Environmental Regulation and Urban Ecological Welfare Performance in China: Evidence from the Key Cities for Air Pollution Control Policy

Abstract

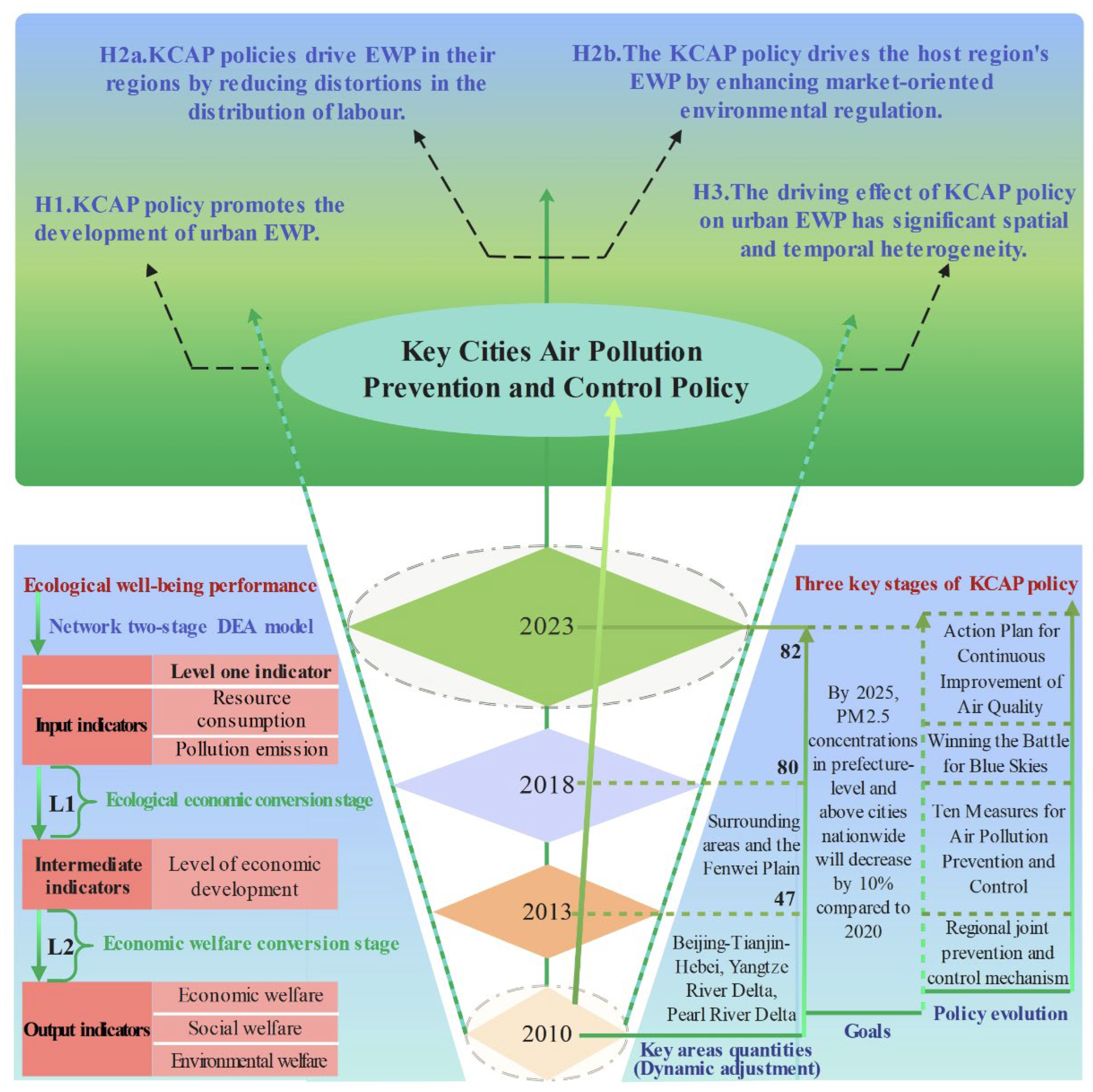

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Hypotheses

3. Description of Model Specification and Variables

3.1. Model Specification

- (1)

- As major cities targeted by air pollution control initiatives are set up in batches, referring to a previous study, this paper utilizes a progressive DID method to account for temporal variations in policy implementation. The specification is as follows [43]:

- (2)

- Using the event study method, we estimate KCAP’s dynamic effects:

- (3)

- Following the previous study, we model the spatial heterogeneity of KCAP effects [44]:

3.2. Variable Description

3.2.1. EWP

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Mediating Variables

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Baseline Regression

4.3. Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity Test

- (1)

- Time heterogeneity test: To verify the dynamic change characteristics of the KCAP policy’s driving effect on urban EWP as hypothesized in Hypothesis 3, Figure 2 presents the time trend of the coefficient of variable in Equation (2) at the 95% confidence level. The results show that, in the first two years after the policy implementation, the promoting effect of the KCAP policy on EWP was significantly positive; however, after two years, this effect gradually weakened and tended to be insignificant. This indicates that the driving effect of the KCAP policy on urban EWP has short-term timeliness, and its long-term impact has not been sustained. In the early stage of policy implementation, local governments, under the pressure of strict supervision and assessment, tended to respond quickly through short-term measures such as concentrating on shutting down highly polluting enterprises and strengthening industry emission control. However, as the inspection period comes to an end and the intensity of supervision weakens, the focus of local governance may shift towards economic growth and investment attraction, leading to a decrease in the intensity of environmental protection law enforcement and a subsequent decline in the effectiveness of pilot policies. From the perspective of emission reduction paths, in the early stage, low-cost emission reduction can be achieved by eliminating backward production capacity, promoting the rapid improvement in urban EWP. However, long-term reliance on this model will lead to insufficient impetus for industrial structure upgrading and make it difficult to support the continuous improvement in EWP. Furthermore, without a market-based pricing mechanism, long-term incentive policies, and public participation channels, the environmental protection behaviors of enterprises and residents are mostly short-term passive cooperation, making it difficult to form a stable green development model and further hindering the improvement in EWP.

