5.1. Hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4

Based on the descriptive statistics, with a strong consensus in the sample, respondents perceive reskilling opportunities to be extremely important (mean = 4.07, standard deviation = 0.67). This correlates with a study by Rahiman and Kodikal (2024), which indicated that students who are optimistic about enhancing their skills also have the ability to collaborate more effectively and improve their educational outcomes [

64]. On the other hand, institutional support (mean = 3.4, standard deviation = 0.78) and curriculum relevance (mean = 3.16, standard deviation = 0.93) are rated moderately, showing a greater variety in perceptions and indicating potential areas for improvement in aligning education with labor market demands, as shown by UNESCO’s report [

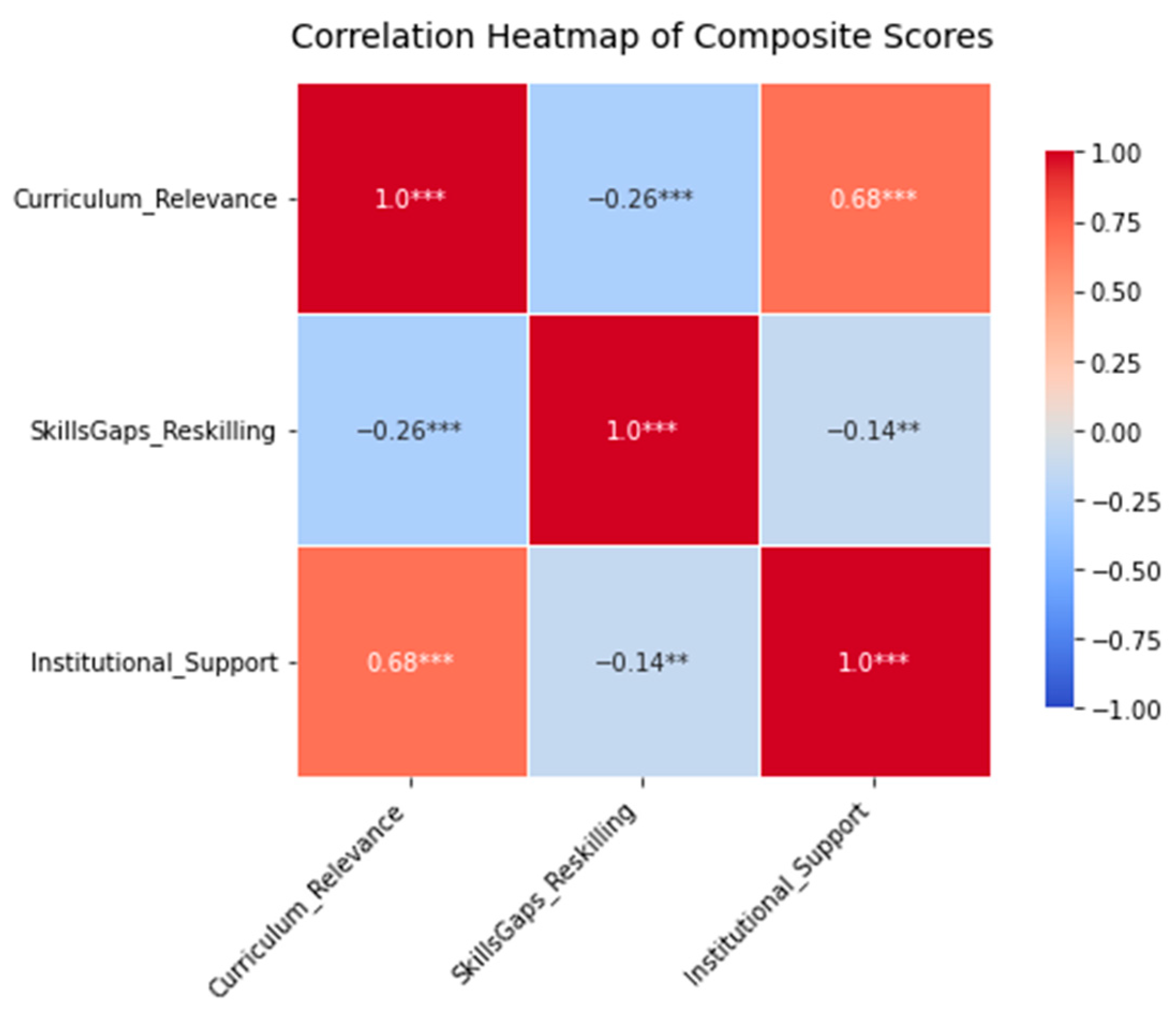

54]. As the latter two variables are strongly intertwined and negatively correlated with perceived skills gaps, it seems that when universities provide support and relevant curricula in the AI era, graduates report less need for reskilling; this is also supported by [

53]. Curriculum alignment and institutional support are strongly positively correlated, implying that when graduates perceive their universities’ curricula as being adapted to the actual needs of the market, they also tend to believe that their universities contribute to sustainable human capital development. The symbiosis between the two variables can occur with effective strategies of training teaching staff [

