1. Introduction

The impacts of global warming and climate change are increasingly visible through long-term hydrometeorological observations, where shifts in temperature, precipitation, and evaporation appear as statistically detectable trends across different regions of the world. Identifying such signals within datasets that span several decades is an essential step toward understanding the trajectory of future climate risks. Recent scholarship emphasizes that robust statistical approaches, when applied to records of 50 years or more, can reveal monotonic patterns that would otherwise be obscured by natural variability [

1]. As climate change continues to intensify, the systematic evaluation of these records has become central not only for the scientific community but also for practitioners engaged in water resource management and urban planning.

In this context, the use of empirical trend analysis has expanded considerably in recent decades. Among these tools, the Mann–Kendall (MK) test has become the most widely applied method for detecting monotonic trends in climate series. Its non-parametric nature allows researchers to evaluate long datasets without the limitations of normality assumptions. To complement this, Sen’s slope estimator provides an indication of both the direction and the magnitude of the detected trends, strengthening the interpretation of hydroclimatic variability [

1].

A growing body of literature illustrates the diverse applications of these techniques in climate-sensitive regions. For example, rainfall variability has been identified as a particularly critical factor in shaping water availability and agricultural resilience. Studies in arid and semi-arid regions such as the Sinjar District in northern Iraq demonstrate how trend analyses of 70-year rainfall records can reveal significant long-term declines in precipitation, underscoring the risk of worsening water scarcity and the need for integrated agricultural planning [

2]. Also in the same region, rainfall trends provide essential insights into climate change and water resource stress. Analysis of seven decades of observations through Mann–Kendall, Sen’s slope, and regression techniques revealed a marked annual decline and predominantly negative monthly shifts. October and April alone showed increases, highlighting the uneven climatic pressures shaping local hydrology and agriculture [

3]. Similar approaches applied in Southeast Asia highlight regional contrasts: research in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, detected decreasing rainfall in Mempawah while neighboring areas in Kubu Raya showed increases, reflecting the strong influence of local circulation, topography, and land use on rainfall patterns [

4].

Beyond rainfall, trend detection methods have also been extended to atmospheric and temperature-related variables. In India, spatial analyses of aerosol optical depth (AOD) revealed increasing values across Jharkhand, linked to industrial activity and meteorological drivers, highlighting the combined role of human and climatic factors in shaping air quality [

5]. Similarly, studies integrating modified versions of the Mann–Kendall test with innovative approaches such as Şen’s ITA have provided more reliable assessments of temperature trends by accounting for autocorrelation in long records, as demonstrated in analyses of Oxford’s historical climate data [

6]. Regional applications also confirm the heterogeneity of climate change impacts: research in the Hindu Kush region of Pakistan revealed significant increases in annual and seasonal temperatures, with stronger warming trends in spring and winter, whereas summer signals were more spatially variable [

7].

Investigations in South Asia further underscore the importance of rainfall variability. In Kerala, India, for instance, long-term records revealed a general increase in annual and monsoonal rainfall but declining trends during transitional seasons, indicating both flood risk and dry-period vulnerability [

5]. North-Eastern India, in contrast, exhibited heterogeneous precipitation changes, with some states such as Meghalaya showing positive long-term trends while others, such as Assam, experienced significant declines, reflecting the complex interaction of topography and circulation in monsoon-dominated climates [

8]. Likewise, in the Upper Ganga Basin, long-term rainfall analysis highlighted marked spatial contrasts, with significant decreases in several sub-basins during the monsoon season, raising concerns about agricultural sustainability [

9].

Detecting climate-driven temperature variations is essential for regional sustainability assessments. In their study, Frimpong, Koranteng, & Molkenthin [

10] employs Mann–Kendall and Sen’s slope tests to analyze long-term trends across Pakistan, revealing significant spatial heterogeneity in warming patterns. The findings underscore the necessity of localized adaptation strategies in response to climate variability. Understanding rainfall dynamics is essential for sustainable resource planning in Kerala. An analysis of 1989–2018 rainfall trends in Alappuzha using non-parametric methods reveals statistically significant increases in annual and monsoon precipitation, alongside seasonal declines. These findings highlight shifting hydro-climatic patterns, increased flood risk, and the importance of resilient agricultural strategies under climate variability [

11].

While such studies highlight the global relevance of hydroclimatic trend analysis, a notable gap remains in connecting these findings with urban adaptation frameworks. This is where the concept of Sponge Cities becomes particularly valuable. Developed initially in China, Sponge City applications represent an innovative paradigm in urban water management, emphasizing green infrastructure and ecological design as means of enhancing water retention, reducing runoff, and mitigating urban heat stress [

12]. Despite its growing recognition, the majority of research on Sponge Cities focuses on engineering designs, pilot implementations, or policy analysis, with relatively limited integration of empirical long-term hydroclimatic data as the scientific basis for planning.

The IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report [

13] emphasizes that climate change is already intensifying hydrological extremes, including heavy precipitation events, heatwaves, and prolonged droughts, and highlights the urgent need for cities to strengthen their climate adaptation strategies through the integration of blue-green infrastructure. Recent IPCC assessments increasingly frame nature-based approaches as essential components of urban climate adaptation, particularly in relation to stormwater management and urban resilience.

In parallel with this growing policy emphasis, a substantial body of research has examined the implementation of green-blue infrastructure across diverse geographic and climatic contexts. While terminology varies—ranging from Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) in Europe to the more comprehensive “sponge city” framework developed in East Asia—the underlying hydrological logic remains largely consistent. These approaches seek to restore infiltration, promote temporary on-site storage, and enable the gradual release of stormwater through vegetated and permeable systems, thereby reducing reliance on conventional grey drainage networks.

Recent studies conducted across Europe and the Mediterranean region indicate a gradual convergence toward nature-based and blue-green infrastructure strategies in response to climate-driven hydrological pressures. Several authors describe these approaches as functionally comparable to sponge city practices, even though institutional settings, policy instruments, and implementation pathways differ across regions. For example, the systematic review by Zarei and Shahab [

14] identifies NBS as a central element of contemporary urban green infrastructure planning, while also noting that their performance is closely linked to governance arrangements, long-term financing mechanisms, and inter-sectoral coordination. Their findings further suggest that European and Mediterranean cities have been among the early adopters of NBS, deploying them to address both flood risk and persistent water scarcity.

