1. Introduction

Bees play a significant role in crop pollination [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Bees are estimated to visit more than ninety percent of the world’s top 107 crops. However, wind- and self-pollinated grasses account for about sixty percent of worldwide food production without animal pollination [

1]. Beekeeping is one of the sustainable agricultural activities that significantly contributes to rural development through its potential role in improving rural women’s livelihood.

Climate change, such as high temperature, is a big challenge for beekeeping sectors and food security. High temperatures could negatively affect insect species’ populations through effects on survival, life cycle, fecundity, and dispersal [

5,

6]. Variations in climate are known to influence the honeybee population, honeybee health, the pollination activity of insects, and their efficiency [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], with a major fall in bees and biodiversity [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, global warming could also adversely affect plant–pollinator mutualism, and subsequently, temporal mismatches among the mutualistic partners might arise [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Beekeepers around the world have adopted several sustainable beekeeping management practices to adapt to climate change. Beekeepers improved their beehive boxes, transferred their beehives to suitable locations, and enriched the honeybees’ food [

23]. Moreover, the adoption of different adaptation strategies such as changing the type and increasing the number of hives reduced climate effects [

24]. Indeed, beekeeping management practices reduce climate stress. The selection of breeds and enhanced placement of hives according to climate situation, supplementary feeding during resource-scarce periods, and integrated pest management (IPM) to control insects, pests, and other stressors [

25].

Agricultural extension services play an important role in enhancing the knowledge needed to promote the adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices and foster the socio-economic status of rural women [

26]. Rural women can overcome barriers to adopting sustainable beekeeping practices by attending training and workshops delivered by the extension department [

27]. Saudi Arabia empowered the beekeeping industry through effective extension services and cooperative associations [

28].

The low dissemination of agricultural advisory services among women hinders women’s decision-making and limits their involvement in agricultural entrepreneurial activities. Inclusive services are crucial for women’s empowerment in agriculture [

29]. Agricultural extension services could empower women, promoting gender equality, rural development, and sustainable practices. They enhance farming expertise and cultural overcoming, disrupting traditional gender norms [

30].

Undoubtedly, gender equality and women empowerment are pivotal to gender transformation and a comprehensive approach to advancing gender in agriculture [

31]. According to Costa [

32], the share of working women in agricultural employment increased from 56% to 64%, and men from 53% to 62%, across the countries. The legislatures of the democratic nations of Europe are fighting against discrimination and encouraging gender equality. Various stakeholders including public administrations, companies, and society are participating in this process [

33]. In 2021, women empowerment was a major concern for the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially at the United Nations Food Systems Summit.

Moreover, the new Common Agricultural Policy (2023–2027) endorsed gender equality in rural areas. The different Member States and researchers discussed the issues faced by rural women and keenly focused on possible solutions to gender equality [

33,

34].

Agriculture contributes significantly to the economy of various countries around the world. In line with the Kingdom’s Vision 2030, the management of available natural resources by adopting sustainable good practices, with emphasis on empowerment of rural women, is one of the major objectives of the KSA agricultural policy. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia provides a great opportunity for women in different sectors to achieve economic security through a sustainable development strategy. Through collaboration between the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Ministry of Water, Environment, and Agriculture (MEWA) of Saudi Arabia, the Sustainable Rural Agriculture Development (SRAD) program was designed and implemented. The program aims to develop capacities, enhance rural incomes of small-scale farmers, while conserving available natural resources [

35]. It covers various sectors, including coffee, rose, rainfed cereals, sub-tropical fruits, honeybees, fisheries, and livestock, involving various stakeholders in the countryside across 11 regions [

35]. On 15 October 2024, FAO Saudi Arabia exhibited International Women’s Day and demonstrated the impactful role of rural women in sustainable agricultural development. Moreover, Saudi REEF and the UN development program organized an event under the theme of Empowering for the Sustainable Future. This event provided income-generation opportunities for rural women through agricultural developments and small and medium enterprises [

35,

36]. In January 2025, Saudi REEF released 2.4 billion in financial support to uplift rural communities across the Kingdom [

37].

