Grain Transhipment Drives Extremely High Winter Waterbird Concentrations in the Port of Gdynia, Southern Baltic

Abstract

1. Introduction

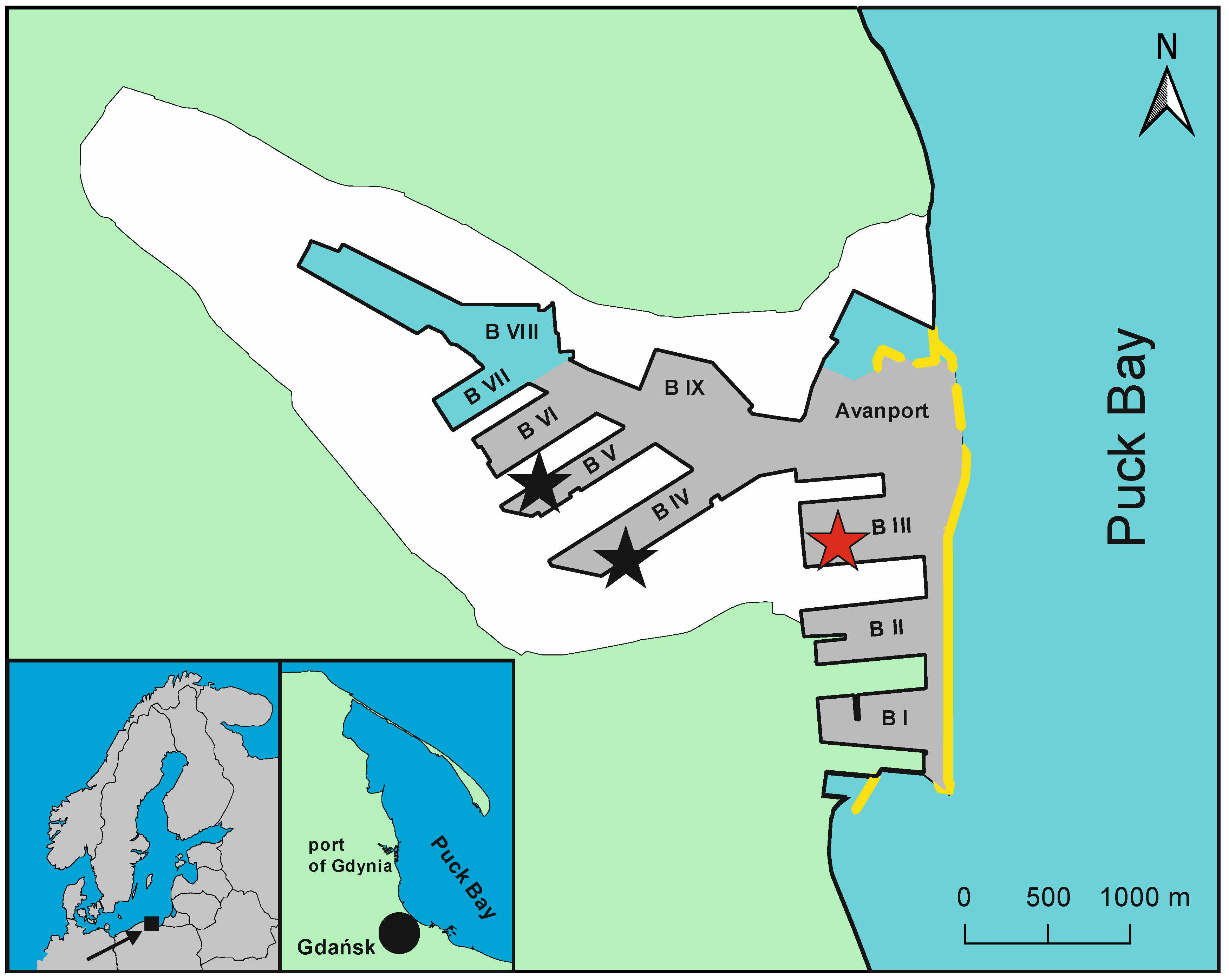

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

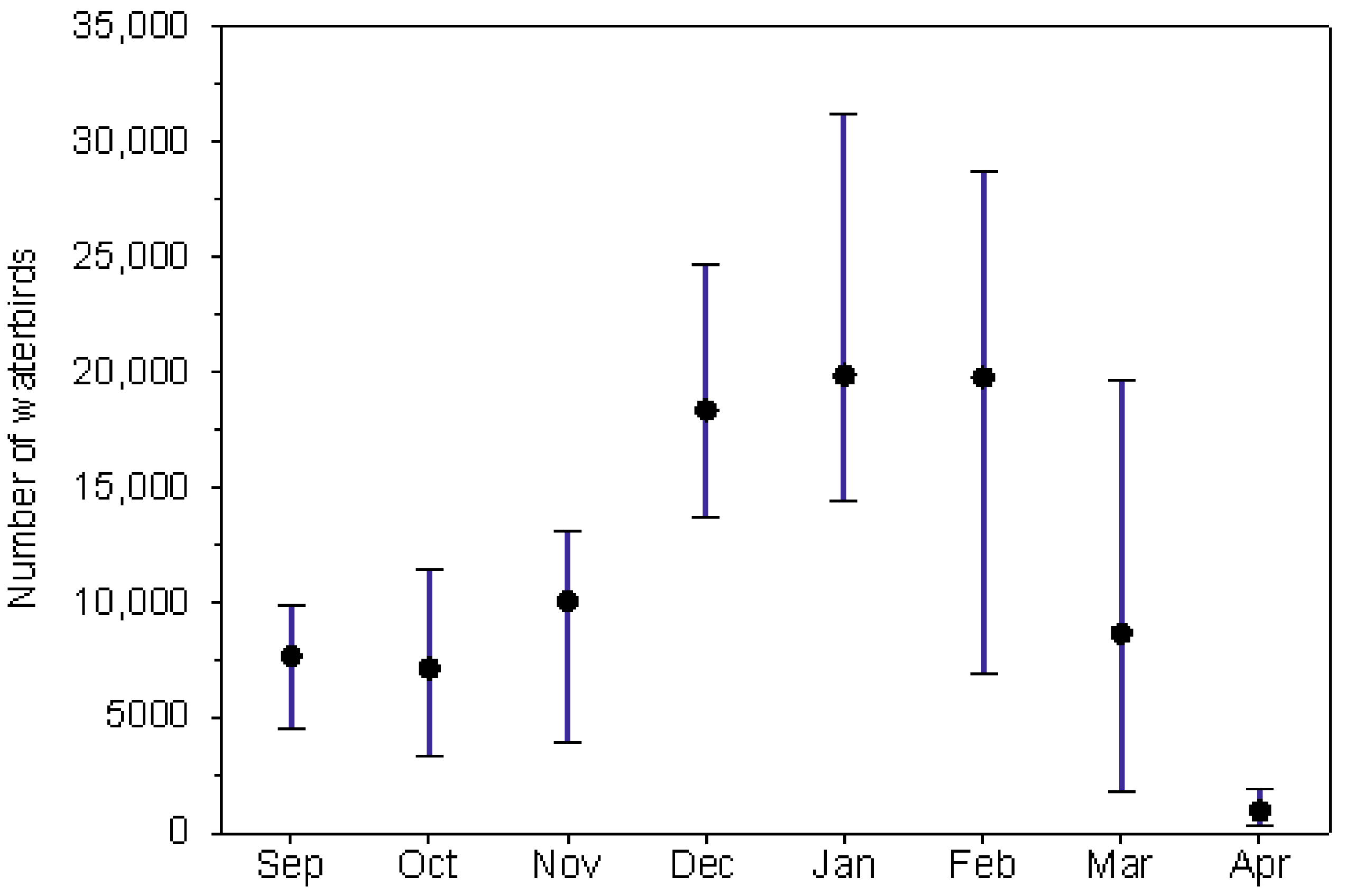