- (2)

- Spatial heterogeneity test: Figure 3 plots the estimated coefficients of from Ns from Equation (3) with 95% confidence intervals to illustrate how the implications of the KCAP policy on adjacent cities’ EWP differ across geographic distances. The results reveal a “∽” type trend: As proximity to KCAP cities decreases, the policy-induced positive external impact on neighboring cities’ EWP initially weakens, then strengthens, and eventually declines again. Among them, the agglomeration shadow area of air pollution control pilot cities is within 70 km of their own cities, which will have a significant driving effect on the surrounding cities’ EWP within 70–80 km, and after 80 km, the driving effect of air pollution control pilot cities on the surrounding cities’ EWP will become insignificant. This also verifies the spatial heterogeneity of the regional EWP driving effect of pilot cities under the air pollution control program in Hypothesis 3.

4.4. Robustness Test

- (1)

- It is unclear whether the designation of key cities for air quality management is subject to reverse causality driven by their EWP. To test the DID assumption, we follow the previous study and construct the following risk model [57]:

- (2)

- Common trend hypothesis test: A key assumption of staggered DID is parallel pre-policy EWP trends between treatment and control groups. In order to test this common trend hypothesis, this paper makes an empirical analysis by using Formula (2). According to the results in Figure 2, the coefficients of the variables before the establishment of air pollution control pilot cities are statistically insignificant, indicating no pre-policy EWP differences between groups and thereby satisfying the parallel trend assumption.

- (3)

- Sample selection bias is addressed via PSM-DID: Given the phased policy rollout, 50 cities selected during the sample period are defined as the treatment group. To construct a comparable control group, the PSM method is employed using 1:3 nearest-neighbor matching with replacement. The results of the test are shown in Table 5 and Table 6, where the difference in covariates for late matching is not statistically significant, confirming the balance between groups. In addition, regression estimates using the PSM-matched sample confirm that the DID coefficient continues to be significant at the 1% level.

- (4)

- Mitigating potential endogeneity and clustering issues: To address potential endogeneity, all control variables are lagged by one period. The L.control result in column (3) of Table 6 still shows a positive correlation at the 1% level.

- (5)

- IV Methodology: There may be a strong correlation between the identification of the list of model cities and the level of urban EWP, leading to a two-way causality problem and thus affecting the accuracy of the benchmark results. Therefore, to address the endogeneity issue, urban river density was used as an instrumental variable for the KCAP policy. In terms of correlation, river density is directly related to watershed area, and the larger the watershed area, the easier it is for the city to be regulated by the higher or central government, resulting in a better chance of becoming a model city. In terms of exogeneity, river density is dependent on local geographic conditions, neither of which directly affects urban EWP. In addition, given that river density data do not vary over time, this paper cross-multiplies it with a time trend term as an instrumental variable (IV_River). This paper estimates the instrumental variable results for river density. In the first stage regression, the coefficients of the instrumental variables are all statistically significant, indicating that they are strongly correlated with model city construction. On the city-level panel data, both Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F-statistic (43.947) and Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic (6248.97) are higher than the critical value of 16.38 at the 10% level of F, suggesting that there is no weak instrumental variable. All the above tests prove that our instrumental variables are reliable. In column (2) of Table 7, the DID coefficient is significantly positive, indicating that the KCAP policy still has a significant uplift effect on urban EWP after accounting for endogeneity issues, which is not significantly different from the benchmark regression results.

- (6)

- Placebo test: To further ensure that the observed policy effects are not driven by unobserved shocks or model misspecification, two placebo exercises are conducted. ① Randomized Treatment and Control Groups: We treat the original KCAP policy cities as a new control group and, holding the actual implementation years constant, randomly select an equal number () of untreated cities each year from the pool of never-treated cities to form a new treatment group. Using this pseudo-sample, we re-estimate Model (2) in Table 3. Repeating the above process 1000 times to estimate the coefficients for 1000 DID. The average placebo coefficient is 0.0074 × 10−4, far smaller than the baseline estimate of 0.0133, indicating that the true KCAP policy effect is strongly location-specific and most pronounced for the officially designated cities. ② Randomly Advancing the Policy Start Year: Keeping the set of KCAP policy cities unchanged, we randomly draw a year from the interval for each treated city—where is the actual implementation year—and assign this pseudo-year as the policy start date. Using the resulting pseudo-sample, we again re-estimate Model (2) and repeat procedure 1000 times. The average placebo coefficient is 0.0040 × 10−2, roughly 99.7 percent smaller than the baseline estimate. Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of these placebo estimates and their associated p-values. The pronounced attenuation of the effect when treatment timing is randomly advanced provides compelling counterfactual evidence that the actual KCAP policy designations genuinely enhanced EWP in the treated cities. Together, these placebo tests corroborate the stability of the main estimation results and reinforce the causal interpretation of KCAP policy’s positive impact on urban EWP.

- (7)

- Outlier test: Table 8 tests the robustness from the following four aspects: ① According to the outliers of the modified EWP, the maximum and minimum 1% samples of EWP are truncated, and the model (1) reports the corresponding test results; ② Model (2) controls for province and year fixed effects; Model (3) adds city fixed effects; Model (4) additionally includes province-year interactions. Overall, the DID coefficient remains significant.

