Co-Planning of Electrolytic Aluminum Industrial Parks with Renewables, Waste Heat Recovery, and Wind Power Subscription

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- It establishes an optimal planning framework for EA-based industrial parks, jointly determining the capacities of self-owned PV/wind generation, external wind subscription contracts, and adjustable heat exchangers.

- (2)

- It explicitly models EA electro-thermal coupling and temperature safety constraints while incorporating waste heat recovery pathways and combined cooling–heating–power (CCHP) supply, thereby enabling EA-process heat to be valorized for nearby thermal users.

- (3)

- It incorporates wind power priority subscription and green certificate compliance requirements, thereby aligning enterprise-level planning with renewable integration and “green electricity aluminum” production targets.

- (4)

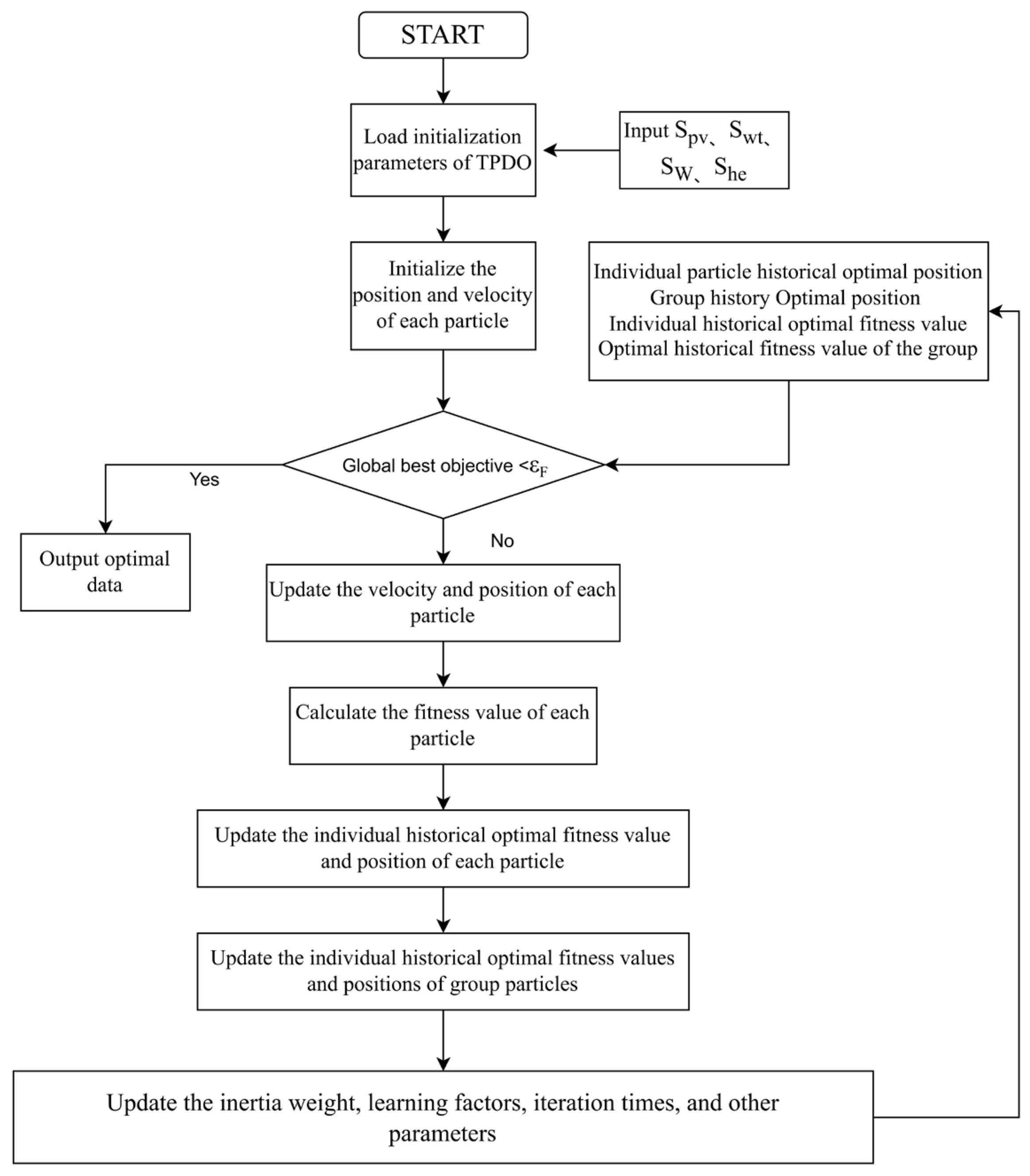

- It develops a two-stage PSO–deterministic optimization (TPDO) scheme. At the upper stage, a particle swarm metaheuristic explores investment decisions; at the lower stage, a deterministic dispatch model solves hourly operations with EA thermal constraints. This approach ensures tractable solutions for a nonconvex mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem.

