Open Municipal Markets as Networked Ecosystems for Resilient Food Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Role of Open Municipal Markets in Urban Food Systems

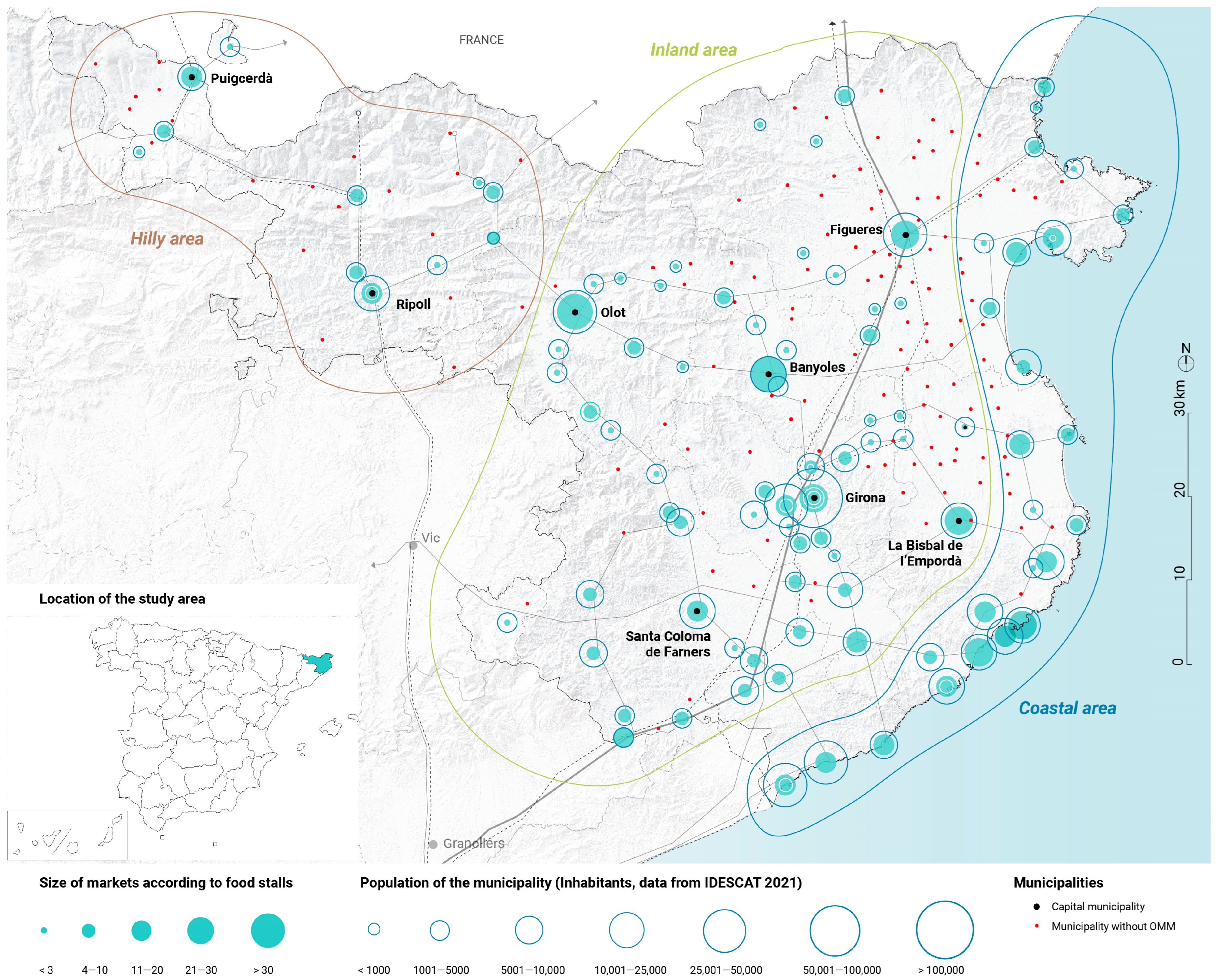

1.2. The Case Study: OMM Ecosystem in the Province of Girona, Spain

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework

- Phase 1: Sample selection, data collection and processing. Markets were characterized and selected to reflect diversity in size, the municipal profile, tourism intensity and levels of institutional support.

- Phase 2: Development and refinement of a set of indicators to define key metrics and to group markets into functional geographical areas. These facilitated a comparative analysis of how OMMs operate as logistical and social nodes, highlighting their role in enhancing proximity-based distribution.

- Phase 3: Data analysis and spatial analysis implementing the proposed indicators.

2.2. Phase 1: Data Collection and Markets Characterization

2.2.1. Data Collection

2.2.2. Focusing on Stallholders

- Resellers (R) commercialize products acquired from intermediaries such as wholesale markets (e.g., MercaBarcelona, MercaGirona or MercaVallès) or directly from specialized suppliers.

- Producer-resellers (PR) offer a combination of purchased and self-produced goods, with the latter accounting for up to 60% of the total number of products sold.

- Producers (P) primarily sell their own harvest, representing 60% or more of the products available at their stall.

