1. Introduction

The accelerated evolution of digital technologies has been continually reshaping social and productive structures, redefining how individuals, organizations, and governments engage with the world. This ongoing transformation reflects not only the incorporation of new tools but also the emergence of new ethical, cultural, and environmental demands that challenge society to rethink its forms of interaction and development. The dynamics of change affect communication, labor, and essential sectors such as health, education, and governance. This rapid evolution, however, brings considerable challenges, requiring constant adaptation, regulation of new tools, protection of data privacy and security, and sustained debate on the ethical and social issues that arise [

1].

It is precisely within this field of debate that one of the most profound transformations is occurring with the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI stands out as one of the most revolutionary technologies. Its applications are vast, altering production processes and decision-making across multiple sectors. AI affects not only the economy but also society and the environment, influencing the human–machine relationship and underscoring the need for transparent algorithms, the mitigation of biases in learning models, and sound data governance [

2].

Artificial Intelligence is being integrated into an increasingly complex ecosystem of emerging technologies, such as Big Data, the Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, cloud computing, quantum computing, and immersive technologies, including Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality. This convergence exponentially expands application possibilities and fosters innovative solutions to contemporary challenges in the economic, social, and environmental spheres. More than merely complementing technological resources, the integration across these fronts is redefining the very nature of innovation, making it more connected, predictive, and impact-oriented toward sustainability.

From the perspective of social and environmental challenges, the climate crisis and its associated impacts spur the search for technological solutions that optimize resources and promote sustainable practices, aligning economic development with environmental and social needs. Nevertheless, the use of AI raises concerns such as the widening of technological inequality across countries and sectors, increased energy consumption for data processing, and the risk of bias and discrimination [

3].

In this context, it is crucial to adopt a Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HCAI) approach that is developed based on ethical principles, inclusion, transparency, and positive impact. In this way, Artificial Intelligence not only improves efficiency, but also respects human rights, reduces inequalities, and creates opportunities for the well-being of all. This perspective makes it possible to analyze how Artificial Intelligence can drive Sustainable Development without compromising social aspects, ensuring that its application is guided by the real needs of society and by essential human values.

In this article, HCAI is understood as an approach that guides the design, governance, and evaluation of Artificial Intelligence systems based on the primacy of human and socio-environmental values, rather than solely on technical performance metrics. HCAI implies placing human agency and oversight, participatory solution design, bias mitigation, and the active protection of vulnerable groups at the center of the technology’s life cycle. This involves articulating, in an integrated way, the technical dimension (reliability, robustness, and explainability of models), the ethical dimension (justice, transparency, accountability, and protection of rights), and the socio-environmental dimension (effective contribution to Sustainable Development and prevention of adverse impacts). From this perspective, HCAI is not limited to a set of best practices but constitutes an interdisciplinary framework that guides the very formulation of problems, the choice of data, methods, and success criteria for Artificial Intelligence applications, in order to align technological innovation, social justice, and sustainability.

The rapid expansion of Artificial Intelligence heralds a transformation capable of redefining economic, educational, environmental, and institutional patterns. However, the absence of robust guidelines and systemic understanding of its relationship with Sustainable Development creates a gap that inhibits responsible adoption. Without clear ethical and regulatory frameworks, AI’s transformative potential remains underutilized, when it could serve as a strategic lever to accelerate the Sustainable Development Goals.

Against this backdrop, the central research question emerges: How has research on Human-Centered AI (HCAI) advanced Sustainable Development during the 2020–2024 period?

With the expansion of digital infrastructure—including high-performance cloud computing, sensor networks, and 5G connectivity—a new generation of AI applications has become possible. When guided by the principles of Human-Centered AI, this infrastructure can contribute to achieving SDG targets [

4]. Nonetheless, its implementation also creates social and environmental tensions that must be carefully managed [

3].

Kaufman, Junquilho, and Reis [

5] (p. 63) note that “the future of AI will depend on the efforts of academic and non-academic researchers to address at least part of the current technical limitations, and on society’s gradual awareness of its ethical and social impacts”. This reinforces the need to monitor technological progress to ensure it is guided by principles of social justice, environmental stewardship, and, above all, the promotion of Sustainable Development.

In the environmental–climatic domain, machine learning algorithms fed by satellite series from the Copernicus program, operated by the European Space Agency (ESA), together with local meteorological networks, refine greenhouse gas emission inventories, identify urban heat-island patterns, and anticipate extreme events days in advance, a crucial window for disaster management [

6]. Deep learning models, combined with sensor networks along transmission lines, optimize the distribution of renewable energy, reducing losses and integrating intermittent sources. These examples relate to SDGs 7 and 13 [

7].

In food production, the convergence of onboard computer vision in drones, multispectral imagery from the Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellites (both operated by ESA), and in situ sensors (weather stations and soil-moisture probes) enables algorithms to detect water stress, nutrient deficiencies, and pest infestations with centimeter-level precision [

8]. Precision agriculture trials using variable-rate nitrogen application in wheat—guided by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which compares reflectance in red and near-infrared bands to estimate canopy vigor—derived from Sentinel-2 recorded an average 22% reduction in nitrogen input and improved nitrogen-use efficiency without yield loss, outcomes that translate into lower environmental and economic costs and align directly with SDGs 2 and 12 [

9].

Public health has also benefited from AI. Convolutional neural networks—models inspired by the organization of the visual cortex and specialized in recognizing complex patterns in images—applied to radiology can identify subtle signs of early-stage lung tumors [

10], while algorithms based on natural language processing scan online records for signals of emerging outbreaks, anticipating epidemiological alerts [

11,

12]. These advances contribute to SDG 3.

In urban contexts, the materialization of resilient cities and infrastructures manifests across multiple technological fronts. Intelligent traffic systems based on reinforcement learning algorithms adjust traffic signal timing in real time and can reduce CO

2 emissions by approximately 16% [

13]. In parallel, dynamic routing models for solid-waste collection demonstrate fuel savings near 20% and operating-cost reductions of about 19% [

14]. Complementarily, AI-driven building energy optimization platforms report up to 25% reductions in energy consumption in Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems, which account for a substantial share of total building energy demand, and up to 40% reductions in associated emissions [

15]. Taken together, these technological innovations advance SDGs 11 and 9 by reinforcing urban resilience and sustainability.

AI has also become an ally of biodiversity conservation. Automated classifiers process millions of camera-trap images, identifying species in seconds, a task that previously required months of manual work [

16]. In addition, detection models based on synthetic aperture radar (SAR), a remote sensing technology that uses microwaves to generate imagery even through clouds and forest canopy, can identify illegal deforestation under cloud cover, triggering enforcement almost in real time [

17]. These advances reinforce SDGs 13, 14, and 15.

To systematically assess how AI interacts with the various SDG targets, Vinuesa et al. [

3] conducted an expert elicitation process cross-referencing 169 targets across the 17 SDGs with evidence from real-world applications, laboratory studies, international reports, and documented commercial cases. They found that benefits are most pronounced for environmental targets (93%) and less so for economic ones (70%), while risks concentrate mainly in the social dimension (38%).

Building on Vinuesa et al. (2020) [

3], it is possible to conclude that AI tends to catalyze progress on a large share of the SDGs, especially in energy efficiency, resource management, and productive innovation, while simultaneously revealing structural vulnerabilities associated with socioeconomic inequalities, algorithmic bias, and high energy demand. In the Social dimension, gains in education, health, and basic services contrast with risks of widening income disparities and discrimination. In the Economic dimension, productivity increases coexist with income shifts from labor to capital and technological concentration. Finally, in the Environmental sphere, advances in climate monitoring and conservation may be offset by the intensive energy consumption of AI systems.

Accordingly, this research aims to analyze how the scientific production on Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence has contributed to advancing Sustainable Development between 2020 and 2024, identifying its evolution, major themes, collaboration networks, and most influential authors.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Selected Sample

The study was conducted using two internationally recognized databases: Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. Searches on both platforms were carried out in February 2025.

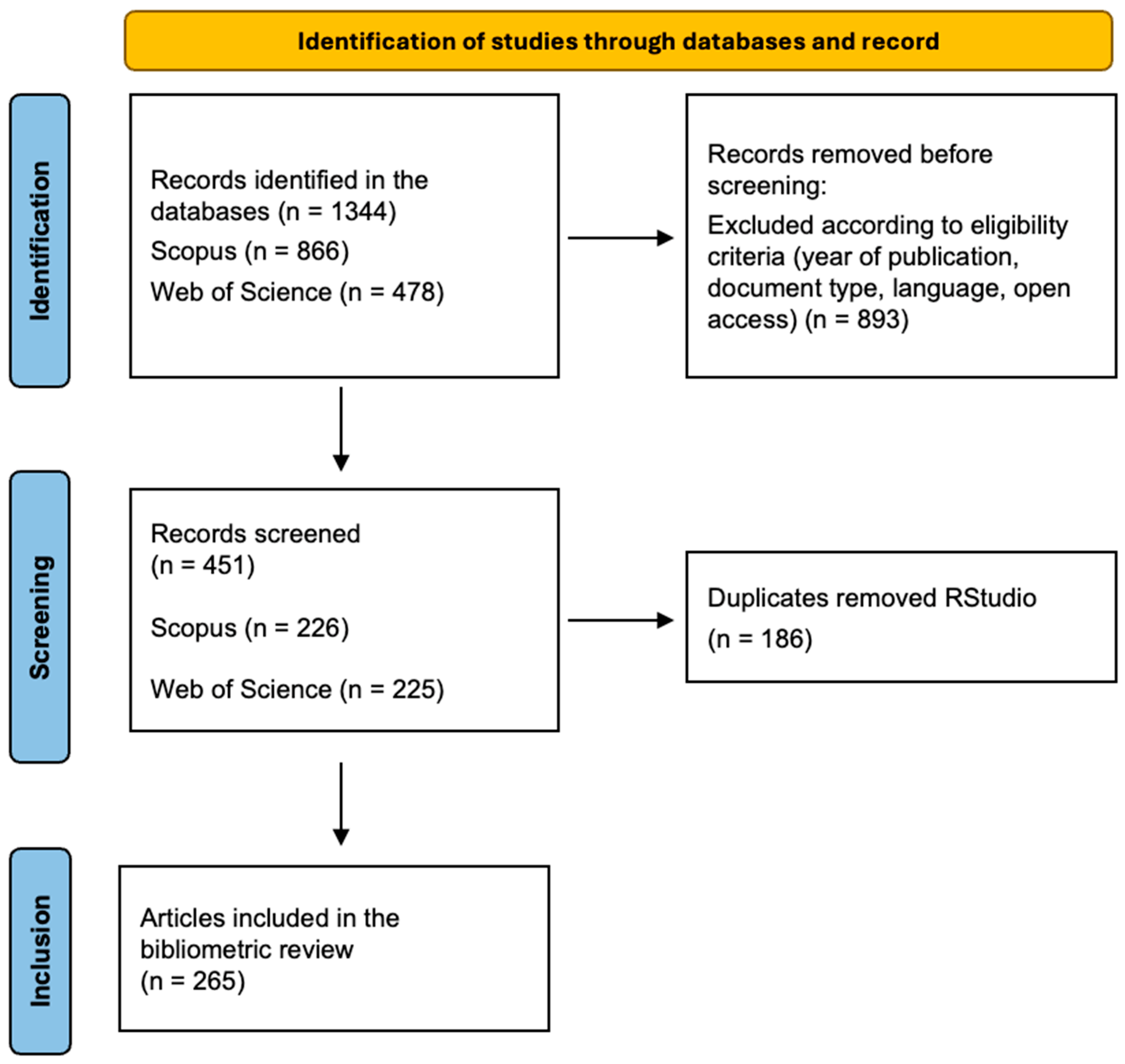

The refinement of results proceeded in three successive stages to ensure the thematic relevance of the studies to the research objectives (

Table 1).