Comparative research reinforces this conceptual alignment between European SuDS and sponge city applications in China. Lashford et al. [

15] demonstrate that both frameworks rely on shared hydrological principles, including infiltration enhancement, distributed storage, and on-site retention, to alleviate pressure on centralized drainage systems. Although national policy frameworks and design standards vary, the fundamental design logic remains comparable, suggesting that sponge-city-oriented practices are already embedded—at least implicitly—within European stormwater management strategies.

Empirical assessments of hydrological performance further support the relevance of green infrastructure for climate adaptation. A large-scale meta-analysis by Dobkowitz et al. [

16] reports consistent reductions in runoff volume and peak discharge across a range of green infrastructure typologies, including green roofs, bioretention systems, swales, and permeable pavements. Importantly, the study highlights that performance is sensitive to rainfall intensity and antecedent moisture conditions, underscoring the need for climate-responsive and context-specific design—an issue of particular relevance for Mediterranean regions characterized by both intense rainfall events and extended dry periods.

At the urban scale, comparative analyses illustrate how these strategies are being integrated into broader resilience agendas. For instance, Deniz [

17], in a comparative study of Barcelona and İzmir, shows that although institutional capacity and implementation pace differ, both cities increasingly employ blue-green networks to address flooding, heat stress, and ecological degradation. These findings point to the transferability of sponge-city-like principles beyond their original East Asian context.

Taken together, this body of literature indicates that European and Mediterranean cities already employ a range of approaches that are functionally aligned with sponge city strategies, supported by growing empirical evidence on their hydrological and resilience benefits. However, relatively limited attention has been paid to explicitly linking long-term hydroclimatic trends with sponge-city-oriented design considerations, particularly at the regional scale.

Addressing this gap, the present study investigates long-term hydroclimatic patterns in the North Aegean and Marmara regions of Türkiye. These regions provide a suitable case for analysis due to their exposure to Mediterranean-type climate variability and ongoing urban expansion. Using datasets from 12 meteorological stations covering the period 1926–2024, the study applies the Mann–Kendall test and Sen’s slope estimator to assess trends in temperature, precipitation, and evaporation. By relating these trends to sponge city principles, the study offers context-sensitive insights that can inform adaptive urban water management and contributes empirical evidence for integrating long-term climate signals into urban resilience planning in Northwestern Türkiye.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Data Processing

The meteorological datasets were examined for completeness and internal consistency prior to analysis. No physically implausible values, such as negative precipitation or unrealistically high evaporation, were detected; therefore, no records were excluded on the basis of outlier screening. Years with missing observations were identified separately for each station. Given the long temporal coverage of the datasets, missing values were not interpolated to avoid the introduction of artificial variability into the trend analyses. Data homogeneity was evaluated through visual inspection of the daily time series, and no abrupt shifts indicative of station relocation, instrumentation changes, or processing inconsistencies were observed. Accordingly, the datasets were considered suitable for long-term trend assessment.

The processed datasets were then prepared for trend analysis using non-parametric statistical techniques. The raw meteorological data used in this study are subject to institutional restrictions and are available from the Turkish State Meteorological Service (TSMS) upon formal request.

2.2. Mann–Kendall Trend Test

Daily records of temperature, precipitation, and evaporation were aggregated to construct long-term time series for each meteorological station. Standard quality-control procedures were applied to verify physical consistency and data completeness, and no implausible values were identified. Years with missing observations were retained without interpolation, given the extended temporal coverage of the datasets. To limit the influence of short-term variability and serial correlation, trend analyses were performed using daily aggregates derived from the daily observations.

The Mann–Kendall method [

18,

19] assesses whether a time series shows an upward, downward, or no significant trend. The method is derived statistically as:

The statistics of variance has been calculated as:

Here in Equations (1)–(3), Ti and Tj denote the observed values of the analyzed daily series (temperature, precipitation, or evaporation) at time indices i and j (j > i), and n is the total number of observations in the series. The standardized statistic Z is obtained by scaling S with the standard deviation .

Monotonic trends in temperature, precipitation, and evaporation were evaluated using the non-parametric Mann–Kendall (MK) test. The implementation accounts for lag-1 serial autocorrelation and applies a pre-whitening adjustment when required. A two-sided test was used to detect both increasing and decreasing trends. As the analysis focuses on long-term daily behaviour, no seasonal correction was applied. Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 level.

Trend analyses were performed on daily time series derived from daily observations to limit the influence of short-term variability. Trends were examined separately for temperature, precipitation, and evaporation. Accordingly, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was applied, as the objective was to assess variable-specific trends rather than a single joint hypothesis.

2.3. Sen’s Slope Estimator Test

The magnitude of the trend slope in hydrometeorological time series is determined using the Sen’s Slope estimator. Originally introduced by Theil [

20] and subsequently elaborated by Sen [

21], this approach provides a robust, nonparametric estimation of slope and is widely recognized as a reliable alternative to the least-squares method. Trend slope estimation,

Qmed, is obtained from a certain time series (

X1,

X2,...,

Xn) according to Sen’s median slope method as follows:

Trend magnitudes were estimated using Sen’s slope estimator, which provides a robust measure of the daily average rate of change. Slopes are reported in daily units (°C day−1 for temperature and mm day−1 for precipitation and evaporation), allowing for direct comparisons between variables and stations. Calculations are based on long-term comparisons of daily data to ensure consistency and represent long-term regional climate trends. Positive and negative slopes indicate increasing and decreasing trends, respectively.

The methodological contribution of this study lies in linking hydroclimatic trend analysis with urban water management considerations through the Sponge City framework. While non-parametric techniques such as the Mann–Kendall trend test [

22] and Sen’s slope estimator [

23] are well established in hydrology and climatology—particularly for applications related to water resources, floods, and droughts—their explicit integration into urban resilience and planning contexts remains limited. By interpreting long-term climate trends in relation to sponge-city-oriented design principles, the present study extends the application of these methods beyond conventional hydrological analyses.

All statistical analyses were conducted using MATLAB R2024b (Academic Campus License) available at the author’s institution.

2.4. Transformation of Daily Data and Trend Estimation

Daily observations of maximum temperature, precipitation, and evaporation constituted the primary dataset of this study and were compiled into continuous long-term time series for each meteorological station. The daily records were used to characterize short-term variability, extremes, and overall hydroclimatic behaviour, which are essential for understanding event-scale dynamics.

For the purpose of robust trend detection and to reduce the influence of high-frequency variability and potential serial dependence inherent in daily records, trend analyses were conducted using indicators derived from daily data. Daily maximum temperature and evaporation series were analyzed directly, while precipitation trends were evaluated based on daily precipitation records aggregated consistently in time.