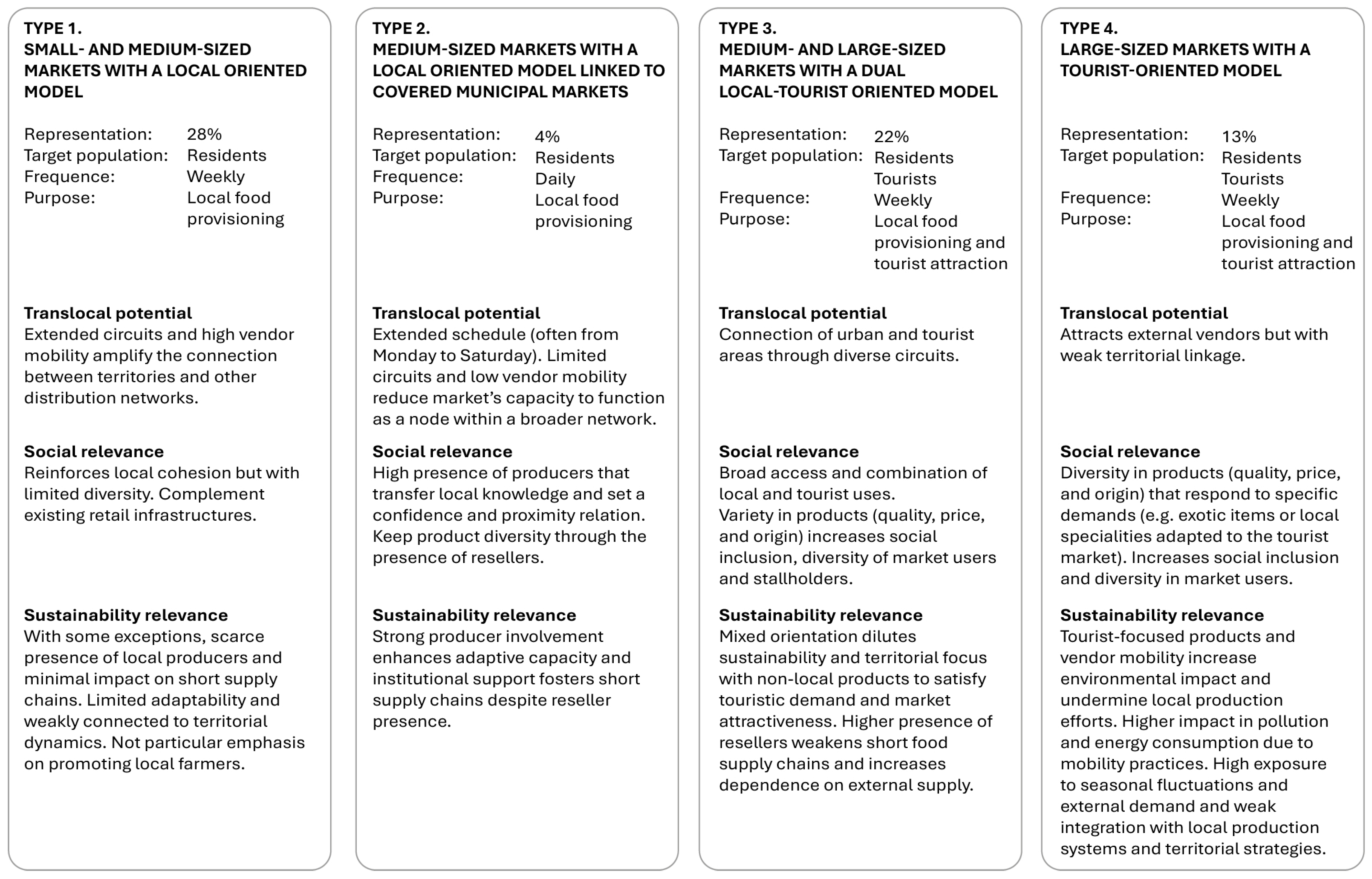

2.2.3. Characterization of Market Types

2.3. Phase 2: Determining Market Mobility Indicators

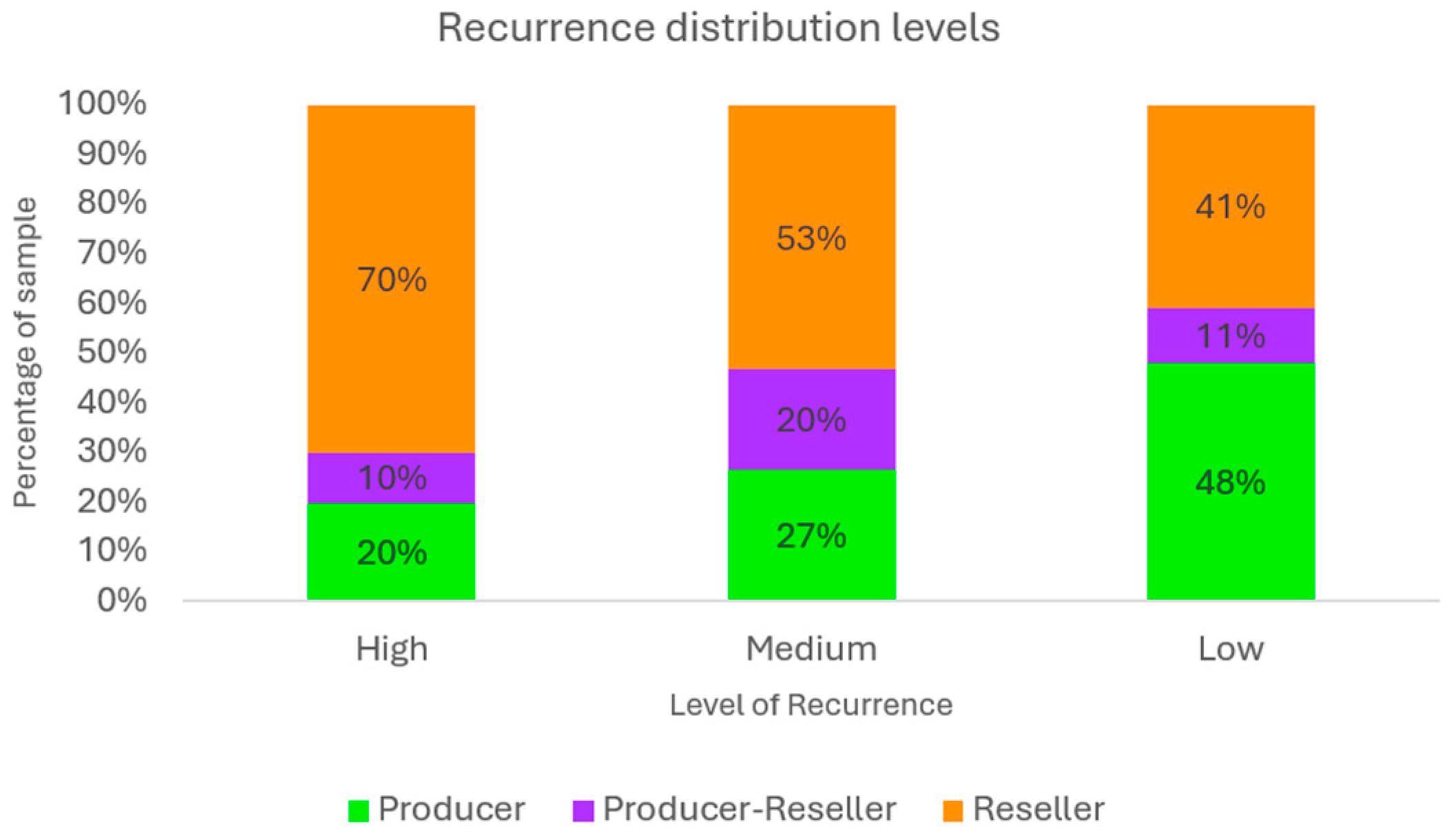

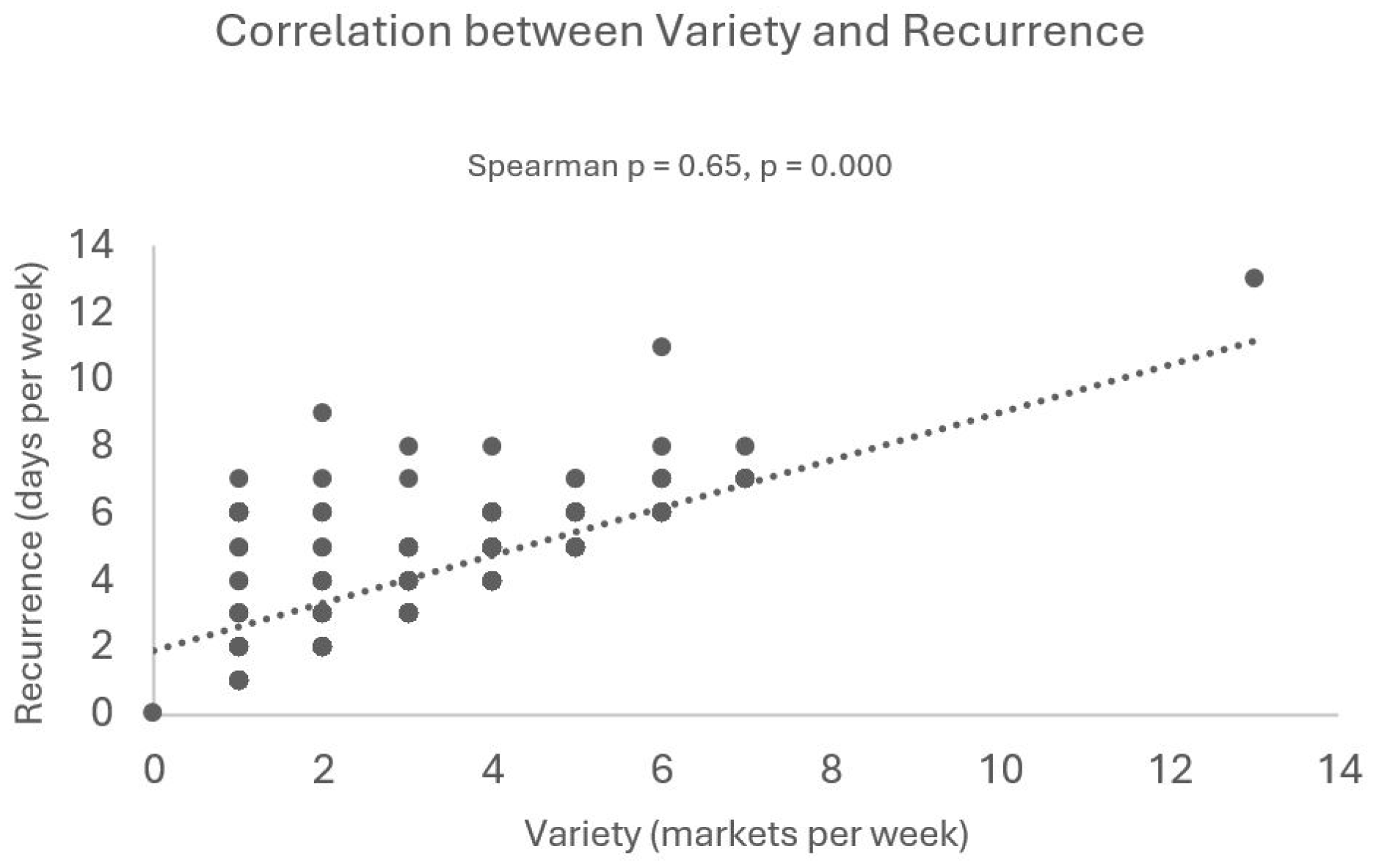

- Recurrence refers to the number of days per week that stallholders are active in markets; this indicator helps in assessing the intensity of their engagement and may also suggest whether they perform roles beyond vending. It provides insight into their dependency on the local market system