The initial stage of the search returned a substantial volume of documents in both databases analyzed. In Scopus, 25,552 records were identified, while Web of Science yielded 12,648 documents. After applying an additional set of descriptors to improve thematic relevance, the results were significantly reduced to 866 documents in Scopus and 478 in WoS. This stage underscored the importance of rigorous screening to ensure the pertinence of the studies selected. The final refinement process included restrictions by publication year (2020 to 2024), document type (articles and review articles), publication stage (final), language (English), and access type (all open access), resulting in the final selection of 226 documents in Scopus and 225 in WoS to compose the corpus for the bibliometric analysis as show in

Figure 1. This methodological rigor helps ensure that the analyzed data align with the research objectives and reflect the current state of scientific production on Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development.

The delimitation of the publication period 2020 to 2024 stems from the scarcity of earlier studies: only 10 articles are indexed in Scopus and 2 in WoS using the same search operators as this study in an exploratory search extending the time frame to before 2019.

The results indicate that there was already a body of work that articulated Artificial Intelligence, human centeredness, and concerns with Sustainable Development. In the field of natural resources, Couto et al. [

25] apply AI tools to water quality modeling, making explicit their relevance to a human-centered sustainable development process. In the energy field, Hertig and Teufel [

26] discuss the cooperative behavior of prosumers and advocate more human-centric community arrangements to enable the transition to decentralized energy systems, while Sonetti, Naboni, and Brown [

27] and Casado-Mansilla et al. [

28] explore the use of ICT, IoT, and AI in the design of sustainable buildings and cities, with an emphasis on energy efficiency and on the relationship between users and the built environment. Schraefel et al. [

29] anticipate challenges of meaningful consent and privacy in ubiquitous IoT ecosystems. More recent works, such as Moghadami and Kharrat [

30] and Bethke [

31], propose, respectively, an “Internet of Human” framework for health business models and an agenda of components for AI for social good projects. Therefore, these contributions prior to 2019 show that elements of HCAI and its interface with Sustainable Development were already present in sectoral studies and in proposals for conceptual framing, even though the explicit consolidation of HCAI as an integrated approach intensifies only in the more recent years mapped in this article.

The initial set of documents retrieved from Scopus and Web of Science totaled 451 records. The next step consisted of removing duplicates, a process carried out with the aid of the Bibliometrix library in the RStudio environment. A total of 186 duplicate records were identified and unified into a single comma-separated values (CSV) file. This procedure enabled the standardization of metadata extracted from both databases, ensuring that all fields were organized according to the same technical parameters. This harmonization was essential to enable the use of Biblioshiny in the development of subsequent bibliometric analyses.

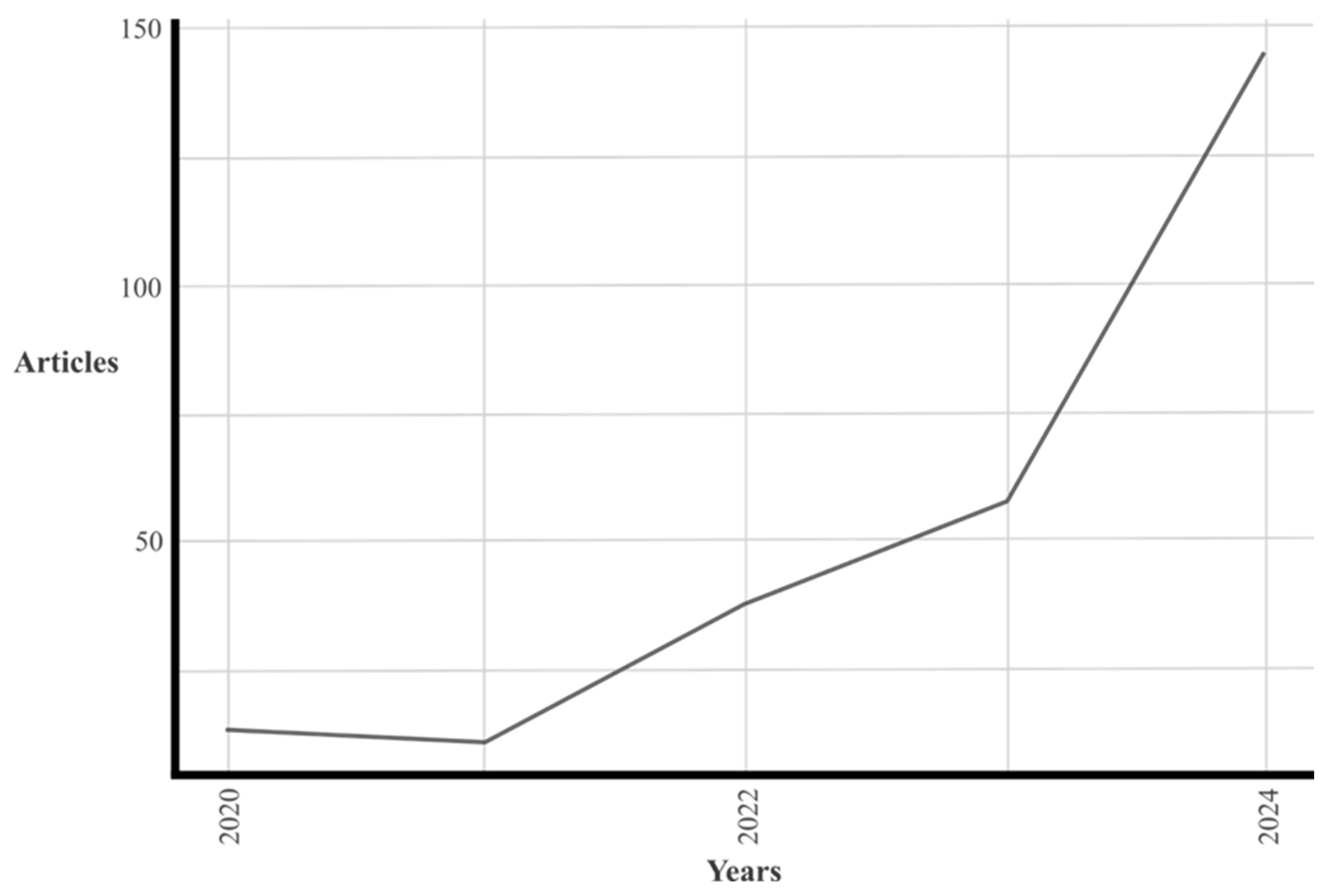

Figure 2 highlights the significant growth of scientific production on the theme of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence at the interface with Sustainable Development in the period 2020 to 2024.

The data in

Figure 2 show a pattern of continuous, accelerated growth, especially from 2022 onward. At the beginning of the series, volumes were still modest, with 13 publications in 2020 and 11 in 2021. A clear inflection point appears in 2022, when the annual total jumped to 38 articles. Growth remained steady in 2023, with 58 publications, and reached its peak in 2024, with 145 documents. In percentage terms, these results represent an increase of over 1000% in five years, signaling the maturation of the research field, rising academic interest, and the consolidation of the topic’s scientific relevance on the international stage.

This marked expansion can be attributed, among other factors, to growing scholarly mobilization around the SDGs, the expansion of computational infrastructure for AI research, and the emergence of ethical and social debates concerning the responsible use of these technologies. These elements reinforce the pertinence of investigating the contribution of Artificial Intelligence from a human-centered perspective, particularly in addressing contemporary global challenges.

Table 2 presents a consolidated view of the document set that comprises the corpus analyzed in this study, obtained through the application of thematic and temporal filters in the Scopus and Web of Science databases.

The total of 265 documents comprises 215 original research articles and 50 review articles, published across 165 different journals, which demonstrates the topic’s interdisciplinary breadth and its dissemination across diverse areas of knowledge.

The annual growth rate of publications was approximately 83 percent, reinforcing the data presented in

Table 2 and evidencing a rapid dynamic of scientific production. The selected documents received an average of 15 citations per publication, totaling more than 3900 accumulated citations, which denotes recognition and significant scientific impact. In addition, the articles collectively reference 19,475 other works, evidencing the field’s bibliographic density and its degree of articulation with other emerging themes.

3.2. Identification of Institutions, Authors, and Scientific Journals

The analyzed documents were produced by 1204 distinct authors, with a notably high rate of scientific collaboration, as only 19 articles were single-authored. It is also noteworthy that approximately 36 percent of the publications resulted from international collaborations involving researchers from different countries, contributing to global knowledge exchange and the strengthening of transnational scientific networks.

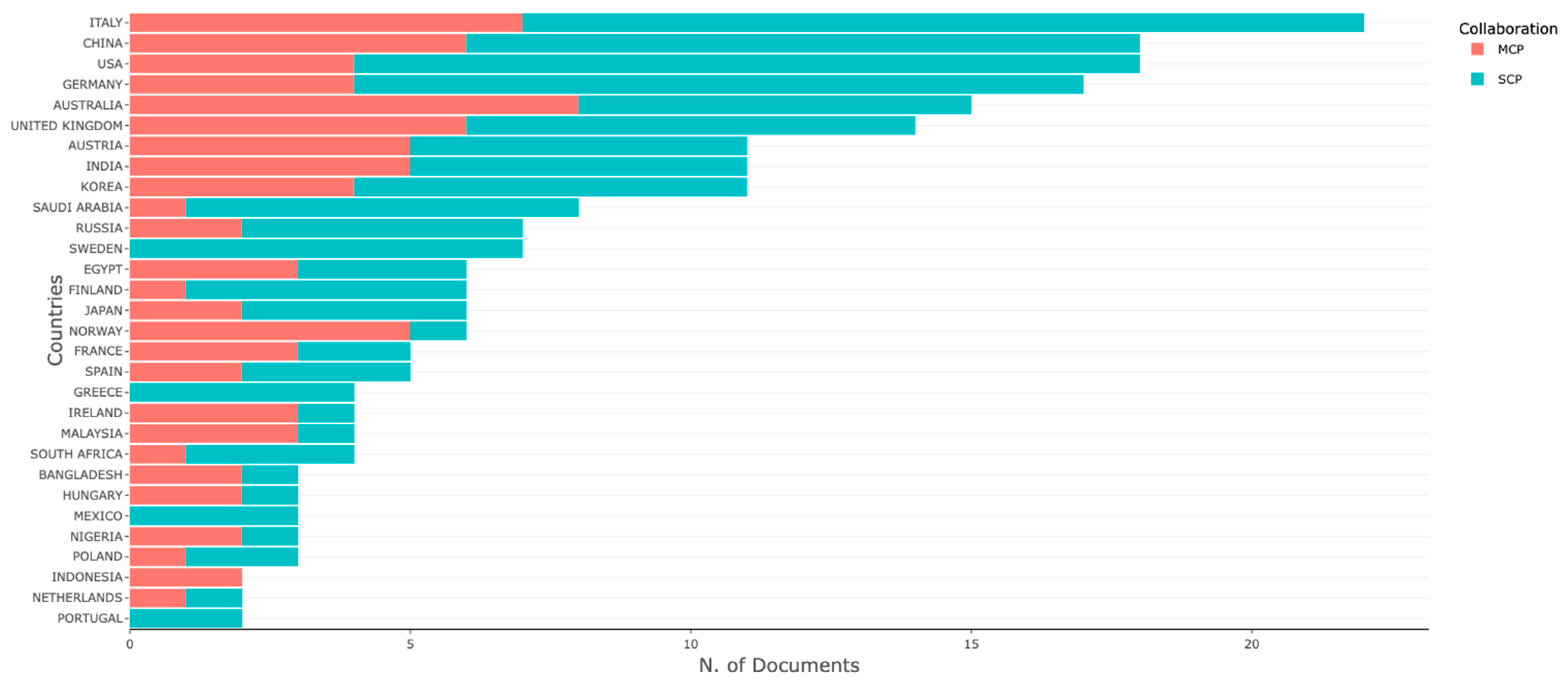

Figure 3 presents an analysis of scientific productivity by country, considering the institutional affiliation of the corresponding author of each publication. The chart in