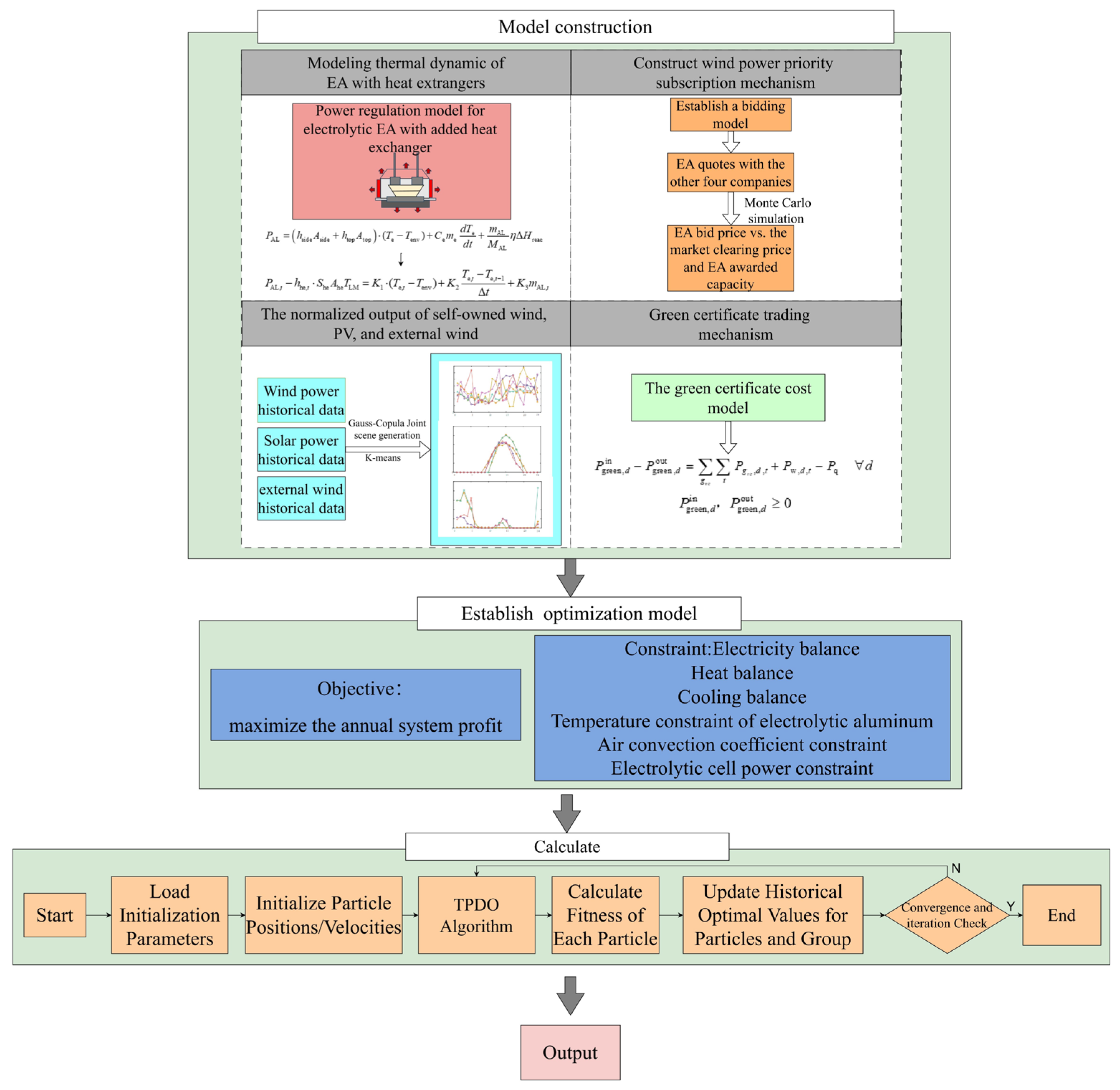

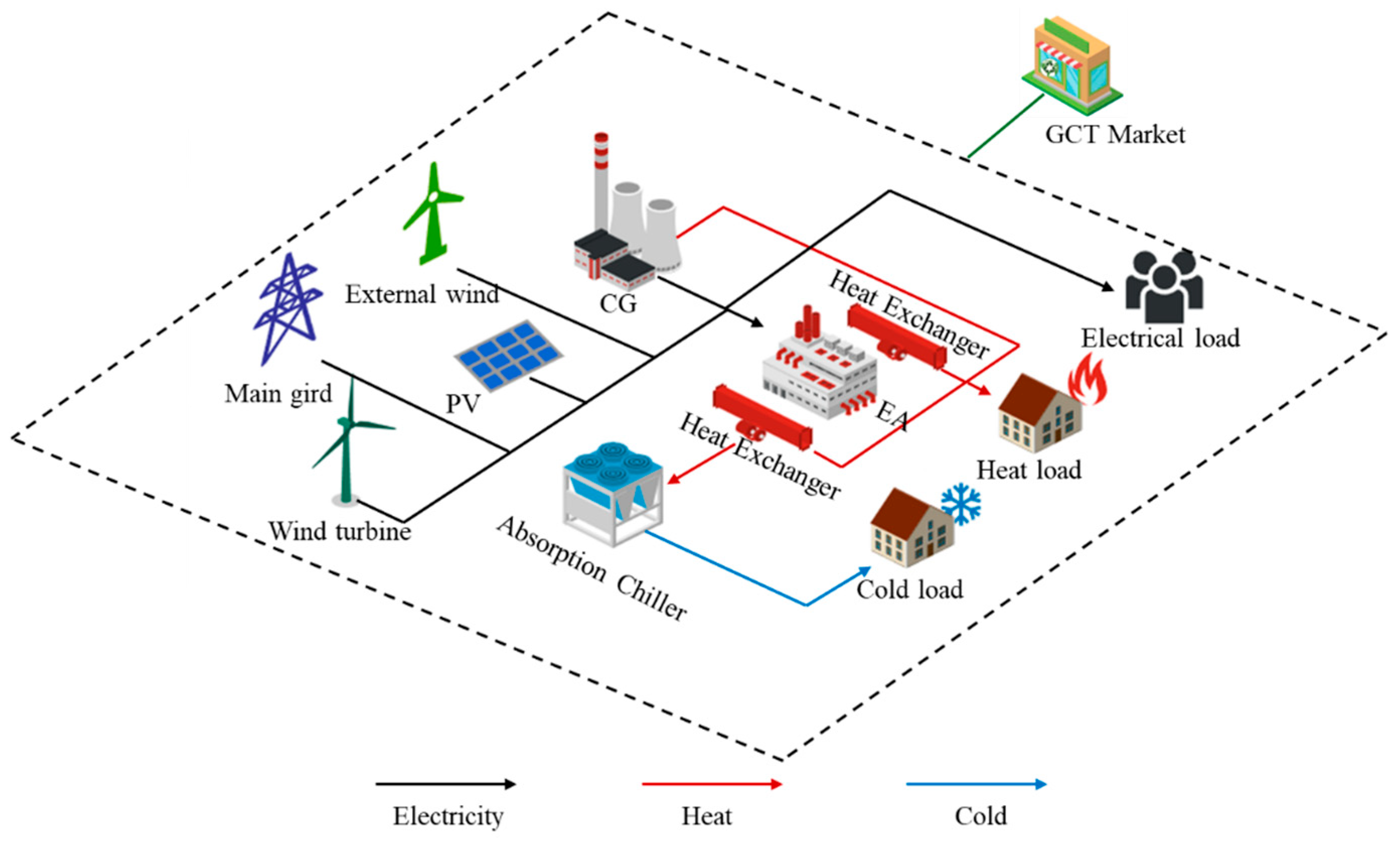

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Modeling the Thermal Dynamics of EA with Heat Exchangers

