Applications and Uses of Moringa Oleifera Seeds for Water Treatment, Agricultural Fertilization, and Nutraceuticals

Abstract

1. Introduction

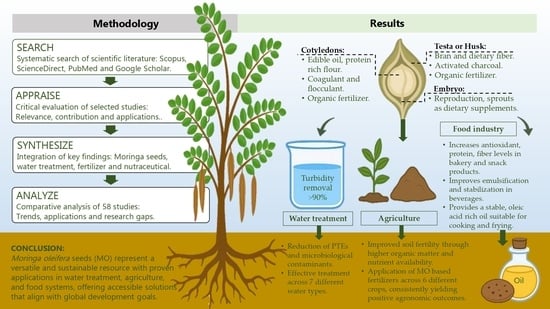

2. Methodology

3. Applications and Uses of Moringa oleifera Seeds for Water Treatment

4. Applications and Uses of M. oleifera Seeds for Agricultural Fertilization

5. Applications and Uses of Moringa Oleifera Seeds as a Nutraceutical in the Food Industry

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bania, J.K.; Deka, J.R.; Hazarika, A.; Das, A.K.; Nath, A.J.; Sileshi, G.W. Modelling habitat suitability for Moringa oleifera and Moringa stenopetala under current and future climate change scenarios. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oduro, I.; Ellis, W.O.; Owusu, D. Nutritional potential of two leafy vegetables: Moringa oleifera and Ipomoea batatas leaves. Sci. Res. Essays 2008, 3, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- El Bilali, H.; Guimbo, I.D.; Nanema, R.K.; Falalou, H.; Kiebre, Z.; Rokka, V.-M.; Tietiambou, S.R.F.; Nanema, J.; Dambo, L.; Grazioli, F.; et al. Research on Moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) in Africa. Plants 2024, 13, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, D.; Babu, N.K. Moringa oleifera: A review on nutritive significance and its medicinal application for children. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2024, 12, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; Spada, A.; Battezzati, A.; Schiraldi, A.; Aristil, J.; Bertoli, S. Moringa oleifera Seeds and Oil: Characteristics and Uses for Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, A.; Duarte, C.M.; Sousa, I. Moringa oleifera Seeds Characterization and Potential Uses as Food. Foods 2022, 11, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzuvor, C.K.O.; Pan, S.; Amanze, C.; Amuzu, P.; Asakiya, C.; Kubi, F. Bioactive components from Moringa oleifera seeds: Production, functionalities and applications—A critical review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 42, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Martyn-St James, M.; Clowes, M.; Sutton, A. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, N.U.; Cusioli, L.F.; Quesada, H.B.; Ferreira, M.E.C.; Fagundes-Klen, M.R.; Vieira, A.M.S.; Gomes, R.G.; Vieira, M.F.; Bergamasco, R. A review of Moringa oleifera seeds in water treatment: Trends and future challenges. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 147, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chales, G.G.; Tihameri, B.S.; Milhan, N.V.M.; Koga-Ito, C.Y.; Antunes, M.L.P.; dos Reis, A.G. Impact of Moringa oleifera Seed-Derived Coagulants Processing Steps on Physicochemical, Residual Organic, and Cytotoxicity Properties of Treated Water. Water 2022, 14, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jadabi, N.; Laaouan, M.; El Hajjaji, S.; Mabrouki, J.; Benbouzid, M.; Dhiba, D. The Dual Performance of Moringa Oleifera Seeds as Eco-Friendly Natural Coagulant and as an Antimicrobial for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo-Portillo, J.J.; Ponce-González, A.; González-Coronel, V.J.; Vega-Sánchez, M.; Zayas-Pérez, M.T.; Soriano-Moro, G. Utilización de Moringa oleífera como un coagulante-floculante natural para la descontaminación de agua. RD-ICUAP 2024, 10, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Manning, G.; Zakharova, J.; Arjunan, A.; Batool, M.; Hawkins, A.J. Particle size effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. seeds on the turbidity removal and antibacterial activity for drinking water treatment. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 6, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Pilco, G.; Estrada Cárdenas, F. Efecto de la semilla de la Moringa oleífera en polvo como coagulante natural para la remoción de la turbidez del agua del río Caplina, Perú. Rev. Soc. Quím. Perú 2024, 90, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhut, H.T.; Hung, N.T.Q.; Lap, B.Q.; Han, L.T.N.; Tri, T.Q.; Bang, N.H.K.; Hiep, N.T.; Ky, N.M. Use of Moringa oleifera seeds powder as bio-coagulants for the surface water treatment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 18, 2173–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Cabrera, G.A.; Alvarez-Arteaga, G.; Orozco-Hernández, M.E.; Reyes-Zuazo, M.A. Tratamiento primario de aguas almacenadas en estanques rústicos mediante la aplicación de coagulantes químicos y biológicos. Ecosist. Recur. Agropec. 2021, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Guzmán, C.; Ortiz-Gutierrez, B.E. Evaluation of Three Natural Coagulant from Moringa Oleifera Seed for the Treatment of Synthetic Greywater. Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 8, 3842–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agunwamba, J.C.; Amu, A.M.; Nwonu, D.C. An efficient biosorbent for the removal of arsenic from a typical urban-generated wastewater. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.C.G.; Ovallos, C.A.M.; Agudelo-Castañeda, D.M.; Paternina-Arboleda, C.D. Exploring Moringa oleifera: Green Solutions for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment and Agricultural Advancement. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.C.; Al Matar, M.; Makky, E.A.; Ali, E.N. The use of Moringa oleifera seed as a natural coagulant for wastewater treatment and heavy metals removal. Appl. Water Sci. 2016, 7, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos, A.G.Z.; Gutiérrez, J.; Caballero, P. Use of Moringa Oleifera as a Natural Coagulant in the Reduction of Water Turbidity in Mining Activities. Water 2024, 16, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, W.M.; Bote, M.E. Wastewater treatment using a natural coagulant (Moringa oleifera seeds): Optimization through response surface methodology. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Ismail, N.; Chua, B.L.; Adnan, A.S.M. Drying and extraction of Moringa oleifera and its application in wastewater treatment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2120, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadadi, A.; Imessaoudene, A.; Bollinger, J.-C.; Cheikh, S.; Assadi, A.A.; Amrane, A.; Kebir, M.; Mouni, L. Parametrical Study for the Effective Removal of Mordant Black 11 from Synthetic Solutions: Moringa oleifera Seeds’ Extracts Versus Alum. Water 2022, 14, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehwish, H.M.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Xiong, Y.; Cai, H.; Aadil, R.M.; Mahmood, Q.; He, Z.; Zhu, Q. Green synthesis of a silver nanoparticle using Moringa oleifera seed and its applications for antimicrobial and sun-light mediated photocatalytic water detoxification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D.; Lovera, D.; Villaca, J. Tratamiento de aguas residuales de un centro de beneficio avícola usando Moringa oleifera. Rev. Inst. Investig. Fac. Minas Metal. Cienc. Geogr. 2023, 26, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wagh, M.P.; Aher, Y.; Mandalik, A. Potential of Moringa oleifera seed as a natural adsorbent for wastewater treatment. Trends Sci. 2022, 19, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Yusuf, F.H.B.C.; Derek, C. Optimization of Moringa oleifera seed extract and chitosan as natural coagulant in treatment of fish farm wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 256, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofgea, N.M.; Tura, A.M.; Fanta, G.M. Activated carbon from H3PO4-activated Moringa stenopetale Seed Husk for removal of methylene blue: Optimization using the response surface method (RSM). Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2022, 16, 100214. [Google Scholar]