Figure 3 distinguishes two types of collaboration: Single Country Publications (SCP), produced entirely by authors from a single country, and Multiple Country Publications (MCP), which involve international cooperation among authors of different nationalities. This distinction makes it possible to observe not only the volume of publications by country but also the degree of internationalization of scientific production in the field of Artificial Intelligence applied to Sustainable Development.

Figure 3 shows that, during the period analyzed, the mapped documents were produced by authors affiliated with institutions in 47 countries, underscoring the global nature of research on Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development. The five countries with the largest number of publications were: Italy, with 22 publications (15 SCP and 7 MCP); China, with 18 (12 SCP and 6 MCP); the United States, also with 18 (14 SCP and 4 MCP); Germany, with 17 (13 SCP and 4 MCP); and Australia, with 15 publications, the only country in the group with a predominance of international collaboration (7 SCP and 8 MCP).

The high proportion of MCP in countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and Norway suggests strong integration into international scientific networks. By contrast, the predominance of SCP in countries such as China and the United States may indicate a high capacity for domestic production but also potential barriers to transnational collaboration. Notably, Brazil is absent from the countries with significant output in the analyzed corpus, which may indicate a gap in national scientific insertion on this specific topic or a dispersion of Brazilian authors within multinational networks where they do not appear as corresponding authors.

Beyond providing a view of the geographic distribution of output,

Figure 3 also enables inferences about the collaborative profile of the scientific community. Countries with higher proportions of MCP tend to participate in consortia, bilateral partnerships, or international thematic networks, which contributes to the diversification of perspectives and to increased publication impact.

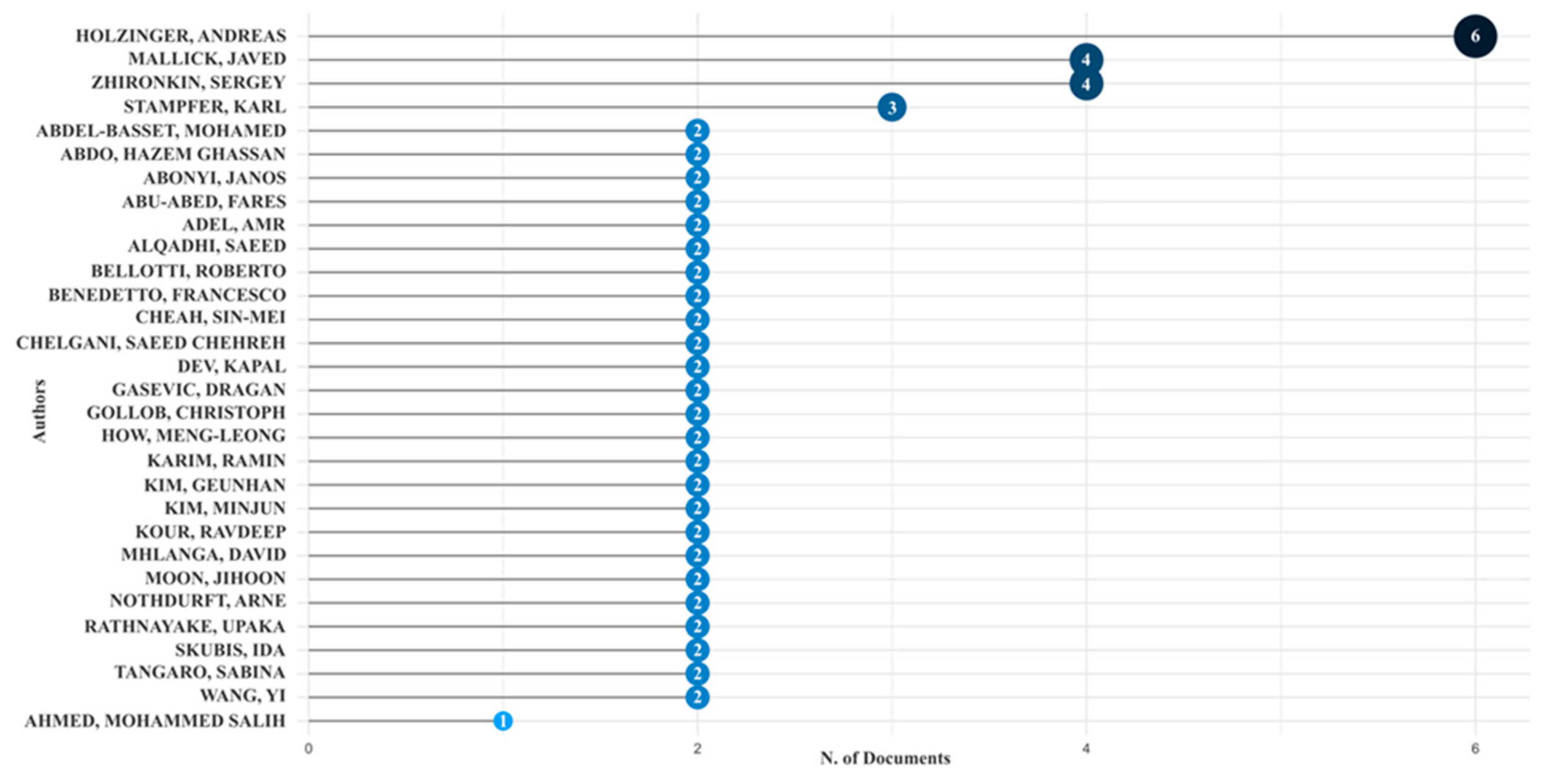

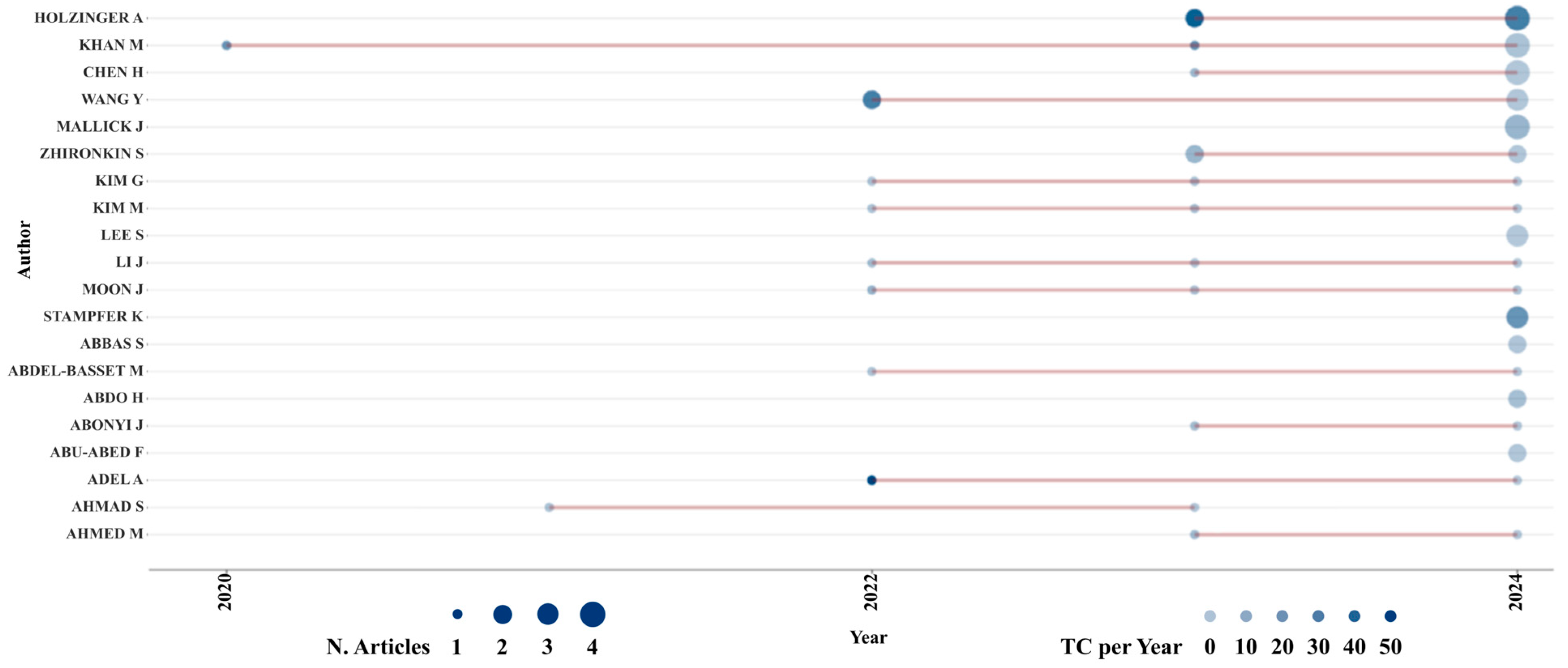

Figure 4 presents the most relevant authors, considering the number of publications identified in the study corpus. The analysis, conducted via Biblioshiny, makes it possible to visualize the researchers with the greatest thematic recurrence. This identification is important for mapping networks of influence, potential centers of excellence, and future references for theoretical, methodological, and applied deepening.

Figure 4 shows that the author Andreas Holzinger leads scientific output, with six publications. He is followed by Javed Mallick and Sergey Zhironkin, with four articles each, and Karl Stampfer, with three. There is also a group of twenty-five authors with two publications each, indicating consistency in their contributions.

Although the numbers may seem modest, the fact that a few authors concentrate multiple publications in an emerging field may indicate thematic specialization and the consolidation of research lines, while also reinforcing the importance of further studies on this topic. It is also worth noting the geographic and institutional diversity of the authors, which may suggest the formation of research hubs distributed globally, reinforcing the interdisciplinary and international nature of the discussion on AI and Sustainable Development.