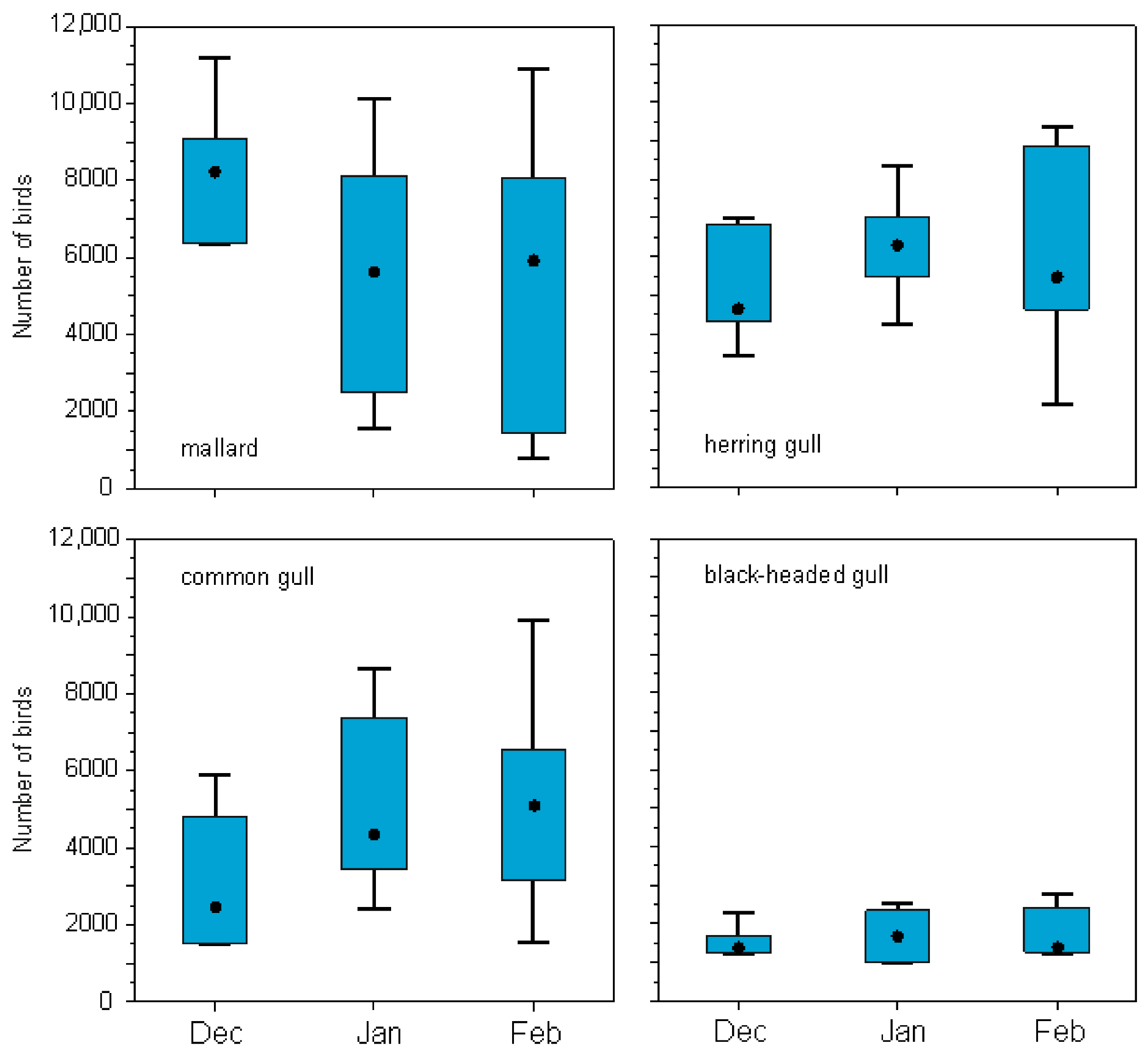

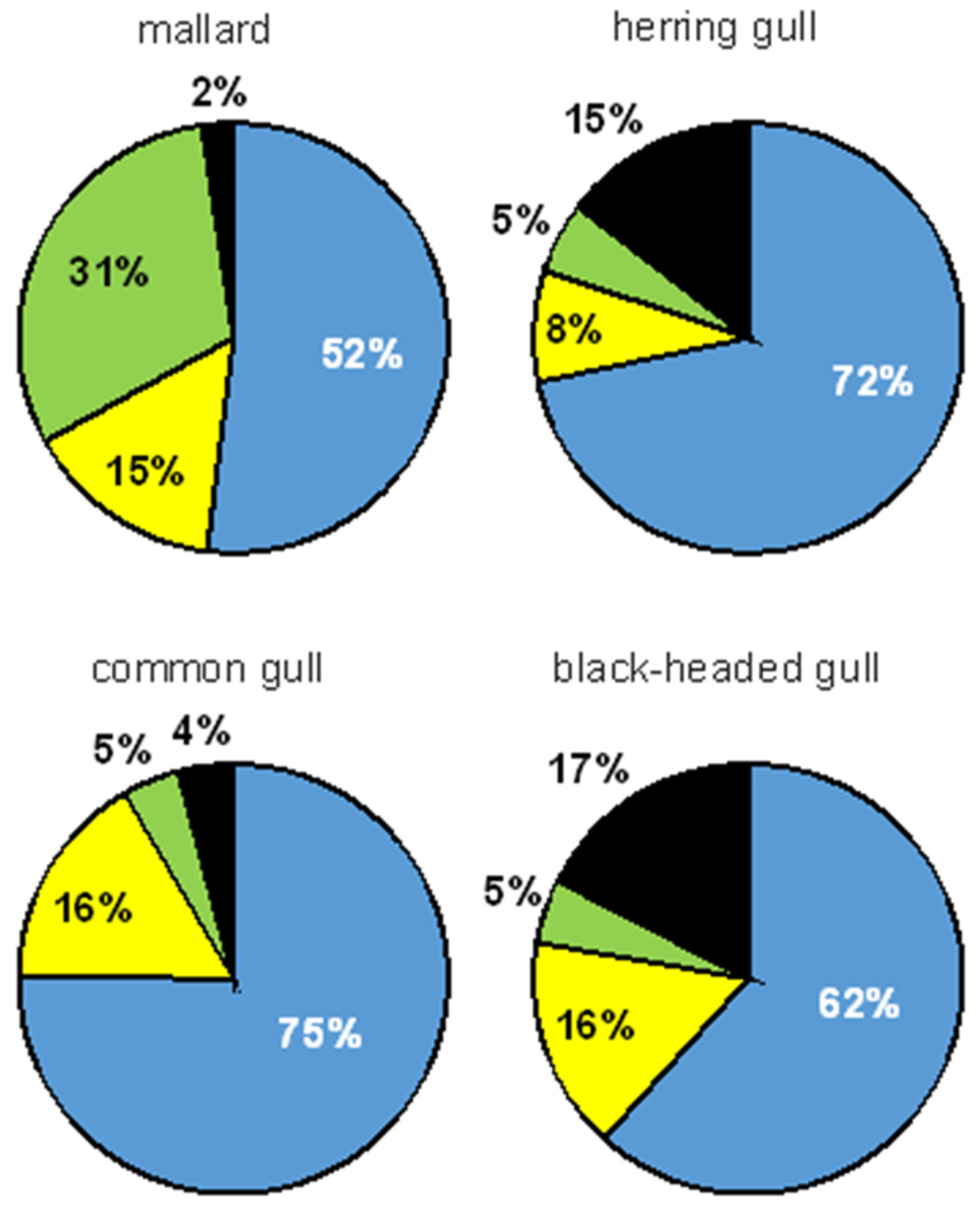

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Species | Mean Number | Mean Number in Winter Months | Maximum Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrea cinerea | + | 1 | |