17]. When it comes to Romanian universities, a survey of 856 Bachelor’s graduates showed that there is an excess of theoretical knowledge in comparison with practical or digital skills, suggesting that these skills do not sufficiently align studies with job requirements so as to improve graduates’ job satisfaction [

65]. At the same time, a World Economic Report suggested that in Romania, less than 30% of companies consider university degrees as an important employment factor [

50]. These discoveries unravel the interplay between curriculum design, universities’ support, and graduates’ perceptions of skills adequacy. Continuous reskilling will remain an imperative in the AI era, as some statistics reveal. For example, the World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2023 report predicted that 6 in 10 workers will need retraining before 2027, mostly in the area of analytical thinking [

50]. The same report highlighted how 52% of the reskilling focus should be placed on “AI and big data” in Romania and that providing effective reskilling and upskilling opportunities is considered a good business practice to improve human capital availability in the country [

50]. One study on students from Zagreb, conducted by Dužević et al. (2025) [

66], identified four key dimensions that shape students’ experiences with artificial intelligence chatbots (AICBs) in higher education: quality, usability, mistrust, and adoption. Although students in the research reported moderate to high overall experiences with AICBs, the findings highlighted that trust in AI has not fully developed, and institutional guidance is still needed to support responsible integration. The idea that generative chatbots have a supportive rather than substitutive role in university education was found in a study on Bulgarian undergraduate and graduate students in majors like Economics, Public Sector Management, and Business Management [

67]. These chatbots may enhance blended learning by improving engagement, personalization, and efficiency, but only when used under the guidance of instructors, within clear ethical boundaries, and with awareness of their limitations [

67].

The correlation insights focus on the role of retraining among graduates. Being strongly correlated, questions Q16 to Q19 reveal that when reskilling is prioritized, other factors, such as skills readiness and job experience, are improved at the same time. This finding corresponds with the literature [

15]. Thus, it is crucial for universities to design integrated programs that relate to practical job experience by offering opportunities for internships and applied projects, to provide reskilling opportunities by coming up with bootcamps and short courses, and to bridge the skills gap by offering opportunities for targeted upskilling and mentorship. Romania’s low digital literacy rate of 27.7%, as reported in 2023, compared with the EU average of 55%, raises crucial debates on whether the Romanian educational system is prepared to adjust curricula to equip students with essential AI and digital skills [

68]. However, the EU Digital Decade 2025 report stated that digital skill levels correlate with educational attainment in Romania, meaning that while the percentage of digital skills level rises to 63.93% among those with higher education, it is still less than the 79.83% EU average [

69]. These misalignments were acknowledged by policymakers, and Romania’s 2023 higher education law explicitly emphasized aligning academic programs with labor market requirements regarding emerging digital professions [

70]. For higher education institutions to successfully address AI in their curricula, as the level of preparedness in Q12 is negatively correlated with reskilling and skills gaps, specific learning paths should be built based on skills assessments and personalized recommendations for students. Moreover, formal and non-formal activities can support the continuous digital training of teaching staff and students. Therefore, improving the digital infrastructure in universities, stimulating educational units and institutions for educational offers with specializations and digital qualifications, creating digital educational tools, finding interactive student-centered educational solutions, creating “attractive Open Educational Resources”, and developing public–private partnerships by participating in digital networks may be some of the answers to the issue of effectively integrating AI into higher education institutions [

71]. A study on Hungarian university professors conducted by Dringó-Horváth et al. (2023) found that there is a stronger correlation between digital competence and AI literacy among male teachers in the information technology field than among female teachers in fields like “humanities, social sciences, and health sciences” [

72]. Higher education institutions should ensure that their AI adoption plans are fully aligned with educational goals and that higher education providers support the development of AI literacy and digital skills among both professors and students [

73]. The more prepared employees feel, the less they feel they lack the necessary skills to adapt to technological challenges. Reskilling programs should simulate actual job tasks.

One other finding in our analysis is that support from universities for students’ AI preparedness is only partial, moderate, and uneven across institutions. This is also supported by a 2023 qualitative study of Romanian academics, which mentioned that there is a lack of a clear strategic vision for implementing AI in Romanian higher education, as digitalization in Romanian universities “is still in its infancy” [

36]. Because there is no consistent, coordinated national approach, support for AI skills or AI integration has the tendency to depend on individual projects of faculties [

70]. A lack of a shared vision for AI infrastructure in universities was also discovered in a study from 2024 on 18 Bulgarian universities, which were responsible for digitalization, as well as financial resources and administrative capacity scarcity and resistance from the administrative and academic staff [

74]. Although the National AI Strategy (2024–2027) recognizes education and skills development as priorities, it only provides guidelines rather than concrete implementation plans, and the responsibility to design specific measures is left to universities and ministries, illustrating a moderate commitment level [

46,

47,

65]. While AI readiness programs exist, they are not uniformly and strongly spread across all Romanian higher education institutions. In Bulgaria, as a study by Simeonov et al. (2024) revealed, AI education is starting to take over dedicated subjects and programs in BSc and MSc degrees in Information Technologies and Computer Sciences, while other adjacent academic fields, like Electrical Engineering, Electronics, and Automation, lack the necessary AI training for students, even though they too face rapid technological shifts [

75]. This fact suggests that new professionals in these fields and other non-IT ones will need “longer onboarding periods or additional training” when transitioning from university to industry [

75].