The discussion of the themes of the articles published by the main authors in the corpus of this research is presented in the following section and covers, among other aspects, the interface between XAI, forestry, agriculture, and health; the principles of Industry 5.0 applied to social dimensions; and the impact of territorial planning and environmental risk management.

Figure 5 presents the evolution of publication volume for the 20 most productive authors in the corpus and the citations received per year for their works. Each line corresponds to an author; the points mark years in which publications occurred. Bubble size represents the number of articles published in the period for a given author (N. Articles), while color intensity indicates the total citations per year (TC per Year) associated with their contributions. This visualization allows productivity and normalized impact over time to be observed simultaneously.

The distribution shows a densification of output from 2022 onward, peaking in 2024, indicating the recency and acceleration of the field within the analyzed period. Heterogeneity between productivity and impact is observed: some authors combine a larger number of articles and high TC per year, forming a core of reference; others, with fewer publications, display relatively high TC per year, suggesting works with high marginal effect.

Figure 5 chart reinforces that the theme has recently been consolidating, with diverse author trajectories and an emerging nucleus of influence.

Table 3 presents the documents with the greatest citation impact in the study corpus; the aim is to characterize citations by author, year of publication, and journal, as well as to compare absolute citation volume (TC) with the intensity of annual citations (TC per Year), allowing the identification of reference works that structure the debate on HCAI applied to Sustainable Development.

The articles in

Table 3 total 1629 citations. The range is substantial, 87 to 393 citations, indicating asymmetry in publication impact. The five most-cited articles account for 68.7% of all citations in the sample. In absolute terms, the leading items are Schwendicke et al. [

32] with 393 citations and 65.5 per year; Adel et al. [

33] with 221 citations and 55.25 per year; Yang et al. [

34] with 208 citations and 41.6 per year; Garibay et al. [

35] with 170 citations and 56.67 per year; and Holzinger et al. [

36] with 128 citations and 42.67 per year.

Schwendicke et al. [

32] have presented a narrative review of Artificial Intelligence in dentistry, synthesizing applications in image-based diagnosis and treatment planning, and discussing limitations, the need for clinical validation, and ethical implications. Adel et al. [

33] develop a conceptual review of Industry 5.0 with a human-centered emphasis, outlining solutions, challenges, and a research agenda with implications for resilience and sustainability. Yang et al. [

34] propose a human-centered AI framework for education, showing how observable data can support inference of latent learning states and discussing design requirements and responsible governance. Garibay et al. [

35], in the Human–Computer Interaction field, discuss design requirements and implications of adopting AI-based systems from a user-experience perspective. Holzinger et al. [

36] map AI trends for biotechnology, emphasizing data challenges, integration with the SDGs, and opportunities for future research.

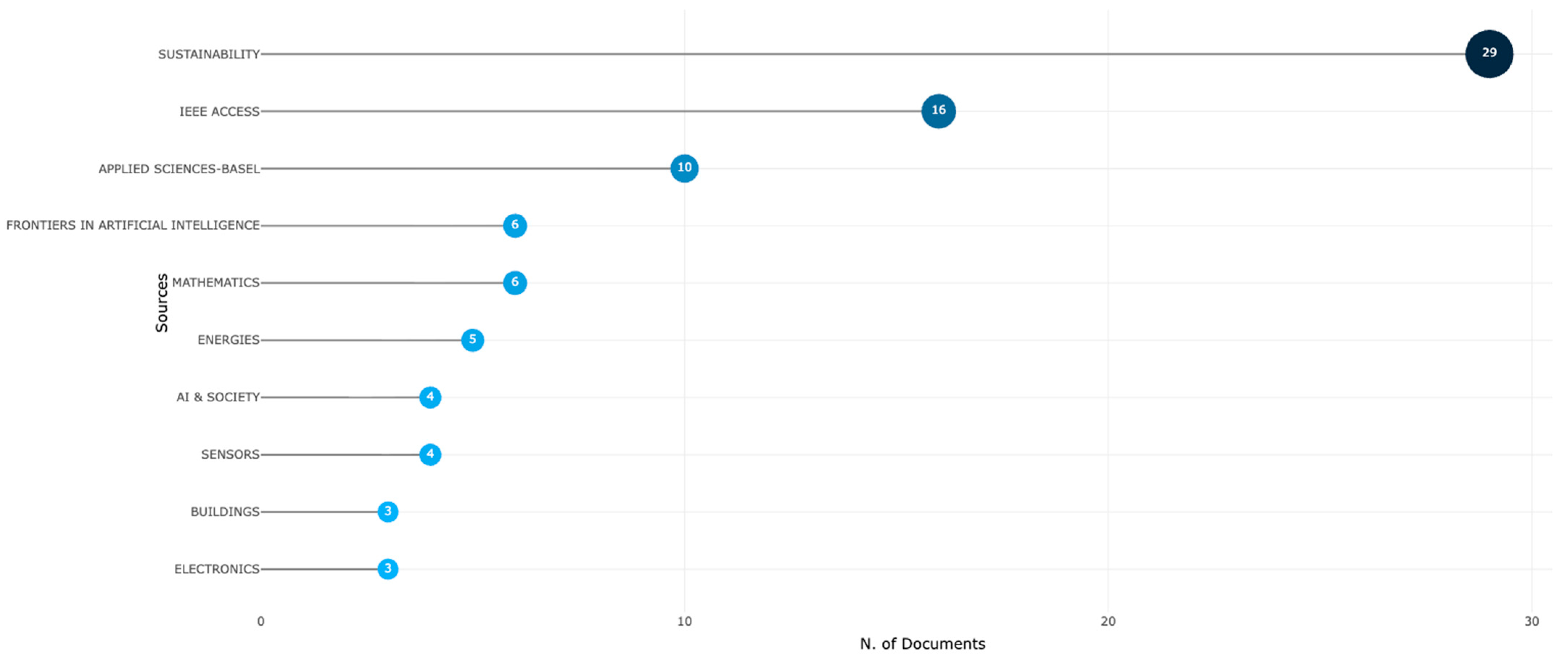

Figure 6 presents the most relevant sources in the corpus, ordered by the number of documents published during the analyzed period. A clear lead is observed for

Sustainability, with 29 articles in the set, followed by

IEEE Access with 16 and

Applied Sciences with 10. The remaining output is distributed across a sequence of journals with lower individual publication volumes.

The predominance of Sustainability is marked and consistent with the study’s focus on Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence applied to Sustainable Development. Relative to the corpus of 265 articles, Sustainability accounts for approximately 10.9% of the total, whereas IEEE Access comprises about 6.0% and Applied Sciences about 3.8%. In terms of the absolute difference, Sustainability publishes 13 more articles than IEEE Access and 19 more than Applied Sciences; in ratio terms, it corresponds to roughly 1.81 times the volume of IEEE Access and 2.9 times that of Applied Sciences. This gradient indicates an editorial venue particularly receptive to intersections between AI and sustainability, alongside engineering- and applied-science outlets that serve as complementary channels. The result suggests that a substantive portion of the debate consolidates in journals with an interdisciplinary scope, with meaningful diffusion toward socio-environmental applications, while maintaining a consistent technical base in engineering and computing venues.

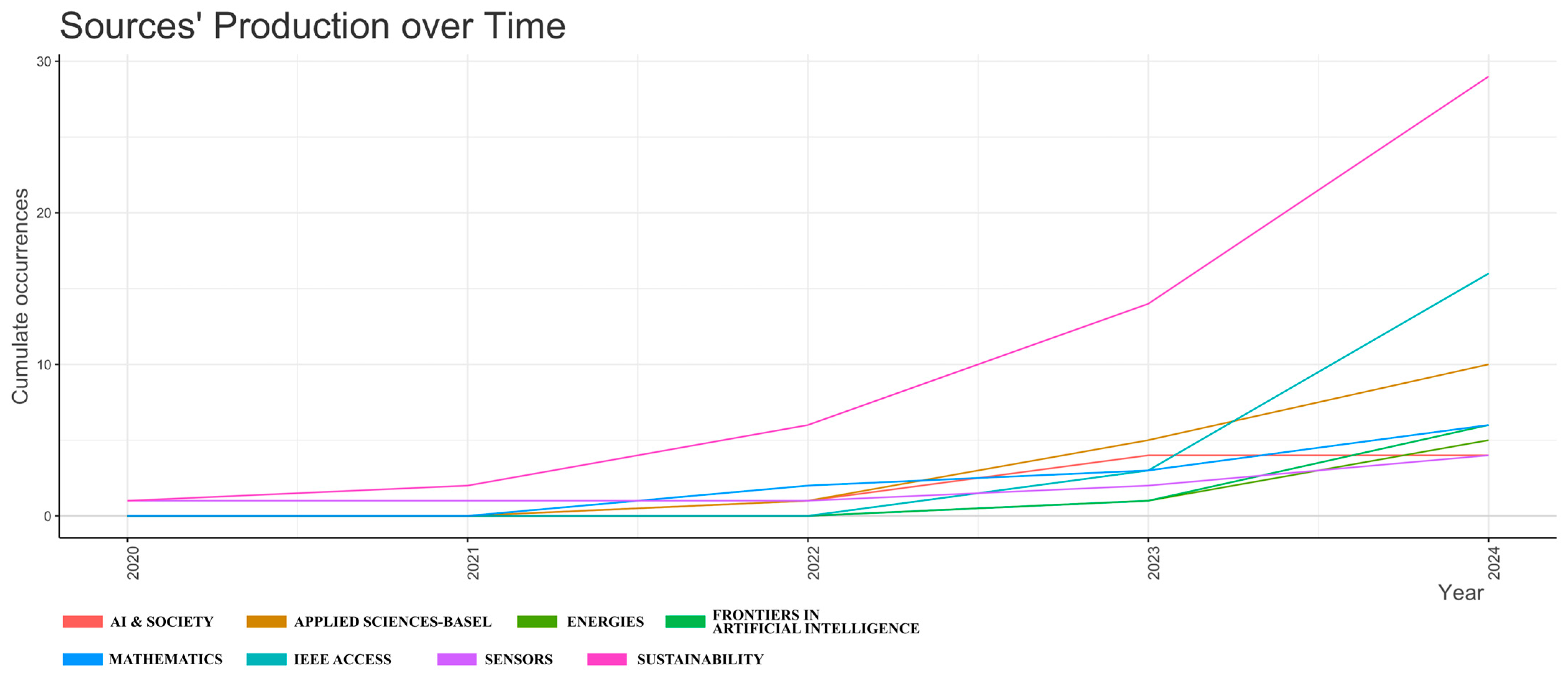

Figure 7 presents the cumulative output by journal between 2020 and 2024. Each line corresponds to a journal, and the value on the vertical axis indicates the cumulative number of articles from that journal in the corpus over time. The chart in

Figure 7 makes it possible to observe not only the final total by journal but especially the growth rate (slope of the curve), highlighting distinct editorial trajectories.

