3.5.1. Research Methods, Geographic Distribution, and Trends in Waste Sorting Studies

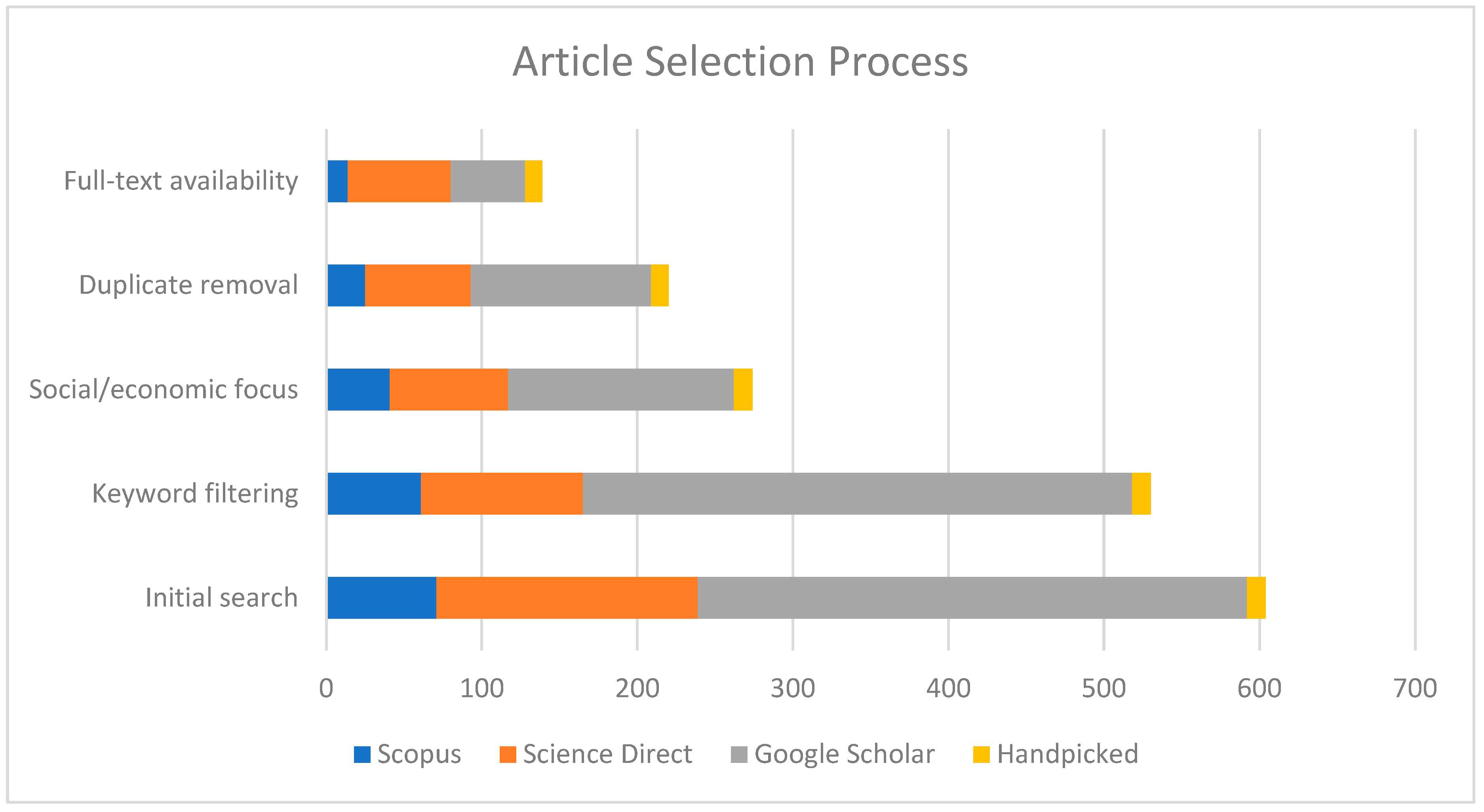

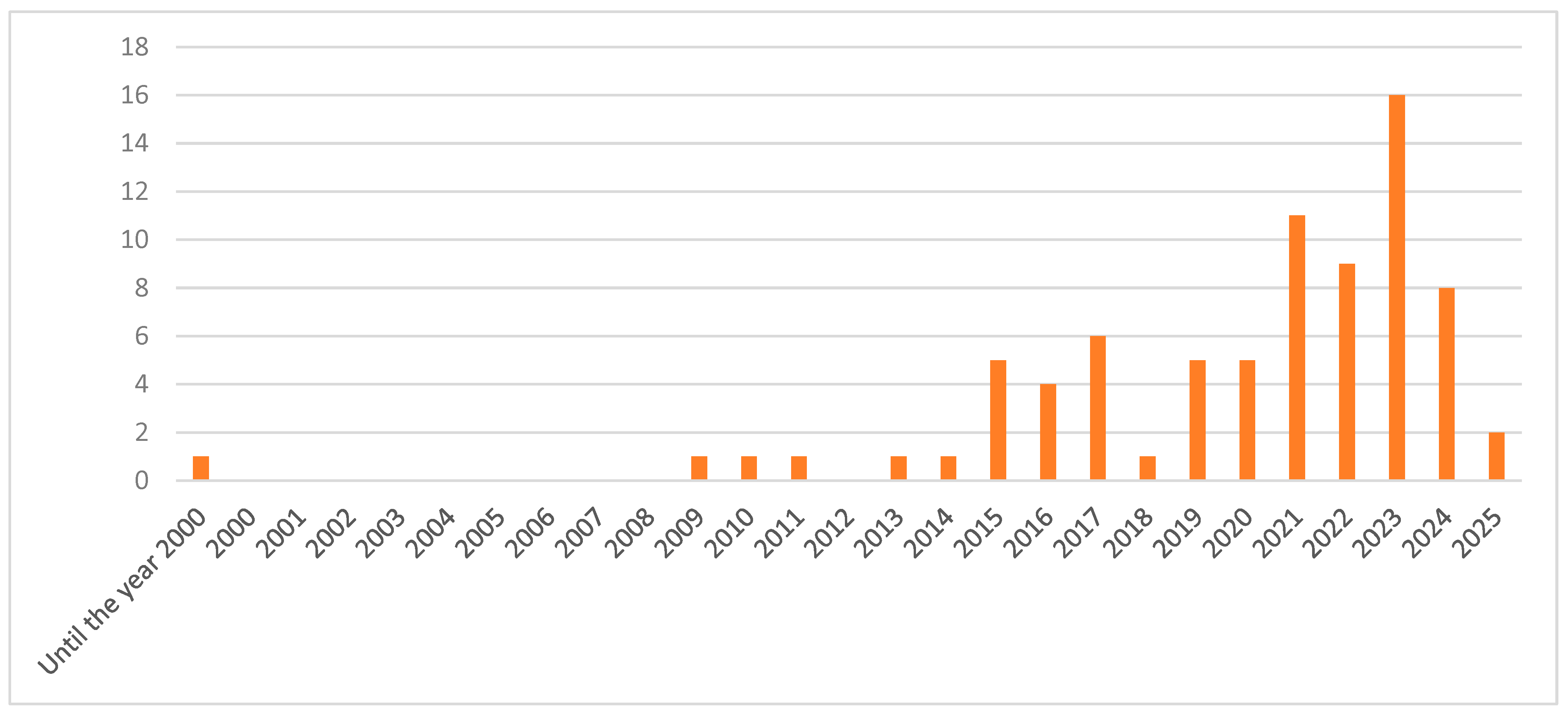

During the analysis, selected articles were analyzed according to the criteria selected in the previous section. The dynamics of the number of articles are presented in

Figure 2.

The analysis of articles by year reveals (

Figure 2) that the science focusing on waste sorting behavior was studied in only 8% of the articles reviewed before 2015. This indicates that waste sorting is an emerging field of study that has attracted more attention from academics in the last ten years. The increase in the number of articles published from 2015 and onwards shows an increasing awareness of the relevance of waste sorting in the context of sustainable development, following changes in policy and in the face of increasing waste management issues worldwide. It is important to note that the data for 2024 only includes publications up to March, as this study was conducted within the first quarter of the year. As a result, the lower number of articles for 2024 does not indicate a downward trend but, rather, reflects an incomplete dataset due to the ongoing publication cycle. Future analyses incorporating the full-year data may provide a clearer picture of whether the upward trend in waste sorting research continues.

Table 7 shows the distribution of articles by the name of the journal.

The analysis of the sources of publication of articles showed that as many as 42 articles (54%) are published in eight journals (

Table 7). The three main journals that usually provide information about the sorting behavior of consumers are the

Journal of Cleaner Production, Resources, Conservation and Recycling and

Waste Management. It is also important to note that eight articles were published during forums and conferences; this shows that the topic is relevant and presented immediately, as soon as the conclusions are received.

In

Table 8, the number of articles by the country where each study was conducted is shown.

