Institutions, Globalization and the Dynamics of Opportunity-Driven Innovative Entrepreneurship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Fundamental Indicators over Time

3.1.1. Trends in ODE over Time

3.1.2. Trends in MI over Time

3.1.3. Trends in EF over Time

3.1.4. Trends in Governance over Time

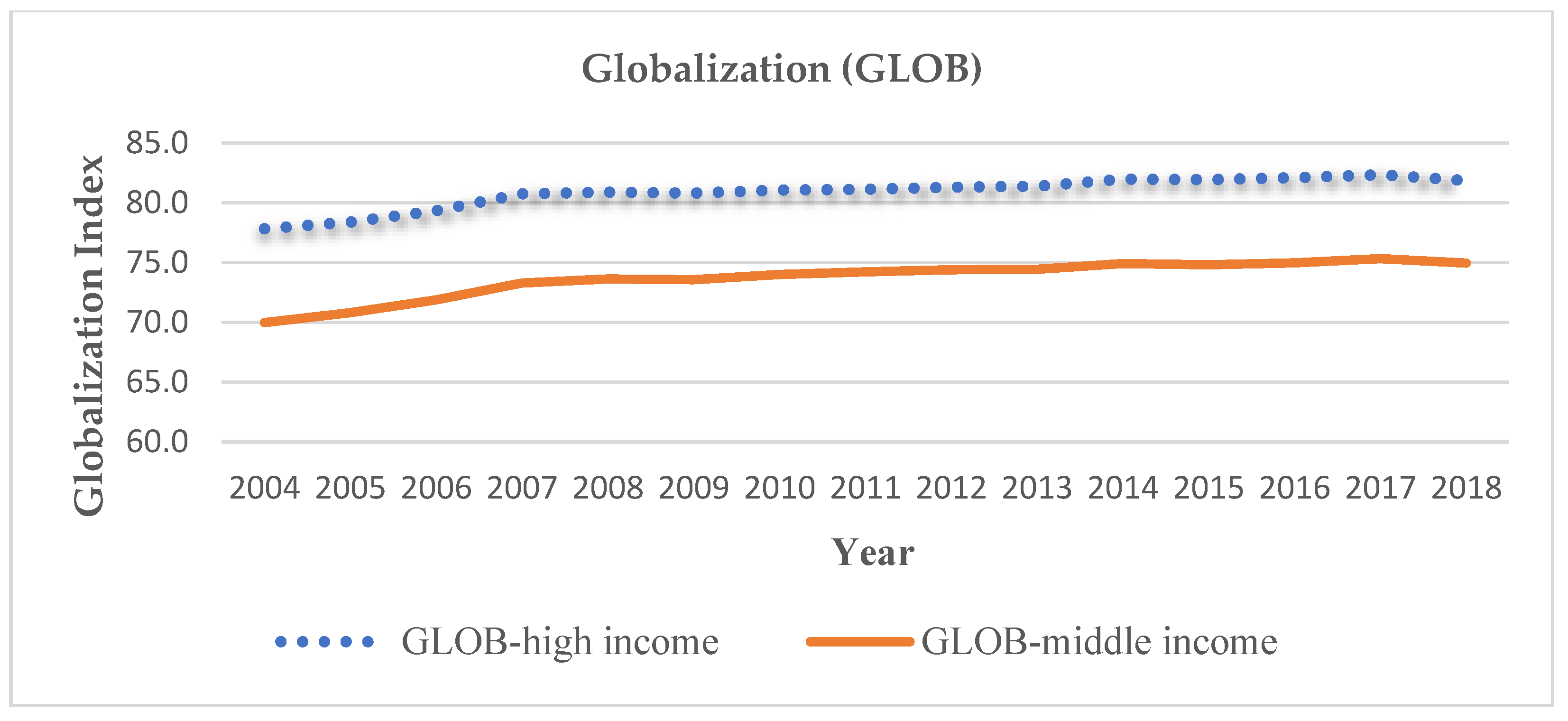

3.1.5. Trends in Globalization over Time

3.2. Summary of Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Economic Freedom

4.2. Governance

4.3. Globalization

4.4. Insights for Policy Makers

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ODE | Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship |

| NDE | Necessity-driven entrepreneurship |

| MI | Motivational Index |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| TEA | Total early-stage entrepreneurial activity |

| OECD | Organization for economic cooperation and development |

| GMM | Generalize methods of moments |

| APS | Adult population of survey |

| GEM | Global entrepreneurship monitor |

| EF | Economic freedom |

| GOV | Governance |

| GLOB | Globalization |

| R_D | Government expenditure on research and development as a percentage of GDP |

| H | Hypothesis |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| UD | US dollars |

| WDI | World development indicators |

| RLS | Robust least squares |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