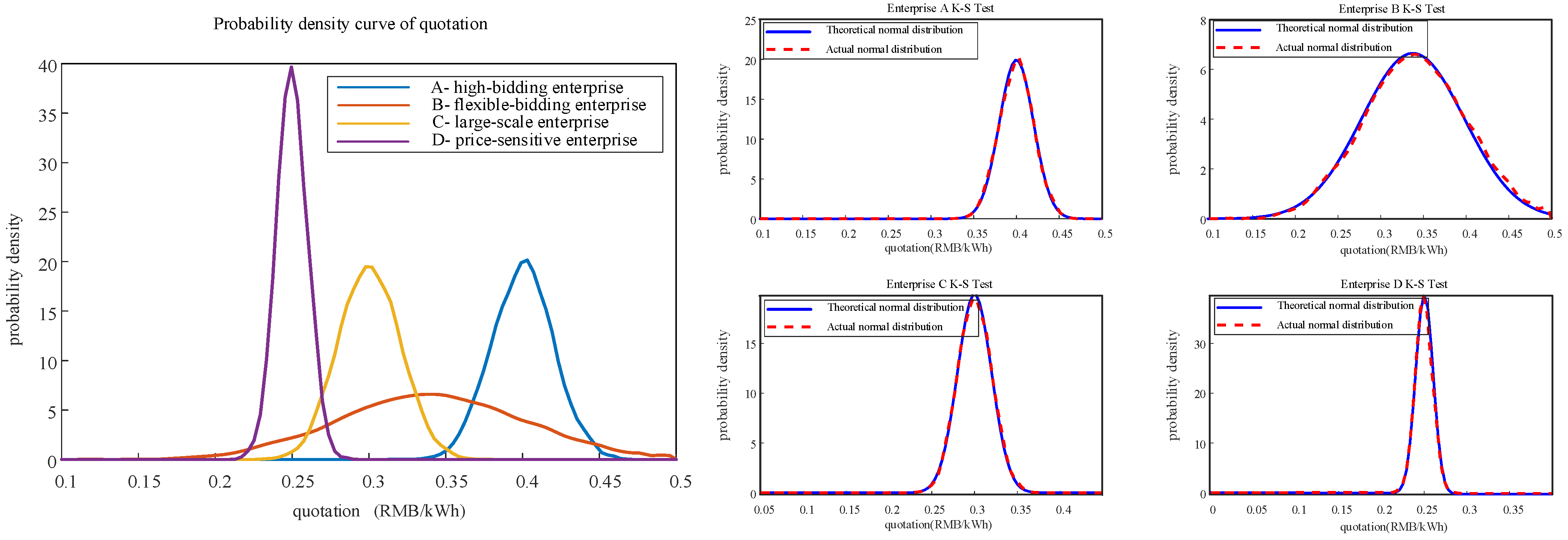

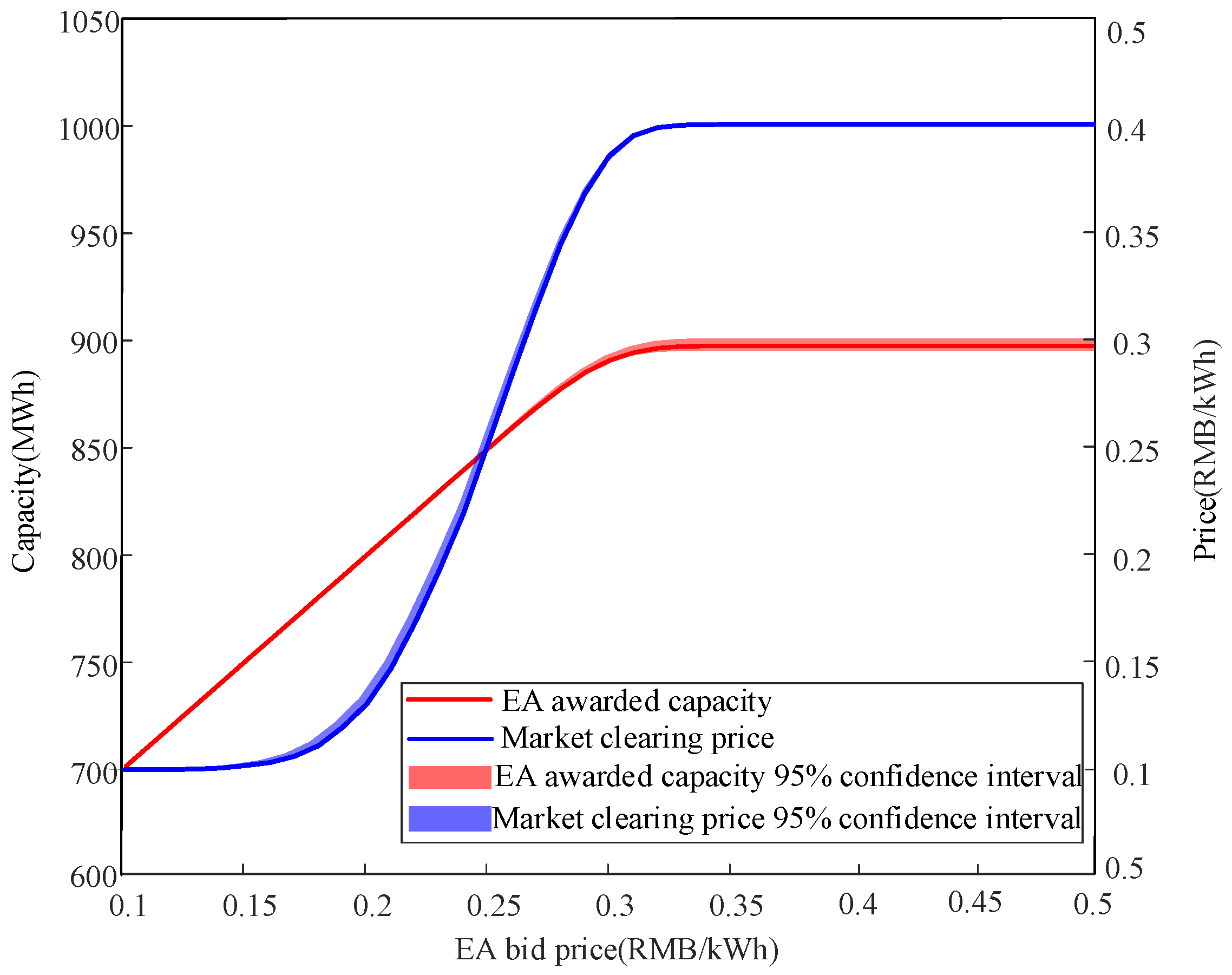

4. Regional Curtailed Wind Capacity Subscription Mechanism

5. Optimal Plan Framework of an EA Industrial Park

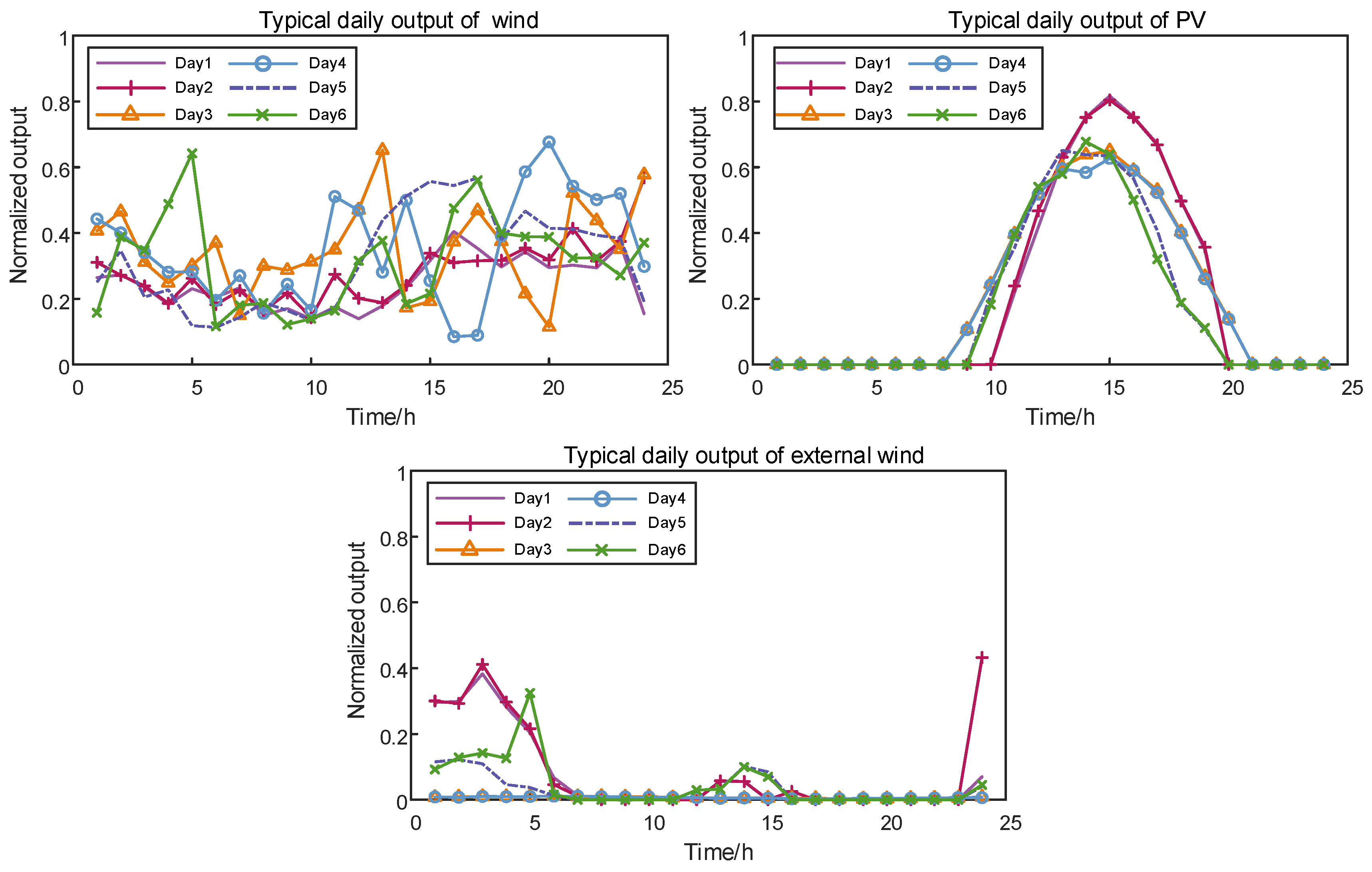

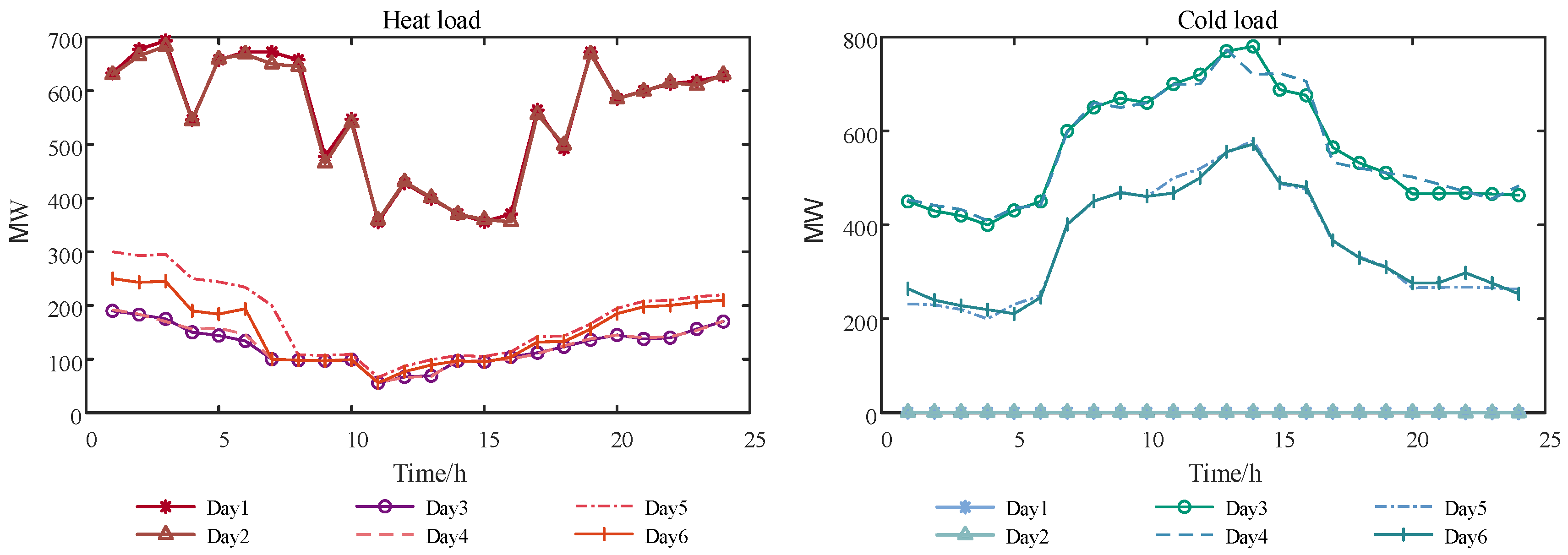

5.1. Time Resolution

5.2. Objective Function

5.3. Green Certificate Trading Mechanism

5.4. Energy Balances

5.5. DER Models

6. Two-Stage PSO–Deterministic Optimization (TPDO) Algorithm

7. Case Study

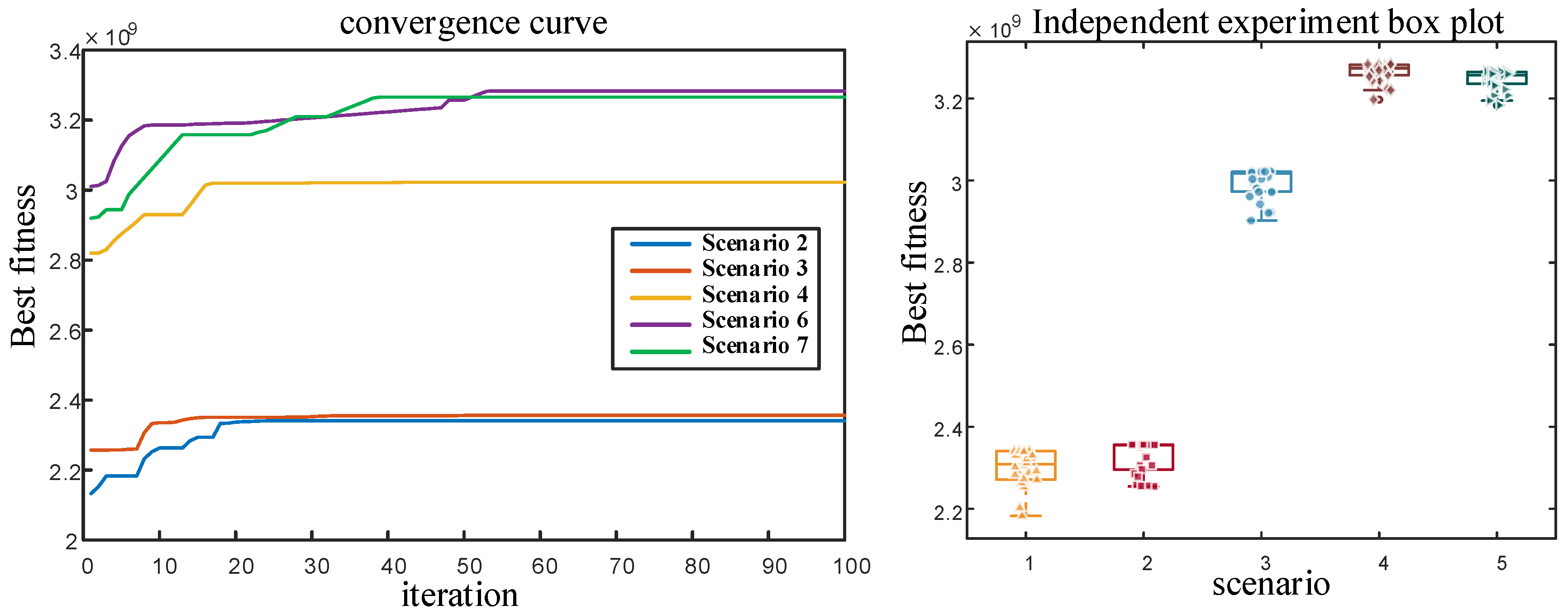

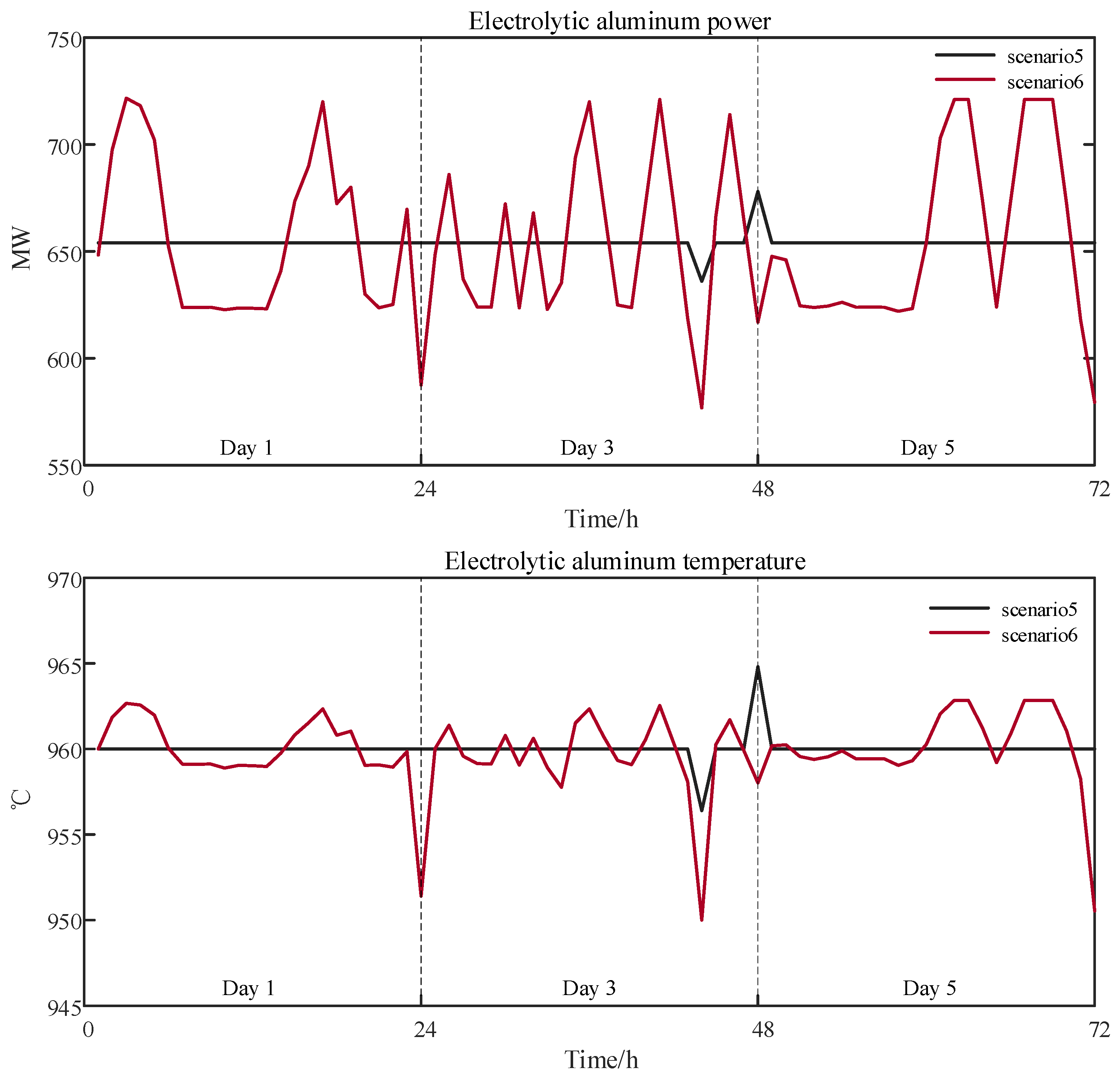

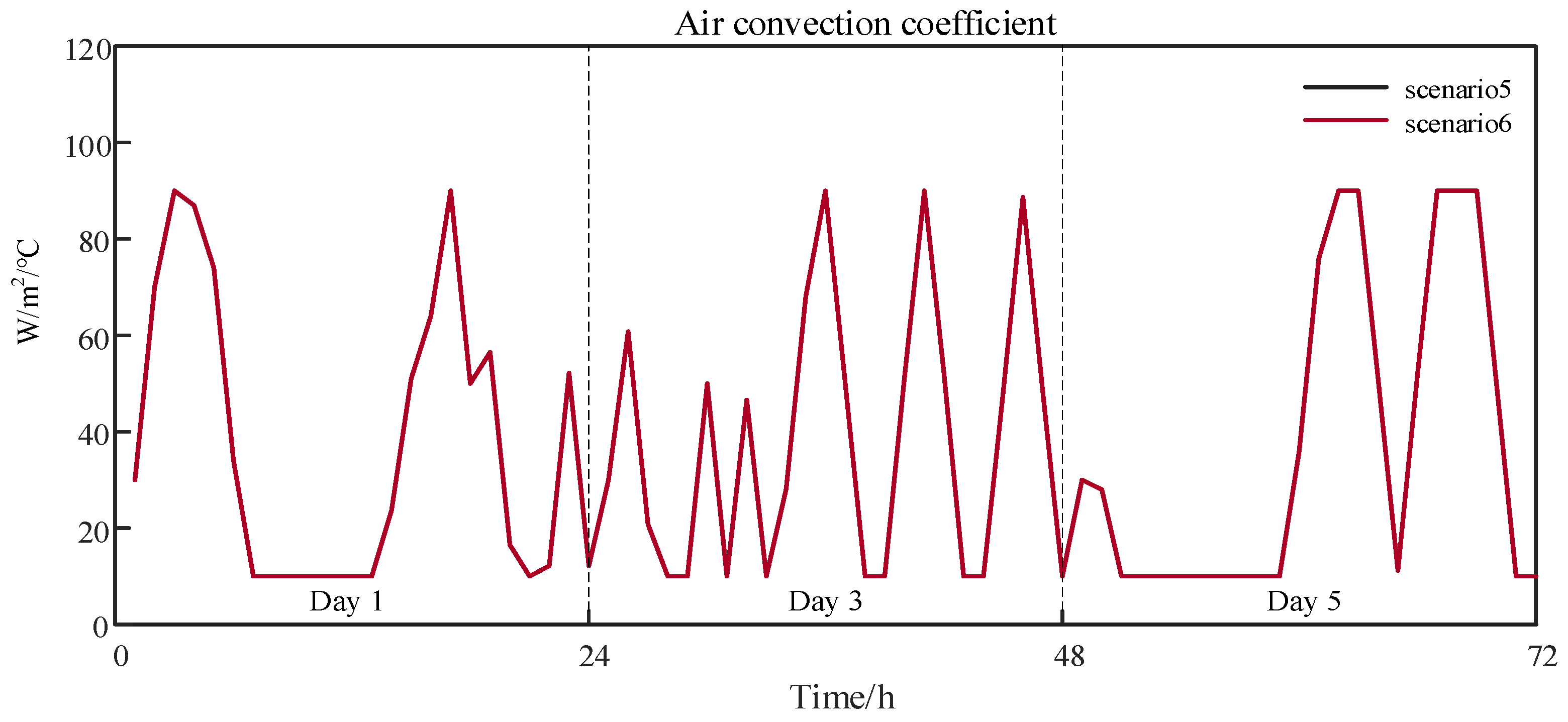

7.1. Effect of Heat Exchangers on Operational Flexibility

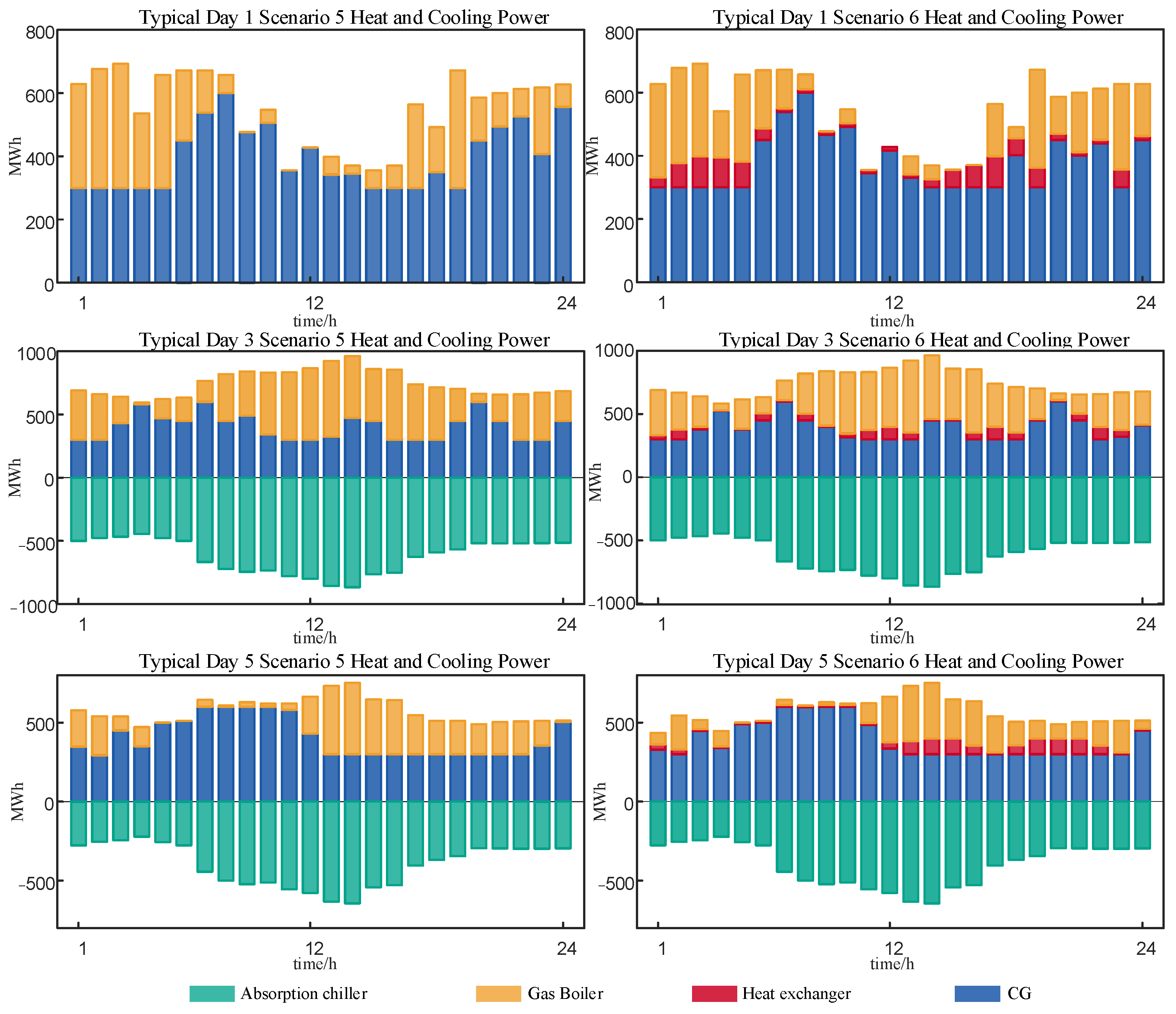

7.2. System Flexibility Enhancement Along with Renewable Integration

7.3. Cost–Benefit Analysis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. Global Energy Review 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- National Development and Reform Commission of China. Guiding Opinions on Vigorously Implementing the Renewable Energy Substitution Action; National Development and Reform Commission of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Paul, S.; Dey, T.; Saha, P.; Dey, S.; Sen, R. Review on the development scenario of renewable energy in different country. In Proceedings of the 2021, Innovations in Energy Management and Renewable Resources(52042), Kolkata, India, 5–7 February 2021; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Chen, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y. Supply-Demand Balance Assessment Method for Power Systems Considering Extreme Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Kunming, China, 