As can be seen in

Table 8, the analysis of the countries to which the articles are addressed, most articles are devoted to the situation in China (37%). This is not surprising, since China has been strongly promoting waste sorting in major cities since 2017. Many articles are devoted to Scandinavia: 9%. The Czech Republic and Slovakia are allocated 8% of the articles. One article is dedicated to Lithuania, and another article, by Lithuanian authors, is dedicated to Sweden.

In

Table 9, the number of articles by data sample size is presented.

As

Table 9 shows, most articles that do not have a set sample size examine the information provided in statistical portals or do not even set such a goal. Also, several articles that analyzed the literature or used the crawling method were found here. Also included here is an Australian article in which the survey was conducted by a specially hired professional polling company who did not specify the sample size (they only provided the survey results). The authors usually used a small sample when conducting a controlled experiment, comparing the behavior of several groups under different conditions or conducting interviews (based on a prepared questionnaire). Average sampling is primarily used in smaller countries or electronic surveys. The large sample is mainly associated with the situation in China. Since sample sizes between 300 and 2000 individuals are the most prevalent, this is the most common practice that allows for generalizable conclusions.

In

Table 10, the number of articles by research method is given.

As can be seen in

Table 10, most articles (63%) in which the behavior of residents in waste sorting is studied are based on statistical studies. Even some of the articles that simulate a certain situation also use separately collected statistical data. This is completely understandable because, to understand the motives of the population’s behavior (which also differs according to territory, education, etc.), it is necessary to rely on the latest statistical studies, while generalized statistical information or information available on the Internet can distort the real facts (especially if the internal motives of the population are evaluated). Therefore, modeling is mainly used to assess external effects (mainly the influence of external policies).

When evaluating all the articles, it was found that only one, [

19], does not specify the method of data analysis. However, article [

19] is more intended to evaluate the theoretical replacement of a natural person by artificial intelligence in waste sorting (both at the point of generation and in sorting plants) and the possible economic benefits of such a replacement. The behavior of the population is not studied in this article.

