Advancing the Sustainability of Poplar-Based Agroforestry: Key Knowledge Gaps and Future Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

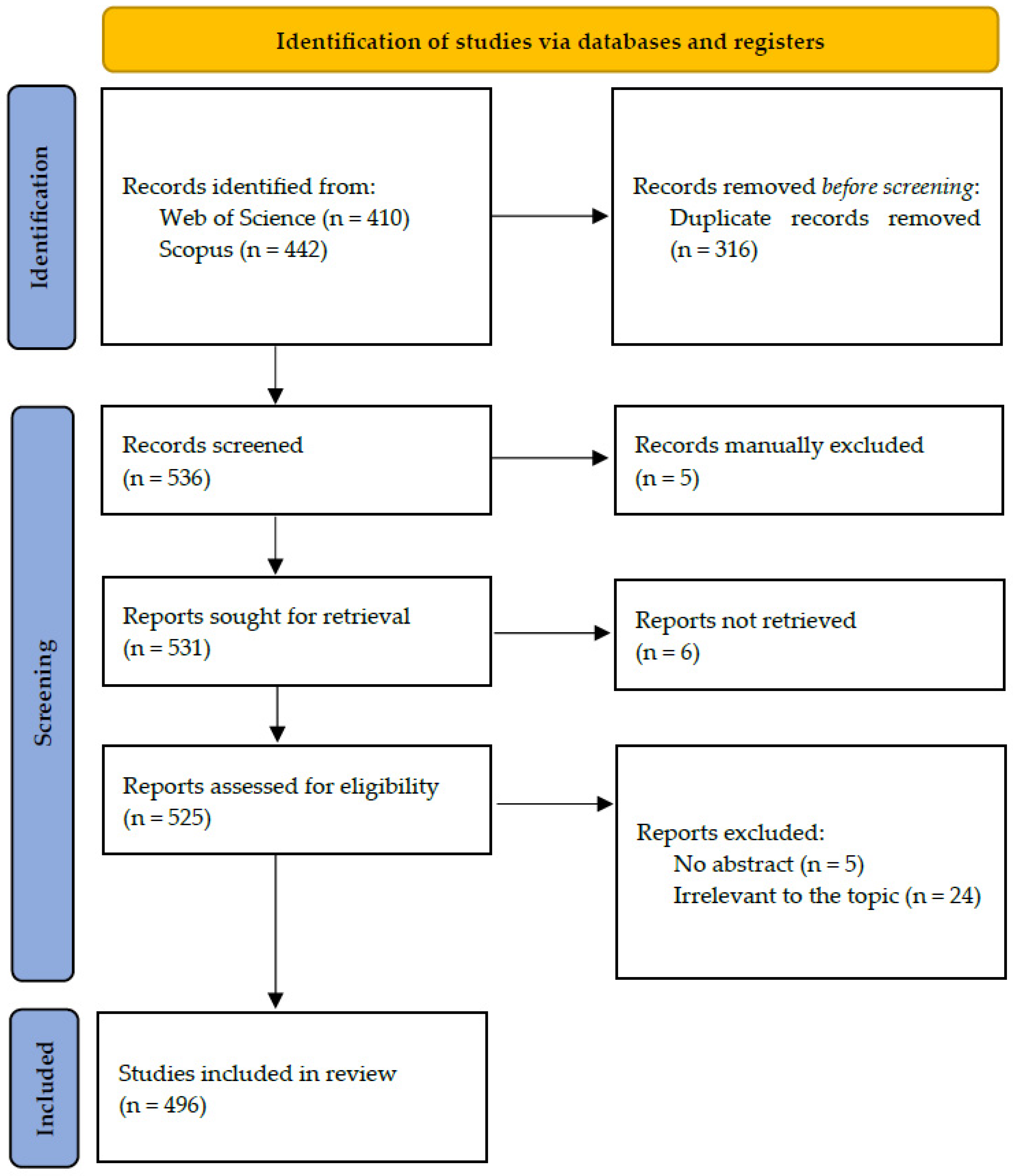

2. Materials and Methods

- Search strings and database queries

- Search parameters

- De-duplication and data quality control

- Automated duplicate detection based on DOI and exact title matching in Microsoft Excel.

- Manual screening of remaining records by title, first author, publication year, and journal to resolve missing or inconsistent DOI entries.

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Screening procedure

3. Results

3.1. A Bibliometric Review

3.2. A Classical Review

3.2.1. Global Research Trends on Poplars and Agroforestry

3.2.2. Populus Species Used in Agroforestry

3.2.3. Growth, Biomass, and Carbon Stocks of Poplars in Agroforestry: Implications for Sustainability

3.2.4. Ecological Characteristics and Sustainability of Poplar in Agroforestry Systems

3.2.5. Effects on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functions in Poplar-Based Agroforestry Systems

Hydrology and Nutrient Loss

Soil Nutrient Dynamics

Soil Fauna and Microorganisms

Aboveground Biodiversity

Phytoremediation Capacity

3.2.6. Agroforestry Systems with Poplars Used

Poplars and Cereals

Poplars and Vegetables

Poplars and Aromatic Herbs and Condiments

Poplars and Fruit Crops

Poplars and Multiannual Crops

Poplars and Oil Plants

Poplar and Fodder Crops

Poplar and Forage Crops and Livestock

4. Discussion

4.1. Bibliometric Review

4.2. Insights and Implications of Poplar-Based Agroforestry Research

4.3. Diversity, Distribution, and Functional Roles of Poplars in Agroforestry Systems

4.3.1. Geographic and Ecological Patterns

4.3.2. System Diversity and Functions

4.3.3. Role of Hybridization and Breeding

4.4. Poplar-Based Agroforestry Systems: Biomass, Carbon Sequestration, and Sustainability Considerations

4.5. Ecophysiological Implications of Poplar Integration in Agroforestry Systems

4.6. Ecological and Functional Implications of Poplar-Based Agroforestry Systems

4.7. Performance and Management of Sustainable Poplar-Based Agroforestry Systems

- Crop yield responses and shade tolerance

- Nutrient cycling, soil health, and climate benefits

- Economic viability

- Implications for system design

- -

- -

- -

4.8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Strategic genotype selection is foundational.

- (2)

- Integrating poplars with diversified cropping systems enhances multifunctionality.

- (3)

- Poplars play a critical role in landscape-level environmental regulation.

- (4)

- Urban and peri-urban applications are promising but require careful management.

- (5)

