 20–50 |

| Q32 | − | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Q33 | − | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Q41 (thousand CNY) | − | 900 | 1100 | 1000 | 800 | 700–1200 |

| Q42 (year(s)) | + | 25 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 20–30 |

| Q43 (thousand CNY/year) | − | 20 | 28 | 20 | 25 | 10–40 |

| Q51 | − | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.50, 0.67, 0.83) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Q52 | − | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) | (0.33, 0.50, 0.67) | (0.17, 0.33, 0.50) |

| Q53 | + | (0.83, 1.00, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.83, 1.00, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) | (0.67, 0.83, 1.00) |

| Q | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| Q2 | 1/2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| Q3 | 1/5 | 1/3 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Q4 | 1/7 | 1/5 | 1/3 | 1 | 2 |

| Q5 | 1/8 | 1/7 | 1/5 | 1/2 | 1 |

| Alternatives | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Prospect Value | −0.349 | −0.041 | 0.018 | 0.009 |

| Ranking | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Dimension | Flood Disasters | Earthquake Disasters | Wind Disasters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety | Enhancement of structural load-Bearing capacity, Remediation of structural deformation and Repair of structural cracks | Overall improvement of seismic resistance level, Reinforcement of critical structural components and Seismic measures for non-structural components | Wind resistance capacity, Integrity of the building envelope system and Roof wind uplift resistance |

| Feasibility | Ease of construction operations, On-site Safety assurance level and Site environmental constraints | Construction risk control during aftershocks, Safe operations in unstable structures and Guarantee of escape passageways | Operational safety under high-wind conditions, Windproof effectiveness of temporary measures and Wind-resistant securing of equipment |

| Emergency-response Efficiency | Overall construction duration, Material supply complexity and Equipment coordination complexity | Aftershock response, Secondary disaster risk mitigation and Rapid supporting capability | Timeliness of wind speed warning response, Speed of temporary protection deployment and Restoration of post-disaster energy |

| Economy | Total strengthening cost, remaining service life and long-term maintenance expenses | Life-cycle cost of seismic retrofitting, Impact on insurance premiums and Benefit from reduction in future seismic losses | Direct cost of windproofing reinforcement, Long-term maintenance costs in high-frequency wind disaster zones and Wind disaster insurance-related costs |

| Adaptability | Impact on spatial layout, Impact on functional performance, moisture Management and Damp-proofing | Balance between structural ductility, Applicability of seismic isolation technology and Historic building preservation requirements | Building aerodynamic shape optimization, Watertight performance of windows and doors and Coordination of drainage systems with wind resistance design |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Li, Q.; Shao, Y.; Li, Q.; Jia, L.; Liu, Y. Prioritization of Emergency Strengthening Schemes for Existing Buildings After Floods Based on Prospect Theory. Sustainability 2026, 18, 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010363

Li W, Li Q, Shao Y, Li Q, Jia L, Liu Y. Prioritization of Emergency Strengthening Schemes for Existing Buildings After Floods Based on Prospect Theory. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010363

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenlong, Qiuyu Li, Yayu Shao, Qin Li, Lixin Jia, and Yijun Liu. 2026. "Prioritization of Emergency Strengthening Schemes for Existing Buildings After Floods Based on Prospect Theory" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010363

APA StyleLi, W., Li, Q., Shao, Y., Li, Q., Jia, L., & Liu, Y. (2026). Prioritization of Emergency Strengthening Schemes for Existing Buildings After Floods Based on Prospect Theory. Sustainability, 18(1), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010363