and their potential contribution to consistent, place-based food provisioning. This resonates with relational theories of place, as the repeated presence of vendors reinforces the continuous socio-spatial production of markets. Recurrence is classified as Low (up to three days), Medium (four days) or High (five or more days per week).

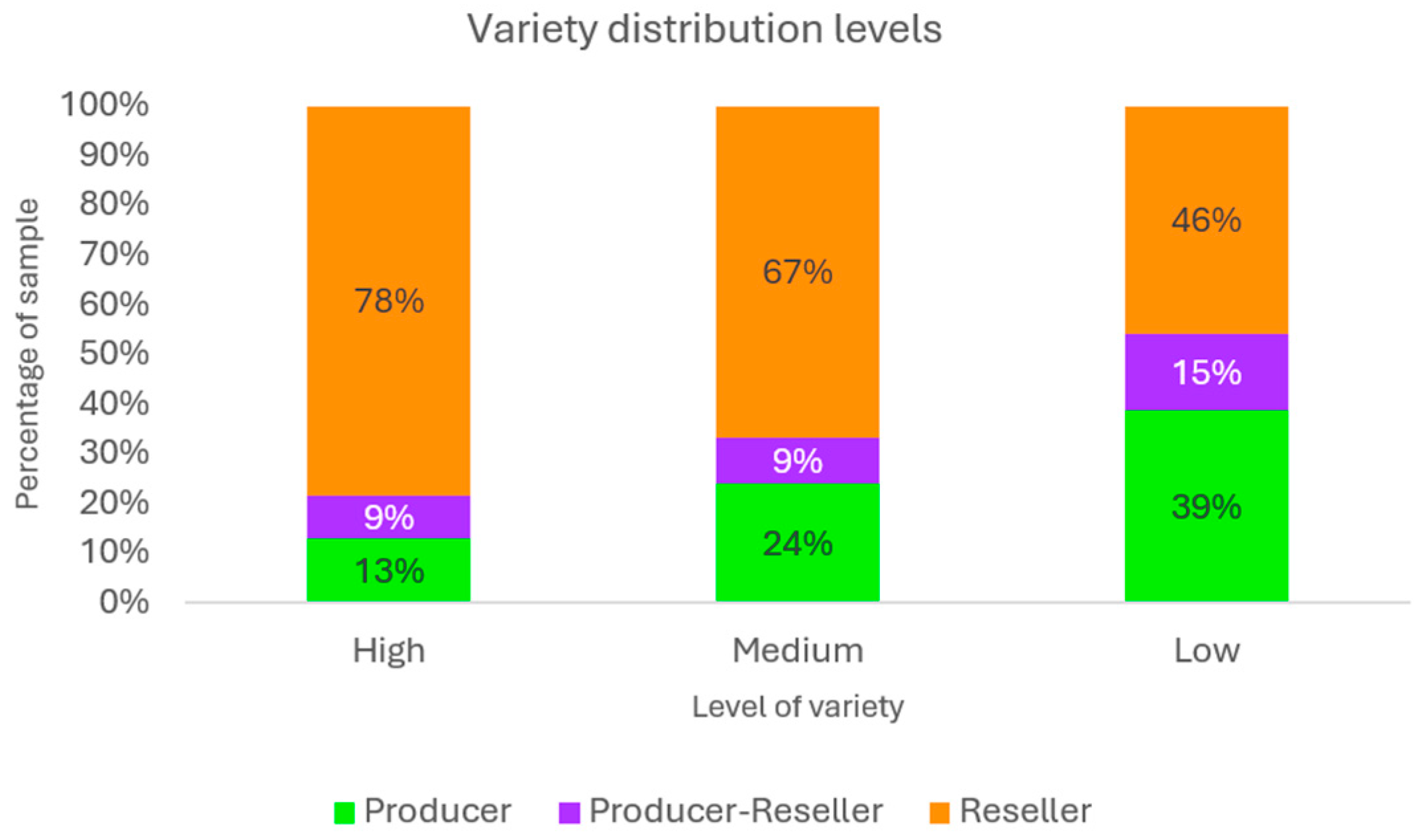

- Variety captures the number of different markets each stallholder attends within a given week, highlighting the geographical scope of their distribution strategy. It is particularly relevant for understanding how vendors circulate products across multiple urban and peri-urban areas, thereby enhancing territorial access to food and reinforcing decentralized supply networks. Variety is categorized as Low (up to three different markets), Medium (four) or High (five or more markets per week). This reflects the multi-scalar relationality emphasized in mobility studies, thus showing how OMMs operate across interconnected urban and peri-urban sites.