3.5.2. Application of Behavioral Theories to Waste Sorting Practices

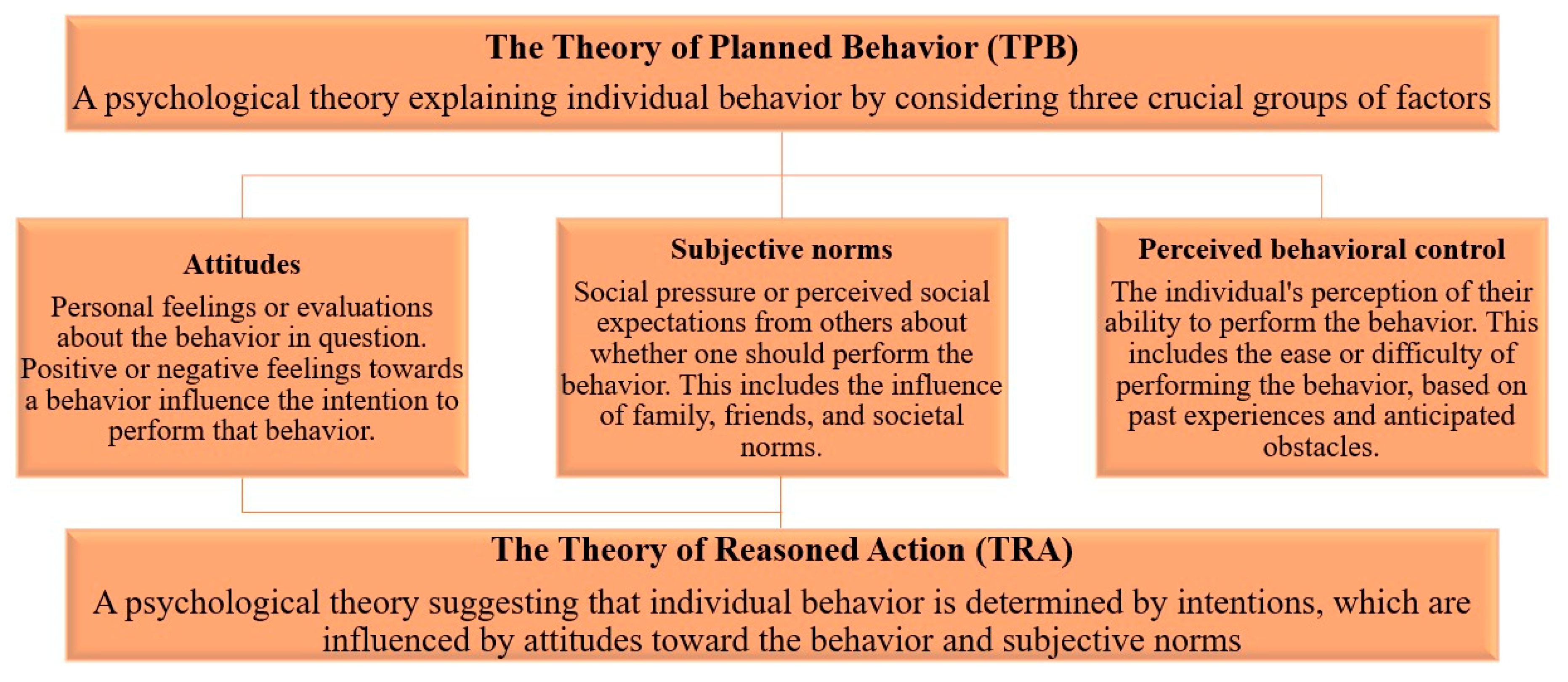

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) is behavioral science theory developed by Fishbein and Ajzen in 1975 [

20] to explain how attitudes and subjective norms affect behavioral intentions. This is because the TRA does not include the perceived behavioral control, which means that it is less useful in situations where external barriers such as infrastructure, financial, or policy constraints affect behavior. This limitation was addressed by Ajzen (1991) [

2] when he developed the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which included Perceived Behavioral Control as an extension of the original model. This enhancement helps the TPB to encompass a wider range of influences on behavior that range from within the individual (attitudes, social norms) to aspects outside the individual (waste collection, incentives, regulations). Although the TPB is acknowledged to be one of the best models for predicting waste sorting behavior, the TRA remains relevant for use when the decision to sort is mainly influenced by self-centered motivations and social pressures such as individual environmental responsibility, moral norms, or cultural norms. Hence, both theories offer different and complementary views on the same topic, with the TPB offering more specific and situational details, especially when analyzing the multi-factorial influences of psychological, economic, and policy-related factors in food waste classification. The relationship between the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is illustrated in

Figure 3, highlighting the key components that differentiate the two theories and their applicability to waste sorting behavior analysis.

Figure 3 shows that, while the TRA is based on attitudes and subjective norms, the TPB is an extension of the model, which includes perceived behavioral control, in situations where other factors such as infrastructure and regulations affect behavior. This visual representation shows that both theories are related, but the TPB offers a more general analytical framework, especially when investigating various influences of food waste sorting behavior, including psychological, economic, and policy factors.

Table 11 presents the classification of motivational factors of waste sorting based on external and internal influences, as identified in the reviewed articles.

As shown in

Table 11, external factors of waste sorting dominate in the reviewed articles, with 43% of the articles focusing on external influences. These include the following:

Internal factors of waste sorting are less frequently studied, but remain crucial. These include the following:

Environmental awareness: Individuals’ concern for the environment is a key motivator, especially in developed countries. For example, studies from the USA and Norway show that households with higher environmental awareness exhibit better sorting practices [

24,

25].

Social responsibility: A sense of moral obligation to contribute to sustainability often drives sorting behaviors [

20,

26].

Some articles explore the combined influence of external and internal factors of waste sorting, revealing the following:

Education can act as both an external (through public campaigns) and internal (through personal conviction) motivator [

24,

26].

Financial incentives are more effective when paired with educational initiatives that foster environmental awareness [

21,

23].