Despite the harsh climate and arid conditions in Saudi Arabia [

38], beekeeping is practiced on a large scale in many areas of the country. It is a significant source of income. The beekeeping industry is gradually increasing with several opportunities and challenges [

39]. Beekeeping not only improves families’ livelihood but also grants a healthy sugar source, environmental sensitization, women empowerment, and social organization and plays a vital role in producing sub-products for healthcare and cosmetics [

40]. Implementing beekeeping programs required inclusive mechanisms for choosing suitable beneficiaries and appropriate ongoing extension, training, mentoring, and market access to improve the beekeeping industry [

41].

The Kingdom harvests more than 5000 tons of honey annually. The number of beehives surpasses one million denominations throughout the Kingdom [

42]. In addition, beekeeping practices are carried out on a large scale in Saudi Arabia. Currently, the country is dependent on imports. It has been estimated that more than 15,000 metric tons of table honey are imported from Australia, Turkey, Mexico, Argentina, Pakistan, USA, Germany, and Yemen to meet the demand [

43]. Generally, the prices of imported honey are lower than locally produced honey. However, Yemen supplies honey to Saudi Arabia, and local consumers are ready to pay up to USD 190 per kg. The Kingdom imports about 25,000 tons of honey annually. During the last three years, around 1.3 million parcels at SAR 130 million (USD 34.6 million) were delivered to Riyadh and used by beekeepers to produce honey [

44].

Since 2018, the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (MEWA) launched various programs to promote the honey industry. Honey contributes 1.07 percent to the country’s agricultural GDP. Six programs are running to support the beekeeping industry by developing infrastructure and local honeybee breeds. These programs focus on capacity building, regulating bee pastures, and stimulating investment and scientific research in beekeeping sectors [

42].

In developing countries, rural populations are facing several challenges, including poor infrastructure, low agricultural productivity, vulnerability to natural disasters, climate change, increased aridity [

45], poor market access, inconsistent government policies, poor gender integration, lack of proper agricultural extension service, unfavorable programs, and the cessation of initiatives developed by governments in developed countries as a result of the World Bank financial crisis [

46].

Undoubtedly, rural women play a significant role in developing countries, making up 45% of the agricultural workforce [

47]. Rural women in most parts of the world are involved in agricultural crop production and livestock breeding, providing their families with food, water, and fuel and contributing to non-agricultural activities to diversify their families’ livelihoods [

48]. Many organizations and governments seek to empower rural women for the well-being of individuals, families, and rural communities [

49]. In the 1980s, the World Bank introduced women empowerment in the development process to fight against poverty and social injustice [

35].

The Saudi government has launched an initiative to empower rural women by developing their technical skills in managing and growing small and medium enterprises to fulfill local market demand. The initiative focused mainly on capacity building in various areas of sustainable development, including farming and crafts, and providing important equipment to enhance the quality of small and medium enterprise in the rural areas across the Kingdom’s regions [

50]. Attention to women’s issues and their economic, political, and social empowerment has become a top priority of the Saudi leadership [

51]. The Kingdom’s Vision of 2030 shows that the agricultural sector is a main pillar of sustainable development, where smallholders and producers, men and women, could play a vital role in rural agricultural development. The Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture—facilitated through the Sustainable Rural Development Program, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations—provides technical advisory assistance to develop the capabilities of rural population [

52].

The Saudi Reef program in KSA seeks to achieve environmental and agricultural sustainability by developing rural communities and providing job opportunities and livelihoods to small farmers [

50]. The Sustainable Agricultural Rural Development Program “Saudi Reef” exclusively supports the bee sector by releasing SAR 140 million for 10,584 beneficiaries in various rural areas of the Kingdom. Saudi Reef’s financial and technical support aims to promote local beekeeping to achieve self-sufficiency from honey. The Kingdom established royal bee breeding and stations in Hail, Najran, Jazan, Medina, Tabuk, and Taif to protect the bees from diseases and pests [

50].

Beekeepers are provided with modern beekeeping tools and technologies; three mobile laboratories and four mobile clinics are working to examine and diagnose bee diseases and pests. In the kingdom region, 5850 licenses allow the people of 13 administrative regions, including 1560 beekeepers in the Hail. Therefore, the improved understanding of bee contributions to sustainable development is essential for confirming viable bee systems [

53].