- (8)

- Accounting for the impact of other geographically targeted policy measures: The selection of KCAP is frequently shaped by multiple spatially targeted national policies. To mitigate the confounding effects of such policies, this paper identifies and controls for three primary categories of national location-oriented policy measures: ① The influence of pilot policies on peak carbon dioxide emissions. Among the 50 air pollution control pilot cities set up in this sample, 6 cities are covered by the carbon peak pilot, so their influence must be excluded. ② Two of the 50 KCAP cities also adopted the carbon trading pilot, potentially confounding its effect on local EWP. To address potential confounding, this study excludes two pilot cities that overlap with national air pollution control targets. On the basis of benchmark regression, this paper introduces two pilot policy variables as control variables, respectively, and brings the cities targeted by key national air pollution governance policies and these two pilot policies into the regression model in parallel. Table 9 shows the regression results, in which column (3) reports the regression results of strategically selected cities for environmental governance and two pilot policies. It is evident that the establishment of designated air pollution control cities significantly promotes the growth of local EWP. Accordingly, the observed increase in a host city’s EWP is attributable to its designation as a key air-pollution-control city, rather than to other contemporaneous policy measures.

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

4.6. Heterogeneity Test

4.6.1. Pollution Levels: Regulatory Pressure and Innovation Potential Channels

4.6.2. Industrial Base: A Channel for Structural Transformation

4.6.3. City Size: Institutional Capacity and Economic Channels of Agglomeration

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Regions |

|---|---|

| 2007 | Directly administered municipalities: Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing; Provincial capital cities: Shijiazhuang, Taiyuan, Hohhot, Shenyang, Changchun, Harbin, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Hefei, Fuzhou, Nanchang, Jinan, Zhengzhou, Wuhan, Changsha, Guangzhou, Nanning, Haikou, Chengdu, Guiyang, Kunming, Lhasa, Xi’an, Lanzhou, Xining, Yinchuan, Urumqi; Planned cities: Dalian, Qingdao, Ningbo, Xiamen, Shenzhen; Other cities: Qinhuangdao, Tangshan, Baoding, Handan, Changzhi, Linfen, Yangquan, Datong, Baotou, Chifeng, Anshan, Fushun, Benxi, Jinzhou, Jilin, Mudanjiang, Qiqihar, Daqing, Suzhou, Nantong, Lianyungang, Wuxi, Changzhou, Yangzhou, Xuzhou, Wenzhou, Jiaxing, Shaoxing, Taizhou, Huzhou, Ma’anshan, Wuhu, Quanzhou, Jiujiang, Yantai, Zibo, Tai’an, Weihai, Zaozhuang, Jining, Weifang, Rizhao, Luoyang, Anyang, Jiaozuo, Kaifeng, Pingdingshan, Jingzhou, Yichang, Yueyang, Xiangtan, Zhangjiajie, Zhuzhou, Changde, Zhanjiang, Zhuhai, Shantou, Foshan, Zhongshan, Shaoguan, Guilin, Beihai, Sanya, Liuzhou, Mianyang, Panzhihua, Luzhou, Yibin, Zunyi, Qujing, Xianyang, Yan’an, Baoji, Tongchuan, Jinchang, Shizuishan, Karamay. |

| 2013 | Beijing, Tianjin, Shijiazhuang, Tangshan, Baoding, Langfang, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuxi, Changzhou, Suzhou, Nantong, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Jiaxing, Huzhou, Shaoxing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Jiangmen, Zhaoqing, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Shenyang, Jinan, Qingdao, Zibo, Weifang, Rizhao, Wuhan, Changsha, Chongqing, Chengdu, Fuzhou, Sanming, Taiyuan, Xi’an, Xianyang, Lanzhou, Yinchuan, Urumqi. |

| 2018 | Beijing, Tianjin, Shijiazhuang, Tangshan, Langfang, Baoding, Cangzhou, Hengshui, Xingtai, Handan, Xiongan New Area, Xinji, Dingzhou, Taiyuan, Yangquan, Changzhi, Jincheng, Jinan, Zibo, Jining, Dezhou, Liaocheng, Binzhou, Heze, Zhengzhou, Kaifeng, Anyang, Hebi, Xinxiang, Jiaozuo, Puyang, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Suzhou, Nantong, Lianyungang, Huaian, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Suqian, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Jiaxing, Huzhou, Shaoxing, Zhoushan, Hefei, Wuhu, Bengbu, Huainan, Ma’anshan, Huaibei, Chuzhou, Fuyang, Suzhou, Liu’an, Bozhou, Taiyuan, Yangquan, Changzhi, Jincheng, Jinzhong, Yuncheng, Linfen, Luliang, Xi’an, Tongchuan, Baoji, Xianyang, Weinan, Yangling Agricultural Hi-Tech Industrial Demonstration Zone, Hancheng. |

| 2023 | Beijing, Tianjin, Shijiazhuang, Tangshan, Qinhuangdao, Handan, Xingtai, Baoding, Cangzhou, Langfang, Hengshui, Xiongan New Area, Xinji, Dingzhou, Jinan, Zibo, Zaozhuang, Dongying, Weifang, Jining, Tai’an, Rizhao, Linyi, Dezhou, Liaocheng, Binzhou, Heze, Zhengzhou, Kaifeng, Luoyang, Pingdingshan, Anyang, Hebi, Xinxiang, Jiaozuo, Puyang, Xuchang, Luohe, Sanmenxia, Shangqiu, Zhoukou, Jiyuan, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Changzhou, Suzhou, Nantong, Lianyungang, Huai’an, Yancheng, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Taizhou, Suqian, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Jiaxing, Huzhou, Shaoxing, Zhoushan, Hefei, Wuhu, Bengbu, Huainan, Ma’anshan, Huaibei, Chuzhou, Fuyang, Suzhou, Liu’an, Bozhou, Taiyuan, Yangquan, Changzhi, Jincheng, Jincheng, Yuncheng, Linfen, Lvliang, Xian, Tongchuan, Baoji, Xianyang, Weinan, Yangling Agricultural Hi-Tech Industrial Demonstration Zone, Hancheng |