The Mann–Kendall (MK) test was applied to detect monotonic trends, and Sen’s slope estimator was used to quantify the magnitude and direction of change. Trend magnitudes are reported in daily units (°C day−1 for temperature and mm day−1 for precipitation and evaporation), with positive and negative values indicating increasing and decreasing trends, respectively. This approach ensures consistency between descriptive statistics derived from daily observations, statistical trend results, and the graphical presentation of daily variability and long-term tendencies.

Accordingly, daily time series and fitted linear trend lines are presented for visual interpretation of variability and extremes, and all statistical significance testing is based on the same daily scale indicators to maintain internal consistency.

2.5. The Concept of Sponge City and Its Connection to Meteorological Data

With the accelerating impacts of climate change, natural disasters are increasingly damaging urban environments and triggering a range of water-related challenges. Flooding, extreme weather events, water scarcity, and pollution are among the most pressing issues. In response, China has introduced the “Sponge City Concept” to mitigate urban flood disasters caused by climate change, rapid urbanization, and inadequate planning, while also reducing the urban heat island effect and fostering sustainable cities [

24].

The Sponge City concept is commonly described through three interrelated principles. First, it emphasizes the preservation of existing urban ecological systems. Natural rivers, lakes, wetlands, ponds, drainage channels, grasslands, and forested areas are maintained to sustain their hydrological functions, with ecological protection treated as a central consideration in urban planning and development. Second, the framework promotes the restoration of degraded ecosystems. Through ecological engineering interventions, impaired systems are rehabilitated to recover ecosystem services and to strengthen the integration of natural elements within urban environments. Third, Sponge City practice incorporates Low Impact Development (LID) strategies for stormwater management. These decentralized, small-scale measures aim to reduce surface runoff and control stormwater pollution and typically include permeable pavements in roads and public spaces, as well as rain gardens and green roofs [

24].

Beyond hydrological regulation, Sponge City interventions also generate thermal co-benefits. Permeable surfaces, green roofs, and interconnected blue-green networks enhance evapotranspiration, reduce surface and near-surface air temperatures, and contribute to the mitigation of urban heat island effects. By linking stormwater management with thermal regulation, Sponge City planning supports flood resilience, urban livability, and climate adaptation, while facilitating cross-sectoral implementation [

25,

26].

Building on these principles, the present study situates Sponge City strategies within a broader analytical framework by explicitly connecting them to hydroclimatic trend analysis. The Sponge City concept, which was systematically developed in China during the 2010s, focuses on enhancing natural water storage capacity in urban landscapes through ecological infrastructure such as wetlands, permeable pavements, and green roofs. Rather than functioning solely as a stormwater control approach, it integrates ecological restoration with flood risk reduction and water reuse objectives, providing a comprehensive model for urban water management under changing climatic conditions [

23].Urban adaptation strategies must be informed by long-term climate variability and trends, especially in regions where precipitation regimes, evaporation rates, and temperature shifts are intensifying due to climate change. Mediterranean-type climates, such as those of the North Aegean and Marmara regions, are particularly sensitive, with rainfall patterns becoming increasingly erratic and evaporation rates rising under warming conditions. Yet, existing literature on Sponge Cities has predominantly focused on East Asia, especially China, where policy frameworks and large-scale infrastructure programs have driven research agendas. Comparative studies in Europe and the Mediterranean remain relatively scarce, and those that do exist often rely on short-term data or scenario-based modeling rather than empirical century-long climate records.

The main motivation of this study, therefore, lies in its methodological bridging of climatology and urban water management. By applying the MK test and Sen’s Slope Estimator to precipitation, temperature, and evaporation data spanning 1926–2024 from 12 meteorological stations, the research generates statistically robust insights into hydroclimatic dynamics. These findings are also translated into practical recommendations for Sponge City applications tailored to the North Aegean and Marmara contexts.

Furthermore, this approach introduces a level of regional specificity that is often missing in broader climate adaptation frameworks. The inclusion of both coastal and inland stations captures spatial heterogeneity across the study area, enabling nuanced considerations of flood risk, drought vulnerability, and water resource pressures. Such detail is critical, as Sponge City strategies must be adapted to local climatic and hydrological realities rather than applied in a generic or uniform manner.

In summary, the study addresses a key literature gap by operationalizing long-term meteorological analysis as a decision-support tool for Sponge City planning. This methodological innovation offers dual contributions: it enriches the hydrological literature by expanding the applied relevance of trend analysis methods, and it advances urban sustainability research by grounding Sponge City strategies in empirical climatic evidence. The resulting framework provides a replicable model for integrating climate data into resilience planning, with potential applicability beyond Türkiye to other regions facing similar hydroclimatic and urbanization challenges.