- Policymakers, breeders, and farmers should prioritize system design that integrates ecological and socio-economic objectives.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Chen, T.; Gao, K.; Xue, Y.; Wu, R.; Guo, B.; Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, R.; Jia, K.; et al. Unravelling the novel sex determination genotype with ‘ZY’and a distinctive 2.15–2.95 Mb inversion among poplar species through haplotype-resolved genome assembly and comparative genomics analysis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2024, 24, e14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Plants (Complete Lists). 2025. Available online: https://www.worldplants.de/world-plants-complete-list/complete-plant-list/?name=Populus-%25C3%2597-canadensis (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanical Garden of Kew. 2025. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/results?q=Populus (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mi, J.X.; Huang, J.L.; Shi, Y.J.; Tian, F.F.; Li, J.; Meng, F.Y.; He, F.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, F.; et al. A study on the distribution, origin, and taxonomy of Populus pseudoglauca and Populus wuana. J. Syst. Evol. 2025, 63, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, E.; Fransen, S.C.; Collins, H.P.; Stanton, B.J.; Himes, A.; Smith, J.; Guy, S.O.; Johnston, W.J. Effect of intercropping hybrid poplar and switchgrass on biomass yield, forage quality, and land use efficiency for bioenergy production. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 111, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilipović, A.; Headlee, W.L.; Zalesny, R.S., Jr.; Pekeč, S.; Bauer, E.O. Water use efficiency of poplars grown for biomass production in the Midwestern United States. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 14, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, W.; Peng, Y.; Wan, M.; Farooq, T.H.; Fan, W.; Lei, J.; Yuan, C.; Wang, W.; Qi, Y.; et al. Biomass production and carbon stocks in poplar-crop agroforestry chronosequence in subtropical central China. Plants 2023, 12, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, R.; Sharma, B.; Singh, H.; Dhakal, N.; Ayer, S.; Maraseni, T. Poplar plantation as an agroforestry approach: Economic benefits and its role in carbon sequestration in North India. J. Resour. Ecol. 2024, 15, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaviete, M.; Lazdina, D.; Bambe, B.; Bardule, A.; Bardulis, A.; Daugavietis, U. Productivity of different tree species in plantations and agricultural soils and related environmental impacts. Balt. For. 2015, 21, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Komán, S.; Németh, R.; Báder, M. An Overview of the Cuurent Situation of European Poplar Cultures with a Main Focus on Hungary. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhang, W.; Ding, C.; Yuan, Z.; Shen, L.; Zhang, B.; Chu, Y.; Su, X. Genomic Analysis Reveals the Fast-Growing Trait and Improvement Potential for Stress Resiatance in the Elite Poplar Variety Populus x euramericana ‘Bofeng 3’. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muftakhova, S.I.; Blonskaya, L.N.; Sabirzyyanov, I.G.; Konashova, S.I.; Timeryanov, A.S. Age dynamics of growth and development of Populus pyramidalis in city planting. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 78, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszkiewicz, J.; Długoński, A.; Fortuna-Antoszkiewicz, B.; Fialová, J. The Ecological Potential of Poplars (Populus L.) for City Tree Planting and Management: A Preliminary Study of Central Poland (Warsaw) and Silesia (Chorzów). Land 2024, 13, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornienko, V.; Reuckaya, V.; Shkirenko, A.; Meskhi, B.; Olshevskaya, A.; Odabashyan, M.; Shevchenko, V.; Teplyakova, S. Silvicultural and Ecological Characteristics of Populus bolleana Lauche as a Key Introduced Species in the Urban Dendroflora of Industrial Cities. Plants 2025, 14, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, M.; Hu, Y.; Thomas, B.R. Selection of Poplar Genotypes for Adapting to Climate Change. Forests 2019, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seserman, D.M.; Pohle, I.; Veste, M.; Freese, D. Simulating Climate Change Impacts on Hybrid-Poplar and Black Locust Short Rotation Coppices. Forests 2018, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, G.; Nawaz, M.F.; Zubair, M.; Azhar, M.F.; Gilasi, M.M.; Ashraf, M.N.; Qin, A.; Rahman, S.U. Role of Traditional Agroforestry Systems in Climate Change Mitigation through Carbon Sequestration: An Investigation from the Semi-Arid Region of Pakistan. Land 2023, 12, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, D.; Mateescu, E.; Tudor, R.; Ilie, L. Analysis of agroclimatic resources in Romania in the current and foreseeabla climate change—Concept and methodology of approaching. Sci. Papers. Ser. A. Agron. 2019, 62, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, M.; Clinciu, I.; Tudose, N.C.; Ungurean, C.; Mihalache, A.L.; Mărțoiu, N.E.; Tudose, O.N. Assessment of Seasonal Surface Runoff under Climate and Land Use Change Scenarios for a Small Forested Watershed: Upper Tarlung Watershed (Romania). Water 2022, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.; Tudose, N.C.; Ungurean, C.; Mihalache, A.L. Application of Life Cycle Assessment for Torrent Control Structures: A Review. Land 2024, 13, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.; Ilie, L.; Marin, D.L. Romanian soil resources—“Healty soils for a healthy life”. AgroLife Sci. J. 2015, 4, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Davidescu, S.O.; Clinciu, I.; Tudose, N.C.; Ungurean, C. An evaluating methodology for hydrotechnical torrent-control structures condition. Ann. For. Res. 2012, 55, 1844–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, A.L.; Marin, M.; Davidescu, Ș.O.; Ungurean, C.; Adorjani, A.; Tudose, N.C.; Davidescu, A.A.; Clinciu, I. Physical status of torrent control structures in Romania. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2020, 19, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudose, N.C.; Petritan, I.C.; Toiu, F.L.; Petritan, A.M.; Marin, M. Relation between Topography and Gap Characteristics in a Mixed Sessile Oak–Beech Old-Growth Forest. Forests 2023, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustățea, M.; Clius, M.; Tudose, N.C.; Cheval, S. An enhanced Machado Index of naturalness. Catena 2022, 212, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, D.; Petritan, A.M.; Tudose, N.C.; Toiu, F.L.; Scarlatescu, V.; Petritan, I.C. Structure and Spatial Distribution of Dead Wood in Two Temperate Old-Growth Mixed European Beech Forests. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2017, 45, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprică, R.; Tudose, N.C.; Davidescu, S.O.; Zup, M.; Marin, M.; Comanici, A.N.; Crit, M.N.; Pitar, D. Gender inequalities in Transylvania’s largest peri-urban forest usage. Ann. For. Res. 2022, 65, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusli, S.; Sumeni, S.; Sabodin, R.; Muqfi, I.H.; Nur, M.; Hairiah, K.; Useng, D.; van Noordwijk, M. Soil Organic Matter, Mitigation of and Adaptation to Climate Change in Cocoa-Based Agroforestry Systems. Land 2020, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudomo, A.; Leksono, B.; Tata, H.L.; Dwi Rahayu, A.A.; Umroni, A.; Rianawati, H.; Krisnawati, A.; Setyayudi, A.; Budi Utomo, M.M.; Pieter, L.A.G.; et al. Can Agroforestry Contribute to Food and Livelihood Security for Indonesia’s Smallholders in the Climate Change Era? Agriculture 2023, 13, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edris, S.; Gabourel-Landaverde, V.A.; Schnabel, S.; Rubio-Delgado, J.; Olave, R. Contribution of European Agroforestry Systems to Climate Change Mitigation: Current and Future Land Use Scenarios. Land 2025, 14, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/agroforestry-is-a-key-climate-solution--director-general-says-at-fao-council-side-event/en?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- IPCC. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/4/2022/11/SRCCL_Full_Report.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Gold, M.; Hemmelgarn, H.; Ormsby-Mori, G.; Todd, C. (Eds.) Training Manual for Applied Agroforestry Practices—2018 Edition; University of Missouri, Center for Agroforestry: Columbia, MO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, P.R.; Kumar, B.M.; Nair, V.D. Classification of agroforestry systems. In An Introduction to Agroforestry: Four Decades of Scientific Developments; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Enescu, C.M. Populus alba: A key species in the agroforestry system established in Cârcea, Dolj County. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2025, 57, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Lodhiyal, N.; Lodhiyal, L.S. Assessment of crop yield, productivity and carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems in Central Himalaya, India. Agroforest Syst. 2020, 94, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesny, R.J.; Rogers, E.R. Activities Related to the Cultivation and Utilization of Poplars, Willows, and Other Fast-Growing Trees in the United States, 2020—2023; US Rep. to IPC/UN FAO; Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Schroeder, W.; Saskatchewan, R.; Kort, J.; Saskatchewan, I.H. Activities Related to the Cultivation and Utilization of Poplars, Willows and Other Fast-Growing Trees in Canada. Period 2020–2023. In Proceedings of the Canadian Report to the 27th Session of the International Commission on Poplars and other Fast-Growing Trees Sustaining People and the Environment (IPC), Bordeaux, France, 21–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Achim, F.; Dincă, L.; Chira, D.; Răducu, R.; Chirca, A.; Murariu, G. Sustainable management of willow forest landscapes: A review of ecosystem functions and conservation strategies. Land 2025, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.; Coca, A.; Tudose, N.C.; Marin, M.; Murariu, G.; Munteanu, D. The role of trees in sand dune rehabilitation: Insights from global experiences. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratu, I.; Dincă, L.; Constandache, C.; Murariu, G. Resilience and decline: The impact of climatic variability on temperate oak forests. Climate 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, C.; Constandache, C.; Dincă, L.; Murariu, G.; Badea, N.O.; Tudose, N.C.; Marin, M. Pine afforestation on degraded lands: A global review of carbon sequestration potential. Front. For. Glob. Change 2025, 8, 1648094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, C.M.; Mihalache, M.; Ilie, L.; Dincă, L.; Constandache, C.; Murariu, G. Agricultural benefits of shelterbelts and windbreaks: A bibliometric analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobrawa, K. Poplars (Populus spp.): Ecological role, applications and scientific perspectives in the 21st century. Balt. For. 2014, 20, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Parmar, N.; Shandil, R.K.; Aggarwal, G.; Gaur, A.; Srivastava, D.K. Achievements and prospects of genetic engineering in poplar: A review. New For. 2021, 52, 889–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennenberg, H.; Wildhagen, H.; Ehlting, B. Nitrogen nutrition of poplar trees. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, R. Was there a socialist type of anthropocene during the cold war? Science, economy, and the history of the poplar species in hungary, 1945–1975. Hung. Hist. Rev. New Ser. Acta Hist. Acad. Sci. Hung. 2018, 7, 594–622. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, L.; Cantamessa, S.; Bergante, S.; Biselli, C.; Fricano, A.; Chiarabaglio, P.M.; Carra, A. Responses to drought stress in poplar: What do we know and what can we learn? Life 2023, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web of Science Core Collection. Available online: https://clarivate.com/academia-government/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-referencing/web-of-science/web-of-science-core-collection/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Elsevier. Scopus. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/scopus (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel?legRedir=true&CorrelationId=3bb60ab0-fe13-41a4-812b-2627667cf346 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Google. Geochart. Available online: https://developers.google.com/chart/interactive/docs/gallery/geochart (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- VOSviewer. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Rakesh Nanda, R.N.; Momi, G.S.; Sanjeev Chauhan, S.C. Awareness of adopters and non-adopters towards different aspects of poplar-based agroforestry in Punjab. Indian For. 2001, 127, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, S.B.; Dhillon, R.S.; Sirohi, C.; Keerthika, A.; Kumari, S.; Bharadwaj, K.K.; Yessoufou, K. Enhancing farm income through boundary plantation of poplar (Populus deltoides): An economic analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweier, J.; Becker, G. Economics of poplar short rotation coppice plantations on marginal land in Germany. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 59, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.E.; Simpson, J.A.; Thevathasan, N.V.; Gordon, A.M. Effects of tree competition on corn and soybean photosynthesis, growth, and yield in a temperate tree-based agroforestry intercropping system in southern Ontario, Canada. Ecol. Eng. 2007, 29, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, O.P.; Das, D.K. Energy dynamics in Populus deltoides G3 Marsh agroforestry systems in eastern India. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 29, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfapietra, C.; De Angelis, P.; Gielen, B.; Lukac, M.; Moscatelli, M.C.; Avino, G.; Cotrufo, M.F. Increased nitrogen-use efficiency of a short-rotation poplar plantation in elevated CO2 concentration. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollinger, J.; Lin, C.H.; Udawatta, R.P.; Pot, V.; Benoit, P.; Jose, S. Influence of agroforestry plant species on the infiltration of S-Metolachlor in buffer soils. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2019, 225, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, M.D.P.; Cornaglia, P.S.; Gundel, P.E.; Nordenstahl, M.; Jobbágy, E.G. Limits to recruitment of tall fescue plants in poplar silvopastoral systems of the Pampas, Argentina. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 80, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, K.; Goyal, S.; Kapoor, K.K. Microbial biomass dynamics during the decomposition of leaf litter of poplar and eucalyptus in a sandy loam. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1995, 19, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, L.M.; Soolanayakanahally, R.Y.; Guy, R.D.; Mansfield, S.D. Phosphorus storage and resorption in riparian tree species: Environmental applications of poplar and willow. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 149, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R.W.; Thomas, T.H.; Van Slycken, J. Poplar agroforestry: A re-evaluation of its economic potential on arable land in the United Kingdom. For. Ecol. Manag. 1993, 57, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Li, H.; Sun, Q.; Chen, L. Biomass production and carbon stocks in poplar–crop intercropping systems: A case study in northwestern Jiangsu, China. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 79, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergante, S. Poplar tree for innovative plantation models. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2022, 47, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bangarwa, K.S.; Sirohi, C. Potentials of poplar and eucalyptus in Indian agroforestry for revolutionary enhancement of farm productivity. In Agroforestry: Anecdotal to Modern Science; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Deswal, A.K.; Pawar, N.P.; Raman, R.S.; Yadav, J.N.; Yadav, V.P.S. Poplar (Populus deltoides)-based agroforestry system: A case study of Southern Haryana. Ann. Biol. 2014, 30, 699–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ivaniuk, I.; Fuchylo, Y.; Kyrylko, Y. Prospects for the use of Walnut and Poplar in agroforestry of Polissya and Forest-Steppe of Ukraine. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2023, 14, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, F.; Sotomayor, A.; Loewe, V.; Müller-Using, B.; Stolpe, N.; Zagal, E.; Doussoulin, M. Silvopastoral systems in temperate zones of Chile. In Silvopastoral Systems in Southern South America; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 183–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, G.S.; Van Rees, K.C. Soil organic carbon sequestration by shelterbelt agroforestry systems in Saskatchewan. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 97, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, B. Stem taper equations for poplars growing on farmland in Sweden. J. For. Res. 2013, 24, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaviete, M.; Makovskis, K.; Lazdins, A.; Lazdina, D. Suitability of fast-growing tree Species (Salix spp., Populus spp., Alnus spp.) for the establishment of economic agroforestry zones for biomass energy in the Baltic Sea region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, J.; Gagnon, D.; Truax, B.; Lambert, F. Understory plant diversity and biomass in hybrid poplar riparian buffer strips in pastures. New For. 2011, 42, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouttier, L.; Paquette, A.; Messier, C.; Rivest, D.; Olivier, A.; Cogliastro, A. Vertical root separation and light interception in a temperate tree-based intercropping system of Eastern Canada. Agrofor. Syst. 2014, 88, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.K.; Dhiman, R.C. Yield and quality of sugarcane under poplar (Populus deltoides)-based rainfed agroforestry. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2003, 73, 343–344. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjitkar, S.; Bu, D.; Sujakhu, N.M.; Gilbert, M.; Robinson, T.P.; Kindt, R.; Xu, J. Mapping tree species distribution in support of China’s integrated tree–livestock–crop system. Circ. Agric. Syst. 2021, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Song, J.; Cheng, B.; Wei, R.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Modeling the impact of climate change on the distribution of Populus adenopoda in China using the MaxEnt model. Forests 2025, 16, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tong, L.; Li, F.; Kang, S.; Qu, Y. Sap flow of irrigated Populus alba var. pyramidalis and its relationship with environmental factors and leaf area index in an arid region of Northwest China. J. For. Res. 2011, 16, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Wu, X.; Bahethan, B.; Yang, X.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X. Soil bacterial community characteristics and influencing factors in different types of farmland shelterbelts in the Alaer reclamation area. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1488089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovics, A.; Ábri, T.; Benke, A.; Illés, G.; Király, É.; Kovács, Z.; Schiberna, E.; Keserű, Z. Carbon credit revenue assessment for four shelterbelt projects following EU CRCF protocols. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, Y.; Makineci, E.; Özdemir, E. Biomass, carbon and nitrogen in single tree components of grey poplar (Populus × canescens) in an uncultivated habitat in Van, Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairova, M. Poplar species in Kazakhstan and some genotyping problems. Дoклaды HAH PK 2023, 345, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.H.; Miller, R.C.; Brooks, K.N. Impacts of short-rotation hybrid poplar plantations on regional water yield. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 143, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Meng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xin, J.; Hongzhuo, M.I.; Wang, Z. The Influence of the Planting Patterns of Forest Shelterbelts along the Yellow River in the Hobq Desert on Under-forest Vegetation Diversity. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2024, 6, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.D.; Lee, E.J. Potential tree species for use in the restoration of unsanitary landfills. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinsoo, K. 6.5.4 Estonia. In Environmental Applications of Poplars and Willows; Isebrands, J.G., Richardson, J., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Zitzmann, F. Seasonal use of different tree strip variants within a modern silvoarable agroforestry system by large and medium-sized mammals. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldén, A. Plant biodiversity in boreal wood-pastures: Impacts of grazing and abandonment. Jyväskylä Stud. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2016, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, C.D.; Bork, E.W.; Carlyle, C.N.; Chang, S.X. Agroforestry perennials reduce nitrous oxide emissions and their live and dead trees increase ecosystem carbon storage. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5956–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; An, Z.; Gross, C.; Chang, S.X. Forested lands have lower soil carbon priming effects than croplands in hedgerow agroforestry systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 394, 109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.W.; Bork, E.W. Aspen canopy removal and root trenching effects on understory vegetation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 230, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, C.; Boal, C.W.; DeStefano, S.; Hobbs, R.J. Nesting habitat and productivity of Swainson’s Hawks in southeastern Arizona. J. Raptor Res. 2013, 47, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, B.A.; Koski, R.D.; Jacobi, W.R. Roadside vegetation health condition and magnesium chloride (MgCl2) dust suppressant use in two Colorado, US counties. Arboric. Urban For. 2008, 34, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.S.; Li, Y.Z. Comparative experiments on the adaptability of some native poplars in Inner Mongolia. Sci. Silvae Sin. 1996, 32, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.; Peng, Y.; Zang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C. Adaptive responses of Populus kangdingensis to drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2005, 123, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanova, R.; Blonskaya, L.; Shamsutdinova, A. Cultivation of high-quality planting material of Populus trees for decarbonization of territories of the Forest-Steppe region of the European part of Russia. Pak. J. Bot. 2025, 57, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrov, V.; Miroshnyk, N.; Grabovska, T.; Shupova, T. Forest shelter belts in organic agricultural landscape: Structure of biodiversity and their ecological role. Folia For. Polonica. Ser. A. For. 2021, 63, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, T.; Takehashi, S.; Hoshino, T.; Noordeloos, M.E. Entoloma aprile (Agaricales, Entolomataceae) new to Japan, with notes on its mycorrhiza associated with Populus maximowiczii in cool-temperate deciduous forests of Hokkaido. Sydowia 2010, 62, 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kaganov, V.V. Epiphytic mosses in urban sites and the possibility of their use in biomonitoring (Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the IV National Scientific Conference with Foreign Participants: Geodynamical Processes and Natural Hazards (4th GeoProNH 2021), Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Russian Federation, 6–10 September 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 946, p. 012039. [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd-Roberts, K.; Gagnon, D.; Truax, B. Hybrid poplar plantations are suitable habitat for reintroduced forest herbs with conservation status. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yan, G.; Huang, B.; Sun, X.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Q. Long-term nitrogen addition alters nutrient foraging strategies of Populus davidiana and Betula platyphylla in a temperate natural secondary forest. Eur. J. For. Res. 2022, 141, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszkiewicz, J.; Fortuna-Antoszkiewicz, B.; Wiśniewski, P. The landscape significance of by-water shelterbelts—A case study of the Żerański canal in Warsaw. In Public Recreation and Landscape Protection; Mendel University in Brno: Brno, Czech Republic, 2020; pp. 494–498. [Google Scholar]