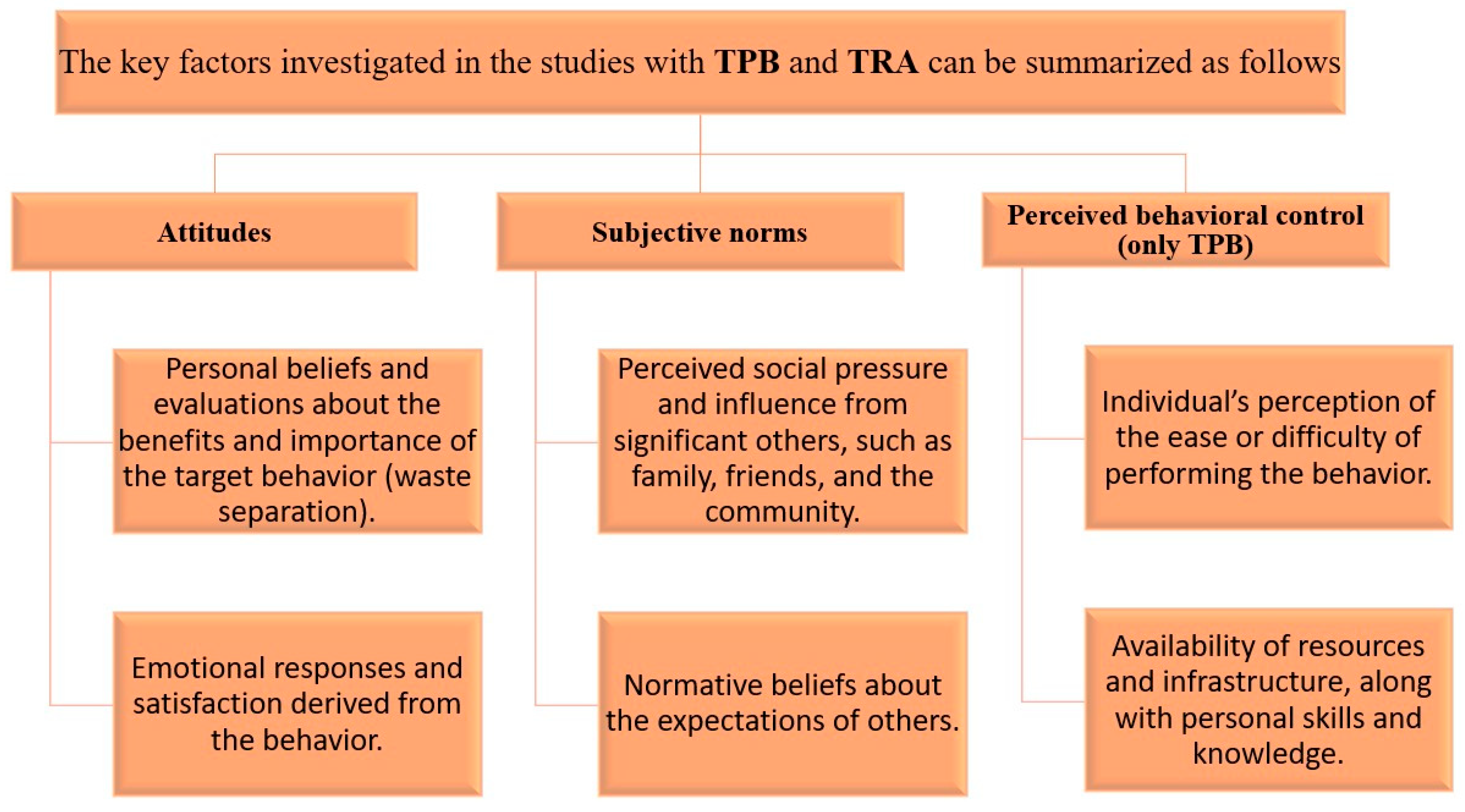

To further illustrate the application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) in waste sorting behavior research,

Figure 4 summarizes the key psychological and external factors influencing individuals’ waste separation decisions.

Figure 4 highlights three core elements: attitudes, which refer to personal beliefs and emotional responses towards waste separation; subjective norms, representing the influence of social expectations from family, friends, and the community; and perceived behavioral control (only in the TPB), which encompasses both the perceived ease or difficulty of sorting waste and the availability of necessary resources and infrastructure.

This structured representation reinforces the distinction between the TRA and the TPB, emphasizing how the TPB extends the TRA by considering external constraints, making it more applicable in contexts where infrastructure, policies, and economic incentives impact food waste sorting behaviors.

A significant portion of the articles (30%) do not directly study behavior, but instead focus on the following:

The population’s understanding of waste types [

24,

25].

The impact of educational campaigns on sorting knowledge [

23,

26].

This highlights a gap in understanding the interplay between knowledge and actual behavior, which requires further exploration. By analyzing the reviewed literature, this study identifies the following key gaps and trends in waste sorting research:

Dominance of external factors of waste sorting: While external influences are more frequently studied, the long-term sustainability of such measures requires integration with internal motivators [

21,

23].

Underexplored internal motivators: More studies are needed that examine the psychological and moral drivers of sorting behavior [

24,

25].

Regional variations: The effectiveness of motivators varies significantly across regions, emphasizing the need for localized strategies [

23,

26,

27].

TPB as a robust framework: The TPB remains the most comprehensive tool for studying waste sorting behaviors, but its integration with other models, such as Social Cognitive Theory, can provide deeper insights [

2,

25].

