The Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Outdoor Brand Attitude and Loyalty: A Bifactor Structural Model Approach with a Moderator of Outdoor Involvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Green Marketing and the Marketing Mix (4Ps)

2.1.1. Green Product

2.1.2. Green Price

2.1.3. Green Place

2.1.4. Green Promotion

2.2. Signaling Theory in Green Marketing and Brand Attitude

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Outdoor Activity Involvement

2.4. Brand Attitude and Brand Loyalty

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Participants

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation

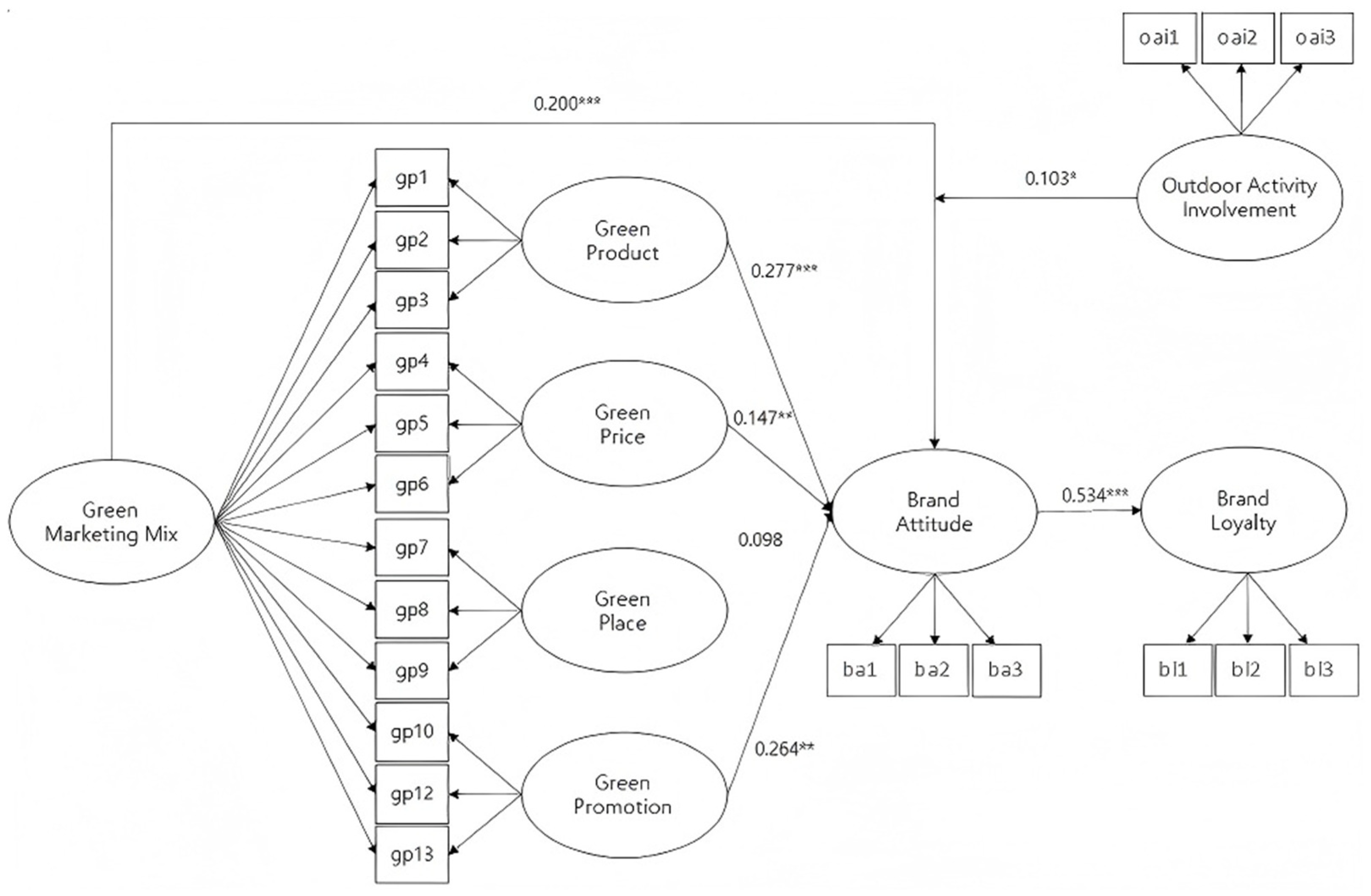

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Impact of the Green Marketing Mix on Brand Attitude