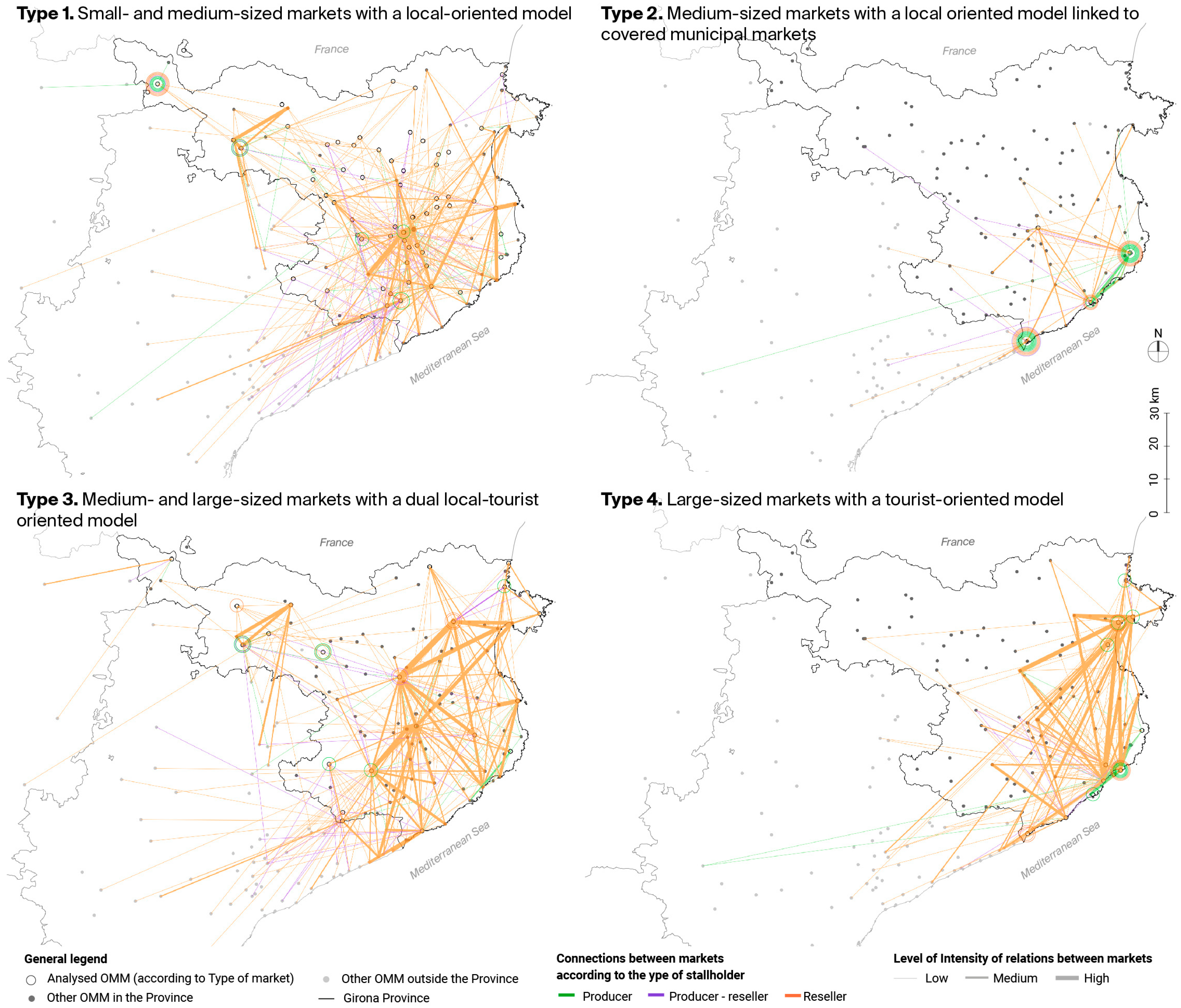

- Closeness measures the degree of spatial proximity between markets, indicating the strength of inter-market connections derived from the stallholders’ mobility patterns. It enables the identification of zones with high concentrations of overlapping vendor activity, where synergies or shared logistics may emerge. Such proximities can be interpreted as opportunities to foster more efficient and cooperative supply infrastructures at the regional level. Three levels of closeness are identified according to the market relations shared between a specific number of vendors: Low (1–3 vendors), Medium (4–6 vendors) and High (7–9 vendors). This indicator also allows a complementary analysis of immobility patterns for stallholders who only work in one single market, thus complementing the rootedness and engagement approach. Such proximities materialize the networked nature of markets to illustrate how vendor flows generate inter-market ties.