| Cygnus olor | 4 | 2 | 14 |

| Anser serrirostris | + | 1 | |

| Anser albifrons | + | + | 2 |

| Mareca strepera | + | 2 | |

| Mareca penelope | + | 8 | |

| Anas platyrhynchos | 3229 | 6232 | 8200 |

| Anas acuta | 2 | + | 3 |

| Aythya ferina | 1 | 3 | 47 |

| Aythya fuligula | 272 | 677 | 1662 |

| Aythya marila | 2 | 4 | 80 |

| Clangula hyemalis | 11 | 20 | 110 |

| Bucephala clangula | + | + | 1 |

| Mergellus albellus | 1 | 2 | 15 |

| Mergus serrator | + | 7 | |

| Mergus merganser | 1 | 2 | 24 |

| Gavia arctica | + | + | |

| Tachybaptus ruficollis | + | + | + |

| Podiceps cristatus | 5 | 12 | 26 |

| Podiceps auritus | + | 3 | |

| Phalacrocorax carbo | 552 | 269 | 3300 |

| Fulica atra | 95 | 209 | 350 |

| Chroicocephalus ridibundus | 1288 | 1624 | 2611 |

| Larus canus | 2109 | 4482 | 10,751 |

| Larus marinus | 8 | 8 | 20 |

| Larus argentatus | 4005 | 5815 | 7500 |

| Alca torda | + | + | 1 |

References

- Marzluff, J.M. Worldwide urbanization and its effects on birds. In Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World; Marzluff, J.M., Bowman, R., Donnelly, R., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Norwell, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chace, J.F.; Walsh, J.J. Urban effects on native avifauna: A review. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2006, 74, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurucz, K.; Purger, J.J.; Batáry, P. Urbanization shapes bird communities and nest survival, but not their food quantity. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilova, K.V.; Eremkin, G.S. Waterfowl wintering in Moscow (1985–1999): Dependence on air temperatures and the prosperity of the human population. Acta Ornithol. 2001, 36, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.; Witkowska, M. The effect of the temperature on local differences in the sex ratio of Mallards Anas platyrhynchos wintering in an urban habitat. Acta Oecol. 2023, 119, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, M.; Wesołowski, W.; Markiewicz, M.; Pakizer, J.; Neumann, J.; Ożarowska, A.; Meissner, W. The intensity of supplementary feeding in an urban environment impacts overwintering Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) as wintering conditions get harsher. Avian Res. 2024, 15, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, S.J.; Galbraith, J.A.; Smith, J.A.; Jones, D.N. Garden bird feeding: Insights and prospects from a north-south comparison of this global urban phenomenon. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belant, J.L.; Seamans, T.W.; Gabrey, S.W.; Dolbeer, R.A. Abundance of gulls and other birds at landfills in Northern Ohio. Amer. Midl. Nat. 1995, 134, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arroyo, M.; Gómez-Martínez, M.A.; MacGregor-Fors, I. Litter buffet: On the use of trash bins by birds in six boreal urban settlements. Avian Res. 2023, 14, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.P.; Galloway, S.; Burt, G.; Mcdonald, J.; Hopkins, I. A port system simulation facility with an optimization capability. Int. J. Comput. Intell. 2003, 3, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderton, P.M. Port Management and Operations; Informa: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuur, J.; Koks, E.E.; Hall, J.W. Ports’ criticality in international trade and global supply-chains. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, P.; Snep, R.P.H.; Schotman, A.G.M.; Jochem, R.; Stienen, E.W.M.; Slim, P.A. Seabird metapopulations: Searching for alternative breeding habitats. Popul. Ecol. 2009, 51, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.; Bzoma, S.; Zięcik, P.; Wybraniec, M. Nesting of the Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis in Poland in 2006–2013. Ornis Pol. 2014, 55, 96–104, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.; Kośmicki, A.; Rydzkowski, P. Abundance and distribution of waterbird community in the Port of Gdynia during the non-breeding season. Ornis Pol. 2024, 65, 324–336, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struve, B.; Nehls, H.W. Ergebnisse der Internationalen Wasservogelzählung im Januar 1990 an der Deutschen Ostseeküste. Seevögel 1992, 13, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudard, C.; Quaintenne, G.; Ward, A.; Dronneau, C.; Dalloyau, S.; Dupuy, J. Synthèse des Dénombrements d’Anatidés, de Foulques et de Limicoles Hivernant en France à la Mi-Janvier 2017; LPO: Rochefort, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubas, D. Factors affecting different spatial distribution of wintering Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula and Goldeneye Bucephala clangula in the western part of the Gulf of Gdańsk (Poland). Ornis Svec. 2003, 13, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witalis, B.; Iglikowska, A.; Ronowicz, M.; Kukliński, P. Biodiversity of epifauna in the ports of Southern Baltic Sea revealed by study of recruitment and succession on artificial panels. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 249, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manel, S.; Mathon, L.; Mouillot, D.; Bruno, M.; Valentini, A.; Lecaillon, G.; Gudefin, A.; Deter, J.; Boissery, P.; Dalongeville, A. Benchmarking fish biodiversity of seaports with eDNA and nearby marine reserves. Conserv. Lett. 2024, 2024, e13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madon, B.; Haderle, R.; Arotcharen, E.; David, R.; Fontaine, Q.; Marengo, M.; Thomasz, H.; Torralba, A.; Valentini, A.; Jung, J.-L. eDNA and citizen science reveal hidden fish biodiversity in climate-stressed urban ports of the Mediterranean Sea. Environ. DNA 2025, 7, e70142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, N.; Saengsupavanich, C. Oceanic environmental impact in seaports. Oceans 2023, 4, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Cariou, P.; Sun, Z. The impact of port congestion on shipping emissions in Chinese ports. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 128, 104091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, C.; Mendoza, G.; Levin, L.A.; Zirino, A.; Delgadillo-Hinojosa, F.; Porrachia, M.; Deheyn, D.D. Macrobenthic community response to copper in Shelter Island Yacht Basin, San Diego Bay, California. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumiło, E.; Szubska, M.; Meissner, W.; Bełdowska, M.; Falkowska, L. Mercury in immature and adults Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) wintering on the Gulf of Gdańsk area. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2013, 42, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodziach, K.; Staniszewska, M.; Falkowska, L.; Nehring, I.; Ożarowska, A.; Zaniewicz, G.; Meissner, W. Gastrointestinal and respiratory exposure of water birds to endocrine disrupting phenolic compounds. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W. Significant reduction in the impact of oil spills and chronic oil pollution on seabirds: A long-term case study from the Gulf of Gdańsk, southern Baltic Sea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Walsh, G.; Lerner, D.; Fitza, M.A.; Li, Q. Green innovation, managerial concern and firm performance: An empirical study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chao, Y.; Xie, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Xue, C. Green innovation in ports: Drivers, domains, and challenges. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1664611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.S.H.; Woo, J.K.; Kim, T.G. Green Ports and Economic Opportunities. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Maritime Industry; Froholdt, L.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trozzi, C.; Vaccaro, R. Environmental impact of port activities. In Maritime Engineering and Ports II; Brebbia, C.A., Olivella, J., Eds.; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2000; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Żukowska, S. Concept of green seaports. Case study of the seaport in Gdynia. Pr. Kom. Geogr. Komun. PTG 2020, 23, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madon, B.; David, R.; Torralba, A.; Jung, A.; Marengo, M.; Thomas, H. A review of biodiversity research in ports: Let’s not overlook everyday nature! Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 242, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signal Maritime. Grain Seaborne Trade Impact on the Dry Bulk Freight Market. 2025. Available online: https://www.thesignalgroup.com/newsroom/grain-seaborne-trade-impact-on-the-dry-bulk-freight-market (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Wilson, W.W.; Koo, W.W.; Taylor, R.; Dahl, B. Long-term forecasting of world grain trade and U.S. Gulf exports. Transp. Res. Rec. 2005, 1909, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.; Stępniewska, K.; Bzoma, S.; Kośmicki, A. Numbers of waterbirds on the Bay of Gdańsk between May 2019 and April 2020. Ornis Pol. 2020, 60, 245–252, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Statistical Yearbook of Maritime Economy; Statistics Poland and Statistical Office in Szczecin: Warsaw, Poland; Szczecin, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Palmowski, T.; Wendt, J.A. The impact of new developments and modernisation at the Polish ports of Gdańsk and Gdynia on changes in port transshipments. Prz. Geogr. 