Understanding the level of beekeepers’ satisfaction and their attitudes toward extension services is critical in assessing their preparedness to implement innovative beekeeping practices on their farms. It is also vital for designing relevant extension initiatives. Moreover, analyzing the adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices among beekeepers could also help inform the relevant agricultural institutions and policymakers in designing effective programs for beekeepers to facilitate the adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices at a large scale. Saudi Arabia plans to improve honey production to reduce high import and economic burden. Therefore, the current study assesses beekeepers’ satisfaction and attitudes towards sustainable beekeeping practices in Saudi Arabia.

3. Results

Table 1 indicates the respondents’ socioeconomic and beekeeping characteristics. Most respondents (53.3%) were in the age group of 37 to 53. Only 40.2% of the respondents were less than 37 years old. Less than 5% of the respondents were more than 53 years old. Less than 5% of the respondents did not respond regarding their age. More than three-fifths of the respondents had obtained a university education. Only 32.6% of the respondents had basic education, and 4.3% were illiterate.

Over two-thirds of the respondents are involved in the beekeeping and processing industries. Specifically, 31.5% and 15.2% of the respondents practice beekeeping and processing, respectively. Less than 3% of the respondents did not respond regarding their occupation. Over three-fourths of the respondents were involved in full-time beekeeping and honey production. The remaining respondents were employed in the government sector (7.6%), private (2.2%) sector, or retired (5.4%). More than two-fourths of the respondents earned their primary source of income from beekeeping and being involved in trade and additional income. Only 31.5% of the respondents were involved in beekeeping as a hobby. Only 1.1% of respondents did not respond to the purpose of beekeeping. More than four-fifths of the respondents were earning less than SAR 5000. Additionally, 14.2% of the respondents earned from SAR 5000 to less than SAR 15,000. However, 5.4% of the respondents did not respond regarding their monthly income. More than half of the respondents had two years or less than two years of experience in beekeeping. Only 31.5% and 10.9% of respondents had up to six years and more than ten years of experience in beekeeping. Only 1.1% of the respondents did not respond regarding their experiences in beekeeping. More than 35% of respondents owned pastureland for beekeeping. In comparison, 25%, 26.1%, and 5.45% of respondents owned valleys, private farms, and protected land, respectively. More than three-fifths of respondents had a beekeeping practice certificate. Only 28.3% of respondents did not possess a beekeeping practice certificate.

More than three-fourths of respondents used modern hives. Only 15.2% of respondents used traditional hives. More than three-fourths of respondents had a hundred or less than a hundred hives. Only 16.3% of the respondents had more than a hundred hives. More than four-fifths of respondents produced 1000 kg or less of honey annually. Only 8.7% of respondents produced more than 1000 kg of honey annually.

Table 2 shows the respondents’ source of information regarding beekeeping. All responses were arranged in descending order by the average score. The results indicated that the mean score ranged from a maximum of 3.99 to a minimum of 2.94. For the source of information regarding beekeeping, “specialized agricultural websites” ranked first with an average score of 3.99. On the other hand, the “universities” ranked last with an average score of 2.94.

Table 3 shows the need for professional guidance regarding beekeeping. All responses were arranged in descending order by the average score. The results indicated that the mean score ranged from a maximum of 4.15 to a minimum of 3.82. For professional guidance regarding beekeeping, “productivity efficiency and honey quality” ranked first with an average score of 4.15. On the other hand, “processing industries” ranked last with an average score of 3.82.