5.2. Moderating Role of Outdoor Activity Involvement

5.3. Impact of Brand Attitude on Brand Loyalty

5.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Myers, S.S.; Patz, J.A. Emerging threats to human health from global environmental change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson Coon, J.; Boddy, K.; Stein, K.; Whear, R.; Barton, J.; Depledge, M.H. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beery, T.; Olsson, M.R.; Vitestam, M. COVID-19 and outdoor recreation management: Increased participation, connection to nature, and a look to climate adaptation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 36, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, K.; John Sinclair, A.; Diduck, A. Stakeholder engagement in sustainable adventure tourism development in the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, T. An analysis of the South African adventure tourism industry. Anatolia 2018, 29, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J. Development of outdoor recreation in Beijing, China between 1990 and 2010. Cities 2014, 37, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024 Outdoor Participation Trends Report—Outdoor Industry Association. Available online: https://outdoorindustry.org/article/2024-outdoor-participation-trends-report/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Outdoor Products Market Size, Growth Analysis Report [2032]. Available online: https://www.astuteanalytica.com/industry-report/outdoor-products-market (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Outdoor Products Market Growth: 2024–2032 Forecast. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/escape-ordinary-dive-adventure-premium-outdoor-products-o32ic (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- US Outdoor Recreation Market Report 2023|Trends & Analysis. Available online: https://store.mintel.com/report/us-outdoor-recreation-market-report (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Zaman, K. Which generation is more environmental consciousness? A comparative study of Generation Z & Millennial to predict effect of digital ads on green buying decisions. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Marketing to Gen Z Consumer Report 2024|Mintel Store. Available online: https://store.mintel.com/report/us-marketing-to-gen-z-market-report (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Dzurik, M.; Gilbride, A.; Gierke, D. Purpose Beyond Profit: Sustainability in the Outdoor Industry. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gossen, M.; Kropfeld, M.I. “Choose nature. Buy less.” Exploring sufficiency-oriented marketing and consumption practices in the outdoor industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, D.S.; Vidon, E.S. Purchasing protection: Outdoor companies and the authentication of technology use in nature-based tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Sustainability Top Priority for One in Five Consumers—Better Retailing. Available online: https://www.betterretailing.com/environmental-sustainability-top-priority-for-one-in-five-consumers/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Chen, S.; Chen, Y. An empirical analysis of green marketing—A case study of government’s plastic reduction policy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Rev. 2020, 3, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyak, D.; Grigoliene, R. Analysis of the conceptual frameworks of green marketing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.K.; Wu, W.Y.; Pham, T.T. Examining the moderating effects of green marketing and green psychological benefits on customers’ green attitude, value and purchase intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, T.O. Green marketing: A marketing mix concept. Int. J. Electr. Electron. Comput. 2019, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green marketing orientation: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, O. The Effect of Brand Values on Consumer Behavior: The Case of Outdoor Clothing Industry. Bachelor’s Thesis, Turku University of Applied Sciences, Turku, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, M.; Hovemann, G. The circular economy concept in the outdoor sporting goods industry: Challenges and enablers of current practices among brands and retailers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Lee, H.; Li, A. Preferred product attributes for sustainable outdoor apparel: A conjoint analysis approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwipamurti, I.G.A.N.; Mawardi, M.K.; Nuralam, I.P. The effect of green marketing on brand image and purchase decision (study on consumer of Starbucks Café Ubud, Gianyar Bali). J. Adm. Bisnis. 2018, 61, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Alhaddad, A. A structural model of the relationships between brand image, brand trust and brand loyalty. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 5, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J.; Obermiller, C. The elaboration likelihood model: Limitations and extensions in marketing. Adv. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 420–425. [Google Scholar]