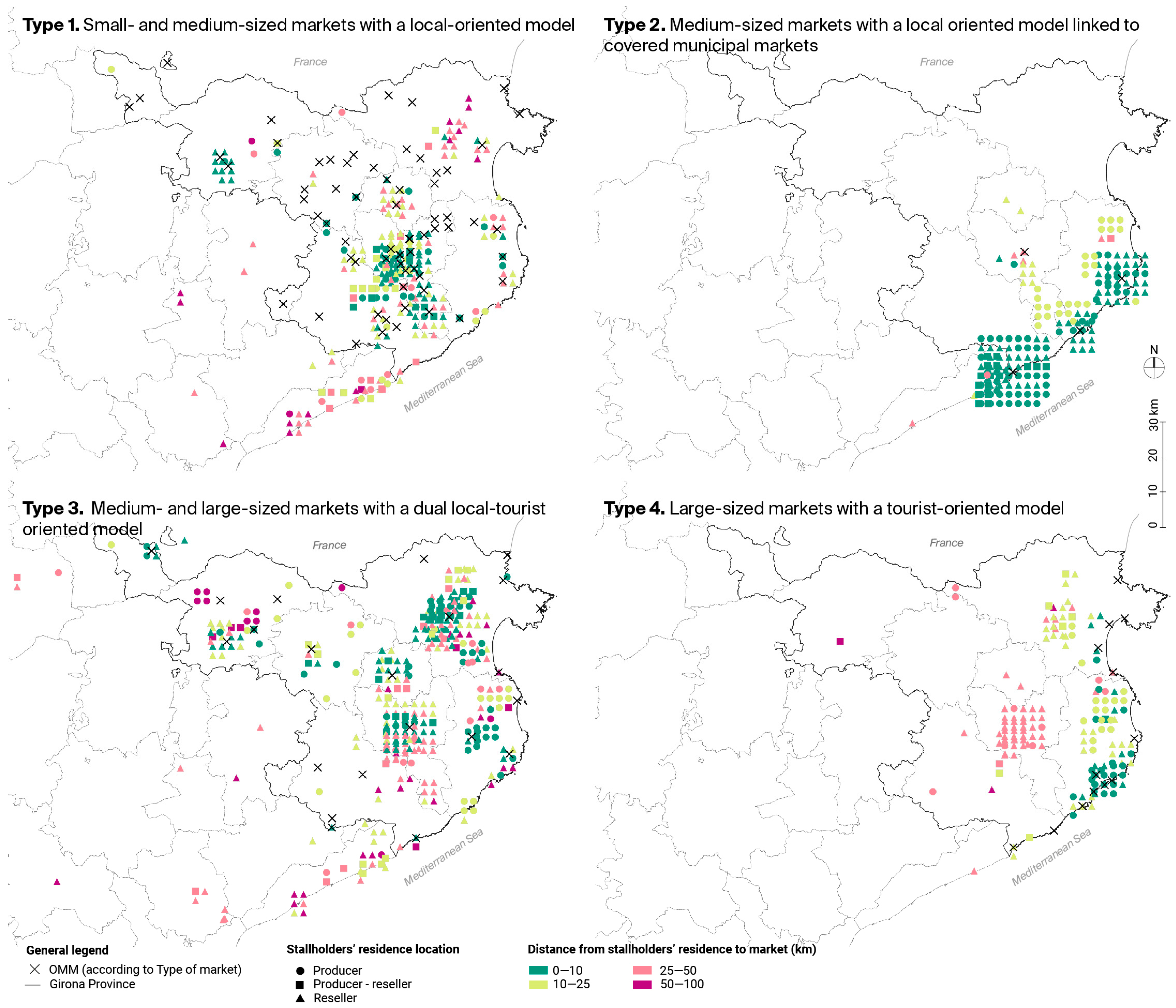

- Rootedness reflects the spatial relationship between stallholders’ places of residence and the markets they attend. This indicator is particularly significant for producers, as it reveals the extent to which markets are anchored in local productive territories and how they may contribute to reinforcing urban–rural linkages and resilience within a sustainable food system framework. Considering 10–20 km radius as the typical range of territorial proximity [45,46], the level of rootedness is categorized as Low (% of vendors from ≤10 km is <30% and mean distance > 25 km), Medium (% of vendors from ≤10 km is between 30 and 60% and/or mean distance between 15 and 25 km) or High (% of vendors from ≤10 km is >60% and mean distance < 15 km). This indicator captures the territorial anchoring stressed in agri-food scholarship and links mobility to place-based resilience [44].