Appendix A

| Variable | Description/Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunity-Driven Entrepreneurship (ODE) | Percentage of individuals those who involved in TEA who claim to be driven by opportunity, and who state that their primary motivation is seizing an opportunity and cite independence or income growth as the main driving force. | Global Entrepreneurship Monitor |

| Motivational Index (MI) | Percentage of those involved in TEA that are improvement-driven opportunity motivated, divided by the percentage of TEA that is necessity-motivated | Global Entrepreneurship Monitor |

| Economic Freedom Index (EF) | Consists of ten elements categorized into four main groups: rule of Law; limited government; regulatory efficiency; and open markets. A score of 100 signifies the highest level of economic freedom. (scale 0–100) | The Global Economy.com |

| Governance Index (GOV) | A composite index of six governance indices (control of corruption, government effectiveness, political stability and absence of violence, regulatory quality, rule of law, voice and accountability) | World Bank |

| Globalization Index (GLOB) | The overall index of globalization encompasses the economic, social, and political aspects of globalization. Higher scores indicate a higher degree of globalization. (scale 0–100) | The Global Economy.com |

| Gross Enrolment ratio for Tertiary Education (TRT_EDU) | The ratio of total enrollment, irrespective of age, to the population within the age group that corresponds to the indicated level of education. Tertiary education, which may include advanced research qualifications, typically necessitates, at the very least, the successful completion of secondary education for admission. | World Bank |

| Research and Development Expenditure (R_D) | Gross domestic expenditure on research and development (R&D), presented as a percentage of GDP, encompasses both capital and current expenditures across the four primary sectors: business enterprise, government, higher education, and private non-profit. R&D covers applied research, basic research, and development of experiment | World Bank |

Appendix B

- Australia

- Austria

- Barbados

- Belgium

- Canada

- Chile

- Croatia

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Latvia

- Luxembourg

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Panama

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- Uruguay

- U.S.A.