- Martensen, A.; Mouritsen, J. Using the power of word-of-mouth to leverage the effect of marketing activities on consumer responses. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2016, 27, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Patel, J.; Modi, A.; Paul, J. Pro-environmental behavior and socio-demographic factors in an emerging market. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 6, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, J.R.K.; Uppal, A.; Sharma, A.; Dekimpe, M.G. A global perspective on the marketing mix across time and space. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2022, 39, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Gangwar, V.P.; Dash, G. Green marketing strategies, environmental attitude, and green buying intention: A multi-group analysis in an emerging economy context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Tripathi, D.M.; Srivastava, U.; Yadav, P.K. Green marketing—Emerging dimensions. J. Bus. Excell. 2011, 2, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dargusch, P.; Ward, A. Understanding corporate social responsibility with the integration of supply chain management in outdoor apparel manufacturers in North America and Australia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2010, 3, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Brent Jackson, S.; Stevenson, K.T.; Larson, L.R.; Nils Peterson, M.; Seekamp, E. Outdoor activity participation improves adolescents’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Gokarn, S. Green marketing: A means for sustainable development. J. Arts Sci. Commer. 2013, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Braimah, M. Green brand awareness and customer purchase intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2015, 5, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Lavuri, R.; Bilal, M.; Hameed, I.; Byun, J. Exploring the roles of green marketing tools and green motives on green purchase intention in sustainable tourism destinations: A cross-cultural study. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Khosla, R. Examination of Environmental Beliefs and Its Impact on the Influence of Price, Quality and Demographic Characteristics with Respect to Green Purchase Intention. J. Target. Meas. 2007, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranee, C. Marketing Ethical Implication and Social Responsibility. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2010, 2, 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bathmanathan, V.; Rajadurai, J. Redefining the value proposition through green promotions and green corporate image in the era of Industrial Revolution 4.0: A study of Gen Y green consumers in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2019, 22, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch, T.R.; Awan, T.M.; Malik, H.A.; Fatima, T. Unboxing the green box: An empirical assessment of buying behavior of green products. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 690–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A. “Greening” the marketing mix: Do firms do it and does it pay off? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, A.C. Green marketing and consumer behavior: An analytical literature review and marketing implications. Bus. Econ. Res. 2024, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggelund, P.; Berg Hersdal, M.; Hunnes, J.A. Navigating the green path: The Scandinavian outdoor industry’s quest for sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2268336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, S.; Milfeld, T. Sustainability advertising: Literature review and framework for future research. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, M.; Muhs, C.; Neves, M.C.; Engel, L.; Cardoso, L.F. Green marketing: A case study of the outdoor apparel brand Patagonia. Responsib. Sustain. 2023, 8, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurjaman, K. Overview of the application of the concept of green marketing in environment conservation. Eqien-J. Ekon. Bisnis. 2022, 11, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A. Green marketing, public policy and managerial strategies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2002, 11, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B. The impact of green marketing mix elements on green customer based brand equity in an emerging market. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2023, 15, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Chaudhary, M. Take a chance at making the world a better place: A paradigm for sustainable development through green marketing. Int. J. Multidiscip. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maksudunov, A.; Avci, M. The color of the future in marketing is green. In Contemporary Issues in Strategic Marketing; Istanbul University Press: Istanbul, Turkey, 2020; pp. 225–254. [Google Scholar]