- Donyanavard, P.; Tavakoli, A.; Rout, P.R.; Yuan, Q. Valorization of agricultural by-product Moringa stenopetala seed husks into activated carbon for Reactive Black and Basic Blue dye removal from textile wastewater. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 15, 24259–24277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sera, P.R.; Diagboya, P.N.; Akpotu, S.O.; Mtunzi, F.M.; Chokwe, T.B. Potential of valourized Moringa oleifera seed waste modified with activated carbon for toxic metals decontamination in conventional water treatment. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 16, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.F.; Oluyamo, S.S.; Fuwape, I.A. Synthetic Characterization of Cellulose from Moringa oleifera seeds and Potential Application in Water Purification. J. Niger. Soc. Phys. Sci. 2021, 3, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, M.H.M.; Ngadi, N. Ecotoxicological risk assessment on coagulation-flocculation in water/wastewater treatment: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 52631–52657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, T.S.; El-Hadidy, G.A.E.-M.; Shaaban, F.K.M.; Hemdan, N.A. Effect of organic fertilization with Moringa oleifera seeds cake and compost on storability of Valencia orange fruits. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 65, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemdan, N.A.; Mahmoud, T.S.M.; Abdalla, A.M.; Man-Sour, H.A. Using Moringa oleifera seed cake and compost as organic soil amendments for sustainable agriculture in Valencia orange orchard. Food Agric. Soc. 2021, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.S.; Saleh, S.A.; Sulman, A. An attempt to use Moringa products as a natural nutrients source for Lettuce organically production. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohim, F.M.; Mahmoud, T.S.M.; Tong, Y.; Saleh, S.A. Influence of Moringa Seed Cake and Vermicompost on Soil Microbial Activity, Growth, and Productivity of ‘Anna’ Apple Trees. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2023, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ban, C.; Zhao, T.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, N.; Ma, L.; Zhou, J.; Deng, X. Harnessing moringa seed extract for control of soil nitrate accumulation and nitrous oxide emissions on the Loess Plateau. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 206, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.M.; Mohamed, A.S.; Mazhar, A.A.-H.; Thabet, R.S. Effect of Moringa oleifera Seed Cake as an Eco-friendly Fertilization Source on the Performance of Snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus L.) Plant Grown in Sandy Soil. Egypt. J. Hortic. 2024, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, S.A.; Zaku, S.G.; Adedirin, S.O.; Tafida, M.; Thomas, S.A. Moringa oleifera seed-cake, alternative biodegradable and biocompatibility organic fertilizer for modern farming. Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 2011, 2, 1289–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosshagauer, S.; Pirkwieser, P.; Kraemer, K.; Somoza, V. The Future of Moringa Foods: A Food Chemistry Perspective. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 751076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehwish, H.M.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Xiong, Y.; Zheng, K.; Xiao, H.; Anjin, T.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; He, Z. Moringa oleifera—A Functional Food and Its Potential Immunomodulatory Effects. Food Rev. Int. 2020, 38, 1533–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milla, P.G.; Peñalver, R.; Nieto, G. Health Benefits of Uses and Applications of Moringa oleifera in Bakery Products. Plants 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, J.; Kumar, K.A.; Indrani, D.; Radha, C. Effect of Moringa oleifera seed flour on the rheological, physico-sensory, protein digestibility and fatty acid profile of cookies. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 4731–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Abascal, V.; Duarte-Ginorio, M.; Martínez-Azcarraga, M.; Almora-Hernández, E.; Figueredo-Moreno, N.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, E. Caracterización y uso de la cáscara de semillas de Moringa oleífera como salvado en la fortificación de mini panqués. Centro Azúcar. 2022, 49, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Selvasekaran, P.; Kapoor, S.; Barbhai, M.D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Saurabh, V.; Potkule, J.; Changan, S.; ElKelish, A.; Selim, S.; et al. Moringa oleifera Lam. seed proteins: Extraction, preparation of protein hydrolysates, bioactivities, functional food properties, and industrial application. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 131, 107791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, C.; Castelló, M.L.; Ortolá, M.D. Potentiality of Moringa oleifera as a nutritive ingredient in different food matrices. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2023, 78, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Peng, S.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; et al. Fabrication and stability of Pickering emulsions using moringa seed residue protein: Effect of pH and ionic strength. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3484–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liao, L.; McClements, D.J.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Zou, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, W. Utilizing protein-polyphenol molecular interactions to prepare moringa seed residue protein/tannic acid Pickering stabilizers. LWT 2022, 154, 112814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Wu, X. Optimization of Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Moringa oleifera Seed Oil Using Response Surface Methodological Approach and Its Antioxidant Activity. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Naeem, H.; Batool, M.; Imran, M.; Hussain, M.; Mujtaba, A.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Ghoneim, M.M.; et al. Antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory potential of Moringa seed and Moringa seed oil: A comprehensive approach. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 6157–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Abascal, V.; León-Sánchez, G.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, E. Evaluación de la actividad biológica del aceite de semillas de Moringa oleífera. Rev. Cuba. Plantas Med. 2023, 27, e1382. [Google Scholar]