- Tsarev, A.P. The range of poplars available for the upland conditions of central forest-steppe. Lesn. Khozyaistvo 1980, 6, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, F.; Yan, X.; Zhang, C.; Jia, L. Characteristics of Stem Sap Flow of Two Poplar Species and their Responses to Environmental Factors in Lhasa River Valley of Tibet. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2019, 55, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, N.; Wang, B.; Zheng, K.; Zhao, Z.; Li, T. Contributions of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a reclaimed poplar forest (Populus yunnanensis) in an abandoned metal mine tailings pond, southwest China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Liang, G.; Lu, X.; Ding, S. Effects of corridor networks on plant species composition and diversity in an intensive agriculture landscape. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimeyeva, L.; Islamgulova, A.; Permitina, V.; Ussen, K.; Kerdyashkin, A.; Tsychuyeva, N.; Salmukhanbetova, Z.; Kurmantayeva, A.; Iskakov, R.; Imanalinova, A.; et al. Plant diversity and distribution patterns of Populus pruinosa Schrenk (Salicaceae) Floodplain Forests in Kazakhstan. Diversity 2023, 15, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimov, P.R. The concept of optimal landscape polarization as the basis of rational nature management. Ecol. Bull. Tashkent 2005, 4, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Ai, F.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, W.; Su, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Mao, K.; et al. Survival in the Tropics despite isolation, inbreeding and asexual reproduction: Insights from the genome of the world’s southernmost poplar (Populus ilicifolia). Plant J. 2020, 103, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breceda, A.; Arriaga, L.; Maya, Y. Forest resources of the tropical dry forest and riparian communities of Sierra de la Laguna Biosphere Reserve, Baja California Sur, Mexico. J. Ariz.-Nev. Acad. Sci. 1997, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chunya, Z.; Zhongqi, X.; Changming, M.; Shoujia, S.; Tengfei, Y. The factors influencing the poplar shelterbelt degradation in the Bashang Plateau of northwest Hebei Province. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Gao, J.; Zeng, D.; Zhou, X.; Sun, X. Three-dimensional (3D) structure model and its parameters for poplar shelterbelts. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2010, 53, 1513–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Song, Q.; Zhang, R.S.; Zhang, D.P.; Sun, J. Distribution characteristics of non-structural carbohydrate in main tree species of shelterbelt forests in horqin sandy land. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 56, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Khodakarimi, A. Hedgerow intercropping of Populus alba and alfalfa in West Azarbayjan Province, Iran. Iran. J. For. 2016, 8, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, N.; Vityi, A. Shelterbelts in Hungary. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Agroforestry Conference—Development of agroforestry in Europe (and beyond): Farmers’ perceptions, barriers and incentives, Montpellier, France, 23–25 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Headlee, W.L.; Zalesny, R.S., Jr.; Hall, R.B. Coarse root biomass and architecture of hybrid aspen ‘Crandon’ (Populus alba L. × P. grandidenta Michx.) grown in an agroforestry system in central Iowa, USA. J. Sustain. For. 2019, 38, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delate, K.; Holzmueller, E.; Frederick, D.D.; Mize, C.; Brummer, C. Tree establishment and growth using forage ground covers in an alley-cropped system in Midwestern USA. Agrofor. Syst. 2005, 65, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardule, A.; Lazdins, A.; Sarkanabols, T.; Lazdina, D. Fertilized short rotation plantations of hybrid aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx. × Populus tremula L.) for energy wood or mitigation of GHG emissions. Eng. Rural. Dev. 2016, 2016, 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, S.B.; Dhillon, R.S.; Ajit; Rizvi, R.H.; Sirohi, C.; Handa, A.K.; Kumari, S. Estimating biomass production and carbon sequestration of poplar-based agroforestry systems in India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 13493–13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Y.K.; Singh, B.K.; Kumar, H. Intercropping Under Poplar Based Agroforestry Systems. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369063643_Intercropping_under_Poplar_Based_Agroforestry_Systems (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Casaubon, E.A.; Cornaglia, P.S.; Peri, P.L. Installation of Silvopastoral Systems with Poplar in the Delta of the Paraná River, Argentina. In Agroforestry: Anecdotal to Modern Science; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 529–563. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Escobar, A.; Edwards, W.R.N.; Morton, R.H.; Kemp, P.D.; Mackay, A.D. Tree water use and rainfall partitioning in a mature poplar–pasture system. Tree Physiol. 2000, 20, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, P.D.; Mackay, A.D.; Matheson, L.A.; Timmins, M.E. The forage value of poplars and willows. Proc. New Zealand Grassl. Assoc. 2001, 63, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, D.; Cogliastro, A.; Olivier, A. Tree-based intercropping systems increase growth and nutrient status of hybrid poplar: A case study from two Northeastern American experiments. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henareh, J.; Ahmadloo, F.; Pato, M. Evaluation of yield and financial advantage of intercropping of poplar (Populus nigra 62/154) with alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) at Saatlou poplar research station of Urmia. For. Res. Dev. 2025, 10, 453–477. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, R.S.; Peringer, A.; Bugmann, H. Integrating models across temporal and spatial scales to simulate landscape patterns and dynamics in mountain pasture-woodlands. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachova, V.; Ferezliev, A. Improved characteristics of Populus sp. ecosystems by agroforestry practices. J. For. Soc. Croat./Sumar. List. Hrvat. Sumar. Drus. 2020, 144, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăilă, E.; Tudora, A.; Bîtcă, M.; Popovici, L. Alley cropping versus taungya system, two distinct types of agroforestry systems. Rev. De Silvic. şi Cinegetică 2021, 26, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, S.; Bhat, G.M.; Islam, M.A.; Rather, T.A.; Rashid, M.; Dar, M.U.D. Traditional agroforestry systems practiced in Leh district of Ladakh union territory—India. Pharma Innov. J. 2022, SP-11, 2946. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, C.; Jian-hui, X.U.E.; Dian-ming, W.U.; Mei-juan, J.I.N.; Yong-bo, W.U. Effects of poplar-amaranth intercropping system on the soil nitrogen loss under different nitrogen applying levels. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol./Yingyong Shengtai Xuebao 2014, 25, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Ran, A. Ecophysiological responses of three tree species to a high-altitude environment in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Forests 2018, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.X.; Jia, D.B.; Gao, R.Z.; Lu, J.P.; Lu, F.Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F. Water use characteristics of artificial sand-fixing vegetation on the southern edge of Hunshandake Sandy Land, Inner Mongolia, China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Ding, C.; Jiang, L.; Yu, H.; Han, R.; Xu, J.; Li, B.; Zheng, Z.; Li, C.; Qu, G.; et al. Evaluation of comprehensive effect of different agroforestry intercropping modes on poplar. Forests 2022, 13, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandil, R.I.K. Genetic transformation studies in Himalayan poplar (Populus ciliata Wall.). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Horticulture and Forestry, Bharsar, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Naithani, H.B.; Nautiyal, S. Indian poplars with special reference to indigenous species. For. Bull. 2012, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Linnebank, J.; Zitzmann, F. Mixing-in native thorny shrubs greatly improves the habitat quality of short rotation coppice strips within a modern agroforestry system for breeding birds. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 58, e03506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, J.D.; Johnson, G.; Sheaffer, C.C.; Current, D.A.; Wyse, D.L. Establishment and early productivity of perennial biomass alley cropping systems in Minnesota, USA. Agrofor. Syst. 2014, 88, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrnka, L.; Schmidt, C.S.; Švecová, E.B.; Vosátka, M.; Frantík, T. Impact of legume intercropping on soil nitrogen and biomass in hybrid poplars grown as short rotation coppice. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 182, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manevski, K.; Jakobsen, M.; Kongsted, A.G.; Georgiadis, P.; Labouriau, R.; Hermansen, J.E.; Jørgensen, U. Effect of poplar trees on nitrogen and water balance in outdoor pig production—A case study in Denmark. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuse, C.; Langhof, M. The impact of tree height and distance on crop yields in a temperate short rotation alley cropping agroforestry system: A multi-year study. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBell, D.S. Populus trichocarpa Torr. & Gray, black cottonwood. Silv. North Am. 1990, 2, 570–576. [Google Scholar]