- Angola

- Argentina

- Bosnia

- Brazil

- China

- Colombia

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- Gautama

- India

- Indonesia

- Iraq

- Jamaica

- Kazakhstan

- Lebanon

- Malaysia

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Pakistan

- Peru

- Russia

- South Africa

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

References

- Sagar, S. Entrepreneurship: Catalyst for Innovation and Economic Growth. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A.; Opie, R.; Swedberg, R. The Theory of Economic Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers, S.; Thurik, R. Linking Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Small Bus. Econ. 1999, 13, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W. Growth, Industrial Organization and Economic Generalities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhovskaya, O.R.; Alexandrova, E.A. Motivational Index of Entrepreneurial Activity and the Institutional Environment. Vestnik St. Petersb. Univ. Econ. 2018, 34, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Carlsson, B. Growth and Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2011, 39, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H.; Sternberg, R. The Changing Face of Entrepreneurship in Germany. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 28, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Kohn, K.; Miller, D.; Ullrich, K. Necessity Entrepreneurship and Competitive Strategy. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 44, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Guerrero, M.J.; Pérez-Moreno, S.; Abad-Guerrero, I.M. How Economic Freedom Affects Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurship in the OECD Countries. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 73, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, C.J.; Caudill, S.B. Entrepreneurship, Institutions, and Economic Growth: Does the Level of Development Matter? In MPRA Paper No. 94244; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B. Political Institutions: An Overview. In New Handbook of Political Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, F. Institutions and Economic, Political, and Civil Liberty in the Arab World; Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2022; Available online: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/research/institutions-and-economic-political-and-civil-liberty-arab-world (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Chowdhury, F.; Desai, S. Necessity or Opportunity? Government Size, Tax Policy, Corruption, and Implications for Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 58, 2025–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N.J. Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity: Some cross-country evidence. Public Choice 2007, 134, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Bagby, D.R.; Palich, L.E. Economic freedom and the motivation to engage in entrepreneurial action. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Casero, J.C.; Almodóvar González, M.; de la Cruz Sánchez Escobedo, M.; Coduras Martínez, A.; Hernández Mogollón, R. Institutional variables, entrepreneurial activity, and economic development. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.C.; Mpeqa, A. The more the merrier? Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena-Martín, E.; Medina-Claros, S.; Pérez-Moreno, S. Economic regulation, opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and gender gap: Emerging versus high-income economies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentelsaz, L.; González, C.; Maícas, J.P.; Montero, J. How different formal institutions affect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2015, 18, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D.; Audretsch, D. Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 102, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentelsaz, L.; González, C.; Maicas, J.P. Formal institutions and opportunity entrepreneurship: The contingent role of informal institutions. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2019, 22, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghih, N.; Bonyadi, E.; Sarreshtehdari, L. Entrepreneurial Motivation Index: Importance of Dark Data. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2021, 11, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaei Kordshouli, H.; Maleki, B. Entrepreneurship Motivation and Institutions: System Dynamics and Scenario Planning. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2023, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, S.; O’Brien, S.; Kok, S.; Gallagher, E. Entrepreneurial Motivations, Opportunities, and Challenges: An International Perspective. J. Afr. Bus. 2020, 23, 380–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwartney, J.; Lawson, R.; Hall, J. Economic Freedom of the World: 2016 Annual Report; The Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016. Available online: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/economic-freedom-of-the-world-2016.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Vinig, T.G.; de Kluijver, J. Does globalization impact entrepreneurship? Comparative study of country-level indicators. Sprouts Work. Pap. Inf. Syst. 2008, 7, 194. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all/194/ (accessed on 17 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, T. How does institutional quality affect business start-up in high- and middle-income countries? An international comparative study. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 14, 2830–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, C.J.; Nikolaev, B. Capital is not enough: Opportunity entrepreneurship and formal institutions. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 53, 709–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós, J.E. The impact of institutions on entrepreneurship in developing countries. In Entrepreneurship and Economic Development; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011; pp. 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, L.A.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A. To formalize or not to formalize: Entrepreneurship and pro-market institutions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, C.J.; Nikolaev, B.; Klein, P. Socio-Cognitive Traits and Entrepreneurship: The Moderating Role of Economic Institutions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, A.R.; Verheul, I.; Hessels, J. Factors Influencing the Entrepreneurial Engagement of Opportunity and Necessity Entrepreneurs. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2016, 6, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidis, R.; Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T. Institutions and Entrepreneurship Development in Russia: A Comparative Perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Desai, S.; Hessels, J. Entrepreneurship, Economic Development and Institutions. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, M.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Small vs. young firms across the world: Contribution to employment, job creation, and growth. In Policy Research Working Papers; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savrul, M. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth: GEM data analysis. Pressacademia 2017, 4, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Rietveld, C.A. Does globalization affect perceptions about entrepreneurship? The role of economic development. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 58, 1545–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoa-Gyarteng, K.; Dhliwayo, S. The role of globalization in entrepreneurial development and unemployment: A comparative study of South Africa and the United Kingdom. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2025, 67, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Definitions; GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A. Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2023 Update; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: www.govindicators.org (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Jiménez, A.; Palmero-Cámara, C.; González-Santos, M.J.; González-Bernal, J.; Jiménez-Eguizábal, J.A. The impact of educational levels on formal and informal entrepreneurship. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2015, 18, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassicieh, S.S. The knowledge economy and entrepreneurial activities in technology-based economic development. J. Knowl. Econ. 2010, 1, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, L.; Grim, C.; Zolas, N. A portrait of U.S. firms that invest in R&D. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2019, 29, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSIAO, C. Why panel data? Singap. Econ. Rev. 2005, 50, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadeh, N.; Rompaey, C.V.; Metreau, E.; Eapen, S.G. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2022–2023. World Bank Blogs, 1 July 2022. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023 (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Doner, R.F.; Schneider, B.R. The middle-income trap. World Polit. 2016, 68, 608–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentor, J. The long-term effects of globalization on income inequality, population growth, and economic development. Soc. Probl. 2001, 48, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.; Storper, M. Regions, Globalization, Development. Reg. Stud. 2003, 37, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| High-Income Countries | Middle-Income Countries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ODE | EF | GOV | GLOB | ODE | EF | GOV | GLOB | |

| Mean | 6.1225 | 69.0954 | 2.7429 | 82.1416 | 8.9593 | 58.1987 | −0.8544 | 65.6700 |

| Median | 5.0657 | 69.0000 | 2.6947 | 82.7900 | 8.1233 | 58.0000 | −0.7355 | 65.1100 |

| Maximum | 21.7261 | 83.0000 | 5.0120 | 91.3100 | 26.9211 | 72.0000 | 1.2716 | 80.9400 |