- Shamdasani, P.; Chon-Lin, G.O.; Richmond, D. Exploring green consumers in an oriental culture: Role of personal and marketing mix factors. Adv. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J.; Books, N.B. Green marketing: Opportunity for innovation. J. Sustain. Prod. Des. 1998, 60, 136–667. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Green Consumption: Life-Politics, Risk and Contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C. How Green Marketing Works: Practices, Materialities, and Images. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Feeling Ambivalent about Going Green: Implications for Green Advertising Processing. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, A.; Strutton, D. Marketing Mix Strategies for Closing the Gap between Green Consumers’ pro-Environmental Beliefs and Behaviors. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaili, M.; Fazeli, S.F. Surveying of Importance of Green Marketing Compared Purchase Budget and Preferred Brand When Buying by AHP Method. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseculeratne, D.; Yazdanifard, R. How Green Marketing Can Create a Sustainable Competitive Advantage for a Business. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abzari, M.; Safari Shad, F.; Akbar Abedi Sharbiyani, A.; Parvareshi Morad, A. Studying the effect of green marketing mix on market share increase. Europ. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio, J. Creating Sustainable Brands: How the Green 4 Ps Influence Consumers’ Attitudes Toward Brands. Honors Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, E. The Outdoor Apparel Industry: Measuring the Premium for Sustainability with a Hedonic Pricing Model. Senior Thesis, Claremont College, Claremont, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, A.; Menon, A. Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: The emergence of corporate environmentalism as market strategy. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuprina, N.; Pashkevich, K.; Kolosnichenko, O.; Scliarenko, N.; Davydenko, I.; Kokorina, G. Eco-oriented functional characteristics of outdoor clothing as an update to its design solutions. New Des. Ideas. 2023, 7, 593–606. [Google Scholar]