This analysis contributes to the field through the systematic categorization of motivational factors and an in-depth analysis of the TPB [

2] and the TRA [

20] within waste sorting research. The research shows that an interdisciplinary approach, including economic, psychological, and societal perspectives, is necessary for comprehensive understanding [

21,

24,

26].

The TRA and TPB remain central frameworks, while several other theories present different viewpoints. The Norm Activation Model (NAM) identifies personal moral norms as the main motivators of pro-environmental actions because it uses the awareness of consequences and personal responsibility to support sustainable waste management practices [

17]. Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory combines values with beliefs and personal norms because environmental concern emerges from altruistic and biospheric values [

28]. The models demonstrate strong explanatory power for voluntary actions that reduce food waste through ethical decision making.

Quantitative research methods, including multiple regression analysis structural equation modeling (SEM) and meta-analytic methods, allow food waste behavior research to evaluate psychological and socio-demographic causal relationships [

18]. Through Qualitative Comparative Analysis and textual analysis, researchers investigated individual and cultural waste management perceptions to discover hidden behavioral patterns that surveys and experiments sometimes fail to detect [

9].

Waste behavior research uses multiple theories and methods, despite the TPB remaining the most popular and comprehensive model to explain intention-driven actions [

29], including food waste sorting and reduction. This section investigates the TPB framework together with its application in analyzing household food waste behaviors.

3.5.3. Consumer Behavior and Motivations

Several key psychological, economic, and social factors [

10] that influence household food waste sorting behavior have been identified in the reviewed studies. Lack of awareness and inadequate infrastructure are the main barriers, especially in developing countries, as indicated by Aschemann-Witzel et al. (2019) [

30]. This means that there is a need to educate people and improve waste management systems to enhance participation. Berglund (2006) [

31] also established that economic incentives and personal environmental consciousness are significant motivators of food waste management, which means that financial rewards, penalties, and motivational campaigns play a significant role in determining sorting behavior. In addition, Perceived Behavioral Control, which is self-efficacy in performing a specific behavior, is a key determinant of participation [

16,

32] thus indicating that removing perceived barriers [

7,

33,

34], and increasing convenience may lead to higher compliance. Moreover, recent studies have established that public perception and psychological barriers are the major determinants of sorting behavior [

35,

36]. One of the significant reasons for non-participation in proper waste separation is the perceived difficulty of the process and the doubt about the effectiveness of the process [

37,

38]. Organizational recommendations include integrating environmental education into school curricula, as shown by Nguyen [

39], who stated that this will help develop sustainable habits among the next generation. Therefore, this study’s findings indicate that policy enforcement, economic incentives, awareness campaigns, and educational initiatives should be combined to ensure long-term change in food waste sorting behavior.

3.5.4. Strategies and Policies for Waste Management

Several reviewed studies also focus on the importance of policy compliance, individual motivation, and engineered waste management approaches as predictors of food waste recycling. The results show that direct personal contact through door-to-door delivery stands as a chief means of enhancing household participation in waste separation programs, according to both Bernstad [

40] and Dai [

41]. The results demonstrate that face-to-face contact and community-based interventions produce better behavioral outcomes than information-only campaigns, which call for more localized outreach strategies. Structured waste policies represent a critical component that ensures compliance with established regulations [

42,

43,

44]. Standardizing waste management through deposit practices at specific times and locations yields effective results in increasing recycling rates, according to Bian [

45]. Mandated policies and strict regulations are more effective in achieving higher participation rates than voluntary programs in specific settings. Sorting behavior is most influenced by awareness levels, convenience factors, and economic incentives, according to research by Bazargani [

46]. Without sufficient funding and precise policies and public involvement, waste sorting participation remains irregular, according to Čonková [

47,

48]. Policymakers need to direct their efforts toward establishing financial and infrastructural support that incentivizes households and businesses to maintain long-term compliance [

19,

49]. Govindan’s research [

50] reinforces the necessity of government intervention together with education programs to enhance policy-driven waste sorting behavior. Tian’s [

51] study, which compares waste sorting behavior in Chinese regions with and without sorting policies, demonstrates that strong government mandates produce higher compliance rates. This result strengthens the argument for holistic policy approaches that integrate forceful regulations with public awareness campaigns and financial motivations to establish widespread behavioral changes. The results indicate that personal engagement tactics, together with policy enforcement and financial rewards, are needed to enhance food waste sorting behaviors. More research should be conducted to evaluate the lasting effects of implemented policies [

52,

53] while studying how diverse socio-economic groups react to different regulatory methods.

