Medium-to-Long-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Newly Constructed Canals Based on Navigation Traffic Volume Cascade Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

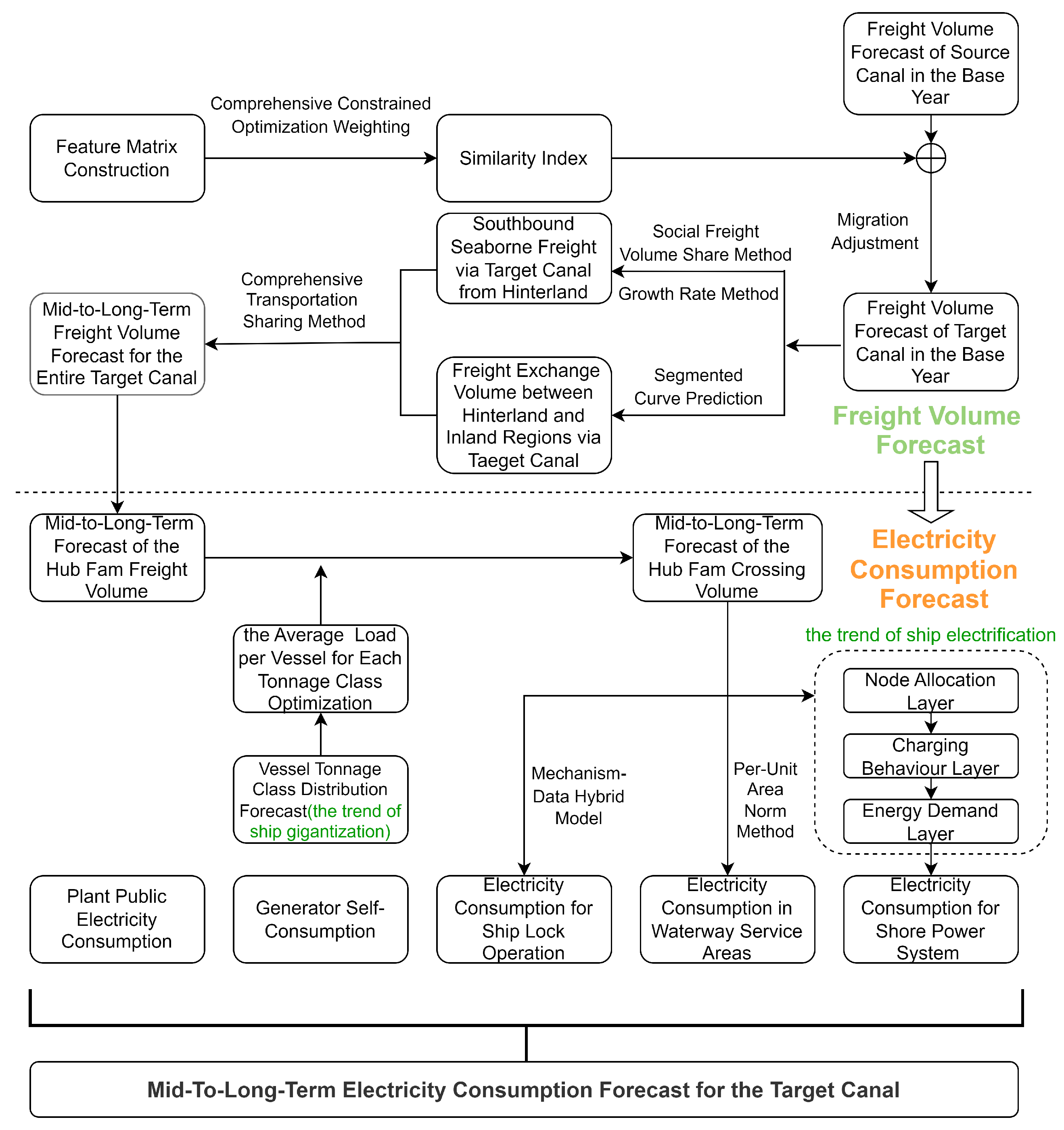

- A multisource feature transfer framework is proposed to construct a six-dimensional feature matrix that includes economic, meteorological, and facility constraints. This framework transforms load forecasting into a prediction of ship transit volumes/cargo volumes. The independence of features and their correlation with cargo volumes are verified through correlation analysis. Feature weights are calculated using a comprehensive constrained optimization weighting method, and the canal-to-canal similarity index is quantified using weighted Euclidean distance to generate multisource fusion weights, achieving the cross-project transfer of cargo volumes.

- An cascaded prediction chain of “cargo volume–transit volume–electricity consumption” is established: First, the cargo volume for the target canal is predicted by integrating the logistic saturation correction method and the comprehensive transportation sharing method. Then, a tonnage-ship number dynamic mapping model is developed to convert cargo volumes into transit volumes based on the trend of ship gigantization. Finally, a ship lock electricity consumption mechanism-data hybrid model and a three-layer “Node–Behavior–Energy” (NBE) prediction framework for shore power are constructed based on the core variables of transit volumes to collaboratively predict the electricity consumption across the entire process.