3. Regional Context of the North Aegean and Marmara Case Study

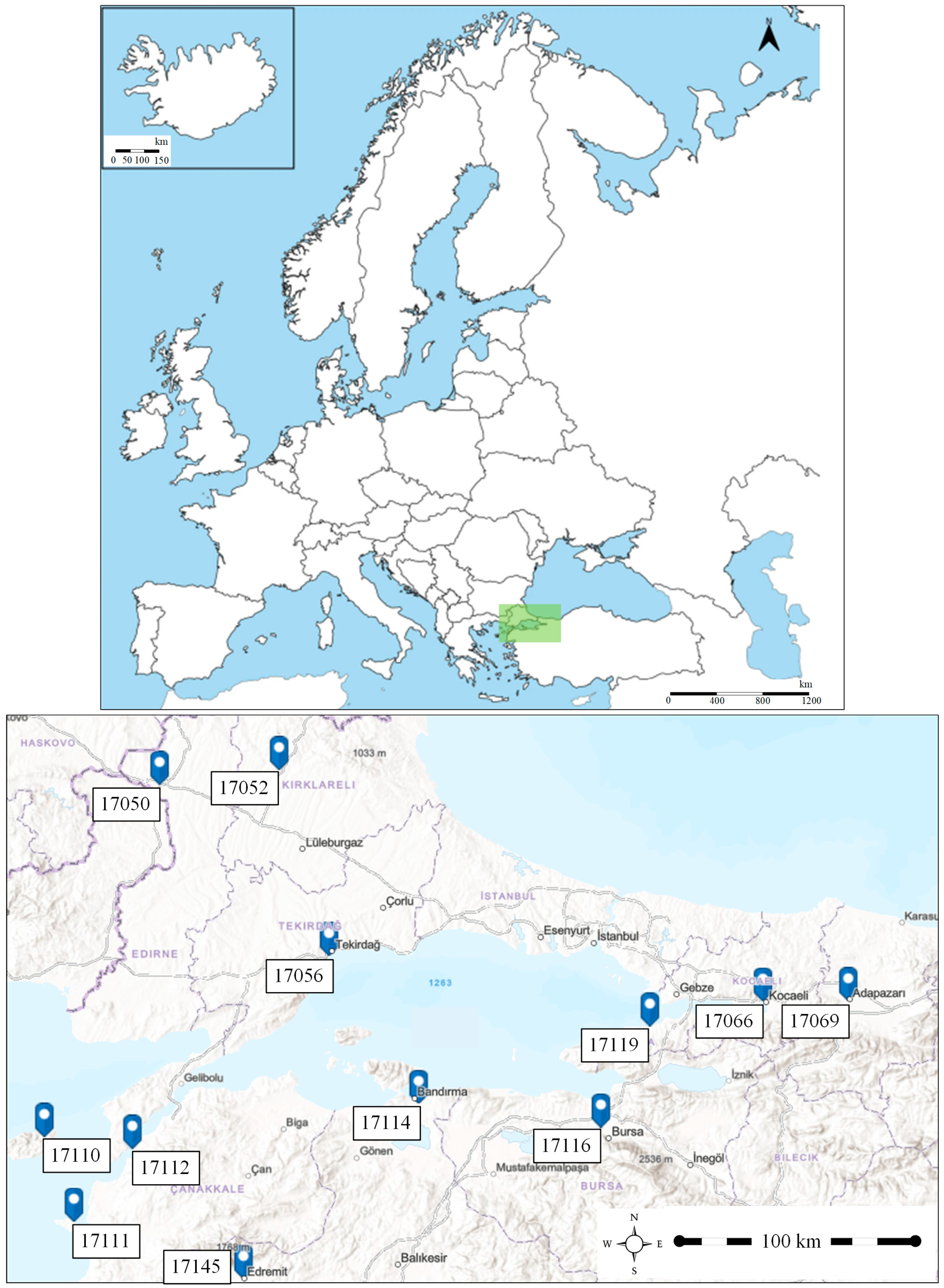

The research focuses on the North Aegean and Marmara regions of Türkiye, areas characterized by diverse climatic conditions, rapid urbanization, and ecological sensitivity. To capture regional hydroclimatic variability, 12 meteorological stations were selected based on spatial distribution and the temporal availability of long-term data. These stations include both coastal locations (e.g., Gökçeada, Bozcaada, Bandırma) and inland sites (e.g., Bursa, Sakarya, Edirne), thereby representing a wide range of climatic and geographical conditions relevant to the study objectives. The primary data were obtained from the official archives of the Turkish State Meteorological Service (TSMS). Data availability differs among stations; start years range between 1926 and 1959. Longest and most continuous records are available for Edirne, Kocaeli, Çanakkale, Bursa, and Yalova stations, where precipitation and temperature data extend back to the late 1920s or early 1930s. In contrast, Kırklareli, Gökçeada, Bozcaada, and Edremit stations provide comparatively shorter records beginning in the 1950s–1960s. Evaporation data are generally available from the mid-20th century onwards, while Gökçeada and Bozcaada lack evaporation observations. Detailed information on station numbers, coordinates, and data availability for each parameter is presented in

Table 1.

The North Aegean and Marmara regions provide an appropriate geographical and climatic setting for interpreting the long-term hydroclimatic trends examined in this study. Positioning the case-study section after the methodological framework allows the subsequent results to be evaluated within a clearly defined context rather than introducing regional details prematurely.

Both regions are characterized by Mediterranean-influenced climatic conditions, with dry summers, irregular precipitation regimes, and an increasing occurrence of short-duration, high-intensity rainfall events. Ongoing urban expansion and the growth of impervious surfaces have increased the vulnerability of coastal cities to pluvial flooding. At the same time, recurrent summer droughts and high evaporation rates place additional pressure on urban water resources. Together, these factors make the regions well suited for examining how long-term daily trends in temperature, precipitation, and evaporation can be translated into design considerations relevant to sponge-city-oriented strategies.

By outlining the key physical and urban characteristics at this stage, the interpretation of the trend results in the following section becomes more coherent, and the implications for sustainable urban water management can be more directly articulated. The study area and the locations of meteorological stations are shown in

Figure 1.

4. Results

The statistical overview of daily maximum temperatures, daily maximum precipitation, and daily total maximum open surface evaporation data across the 12 meteorological stations provides important insights into the hydroclimatic diversity of the North Aegean and Marmara regions in

Table 2. Daily time series and corresponding linear trend lines for individual stations are provided in

Supplementary Materials, Figures S1–S6 for detailed visual reference. Linear trend lines shown in

Figures S1–S6 were obtained using a least-squares polynomial fit (first order) implemented via MATLAB polyfit and polyval functions and are intended for visual interpretation only. Statistical significance of the trends was evaluated separately using the Mann–Kendall test; no significance markers are shown in the figure.

Edirne shows a wide thermal range from –10.9 °C to 44.1 °C, with a mean of 19.93 °C and high variability (SD = 10.01). Precipitation is relatively moderate (mean 5.52 mm), but extreme daily events reach 119.6 mm, underscoring flood risk. Evaporation averages 4.07 mm, consistent with semi-continental influences.

Kırklareli has slightly cooler conditions (mean 19.06 °C), with a maximum precipitation event of 128.3 mm, exceeding Edirne. Evaporation levels (mean 4.45 mm) are somewhat higher, reflecting inland exposure.

Tekirdağ, a coastal station, records milder temperatures (mean 18.03 °C) and lower precipitation averages (3.32 mm). However, the maximum daily precipitation (140.1 mm) demonstrates susceptibility to coastal storm events. Evaporation (4.19 mm) is consistent with maritime influences.

Kocaeli and Sakarya, both located in the eastern Marmara basin, exhibit high maximum temperatures (44.1 °C and 44.0 °C, respectively) and strong precipitation variability. Kocaeli reports the highest daily maximum precipitation among mainland stations (169.4 mm), while Sakarya shows comparable precipitation intensity but lower evaporation averages (3.75 mm).

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for daily maximum temperature, daily precipitation, and daily evaporation across the North Aegean and Marmara regions and provides a baseline for interpreting the trend results summarized in

Table 3. The statistics indicate substantial spatial variability and the presence of hydroclimatic extremes that are not fully represented by mean values alone.