Three patterns are evident. First, Sustainability exhibits a continuous and accelerated trajectory, culminating in 29 publications in 2024; the curve is steepest in 2023–2024, confirming its role as the field’s editorial reference in the period. Second, IEEE Access shows a late takeoff but a marked jump in 2024, ending the period with 16 articles, which represents recent growth and suggests opportunities for applied, engineering-oriented AI studies. Third, Applied Sciences displays stable, near-linear growth, reaching 10 publications in 2024; this behavior indicates a consistent channel for applied research that integrates AI methods with technological problems. The remaining journals maintain incremental dynamics and gentler slopes, reinforcing a concentration pattern in which a few journals account for most of the output. Together with the source ranking, the time series confirms the substantive lead of Sustainability over the other journals and helps explain the recent diffusion of the topic in the analyzed editorial ecosystem.

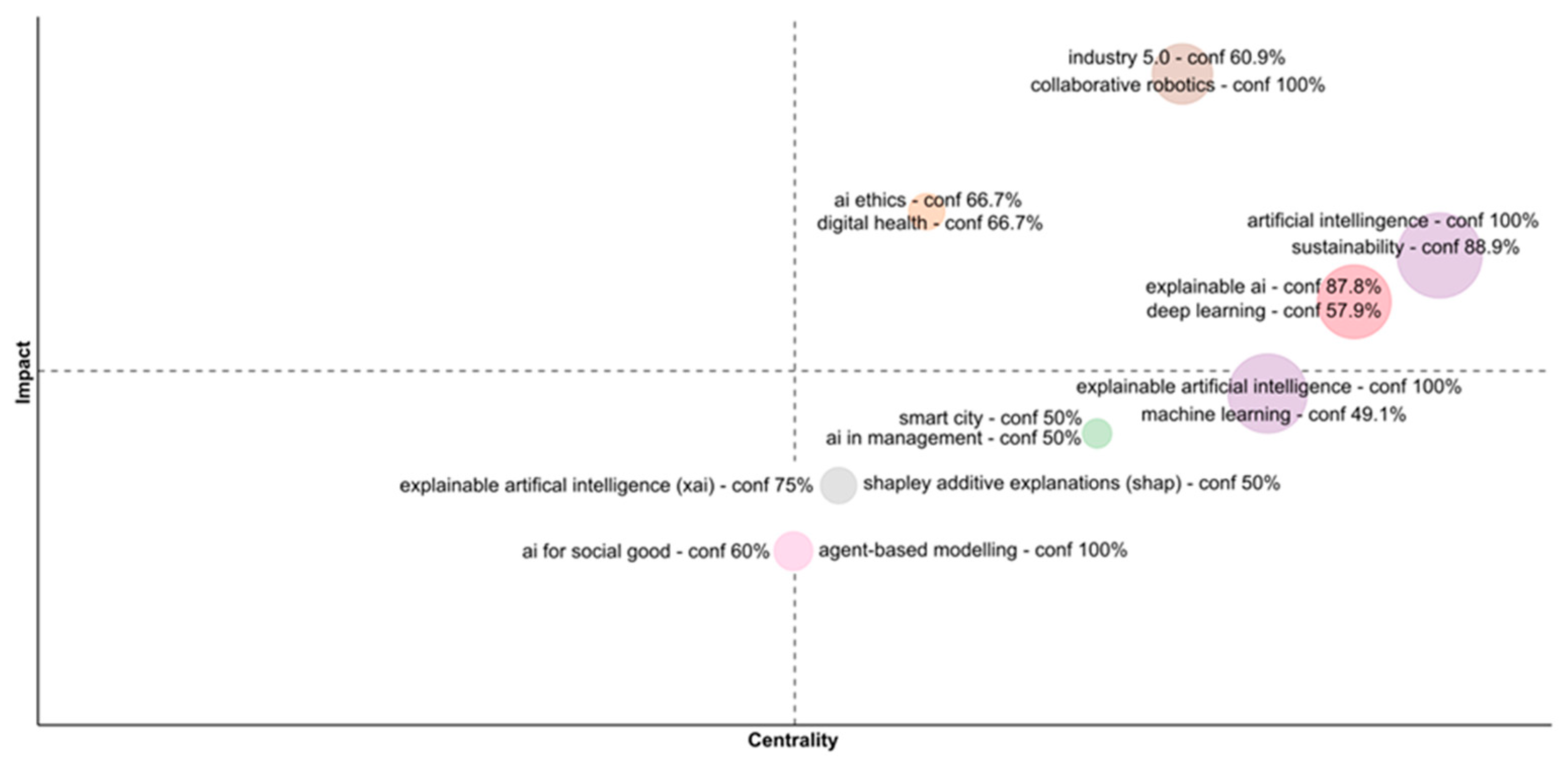

Figure 8 presents themes grouped by bibliographic coupling, that is, by the proximity among items that share references within the corpus. The horizontal axis expresses the centrality of the theme in the network, indicating the extent to which it connects to other groups through common references. The vertical axis represents impact, summarizing citation performance of the set associated with each theme. Bubble size reflects the number of documents linked to the respective label, and the “-%” index indicates the confidence level of the algorithm when generating the clustering. This visualization makes it possible to identify consolidated nuclei, high-impact specializations, and fronts that are still weakly connected, complementing the thematic map by focusing on reference relationships among the works. The processing was carried out with the following parameters: the unit of analysis was Documents, therefore the coupling relationships were computed between documents and not between authors or sources. Coupling was measured based on Author’s Keywords, that is, two documents were considered closer the greater the overlap of their author keywords. The impact of the clusters was evaluated using the Global Citation Score, a metric that sums the global citations of the documents that compose each group. Cluster labeling was generated from Author’s Keywords, so that the labels reflect the most representative terms within each cluster. A total of 250 Units were considered, defining the maximum universe of nodes eligible for analysis. The minimum cluster frequency was set at 10, filtering out very rare communities and increasing the robustness of the groupings. Each cluster received up to two visible labels, and label size was set to 0.3 to improve the readability of the graph. The Community Repulsion parameter was kept at 0, which preserves the default layout of the communities without forcing additional separation among them. The clustering algorithm adopted was Walktrap, which is based on random walks in the network to detect cohesive communities.

A core cluster is observed in the high-centrality, high-impact quadrant, composed of artificial intelligence, sustainability, explainable ai, and deep learning, marked by larger bubbles and high confidence levels. This block indicates that the recent literature combines AI’s technical capability with applications linked to Sustainable Development, supported by a widely shared repertoire of references. To the upper right, Industry 5.0 and collaborative robotics also display high impact and good centrality, suggesting an industrial and organizational trajectory that is highly cited and well-integrated into the main debate. Further to the left, ai ethics and digital health present high impact with moderate centrality, denoting specialized and influential lines that interact with the core but maintain relatively distinct bibliographies. Along the lower band appear labels such as “explainable artificial intelligence” (with variants), “shapley additive explanations”, “ai for social good” and “agent-based modelling” with lower centrality and impact, which may reflect emerging stages or terminological fragmentation.

The Biblioshiny tool has a technical limitation for generating the Bibliographic Coupling (

Figure 8), which may affect the weight and positioning of some keywords: it is not possible to include a thesaurus that merges terms such as “explaniable ai” with “explainable artificial intelligence”. Therefore, the software places in different quadrants keywords that address the same topic, unlike what occurs in

Figure 9, whose processing allows the inclusion of this substitution list.

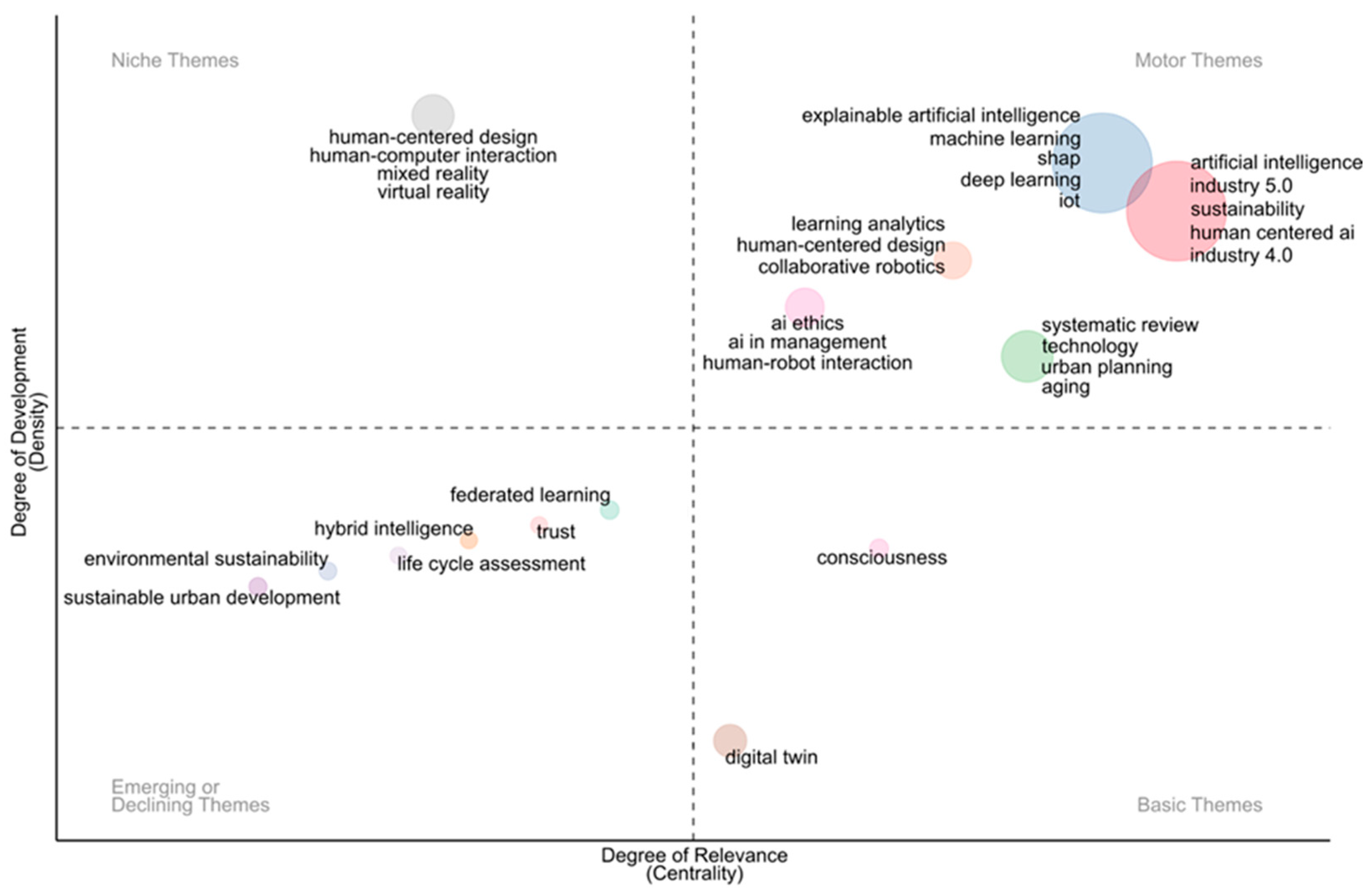

Figure 9 presents the thematic map generated in Biblioshiny from author keywords, in which the horizontal axis represents centrality (the degree of connection of each theme with the others) and the vertical axis represents density (the degree of internal development of the theme). Processing used the following parameters: Avoid label overlap = on; Number of Words = 250; Min Cluster Frequency = 5 (per thousand documents); Number of Labels = 5; Label size = 0.3; Community Repulsion = 0; and the Walktrap clustering algorithm. To reduce terminological noise, a Biblioshiny Thesaurus was applied to unify spelling variants and acronyms—for example, using “explainable artificial intelligence” in place of “explainable AI” and “XAI”, “SHAP” in place of “shapley additive explanations” and normalizing “Industry 4.0/5.0.” This treatment ensures that synonyms do not fragment clusters and improves the interpretability of the map.