16–18 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.; Tao, Z.; Agyekum, E.B.; Fahad, S.; Tahir, M.; Salman, M. Sustainable rural electrification: Energy-economic feasibility analysis of autonomous hydrogen-based hybrid energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 141, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, C.M.; Brigatti, L.G.; Spiller, M.; Rancilio, G.; Merlo, M. Unlocking Grid Flexibility: Leveraging Mobility Patterns for Electric Vehicle Integration in Ancillary Services. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum, W.E. Net-Zero Industry Tracker. 2023. Available online: https://cn.weforum.org/publications/net-zero-industry-tracker-2023/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Liu, J.; Zeng, K.; Wang, C.; Le, L.; Zhang, M.; Ai, X. Unit Commitment Considering Electrolytic Aluminum Load for Ancillary Service. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Intelligent Green Building and Smart Grid (IGBSG), Yichang, China, 6–9 September 2019; pp. 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAFE. Global Insights: Energy and Environmental Aluminum Solutions. 2023. Available online: https://secureenergy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SAF-_CSIM_Aug23_v04.1_singles.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- National Development and Reform Commission (China). Power Demand Side Management Measures (2023 Edition); National Development and Reform Commission: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Su, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, C.; Ai, X. Source-load coordinated optimal scheduling in stochastic