- Iranloye, Y.M.; Omololu, F.O.; Olaniran, A.F.; Abioye, V.F. Assessment of potentials of Moringa oleifera seed oil in enhancing the frying quality of soybean oil. Open Agric. 2021, 6, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkarim, S.; Long, K.; Lai, O.; Muhammad, S.; Ghazali, H. Frying quality and stability of high-oleic Moringa oleifera seed oil in comparison with other vegetable oils. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukandoul, S.; Zaidi, F.; Santos, C.S.P.; Casal, S. Moringa oleifera Oil Nutritional and Safety Impact on Deep-Fried Potatoes. Foods 2023, 12, 4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Gastélum, J.A.; Arguijo-Sustaita, A.A.; López-Díaz, J.A.; Díaz-Sánchez, Á.G.; Hernández-Peña, C.C.; Cota-Ruiz, K. Seed germination and sprouts production of Moringa oleifera: A potential functional food? J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2023, 22, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodas, F.; Zorzenon, M.R.T.; Milani, P.G. Moringa oleifera potential as a functional food and a natural food additive: A biochemical approach. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2021, 93, e20210571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saa, R.W.; Fombang, E.N.; Ndjantou, E.B.; Njintang, N.Y. Treatments and uses of Moringa oleifera seeds in human nutrition: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1911–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Serrano, C.M.; Zumalacárregui-de-Cárdenas, B.; Mazorra-Mestre, M. Potencialidad de la semilla de moringa como ingrediente alimenticio beneficioso para la salud. Rev. Cuba. Quím. 2024, 36, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Treated Water | Seed Form | Main Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface and Drinking Waters | Synthetic (kaolin-based turbid water) | Sun-dried and milled seeds (0.25–0.8 mm) | Turbidity reduced from 80 NTU to 5 NTU; total E. coli removal; met WHO standards. | |

| Surface water (Río Caplina, Peru) | Manually powdered seeds | Turbidity removal up to 97%; met Peruvian potable water standards. | ||

| Surface water from Vietnam | Powdered seeds | Turbidity reduction between 88 and 95% under optimal conditions. | ||

| Pond-stored water | Aqueous extract alone and mixed with alum (70/30 w/w) | Over 95% turbidity removal in 60 min (mix); 90% with extract alone in 180 min. | ||

| Domestic and Municipal Wastewaters | Synthetic graywater | Seed husk, ground seed, and defatted seed extracts | Defatted extract: 85% removal; husk: 75%; pH and DO affect by coagulant type. | |

| Municipal wastewater (Colombia) | Powdered seeds and aqueous extract | Turbidity 85–95%; COD and TSS reduction; residues reused as soil amendment. | ||

| Waste water | Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) | Arsenic | Defatted powdered seeds (biosorbent) | As(V) removal up to 99% at pH 4; pseudo-second-order kinetics; Langmuir isotherm. |

| Malaysian industrial effluent | Seed cake (1% w/v) | Fe 99%, Cu & Cd 98%, Pb 78%; minimal pH/TDS changes. | ||

| Ecuadorian mining effluent | Seed paste | >90% turbidity reduction; comparable to alum without chemical sludge formation. | ||

| As, Cd, Pb | Defatted seed waste modified with activated carbon | >90% removal; reusable and stable adsorbent. | ||

| Dye wastewater | Congo Red | Air-dried and saline seed extract | 94% turbidity and 70% COD removal. | |

| Mordant Black 11 | Aqueous and saline seed extracts | 80% aqueous and 95% saline removal. | ||

| Methylene blue | Seed extract (reductant and stabilizer) and AgNPs | 96% methylene blue removal; strong antibacterial activity. | ||

| Industrial dye water | Activated carbon from seed husks | 99.4% methylene blue removal; adsorption capacity 436.7 mg/g. | ||

| Textile industry dyes | Activated carbon from seed husks | High color removal; surface area and oxygenated functional groups. | ||

| Agro industrial effluents | Poultry wastewater | Aqueous seed extract | Reduction in turbidity, BOD5, COD, TSS, coliforms, oils, and fats. | |

| Synthetic dairy wastewater | Powdered seed | 95% turbidity and 94% color removal. | ||

| Fish-farm wastewater | Seed extract and chitosan | Moringa: 47% turbidity; chitosan: 84%; confirms biodegradability. | ||

| Crop System | Methodology | Main Results | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valencia orange (Citrus sinensis) | Application of MO seed cake + compost compared to conventional fertilization. | Improved fruit quality and extended postharvest shelf life. | Enhances fruit preservation and physiological quality. |