2021, 93, 269–290, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowska, S.; Palmowski, T.; Połom, M. Spatial development of the seaport on the example of Gdynia. Pr. Kom. Geogr. Komun. PTG 2021, 24, 94–105, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synak-Miłosz, E.; Rozmarynowska-Mrozek, M. Polish Seaports in 2024. Summary and Future Outlook; Actia Forum: Gdynia, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Caixeta-Filho, J.V.; Péra, T.G. Post-harvest losses during the transportation of grains from farms to aggregation points. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2018, 7, 209–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durinck, J.; Skov, H.; Jensen, F.P.; Pihl, S. Important Marine Areas for Wintering Birds in the Baltic Sea; Ornis Consult: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Skov, H.; Heinänen, S.; Žydelis, R.; Bellebaum, J.; Bzoma, S.; Dagys, M.; Durinck, J.; Garthe, S.; Grishanov, G.; Hario, M.; et al. Waterbird Populations and Pressures in the Baltic Sea; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wardecki, Ł.; Chodkiewicz, T.; Beuch, S.; Smyk, B.; Sikora, A.; Neubauer, G.; Meissner, W.; Marchowski, D.; Wylegała, P.; Chylarecki, P. Monitoring Birds of Poland in 2018–2021. Biul. Monit. Przyr. 2021, 22, 1–80. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, W.; Wójcik, C. Wintering of waterfowl on the Bay of Gdańsk in the season 2003/2004. Not. Orn. 2004, 45, 203–213, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, W.; Janczyszyn, A.; Kośmicki, A.; Trzeciak, H. Waterbird abundance in the Gulf of Gdańsk in the period September 2024–April 2025. Ornis Pol. 2024, 65, 161–170, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetlands International. Waterbird Population Estimates. 2025. Available online: http://wpe.wetlands.org/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Balance Sheets. A Handbook; Food And Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, D.M. Energy expenditure in wild birds. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1997, 56, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.L. Estimates of daily energy expenditure in birds: The time-energy budget as an integrator of laboratory and field studies. Amer. Zool. 1988, 28, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warkentin, I.G.; West, N. Ecological energetics of wintering Merlins Falco columbarius. Physiol. Zool. 1990, 62, 308–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.M.; Barta, Z.; Wikelski, M.; Houston, A.I. A theoretical investigation of the effect of latitude on avian life histories. Am. Nat. 2008, 172, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellebaum, J. Between the Herring Gull Larus argentatus and the bulldozer: Black-headed Gull Larus ridibundus feeding sites on a refuse dump. Ornis Fenn. 2005, 82, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, W.; Betleja, J. Species composition, numbers and age structure of gulls Laridae wintering at rubbish dumps in Poland. Not. Orn. 2007, 48, 11–27, (In Polish with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- Gill, F.B. Ornithology; W.H. Freeman Company: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J.K.; Laubek, B. Disturbance effects of high-speed ferries on wintering sea ducks. Wildfowl 2005, 55, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Schwemmer, P.; Mendel, B.; Sonntag, N.; Dierschke, V.; Garthe, S. Effects of ship traffic on seabirds in offshore waters: Implications for marine conservation and spatial planning. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.J.; Galanidi, M.; Showler, D.A.; Elliott, A.J.; Caldow, R.W.G.; Rees, E.I.S.; Stillman, R.A.; Sutherland, W.J. Distribution and behaviour of common scoter Melanitta nigra relative to prey resources and environmental parameters. Ibis 2006, 148, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Forwarding Company. Baltic Sea Port Transhipments Slightly Up in the First Half of 2025. PFC24. 2025. Available online: https://pfc24.pl/en/baltic-sea-port-transhipments-slightly-up-in-the-first-half-of-2025/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- OECD. Maritime Transportation Costs in the Grains and Oilseeds Sector: Trends, Determinants and Network Analysis; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, V. Variations in the response of Great Crested Grebes Podiceps cristatus to human disturbance—A sign of adaptation? Biol. Conserv. 1989, 49, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minias, P.; Jedlikowski, J.; Włodarczyk, R. Development of urban behaviour is associated with time since urbanization in a reed-nesting waterbird. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