unit commitment considered electrolytic aluminum load and wind power uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Nanjing, China, 27–29 May 2022; pp. 2175–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, G.; Gu, P.; Ning, L.; Wang, Z. Optimal operation of energy-intensive load considering electricity carbon market. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.F.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Liao, S. Electrolytic aluminum load participating in power grid frequency modulation method based on active adjustable capacity coordination. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 25–28 March 2021; pp. 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gong, F.; Sun, T.; Yuan, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z. Research on the method of electrolytic aluminum load participating in the frequency control of power grid. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Engineering (ICBAIE), Nanchang, China, 26–28 March 2021; pp. 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, B.; Ding, K.; Sun, Y. Day-ahead economic dispatch of power systems considering the demand response of electrolytic aluminum loads. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Dali, China, 9–11 May 2024; pp. 2207–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Yu, P.; Xu, Z.; Fan, T.; Liu, H.; Yu, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Day-ahead intra-day economic dispatch methodology accounting for the participation of electrolytic aluminum loads and energy storage in power system peaking. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Dali, China, 9–11 May 2024; pp. 2201–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Sun, P.; He, C.; Pi, S.; Liao, S. Real-Time Regulation Boundary Solution Method for Electrolytic Aluminum Industrial Park. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Power Systems and Electrical Technology (PSET), Tokyo, Japan, 5–8 August 2024; pp. 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Dong, C.; Lan, X.; Wang, C.; Le, L.; Ai, X. A Bi-level Programming Guiding Electrolytic Aluminum Load for Demand Response. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Weihai, China, 13–15 July 2020; pp. 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Yan, Z. System Optimization Scheduling Considering the Full Process of Electrolytic Aluminum Production and the Integration of Thermal Power and Energy Storage. Energies 2025, 18, 598. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/18/3/598 (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Shu, H.; Fang, Z.; Mo, X. A Grid-Generator-Electrolytic Aluminum Multi-Agent Cooperative Game Model Based on Nash Negotiation Theory. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140619–140627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C. Coordinated optimization of IES in electrolytic aluminum industrial park considering hybrid CSP-CCHP system, demand response, and CCER-carbon trading. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 171, 110943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Song, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, R.; Xiong, W.; Zhou, R. Cointegration Optimization Scheduling of Integrated Energy Systems for Aluminum Electrolysis Parks Considering Flexible Electric-Thermal Power Balance. 2025. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.2107.tm.20251107.1124.010 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Jia, H.J.; Xu, C.; Jin, X.L.; Mu, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Tang, W. Decision-making for electrolytic aluminum enterprises in electricity-carbon market with GC-CER joint trading. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 49, 4174–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, L.; Zayed, M.E.; Elsheikh, A.H.; Li, W.; Yan, Q.; Wang, J. Industrial reheating furnaces: A review of energy efficiency assessments, waste heat recovery potentials, heating process characteristics and perspectives for steel industry. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 147, 1209–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashtizadeh, E.; Houshfar, E. Comparative thermoeconomic analysis of integrated hybrid multigeneration systems with hydrogen production for waste heat recovery in cement plants. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 89, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gao, W.; Qin, Y. Integration of direct ammonia protonic ceramic fuel cell with thermoacoustic cycle for waste heat recovery: Performance assessment, influential mechanism and multi-objective optimization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 118, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Su, C.; Hu, S.; Li, L.; Li, X. Environmental and life cycle assessment of organic Rankine cycle technology for industrial waste heat recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enterprise | Desired Capacity | Bidding Model |