3.5.5. Technological and Methodological Advances

The reviewed studies identify technological improvements in waste sorting methods and municipal infrastructure design as key factors that enhance waste sorting efficiency. Different locations and social contexts require specific effective waste separation methods and influencing factors which call for customized approaches to maximize participation [

54]. The results indicate that universal waste sorting approaches are not suitable because local economic status and physical infrastructure along with social customs must be considered by policymakers when developing waste management programs. Smart waste classification systems represent technological solutions that show growing relevance. Public willingness to participate in waste sorting depends heavily on their technological acceptance and their assessment of how easy the systems are to use [

55]. Without benefit-oriented features and an intuitive interface, system adoption remains low. Future initiatives should focus on making systems accessible [

56] and automated, while offering financial rewards to increase participation in technology-based waste sorting programs [

57]. Technological advancements alongside consumer eating practices [

58] directly affect the amount of waste generated. The waste generation data shows that fresh foods produce more waste than both frozen and ambient foods, which suggests that consumer education about food storage and purchase planning might help decrease waste [

59]. Waste reduction initiatives would benefit from policies which promote food preservation methods alongside improved supply chain practices. Waste sorting behavior is substantially influenced by the characteristics of physical infrastructure systems. Participation rates show substantial improvement when food waste collection points are closer to residents and sorting instructions are explicitly provided [

60]. The results show that urban planning measures must focus on easy access and straightforward waste disposal directions to achieve maximum efficiency. The results clearly demonstrate that waste sorting behaviors require simultaneous advancements in technological solutions along with motivational incentives [

61] and improved waste management infrastructure. Future studies should evaluate smart waste systems’ long-term performance alongside consumer behavior in food waste production and waste separation efficiency through optimal infrastructure designs.

3.5.6. Economic and Cost Analysis

Research papers highlight the quantitative impacts of waste sorting both in terms of costs and benefits. Berglund (2006) [

31] found that the most important factors for encouraging people to sort waste include personal motivation, financial rewards, and regulatory incentives. Despite municipalities perceiving financial incentives as additional costs, research shows that they scale back overall waste management costs and enhance environmental performance [

21]. The financial benefits of recyclable separation are verified through cost–benefit analyses of waste sorting programs that demonstrate reduced landfill expenses and better resource recovery practices [

62]. Evidence from Japan and China indicates that incorporating economic incentives such as penalty or reward systems leads to sustained participation and better environmental results [

63,

64]. Research has shown that coupon incentive systems enhance sorting rates and support efforts toward a sustainable economy in municipal waste management plans [

65]. Non-market advantages of waste sorting consist of environmental protection, decreased pollution, and positive impacts on population health despite not being derived from economic calculations [

66]. Municipalities should consider these indirect advantages when creating waste sorting policies since they advance economic and environmental sustainability in the long run [

67,

68]. The results clearly indicate that economic and financial incentives are the main motivators for people to practice waste sorting behavior [

69]. Further work should be directed towards the assessment of the long-term impact of financial incentives, the comparison of cost-effectiveness in different areas, and the search for new funding models for municipal waste management.

3.5.7. Community and Behavioral Insights

The research papers demonstrate that social norms, community engagement, and behavioral interventions play a key role in promoting waste sorting. Public awareness, along with accessibility and local context, acts as vital elements that determine household waste separation behaviors, according to Bergeron (2016) [

70] and Cantillo [

71]. The results indicate that generic waste sorting systems fail to work effectively because targeted policy and program interventions that match community needs and socio-economic conditions deliver better participation outcomes. Research demonstrates both social-influence- and education-based interventions as principal motivators for waste sorting behavior. Grytli and Birgen’s research [

72] reveals that educational programs, together with peer-led engagement initiatives and economic incentives [

73,

74], lead to improved compliance while fostering lasting behavioral changes. Household waste separation intentions strongly depend on two critical factors, which include social responsibility and perceived behavioral control, as well as normative and attitudinal elements [

75]. Though financial investment proves effective for waste management, research shows that monetary support alone fails to secure broad participation. A blend of economic rewards with community involvement along with focused messaging techniques produces enduring behavioral changes, according to research by Huang [

76]. TPB-based interventions demonstrate that attitudes, along with subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, drive household decisions to sort waste [

77]. The research results clearly show that incorporating social, economic, and educational strategies [

78] will enhance waste sorting participation rates. Future studies should evaluate community-led initiatives’ long-term effects while comparing waste sorting norms across cultures [

12] and developing behavioral interventions [

79,

80,

81] that transition intentions into actions [

8,

11].