Daily maximum temperature shows relatively high mean values across all stations, generally between 18 and 20 °C, while maximum values exceed 40 °C at several locations. The coexistence of elevated means, broad ranges, and high upper extremes reflects a pronounced thermal background. This pattern is consistent with the statistically significant warming trends reported in

Table 3 and suggests that even moderate positive temperature trends may be associated with an increased occurrence of heat extremes.

Precipitation statistics are characterized by low to moderate mean daily values alongside very high maximum rainfall amounts, in some cases exceeding 200 mm. This contrast indicates a rainfall regime dominated by episodic, high-intensity events. When considered together with the trend results in

Table 3, which show both increasing and decreasing long-term tendencies, the descriptive statistics point to changes in the temporal distribution of precipitation rather than uniform shifts in total amounts. Such patterns are particularly relevant for flood risk in coastal and highly urbanized catchments.

Evaporation statistics further illustrate the heterogeneous hydroclimatic response across the region. Several mainland stations exhibit relatively high mean daily evaporation values combined with substantial variability. These characteristics are consistent with the mixed, and in many cases statistically significant, evaporation trends identified in

Table 3, reflecting the combined effects of temperature increases and local atmospheric conditions. Evaporation data are unavailable for Gökçeada and Bozcaada; consequently, these stations are excluded from evaporation-related analyses, which constitutes a limitation of the dataset.

Overall, the descriptive statistics in

Table 2 depict a hydroclimatic regime marked by high variability and pronounced extremes. This baseline context supports the interpretation of the statistically significant trends reported in

Table 3 and highlights the importance of adaptive urban water management approaches capable of responding to both intense rainfall events and increasing atmospheric water demand.

Çanakkale mirrors island-like moderation, with a mean temperature of 19.81 °C and a mean precipitation of 3.93 mm. Evaporation is relatively high (5.44 mm), highlighting strong summer dryness. Gökçeada and Bozcaada, island stations, display moderated temperatures (means around 19 °C) and lower variability. Precipitation extremes, however, are remarkable: Bozcaada reports the highest single-day precipitation of all stations (243.4 mm), emphasizing the role of maritime cyclonic activity. Evaporation data are unavailable for these sites, representing a limitation. Bandırma shares similarities, with moderate temperature (18.91 °C) and a maximum daily rainfall identical to Bozcaada (243.4 mm). Evaporation averages 4.59 mm, indicating balanced coastal-inland dynamics. Bursa, an inland lowland station, shows higher mean temperatures (20.52 °C) and strong precipitation extremes (229 mm). Evaporation (4.24 mm) reflects inland continentality, reinforcing vulnerability to both heat and storm events. Yalova, a coastal Marmara station, records moderated thermal conditions (mean 19.21 °C). Precipitation extremes (181.9 mm) are significant, but evaporation averages are lowest among coastal sites (3.29 mm), suggesting high soil moisture retention potential. Edremit, at the southern Aegean margin, demonstrates the warmest mean (22.42 °C). Although precipitation is moderate (mean 3.88 mm), evaporation is among the highest (5.12 mm), confirming strong evaporative demand and heightened drought risk. This station-by-station evaluation highlights a clear climatic gradient: inland and southern stations (Edirne, Bursa, Edremit) experience stronger continentality with higher temperature variability and evaporation, while coastal and island stations (Tekirdağ, Gökçeada, Bozcaada, Yalova) are more moderated but face extreme precipitation events. These variations underline the necessity of localized Sponge City strategies: flood mitigation in island/coastal zones and water retention in inland/drought-prone regions.

The Mann–Kendall trend test and Sen’s slope estimator results presented in

Table 3, together with the descriptive statistics summarized in

Table 2, provide a coherent assessment of long-term climatic changes across the North Aegean and Marmara regions. The analysis reveals statistically significant trends in temperature, precipitation, and evaporation at most stations, although the magnitude and direction of change vary spatially.

Temperature trends indicate a consistent and statistically significant increase across all stations. Mann–Kendall test results yield very low

p-values in each case, supporting the rejection of the null hypothesis of no trend. Correspondingly, positive Sen’s slope estimates, ranging from 2.871 × 10

−5 to 1.08 × 10

−3 °C day

−1, point to a region-wide warming signal. These findings are consistent with the descriptive statistics presented in

Table 2, where mean daily maximum temperatures are close to or exceed 19–20 °C at several stations and observed extremes surpass 40 °C. Together, the trend results and descriptive characteristics indicate an intensification of thermal conditions, which is relevant for urban heat exposure and water demand.

Precipitation trends display pronounced spatial variability. Although most stations exhibit statistically significant trends (

p < 0.05), the direction of change differs across the study area. Negative Sen’s slope values at stations such as Bursa (−2.607 × 10

−4 mm day

-1), Sakarya (−2.331 × 10

−4 mm day

−1), and Çanakkale (−2.275 × 10

−4 mm day

−1) suggest declining long-term precipitation tendencies. Edirne does not show a statistically decreasing or increasing trend, underscoring local-scale variability. When considered alongside the descriptive statistics in

Table 2, which report daily precipitation extremes exceeding 200 mm at several coastal stations, these results point to changes in rainfall distribution toward more episodic and intense events, with implications for flood risk.

Evaporation trends further reflect the heterogeneous hydroclimatic response of the region. Statistically significant trends are detected at most mainland stations, with both positive and negative Sen’s slope values observed. Increasing evaporation is evident at stations such as Tekirdağ (1.654 × 10

−4 mm day

−1) and Çanakkale (6.875 × 10

−5 mm day

−1), consistent with their relatively high mean evaporation values reported in

Table 2. In contrast, decreasing evaporation trends are identified at Bandırma (−1.684 × 10

−4 mm day

−1) and Yalova (−5.026 × 10

−5 mm day

−1). Evaporation data are unavailable for Gökçeada and Bozcaada; these stations are therefore excluded from the evaporation trend analysis. The coexistence of rising temperatures and increasing evaporation at several locations suggests an intensification of atmospheric water demand.

Overall, the results summarized in

Table 3 describe a hydroclimatic setting characterized by widespread warming, spatially variable precipitation trends, and significant changes in evaporation dynamics. Taken together, these patterns indicate an increased potential for both drought conditions during extended warm periods and flooding associated with intense rainfall events. Such combined pressures highlight the relevance of adaptive urban water management strategies, including sponge-city-oriented approaches that emphasize stormwater retention, infiltration, and controlled release under changing climatic conditions.