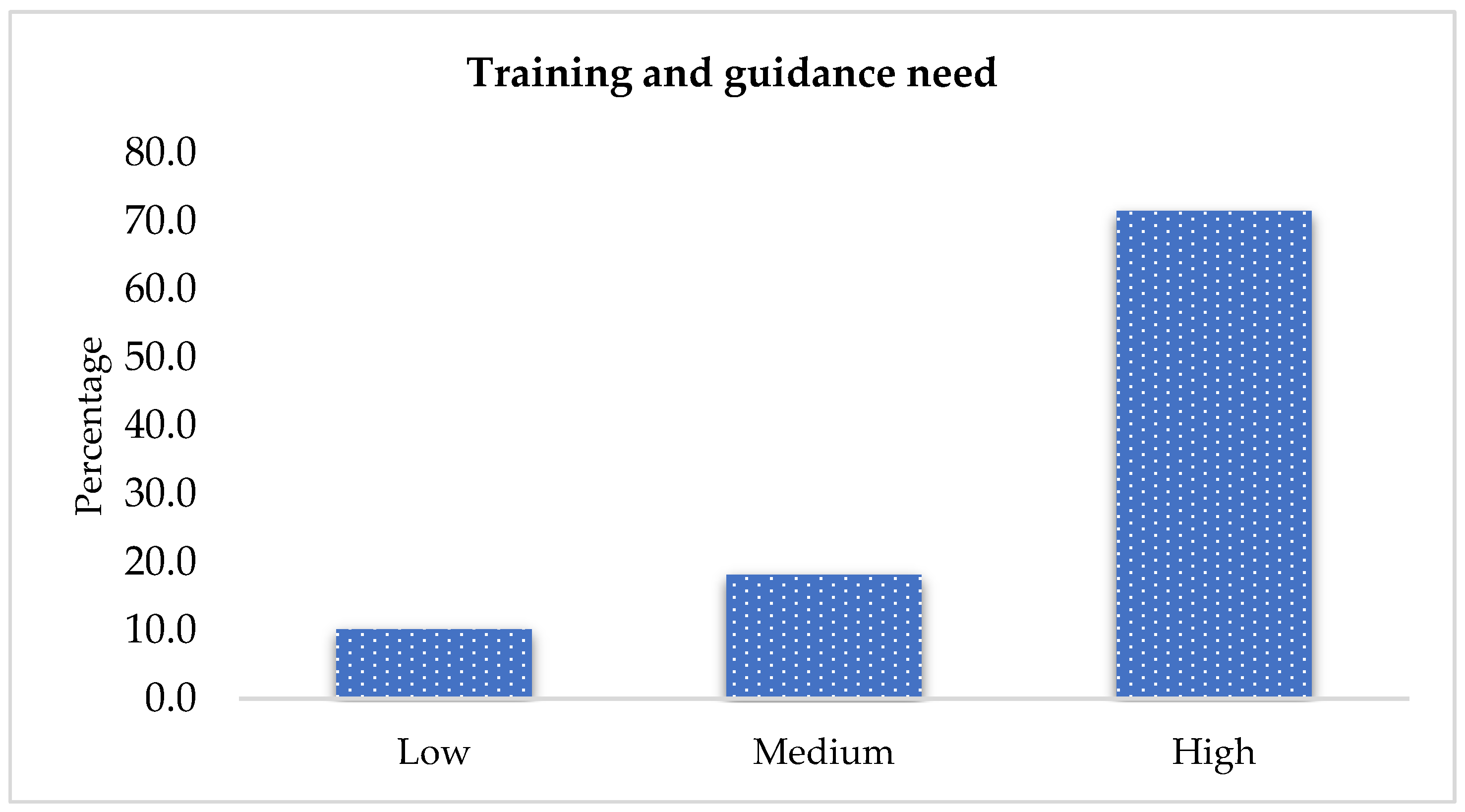

Figure 1 shows beekeepers’ needs for professional guidance and training regarding beekeeping. The majority of the respondents (71.74%) showed a high need for professional guidance and training regarding beekeeping, whereas 18.48% and 9.78% of respondents expressed a medium and low need for guidance and training, respectively.

Table 4 shows the beekeepers’ satisfaction regarding extension services. All responses were arranged in descending order by the average score. The results indicated that the mean score ranged from a maximum of 3.63 to a minimum of 3.30. For beekeepers’ satisfaction regarding extension services, “awareness campaigns and agricultural extension caravans” ranked first with an average score of 3.63. On the other hand, beekeepers’ satisfaction regarding the extension service “support for processed agricultural products manufacturing” ranked last with an average score of 3.30.