3.5.8. Educational and Community-Based Interventions

The research findings highlight the necessity of educational programs and social rewards together with community involvement for improving waste sorting practices. The research demonstrates that game-based learning, together with interactive educational methods, serves as an effective method to strengthen long-term sorting practices. According to Hoffmann and Pfeiffer (2022) [

82], game-based learning produced substantial improvements in waste sorting practices. Public education campaigns that utilize interactive reward-based learning tools represent a potentially practical approach. Local authorities, alongside community-driven initiatives, demonstrate that they have a critical role in promoting waste separation practices. Jamal [

83] completed their study by showing that resident education programs, together with community involvement activities, boost waste sorting participation rates. Stričík, Bačová, and Čonková [

84] concluded that social norms alongside convenience stand as major motivators, which suggests that public recognition programs together with social campaigns should be implemented [

85]. Sorting facilities must be accessible and convenient to influence people’s behavior in waste management. According to Kamarudin and Jody [

86], awareness levels, together with accessibility and social norms, directly impact participation. The findings of Miliute-Plepiene and Plepys [

26] reveal that enhanced food waste sorting practices produce better overall waste management results [

13,

15], which supports the necessity of supportive infrastructure and policy actions. The research demonstrates that waste sorting programs must combine educational components [

87] with community activities [

88] and improved infrastructure to achieve behavioral change [

14,

89]. Future research needs to analyze the durability of gamified learning approaches and digital engagement methods while evaluating community-led initiative scalability and investigating how convenience, alongside social norms and policy frameworks, influences sustainable waste management practices [

90,

91].

3.5.9. Recommendations for Further Studies

To improve the current understanding and effectiveness of food waste sorting behaviors, future work should examine several important areas. Another important way to explore this topic is to investigate psychological and behavioral aspects more extensively. Even though the TPB is the most popular framework, other models, such as the VBN theory and the SCT, should also be employed to understand the role of moral reasoning, social norms, and community identification in waste sorting behavior. Longitudinal designs could also help in understanding the lasting impact of educational campaigns and incentive programs, and whether people keep on practicing waste sorting over time and whether they need to be reminded to do so. Another important subject for future work is economic incentives and financial means. Studies should also look at the cost-effectiveness of different incentive-based interventions like pay-as-you-throw, deposit–refund, and tax reduction. International comparisons of countries with different waste management policies (mandatory sorting laws vs. voluntary incentive-based arrangements) may help to identify which approaches foster greater engagement and compliance. Moreover, the research should involve the analysis of how socio-economic factors affect the response to economic incentives so that the financial measures are equitable and effective for all the target groups. Another promising area of further research is related to technological advancements. The use of artificial intelligence in waste sorting, the use of the Internet of Things in smart bins, and the use of mobile applications can enhance the sorting efficiency and the level of public engagement. It would be beneficial to investigate the effects of computerized nudges, game-based mobile applications, and social media interventions on waste sorting behavior. Furthermore, a comparative analysis of automated waste management systems across countries can help in identifying the best practices for the implementation of these technologies in urban and rural settings. Another important direction for further research is the cultural and regional differences in waste sorting behavior. Most of the existing research has been conducted in developed countries, while the understanding of how waste sorting practices develop in low- and middle-income countries with different infrastructure, policy compliance, and social norms is lacking. Cross-cultural research can provide valuable lessons on how community engagement, traditional waste management practices, and collective identity influence sorting behaviors. This would give a full picture of how to design waste management policies for different cultural settings. More work needs to be completed to assess the impact of policy interventions and community engagement strategies. Those countries that have recently enacted mandatory sorting regulations should be observed in the long run to determine the effects of legislation. Moreover, studies should look at the role of local governments, Non-Governmental Organizations, and community-based organizations in enhancing the participation of the public. Randomized experiments could provide valuable information on the most appropriate kinds of communication strategies, such as fear appeals, social norm messaging, or positive reinforcement, that can be used to promote waste sorting. One of the most common problems in waste sorting research is the intention–action gap, where people who have pro-environmental beliefs do not necessarily practice what they preach in terms of waste management. Future work should also address the reasons why people fail to act on their intentions, such as inconvenience, ignorance, skepticism towards waste management policies, and barriers. Experimental field studies can offer important lessons as to how this gap can be closed through specific interventions. Lastly, future work should build on household food waste sorting and explore institutional and commercial food waste segregation. However, while most research concentration is on residential waste management, food waste is also produced in schools, universities, offices, and the food service industry. Studying waste management practices in these contexts will offer a more complete and applicable perspective on how waste management policies can be implemented in various settings.