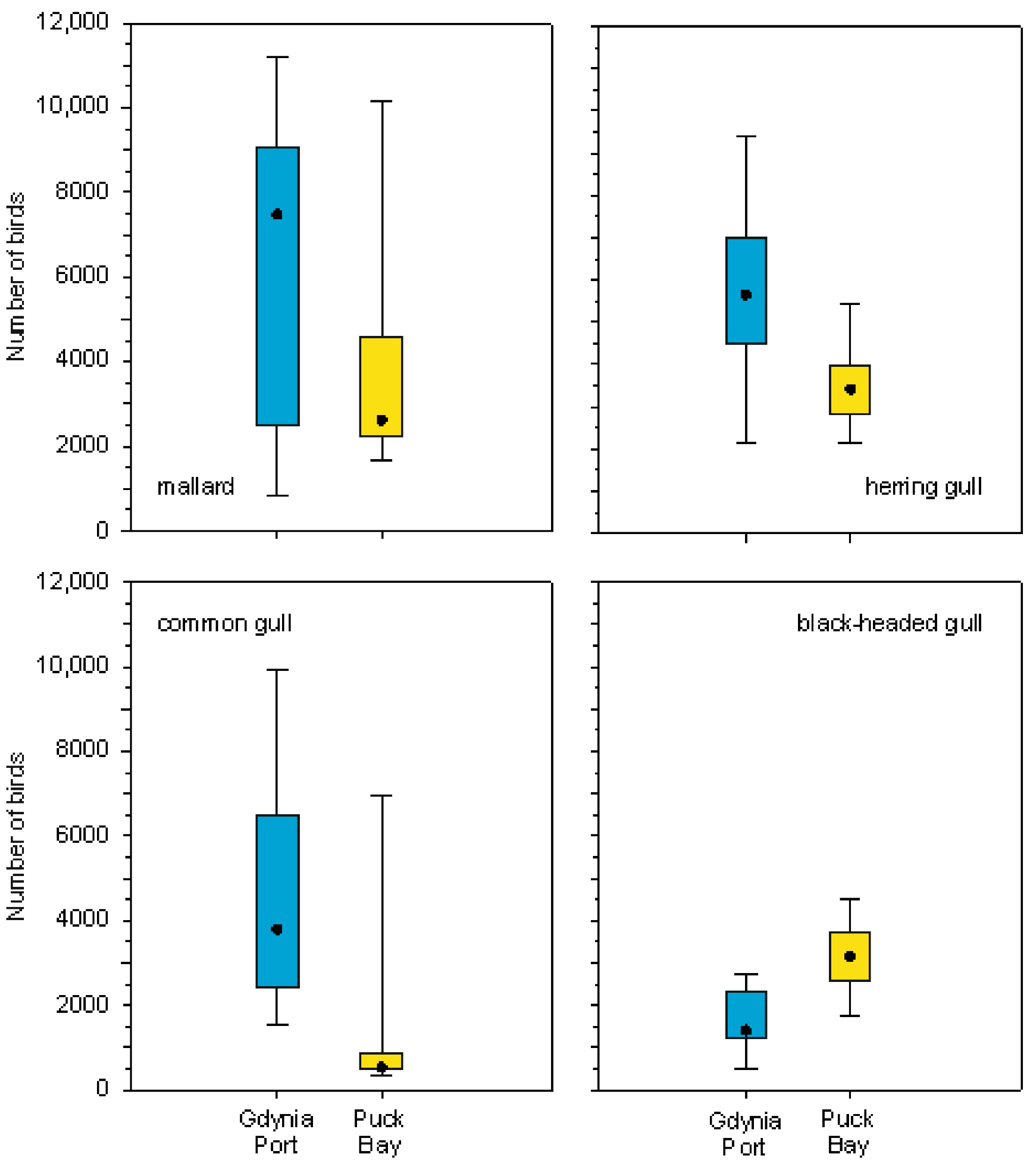

| Species | Mean Number | Maximum Number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port of Gdynia | Puck Bay | Port of Gdynia | Puck Bay | |

| Mallard | 6232 | 3453 | 11,208 | 10,156 |

| Herring gull | 5815 | 3459 | 9372 | 5416 |

| Common gull | 4482 | 1019 | 9927 | 6952 |

| Black-headed gull | 1624 | 3146 | 2749 | 4487 |

| other species | 1208 | 53,661 | 2781 | 78,225 |

| Winter Season | Total Transhipment of Grains and Grain Products (t) | Mean Daily Transhipment of Grains and Grain Products (t) | Mean Daily Acceptable Losses of Grains and Grain Products During Transhipment (t) | Mean Loss of Grain and Grain Products Per Bird (Based on Mean Bird Number) (kg) | Mean Loss of Grain and Grain Products Per Bird (Based on Maximum Bird Number) (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019/20 | 1,213,389 | 13,482 | 27 | 1.5 | 0.8 |

| 2020/21 | 1,343,075 | 14,923 | 30 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| 2021/22 | 937,368 | 10,415 | 21 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| 2022/23 | 1,137,849 | 12,643 | 25 | 1.4 | 0.8 |

| 2023/24 | 1,441,672 | 16,019 | 32 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 2024/25 | 981,852 | 10,909 | 22 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Average | 1,175,868 | 13,065 | 26 | 1.4 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meissner, W. Grain Transhipment Drives Extremely High Winter Waterbird Concentrations in the Port of Gdynia, Southern Baltic. Sustainability 2026, 18, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010335

Meissner W. Grain Transhipment Drives Extremely High Winter Waterbird Concentrations in the Port of Gdynia, Southern Baltic. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010335

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeissner, Włodzimierz. 2026. "Grain Transhipment Drives Extremely High Winter Waterbird Concentrations in the Port of Gdynia, Southern Baltic" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010335

APA StyleMeissner, W. (2026). Grain Transhipment Drives Extremely High Winter Waterbird Concentrations in the Port of Gdynia, Southern Baltic. Sustainability, 18(1), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010335