Reading of the map reveals two motor poles (high centrality and high density) on the right side of the chart: (i) a methodological block around “explainable artificial intelligence” “machine learning” “deep learning” “SHAP” and “internet of things”; and (ii) a technical–applied block with “artificial intelligence”, “sustainability”, “human-centered AI” and “industry 4.0/5.0” indicating articulation among analytical capacity, governance, and applications in industrial transition and sustainability. In the zone of basic themes (high centrality, lower density) appear “digital twin”, “consciousness”, “aging” and “urban planning” functioning as connectors of the field’s general vocabulary. The emerging/declining quadrant (low centrality and low density) concentrates “environmental sustainability”, “sustainable urban development”, “life cycle assessment”, “trust” and “hybrid intelligence.” These findings suggest topics in early consolidation or specializations that are still weakly integrated with the core. Overall, the map supports a narrative of a field structured by three interdependent layers: technical performance (Machine Learning and Deep Learning); explainability and human-centeredness (XAI and HCAI); and socio-environmental applications, whose evolution follows from the integration of these dimensions.

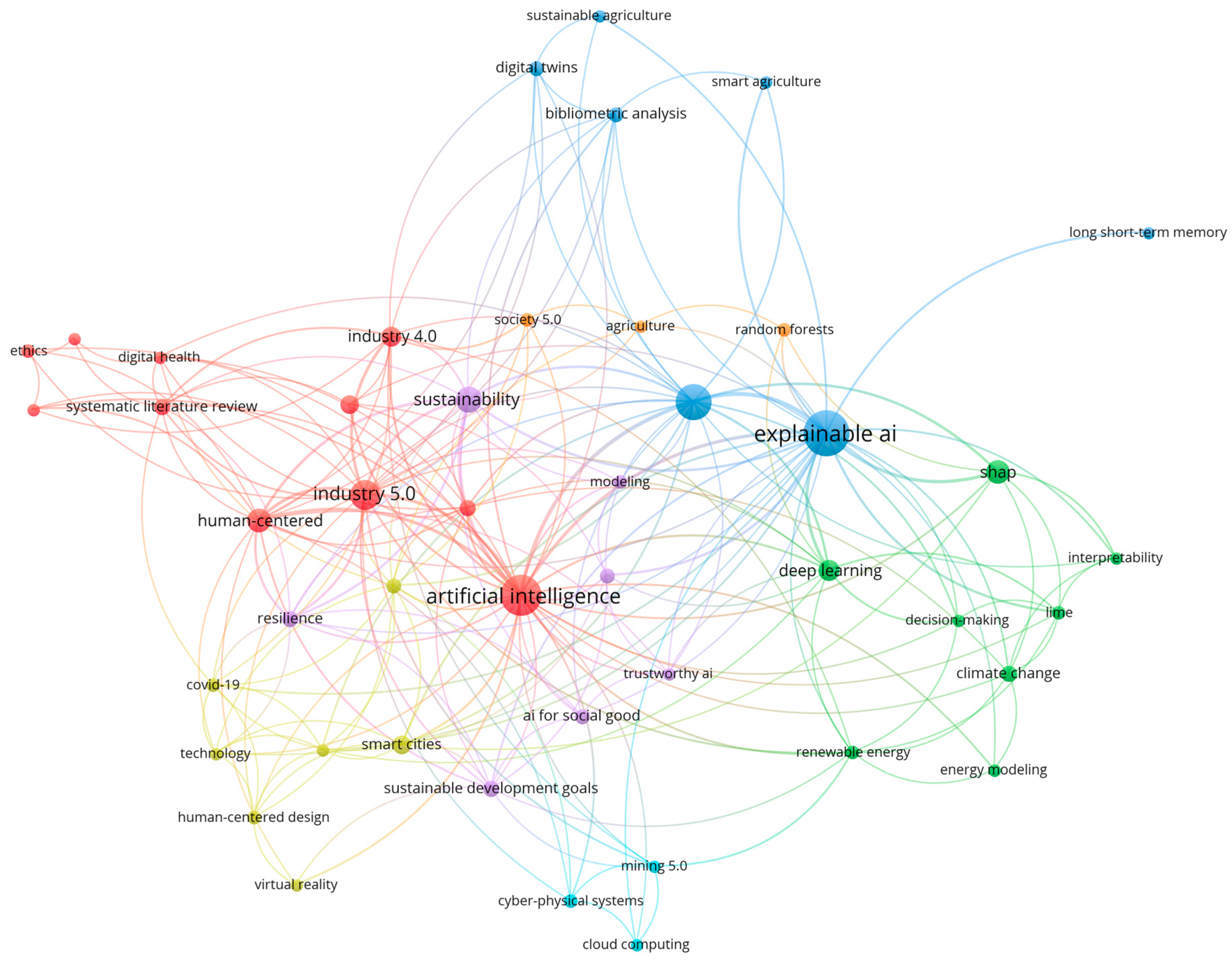

Figure 10 presents the keyword co-occurrence map generated in VOSviewer from bibliographic files exported from Web of Science (.txt format) and Scopus (.csv format), combined in a single run. The analysis type was Co-occurrence, using Author keywords and Full counting; a minimum occurrence of 3 was defined, and VOSviewer selected 46 keywords organized into seven clusters. Sensitivity tests were conducted with different thresholds for the minimum occurrence of keywords. With a minimum of two occurrences, the software identified 100 keywords and 12 thematic clusters; with five occurrences, 20 keywords and 4 clusters; and with ten occurrences, 9 keywords and 3 clusters. The threshold of three occurrences was therefore adopted, as it represents a more balanced compromise between the 5 matic granularity and map readability, avoiding both excessive fragmentation and an overly drastic reduction in the number of clusters. In all tested scenarios, however, the central positioning of the main clusters associated with Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Industry 5.0 remained stable. To mitigate terminological noise, a Thesaurus file in .csv format was applied to unify acronyms, normalize orthographic and singular/plural variations (e.g., AI replacing artificial intelligence; human-centered AI replacing human-centered AI; IoT replacing Internet of Things; SHAP replacing Shapley additive explanations). This preprocessing ensures that synonyms do not spread across distinct nodes and improves structural interpretability.

Figure 10 reveals an architecture organized into interdependent poles, focusing on the most prominent nodes: “artificial intelligence,” “explainable AI,” “machine learning,” “sustainability,” “human-centered AI,” “sustainable development goals,” and “industry 5.0.” A coherent design emerges across technical capability, governance, human-centeredness, and socio-environmental purpose. The keyword “artificial intelligence” acts as the map’s general hub, connecting intensely to “sustainability,” “industry 4.0/5.0,” “human-centered AI,” and application terms such as “smart cities” and “urban planning,” indicating that the discourse on AI in the corpus is predominantly oriented toward Sustainable Development problems and organizational transformation. “Explainable AI,” together with “machine learning” and “deep learning,” forms the methodological core; links to “interpretability,” “LIME,” and “SHAP” suggest the effective adoption of explainability techniques as a requirement for responsible applications. “Machine learning” functions as the analytical backbone, radiating into domains such as “digital twins,” “energy modeling,” and “agriculture/smart agriculture,” which reinforces its cross-cutting role as methodological infrastructure. “Sustainability” appears as a transversal application node, anchoring connections with “renewable energy,” “climate change,” “resilience,” and responsibility-oriented initiatives such as “AI for social good” and “trustworthy AI,” projecting AI toward environmental and social issues. “Human-centered AI” brings the technical layer closer to ethical and design dimensions, such as “AI ethics,” “human-centered design,” and “human-robot interaction,” signaling concern with usability, accountability, and impacts on people and organizations.

The term “sustainable development goals” functions as a normative and impact-measurement marker, linking to “sustainable AI,” “sustainable development,” and sectoral axes such as “smart cities” and “renewable energy,” which evidence alignment with public policies and global metrics. Finally, “industry 5.0” organizes the techno-organizational strand of the map, articulating “industry 4.0,” “cyber-physical systems,” “cloud computing,” “mining 5.0,” and “digital transformation,” a pathway that connects automation and human–machine collaboration to sustainability objectives and corporate resilience. The data in

Figure 10 suggest the consolidation of analytical effectiveness and explainability mechanisms toward human-centeredness and applications oriented to Sustainable Development, lending thematic coherence to this research and reinforcing the topic’s importance and emergence.

What follows are the seven clusters identified by VOSviewer, named according to their predominant themes and accompanied by their respective sets of keywords:

Cluster 1: Governance and AI-driven digital transformation: ai ethics; artificial intelligence; collaboration; digital health; digital transformation; ethics; human-centered; human-centered AI; Industry 4.0; Industry 5.0; systematic literature review.

Cluster 2: Explainability and climate–energy modeling: climate change; decision-making; deep learning; energy modeling; interpretability; LIME; renewable energy; SHAP.

Cluster 3: XAI/ML with digital twins and agriculture: bibliometric analysis; digital twins; explainable AI; long short-term memory; machine learning; smart agriculture; sustainable agriculture.

Cluster 4: Smart cities, IoT, and urban planning: COVID-19; human-centered design; internet of things; smart cities; technology; urban planning; virtual reality.

Cluster 5: Sustainability, resilience, and the normative agenda: AI for social good; modeling; resilience; sustainability; sustainable AI; sustainable development; trustworthy AI.

Cluster 6: Infrastructure and industrial systems: cloud computing; cyber-physical systems; mining 5.0.

Cluster 7: Agriculture, ML methods, and Society: agriculture; random forests; society 5.0.

The cluster analysis enabled the identification of the structure and thematic fronts that constitute the field of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence at its interface with Sustainable Development. These groupings reveal the coexistence of consolidated cores focused on explainability, sustainability, and Industry 5.0, alongside emerging strands still taking shape, such as algorithmic ethics, digital agriculture, and hybrid intelligence models. Building on these results, the next section deepens the discussion of the practical and theoretical implications of these findings, highlighting concrete examples of AI applications in socio-environmental contexts and the challenges that remain for consolidating a research agenda oriented toward the Sustainable Development Goals.

4. Discussion

In the literature, there are numerous concrete examples of Artificial Intelligence applications in contexts oriented toward Sustainable Development. These cases illustrate how AI has been used to confront real-world challenges and to support policies, processes, and technological solutions aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The selection presented in this section seeks to render the advances identified in the bibliometric analysis more tangible, showing how applied research has been materializing the principles of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence across social, economic, and environmental domains, as summarized in

Table 4.