| Minimum | 1.1079 | 52.0000 | −1.1573 | 65.8900 | 1.9156 | 40.0000 | −3.1371 | 51.3100 |

| Std. Dev. | 3.1724 | 6.6648 | 1.3881 | 5.6998 | 4.8738 | 7.2443 | 0.8662 | 5.7145 |

| Skewness | 1.6852 | −0.1590 | −0.2706 | −0.4490 | 0.8203 | −0.2124 | −0.2836 | 0.1312 |

| Kurtosis | 6.6107 | 2.3923 | 2.1712 | 2.4456 | 3.4795 | 2.4226 | 3.3310 | 3.7233 |

| Jarque-Bera | 330.3794 | 6.3696 | 13.2678 | 15.0828 | 18.3822 | 3.2329 | 2.7139 | 3.7250 |

| Probability | 0.0000 | 0.0414 | 0.0013 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.1986 | 0.2574 | 0.1553 |

| Sum | 1989.82 | 22,456.00 | 891.45 | 26,696.03 | 1352.86 | 8788.00 | −129.02 | 9916.17 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 3260.67 | 14,392.04 | 624.28 | 10,525.93 | 3563.13 | 7872.03 | 112.55 | 4898.35 |

| Observations | 325 | 325 | 325 | 325 | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 |

| High-Income Countries | Middle-Income Countries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI | EF | GOV | GLOB | MI | EF | GOV | GLOB | |

| Mean | 3.5593 | 70.3511 | 2.7660 | 82.2861 | 1.8282 | 58.1463 | −0.9076 | 65.3130 |

| Median | 2.8200 | 70.0000 | 3.0125 | 82.9400 | 1.3900 | 58.0000 | −0.7529 | 65.1600 |

| Maximum | 19.5000 | 89.0000 | 4.8214 | 91.3100 | 9.2200 | 74.0000 | 1.2716 | 81.4100 |

| Minimum | 0.6200 | 53.0000 | −1.1573 | 63.1800 | 0.3500 | 38.0000 | −3.1150 | 42.8100 |

| Std. Dev. | 2.7324 | 6.8598 | 1.4158 | 6.1816 | 1.3589 | 7.9910 | 0.9346 | 6.8355 |

| Skewness | 2.2053 | 0.0369 | −0.5348 | −0.8589 | 2.3720 | −0.2280 | −0.2360 | −0.6561 |

| Kurtosis | 9.8650 | 2.5997 | 2.4429 | 3.5390 | 10.5456 | 2.2307 | 2.7476 | 4.7022 |

| Jarque-Bera | 726.8565 | 1.8088 | 15.8774 | 35.3848 | 542.8588 | 5.4713 | 1.9570 | 31.5662 |

| Probability | 0.0000 | 0.0448 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0648 | 0.3759 | 0.0000 |

| Sum | 932.5500 | 18,432.0 | 724.6943 | 21,558.95 | 299.8300 | 9536 | −148.8555 | 10,711.34 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 1948.678 | 12,281.69 | 523.1916 | 9973.40 | 300.9944 | 10,408.49 | 142.3760 | 7616.1230 |

| Observations | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 | 164 | 164 | 164 | 164 |

| Variable | ODE | EF | GOV | GLOB | R_D | TRT_EDU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Income | ||||||

| ODE | 1.0000 | |||||

| EF | 0.3830 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| GOV | 0.0139 | 0.7183 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| GLOB | −0.2541 *** | 0.4168 *** | 0.7030 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| R_D | −0.2107 *** | 0.3501 *** | 0.5971 *** | 0.5117 *** | 1.0000 | |

| TRT_EDU | 0.0406 | 0.0019 | 0.1288 *** | 0.1615 *** | 0.1817 *** | 1.0000 |

| Middle Income | ||||||

| ODE | 1.0000 | |||||

| EF | 0.2716 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| GOV | 0.0206 | 0.5531 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| GLOB | −0.1900 ** | 0.4513 *** | 0.6080 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| R_D | −0.1941 ** | −0.2302 *** | 0.1156 | 0.1658 ** | 1.0000 | |

| TRT_EDU | −0.0285 | −0.3185 *** | −0.0999 | 0.1603 ** | 0.0667 | 1.0000 |

| Variable | MI | EF | GOV | GLOB | R_D | TRT_EDU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Income | ||||||

| MI | 1.0000 | |||||

| EF | 0.3761 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| GOV | 0.5641 *** | 0.71448 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| GLOB | 0.3811 *** | 0.3767 *** | 0.7170 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| R_D | 0.4353 *** | 0.3897 *** | 0.7138 *** | 0.6876 *** | 1.0000 | |