Appendix B

| Range Types | City |

|---|---|

| Prefecture-level cities (95) | Hebei Province (6): Zhangjiakou, Tangshan, Baoding, Xingtai, Handan, Chengde; Shanxi Province (5): Datong, Yangquan, Changzhi, Jinzhong, Linfen; Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2): Baotou, Chifeng; Liaoning Province (11): Anshan, Fushun, Benxi, Jinzhou, Yingkou, Fuxin, Liaoyang, Tieling, Chaoyang, Panjin, Huludao; Jilin Province (6): Jilin, Siping, Liaoyuan, Tonghua, Baishan, Baicheng; Heilongjiang Province (6): Qiqihar, Mudanjiang, Jiamusi, Daqing, Jixi, Yichun; Jiangsu Province (3): Xuzhou, Changzhou, Zhenjiang; Anhui Province (6): Huaibei, Bengbu, Huainan, Wuhu, Ma’anshan, Anqing; Jiangxi Province (3): Jiujiang, Jingdezhen, Pingxiang; Shandong Province (2): Zibo, Zaozhuang; Henan Province (8): Kaifeng, Luoyang, Pingdingshan, Anyang, Hebi, Xinxiang, Jiaozuo, Nanyang; Hubei Province (6): Huangshi, Xiangyang, Jingzhou, Yichang, Shiyan, Jingmen; Hunan Province (6): Zhuzhou, Xiangtan, Hengyang, Yueyang, Shaoyang, Loudi; Guangdong Province (2): Shaoguan, Maoming; Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (2): Liuzhou, Guilin; Sichuan Province (8): Zigong, Panzhihua, Luzhou, Deyang, Mianyang, Neijiang, Leshan, Yibin; Guizhou Province (3): Zunyi, Anshun, Liupanshui; Shaanxi Province (4): Baoji, Xianyang, Tongchuan, Hanzhong; Gansu Province (4): Tianshui, Jiayuguan, Jinchang, Baiyin; Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (1): Shizuishan; Karamay, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (1). |

| Municipalities directly under the central government, cities specifically designated in the state plan, and provincial capital cities (25) | Shijingshan District of Beijing, Yuantanggu District of Tianjin, Minhang District of Shanghai, Dadukou District of Chongqing, Chang’an District of Shijiazhuang, Wanbailin District of Taiyuan, Dadong District of Shenyang, Wafangdian City of Dalian, Kuancheng District of Changchun, Xiangfang District of Harbin, Yuandachang District of Nanjing, Yaohai District of Hefei, Qingyunpu District of Nanchang, Licheng District of Jinan, Zhongyuan District of Zhengzhou, Qiaokou District of Wuhan, Kaifu District of Changsha, Qingbaijiang District of Chengdu, Xiaohe District of Guiyang, Wuhua District of Kunming, Baqiao District of Xi’an, Qilihe District of Lanzhou, Chengzhong District of Xining, Xixia District of Yinchuan, and Toutunhe District of Urumqi. |