- Majaura, M.; Sutterlütti, R.; Böhm, C.; Freese, D. High and dry: Barley (Hordeum vulgare) yield benefits from tree presence in a temperate alley cropping system during a drought year. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, P.J.; Incoll, L.D.; Hart, B.J.; Beaton, A.; Piper, R.W.; Seymour, I.L.; Reynolds, F.H.; Wright, C.; Pilbeam, D.J.; Grave, A.R. The Impact of Silvoarable Agroforestry with Poplar on Farm Profitability and Biological Diversity; Final Report to DEFRA Project code: AF0105; Cranfield University: Cranfield, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Yang, W.; Gao, X. Natural diet and food habitat use of the Tarim red deer, Cervus elaphus yarkandensis. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006, 51, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.M.; Arndt, S.K.; Bruelheide, H.; Foetzki, A.; Gries, D.; Huang, J.H.; Popp, M.; Gang, W.G.W.; Zhang, X.; Runge, M. Ecological basis for a sustainable management of the indigenous vegetation in a Central-Asian desert: Presentation and first results. J. Appl. Bot. 2000, 74, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Ceballos, G.C.; Vargas-Mendoza, M.; Ortiz-Ceballos, A.I.; Mendoza Briseño, M.; Ortiz-Hernández, G. Aboveground carbon storage in coffee agroecosystems: The case of the central region of the state of Veracruz in Mexico. Agronomy 2020, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qin, G. Effect of tree-crop intercropping on a young Populus tomentosa plantation. Front. For. China 2007, 2, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaske, K.J.; Garcia de Jalon, S.; Williams, A.G.; Graves, A.R. Assessing the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on economic profitability of arable, forestry, and silvoarable systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesmeier, A. Comparing the economic performance of poplar-based alley cropping systems with arable farming in Brandenburg under varying site conditions and policy scenarios. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Su, Y. Sap flow and tree conductance of shelter-belt in arid region of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2006, 138, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Su, P. Effects of tree shading on maize crop within a Poplar–maize compound system in Hexi Corridor oasis, northwestern China. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 80, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, H.P.; Kimura, E.; Polley, W.; Fay, P.A.; Fransen, S. Intercropping switchgrass with hybrid poplar increased carbon sequestration on a sand soil. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 138, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchioni, G.; Mantino, A.; Bosco, S.; Volpi, I.; Giannini, V.; Dragoni, F.; Tozzini, C.; Coli, A.; Mele, M.; Ragaglini, G. Mediterranean silvoarable systems for feed and fuel: The agroforces project. In Proceedings of the 4th European Agroforestry Conference, Agroforestry as Sustainable Land Use, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 28–30 May 2018; pp. 476–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sisi, D.E.; Karimi, A.; Pourtahmasi, K.; Taghiyari, H.R.; Asadi, F. The effects of agroforestry practices on vessel properties in Populus nigra var. betulifolia. IAWA J. 2010, 31, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medinski, T.V.; Freese, D.; Böhm, C. Soil CO2 flux in an alley-cropping system composed of black locust and poplar trees, Germany. Agrofor. Syst. 2015, 89, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fara, L.; Filat, M.; Chira, D.; Fara, S.; Nuţescu, C. Preliminary research on short cycle poplar clones for bioenergy production. In Proceedings of the International Conference RIO, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–17 July 2009; Volume 9, pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Andrašev, S.; Rončević, S.; Bobinac, M. Uticaj gustine sadnje na debljinsku strukturu klonova crnih topola S6-7 i M-1 (sekcija Aigerios (Duby)). Glas. Šumarskog Fak. Beogr 2003, 88, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Andrašev, S.; Rončević, S.; Vučković, M.; Bobinac, M.; Danilović, M.; Janjatović, G. Elementi strukture i proizvodnost zasada klona I-214 (Populus × Euramericana (Dode) Guinier) na aluvijumu reke Save. Glas. Šumarskog Fak. Beogr 2010, 101, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lukić, S.; Dožić, S. Efikasnost topole u vetrozaštiti na nekim lokalitetima u Vojvodini. Glas. Šumarskog Fak. Beogr 2006, 93, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Stajić, B. Izveštaj: Energetski Zasadi Brzorastućih Vrsta Drveća u Srbiji: Produkcija Biomase, Legislativa, Tržište i Uticaji na Životnu Sredinu—Potencijali i Ograničenja; UNDP Srbia: Belgrade, Srbia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biselli, C.; Vietto, L.; Rosso, L.; Cattivelli, L.; Nervo, G.; Fricano, A. Advanced breeding for biotic stress resistance in poplar. Plants 2022, 11, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, B.J.; Neale, D.B.; Li, S. Populus breeding: From the classical to the genomic approach. In Genetics and Genomics of Populus; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 309–348. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.W.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Luo, J.M.; He, C.Z.; Pu, Y.S.; An, X.M. Progress and strategies in cross breeding of poplars in China. For. Stud. China 2005, 7, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemenschneider, D.E.; Isebrands, J.G.; Berguson, W.E.; Dickmann, D.I.; Hall, R.B.; Mohn, C.A.; Stanosz, G.R.; Tuskan, G.A. Poplar breeding and testing strategies in the north-central US: Demonstration of potential yield and consideration of future research needs. For. Chron. 2001, 77, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Chaturvedi, O.P.; Jabeen, N.; Dhyani, S.K. Predictive models for dry weight estimation of above and below ground biomass components of Populus deltoides in India: Development and comparative diagnosis. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, G.; Chaturvedi, S.; Kaushal, R.; Nain, A.; Tewari, S.; Alam, N.M.; Chaturvedi, O.P. Growth, biomass, carbon stocks, and sequestration in an age series of Populus deltoides plantations in Tarai region of central Himalaya. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2014, 38, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.B.; Dhillon, R.S. Doubling farmers’ income through Populus deltoides-based agroforestry systems in northwestern India. Curr. Sci. 2019, 117, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, B.; Bastajić, D.; Dabić, S.; Novčić, Z.; Galić, Z.; Čortan, R.; Drekić, M.; Milović, M.; Poljaković-Pajnik, L. Osnivanje klonskih plantaža bele topole sadnicama bez korena. Topola 2021, 207, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, K.K. Biomass production and carbon balance in two hybrid poplar (Populus euramericana) plantations raised with and without agriculture in southern France. J. For. Res. 2018, 29, 1689–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, R.H.; Dhyani, S.K.; Yadav, R.S.; Singh, R. Biomass production and carbon stock of poplar agroforestry systems in Yamunanagar and Saharanpur districts of northwestern India. Curr. Sci. 2011, 100, 736–742. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar, P.P.; Chauhan, S.C.; Kaushal, R.K.; Das, D.K.; Ajit, A.; Arora, G.A.; Tewari, S.T. Carbon sequestration potential of poplar-based agroforestry using the CO2FIX model in the Indo-Gangetic Region of India. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 58, 439–447. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, B.; Sikka, R. Soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools in a chronosequence of poplar (Populus deltoides) plantations in alluvial soils of Punjab, India. Agrofor. Syst. 2015, 89, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Biswas, K.; Bisgrove, S.; Schroeder, W.R.; Thomas, B.R.; Mansfield, S.D.; Plant, A. Differences in drought resistance in nine North American hybrid poplars. Trees 2019, 33, 1111–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K.; Chaturvedi, O.P. Structure and function of Populus deltoides agroforestry systems in eastern India: 2. Nutrient dynamics. Agrofor. Syst. 2005, 65, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.I.; Li-hua, N.I.; Feng-hui, Y.U.A.N.; De-xin, G.U.A.N.; An-zhi, W.A.N.G.; Chang-jie, J.I.N.; Jia-bing, W.U. Canopy conductance characteristics of poplar in agroforestry system in west Liaoning Province of Northeast China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol./Yingyong Shengtai Xuebao 2012, 23, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Di, S.; De-xin, G.; Feng-hui, Y.; An-zhi, W.; Jia-bing, W. Time lag effect between poplar’s sap flow velocity and microclimate factors in agroforestry system in west Liaoning Province. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol./Yingyong Shengtai Xuebao 2010, 21, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.; Xue, J.; Jin, M.; Wu, Y.; Shi, H.; Xu, Y. Effects of poplar-wheat intercropping system on soil nitrogen loss in Taihu Basin. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2015, 31, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Filat, M.; Chira, D.; Nică, M.S.; Dogaru, M. First year development of poplar clones in biomass short rotation coppiced experimental cultures. Ann. For. Res. 2019, 62, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constandache, C.; Nistor, S. Preventing and control of soil erosion on agricultural lands by antierosional shelter-belts. Sci. Papers. Ser. E Land Reclam. Earth Obs. Surv. Environ. Eng. 2014, 3, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Galupa, D.; Talmaci, I.; Spitoc, I.; Vedutenco, D. Guidelines on the Creation and Rehabilitation of Protective Forest Shelterbelts. FAO, Ministry of Environment of Rep. Moldova, Moldsilva, ICAS, 2023. Available online: https://icas.com.md/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Indrumar-privind-crearea-si-reabilitarea-perdelelor-forestiere-de-protectie.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Kumar, A.; Ahlawat, K.S.; Sirohi, C.; Bhardwaj, K.K.; Kumari, S.; Singh, C.; Bedwal, S. Status of soil and plant micronutrients and their uptake by barley varieties intercropped with Populus deltoides plantation. Environ. Conserv. J. 2022, 23, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Zeng, D.H. Effect of land-use change from cropland to poplar-based agroforestry on soil properties in a semiarid region of Northeast China. Fresenius Env. Bull 2013, 22, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Kaur, H.; Kaur, S.; Kaur, N.; Gill, R.I.S. Nutrient return through litterfall from poplar plantation having different spacings in an agroforestry system. Agric. Res. J. 2024, 61, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Qian, Z.; Wang, B.; Yang, T.; Lin, Z.; Tian, D.; Tang, L. Effects of poplar agroforestry systems on soil nutrient and enzyme activity in the coastal region of eastern China. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 3108–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Chen, J.X.; Shan, L.M.; Qian, Y.C.; Chen, M.X.; Han, J.G.; Zhu, F.Y. Allelopathy research on the continuous cropping problem of poplar (Populus). Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 23, 1477–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şesan, T.E.; Oancea, F.; Toma, C.; Matei, G.M.; Matei, S.; Chira, F.; Alexandru, M. Approaches to the study of mycorrhizas in Romania. Symbiosis 2010, 52, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, G.W.; Gordon, A.M. Spatial and temporal distribution of earthworms in a temperate intercropping system in southern Ontario, Canada. Agrofor. Syst. 1998, 44, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beule, L.; Karlovsky, P. Tree rows in temperate agroforestry croplands alter the composition of soil bacterial communities. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhu, L.; Yang, T.; Qian, Z.; Xu, C.; Tian, D.; Tang, L. Poplar agroforestry systems in eastern China enhance the spatiotemporal stability of soil microbial community structure and metabolism. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, S.; Keten, A.; Stamps, W.T. Effect of alley cropping on crops and arthropod diversity in Duzce, Turkey. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2003, 189, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprodon, J.; Faus, J.; Salvanyà, P.; Soler-Zurita, J.; Romero, J.L. Suitability of poplar plantations for a cavity-nesting specialist, the Lesser Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos minor, in the Mediterranean mosaic landscape. Acta Ornithol. 2015, 50, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos, G.S.; Shannon, M.C.; Ajwa, H.; Draper, J.H.; Jordahl, J.; Licht, J. Phytoextraction and accumulation of boron and selenium by poplar (Populus) hybrid clones. Int. J. Phytoremediation 1999, 1, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrbac, M.; Manojlović, M.; Čabilinovski, R.; Petković, K.; Kovačević, D.; Pilipović, A. Drvenaste biljke u fitoremedijaciji zagađenja poljoprivrednog zemljišta nitratima i pesticidima. Topola 2022, 210, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Neto, A.; Panozzo, A.; Piotto, S.; Mezzalira, G.; Furlan, L.; Vamerali, T. Screening old and modern wheat varieties for shading tolerance within a specialized poplar plantation for agroforestry farming systems implementation. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 2765–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N.; Sah, V.K.; Satyawali, K.; Tewari, S.; Kandpal, G. Assessment of soil quality and wheat yield under open and poplar-based farming system in Tarai region of Uttarakhand. Indian J. Agric. Res. 2018, 52, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamdoust, J.; Sadati, S.E.; Sohrabi, H. Biomass production and carbon stocks of poplar-based agroforestry with canola and wheat crops: A case study. Balt. For. 2022, 28, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Xu, X.; Yu, X.; Li, Z. Poplar in wetland agroforestry: A case study of ecological benefits, site productivity, and economics. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 13, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, G.; Karasali, H.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Dynamics of changes in the concentrations of herbicides and nutrients in the soils of a combined wheat-poplar tree cultivation: A field experimental model during the growing season. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, O.P.; Pandey, I.B. Yield and economics of Populus deltoides G3 Marsh based inter-cropping system in eastern India. For. Trees Livelihoods 2001, 11, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.Q.; Li, P.; Guo, X.Q.; Sui, P.; Steinberger, Y.; Xie, G.H. Nitrogen and phosphorus uptake and yield of wheat and maize intercropped with poplar. Arid. Land Res. Manag. 2008, 22, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotto, S.; Panozzo, A.; Pasqualotto, G.; Carraro, V.; Barion, G.; Mezzalira, G.; Furlan, L.; Moore, S.S.; Vamerali, T. Phenology and radial growth of poplars in wide alley agroforestry systems and the effect on yield of annual intercrops in the first four years of tree age. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 361, 108814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, K.N.; Dhatt, A.S.; Gill, R.I.S. Growth and yield of onion (Allium cepa L.) varieties as influenced by planting time under poplar-based agroforestry system. Agric. Res. J. 2019, 56, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Kaur, N.; Dhat, A.S.; Gill, R.I. Optimization of onion planting time and variety under Populus deltoides-based agroforestry system in North-Western India. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Tewari, S.K.; Sah, V.K.; Singh, R.; Das, S.; Tewari, T. Growth, yield and economic evaluation of early mint technology under poplar-based silvi-medicinal system in the foothills of Himalaya. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantino, A.; Pecchioni, G.; Tozzini, C.; Mele, M.; Ragaglini, G. Agronomic performance of soybean and sorghum in a short rotation poplar coppice alley-cropping system under Mediterranean conditions. Agrofor. Syst. 2023, 97, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Kaur, N.; Gill, R.I.; Kaur, H.; Sardana, V. Indian mustard genotypes show varied response to sowing times under poplar (Populus deltoides Bartr.) in the irrigated agro-ecosystem of North-Western India. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, S.P.; Kaur, N.; Gill, R.I.S. Potato cultivars differ in response to date of planting in intercrop with poplar (Populus deltoides Bartr. ex Marsh.) in irrigated agro-ecosystem of north-west India. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 2345–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăilă, E.; Costăchescu, C.; Dănescu, F. Sisteme agrosilvice. Rev. De Silvic. și Cinegetică 2012, 30, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, G.P.S.; Gill, R.I.S.; Mangat, P.S. Growth performance of sunflower crop grown along the poplar boundary plantation. Indian J. Ecol. 2005, 32, 118–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tramacere, L.G.; Sbrana, M.; Antichi, D. N2 use in perennial swards intercropped with young poplars, clone I-214 (Populus × euramericana), in the Mediterranean area under rainfed conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadava, A.K. Cultivation of lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus ‘CKP-25’) under poplar-based agroforestry system. Indian For. 2001, 127, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, U.; Gupta, B.; Bhardwaj, D.R.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, D.; Chauhan, A.; Keprate, A.; Shilpa; Das, J. Tree spacings and nutrient sources effect on turmeric yield, quality, bio-economics and soil fertility in a poplar-based agroforestry system in Indian Himalayas. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 911–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.S.; Yang, T.; Shen, L.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, W.L.; Liu, T.T.; Lu, W.H.; Li, L.H.; Zhang, W. Root growth, distribution, and physiological characteristics of alfalfa in a poplar/alfalfa silvopastoral system compared to sole-cropping in northwest Xinjiang, China. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 1137–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Parmatma Singh, P.S. Performance of intercrops in agroforestry system: The case of poplar (Populus deltoides) in Uttar Pradesh (India). Indian For. 1999, 125, 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal, S.C.; Mishra, V.K.; Verma, K.S. Intercropping ginger and turmeric with poplar (Populus deltoides ‘G-3’ Marsh.). Agrofor. Syst. 1993, 22, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xu, X.; Shao, H.; Lu, H.; Yang, R.; Tang, B. Dynamics in soil quality and crop physiology under poplar–agriculture tillage models in coastal areas of Jiangsu, China. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 204, 104733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himshikha, H.; Charan Singh, C.S.; Charan Singh, C.S. Comparison of economics of poplar–fodder crop-based agroforestry under boundary and block plantation in Haridwar, North India. Indian J. Econ. Dev. 2018, 14, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Kemp, P.D.; Horne, D.J.; Jaya, I.K. Pasture production under densely planted young willow and poplar in a silvopastoral system. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 76, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro-Domínguez, N.; Nair, V.D.; Freese, D. Phosphorous dynamics in poplar silvopastoral systems fertilised with sewage sludge. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 223, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budău, R.; Timofte, C.S.C.; Mirisan, L.V.; Bei, M.; Dincă, L.; Murariu, G.; Racz, K.A. Living landmarks: A review of monumental trees and their role in ecosystems. Plants 2025, 14, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dincă, L.; Crișan, V.; Ienașoiu, G.; Murariu, G.; Drășovean, R. Environmental indicator plants in mountain forests: A review. Plants 2024, 13, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratu, I.; Dincă, L.; Schiteanu, I.; Mocanu, G.; Murariu, G.; Stanciu, M.; Zhiyanski, M. Sports in natural forests: A systematic review of environmental impact and compatibility for readability. Sports 2025, 13, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chețan, F.; Moraru, P.I.; Rusu, T.; Șimon, A.; Dincă, L.; Murariu, G. From contamination to mitigation: Addressing cadmium pollution in agricultural soils. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, G.; Dincă, L.; Munteanu, D. Trends and applications of principal component analysis in forestry research: A literature and bibliometric review. Forests 2025, 16, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.; Constandache, C.; Postolache, R.; Murariu, G.; Tupu, E. Timber harvesting in mountainous regions: A comprehensive review. Forests 2025, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timis-Gansac, V.; Dincă, L.; Tudose, N.C.; Constandache, C.; Murariu, G.; Cheregi, G.; Moțiu, P.T.; Derecichei, L.M. Community-based conservation in mountain forests: Patterns, challenges, and policy implications. Trees For. People 2025, 22, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepetiene, A.; Belova, O.; Fastovetska, K.; Dincă, L.; Murariu, G. Managing boreal birch forests for climate change mitigation. Land 2025, 14, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buciumeanu, E.C.; Guță, I.C.; Vizitiu, D.E.; Dincă, L.; Murariu, G. From vines to ecosystems: Understanding the ecological effects of grapevine leafroll disease. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.; Constandache, C.; Murariu, G.; Antofie, M.M.; Draghici, T.; Bratu, I. Environmental archaeology through tree rings: Dendrochronology as a tool for reconstructing ancient human–environment interactions. Heritage 2025, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudullo, G.; De Rigo, D. Populus alba in Europe: Distribution, habitat, usage and threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., de Rigo, D., Caudullo, G., Houston Durrant, T., Mauri, A., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 134–135. [Google Scholar]

