Drivers of Poverty Among Agricultural Households

These results are consistent with the evidence presented in the reviewed literature. Although the drivers were not grouped in the same way across previous studies, they consistently appear as variables influencing poverty levels, either positively or negatively, among agricultural or rural households in different contexts.

Household size plays a crucial role in increasing the risk of poverty, as larger families often encounter higher dependency ratios and greater consumption demands. This situation reduces per capita resources and limits the household’s capacity to invest in education, nutrition, and essential living conditions, leading to heightened monetary and multidimensional deprivation. The descriptive statistics reveal that the average household in the sample consists of around five members, suggesting that many agricultural families operate with relatively large units under constrained resources. In this study, the marginal effects indicate that each additional household member significantly raises the likelihood of experiencing multidimensional (4.2%), monetary (7.9%), and absolute poverty (6.4%). These moderate but persistent effects align with earlier research highlighting the economic burden associated with larger households [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. While some studies propose that larger families might gain from enhanced labour availability and income diversification opportunities [

60,

61], these benefits seem inadequate in the Togolese context for this sample size. The reliance on subsistence agriculture, limited technological access, and widespread structural barriers restrict the potential contributions of additional household members to productive endeavours, thereby maintaining high dependency burdens as a significant factor driving both monetary and multidimensional poverty among agricultural households.