Figure 2 illustrates daily variability together with fitted trend lines for selected stations in the North Aegean and Marmara regions, complementing the statistical results presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3. While

Table 2 documents pronounced day-to-day fluctuations and extreme values—particularly for temperature and precipitation—

Figure 2 places this short-term variability within the context of the long-term tendencies identified by the Mann–Kendall test and Sen’s slope estimator (

Table 3). For temperature, the consistently upward orientation of the fitted trend lines aligns with the uniformly positive and statistically significant daily slopes, indicating that observed daily extremes exceeding 40 °C occur within a broader pattern of regional warming. In the case of precipitation,

Figure 2 reveals highly irregular daily patterns with sporadic extreme events, supporting the interpretation that mixed or weak daily trends in

Table 3 coexist with a redistribution of rainfall toward fewer but more intense episodes, as suggested by the high daily maxima in

Table 2. Similarly, the evaporation time series display substantial intra-daily variability, while the direction of the fitted trend lines corresponds to the station-specific Sen’s slope estimates. Taken together,

Figure 2 bridges descriptive and inferential analyses by showing how statistically derived long-term trends emerge from highly variable daily processes, thereby reinforcing the consistency between

Table 2 and

Table 3 and providing a coherent basis for subsequent discussion of hydrological risk and urban water management implications.