- Eneizan, B.M.; Abd Wahab, K.; Zainon, M.S.; Obaid, T.F. Effects of green marketing strategy on the financial and non-financial performance of firms: A conceptual paper. Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. (Oman Chapter) 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikiene, D.; Qadir, H.; Streimikis, J. Effect of Green Marketing Mix, Green Customer Value, and Attitude on Green Purchase Intention: Evidence from the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 11473–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Jan, S.; Ali, F.; Nadeem, A.; Raza, W. Impact of green marketing mix (4Ps) on firm performance: Insights from industrial sector Peshawar, Pakistan. Sarhad J. Manag. Sci. 2019, 5, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. Output sector munificence and supplier control in industrial channels of distribution: A contingency approach. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukonza, C.; Swarts, I. The Influence of Green Marketing Strategies on Business Performance and Corporate Image in the Retail Sector. Bus Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok Uikey, A.; Baber, R.; Baber Assistant Professor, R. Exploring the Factors That Foster Green Brand Loyalty: The Role of Green Transparency, Green Perceived Value, Green Brand Trust and Self-Brand Connection. Community Commun. Amity Sch. Commun. 2023, 18, 2456–9011. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Yang, D.; Liu, S.; Mei, Q. The impact of green supply chain management on enterprise environmental performance: A meta-analysis. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2023, 17, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.D.; Kumar, V.V.R. Three decades of green advertising—A review of literature and bibliometric analysis. Benchmarking 2020, 28, 1934–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, S.S.; Behe, B.K. Retail promotion and advertising in the green industry: An overview and exploration of the use of digital advertising. HortTechnology 2017, 27, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Tang, Y.; Qing, P.; Li, H.; Razzaq, A. Donation or discount: Effect of promotion mode on green consumption behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behavior towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, F.; Föhl, U.; Walter, N.; Demmer, V. Green or social? An analysis of environmental and social sustainability advertising and its impact on brand personality, credibility and attitude. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jang, L.; Chen, C. Assessing the role of involvement as a mediator of allocentrist responses to advertising and normative influence. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.C. Sustainable Trailblazing: A Comprehensive Analysis of Patagonia’s Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives and Their Ethical Implications. Master’s Thesis, Belhaven University, Jackson, MS, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Z.A.; Tariq, M.I.; Paul, J.; Naqvi, S.A.; Hallo, L. Signaling theory and its relevance in international marketing: A systematic review and future research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2024, 41, 514–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.; Kim, N.L. Green as the New Status Symbol: Examining Green Signaling Effects among Gen Z and Millennial Consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2024, 28, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlanova, T.; Benbunan-Fich, R.; Lang, G. The Role of External and Internal Signals in E-Commerce. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 87, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G.J. The economics of information. J. Polit. Econ. 1961, 69, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, D.D.; Gibbons, P. The stock market reaction to the hiring of management consultants: A signalling theory approach. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Reutzel, C.R.; DesJardine, M.R.; Zhou, Y.S. Signaling theory: State of the theory and its future. J. Manag. 2025, 51, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, J.; Mizerski, D.; Soh, H. Self-Congruity, Brand Attitude, and Brand Loyalty: A Study on Luxury Brands. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Ketchen, D.J.; Slater, S.F. Toward a “Theoretical Toolbox” for Sustainability Research in Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signaling. In Uncertainty in Economics, 1st ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.W.; Chen, Y.S.; Yeh, Y.L.; Li, H.X. Sustainable Consumption Models for Customers: Investigating the Significant Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior from the Perspective of Information Asymmetry. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2021, 64, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, E.; Wahid, N.A. Investigation of Green Marketing Tools’ Effect on Consumers’ Purchase Behavior. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2011, 12, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful Consumption: A Customer-Centric Approach to Sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, D.; Head, M.; Lim, E.; Stibe, A. Using the Elaboration Likelihood Model to Examine Online Persuasion through Website Design. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogah, A.I.; Abutu, D.O. Theoretical analysis on persuasive communication in advertising and its application in marketing communication. EJOTMAS Ekpoma J. Theatre Media Arts. 2022, 8, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culén, A.L.; Srivastava, S. Gen MZ Toward Sustainable Fashion Practices—Alternative Services and Business Models. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena, N.S.; Thaichon, P.; Quach, S.; Razzaq, A.; Behl, A. The Persuasion Effects of Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) Video Advertisements: A Conceptual Review. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M.T.; Benoit, W.L.; Tschida, D.A. Testing the Mediating Role of Cognitive Responses in the Elaboration Likelihood Model. Commun. Stud. 2001, 52, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S. Do Brands Talk Differently? An Examination of Product Category Involvement of Elaboration Likelihood Model in Facebook. Korean J. Advert. 2014, 3, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J. Central or Peripheral? Cognition Elaboration Cues’ Effect on Users’ Continuance Intention of Mobile Health Applications in the Developing Markets. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 116, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, P.J.; Kerr, G.; Schultz, D.E.; McColl, R.; Pals, H. The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Review, Critique and Research Agenda. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 2033–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revision, and application to advertising. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, K. Modeling the Effects of Green Advertising on Brand Image: Investigating the Moderating Effects of Product Involvement Using Structural Equation. J. Glob. Mark. 2015, 28, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlister, A.R.; Bargh, D. Dissuasion: The Elaboration Likelihood Model and Young Children. Young Consum. 2016, 17, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Jasper, C.R. Processing of apparel advertisements: Application and extension of elaboration likelihood model. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2006, 24, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.M. Cultivated Positive Emotions Inspire Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, N.H. Elaboration likelihood model in consumer research: A review. Proc. Natl. Sci. Counc. 2001, 11, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Spreng, R.A. How Does Motivation Moderate the Impact of Central and Peripheral Processing on Brand Attitudes and Intentions? J. Consum. Res. 1992, 18, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, J.J. Human Baristas and Robot Baristas: How Does Brand Experience Affect Brand Satisfaction, Brand Attitude, Brand Attachment, and Brand Loyalty? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.S.; Basu, K. Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some Antecedents and Outcomes of Brand Love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, A.H.; Park, H.Y. The effect of airline’s professional models on brand loyalty: Focusing on mediating effect of brand attitude. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldinger, A.L.; Rubinson, J. Brand loyalty: The link between attitude and behavior. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Shen, Z. Sensory Brand Experience and Brand Loyalty: Mediators and Gender Differences. Acta Psychol. 2024, 244, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.N.; Hu, C.; Lin, M.C.; Tsai, T.I.; Xiao, Q. Brand Knowledge and Non-Financial Brand Performance in the Green Restaurants: Mediating Effect of Brand Attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjani, S.; Perdhana, M.S. Green marketing mix effects on consumers’ purchase decision: A literature study. Diponegoro J. Manag. 2021, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, A.S.; Sari, N.P.; Khairi, A. The relationship between green marketing mix and purchasing decisions: The role of brand image as mediator. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of Management and Business (ICoMB 2022), Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 24–25 September 2022; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Skackauskiene, I.; Díaz-Meneses, G. Measuring Green Marketing: Scale Development and Validation. Energies 2022, 15, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimanfar, S.; Hatam Nezhad, K. Investigating the Mixed Effect of Green Marketing on the Decision of Green Buying Consumers (Case Study: Consumers of Mihan Company’s Dairy Products in Arak). Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2022, 6, em0178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munamba, R.; Nuangjamnong, C. The Impact of Green Marketing Mix and Attitude Towards the Green Purchase Intention Among Generation Y Consumers. Master’s Thesis, Assumption University of Thailand, Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mushi, H.M. Moderating Role of Green Innovation between Sustainability Strategies and Firm Performance in Tanzania. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2440624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kima, B.Y.; Hanb, Y.H.; Yangc, C.H. The effect of brand personality perceived by outdoor ware consumers on brand attitude and brand loyalty. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2019, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nayeem, T.; Murshed, F.; Dwivedi, A. Brand Experience and Brand Attitude: Examining a Credibility-Based Mechanism. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ko, Y.J. The Impact of Virtual Reality (VR) Technology on Sport Spectators’ Flow Experience and Satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.L.; Gagné, M.; Morin, A.J.S.; Forest, J. Using Bifactor Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling to Test for a Continuum Structure of Motivation. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2638–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.S.; Mobley, W.H. Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Moosbrugger, H. Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika 2000, 65, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, D.; Pokhrel, L. Green Brand Positioning and Attitude towards Green Brands: Mediating Role of Green Brand Knowledge among Green Consumers in the Kathmandu Valley. Quest J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdikhani, R.; Valmohammadi, C. The Effects of Green Brand Equity on Green Word of Mouth: The Mediating Roles of Three Green Factors. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, S.; Dharmmesta, B.S.; Purwanto, B.M. Model of Consumer Attitude in the Activity of Cause-Related Marketing. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Xiaoling, G.; Sherwani, M.; Ali, A. Antecedents of Consumers’ Halal Brand Purchase Intention: An Integrated Approach. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Hawkins, D.I. Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Young, L.C.; Wilkinson, I. The Nature and Role of Different Types of Commitment in Inter-Firm Relationship Cooperation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 30, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, J. Sustainability Issues and Strategies in the Outdoor Apparel Brand Industry. Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Fang, S.; Cheng, Y. Is Traditional Marketing Mix Still Suitable for Hotel Banquets? An Empirical Study of Banquet Marketing in Five-Star Hotels. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Marketing: A New Perspective with 4 P’s of Marketing. Academia. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/6350422/Green_Marketing_A_New_Perspective_with_4_Ps_of_Marketing (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Hanssens, D.M.; Pauwels, K.H.; Srinivasan, S.; Vanhuele, M.; Yildirim, G. Consumer Attitude Metrics for Guiding Marketing Mix Decisions. Mark. Sci. 2014, 33, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisdayanti, K.; Widodo, A. Green Marketing and Purchase Intention of Green Product: The Role of Environmental Awareness. J. Manag. Strateg. Appl. Bus. 2022, 5, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifollahi, N. Analysis of the Effect of Green Marketing Mix and Green Brand Attitude on Urban Tourism with the Mediating Role of Green Intellectual Capital: The Study Case of Ardabil City Tourists. J. Urban Tour. 2024, 11, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.; Jose, A. The influence of green marketing on brand equity—Analyzing the 4 P’s. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Sadiq, B.; Bashir, T.; Mahmood, H.; Rasool, Y. Investigating the Impact of Green Marketing Components on Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Brand Image and Brand Trust. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Greening Retail: An Indian Experience. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.; Ali, N.A. The Impact of Green Marketing Strategy on the Firm’s Performance in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.Y.; Wang, C.N. Perceived Risk Influence on Dual-Route Information Adoption Processes on Travel Websites. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Lee, J.W. Organizational Usage of Social Media for Corporate Reputation Management. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H. The Effects of City Brand Image on City Brand Recognition and City Loyalty. Int. J. Intell. Diff. Bus. 2018, 9, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Reinartz, W.J.; Kumar, V. On the profitability of long-life customers in a noncontractual setting: An empirical investigation and implications for marketing. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors and Items | λ | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Product | 0.891 | 0.720 | |