The Google Flood Forecast Initiative is emblematic. Since 2018, the platform has integrated Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks—a class of recurrent networks capable of learning long-range dependencies in time series—together with convolutional neural networks, real-time assimilation of hydrologic data, and flood models to issue flood alerts. During the 2021 monsoon season, the platform sent 115 million notifications to 23 million people, covering an area inhabited by more than 360 million residents in India and Bangladesh [

37]. Owing to modeling advances announced in 2024, the system was expanded to more than 100 countries and now provides forecasts to roughly 700 million people worldwide [

38].

This initiative directly relates to targets 11.5 and 11.b of SDG 11. By converting hydro-meteorological data into short-term, georeferenced alerts, the solution improves the anticipatory and response capacities of civil defense authorities and municipal managers, which tends to reduce deaths, the number of people affected, and economic losses associated with disasters, with emphasis on hydrological events—the core of target 11.5. The public availability of forecasts and risk maps also supports the adoption of integrated disaster risk management and climate adaptation policies and plans in line with the Sendai Framework, a central element of target 11.b, strengthening evacuation protocols, prioritization of critical infrastructure, calibration of sirens, and inclusive communication channels for vulnerable populations in flood-prone areas.

When incorporated into urban planning, these forecasts provide evidence-based inputs for land-use, zoning, and drainage decisions, reinforcing the sustainable urbanization called for by target 11.3 of SDG 11. Effective gains in urban resilience, however, depend on data governance, model transparency, and digital inclusion, in order to mitigate coverage gaps and ensure equitable access to risk information.

Energy efficiency has been another fertile field for AI. Since 2018, DeepMind has deployed deep reinforcement learning algorithms to control Alphabet’s data-center cooling systems, achieving consistent reductions of around 30% in cooling energy consumption [

39]. Such savings contribute to SDG 7 by making digital infrastructure less carbon-intensive and more economically accessible. The gains obtained through intelligent HVAC control speak directly to target 7.3, which aims to double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency. By lowering thermal loads and optimizing the operation of chillers and cooling towers, the energy intensity per data center decreases, contributing to less energy-intensive digital services.

There are indirect effects on target 7.2 insofar as demand modulation facilitates the integration of variable renewable sources into cooling operations. Lower operating costs may also support target 7.1 by enabling providers to pass efficiencies on as more affordable prices for computing and connectivity, broadening lower-cost access for the population.

In agriculture, the IBM Watson Decision Platform for Agriculture integrates AI, IoT, and climate modeling to support planting, irrigation, and harvest decisions. A 2019 pilot conducted by India’s Ministry of Agriculture in three districts showed that the tool provides village-level weather and soil-moisture forecasts, helping producers make more informed choices about water and production management [

40]. Such initiatives align with food security (SDG 2) and responsible consumption (SDG 12) by enhancing input-use efficiency.

The use of localized weather forecasts, soil-moisture estimates, and AI-assisted agronomic recommendations contributes directly to SDG 2, targets 2.3 and 2.4. By guiding planting calendars, irrigation, and integrated pest management, the tool can raise productivity and incomes for smallholders and strengthen the resilience of production systems to climate variability and extreme events. The predictive character of recommendations may reduce inter-season variability and protect yields when combined with local technical assistance, storage infrastructure, and rural insurance strategies.

Under SDG 12, the platform relates to targets 12.2 and 12.3 by rationalizing the use of natural resources and reducing losses along the chain. Irrigation scheduling based on actual water needs, recommendations for optimal fertilizer and pesticide doses, and adjustments to harvest windows tend to reduce water and input consumption per unit produced as well as post-harvest losses due to inadequate handling and uncoordinated logistics. There is also potential contribution to target 12.a insofar as the diffusion of technology and digital competencies in agriculture strengthens scientific and technological capacity in developing countries.

Biodiversity conservation has been accelerated by the Wildlife Insights initiative, a partnership among Conservation International, Google AI, and other institutions. Ahumada et al. [

41] describe the platform, whose computer-vision models are trained on 8.7 million images and recognize more than 700 species. Internal evaluations and user reports indicate accuracy between 80% and 98.6%, depending on the species, and suggest that automation reduces by about 80% the time required to process large camera-trap datasets [

42]. In the Snapshot Serengeti project, a deep-learning application analyzed 3 million images in less than a day and saved more than eight years of manual labeling for each additional batch of the same size, achieving up to 99.3% accuracy [

16,

43]. This acceleration enables much faster responses to anthropic pressures, for example, detecting population declines or anomalous hunting patterns, strengthening SDG 15.

The platform connects directly to targets 15.5 and 15.7 by transforming large camera-trap collections into near real-time information. By anticipating signs of population decline and pinpointing hotspots of illegal human activity, the models support urgent conservation measures, patrol planning, and poaching deterrence. The standardization of metadata and monitoring protocols also favors the integration of biodiversity values into planning and policy decisions, contributing to target 15.9 by providing time series and comparable indicators at local, regional, and national scales. In sensitive ecosystems, continued use of these data also supports target 15.1 by informing assessments of ecological integrity in protected areas and buffer zones.

In the marine domain, monitoring of illegal fishing has been significantly improved by the UK-based organization OceanMind, which combines machine learning with Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, VHF-transmitted by commercial vessels (position, speed, course, and status) and detected by satellite constellations, to track global fishing fleets [

44]. In 2018, this technology helped authorities locate and apprehend the vessel STS-50, responsible for years of illegal Patagonian toothfish fishing, after a pursuit spanning the Indian and Pacific Oceans [

45]. The case highlights AI’s potential to strengthen compliance with fisheries regulations and to contribute to SDG 14.

The combination of AIS data and machine-learning models relates directly to targets 14.4 and 14.5. Identifying anomalous navigation patterns, prolonged high-seas stops, sudden speed changes, and close-proximity vessel encounters allows authorities to infer unauthorized transshipment events, fishing during closed seasons, and incursions into marine protected areas. These signals enable monitoring, control, and surveillance routines; support the application of port-state and flag-state measures; and underpin administrative and criminal sanctions, thereby reducing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and contributing to stock recovery and the conservation of sensitive ecosystems.

There are also potential indirect effects on targets 14.a, 14.b, and 14.c. Improved traceability and operational accountability facilitate the implementation of international ocean-governance instruments, such as regional cooperation agreements and reporting norms, in accordance with the law of the sea. By curbing predatory fleets in coastal areas, the technology protects the livelihoods of small-scale and artisanal fisheries that depend on coastal stocks and expands information bases useful for fisheries management and applied research.

Protection of tropical forests has been scaled through AI-supported bioacoustics. The Rainforest Connection (RFCx) initiative installs solar-powered acoustic sensors in tree canopies and streams forest sounds in real time. In partnership with Huawei Cloud, deep-learning models have raised accuracy to 96% in identifying chainsaw noise in Costa Rica, substantially reducing false positives [

46]. Such acoustic alerts allow enforcement teams to move quickly to detection points, curbing the advance of illegal logging and contributing directly to SDG 15.

RFCx connects directly to targets 15.2 and 15.5. By converting acoustic signals into near real-time georeferenced alerts, enforcement teams can interrupt or deter actions before felling is completed, reducing forest-cover loss and habitat degradation. The system also generates audit inputs for administrative and criminal accountability and provides evidence for sustainable forest management, strengthening the implementation of protection plans and the design of buffer zones.

In global health, epidemiological surveillance has likewise been strengthened by AI: the Canadian platform BlueDot uses natural-language processing across 65 languages and air-travel mobility data to detect outbreaks ahead of official alerts. Niiler [

11] and Caulder et al. [

12] showed that the system signaled an atypical pneumonia cluster in Wuhan nine days before the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020, regarding the then-novel COVID-19 outbreak, illustrating AI’s potential for SDG 3.

Anticipating epidemiological signals via natural-language processing and mobility modeling aligns directly with target 3.d, which calls for strengthened capacities for early warning, risk reduction, and management of health emergencies. By transforming local reports and news into decision-relevant data, systems like BlueDot enable activation of surveillance protocols, intensified testing at strategic points, adjustment of critical-supply inventories, and evidence-based risk communication. There is also potential indirect contribution to target 3.3, insofar as early detection and risk assessment favor rapid responses that limit community transmission and shorten outbreak duration, potentially reducing hospitalizations and mortality.

Taken together, these examples show that Artificial Intelligence can generate public value by reducing risks, increasing resource-use efficiency, and shortening the cycle between detection, decision, and action across health, environment, agriculture, infrastructure, and urban management, contributing to specific targets of SDGs 3, 7, 11, 12, 14, and 15. However, the results obtained in these experiments cannot be generalized, since the studies address local contexts and distinct projects. Realizing these benefits requires well-defined public objectives, auditable models, responsible data governance, and institutional arrangements that ensure transparency, supported by performance and impact metrics reported systematically.

In the

Section 3, the main authors in the research corpus were identified. The following highlights the most relevant contributions of the articles they have published, with the aim of incorporating these authors’ perspectives into the present discussion.

Andreas Holzinger’s articles converge on the interface between XAI, sustainability, and applications in forestry, agriculture, and health. In “AI for life: Trends in artificial intelligence for biotechnology” [

36], AI is positioned as cross-cutting infrastructure for the life sciences and is connected to multiple Sustainable Development Goals, highlighting research gaps in biomedical data mining, ontologies (formal models that standardize concepts and relations), natural language processing, reasoning under uncertainty, and XAI as a methodological agenda for sustainable solutions. In “Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Support Work Safety in Forestry: Insights from Two Large Datasets, Open Challenges, and Future Work” [

47], two large datasets of occupational accidents in forestry are analyzed and decision trees, random forests, and neural networks are compared, incorporating interpretability techniques to support causal inference and accident prevention within the scope of SDG 3 (health and well-being). In “Exploring AI for applications of drones in forest ecology and management” [

48], the potential of AI combined with drones for forest monitoring and management is discussed. In “From Industry 5.0 to Forestry 5.0: Bridging the gap with Human-Centered” [

49], a conceptual framework is proposed that transposes Industry 5.0 principles to the forestry sector with Human-Centered AI, emphasizing predictive analytics, automation, and precision management. In “Human-Centered AI in Smart Farming: Toward Agriculture 5.0” [

50], the focus is on Agriculture 5.0, advocating for the human in the loop in light of Moravec’s paradox (tasks that are easy for humans, such as perception and motor coordination, are difficult for machines, whereas tasks that are hard for humans, such as formal calculation, tend to be easier for computers) and European regulatory requirements, arguing that productivity gains must be compatible with human oversight, ethics, and the resilience of the agri-food system. In “The Cost of Understanding—XAI Algorithms towards Sustainable ML in the View of Computational Cost” [

51], the computational cost associated with explainability in modeling is assessed, scenarios of classification, regression, and object detection are compared in health, building energy, and computer vision, and guidelines are offered for measuring energy consumption and optimizing with emissions metrics. Taken together, these works sustain a research agenda that links XAI, sustainability, and human-centered design as requirements for the responsible adoption of AI in sectors with high operational risk and environmental impact.