References

- Chen, G.; Li, S.; Knibbs, L.D.; Hamm, N.A.; Cao, W.; Li, T.; Guo, Y. A machine learning method to estimate PM2.5 concentrations across China with remote sensing, meteorological, and land use information. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Q.; Liu, G.; Lau, A.K.H.; Li, Y.; Li, C.C.; Fung, J.C.H.; Lao, X.Q. High-resolution satellite remote sensing of provincial PM2.5 trends in China from 2001 to 2015. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 180, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, X.; Sayer, A.M.; Levy, R.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y. Satellite-based spatiotemporal trends in PM2.5 concentrations: China, 2004–2013. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 124, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, G.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, D.; Hao, J. Rapid improvement of PM2.5 pollution and associated health benefits in China during 2013–2017. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Lu, Y. Inter-city air pollutant transport in The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration: Comparison between the winters of 2012 and 2016. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Han, X. A review of surface ozone source apportionment in China. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2020, 13, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, D.; Shi, Q.; Cheng, M. Which countries are more ecologically efficient in improving human well-being? An application of the Index of Ecological Well-being Performance. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 129, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhong, S.; Li, Q.; Zhao, X.; Dong, X. Ecological well-being performance growth in China (1994–2014): From perspectives of industrial structure green adjustment and green total factor productivity. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Jorgenson, A.K. Towards a new view of sustainable development: Human well-being and environmental stress. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Steady-state economics versus growthmania: A critique of the orthodox conceptions of growth, wants, scarcity, and efficiency. Policy Sci. 1974, 5, 149–167. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4603736 (accessed on 19 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Rosa, E.A.; York, R. Environmentally efficient well-being: Is there a Kuznets curve? Appl. Geogr. 2010, 32, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Yu, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, X.C.; Klemeš, J.J.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y. Sustainability evaluation based on the Three-dimensional Ecological Footprint and Human Development Index: A case study on the four island regions in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 265, 110509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Sarwar, S.; Li, Z.; Zhou, N. Spatio-temporal evolution and driving effects of the ecological intensity of urban well-being in the Yangtze River Delta. Energy Environ. 2022, 33, 1181–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, S.; Guo, J.; Peng, S.; Qie, X.; Yu, Z.; Li, P. Exploring ways to improve China’s ecological well-being amidst air pollution challenges using mixed methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z. Ecological well-being performance and influencing factors in China: From the perspective of income inequality. Kybernetes 2021, 52, 1269–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhong, J. An empirical analysis of the coupling and coordinated development of new urbanization and ecological welfare performance in China’s Chengdu–Chongqing economic circle. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ling, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Deng, N. Can air quality ecological compensation improve environmental welfare performance? Based on the “Win–Win–Win” perspective of economy–ecology–welfare. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 489, 144604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, D.; Zhou, S.; Han, Z. Towards sustainable development: Assessing the effects of low-carbon city pilot policy on residents’ welfare. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dai, C.; Wei, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhou, J. Air pollution prevention and control action plan substantially reduced PM2.5 concentration in China. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Pan, X.; Guo, X.; Li, G. Health impact of China’s Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan: An analysis of national air quality monitoring and mortality data. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e313–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Huang, Z.; Bilal, M.; Assiri, M.; Mhawish, A.; Nichol, J.; Leeuw, G.D.; Almazroui, M.; Wang, Y.; Alsubhi, Y. Long-term PM2.5 pollution over China: Identification of PM2.5 pollution hotspots and source contributions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 893, 164871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N.; Ma, F.; Qin, C.B.; Li, Y.F. Spatiotemporal trends in PM2.5 levels from 2013 to 2017 and regional demarcations for joint prevention and control of atmospheric pollution in China. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ying, Q.; Zhang, H. Spatial and temporal variability of PM2.5 and PM10 over the North China Plain and the Yangtze River Delta, China. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 95, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shao, S.; Tian, Z.; Xie, Z.; Yin, P. Impacts of air pollution and its spatial spillover effect on public health based on China’s big data sample. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 142, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, H.; Salvo, A. Severe Air Pollution and Labor Productivity: Evidence from Industrial Towns in China. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2019, 11, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, T.; Yagil, J. Air pollution and stock returns in the US. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011, 32, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, J.V.; Rabl, A. Damage costs due to automotive air pollution and the influence of street canyons. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 4763–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, S.; Chang, X.; Hao, J. The impact of the “air pollution prevention and control action plan” on PM2.5 concentrations in the Jing-Jin-Ji region during 2012–2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 580, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Dong, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X. Is the key-treatment-in-key-areas approach in air pollution control policy effective? Evidence from the action plan for air pollution prevention and control in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 843, 156850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q. Job destruction and creation: Labor reallocation entailed by the clean air action in China. China Econ. Rev. 2023, 79, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Nicholls, J.F.G. Measurement of labor reallocation effect in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 197, 122925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Du, W. The impact of environmental regulation on the employment of enterprises: An empirical analysis based on scale and structure effects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 21705–21716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, L. The effect of heterogeneous environmental regulations on the employment skill structure: The system-GMM approach and mediation model. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, R.H.; Yuan, Y.J.; Huang, J.J. Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on “green” productivity: Evidence from China. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 132, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Han, X. Heterogeneous two-sided effects of different types of environmental regulations on carbon productivity in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gao, D.; Li, Y. Impacts of market-based environmental regulation on green total factor energy efficiency in China. China World Econ. 2023, 31, 92–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Du, H.; Lin, Z.; Zuo, J. Spatial spillover effects of environmental regulations on air pollution: Evidence from urban agglomerations in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 272, 110998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P.; Moretti, E. People, places, and public policy: Some simple welfare economics of local economic development programs. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2014, 6, 629–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busso, M.; Gregory, J.; Kline, P. Assessing the incidence and efficiency of a prominent place based policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 897–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, B.A.; Glaeser, E.L.; Summers, L.H. Jobs for the Heartland: Place-Based Policies in 21st Century America; No. 24548; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Briant, A.; Lafourcade, M.; Schmutz, B. Can tax breaks beat geography? Lessons from the French enterprise zone experience. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2015, 7, 88–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.J.; Montouri, B.D. US regional income convergence: A spatial econometric perspective. Reg. Stud. 1999, 33, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. The economic impact of special economic zones: Evidence from Chinese municipalities. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 101, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, S.; Shao, L.; Zilibotti, F. Economic reforms and industrial policy in a panel of Chinese cities. J. Econ. Growth 2016, 21, 305–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.; Hwang, S.N. Efficiency decomposition in two-stage data envelopment analysis: An application to non-life insurance companies in Taiwan. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 185, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibas, R.; Chateau, J.; Dellink, R.; Lanzi, E. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060: Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. HM Treasury 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Dyckhoff, H.; Allen, K. Measuring ecological efficiency with data envelopment analysis (DEA). Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 132, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 167, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togtokh, C. Time to stop celebrating the polluters. Nature 2011, 479, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, W.; Chen, D. Progress of China’s new-type urbanization construction since 2014: A preliminary assessment. Cities 2018, 78, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degu, A.A.; Huluka, A.T. Does the Declining Share of Agricultural Output in GDP Indicate Structural Transformation? The Case of Ethiopia. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2019, 11, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Martinez-Vazquez, J.; Wu, A.M. Fiscal decentralization, equalization, and intra-provincial inequality in China. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2016, 24, 248–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, D.H. The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 2121–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasraei, A.; Garmabaki, A.H.S.; Odelius, J.; Famurewa, S.M.; Chamkhorami, K.S.; Strandberg, G. Climate change impacts assessment on railway infrastructure in urban environments. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 101, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhu, S. Digital economy, scientific and technological innovation, and high-quality economic development: A mediating effect model based on the spatial perspective. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Criterion Layer | Indicator Layer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial investment | Input end resource consumption | Energy consumption | Per capita electricity consumption in kilowatt-hours |

| Land consumption | Per capita urbanized land area/square meter | ||

| Water resource consumption | Per capita freshwater use per cubic meter | ||

| Output end pollution emissions | Wastewater discharge | Per capita discharge of industrial effluents/ton | |

| Exhaust emissions | Per capita SO2 emissions from industrial sources/ton | ||

| Solid waste discharge | Per person volume of urban solid waste managed/ton | ||

| Intermediate variable | Level of economic development | Personal income | Per person GDP/10,000 yuan |

| Public revenue | Per person public revenue/10,000 yuan | ||

| Final output | Economic welfare | Consumption level | Per capita total retail sales of consumer goods/10,000 yuan Number of persons with tertiary education per 10,000 people |

| Social welfare | Educational level | ||

| Medical hygiene | Number of hospitals per 10,000 people | ||

| Hospital beds per 10,000 inhabitants | |||

| Physicians per 10,000 population | |||

| Environmental welfare | Environmental benefit | Per capita public green space/meter | |

| Number of parks per 10,000 people | |||

| Centralized sewage treatment rate/% | |||

| Safe disposal rate of household waste/% | |||

| Variable | Obs | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EWP | 3519 | 0.0514 | 0.0437 | 0.0014 | 0.3811 |

| DID | 3519 | 0.1182 | 0.3229 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| People | 3519 | 1.9234 | 2.0210 | 0.0300 | 36.0700 |