| TRT_EDU | 0.0437 | −0.0854 | −0.0137 | 0.0570 | 0.1711 | 1.0000 |

| Middle Income | ||||||

| MI | 1.0000 | |||||

| EF | 0.5048 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| GOV | 0.4218 | 0.5152 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| GLOB | 0.4905 *** | 0.4538 *** | 0.5775 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| R_D | −0.0044 | −0.2214 * | 0.1503 | 0.1848 * | 1.0000 | |

| TRT_EDU | 0.1006 | −0.3193 | −0.0975 | 0.1013 ** | 0.1093 | 1.0000 |

| High Income | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | |

| EF | 0.1670 *** | 0.2517 *** | ||||

| GOV | 0.3604 *** | 0.4909 *** | ||||

| GLOB | −0.0828 *** | −0.1152 *** | ||||

| R_D | −0.8680 *** | −1.2746 *** | −0.7186 *** | −1.0794 *** | −0.0771 | −0.3739 * |

| TRT_EDU | 0.0098 | 0.0221 ** | −0.0047 | 0.0148 | −0.0037 | 0.0184 * |

| Constant | −5.1557 *** | −10.6626 *** | 5.9251 *** | 5.5613 *** | 12.6703 *** | 14.9372 *** |

| Observations | 325 | 325 | 325 | 325 | 325 | 325 |

| Number of cross sections | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Middle Income | ||||||

| RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | |

| EF | 0.1664 ** | 0.1749 *** | ||||

| GOV | 0.1702 | 0.2382 | ||||

| GLOB | −0.1467 ** | −0.1395 ** | ||||

| R_D | −0.1874 | −1.3433 * | −0.6868 ** | −1.9231 ** | −1.3595 * | −1.6252 ** |

| TRT_EDU | 0.0167 | 0.0153 | −0.0018 | 0.0027 | 0.0014 | 0.0021 |

| Constant | −0.9431 | −1.0187 | 9.9392 *** | 10.5143 | 19.0261 *** | 19.0751 *** |

| Observations | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 | 151 |

| Number of cross sections | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| High Income | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | |

| EF | 0.0925 *** | 0.1096 *** | ||||

| GOV | 0.6259 *** | 1.0483 *** | ||||

| GLOB | 0.0287 | 0.0778 * | ||||

| R_D | 0.6978 *** | 0.9828 *** | 0.2984 ** | 0.1479 | 0.8642 *** | 0.9693 *** |

| TRT_EDU | −0.0017 | 0.0010 | −0.0004 | 0.0065 | −0.0078 | −0.0034 |

| Constant | −4.6600 *** | −5.8069 *** | 0.7208 * | −0.0267 | −0.3939 | −4.2929 |

| Observations | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 |

| Number of cross sections | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| Middle Income | ||||||

| RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | RLS | OLS | |

| EF | 0.0776 *** | 0.1095 *** | ||||

| GOV | 0.3346 *** | 0.7078 *** | ||||

| GLOB | 0.0653 *** | 0.1219 *** | ||||

| R_D | 0.0571 | 0.2588 | −0.1853 | −0.2274 | −0.1685 | −0.2661 |

| TRT_EDU | 0.0164 *** | 0.0190 *** | 0.0057 | 0.0102 | 0.0029 | 0.0040 |

| Constant | −3.6869 *** | −5.5903 *** | 1.5724 *** | 2.1045 *** | −2.7956 * | −6.2217 *** |

| Observations | 114 | 114 | 114 | 114 | 114 | 114 |

| Number of cross sections | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wickramasinghe Koralage, N.N.K.; Li, W.; Cooray, S. Institutions, Globalization and the Dynamics of Opportunity-Driven Innovative Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2026, 18, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010252

Wickramasinghe Koralage NNK, Li W, Cooray S. Institutions, Globalization and the Dynamics of Opportunity-Driven Innovative Entrepreneurship. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010252

Chicago/Turabian StyleWickramasinghe Koralage, Nirupa N. K., Wenkai Li, and Seneviratne Cooray. 2026. "Institutions, Globalization and the Dynamics of Opportunity-Driven Innovative Entrepreneurship" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010252

APA StyleWickramasinghe Koralage, N. N. K., Li, W., & Cooray, S. (2026). Institutions, Globalization and the Dynamics of Opportunity-Driven Innovative Entrepreneurship. Sustainability, 18(1), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010252