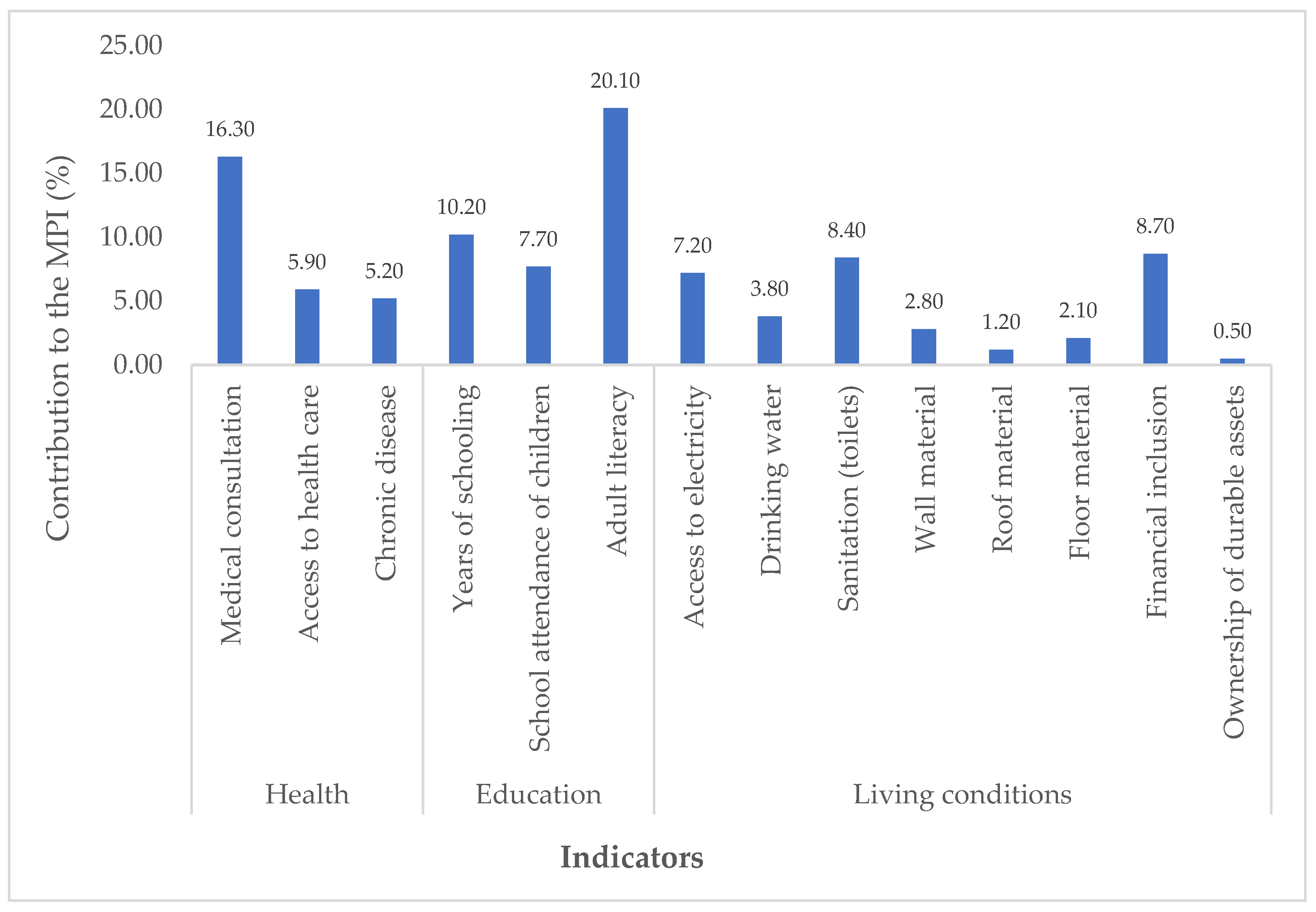

The educational level of the household head is linked to a reduced risk of experiencing monetary, multidimensional, and absolute poverty. This correlation likely stems from the fact that more educated household heads have better access to information, enhanced capacity to implement agricultural innovations, and increased opportunities for diversifying income sources. Previous research has highlighted these mechanisms as significant factors in poverty alleviation. For instance, [

62,

63,

64] highlight its role in expanding livelihood opportunities and improving households’ ability to escape poverty. However, education alone may not be enough; its impact depends on complementary factors such as access to credit, market participation, and extension services that help translate knowledge into productive outcomes. The descriptive statistics show that 44.8% of household heads have no formal education. This significant educational gap highlights the urgent need for investment in rural education and adult literacy programmes. By strengthening educational foundations, households could improve their ability to adopt better practices, engage in more lucrative activities, and ultimately escape the cycle of poverty, especially if these initiatives are complemented by broader institutional and market support.

The age of the household head appears to have a nuanced association with poverty. Descriptive statistics reveal that the average age of household heads is 47 years, indicating that many agricultural households are managed by individuals with considerable life and farming experience. This experience likely enhances their decision-making abilities, bolsters social networks, and improves agricultural risk management, which helps to explain the negative correlation between age and monetary poverty observed in the econometric analysis. This interpretation aligns with previous studies suggesting that age is often associated with better adaptive and managerial capacities [

65,

66]. However, the literature also indicates that the benefits of age may wane after a certain point, as increased age can lead to diminished physical productivity and heightened vulnerability to economic shocks [

67,

68]. This complexity may clarify why age does not show a significant relationship with multidimensional or absolute poverty in this study; while experience may foster income stability, it does not necessarily lead to enhancements in education, health, or overall living conditions for the household.

Overall, the socio-demographic findings indicate that household size and education are critical drivers influencing poverty, primarily through their effects on dependency ratios, human capital development, and labour productivity. These insights emphasize the necessity of focusing on Sustainable Development Goal 1 (No Poverty) and Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education). Addressing educational inequalities and reducing household vulnerabilities are vital steps toward enhancing the welfare of agricultural households in Togo.

The regression analysis indicates a consistent link between participation in off-farm activities and reductions in monetary, multidimensional, and absolute poverty, highlighting the crucial role of off-farm income in enhancing household welfare. This relationship can be attributed to several drivers. Off-farm employment offers a more stable income stream, which lessens reliance on rainfed agriculture and helps households manage consumption during times of climatic or market uncertainty. Additionally, it alleviates liquidity constraints, allowing families to invest in productive resources, education, health, and improved living conditions, thereby directly contributing to a decrease in multidimensional poverty. Furthermore, reallocating labour from low-yield subsistence farming to off-farm activities boost overall labour productivity and mitigates agricultural risks. However, despite these benefits, only 19.9 percent of households engage in off-farm activities, indicating that the majority of agricultural households are excluded from this important poverty-reducing pathway. Such limited participation may reflect structural barriers, including low educational attainment, limited labour mobility, and the scarcity of local employment opportunities. This finding is consistent with [

69,

70,

71], who argue that off-farm participation not only diversifies income streams but also reduces households’ exposure to climatic and market shocks.