The survey’s results validate Hypothesis 1 (H1), Hypothesis 2 (H2), Hypothesis 3 (H3), and Hypothesis 4 (H4).

5.2. Hypotheses H5 and EH5

The findings indicate that respondents’ perceptions of AI preparedness and reskilling are influenced less by current job AI exposure and influenced more by workplace satisfaction and the adequacy of prior university training. In contrast with the literature that suggests a relationship between AI preparedness and exposure to AI at work [

56,

57,

58], our results illustrate that the Romanian graduates in the survey do not feel more prepared to work with AI tools, even though they may encounter them in their jobs. Further studies should be conducted on Romanian graduates regarding the correlation between the two variables based on more niche professions and the corresponding university affiliations of respondents. Although Hypothesis 5 (H5) was not validated in the first place, a secondary hypothesis was tested. The secondary exploratory hypothesis elaborates on the idea of the overall work experience and collective impact on AI resilience, as stated in the study by Majrashi K (2025) [

59]. Our findings demonstrate that job satisfaction predicted AI confidence more accurately in the sample. This means that broader work experiences play a more important role in the level of preparedness than direct technological exposure, suggesting that the more nuanced Hypothesis EH5 is accepted. One other study identified the same ideology that job satisfaction significantly and positively affects employees’ readiness for organizational change [

76]. Although more training after graduation does not impact AI confidence, graduates who feel happier with their current employment context are also more confident in adapting to AI. So, exposure to advanced technologies alone does not automatically translate into confidence, which is the case in our sample—the respondents in AI-intensive jobs did not report markedly higher adaptability confidence unless they also reported high job satisfaction. A survey conducted by Gallup and Amazon discovered that 71% of workers who upskilled saw an increase in their overall job satisfaction [

77]. This further means that a supportive work environment and personal fulfillment have the capacity to foster a mindset open to change, arguably more so than just having access to and working with AI tools on a daily basis. The risk imposed by AI job substitution lowers the level of employees’ work satisfaction [

78]. Job satisfaction, in contrast with technical exposure, represents a more holistic and long-term motivator due to recognition, work–life balance, relationships, and its ability to ensure that employees remain committed to their work performance [

79]. While digital solutions integrated at the company level offer opportunities for employees, areas like “communication, collaboration, flexibility, feedback, and recognition, as well as personal and professional development” are as essential [

80]. Furthermore, work satisfaction results in promotions, which can be achieved through coaching, mentoring, or training sessions so that employees acquire the necessary additional skills [

81]. Long-term effective AI adoption and integration in organizations is derived from employees’ satisfaction, as concluded by another study [

82]. Consequently, psychological and professional alignment of graduates’ jobs may be just as essential as AI exposure at work in fostering AI preparedness. Confidence in adapting to AI-related changes may be achieved through training programs and supportive management. Future research could focus on how job autonomy, satisfaction, and perceived skill use act together in adopting AI for adaptability in the labor market.

5.3. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Although the sample size of 365 is adequate for an exploratory analysis, the sample is not fully representative of the national level. The distribution of respondents is uneven across subgroups, as women (69%) and young graduates aged 21–25 (66.6%) are overrepresented. These aspects may limit the external validity of our findings and the extent to which the results can be generalized to the wider population of graduates.

The data were collected at one point in time and the ability to infer causal relationships is limited. This could mean that higher job satisfaction can lead to higher AI confidence; however, it could also mean that more confident graduates feel more satisfied with their current jobs. This is one of the shortcomings of perception analyses. Moreover, respondents may not be very objective when rating their skill levels and actual AI exposure and knowledge. The self-selection bias should be taken into consideration because respondents who were more active online, more motivated to respond to surveys, or more engaged with academic networks in general may be overrepresented in the sample.

In the case of H5, the hypothesized predictor, namely, job AI involvement (Q27), revealed only weak effects on AI confidence, implying that some unmeasured variables, such as workplace learning opportunities, personality traits, or organizational culture, could actually be impactful.

Future research recommendations include using panel data to track the evolution between graduates’ confidence and job changes, additional training, and AI adoption. Potential experimental studies could test causal impacts on confidence and preparedness. Instead of self-report measures, some other external indicators could be used, such as company-level AI adoption or occupational exposure indices. Also, factors like personality traits, training opportunities, or organizational support could be tested so as to better shape the relationship between job factors and AI confidence. International comparisons, cultural, and sectoral differences could be integrated in future research as well.

Other research implications could focus on cross-country or cross-sector analyses in order to compare the present findings across different national, cultural, and industry contexts. Such cross-analyses could reveal whether curriculum gaps and institutional support issues are common elsewhere or specific to the Romanian higher education system.

To strengthen generalizability, future potential studies should aim to collect nationally representative samples and consider stratified sampling to balance key demographics, such as gender, age, or region. Longitudinal or comparative studies could further validate the current findings across different cohorts of graduates.