2.4. Phase 3: Data Analysis and Spatial Analysis

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Understanding Vendors’ Mobility Patterns

3.2. Potential Relationships Between Markets

3.3. Urban–Rural Linkages Through Vendor Mobility Patterns

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OMMs | open municipal markets |

| FSC | food supply chain |

| AFNs | alternative food networks |

References

- Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: Exploring their role in rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, J.L.; Komisar, J.D. The integration of food and agriculture into urban planning and design practices. In Sustainable Food Planning: Evolving Theory and Practice; Viljoen, A., Wiskerke, J.S.C., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, Á.; Kovács, S.; Maró, G.; Maró, Z.M. Understanding the relevance of farmers’ markets from 1955 to 2022: A bibliometric review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.E.; Stella, G.; Grohmann, D. Revisiting global food production and consumption patterns by developing resilient food systems for local communities. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Iha, K.; Halle, M.; El Bilali, H.; Grunewald, N.; Eaton, D.; Capone, R.; Debs, P.; Bottalico, F. Mediterranean countries’ food consumption and sourcing patterns: An ecological footprint viewpoint. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 578, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, R.; Bottalico, F.; Ottomano Palmisano, G.; El Bilali, H.; Dernini, S. Food systems sustainability, food security and nutrition in the Mediterranean region: The contribution of the Mediterranean diet. Encycl. Food Secur. Sustain. 2019, 2, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. 2015. Available online: https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Milan-Urban-Food-Policy-Pact-EN.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Moragues-Faus, A. The emergence of city food networks: Rescaling the impact of urban food policies. Food Policy 2021, 103, 102107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipanski, M.E.; MacDonald, G.K.; Rosenzweig, S.; Chappell, M.J.; Bennett, E.M.; Kerr, R.B.; Blesh, J.; Crews, T.; Drinkwater, L.; Lundgren, J.G.; et al. Realizing Resilient Food Systems. BioScience 2016, 66, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Moruzzo, R.; Granai, G. Farmers’ Markets Contribution to the Resilience of the Food Systems. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, N.; Carrasco I Bonet, M.; Garrido I Puig, R. The role of public administrations in promoting open municipal markets. Urban Agric. Region Food Syst. 2022, 7, e20028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Fava, N.; Marciano, C. Consumers’ preferences for local fish products in Catalonia, Calabria and Sicily. In New Metropolitan Perspectives. ISHT 2018. Smart Innovation Systems and Technologies; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Bevilacqua, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 101, pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; González, S.; Waley, P.; Wilkinson, R. Developing Markets as Community Hubs for Inclusive Economies: A Best Practice Handbook for Market Operators; Report; University of Leeds: Leeds, UK, 2022; Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/193068/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Watson, S. The magic of the marketplace: Sociality in a neglected public space. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1577–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: Exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, A.M.; Carsjens, G.J. Markets in municipal code: The case of Michigan cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oñederra-Aramendi, A.; Begiristain-Zubillaga, M.; Malagón-Zaldua, E. Who is feeding embeddedness in farmers’ markets? A cluster study of farmers’ markets in Gipuzkoa. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; González, S. Retail market futures: Retail geographies from and for the margins. In Contemporary Economic Geographies; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S. Contested marketplaces: Retail spaces at the global urban margins. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 877–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, K. Markets, Places, Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy, S.R.; Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Niles, D.; Wiek, A.; Carolan, M.; Kallis, G.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Mangnus, A.; Jehlička, P.; Taherzadeh, O.; et al. Sustainable Agrifood Systems for a Post-Growth World. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteros-Rozas, E.; Ravera, F.; García-Llorente, M. How does agroecology contribute to the transitions towards social-ecological sustainability? Sustainability 2019, 11, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Waley, P. Traditional retail markets: The new gentrification frontier? Antipode 2013, 45, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Geography on the agenda. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2001, 25, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMP; Van Eck, E.; Watson, S.; Van Melik, R.; Breines, M.; Dahinden, J.; Jónsson, G.; Lindmäe, M.; Madella, M.; Menet, J.; et al. Moving marketplaces: Understanding public space from a relational mobility perspective. Cities 2022, 127, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Melik, R.; Spierings, B. Researching public space. From place-based to process-oriented approaches and methods. In Companion to Public Space; Mehta, V., Palazzo, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- González, S. (Ed.) Contested Markets Contested Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M.; Urry, J. The new mobilities paradigm. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Escoda, E.; Moncusí, D. Measuring food supply through closeness and betweenness: Halls and open-air markets in Metropolitan Barcelona. Urban Plan. 2025, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recine, E.; Preiss, P.V.; Valencia, M.; Zanella, M.A. The indispensable territorial dimension of food supply: A view from Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. Development 2021, 64, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Power-Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place. In Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures, Global Change; Bird, J., Curtis, B., Putnam, T., Tickner, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, J.; Jónsson, G.; Menet, J.; Schapendonk, J.; van Eck, E. Placing regimes of mobilities beyond state-centred perspectives and international mobility: The case of marketplaces. Mobilities 2023, 18, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, J. Thinking beyond place: The responsibilities of a relational spatial politics. Geogr. Compass 2009, 3, 1938–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, C. Marchés, Commerçants, Clientèle: Le Commerce Non Sédentaire de la Région Parisienne. Étude de Géographie Humaine. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden, 1983. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, C.; Troin, J.; Chaze, M. Commerce Ambulant et Marchés. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Liège 2016, 66, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Connections. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2004, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku-Boansi, M.; Blija, D.K.; Anin-Yeboah, O.Y.A.; Asibey, M.O.; Amponsah, O. The place of translocal networks in inclusive city development: A systematic review. Urban Gov. 2024, 4, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, C.; Sakdapolrak, P. Translocality: Concepts, applications and emerging research perspectives. Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabinet Ecos. Llibre Blanc dels Mercats No Sedentaris de Catalunya; Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fava, N.; Carrasco Bonet, M.; Roca i Torrent, A. Informe Els Mercats No Sedentaris a la Província de Girona: Una Oportunitat per la Transició Alimentària? Universitat de Girona. 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10256/24177 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Morales, A. Public markets as community development tools. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2009, 28, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazo-Moratalla, A.; Troncoso-González, I.; Moreira-Muñoz, A. Regenerative food systems to restore urban–rural relationships: Insights from the Concepción metropolitan area foodshed (Chile). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raton, G.; Raimbert, C. Livrer en circuits courts: Les mobilités des agriculteurs comme révélateur des territoires alimentaires émergents. Étude de cas dans les Hauts-de-France. Géocarrefour 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Alternative (shorter) food supply chains and specialist livestock producers in the Scottish–English borders. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 823–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Schermer, M.; Rossi, A. Building food democracy: Exploring civic food networks and newly emerging forms of food citizenship. Int. J. Socio. Agric. Food 2012, 19, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Rastoin, J.-L. Les systèmes alimentaires territorialisés: Le cadre conceptuel. J. Resolis 2015, 4, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, D.; Mastronardi, L.; Giannelli, A.; Giaccio, V.; Mazzocchi, G. Territorialisation dynamics for Italian farms adhering to alternative food networks. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Series 2018, 40, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, M.; Heffernan, W. Opening spaces through relocalization: Locating potential resistance in the weaknesses of the global food system. Sociol. Rural. 2002, 42, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A. Le marché de plein vent alimentaire, un lieu en marge du commerce de détail alimentaire français? Géocarrefour 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A. On farmers markets as wicked opportunities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.; Hope, C. Ecological connections: Reimagining the role of farmers’ markets. Rural Soc. 2014, 23, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenfelt, Å.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Farmers’ markets: Linking food consumption and the ecology of food production? Local Environ. 2010, 15, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, E.; Schapendonk, J. Moving Behind the Scenes of Public Space: The Differentiation of Market Traders’ Routinized Mobilities. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2024, 26, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R. Food system transformation: Urban perspectives. Cities 2023, 134, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, L.; Van den Broeck, G. Local food systems: Reviewing two decades of research. Agric. Syst. 2021, 193, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.C. Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. J. Rural. Stud. 2000, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; Marsden, T. Beyond the divide: Rethinking relationships between alternative and conventional food networks in Europe. J. Econ. Geogr. 2006, 6, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Society 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittman, H.; Desmarais, A.A.; Wiebe, N. (Eds.) Food Sovereignty: Reconnecting Food, Nature and Community; Fernwood Publishing: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Morley, A. Sustainable Food Systems: Building a New Paradigm; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P.; de Labarre, M.D.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Maj, A.; Majewski, E.; et al. Short Food Supply Chains and Their Contributions to Sustainability: Participants’ Views and Perceptions from 12 European Cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.; Rendall, S.; Reitsma, F. Resilience food systems: A qualitative tool for measuring food resilience. Urban Ecosyst. 2016, 19, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; Marsden, T.; Moragues-Faus, A. Relationalities and convergences in food security narratives: Towards a place-based approach. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2016, 41, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Distance Variables | Intensity Levels | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type M | NM | NC | Min | Max | Mean | Median | Std.D | CV | Low | Med | High |