2. Multisource Data Migration Architecture for Electricity Consumption Forecasting of a Newly Constructed Canal

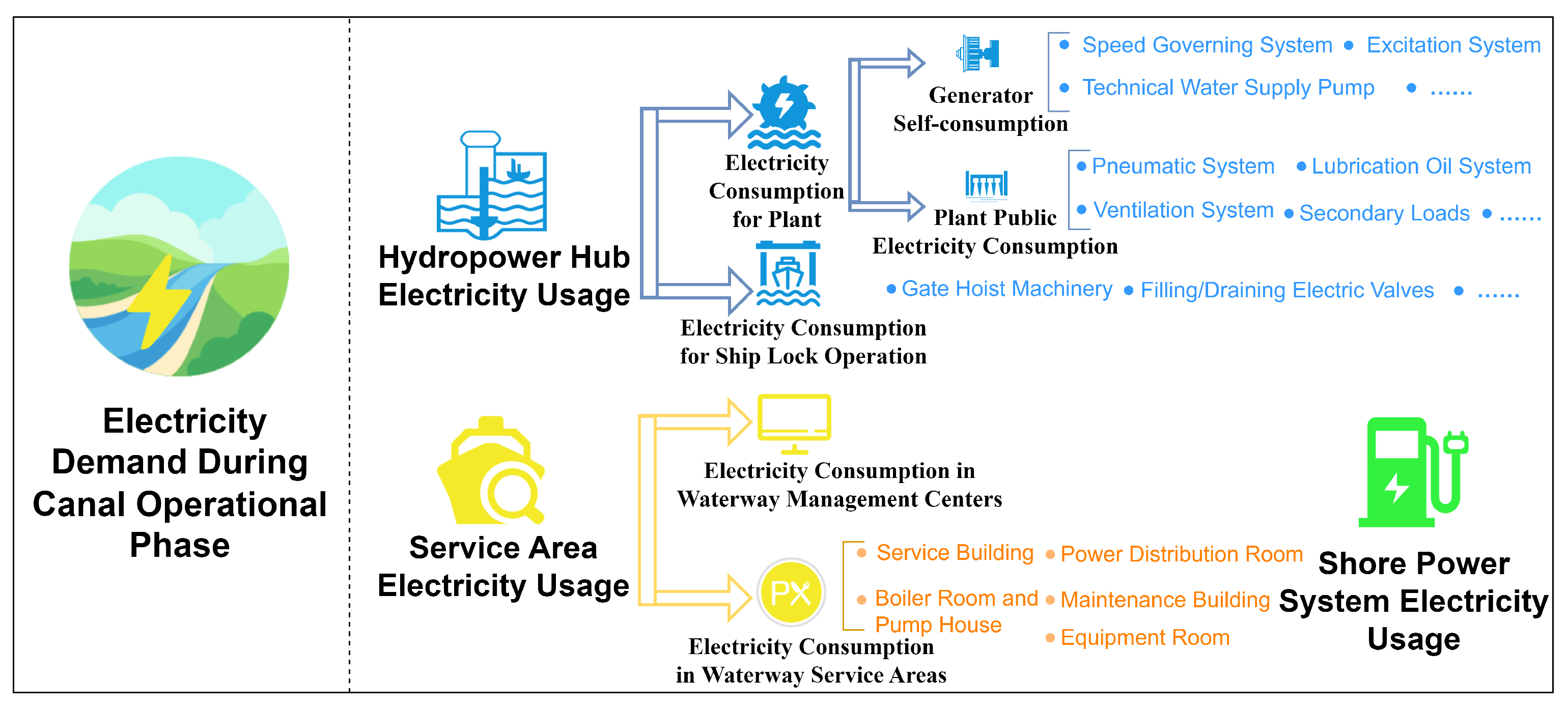

2.1. Analysis of Typical Electricity Consumption Scenarios for Canals

2.2. Analysis of Driving Factors and Feature Extraction for Electricity Consumption Characteristics

2.2.1. Characteristic Driving Factor Analysis and Feature Matrix Construction

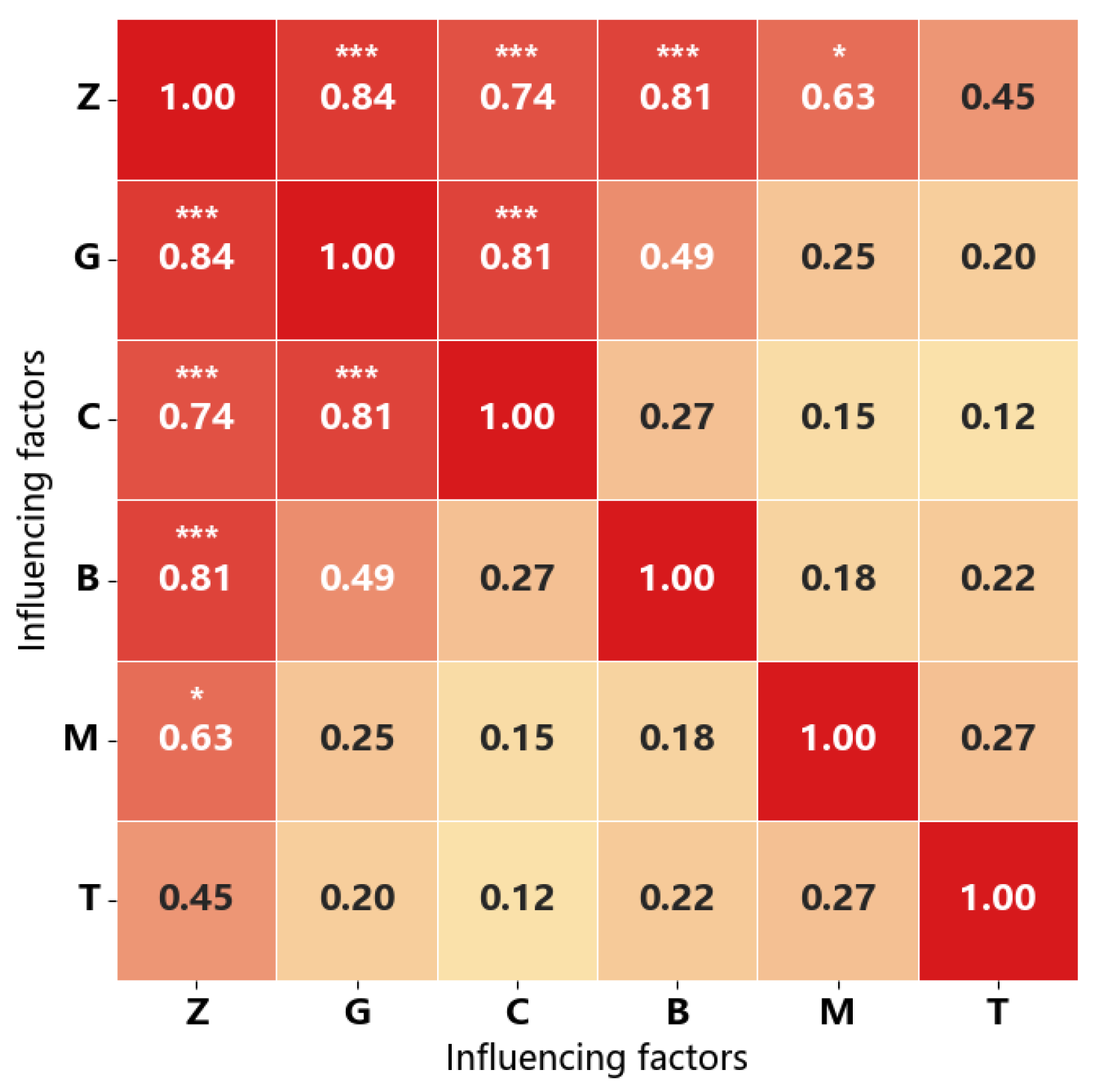

2.2.2. Feature Driver Correlation Analysis

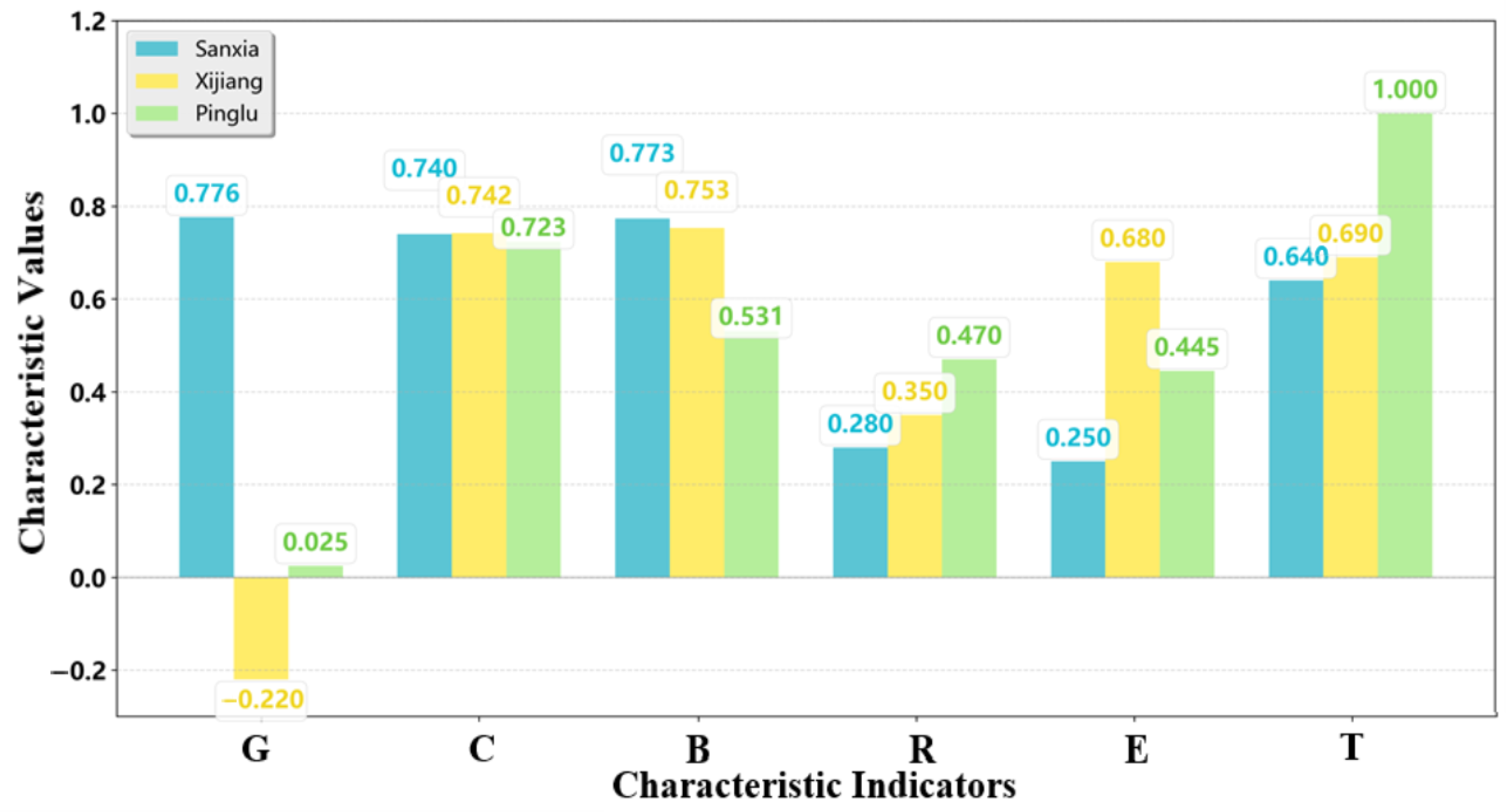

2.3. Feature Transfer Based on Similarity

3. Electricity Load Forecasting Based on Navigation Traffic Volume Cascade Mapping

3.1. Mid-to-Long-Term Navigation Traffic Volume Forecasting Model

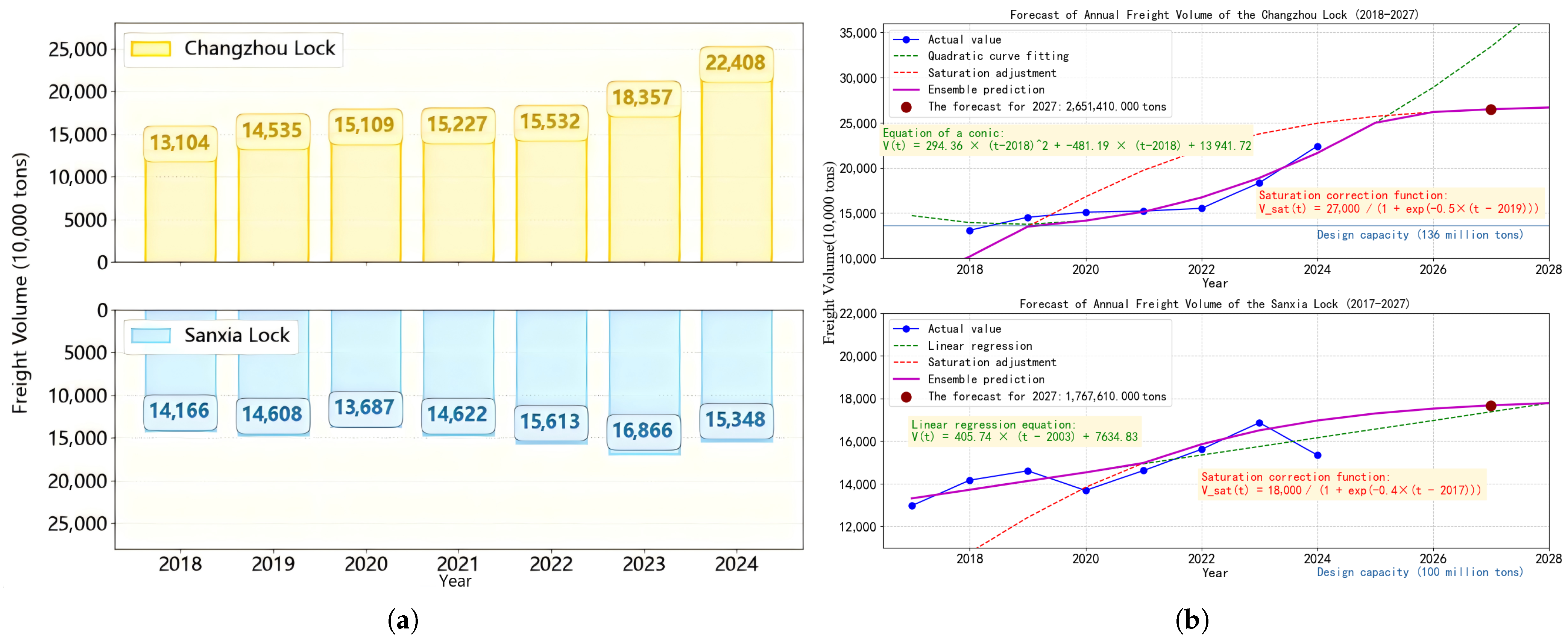

3.1.1. Mid-to-Long-Term Freight Volume Forecasting

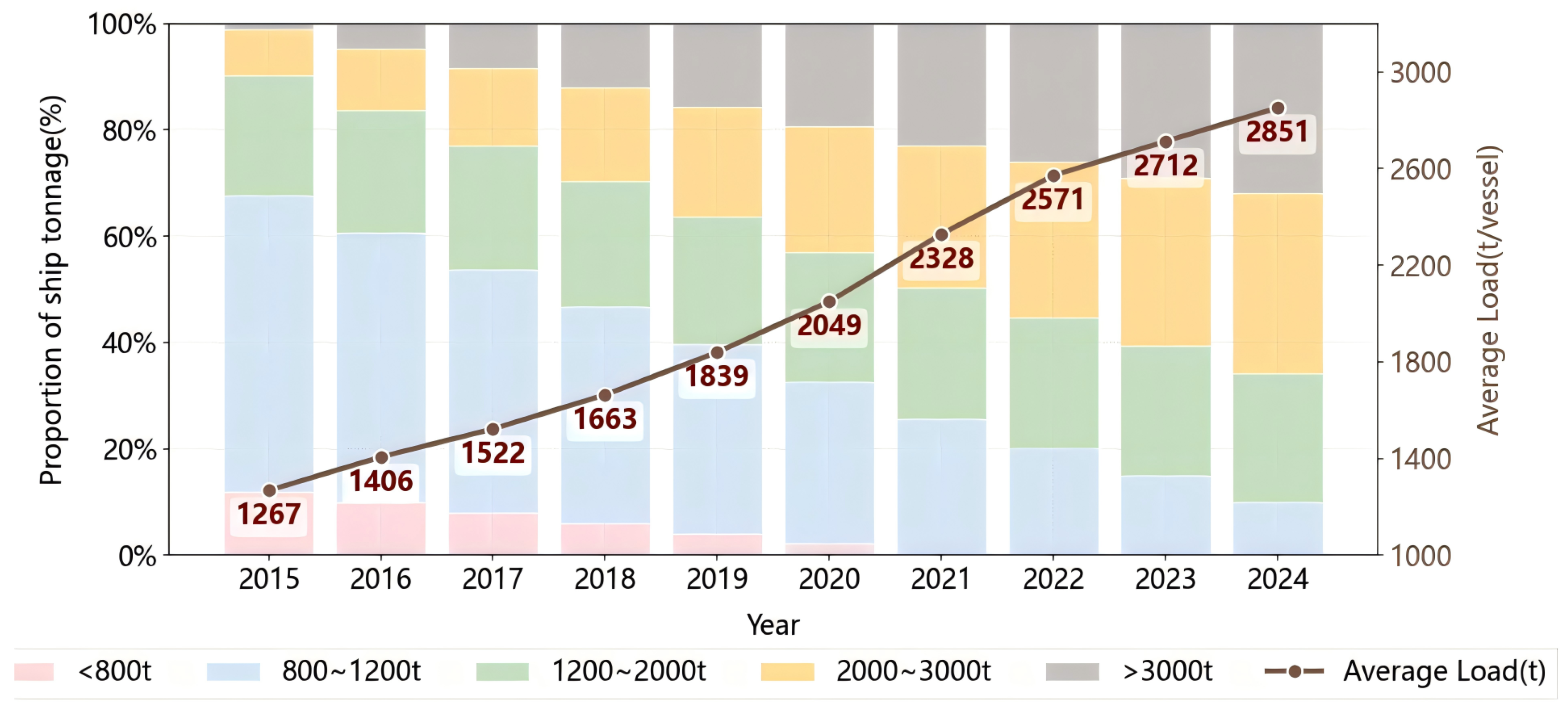

3.1.2. Mid-to-Long-Term Ship Gate-Crossing Volume Forecasting

3.2. Mid-to-Long-Term Electricity Demand Forecasting Model

3.2.1. Mid-to-Long-Term Electricity Use for Water Control Projects

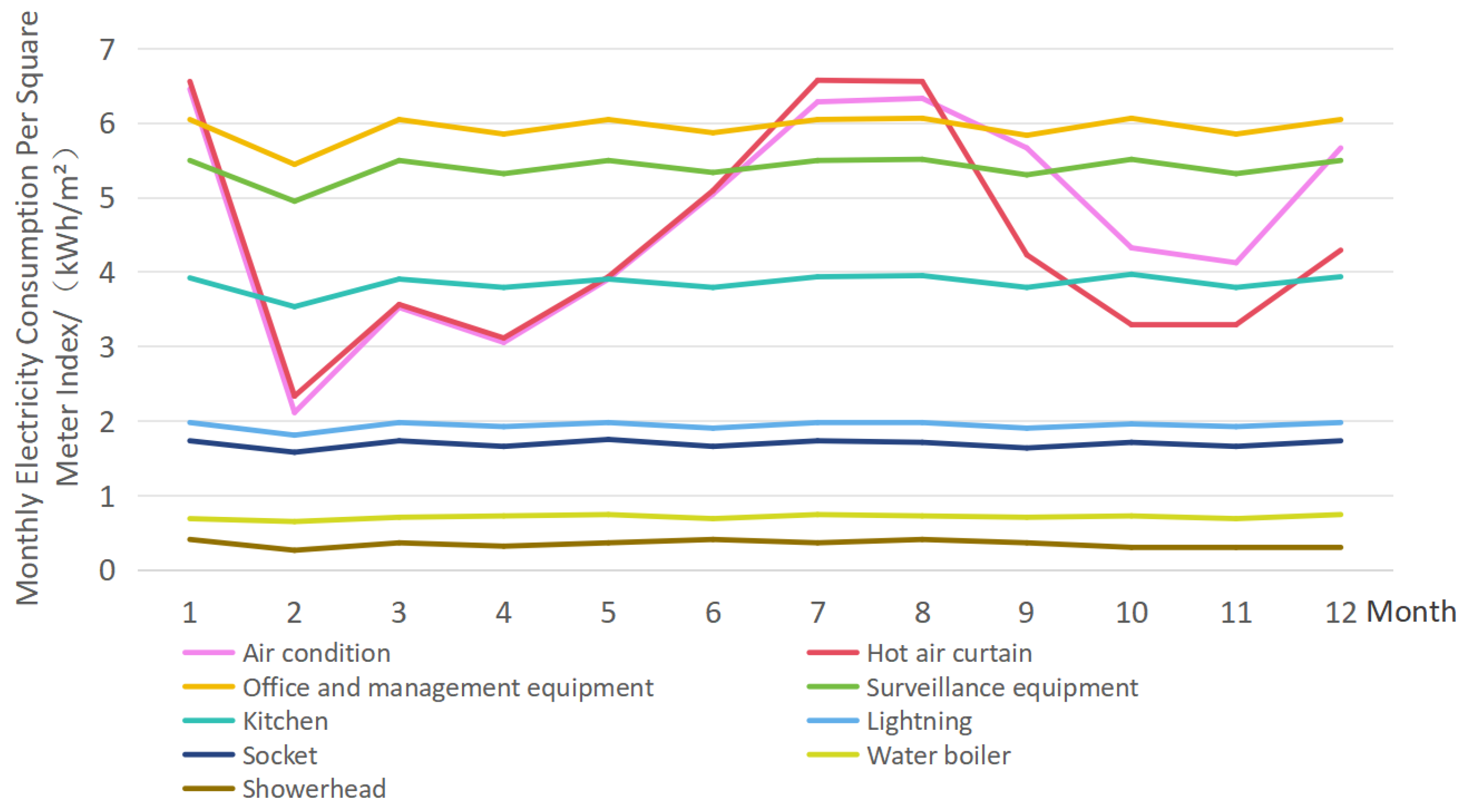

3.2.2. Mid-to-Long-Term Electricity Consumption in Waterway Service Areas

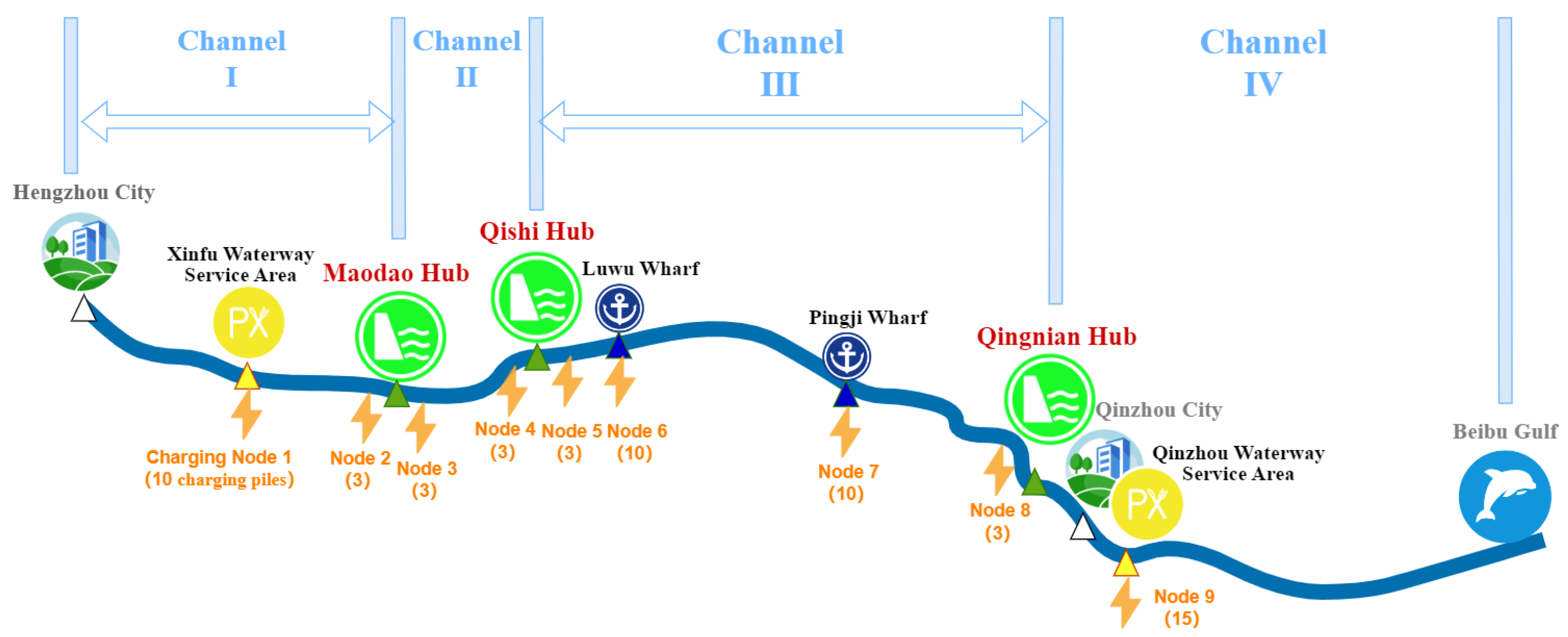

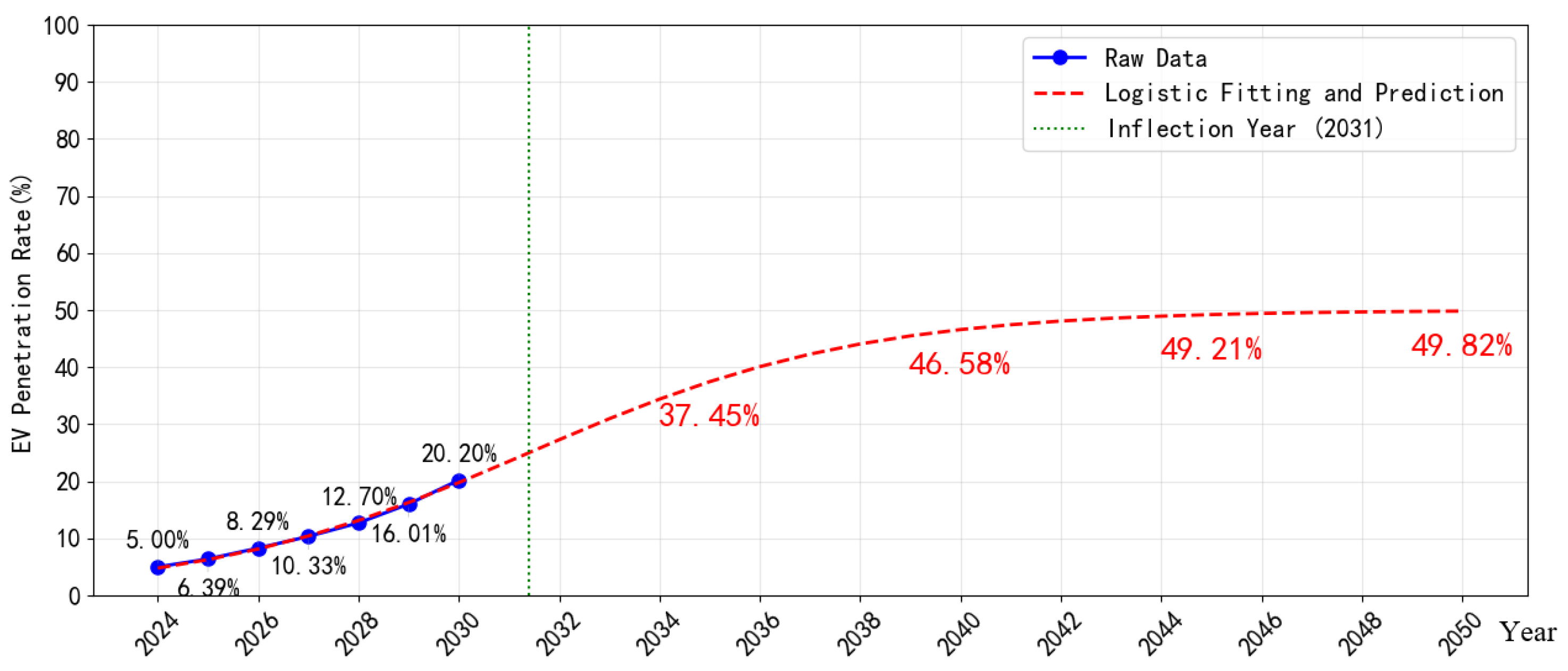

3.2.3. Mid-to-Long-Term Electricity Consumption in Shore Power Systems

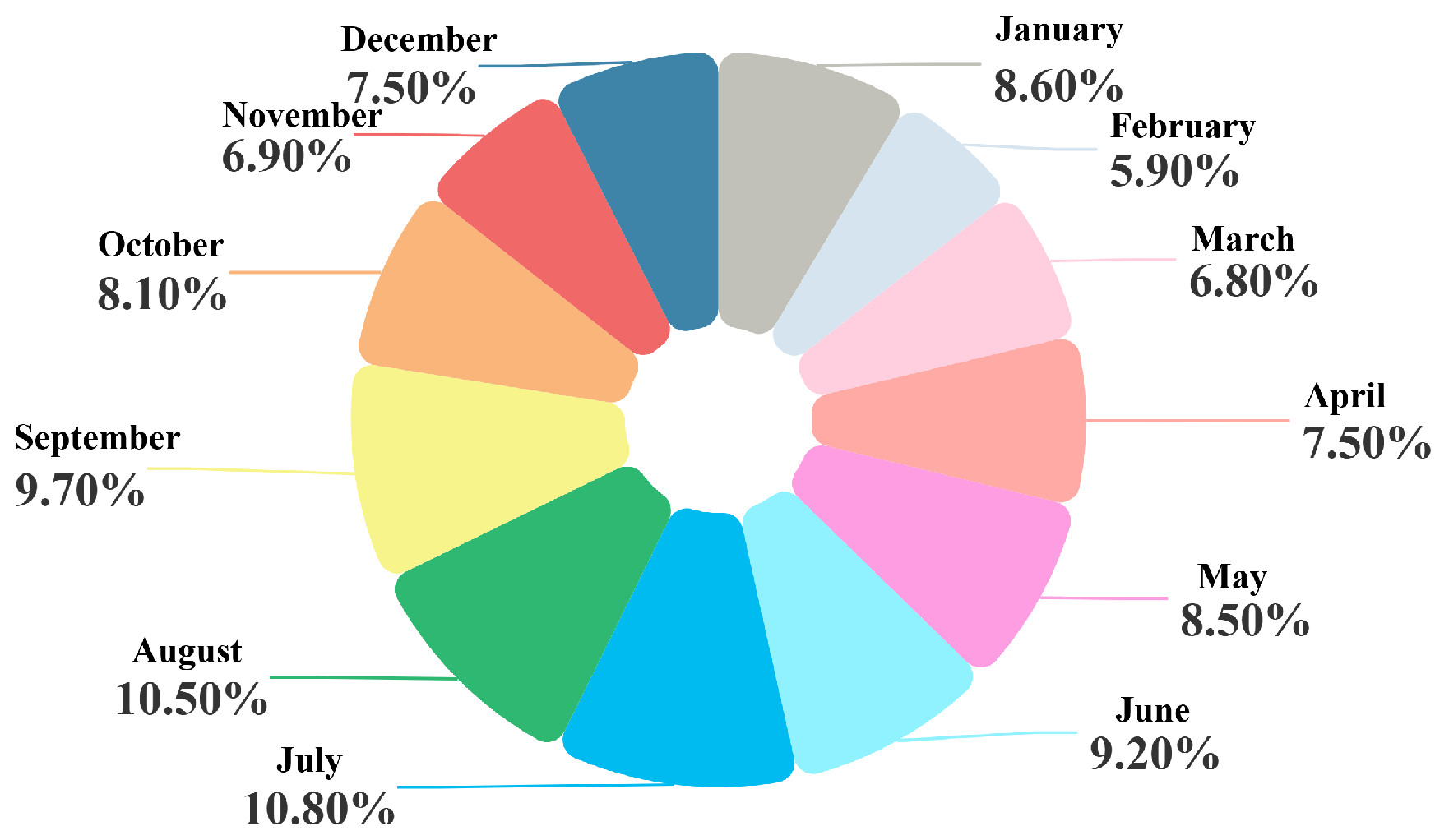

3.3. Monthly Electricity Consumption Decomposition Based on Lock-Through Traffic Volume Impact

4. Case Analysis

4.1. Similarity Calculation Between Pinglu Canal and Source Canals

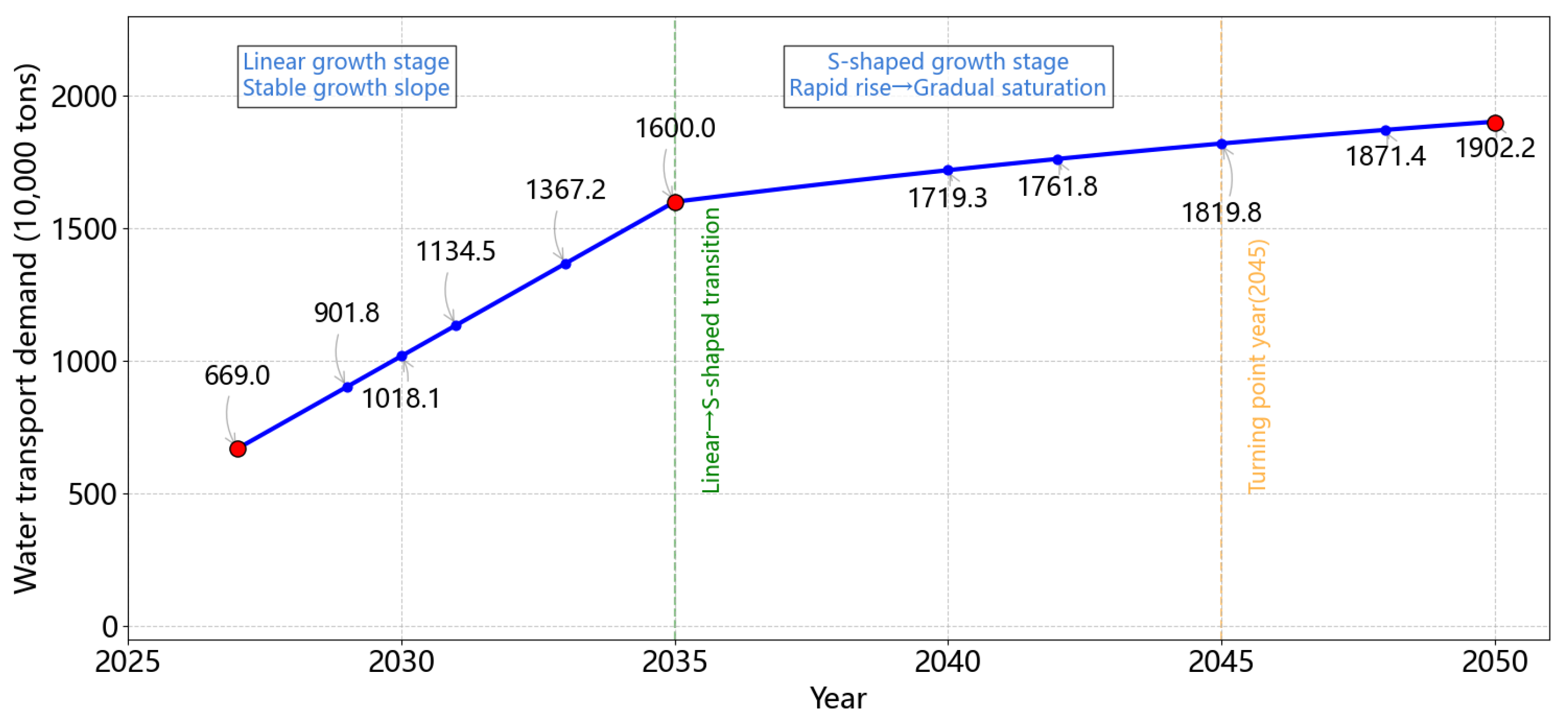