| Urban | 3519 | 46.3277 | 25.2478 | 0.0000 | 508.1930 |

| Fisdecentra | 3519 | 1.2465 | 1.5270 | 0.0676 | 20.8904 |

| Number | 3519 | 1.3406 | 5.3037 | 0.0040 | 150.4640 |

| Export | 3519 | 0.3863 | 1.7034 | 0.0000 | 33.6686 |

| Passenger | 3519 | 0.8981 | 2.9388 | 0.0000 | 78.3030 |

| Primary | 3519 | 0.1281 | 0.0789 | 0.0020 | 0.4989 |

| Tec | 3519 | 0.7677 | 2.6189 | 0.0047 | 52.8052 |

| Revenue | 3519 | 3.6864 | 5.6775 | 0.0002 | 96.6959 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| EWP | EWP | |

| DID | 0.0170 *** | 0.0133 *** |

| (0.0048) | (0.0051) | |

| People | 0.0044 ** | |

| (0.0021) | ||

| Urban | −0.0004 ** | |

| (0.0001) | ||

| Fisdecentra | 0.0112 *** | |

| (0.0030) | ||

| Number | −0.0005 ** | |

| (0.0002) | ||

| Export | 0.0011 * | |

| (0.0006) | ||

| Passenger | 0.0006 *** | |

| (0.0001) | ||

| Primary | −0.0426 | |

| (0.0321) | ||

| Tec | 0.0007 | |

| (0.0012) | ||

| Revenue | 0.0007 ** | |

| (0.0003) | ||

| Constant | 0.0494 *** | 0.0465 *** |

| (0.0006) | (0.0062) | |

| Year | YES | YES |

| City | YES | YES |

| N | 3519 | 3519 |

| R2 | 0.7313 | 0.7423 |

| Variable | lnT |

|---|---|

| EWP | −1.0547 |

| (0.7680) | |

| Gec | 0.0000 |

| (0.0000) | |

| Market | −0.0751 |

| (0.0838) | |

| People | 0.0869 |

| (0.0752) | |

| Urban | −0.0066 |

| (0.0057) | |

| Fisdecentra | −0.0804 |

| (0.0628) | |

| Number | 0.0002 |

| (0.0075) | |

| Export | 0.0155 |

| (0.0142) | |

| Passenger | −0.0133 |

| (0.0100) | |

| Primary | −0.1629 |

| (0.5204) | |

| Tec | 0.0298 |

| (0.0265) | |

| Revenue | −0.0030 |

| (0.0021) | |

| Constant | 3.1445 |

| (2.1802) | |

| N | 677 |

| Variable | Unmatched | Mean | %reduct | t-test | V(T)/ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched | Treated | Control | %bias | |bias| | t | p > |t| | V(C) | |

| People | U | 3.387 | 1.727 | 69.5 | 16.31 | 0.00 | 2.56 * | |

| M | 3.100 | 3.041 | 2.5 | 96.5 | 0.29 | 0.771 | 0.62 * | |

| Urban | U | 54.130 | 45.282 | 33.1 | 6.75 | 0.000 | 1.37 * | |

| M | 53.147 | 52.112 | 3.9 | 88.3 | 0.43 | 0.668 | 0.57 * | |

| Fisdecentra | U | 2.472 | 1.082 | 58.2 | 18.24 | 0.000 | 10.12 * | |

| M | 1.953 | 2.011 | −2.5 | 95.8 | −0.39 | 0.699 | 0.35 * | |

| Number | U | 4.814 | 0.875 | 38.7 | 14.65 | 0.000 | 74.58 * | |

| M | 2.440 | 2.423 | 0.2 | 99.6 | 0.07 | 0.947 | 0.39 * | |

| Export | U | 1.262 | 0.269 | 43.9 | 11.37 | 0.000 | 3.91 * | |

| M | 0.860 | 0.956 | −4.2 | 90.3 | −0.59 | 0.556 | 0.46 * | |

| Passenger | U | 1.983 | 0.753 | 40.9 | 8.09 | 0.000 | 1.17 | |

| M | 1.566 | 1.404 | 5.4 | 86.8 | 1.03 | 0.304 | 1.08 | |

| Primary | U | 0.074 | 0.135 | −94.9 | −15.29 | 0.000 | 0.30 * | |

| M | 0.077 | 0.074 | 5.8 | 93.8 | 1.26 | 0.206 | 1.04 | |

| Tec | U | 2.981 | 0.471 | 53.3 | 19.31 | 0.000 | 33.87 * | |

| M | 1.752 | 1.714 | 0.8 | 98.5 | 0.19 | 0.851 | 0.43 * | |

| Revenue | U | 7.403 | 3.188 | 55.2 | 14.64 | 0.000 | 4.35 * | |

| M | 5.859 | 6.273 | −5.4 | 90.2 | −0.84 | 0.399 | 0.26 * | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | EWP | EWP | EWP |

| DID | 0.0147 *** | 0.0131 *** | 0.0134 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0050) | (0.0051) | |

| People | 0.0029 | 0.0329 | |

| (0.0044) | (0.0457) | ||

| Urban | −0.0003 | −0.0001 | |

| (0.0003) | (0.0001) | ||

| Fisdecentra | 0.0111 ** | 0.0087 ** | |

| (0.0045) | (0.0041) | ||

| Number | −0.0014 | −0.0008 | |

| (0.0012) | (0.0005) | ||

| Export | 0.0012 | −0.0101 ** | |

| (0.0010) | (0.0043) | ||

| Passenger | 0.0011 | 0.0006 | |

| (0.0008) | (0.0006) | ||

| Primary | −0.0918 | 0.0022 | |

| (0.1445) | (0.0328) | ||

| Tec | 0.0001 | 0.0021 * | |

| (0.0018) | (0.0013) | ||

| Revenue | 0.0011 * | 0.0005 * | |

| (0.0007) | (0.0003) | ||

| L.People | −0.0263 | ||

| (0.0446) | |||

| L.Urban | −0.0005 *** | ||

| (0.0002) | |||

| L.Fisdecentra | 0.0023 | ||

| (0.0040) | |||

| L.Number | 0.0005 | ||

| (0.0006) | |||

| L.Export | 0.0104 *** | ||

| (0.0036) | |||

| L.Passenger | 0.0001 | ||

| (0.0007) | |||

| L.Primary | −0.0517 * | ||

| (0.0301) | |||

| L.Tec | −0.0018 ** | ||

| (0.0008) | |||

| L.Revenue | 0.0003 | ||

| (0.0002) | |||

| Constant | 0.0602 *** | 0.0500 *** | 0.0510 *** |

| (0.0018) | (0.0164) | (0.0073) | |

| Year | YES | YES | YES |

| City | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1108 | 1108 | 3312 |