5. Discussion

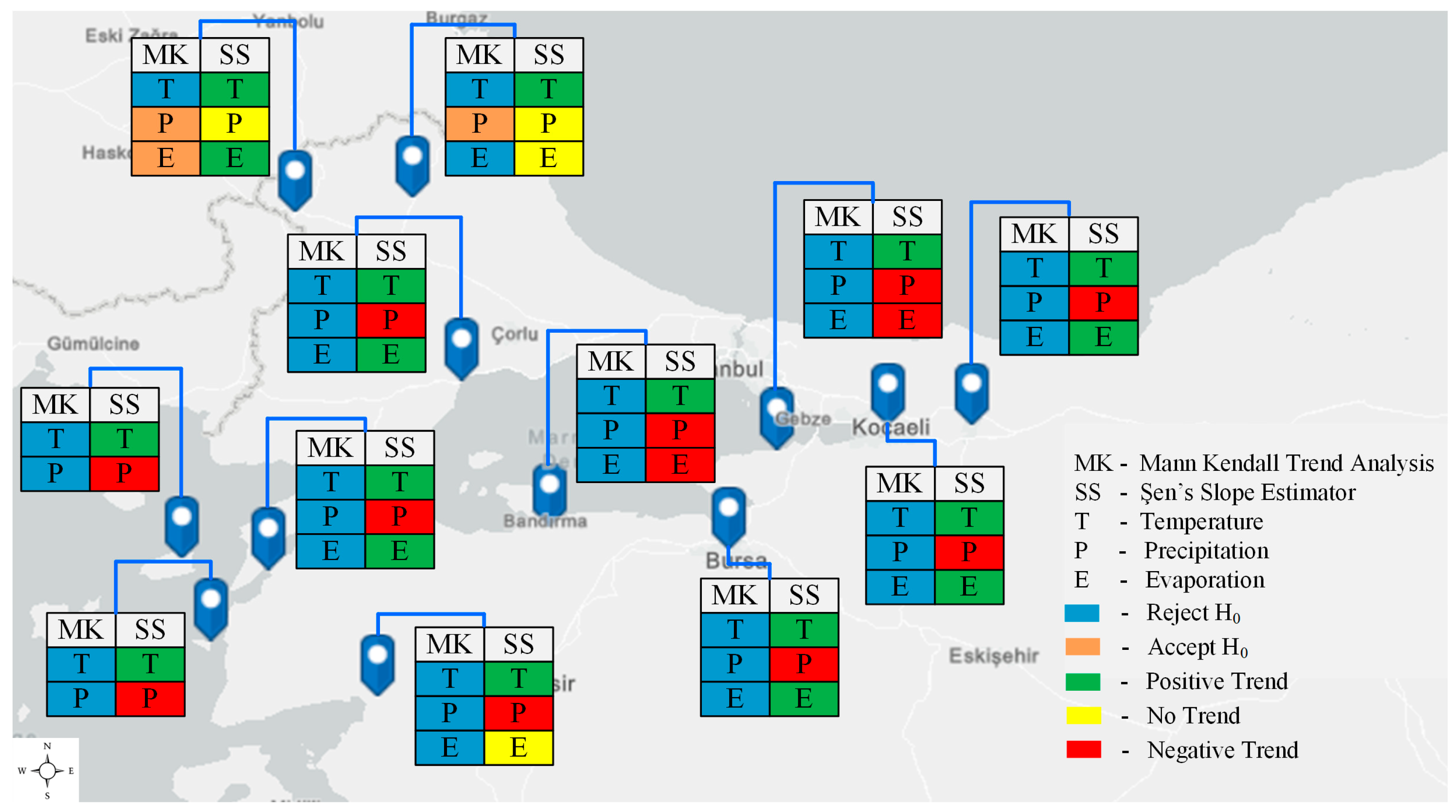

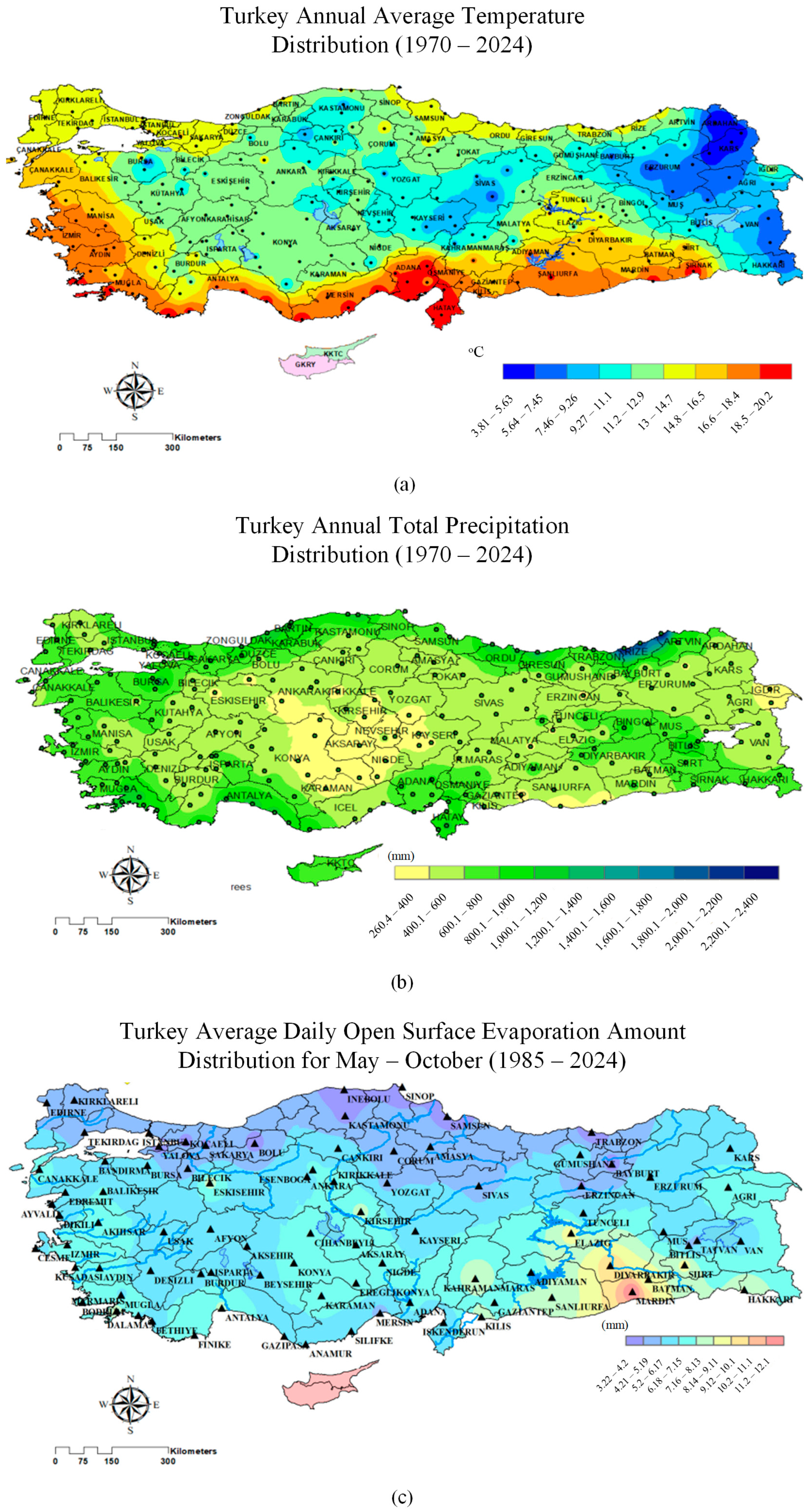

The results of this study were evaluated using

Table 3 together with

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 in order to understand hydroclimatic change at different spatial scales.

Table 3 provides the core statistical evidence by quantifying long-term trends in temperature, precipitation, and evaporation based on daily time series.

Figure 2 presents these trends visually for selected stations, allowing regional similarities and contrasts to be observed.

Figure 3 places the station-based findings within the broader climatological setting of Türkiye using national datasets provided by the Turkish State Meteorological Service. Considered together, these elements suggest that the detected trends reflect broader regional patterns rather than isolated local effects.

Examining daily hydroclimatic variability alongside long-term daily trends offers additional insight into climate-related risks. Although the statistical analyses rely on daily indicators, the daily data reveal pronounced variability and the presence of extreme events. Such extremes directly affect urban hydrological processes, particularly runoff generation and drainage performance. Previous studies have similarly emphasized that climate change impacts in urban areas are increasingly associated with changes in variability and event intensity rather than steady shifts in mean conditions [

27,

28].

In the North Aegean and Marmara regions, statistically significant warming trends coincide with very high daily maximum temperatures at several stations. This combination has been reported for other Mediterranean and transitional climate zones, where relatively small long-term temperature trends are linked to a disproportionate increase in heat extremes [

29]. From an urban water management perspective, rising temperatures are relevant not only for heat stress but also for their influence on evaporation rates and atmospheric water demand. These processes affect the long-term functioning of green and blue infrastructure, particularly during extended dry periods.

Precipitation patterns show greater spatial complexity. Daily precipitation trends vary in both magnitude and direction across the study area, and some stations do not exhibit statistically significant changes. At the same time, daily precipitation records include very high rainfall maxima, indicating the occurrence of intense short-duration events. Similar behaviour has been documented in European urban catchments, where total daily rainfall remains relatively stable while pluvial flood risk increases due to rainfall concentration into fewer, more intense storms [

30]. This distinction is important for urban drainage design, which is often governed by peak intensities rather than daily totals.

Evaporation trends further illustrate the heterogeneous hydroclimatic response of the region. Both increasing and decreasing tendencies are observed, depending on station location and local conditions. At some sites, rising temperatures coincide with increasing evaporation, suggesting enhanced atmospheric water demand. At others, decreasing evaporation trends are detected, indicating that additional factors such as wind conditions or humidity may play a role. These mixed responses highlight that evaporation cannot be inferred from temperature trends alone and should be considered explicitly in urban water management analyses.

Taken together, the results indicate a coupled system of hydroclimatic pressures characterized by widespread warming, variable precipitation behaviour, and significant changes in evaporation dynamics. Such conditions imply an increased likelihood of both water scarcity during prolonged warm periods and flooding associated with intense rainfall events. Addressing these dual risks poses challenges for conventional grey infrastructure, which is typically designed for stationary climatic conditions.

Within this context, the Sponge City concept provides a useful framework for interpreting the results from an urban water management perspective. Comparable to Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems and other nature-based solutions, Sponge City strategies aim to manage both extremes and long-term changes through decentralized storage, infiltration, and delayed release mechanisms [

24,

31]. The presence of intense daily rainfall events supports the need for retention and infiltration systems capable of handling high peak loads, while observed warming and evaporation trends underline the importance of maintaining soil moisture and vegetation performance during dry periods.

In this sense, sponge-city-oriented approaches offer a practical pathway for linking long-term climate evidence with urban infrastructure design. Empirical studies show that systems combining distributed storage, infiltration, and delayed discharge can reduce peak runoff and improve system resilience when aligned with evolving rainfall regimes [

32]. The hydroclimatic trends identified in the present study therefore provide a basis for informing context-specific design choices related to storage capacity, infiltration performance, and return periods in Mediterranean and transitional climate regions.