4.2. Mid-to-Long-Term Navigation Volume Forecast for Pinglu Canal

4.2.1. Mid-to-Long-Term Freight Volume Forecast

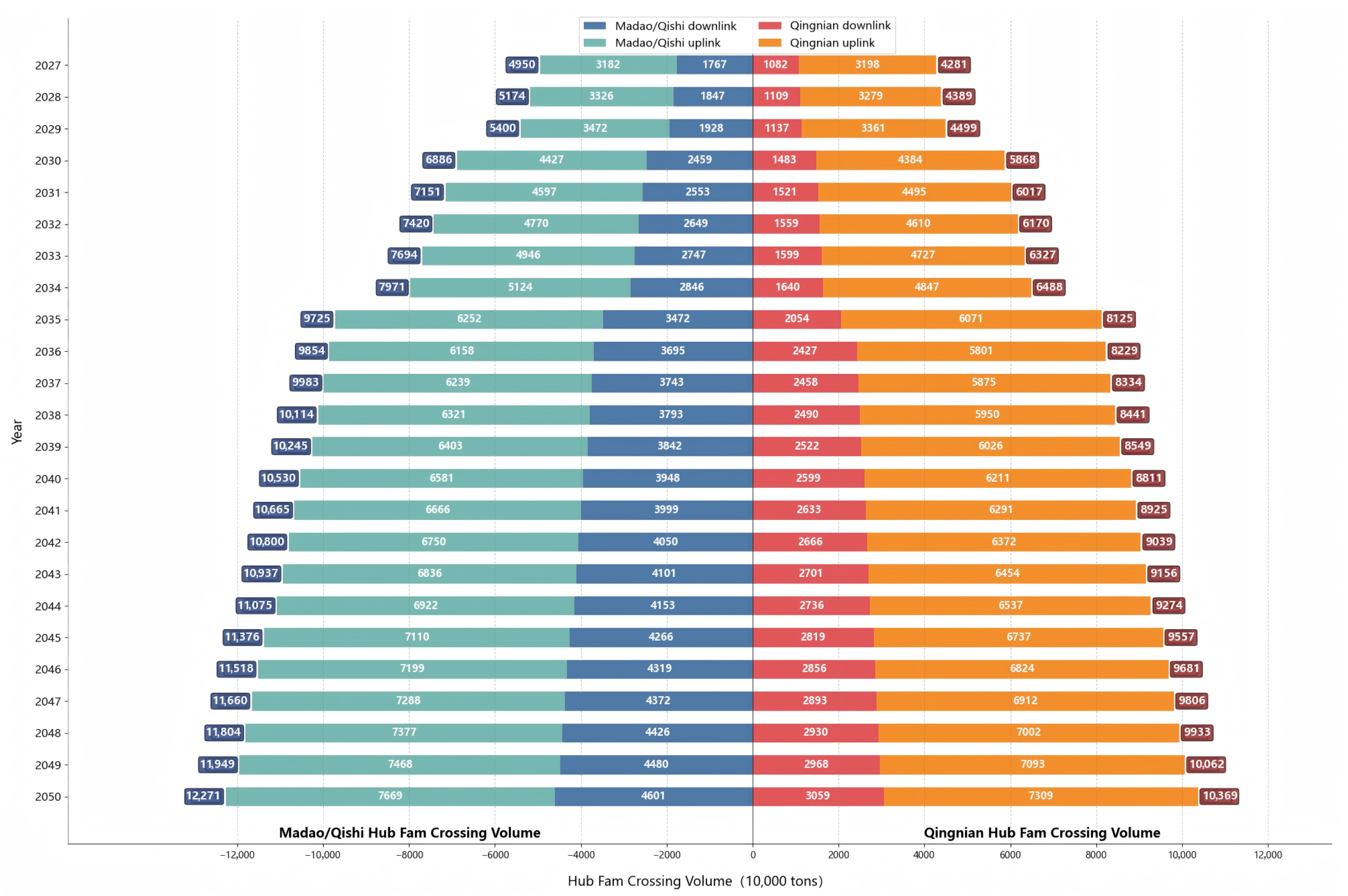

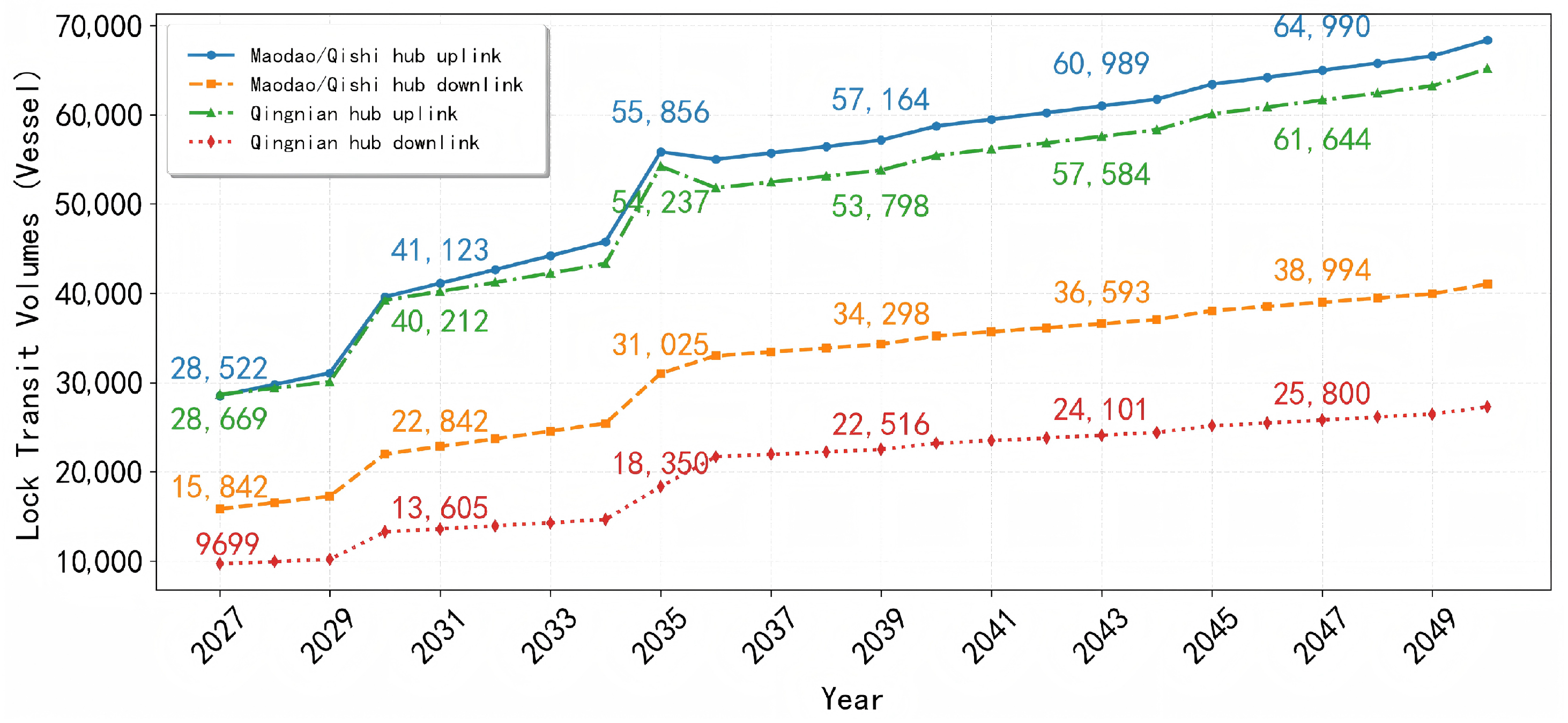

4.2.2. Mid-to-Long-Term Lock Transit Volume Forecast for Pinglu Canal

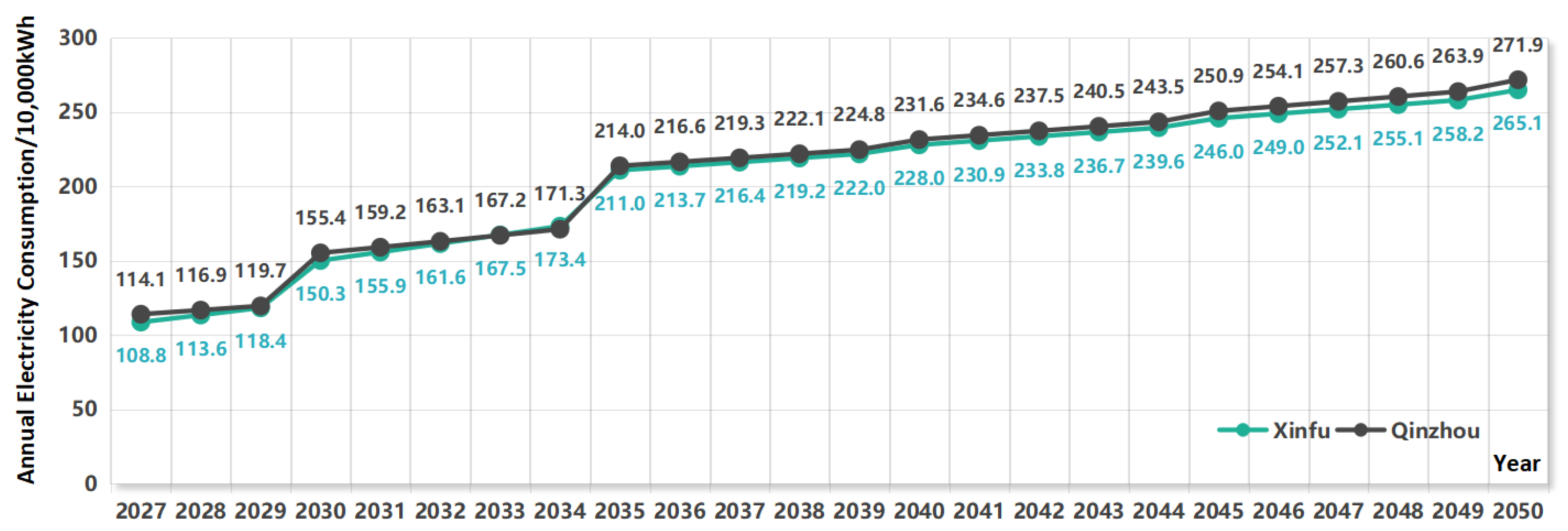

4.3. Mid-to-Long-Term Power Demand Forecast for Pinglu Canal

4.3.1. Hydropower Hub Electricity Usage

4.3.2. Service Area Power Demand

4.3.3. Shore Power System Power Demand

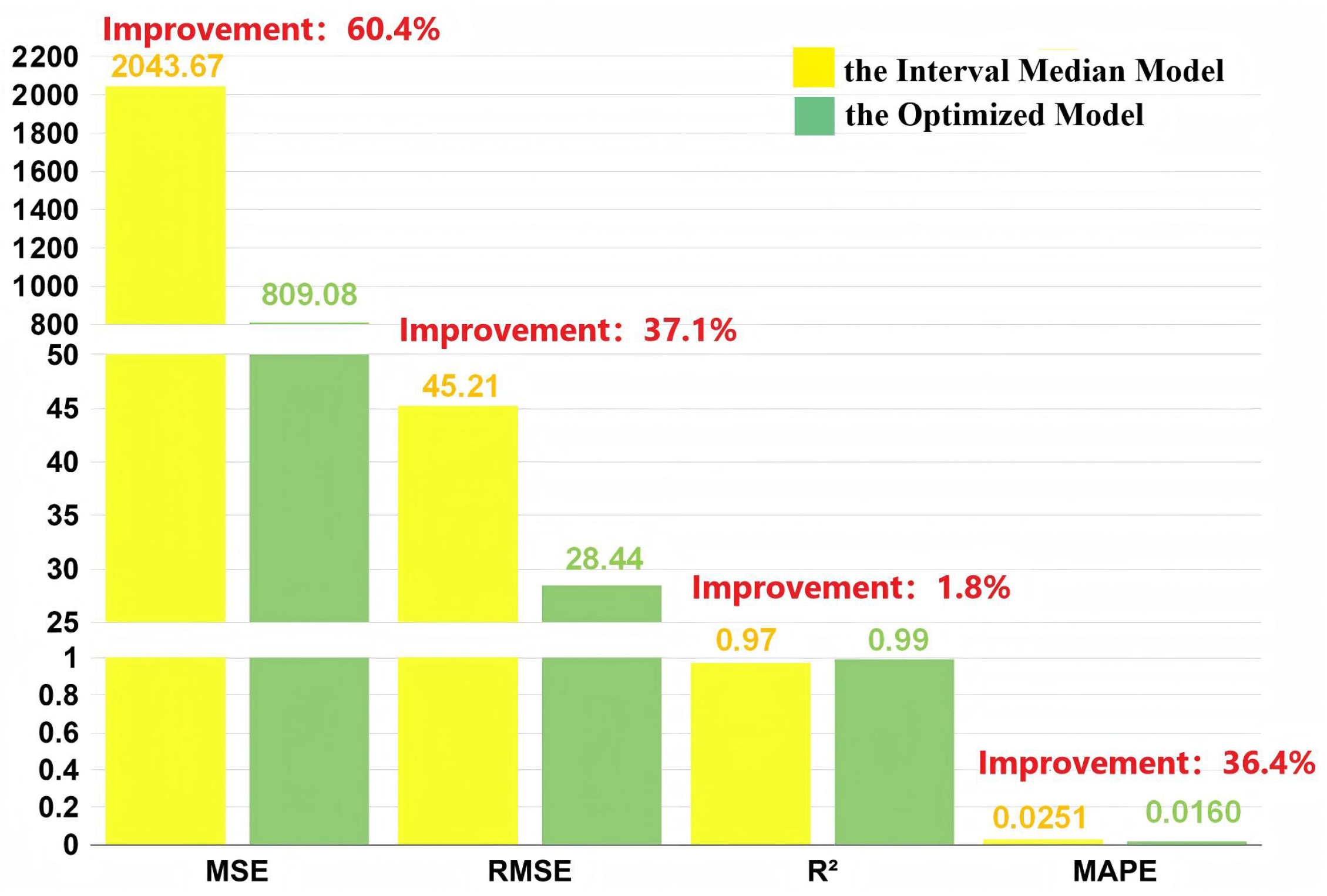

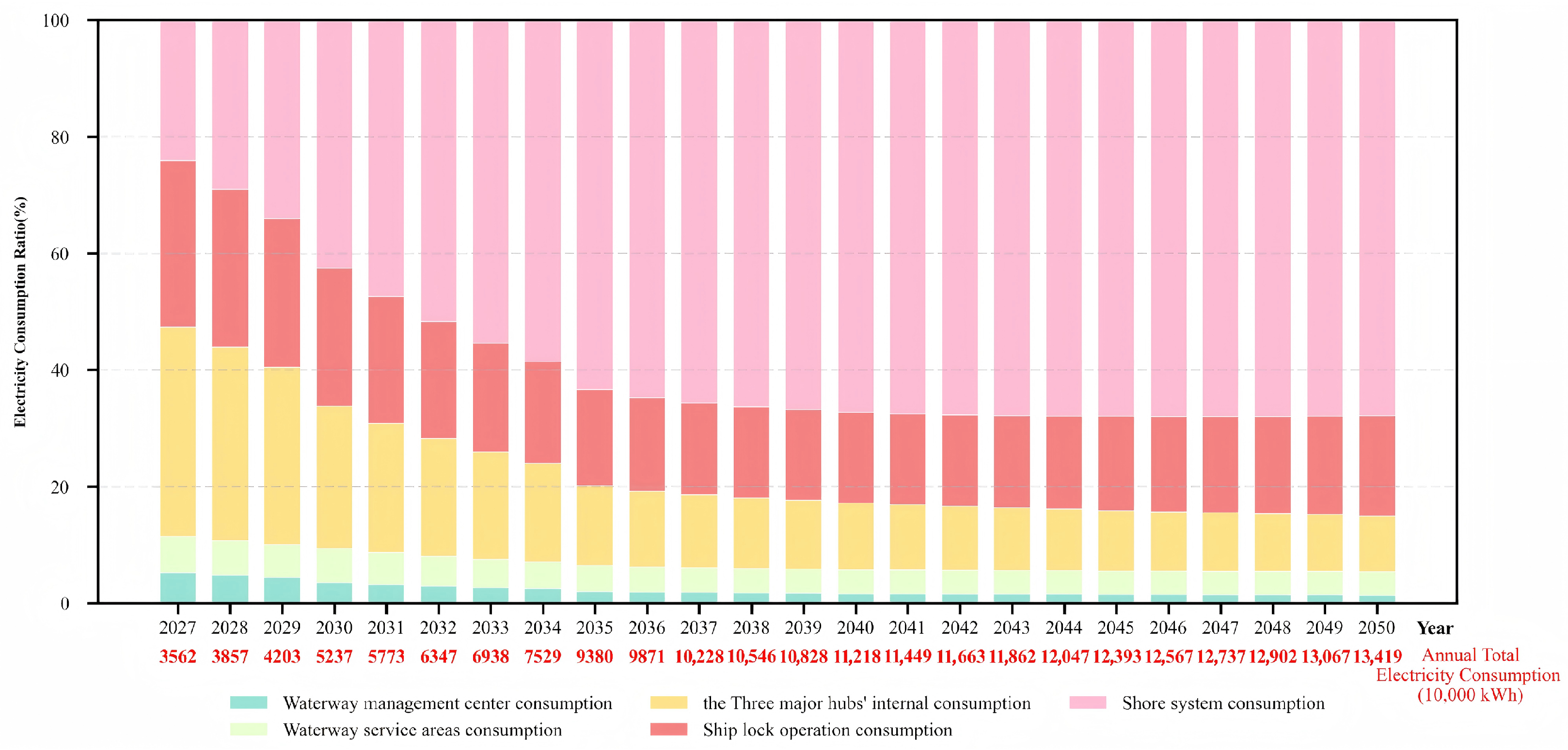

4.4. Analysis of Forecast Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 75 kW | 25 kW | ||

| 1 min | 0.5 min | ||

| 14.7 min | 15.6 min | ||

| 2 | 16 doors | ||

| L | 280 m | B | 34 m |

| Madao: 27.3 × 0.3 m Qishi: 26.3 × 0.3 m Qingnian: 10.0 × 0.3 m | 0.1 | ||

| 6 × 0.95 | 0 | ||

| Sanxia: 0.39; Xijiang: 0.43 | Sanxia: 1.5; Xijiang: 1.2 | ||

| Sanxia/Xijiang: 0.25 | Pinglu: 0.60 | ||

| 8900 tonnes | Monthly: 2.35 kW Annual: 25.2 kW |

Appendix B

References

- Zhu, M.Z. Current Situation Analysis and Development Countermeasures of Inland Waterway Logistics System. China Shipp. Wkly. 2023, 31, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- State Council. Outline for the National Comprehensive Three-Dimensional Transportation Network Plan; State Council: Beijing, China, 2021.