| R2 | 0.7791 | 0.7889 | 0.7451 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| DID | EWP | |

| IV_River | 2.6861 *** | |

| (0.4052) | ||

| DID | 0.0103 ** | |

| (0.0048) | ||

| People | −0.0036 | 0.0048 ** |

| (0.0130) | (0.0021) | |

| Urban | −0.0009 | −0.0004 ** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0001) | |

| Fisdecentra | 0.0564 * | 0.0111 *** |

| (0.0317) | (0.0030) | |

| Number | −0.0187 *** | −0.0006 *** |

| (0.0035) | (0.0002) | |

| Export | −0.0074 | 0.0009 |

| (0.0092) | (0.0007) | |

| Passenger | −0.0011 | 0.0006 *** |

| (0.0012) | (0.0001) | |

| Primary | −0.3462 | −0.0438 |

| (0.2375) | (0.0319) | |

| Tec | −0.0148 | 0.0008 |

| (0.0139) | (0.0011) | |

| Revenue | 0.0046 * | 0.0007 ** |

| (0.0027) | (0.0003) | |

| Constant | 0.0811 | |

| (0.0556) | ||

| Year | YES | YES |

| City | YES | YES |

| N | 3519 | 3519 |

| R2 | 0.8548 | 0.0688 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Correction of EWP Outliers | Control the Fixed Effects of Provinces | Control Fixed Effects of Provinces and Cities | Control the Fixed Effects of the Interaction Between Provinces and Years |

| DID | 0.0111 ** | 0.0265 *** | 0.0133 *** | 0.0346 *** |

| (0.0043) | (0.0057) | (0.0051) | (0.0087) | |

| People | 0.0066 | 0.0048 *** | 0.0044 ** | 0.0043 ** |

| (0.0053) | (0.0017) | (0.0021) | (0.0021) | |

| Urban | −0.0003 ** | −0.0003 *** | −0.0004 ** | −0.0003 ** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |

| Fisdecentra | 0.0094 ** | 0.0067 * | 0.0112 *** | 0.0080 |

| (0.0041) | (0.0035) | (0.0030) | (0.0050) | |

| Number | −0.0020 * | −0.0003 | −0.0005 ** | −0.0013 |

| (0.0012) | (0.0003) | (0.0002) | (0.0014) | |

| Export | 0.0019 | 0.0005 | 0.0011 * | 0.0001 |

| (0.0027) | (0.0010) | (0.0006) | (0.0031) | |

| Passenger | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 *** | −0.0000 |

| (0.0013) | (0.0002) | (0.0001) | (0.0003) | |

| Primary | −0.0409 | 0.0494 * | −0.0426 | 0.0575 * |

| (0.0340) | (0.0254) | (0.0323) | (0.0297) | |

| Tec | 0.0000 | −0.0010 | 0.0007 | −0.0023 |

| (0.0016) | (0.0015) | (0.0012) | (0.0017) | |

| Revenue | 0.0007 * | 0.0005 | 0.0007** | 0.0008 |

| (0.0004) | (0.0004) | (0.0003) | (0.0006) | |

| Constant | 0.0455 *** | 0.0393 *** | 0.0465 *** | 0.0372 *** |

| (0.0104) | (0.0072) | (0.0062) | (0.0090) | |

| City | YES | NO | YES | NO |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Province | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Province×Year | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| N | 3519 | 3519 | 3519 | 3434 |

| R2 | 0.7537 | 0.4277 | 0.7423 | 0.4704 |

| (1) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | EWP | EWP | EWP |

| DID | 0.0133 *** | 0.0133 *** | 0.0133 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | |

| DID01 | 0.0006 | 0.0007 | |

| (0.0060) | (0.0060) | ||

| DID02 | −0.0009 | −0.0009 | |

| (0.0046) | (0.0046) | ||

| People | 0.0044 ** | 0.0044 ** | 0.0044 ** |

| (0.0021) | (0.0021) | (0.0021) | |

| Urban | −0.0004 ** | −0.0004 ** | −0.0004 ** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |

| Fisdecentra | 0.0112 *** | 0.0112 *** | 0.0112 *** |

| (0.0030) | (0.0030) | (0.0030) | |

| Number | −0.0005 ** | −0.0005 ** | −0.0005 ** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | |

| Export | 0.0011 * | 0.0010 | 0.0010 |

| (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | |

| Passenger | 0.0006 *** | 0.0006 *** | 0.0006 *** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |

| Primary | −0.0426 | −0.0428 | −0.0428 |

| (0.0322) | (0.0321) | (0.0321) | |

| Tec | 0.0007 | 0.0007 | 0.0007 |

| (0.0012) | (0.0012) | (0.0012) | |

| Revenue | 0.0007 ** | 0.0007 ** | 0.0007 ** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | |

| Constant | 0.0465 *** | 0.0465 *** | 0.0465 *** |

| (0.0062) | (0.0062) | (0.0062) | |

| City | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 3519 | 3519 | 3519 |

| R2 | 0.7423 | 0.7423 | 0.7423 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EWP | EWP | EWP | EWP | |

| DID | 0.0133 *** | 0.0149 *** | 0.0133 *** | 0.0137 *** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0050) | (0.0051) | (0.0051) | |