Membership in agricultural cooperatives is associated with a 4.5% increase in multidimensional poverty (

p < 0.10) and shows no significant effect on monetary or absolute poverty. This counterintuitive result contrasts with most empirical studies, which generally find that cooperatives improve access to inputs, markets, and services [

72,

73,

74,

75]. Several mechanisms may explain this pattern. One possibility is adverse selection, whereby more vulnerable households join cooperatives seeking support, meaning that the association reflects pre-existing poverty rather than cooperative impact. Another explanation relates to internal governance challenges, including uneven participation or limited managerial capacity, which can reduce the effectiveness of service delivery for poorer members. Additionally, the financial and time costs of membership may disproportionately burden low-resource households, limiting their ability to benefit from cooperative activities. Similar findings in [

76] highlight that only well-functioning cooperatives with strong service capacity are able to reduce multidimensional poverty.

The results indicate that farm size remains an important protective factor against poverty. Larger landholdings enable households to expand production, diversify crops, and generate marketable surpluses, thereby improving income stability and reducing vulnerability. They also strengthen financial security by serving as collateral for credit, facilitating investments in productivity-enhancing inputs. Although landownership is common among households (63.3%), the average cultivated area of 3.89 hectares masks considerable variation in both size and quality, which helps explain why the poverty-reducing effect, while present, remains modest. This finding is in line with previous studies showing that larger farms improve production capacity, market participation, and liquidity [

77,

78]. However, structural constraints such as unequal land distribution, variable soil fertility, and limited access to complementary inputs like labour, irrigation, and technology, may restrict the extent to which additional land translates into substantial welfare gains.

Investment in livestock (TLU) exhibits varying impacts on different poverty metrics. Specifically, an increase of one Tropical Livestock Unit correlates with a 0.6% rise in multidimensional poverty, while simultaneously contributing to a 1% decrease in monetary poverty and a 0.5% reduction in absolute poverty. This discrepancy indicates that livestock primarily serves as a financial buffer, enabling households to manage consumption during economic shocks or temporary income declines. Although this short-term financial relief alleviates income-based poverty, it does not necessarily lead to enhancements in health, education, or living standards. Often, the proceeds from livestock sales are directed towards immediate needs rather than long-term investments in human capital, which may clarify why multidimensional poverty remains unchanged or even increases despite improvements in monetary welfare. This aligns with evidence from [

10,

79], who show that livestock strengthens rural resilience, stabilizes income, and reduces poverty severity by providing a flexible asset that households can mobilize during shocks. At the same time, findings from [

80] emphasize that these benefits are highly uneven, as many rural households own too few animals to reach viability thresholds, meaning that livestock ownership does not automatically improve multidimensional well-being and can even coincide with persistent deprivation.

Crop diversification is marginally significant in the absolute poverty model, where it decreases the likelihood of poverty by 4.1%. This indicates that while diversification may not influence poverty outcomes when assessed through a single dimension, its beneficial role becomes apparent when poverty is defined more rigorously, requiring households to be poor across multiple dimensions simultaneously. This pattern aligns with literature showing that diversification improves resilience through food security, dietary diversity, and risk reduction rather than through immediate income gains [

21,

81,

82,

83,

84]. Because these benefits tend to accumulate gradually rather than translate into short-term income or welfare improvements, their impact becomes visible only under a stricter poverty definition that captures simultaneous deprivations. This helps explain why its effect emerges in the absolute poverty measure but remains muted in the monetary and multidimensional indices taken separately.

Agricultural income serves as a crucial mechanism for alleviating poverty, as increased earnings from farming enhance household liquidity, enabling families to better meet their daily consumption needs and reducing their dependence on low-yield coping strategies like asset liquidation or informal loans. This rise in agricultural revenue not only helps stabilize food security but also facilitates the purchase of necessary inputs and allows for smoother consumption during periods of economic fluctuation, thereby decreasing the risk of both monetary and absolute poverty. Nevertheless, the benefits of agricultural income often remain confined to financial aspects, as improvements in earnings do not inherently lead to enhanced access to education, healthcare, housing quality, or essential services, areas that necessitate structural investments beyond individual households’ capabilities. This limitation highlights why agricultural income has a restricted impact on multidimensional poverty, which encompasses more profound and enduring forms of deprivation. These observations align with research indicating that while agricultural income can effectively diminish monetary poverty, lasting enhancements in overall welfare necessitate complementary public investments in rural infrastructure, health services, and educational systems [

85,

86].