| Application of moringa seed cake alone and combined with compost. | Enhanced organic carbon, nitrogen, and cation exchange capacity; improved nutrient uptake and fruit productivity. | Promotes long-term soil fertility. | |

| Lettuce (‘Balady’ variety) | Comparison among moringa seed cake, vermicompost, ammonium sulfate, and foliar leaf extract (5–10 g/L). | Increased plant growth, chlorophyll, and nutrient content; reduced nitrate accumulation. | Boosts yield quality while lowering nitrate levels and supporting organic farming. |

| ‘Anna’ apple orchard (Malus domestica) | Combined application of moringa seed cake and vermicompost vs. farmyard manure. | Higher microbial activity, improved soil fertility, and better fruit yield and quality. | Acts as both nutrient source and soil biostimulant. |

| Ornamental plant (Antirrhinum majus) | Greenhouse trial (2020–2022) using moringa seed cake (15–30 g) + microbial biostimulant. | Enhanced vegetative and floral development, pigment and nutrient content. | Effective biofertilizer for low-fertility ornamental crops. |

| Maize (Zea mays) | Application of hexane-extracted and aqueous moringa seed cake. | Increased soil minerals (K, Mg, Ca, P, N), microbial activity, and yield (1 to 5 kg). | Eco-friendly, low-cost alternative to chemical fertilizers. |

| Loess Plateau agricultural soils | Application of moringa seed extract as a biostimulant. | Reduced nitrate accumulation and N2O emissions; improved nitrogen efficiency. | Mitigates nitrogen pollution and supports climate-smart soil management. |

| Municipal and industrial wastewater sludge reuse | Reuse of moringa sludge from coagulation treatment as a soil amendment. | Improved organic matter, N, P, K, and microbial activity in soils. | Supports circular bioeconomy through waste valorization. |

| Application Area | Functional Ingredients | Functional Properties | Food Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General composition | High-quality proteins, oleic acid, minerals (Ca, K, Mg, Fe), bioactive compounds (isothiocyanates, phenolics, tocopherols, sterols). | Antioxidant, hypocholesterolemic, antihyperglycemic, immunomodulatory. | Ingredient for functional and nutraceutical formulations. | Complete amino acid profile; similar to high-value legumes. |

| Bakery products | Seed flour and extracts, husk powder | Increase protein, fiber, and antioxidant content; improve digestibility. | Fortified breads, cookies, muffins | Moderate inclusion levels maintain texture, color, and acceptability. |

| Functional beverages and dairy | Protein isolates, hydrolysates, Pickering emulsions. | High solubility, emulsifying and foaming capacity; antioxidant activity. | Functional drinks, fortified dairy beverages | Stable emulsions; improved antioxidant properties with tannic acid. |

| Edible oil | Oleic acid (>70%), tocopherols, phenolics. | Oxidative stability, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential. | Culinary oil, frying, dressings | CO2 extraction preserves bioactives, yields low trans fats |

| Germinated seeds | Proteins, lipids, glucosinolates, phenolics. | Enhanced antioxidant capacity and nutrient bioavailability. | Fortified foods, dietary supplements | Germination reduces antinutrients and improves functionality. |

| Processing and safety | Fermentation, soaking, roasting, aqueous extraction. | Reduces phytates, tannins, saponins, lectins, trypsin inhibitors. | Pre-treatment in food formulations | Thermal processing deactivates glucosinolates. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moreno, D.J.; Romero, C.C.; Lovera, D.F. Applications and Uses of Moringa Oleifera Seeds for Water Treatment, Agricultural Fertilization, and Nutraceuticals. Sustainability 2026, 18, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010003

Moreno DJ, Romero CC, Lovera DF. Applications and Uses of Moringa Oleifera Seeds for Water Treatment, Agricultural Fertilization, and Nutraceuticals. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno, Diana J., Consuelo C. Romero, and Daniel F. Lovera. 2026. "Applications and Uses of Moringa Oleifera Seeds for Water Treatment, Agricultural Fertilization, and Nutraceuticals" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010003

APA StyleMoreno, D. J., Romero, C. C., & Lovera, D. F. (2026). Applications and Uses of Moringa Oleifera Seeds for Water Treatment, Agricultural Fertilization, and Nutraceuticals. Sustainability, 18(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010003