| Regu | 0.9098 * | |||

| (0.5004) | ||||

| DID × Regu | 5.0218 *** | |||

| (1.7573) | ||||

| Labor | 0.0025 | |||

| (0.0016) | ||||

| DID × Labor | −0.0146 *** | |||

| (0.0044) | ||||

| People | 0.0044 ** | 0.0046 ** | 0.0044 ** | 0.0045 ** |

| (0.0021) | (0.0021) | (0.0021) | (0.0021) | |

| Urban | −0.0004 ** | −0.0004 *** | −0.0004 ** | −0.0004 ** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |

| Fisdecentra | 0.0112 *** | 0.0108 *** | 0.0112 *** | 0.0108 *** |

| (0.0030) | (0.0031) | (0.0030) | (0.0030) | |

| Number | −0.0005 ** | −0.0006 *** | −0.0005 ** | −0.0005 ** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | |

| Export | 0.0011 * | 0.0012 * | 0.0011 * | 0.0011 * |

| (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | (0.0006) | |

| Passenger | 0.0006 *** | 0.0006 *** | 0.0006 *** | 0.0006 *** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |

| Primary | −0.0426 | −0.0560 * | −0.0426 | −0.0421 |

| (0.0321) | (0.0327) | (0.0321) | (0.0316) | |

| Tec | 0.0007 | 0.0010 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 |

| (0.0012) | (0.0011) | (0.0012) | (0.0012) | |

| Revenue | 0.0007 ** | 0.0007 ** | 0.0007 ** | 0.0007 ** |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | |

| Constant | 0.0465 *** | 0.0464 *** | 0.0465 *** | 0.0454 *** |

| (0.0062) | (0.0062) | (0.0062) | (0.0062) | |

| City | Yes | Yes | YES | YES |

| Year | Yes | Yes | YES | YES |

| N | 3519 | 3519 | 3519 | 3519 |

| R2 | 0.7423 | 0.7442 | 0.7423 | 0.7440 |

| Explained Variable: EWP | High Air Pollution | Low Air Pollution | Old Industrial Base Cities | Non-Old Industrial Base Cities | Big City | Small City |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| DID | 0.0197 *** | 0.0087 | 0.0287 *** | 0.0099 * | 0.0238 *** | 0.0054 |

| (0.0052) | (0.0072) | (0.0102) | (0.0060) | (0.0080) | (0.0064) | |

| People | 0.0066 ** | 0.0039 * | −0.0040 | 0.0036 | −0.0062 | 0.0048 ** |

| (0.0026) | (0.0021) | (0.0066) | (0.0026) | (0.0115) | (0.0019) | |

| Urban | −0.0006 *** | −0.0003 ** | −0.0005 | −0.0003 * | 0.0006 | −0.0004 *** |

| (0.0002) | (0.0001) | (0.0003) | (0.0002) | (0.0009) | (0.0001) | |

| Fisdecentra | 0.0133 *** | 0.0114 *** | 0.0191 ** | 0.0099 *** | 0.0095 ** | 0.0105 * |

| (0.0048) | (0.0030) | (0.0077) | (0.0034) | (0.0042) | (0.0061) | |

| Number | −0.0024 ** | −0.0008 *** | 0.0016 | −0.0006 *** | −0.0004 * | 0.0001 |

| (0.0010) | (0.0003) | (0.0032) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0023) | |

| Export | 0.0009 | 0.0017 *** | −0.0208 | 0.0011 * | 0.0013 | −0.0222 * |

| (0.0026) | (0.0005) | (0.0139) | (0.0006) | (0.0008) | (0.0115) | |

| Passenger | 0.0005 *** | 0.0006 *** | −0.0016 | 0.0006 *** | 0.0005 *** | 0.0005 |

| (0.0002) | (0.0001) | (0.0033) | (0.0001) | (0.0002) | (0.0020) | |

| Primary | −0.0560 * | −0.0121 | −0.0464 | −0.0419 | −0.0356 | −0.0351 |

| (0.0326) | (0.0512) | (0.0434) | (0.0455) | (0.1057) | (0.0320) | |

| Tec | −0.0006 | 0.0025 ** | −0.0007 | 0.0012 | 0.0003 | 0.0009 |

| (0.0014) | (0.0013) | (0.0037) | (0.0012) | (0.0014) | (0.0024) | |

| Revenue | 0.0010 ** | 0.0004 | 0.0011 *** | 0.0006 | −0.0001 | 0.0014 ** |

| (0.0004) | (0.0003) | (0.0004) | (0.0004) | (0.0004) | (0.0005) | |

| Constant | 0.0510 *** | 0.0425 *** | 0.0589 *** | 0.0479 *** | 0.0407 | 0.0507 *** |

| (0.0075) | (0.0085) | (0.0181) | (0.0078) | (0.0280) | (0.0081) | |

| Test for difference in coefficients between groups | 0.0050 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | |||

| City | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1400 | 2119 | 1258 | 2261 | 945 | 2570 |

| R2 | 0.7601 | 0.7753 | 0.7382 | 0.7469 | 0.7514 | 0.7299 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, X. Environmental Regulation and Urban Ecological Welfare Performance in China: Evidence from the Key Cities for Air Pollution Control Policy. Sustainability 2026, 18, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010284

Zhu L, Wang Y, Yuan R, Zhang X. Environmental Regulation and Urban Ecological Welfare Performance in China: Evidence from the Key Cities for Air Pollution Control Policy. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010284

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Lingrui, Yihan Wang, Run Yuan, and Xinyue Zhang. 2026. "Environmental Regulation and Urban Ecological Welfare Performance in China: Evidence from the Key Cities for Air Pollution Control Policy" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010284

APA StyleZhu, L., Wang, Y., Yuan, R., & Zhang, X. (2026). Environmental Regulation and Urban Ecological Welfare Performance in China: Evidence from the Key Cities for Air Pollution Control Policy. Sustainability, 18(1), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010284