- State Council. The 14th Five-Year Plan for a Modern Integrated Transportation System; State Council: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Xing, P.X.; Pan, H.T. Canal Strategy in the New Era and Construction Practice of Pinglu Canal. Port Waterw. Eng. 2024, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.F.; Shen, J.Y. Medium-to-Long Term Load Forecasting Based on Least Squares State Estimation and Fuzzy Neural Network. Electr. Autom. 2024, 46, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Ruan, W.J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.Q. Research on Mid-Long Term Probabilistic Load Forecasting Method Based on Data Fusion. Power Demand Side Manag. 2024, 26, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.Q. Research on Medium-Long Term Power Load Forecasting in Ningxia Based on Coupled PSO-GPR Model. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.C.; Li, J.L.; Jiang, W.L.; Wang, R.Y.; Li, Z.P. Data-Driven Spatiotemporal Network for Urban Mid-Long Term Power Load Forecasting. Electr. Power 2025, 58, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Shen, B.; Lin, L.; Liu, D.; Yan, M.; Li, G. Residential Electricity Load Forecasting Based on Fuzzy Cluster Analysis and LSSVM with Optimization by the Fireworks Algorithm. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Research on Power Load Forecasting Based on Deep Learning. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Hefei, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chi, J.; Li, C. A Prosumer Power Prediction Method Based on Dynamic Segmented Curve Matching and Trend Feature Perception. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Shi, J.; Cheng, S.W. A decomposable multi-period mixing algorithm for long-term load forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 170, 110888. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.X. Application of Differential Grey Model in Medium-Long Term Power Load Forecasting. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Research and Application of Medium-Long Term Power Load Forecasting Technology. Master’s Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.X.; Huang, Q.Q.; Zhang, K.M.; Lin, Z.A.; Zhang, T.H.; Hu, X.T.; Liu, S.Y.; Jiang, C.X.; Yang, L.; Lin, Z.Z. Medium-long term load forecasting method considering industry correlation for power management. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.D.; Yu, J.Y.; Kong, X.Y. Mid-Long Term Load Forecasting Model Based on Dual Decomposition and Bidirectional LSTM. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 3418–3426. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Su, J.; Hong, Y.; Gong, P.; Zhu, D. Mid-to Long-Term Electric Load Forecasting Based on the EMD–Isomap–Adaboost Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaheh, Z.; Shabanzadeh, M. The effect of driver variables on the estimation of bivariate probability density of peak loads in long-term horizon. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.K. Research on Medium-Long Term Power Load Analysis and Forecasting Methods Under the New Normal. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Q.R.; Sun, F. Selection and Layout of Electrical Equipment in Hydropower Stations, 1st ed.; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, K.R.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.J. Construction of Green Comprehensive Service Zones Along the Jiangsu Section of Yangtze River. Shipp. Manag. 