| 1 | 67 | 447 | 0.18 | 115.61 | 28.63 | 25.42 | 18.62 | 0.65 | 97% (435) | 2.8% (11) | 0.2% (1) |

| 2 | 4 | 78 | 0.19 | 133.91 | 25.03 | 21.80 | 21.40 | 0.85 | 99% (77) | 1% (1) | 0% (0) |

| 3 | 21 | 364 | 0.18 | 89.14 | 29.64 | 26.17 | 18.80 | 0.63 | 94.5% (344) | 5% (18) | 0.5% (2) |

| 4 | 13 | 219 | 0.00 | 124.00 | 30.81 | 28.00 | 22.75 | 0.74 | 92.7% (203) | 7.3% (16) | 0% (0) |

| Type_M | ≤10 km | 10–25 km | 25–50 km | >50 km | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N_V | % | N_V | % | N_V | % | N_V | % | N_V | Mean (km) | Level of Rootedness | |

| 1 | 92 | 35% | 81 | 31% | 66 | 25% | 21 | 8% | 260 | 19.25 | Medium |

| 2 | 146 | 77% | 35 | 19% | 7 | 4% | 1 | 1% | 189 | 5.34 | High |

| 3 | 127 | 36% | 90 | 25% | 93 | 26% | 47 | 13% | 357 | 23.53 | Medium |

| 4 | 35 | 20% | 54 | 31% | 58 | 33% | 29 | 16% | 176 | 20.36 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carrasco-Bonet, M.; Fava, N.; González, S. Open Municipal Markets as Networked Ecosystems for Resilient Food Systems. Sustainability 2026, 18, 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010328

Carrasco-Bonet M, Fava N, González S. Open Municipal Markets as Networked Ecosystems for Resilient Food Systems. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010328

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrasco-Bonet, Marta, Nadia Fava, and Sara González. 2026. "Open Municipal Markets as Networked Ecosystems for Resilient Food Systems" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010328

APA StyleCarrasco-Bonet, M., Fava, N., & González, S. (2026). Open Municipal Markets as Networked Ecosystems for Resilient Food Systems. Sustainability, 18(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010328