Overall, the results show that key household decisions strongly shape welfare outcomes among agricultural households in Togo. Off-farm participation remains the most consistent poverty-reducing strategy, while larger farm sizes and livestock ownership provide important buffers that stabilize income and reduce vulnerability. Crop diversification also contributes to resilience, though its effects appear only under the stricter absolute poverty measure. In contrast, cooperative membership is associated with higher multidimensional poverty, pointing to organizational or targeting challenges that limit its expected benefits. These patterns are consistent with individualistic and cultural theories of poverty, which emphasize the role of household choices, asset management, and adaptive behaviour in determining welfare outcomes [

41,

42,

43]. They also reinforce the relevance of Sustainable Development Goals 1 (No Poverty) and 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), underscoring the need to strengthen household capabilities, improve access to productive assets, and expand viable livelihood pathways for rural populations.

Market access emerges as an important institutional driver for multidimensional deprivation. Although only about 13% of households report facing market constraints, this minority group shows a significantly higher likelihood of simultaneous deprivations in health, education, and living standards. While these constraints do not influence monetary or absolute poverty, their effect on multidimensional outcomes highlights the essential role of market integration in enabling households to access both economic opportunities and welfare-enhancing services. The underlying mechanism is straightforward: when market access is limited, households struggle to sell agricultural produce at fair or timely prices, reducing income stability and restricting their ability to finance essential expenditures such as schooling, healthcare, and housing improvements. Limited market access also constrains the purchase of key agricultural inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and tools, lowering productivity and keeping farmers trapped in low-return subsistence production. This result corroborates [

87], who contend that weak market integration perpetuates subsistence-oriented production and constrains the diffusion of welfare improvements. Improving rural infrastructure, particularly roads and communication networks, and reducing transaction costs are therefore critical to connecting smallholder agriculture with broader socioeconomic development.

The effect of shocks on poverty appears to be complex and context-dependent. In the present analysis, exposure to economic and natural shocks shows negative marginal associations with monetary and absolute poverty, while having no significant influence on multidimensional deprivation. This counterintuitive pattern suggests that households reporting shocks are not necessarily the most deprived. This pattern indicates that those who report shocks often possess enough assets or coping capacity to buffer their short-term welfare, whereas the poorest, who lack resources, savings, or consumption margins, may experience shocks without recognizing or reporting them. Notably, only about 9 percent of households report experiencing an economic shock, compared with nearly 39 percent reporting a natural shock, reflecting substantial variation in exposure and in households’ ability to perceive or declare such events. Relatively better-off households may be more capable of withstanding short-term disturbances through financial buffers, social networks, diversified income sources, or stronger market participation, allowing them to maintain consumption in the aftermath of shocks. Evidence from the literature supports this interpretation. The CGE model analysis by [

88] demonstrated that food price increases caused welfare deterioration primarily among low-income workers and self-employed agricultural employees. The research demonstrates that cash transfer programmes, together with food subsidies, specifically the former type, function as policy-based resilience mechanisms to reduce adverse welfare impacts from price increases. The research by [

89] demonstrates that rural Ethiopian households who experience recurring shocks experience worsening structural and stochastic poverty, but their ability to maintain poverty avoidance depends on their access to irrigation, level of literacy, vegetation cover, and non-farm income. The research supports the concept that resilience acts as a mediator between shocks and welfare because it enables households with better resources to withstand shocks without becoming poor. The research supports previous studies [

90,

91,

92], which demonstrate that multiple sequential shocks lead to the depletion of coping mechanisms, resulting in worsening poverty levels. The study reveals that shock-exposed households experience brief advantages which depend on their capacity to maintain adaptive and policy support systems. Given these dynamics, the observed associations should be interpreted cautiously. Several methodological factors may contribute to the unexpected direction of the estimates: (1) reverse causality (richer households have more assets at risk); (2) recall bias (poorer households may underestimate shocks); and (3) short-term measurement (cross-sectional data cannot capture long-term poverty impacts). A longitudinal analysis would be needed to disentangle these paths.

Taken together, these results provide strong empirical support for the structural theory of poverty and Sen’s entitlement approach. They highlight that poverty reduction cannot rely solely on household-level initiatives; instead, it requires systemic reforms in markets, financial systems, and public service provision [

93]. Sustainable poverty alleviation thus depends on transforming the institutional environment in which rural households operate, ensuring that opportunities and entitlements are equitably distributed. This aligns with Sustainable Development Goals 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), which emphasize the need for inclusive institutions, fair resource distribution, and structural change to support long-term development.