- Apostol, E.N.; Stuparu, E.; Scarlatescu, V.; Budeanu, M. Testing Hungarian oak (Quercus frainetto Ten.) provenances in Romania. iForest 2020, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besliu, E.; Curtu, A.L.; Apostol, E.N.; Budeanu, M. Using adapted and productive European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) provenances as future solutions for sustainable forest management in Romania. Land 2024, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeanu, M.; Şofletea, N.; Petriţan, I.C. Among-population variation in quality traits in two Romanian provenance trials with Picea abies L. Balt. For. 2014, 20, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gora, E.M.; Bitzer, P.M.; Burchfield, J.C.; Schnitzer, S.A.; Yanoviak, S.P. Effects of lightning on trees: A predictive model based on in situ electrical resistivity. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 8523–8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormack, R.G.H. The effects of calcium ions and pH on the development of callus tissue on stem cuttings of balsam poplar. Can. J. Bot. 1965, 43, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, E.L. A pattern of parenchyma and canal resin chemistry in hardwoods and softwoods: 1. Review for softwoods. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2002, 17, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.; Pérez-Cruzado, C.; Cañellas, I.; Rodríguez-Soalleiro, R.; Sixto, H. Poplar short rotation coppice plantations under Mediterranean conditions: The case of Spain. Forests 2020, 11, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicol, G.; Yu, Z.; Berry, Z.C.; Emery, N.; Soper, F.M.; Yang, W.H. Tracing plant–environment interactions from organismal to planetary scales using stable isotopes: A mini review. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nautiyal, S.; Goswami, M.; Nidamanuri, R.R.; Hoffmann, E.M.; Buerkert, A. Structure and composition of field margin vegetation in the rural-urban interface of Bengaluru, India: A case study on an unexplored dimension of agroecosystems. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, J.D.; Liebig, M.A.; Merrill, S.D.; Tanaka, D.L.; Krupinsky, J.M.; Stott, D.E. Dynamic cropping systems: Increasing adaptability amid an uncertain future. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladysh, N.S.; Kovalev, M.A.; Lantsova, M.S.; Popchenko, M.I.; Bolsheva, N.L.; Starkova, A.M.; Bulavkina, E.; Karpov, D.; Kudryavtsev, A.; Kudryavtseva, A.V. The molecular and genetic mechanisms of sex determination in poplar. Mol. Biol. 2024, 58, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakewell-Stone, P. Populus nigra (black poplar). CABI Compend. CABI Compend 2023, 43535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manić, N.; Janković, B.; Dodevski, V. Model-free and model-based kinetic analysis of Poplar fluff (Populus alba) pyrolysis process under dynamic conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 143, 3419–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Luo, H.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zou, J.; Sheng, C.; Xi, Y. Multi-omics research on common allergens during the ripening of pollen and poplar flocs of Populus deltoides. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, H.P.; Fay, P.A.; Kimura, E.; Fransen, S.; Himes, A. Intercropping with switchgrass improves net greenhouse gas balance in hybrid poplar plantations on a sand soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2017, 81, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyden, B.; Carper, D.L.; Abraham, P.E.; Yuan, G.; Yao, T.; Baumgart, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; O’Malley, R.; Chen, J.G.; et al. Functional analysis of Salix purpurea genes support roles for ARR17 and GATA15 as master regulators of sex determination. Plant Direct 2023, 7, e546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurepa, J.; Smalle, J.A. Auxin/cytokinin antagonistic control of the shoot/root growth ratio and its relevance for adaptation to drought and nutrient deficiency stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Tahir, S.; Hassan, S.S.; Lu, M.; Wang, X.; Quyen, L.T.Q.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S. The Role of Phytohormones in Mediating Drought Stress Responses in Populus Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Crt. No. | Review | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agroforestry Systems | 94 | 2290 | 271 |