6. Conclusions

Long-term hydroclimatic analyses reveal profound and statistically significant changes across the North Aegean and Marmara regions. Mann–Kendall and Sen’s slope tests confirm pervasive warming trends, with nearly all stations recording increases in maximum daily temperatures. Bursa, Sakarya, and Çanakkale display the strongest slopes, while several locations now register extreme values above 44 °C, signaling intensifying heat waves and heightened urban heat stress.

Precipitation patterns are more spatially heterogeneous but equally concerning. Coastal and island stations such as Bozcaada and Bursa report single-day rainfall exceeding 200 mm, while most stations show negative slopes. In contrast, Edirne displays no significant trends, highlighting localized variability. Collectively, these findings suggest a marked increase in short-duration, high-intensity rainfall events that elevate flash flood risk, particularly in urbanized coastal settings.

Evaporation trends add another layer of complexity. Tekirdağ and Çanakkale exhibit significant upward slopes, confirming heightened evaporative demand under warming conditions, while Bandırma and Yalova show declines, likely reflecting local land-use and microclimatic influences. The coexistence of increasing temperatures, intensifying rainfall, and divergent evaporation regimes signals a destabilized hydrological cycle in which drought and flooding risks alternate in close succession.

These shifts expose the limitations of traditional grey infrastructure, which was designed for more stable climatic baselines. Drainage systems risk being overwhelmed by short, intense rainfall, while storage capacity is insufficient during prolonged dry spells. Urban water management must transition toward systems that buffer extremes, capture surplus water during storms, and store or reuse it during droughts.

Sponge City principles directly address the challenges identified in this study. Permeable pavements, bioswales, wetlands, and green roofs reduce surface runoff, increase infiltration, and provide distributed storage. Importantly, they also moderate urban heat islands, enhance biodiversity, and improve air quality. Given the region’s exposure to both hydrological extremes and thermal stress, the adoption of Sponge City strategies is not optional but imperative.

Policy frameworks must embed Sponge City design into urban development standards. This includes:

Mandatory integration of green infrastructure in new projects and retrofits.

Priority retrofitting in flood-prone districts and water-stressed inland areas.

Incentive schemes for developers and municipalities to encourage adoption.

Basin-wide coordination across municipalities to address hydrological risks that extend beyond administrative boundaries.

Monitoring networks to evaluate intervention performance under local climatic conditions.

By combining green and grey systems in a unified framework, cities can improve resilience to both excess water and scarcity.

The long-term trends identified in daily temperature, precipitation and evaporation for the North Aegean and Marmara regions underline the need to convert climatic signals into explicit design criteria for Sponge City–oriented interventions. Within the Sponge City framework, stormwater control is achieved by combining storage, infiltration, detention and controlled discharge in distributed systems such as green roofs, bioretention cells, permeable pavements and shallow detention zones [

24].

Rather than relying on stationary design assumptions, these systems are expected to respond to intensifying short-duration rainfall and warming trends by adjusting three key parameters: event-based storage capacity, effective infiltration (or media hydraulic conductivity) and the choice of design storms and associated return periods [

32].

Recent reviews on sustainable stormwater management and bioretention emphasize that hydraulic performance is highly sensitive to media properties, internal water storage zones and surface ponding depth, all of which control both infiltration capacity and drawdown time [

33].

In parallel, meta-analyses of green infrastructure and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) show that well-designed systems routinely achieve substantial runoff reductions, with typical ranges on the order of 30–60% depending on infrastructure type, scale and rainfall regime [

16,

34].

These findings imply that trend magnitudes of precipitation and evaporation are not only statistically relevant but can directly inform design targets for storage depth, infiltration layer thickness and acceptable emptying times under future hydroclimatic conditions.

In this context, the trend analysis performed here provides boundary conditions for Sponge City design in the North Aegean and Marmara regions: intensified wet-season extremes argue for higher local storage and infiltration capacities in bioretention and permeable surfaces, while concurrent increases in temperature and seasonal evaporation favour multifunctional blue-green systems that can retain water during wet periods and release it gradually through evapotranspiration during drier intervals.

Taken together, the literature indicates that Sponge City strategies offer a technically robust and climate-responsive framework in which long-term hydroclimatic trends, such as those quantified in this study, can be translated into site-specific targets for storage capacity, effective infiltration and updated design storms—thus linking statistical evidence directly to urban water-sensitive planning.

This study demonstrates the scientific value of linking century-scale meteorological evidence with urban resilience frameworks. By applying robust non-parametric statistical methods, it extends their use beyond climatology into applied urban water management. Future research should focus on:

Evaluating the performance of Sponge City measures under regional climatic extremes.

Conducting cost–benefit analyses to support policy uptake.

Downscaling global climate projections to city-level planning horizons.

Investigating the co-benefits of Sponge City interventions, including thermal comfort and ecosystem services.

The long-term trends identified in this study have direct relevance for the design and configuration of sponge-city-oriented interventions under Mediterranean and transitional climate conditions. The coexistence of rising temperatures and increasing evaporation at several stations suggests that green-blue infrastructure systems should prioritize water retention to sustain evapotranspiration during extended dry periods. Evidence from European and Mediterranean applications indicates that decentralized systems with moderate storage depths—typically on the order of several tens of millimetres—can provide a balanced response by supporting both runoff control and water availability.

At the same time, the spatially heterogeneous precipitation trends identified across the study area point to a tendency toward more temporally concentrated rainfall events. This behaviour supports the adoption of intermediate design return periods, commonly in the range of 5–10 years, rather than relying solely on short-duration design storms. The regional contrasts revealed by the trend analyses further highlight the importance of spatially differentiated sponge city configurations, in which permeable pavements, green roofs, and bioretention elements are combined according to local conditions rather than applied uniformly. Previous European experience suggests that allocating approximately one-third to one-half of urban surfaces to permeable or vegetated solutions can substantially improve hydrological performance while remaining compatible with existing urban form.

Overall, these findings illustrate how statistically derived hydroclimatic trends can be interpreted in a design-oriented manner, linking quantitative climate analysis with context-sensitive urban water management strategies.

The North Aegean and Marmara regions are increasingly characterized by heightened hydrological variability, with both prolonged dry periods and intense rainfall events becoming more prominent. Within this context, the results suggest that conventional incremental adaptation measures may be insufficient to address emerging risks. Instead, integrated approaches based on sponge city principles offer a viable pathway for enhancing urban resilience by accommodating both long-term climatic shifts and short-term extremes. Embedding such approaches within urban planning and policy frameworks can support more adaptive, resilient, and sustainable urban water systems under changing climatic conditions.