Javed Mallick’s articles converge on XAI applications to territorial planning and environmental risk management problems, with an emphasis on integrating Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA), and machine learning. In “A decision-making framework for landfill site selection in Saudi Arabia using explainable artificial intelligence and multi-criteria analysis” [

52], the study combines the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) with fuzzy logic, GIS, and XAI to construct an index of potential landfill areas in a mountainous, rapidly urbanizing context, explaining the contribution of variables such as slope, altitude, land use and land cover, drainage density, and precipitation to support municipal decisions. In “Optimizing Residential Construction Site Selection in Mountainous Regions Using Geospatial Data and eXplainable AI” [

53], a suitability model is proposed for housing developments, articulating fuzzy AHP with a Deep Neural Network (DNN) and explainability layers to interpret determining variables and prioritize safe, environmentally appropriate zones. In “Exploring forest fire susceptibility and management strategies in Western Himalaya: Integrating ensemble machine learning and explainable AI for accurate prediction and comprehensive analysis” [

54], the study advances to forest fire susceptibility using high-performance ensembles and both local and global interpretations to guide management strategies. In “Interpretation of Bayesian-optimized deep learning models for enhancing soil erosion susceptibility prediction and management: a case study of Eastern India” [

55], Bayesian optimization of deep networks and XAI techniques are applied to explain determinants of erosion risk and support soil conservation interventions. Collectively, the works support two central points: the predictive effectiveness of combining classical multi-criteria decision-support methods, machine learning, and explainability in complex geospatial scenarios; and the practical utility of global and local explanations for decisions in sustainable urban development, waste management, wildfire prevention, and soil conservation, aligning technical performance with transparency and accountability in territorial policy design.

The articles by Sergey Zhironkin in the corpus articulate energy and industrial transitions from the perspective of Industry 5.0, Energy 5.0, and Mining 5.0, focusing on human-centered innovation in fossil value chains, alignment with the SDGs, and emissions reduction. In “Fossil Fuel Prospects in the Energy of the Future (Energy 5.0): A Review” [

56], the authors discuss how a non-disruptive transition could reposition fossil fuels through digitization, collaborative AI, digital twins, and the Industrial Internet of Everything (IIoE), adding CO

2 capture and utilization technologies and the use of hydrogen as an energy vector to reconcile energy security with climate goals. In “Review of the Transition to Energy 5.0 in the Context of Non-Renewable Energy Sustainable Development” [

57], Energy 5.0 technological platforms and the human-centered vector of Industry 5.0 are mapped, indicating research fronts for technological diffusion in the hydrocarbons sector. In “Review of the Transition from Mining 4.0 to 5.0 in Fossil Energy Sources Production” [

58], the advance from Mining 4.0 to Mining 5.0 is characterized with emphasis on cyber-physical systems, smart sensors, big data, IoT, and digital twins, and the need to harmonize extraction innovation with the expansion of renewables is discussed. In “Review of Transition from Mining 4.0 to Mining 5.0 Innovative Technologies” [

59], emerging technologies are detailed, such as cobots (collaborative robots that work alongside humans in production and service environments), cloud mining (use of cloud computing for the analysis and management of mining operations), bioextraction (use of microorganisms and bioprocesses to recover metals and minerals), post-mining practices (closure and environmental and socioeconomic rehabilitation after extraction), and ESG investment, arguing that a human-centered orientation and digital–biotechnological integration are prerequisites for reshaping the role of the mining sector in a low-carbon economy. Taken together, these studies aim to delineate barriers and modernization pathways for fossil and extractive chains, reconciling productivity, occupational safety, climate goals, and the SDGs within the horizon of Industry, Energy, and Mining 5.0.

Karl Stampfer’s articles in the corpus lie at the interface of forestry operations, XAI, and a human-centered agenda for sector modernization. In “Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Support Work Safety in Forestry: Insights from Two Large Datasets, Open Challenges, and Future Work” [

47], coauthored with Andreas Holzinger, two large real-world datasets of occupational accidents in Austria are analyzed to compare decision trees, random forests, and fully connected neural networks, incorporating interpretation layers and an emphasis on causal inference with the goal of accident prevention and alignment with SDG 3. In “Exploring artificial intelligence for applications of drones in forest ecology and management” [

48], also coauthored with Andreas Holzinger, the potential of AI combined with drones for forest monitoring and management is discussed, highlighting gains in detection, mapping, and decision support. In “From Industry 5.0 to Forestry 5.0: Bridging the gap with Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence” [

49], likewise coauthored with Andreas Holzinger, the transition from Industry 5.0 to Forestry 5.0 is synthesized, proposing a framework that articulates predictive analytics, automation, and precision management with human oversight, occupational safety, and sustainability. Stampfer’s contribution reinforces the responsible adoption of AI in environments with high operational risk, focusing on safety, efficiency, and sustainable forest management, and it remains thematically consistent with the coauthored works with Andreas Holzinger.

However, the promise that Artificial Intelligence will act as an accelerator of Sustainable Development, contributing to goals such as energy efficiency, tackling climate change, and supporting the decarbonization of sectors such as energy, transport, and natural resource management, is inseparable from a structural paradox: the computational infrastructure required to train and operate AI systems, especially large-scale deep learning and natural language models, demands increasing volumes of energy and material resources, contributing in a non-negligible way to global greenhouse gas emissions [

60,

61]. Carbon footprint studies for scientific computing show that the environmental impact of the same experiment can vary by orders of magnitude depending on the carbon intensity of the electricity mix, the energy efficiency of data centers, and the choices of architecture and training, which highlights the central role of the energy context in assessing the sustainability of AI [

62,

63]. This variability reinforces that the sustainability of AI is intrinsically linked to the decarbonization of digital infrastructure. In parallel, recent projections indicate significant growth in energy consumption associated with data centers and AI workloads in the coming decade, which intensifies the tension between the indirect climate benefits generated by AI applications and the environmental costs of their own operation [

60,

61]. Distinguishing direct impacts of AI computing, often discussed from the perspective of “Green in AI”, from indirect impacts of applications that help reduce emissions in other sectors, associated with the notion of “Green by AI”, authors such as Kaack et al. [

60] and Verdecchia, Sallou, and Cruz [

63] argue that net gains will only be positive when the emissions mitigation enabled by applications outweighs the carbon footprint of the development, training, operation, and disposal of AI infrastructure. In this sense, these analyses advocate the need for measurement and transparency standards regarding energy consumption, emissions, and the use of natural resources, so that the reduction in the environmental footprint of AI systems becomes a central methodological axis in HCAI approaches.

Considering Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, the effectiveness and legitimacy of these applications depend on participatory design, bias mitigation, and safeguards for vulnerable populations, as well as attention to side effects such as digital exclusion, undue surveillance, and infrastructure overload. When integrated into public policies and supported by public–private commitment to implementation, these applications move beyond isolated proofs of concept and gain the potential to become replicable instruments for advancing Sustainable Development.

5. Conclusions

The study, based on a bibliometric and interpretive analysis of the scientific literature, evidenced the marked growth and thematic diversification of research that articulates Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HCAI) and Sustainable Development. The concentration on topics such as Explainable AI, Industry 5.0, and AI Ethics confirms the consolidation of an interdisciplinary field oriented toward the responsible application of emerging technologies.

The research question was addressed by demonstrating that the recent literature is structured around three interdependent dimensions, technical, ethical, and socio-environmental, which express the advancement of HCAI as a vector for accelerating the Sustainable Development Goals. Nevertheless, significant regional and thematic gaps persist, especially in countries of the Global South. The literature reinforces that the promise of Artificial Intelligence acting as a vector for Sustainable Development clashes with the fact that many solutions are conceived based on data, infrastructures, and regulatory frameworks from the Global North and subsequently transplanted to peripheral contexts without adequate local adaptation. Studies on decolonialism warn that AI projects that do not acknowledge historical power asymmetries tend to reproduce forms of coloniality, rendering invisible local knowledge, languages, and territorial priorities in the Global South [

64]. International initiatives focused on AI and social impact emphasize the need to calibrate models, data, governance, and success metrics to the specific realities of countries in the Global South, precisely to avoid widening the digital divide and inequalities in access to the benefits of technology [

65].

Empirical evidence on the convergence of efficiency in the use of natural resources between the Global North and South indicates that countries with greater capacity to adopt AI and lower geopolitical risk tend to disproportionately capture productivity and sustainability gains, while Southern economies remain in positions of technological and financial dependence, including with regard to digital infrastructures, intellectual property, and investment flows associated with AI [

66]. The studies suggest that AI solutions not adapted to local contexts can shift the Sustainable Development agenda toward priorities defined by the Global North and perpetuate global inequalities in the distribution of the risks and benefits of AI.

This study focused on open-access, English-language publications, which may have excluded significant contributions in other languages or from countries with lower presence in international journals, especially in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Furthermore, the attribution of country in the counts presented in the results considered only the affiliation of the corresponding author, which may underestimate the participation of researchers from Global South countries in international collaborations. Future research may explore regional scientific production and examine how different sociotechnical and regulatory contexts shape the adoption of HCAI. Additionally, the choice of certain keywords over others may have led to the exclusion of some relevant studies on the topic.

The results contribute by offering a panoramic and systematized view of the main global trends, scientific collaboration networks, and emerging research axes. In practical terms, the study supports the design of future scientific and policy agendas capable of integrating technological innovation, ethical governance, and environmental sustainability. The study also contributes meaningfully to knowledge advancement by integrating the perspective of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence with the principles of Sustainable Development through an unprecedented bibliometric-interpretive mapping approach. Theoretically, it provides a comprehensive systematization of the ethical, technical, and socio-environmental dimensions that structure HCAI, strengthening its understanding as an emerging interdisciplinary paradigm. Methodologically, it proposes a replicable analytical strategy based on the triangulation among production metrics, collaboration networks, and thematic groupings, thereby expanding its applicability to other scientific domains. In practical terms, the findings inform public policies, business strategies, and governance initiatives geared toward the responsible adoption of AI in support of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite its reach, the temporal delimitation of 2020–2024, although justified by the recent consolidation of the HCAI concept, constrains the observation of historical trends and the tracking of the field’s earlier evolution. Future research may expand this window to encompass the conceptual origins and progressive maturation of the human-centered approach. In addition, more integrative methodological designs are recommended, articulating bibliometric methods, systematic reviews, and content analyses to enable a critical assessment of HCAI’s theoretical foundations, contexts of application, and ethical implications.

Considering these findings, a scientific agenda for advancing the use of Artificial Intelligence in addressing the contemporary problems envisaged in the 2030 Agenda should prioritize research oriented toward concrete SDG challenges, articulating advanced algorithmic capabilities with deep sectoral knowledge and qualified social participation. Landmark studies indicate that AI can support many SDG targets while at the same time creating risks and distributive tensions, which requires research programs capable of integrating impact assessment, governance, and socio-environmental justice [

3]. Within this horizon, national policies in support of the SDGs can play a strategic role by explicitly linking AI strategies to objectives such as sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) and climate action (SDG 13), combining public funding, regulatory incentives, capacity building, and mechanisms of intersectoral coordination to steer innovation toward Sustainable Development.

In sum, the findings reinforce that consolidating a genuinely human-centered Artificial Intelligence requires balancing technological innovation with ethical values, promoting a digital transition that is simultaneously inclusive, transparent, and sustainable. HCAI thus emerges as a promising pathway for harmonizing scientific progress and social responsibility, contributing to the construction of more resilient societies aligned with the challenges of the twenty-first century.