| 2 | Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment | 14 | 579 | 77 |

| 3 | Ecological Engineering | 11 | 744 | 73 |

| 4 | Forests | 17 | 207 | 64 |

| 5 | Forest Ecology and Management | 12 | 256 | 56 |

| 6 | Biomass & Bioenergy | 12 | 660 | 51 |

| 7 | Current Science | 10 | 127 | 45 |

| 8 | Sustainability | 7 | 70 | 43 |

| 9 | Plant and Soil | 9 | 361 | 37 |

| 10 | Journal of Environmental Management | 7 | 118 | 31 |

| 11 | Agronomy | 7 | 53 | 24 |

| 12 | Plos one | 3 | 64 | 14 |

| 13 | Geoderma | 5 | 312 | 8 |

| 14 | Science of the Total Environment | 3 | 53 | 8 |

| Cur. No. | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agroforestry | 173 | 517 |

| 2 | Poplar | 98 | 326 |

| 3 | Biomass | 76 | 297 |

| 4 | Plantations | 44 | 190 |

| 5 | Nitrogen | 42 | 183 |

| 6 | Dynamics | 41 | 182 |

| 7 | Carbon sequestration | 43 | 169 |

| 8 | Yield | 45 | 167 |

| 9 | Management | 34 | 158 |

| 10 | Sequestration | 35 | 155 |

| 11 | Agroforestry systems | 42 | 149 |

| 12 | Biomass production | 35 | 144 |

| 13 | Competition | 26 | 109 |

| 14 | Forest | 28 | 108 |

| 15 | Productivity | 32 | 108 |

| 16 | Carbon | 26 | 98 |

| Cur. No. | Area of Research | Region | Citing Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Assessment of crop yield, productivity, and carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems | India | Adhikari et al., 2020 [36] |

| 2 | Awareness of adopters and non-adopters towards different aspects of poplar-based agroforestry | India | Rakesh Nanda et al., 2001 [55] |

| 3 | Doubling farmers’ income through Populus deltoides-based agroforestry systems | India | Chavan et al., 2022 [56] |

| 4 | Economics of poplar short-rotation coppice plantations | Germany | Schweier and Becker, 2013 [57] |

| 5 | Effects of tree competition on corn and soybean photosynthesis, growth, and yield | Canada | Reynolds et al., 2007 [58] |

| 6 | Energy dynamics in Populus deltoides G3 Marsh agroforestry systems | India | Chaturvedi and Das, 2005 [59] |

| 7 | Increased nitrogen-use efficiency of a short-rotation poplar plantation in elevated CO2 concentration | Italy | Calfapietra et al., 2007 [60] |

| 8 | Influence of agroforestry plant species on the infiltration of S-Metolachlor in buffer soils | France | Dollinger et al., 2019 [61] |

| 9 | Limits to recruitment of tall fescue plants in poplar silvopastoral systems | Argentina | Clavijo et al., 2010 [62] |

| 10 | Microbial biomass dynamics during the decomposition of leaf litter of poplar | India | Chander et al., 1995 [63] |

| 11 | Phosphorus storage and resorption in poplars | Canada | Da Ros et al., 2018 [64] |

| 12 | Poplar agroforestry: a re-evaluation of its economic potential on arable land | United Kingdom | Willis et al., 1993 [65] |

| 13 | Poplar in wetland agroforestry | China | Fang et al., 2010 [66] |

| 14 | Poplar tree for innovative plantation models | Italy | Bergante, 2022 [67] |

| 15 | Potentials of poplar and eucalyptus in Indian agroforestry for revolutionary enhancement of farm productivity | India | Bangarwa and Sirohi, 2018 [68] |

| 16 | Poplar (Populus deltoides) based agroforestry system | India | Deswal et al., 2014 [69] |

| 17 | Prospects for the use of walnut and poplar in agroforestry | Ukraine | Ivaniuk et al., 2023 [70] |

| 18 | Silvopastoral systems in temperate zones | Chile | Dube et al., 2016 [71] |

| 19 | Soil organic carbon sequestration by shelterbelt agroforestry systems | Canada | Dhillon and Rees, 2017 [72] |

| 20 | Stem taper equations for poplars growing on farmland | Sweden | Hjelm, 2013 [73] |

| 21 | Suitability of fast-growing tree species (Salix spp., Populus spp., Alnus spp.) for the establishment of economic agroforestry zones for biomass energy | Latvia | Daugaviete et al., 2022 [74] |

| 22 | Understory plant diversity and biomass in hybrid poplar riparian | Canada | Fortier et al., 2011 [75] |

| 23 | Vertical root separation and light interception in a temperate tree-based intercropping system | Canada | Bouttier et al., 2014 [76] |

| 24 | Yield and quality of sugarcane under poplar (Populus deltoides)-based rainfed agroforestry | India | Chauhan and Dhiman, 2003 [77] |

| Cur.No. | Species, Hybrid, Variety, Clone–Name, Region | Agroforestry System | Use | Country-Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| section Populus | ||||

| 1 | P. adenopoda—Chinese aspen (E.Asia) | shelterbelts, windbreaks | R: fodder, timber, habitat loss, migration assistance. | CN—Ranjitkar et al., 2021 [78]; Tian et al., 2025 [79]. |

| 2a | P. alba var. pyramidalis | shelterbelts | R: greening arid zones; land reclamation. | CN—Xu et al., 2011 [80]; Tian et al., 2024 [81] |

| 3 | P. × canescens—gray poplar | shelterbelts, tree rows, gallery forests | R: habitat protection, sand control, carbon sequestration. | HU—Borovics et al., 2025 [82]; TR—Özcan et al., 2020 [83]; KZ—Kairova, 2023 [84]. |

| 4 | P. davidiana—Korean aspen (E.Asia) | shelterbelts, windbreak | R: fodder, timber, bioenergy feedstock; sand fixation. | CN—Ranjitkar et al., 2021 [78]. |

| 5 | P. grandidentata—bigtooth aspen (N.America) | farm woodlands | R: water control, SRC biomass energy, plant succession. | US—Perry et al., 2001 [85]. |

| 6 | P. sieboldii—Japanese aspen (E.Asia) | shelterbelts, extension forestry | R: sand control, wood, waste landfills reclamation | CN—Gao et al., 2024 [86]; KR—Kim & Lee, 2005 [87]. |

| 7 | P. tremula—common aspen (Europe, N.Asia) | shelterbelts, wood-pastures, alley cropping | R: wastewater purification; AC: oilseed rape, winter wheat; WP: grazing | EE—Heinsoo, 2014 [88]; DE—Zitzmann, 2025 [89]; FI—Oldén, 2016 [90]. |

| 8 | P. tremuloides—quaking aspen (E.N.America) | hedgerows, silvopastoral system | R: soil erosion, windbreaks, carbon sequestration, crop productivity | CA—Gross et al., 2022 [91]; CA—Chen et al., 2025 [92]; US—Powell & Bork, 2006 [93]. |

| section Aigeiros | ||||

| 10 | P. fremontii—Fremont cottonwood (W.-N.Am.) | shelterbelts, river corridors | R: biodiversity (bird nesting), soil humidity. | US—Nishida et al., 2013 [94]. |

| 11 | P. nigra L. var. pyramidalis | Shelterbelts | R: antidesertification; farmland protection | KZ—Kairova, 2023 [84]. |

| section Tacamahaca | ||||

| 12 | P. angustifolia—willow-leaved poplar (C.-N.Am.) | roadside, river corridors | R: riparian zones. | US—Goodrich et al., 2008 [95]. |

| 16 | P. hsinganica | forest farming | R: sand control, desert greening. | CN—Wen & Li, 1996 [96]. |

| 17 | P. intramongolica | riparian forest buffers | R: sand control, desert greening. | CN—Wen & Li, 1996 [96]. |

| 18 | P. kangdingensis | riparian forest buffers | R: drought resistance, land reclamation. | CN—Yin et al., 2005 [97]. |

| 19 | P. koreana—Korean poplar (NE Asia) | SRC forest blocks, urban forestry | R: pollution mitigation, carbon sequestration, urban greening | RU—Sultanova et al., 2025 [98]. |

| 20 | P. laurifolia—laurel-leaf poplar (central Asia) | shelterbelts, gallery forests, landscaping | R: biodiversity, phytoremediation of coal deposits and industrial dumps. | UA—Lavrov et al., 2021 [99]; KZ—Kairova, 2023 [84]. |

| 21 | P. maximowiczii—Japanese poplar (NE As.) | shelterbelts, roadside | R: farmland protection, urban green areas. | JP—Kasuya et al., 2010 [100]; RU- Kaganov, 2021 [101]. |

| 21a | P. maximowiczii × P. balsamifera | plantations | R: herb species with conservation status | CA—Boothroyd-Roberts et al., 2013 [102]. |

| 22 | P. simonii (NE Asia) P. simonii ‘Fastigiata’ | shelterbelts, by-water shelterbelts | R: sand fixation, wind protection, farmland shelter, decarbonization. | CN—Liu et al., 2022 [103]; Gao et al., 2024; [86] PL—Łukaszkiewicz et al., 2020 [104]. |

| 23 | P. suaveolens—Korean poplar (NE Asia) | shelterbelts | R: winter hardiness and drought resistance in forest-steppe. | RU—Tsarev, 1980 [105]. |

| 24 | P. szechuanica—Sichuan poplar (NE Asia) | shelterbelts | R: wood, wind and sand fixation, soil and water conservation. | CN—Xin et al., 2019 [106]. |