|---|---|---|

| A | 350 | N(0.40, 0.022) |

| B | 250 | N(0.34, 0.062) |

| C | 400 | N(0.30, 0.022) |

| D | 300 | N(0.25, 0.012) |

| EA | 1000 | - |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Aside | 18 m2 |

| Atop | 10 m2 |

| hside | 10–120 W/m2/°C |

| htop | 30 W/m2/°C |

| Ce | 1800 J/kg/°C |

| me | 600 kg |

| ηAL | 0.75 |

| Device | Unit | Capital Investment (USD) | Lifetime (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-owned PV | MW | 507.38 | 20 |

| Self-owned wind turbine | MW | 1128.34 | 20 |

| Heat exchanger | unit | 70,521.86 | 20 |

| Scenario | Heat Exchanger | Self-Owned PV and Wind | Green Certificate Trading | External Wind Bidding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | × | × | × | × |

| 2 | √ | × | × | × |

| 3 | √ | √ | × | × |

| 4 | √ | √ | √ | × |

| 5 | × | √ | √ | √ |

| 6 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 7 | √ | √ | √ | average price |

| Scenario | Configuration (HX/Wind/PV/EW) | Cost (108 USD) | Revenue (108 USD) | Emission (106 t) | Green Al (%) | RES Integration (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | –/–/– | 0.0000 | 3.2843 | 4.1207 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 166/0/0/0 | 0.0337 | 3.3349 | 4.1207 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 176/310/244.5/0 | 0.9598 | 4.2829 | 3.2111 | 27.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 332/887.9/137.6/0 | 1.6462 | 6.5848 | 2.1621 | 56.1 | 93.2 |

| Scenario | Configuration (HX/Wind/PV/EW) | Cost (108 USD) | Revenue (108 USD) | Emission (106 t) | Green Al (%) | RES Integration (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0/928.9/110.5/0 | 2.1204 | 6.2045 | 2.0830 | 57.1 | 84.3 |

| 6 | 340/928.9/110.5/1000 | 2.1849 | 6.8161 | 1.9802 | 60.4 | 88.3 |

| 7 | 340/930.1/111.5/324 | 2.1880 | 6.7939 | 2.0574 | 57.3 | 91.7 |

| Scenario | PV Installation Cost (USD/kW) | WT Installation Cost (USD/kW) | Net Present Value (108 USD) | Levelized Cost of Energy (USD/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark case prices | 507.38 | 1128.34 | 4.6298 | 0.0496 |

| 2024 China average prices | 652.89 | 1331.45 | 4.2973 | 0.0587 |

| Benchmark case prices +20% | 609.31 | 1354.02 | 4.3556 | 0.0594 |

| Benchmark case prices −20% | 406.21 | 902.68 | 4.9549 | 0.0398 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, R. Co-Planning of Electrolytic Aluminum Industrial Parks with Renewables, Waste Heat Recovery, and Wind Power Subscription. Sustainability 2026, 18, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010297

Yang Y, Liu W, Zhang Z, Yan Z, Zhang R. Co-Planning of Electrolytic Aluminum Industrial Parks with Renewables, Waste Heat Recovery, and Wind Power Subscription. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010297

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yulong, Weiyang Liu, Zihang Zhang, Zhongwen Yan, and Ruiming Zhang. 2026. "Co-Planning of Electrolytic Aluminum Industrial Parks with Renewables, Waste Heat Recovery, and Wind Power Subscription" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010297

APA StyleYang, Y., Liu, W., Zhang, Z., Yan, Z., & Zhang, R. (2026). Co-Planning of Electrolytic Aluminum Industrial Parks with Renewables, Waste Heat Recovery, and Wind Power Subscription. Sustainability, 18(1), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010297