2023, 45, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.Y.; Cheng, L.; Lin, Y.; Wu, S.J.; Sun, C.P.; Gao, N. Planning Method for Charging Stations in Inland Ports Serving All-Electric Vessels. J. Shanghai Marit. Univ. 2025, 46, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport. General Design Code for Navigation Locks: JTS 180-2021; Ministry of Transport: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Mao, M. Configuration of Photovoltaic Systems for Expressway Service Areas Based on Electricity Load Analysis. Autom. Appl. 2023, 64, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zeng, M.L.; Xu, X.J. Development Status and Prospects of Electric-Powered Vessels in China. Shipp. Manag. 2025, 47, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.G.; Yuan, C.Q.; Zhai, H.; Yan, X.P. Development Status and Future Trends of Fujian’s Electric-Powered Vessel Industry. Strait Sci. 2024, 2, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.W. Research on Construction Strategy of Shore Power System for Ships in Inland Ports. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, R.N. Collaborative Optimization of Charging Station Location and Distribution Path for Electric Cargo Ships. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. Water Transport System and Intermodal Pattern of the New Western Land-Sea Corridor Anchored by Pinglu Canal. Hydro-Sci. Eng. 2025, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Historical Logic, Practical Significance, and Development Path of Industrial Growth in Pinglu Canal Economic Belt. Soc. Sci. 2024, 5, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.H.; Dong, H.Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, R.J.; Cao, L. Thoughts on Accelerating the Construction of Green Maritime Comprehensive Service Zones Along the Yangtze River Trunk Line. Technol. Econ. Chang. 2020, 4, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.N. Analysis of Navigation Obstruction and Research on Lock Toll-Based Congestion Mitigation at Three Gorges Hub. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.W.; Wang, Q.; Yu, J.Y. Countermeasures for Alleviating Ship Congestion at Three Gorges Hub. China Water Transp. 2024, 21, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- CCCC Water Transportation Consultants. Feasibility Study Report of Pinglu Canal Project; CCCC Water Transportation Consultants: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kaloev, M.; Krastev, G. Comprehensive Review of Benefits from the Use of Sparse Updates Techniques in Reinforcement Learning: Experimental Simulations in Complex Action Space Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES), Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 23–25 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, T.; Hou, M.; Giannelos, S.; Strbac, G. Decarbonisation of Data Centre Networks through Computing Power Migration. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Computer Communication and Artificial Intelligence (CCAI), Haikou, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 871–876. [Google Scholar]

| Type Tonnes | <2000 t | >2000 t |

|---|---|---|

| BEVs | 2400 | 8700 |

| HEVs | 1350 | 2400 |

| NEVs | 10 | 30 |

| Year | 2027–2030 | 2030–2035 | 2035–2040 | 2040–2045 | 2045–2050 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion | 3.0% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.3% | 3.4% | 3.5% |

| Node j | 1 | 2–5 | 6–7 | 8 | 9_ up | 9_ down |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35% | 0.10% | 0.15% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.55% | |

| /h | 4% | 10% | 8% | 10% | 4.6% | 10% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fu, J.; Gong, L.; Li, X.; Chen, B.; Lai, M.; Wang, N. Medium-to-Long-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Newly Constructed Canals Based on Navigation Traffic Volume Cascade Mapping. Sustainability 2026, 18, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010109

Fu J, Gong L, Li X, Chen B, Lai M, Wang N. Medium-to-Long-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Newly Constructed Canals Based on Navigation Traffic Volume Cascade Mapping. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Jing, Li Gong, Xiang Li, Biyun Chen, Min Lai, and Ni Wang. 2026. "Medium-to-Long-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Newly Constructed Canals Based on Navigation Traffic Volume Cascade Mapping" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010109

APA StyleFu, J., Gong, L., Li, X., Chen, B., Lai, M., & Wang, N. (2026). Medium-to-Long-Term Electricity Load Forecasting for Newly Constructed Canals Based on Navigation Traffic Volume Cascade Mapping. Sustainability, 18(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010109