| 26 | P. yunnanensis—Yunnan poplar (E.Asia) | polluted land reclamation | R: desertification, phytoremediation, greening cities, roadside. | CN—Xiao et al., 2023 [107]. |

| section Leucoides | ||||

| 27 | P. lasiocarpa—Chinese necklace poplar (E.Asia) | hedgerow | R: corridor networks, landscape, diversity. | CN—Tang et al., 2014 [108]. |

| section Turanga | ||||

| 29 | P. pruinosa—gray-leaved poplar (Asia) | gallery forests, in arid territories | R: nutritional, regulating, and cultural ecosystem services, soil-strengthening. | KZ—Dimeyeva et al., 2023 [109]; UZ—Reimov, 2005 [110]. |

| 30 | P. ilicifolia—African poplar (E.Africa) | river galleries | R: IUCN vulnerable, wood, fodder | CN—Chen et al. 2020 [111]. |

| section Abaso | ||||

| 31 | P. brandegeei (Mexico) | river forest buffers | R: riparian forests. | MX—Breceda et al., 1997 [112]. |

| Intersectional hybrids | ||||

| e | P. × beijingensis (Asia) | shelterbelts | R: sand fixation, water conservation. | CN—Chunya et al., 2018 [113]; CN—Fan et al., 2010 [114]. |

| I | P. × xiaozhuanica (Asia) | shelterbelts | R: wind protection. | CN—Wang et al., 2021 [115]. |

| No. | Species, Hybrid, Variety, Clone–Name, Region | Agroforestry System | Use | Country-Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| section Populus | ||||

| 2 | P. alba—white poplar (S.Eu—C.Asia) | shelterbelts, taungya system | R: microclimate regulation, dune stabilization; TS: pepper, strawberry. | RO—Enescu 2025 [35]; IR—Khodakarimi 2016 [116]; HU—Frank & Vityi 2016 [117]. |

| 5a | P. alba × P. grandidenta ‘Crandon’ | agroforestry, alley cropping | AC: oat, red clover, red fescue, orchardgrass, hairy vetch. | US—Headlee et al., 2019 [118]; US—Delate et al., 2005 [119]. |

| 8a | P. tremula × P. tremuloides | intercropping | IC: reed canary grass, festulolium, galega | LV—Bardule et al., 2016 [120]. |

| section Aigeiros | ||||

| 9 | P. deltoides—eastern cottonwood (E.-N.Am.) | alley cropping, taungya system | IC/AC: div. cereals, vegetables, seeds, condiments, arom. herbs, fruits, sugarcane. | IN—Chavan et al., 2022 [121]; IN—Agarwal et al., 2023 [122]. |

| P. deltoides ‘Australiano 106/60’ P. deltoides ‘I78’ | silvopastoral system | SP: tall fescue, cocksfoot, ryegrass, timothy canarygrass, rescuegrass, swamp rice-grass, clover, alfalfa, oats, triticale; IC: browntop, soft brome, barley grass. | AR—Casaubon et al., 2018 [123]; CH—Dube et al., 2016 [71]; NZ—Guevara-Escobar et al., 2000 [124]; Kemp et al., 2001 [125]. | |

| 9a | P. deltoides × P. nigra DN3308; DN-177 | alley cropping | IC: soybean, barley, buckwheat, winter rye, winter wheat, maize, hay. | CA—Rivest et al., 2009 [126]; Bouttier et al., 2014. [76]. |

| 11 | P. nigra L.—black poplar (Europe) | IN- agrisilviculture s., silvopastoral | IC: div. cereals, vegetables, seeds, condiments, fruits | IR—Henareh et al., 2025 [127]; US- Snell et al., 2017 [128]. |

| 11a | P. × canadensis (P. deltoides × P. nigra)—hybrid black poplar P. × canadensis AF2 | shelterbelts, alley cropping, taungya system alley cropping | SB/IC/AC: div. cereals, vegetables, seeds, condiments, fruits, medicinal herbs, fodder, Christmas trees; AC(RSC): sorghum, soybean. | BG—Kachova & Ferezliev, 2020 [129]; RO—Mihaila et al., 2021 [130]. |

| section Tacamahaca | ||||

| 13 | P. balsamifera—Balsam poplar (N.-N.America) | agrosilviculture, silvopasture | FP/IC: div. cereals, vegetables, seeds, condiments, fruits | IN—Fatima et al., 2022 [131]; CA—Gross et al., 2022 [91]; KZ—Kairova, 2023 [84]. |

| 14 | Populus cathayana—(NE.Asia) | shelterbelts, block forests, intercropping | IC: amaranth; R: sand fixing. | CN—Jun et al., 2014 [132]; Gong et al., 2018 [133]; MN—Su et al., 2021 [134]. |

| 14a | P. cathayana × canadansis ‘xin lin 1’ | intercropping | IC: soybean, cilantro, cabbage, Chinese cabbage, corn, watermelon. | CN—Lu et al., 2022 [135]. |

| 15 | P. ciliata—Himalayan poplar (Asia) | intercropping, roadside, land slides | IC: fodder; R: wood, fodder, reclamation lands. | IN—Shandil, 2005 [136]; Naithani & Nautiyal, 2012 [137]. |

| 19a | P. koreana × P. trichocarpa ‘Koreana’ | alley cropping, silvoarable, hedgerows | AC: silage maize, spring barley, winter wheat, oilseed rap; | DE—Linnebank & Zitzmann, 2025 [138]. |

| 21b | P. maximowiczii × P. nigra ‘NM6’ | alley cropping | AC: native tallgrass-forb-legume polyculture, foder | US—Gamble et al., 2014 [139]. |

| 21c | P. maximowiczii × P. trichocarpa ‘NE-42’ | intercropping | IC: white clover, melilot | CZ—Mrnka et al., 2024 [140]; DK—Manevski et al., 2019 [141]. |

| ‘Hybride 275’ | alley cropping | AC: maize, barley, wheat, oilseed rap. | DE—Reuse & Langhof, 2025 [142]. | |

| ‘OP42’ | animal-plant system | SP: pig farm. | DK—Manevski et al., 2019 [141]. | |

| 25 | P. trichocarpa—W. balsam poplar (W.-N.Am.) | shelterbelts, alley cropping | R: shade, wind protection, field protection, AC: barley. | US—DeBell, 1990 [143]; DE—Majaura et al., 2025 [144]. |

| 25a | P. trichocarpa × P. trichocarpa Trichobel | silvoarable, alley cropping | AC: wheat, winter barley, cocksfoot, timothy, red fescue, white clover. | UK—Burgess et al., 2003 [145]. |

| 25b | P. trichocarpa × P. koreana ‘P-468’ | intercropping | IC: white clover, melilot. | CZ—Mrnka et al., 2024 [140]. |

| section Leucoides | ||||

| section Turanga | ||||

| 28 | P. euphratica—Euphrates poplar (N.Af, SW-C.Asia) | shelterbelts, inter-cropping, river gallery | R: farmland protection, sand control; IC: fodder/forage, Tarim red deer food. | CN—Tian et al., 2024 [81]; Qiao et al., 2006 [146]; Thomas et al., 2000 [147]. |

| section Abaso | ||||

| 32 | P. mexicana (Mexico) | shade crops | SC: coffee agroecosystems. | MX—Ortiz-Ceballos et al., 2020 [148]. |

| Intersectional hybrids | ||||

| a | P. × tomentosa—Chinese white poplar | windbreak, intercropping | IC: vegetables, peanut, wheat, soybean, watermelon; R: fodder, timber, fiber. | CN—Ranjitkar et al., 2021 [78]; Jiang & Qin, 2007 [149]. |

| b | P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides ‘TD3230’ | intercropping | IC: soybean, barley, buckwheat, winter rye, winter wheat. | CA—Rivest et al., 2009 [126]. |

| c | P. interamericana (P. deltoides × P. trichocarpa) | silvoarable, alley cropping | AC: wheat, barley, oilseed rape, red fescue, white clover, cocksfoot, timothy. | UK—Burgess et al., 2003 [145]; Kaske et al., 2021 [150]. |

| d | P. nigra × P. maximowiczii ‘NM3729’; ‘Max 1’ | intercropping, alley cropping | IC/AC: soybean, buckwheat, rye, oilseed rape, maize, barley, sorghum, lupine. | CA—Rivest et al., 2009 [126]; DE—Thiesmeier, 2024 [151]. |

| f | P. × gansuensis | shelterbelts | FP: maize; R: water protection, roadsides. | CN—Chang et al., 2006 [152]; Ding & Su, 2010 [153] |

| g | P. × generosa | intercropping | IC: switchgrass, R: bioenergy | US—Collins et al., 2020 [154]. |

| h | P. × generosa × P. nigra ‘Monviso’ | alley cropping | AC: sorghum, soybean, switchgrass, cocksfoot, alfalfa, French honeysuckle. | IT—Pecchioni et al., 2018 [155]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Enescu, C.M.; Mihalache, M.; Ilie, L.; Dinca, L.; Chira, D.; Vasić, A.; Murariu, G. Advancing the Sustainability of Poplar-Based Agroforestry: Key Knowledge Gaps and Future Pathways. Sustainability 2026, 18, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010341

Enescu CM, Mihalache M, Ilie L, Dinca L, Chira D, Vasić A, Murariu G. Advancing the Sustainability of Poplar-Based Agroforestry: Key Knowledge Gaps and Future Pathways. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010341

Chicago/Turabian StyleEnescu, Cristian Mihai, Mircea Mihalache, Leonard Ilie, Lucian Dinca, Danut Chira, Anđela Vasić, and Gabriel Murariu. 2026. "Advancing the Sustainability of Poplar-Based Agroforestry: Key Knowledge Gaps and Future Pathways" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010341