| The outdoor brand I purchased produces eco-friendly products. | 0.842 | ||

| The outdoor brand I purchased strives to improve design and quality to create eco-friendly products. | 0.887 | ||

| The outdoor brand I purchased plays a leading role in introducing eco-friendly products to the market. | 0.820 | ||

| Green Price | 0.868 | 0.687 | |

| The outdoor brand I purchased is more expensive than other brands because it pursues eco-friendly and sustainable values. | 0.797 | ||

| The price of the outdoor brand I purchased reflects its environmental benefits. | 0.835 | ||

| The eco-friendly features of the outdoor brand I purchased enhance its market value. | 0.853 | ||

| Green Place | 0.904 | 0.757 | |

| The outdoor brand I purchased considers environmental issues in its distribution process. | 0.872 | ||

| The stores selling the outdoor brand I purchased are themselves environmentally friendly. | 0.867 | ||

| The outdoor brand I purchased has an eco-friendly transportation system. | 0.869 | ||

| Green Promotion | 0.918 | 0.789 | |

| The outdoor brand I purchased promotes a healthy lifestyle using eco-friendly products. | 0.880 | ||

| The advertisements of the outdoor brand I purchased include eco-friendly messages. | 0.877 | ||

| The outdoor brand I purchased presents itself as a company that fulfills its environmental responsibilities. | 0.908 | ||

| Brand Attitude | 0.910 | 0.770 | |

| Overall, my feelings toward the outdoor brand I purchased are positive. | 0.904 | ||

| Overall, my attitude toward the outdoor brand I purchased is favorable. | 0.891 | ||

| Overall, I like the outdoor brand I purchased. | 0.837 | ||

| Brand Loyalty | 0.869 | 0.672 | |

| I believe that I have a high level of loyalty toward the outdoor brand I purchased. | 0.830 | ||

| I would choose the outdoor brand I purchased first in the future. | 0.880 | ||

| If the outdoor brand I purchased is available in a department store, I would not purchase other brands. | 0.762 | ||

| Outdoor Activity Involvement | 0.944 | 0.849 | |

| Outdoor activities are important to me. | 0.909 | ||

| Outdoor activities are highly relevant to my lifestyle. | 0.938 | ||

| I have a strong interest in outdoor activities. | 0.917 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Green Product | - | ||||||

| 2 Green Price | 0.920 | - | |||||

| 3 Green Place | 0.834 | 0.913 | - | ||||

| 4 Green Promotion | 0.837 | 0.915 | 0.880 | - | |||

| 5 Brand Attitude | 0.280 | 0.244 | 0.209 | 0.255 | - | ||

| 6 Brand Loyalty | 0.464 | 0.497 | 0.552 | 0.467 | 0.488 | - | |

| 7 Outdoor Activity Involvement | 0.323 | 0.350 | 0.395 | 0.348 | 0.239 | 0.491 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Kim, D. The Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Outdoor Brand Attitude and Loyalty: A Bifactor Structural Model Approach with a Moderator of Outdoor Involvement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094216

Liu X, Kim D. The Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Outdoor Brand Attitude and Loyalty: A Bifactor Structural Model Approach with a Moderator of Outdoor Involvement. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094216

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoze, and Daehwan Kim. 2025. "The Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Outdoor Brand Attitude and Loyalty: A Bifactor Structural Model Approach with a Moderator of Outdoor Involvement" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094216

APA StyleLiu, X., & Kim, D. (2025). The Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Outdoor Brand Attitude and Loyalty: A Bifactor Structural Model Approach with a Moderator of Outdoor Involvement. Sustainability, 17(9), 4216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094216