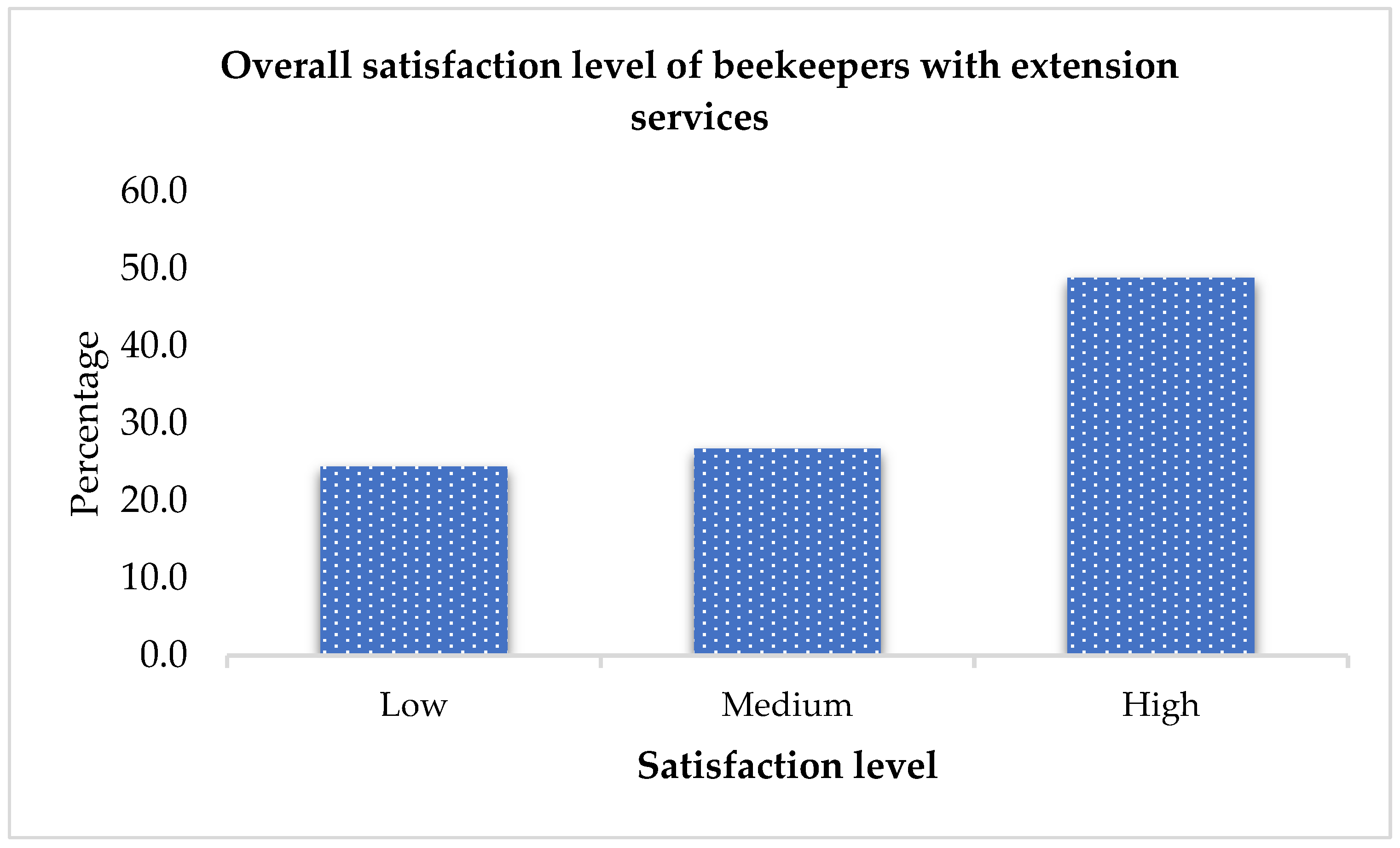

Figure 2 shows beekeepers’ overall satisfaction regarding extension services. The majority of respondents (45.7%) showed a high satisfaction level regarding extension services, whereas 25% and 22.5% of respondents showed medium and low satisfaction, respectively.

Table 5 shows the beekeepers’ attitudes towards extension services. All responses were arranged in descending order by the average score. The results indicated that the mean score ranged from a maximum of 4.08 to a minimum of 3.66. For beekeepers’ attitudes towards extension services, “The Reef Program is beneficial and well-directed in supporting beekeepers” ranked first with an average score of 4.08. On the other hand, beekeepers’ attitudes towards the “Effectiveness in the institutions that adopt ideas and development, including the Rural Development Program” ranked last with an average score of 3.66.

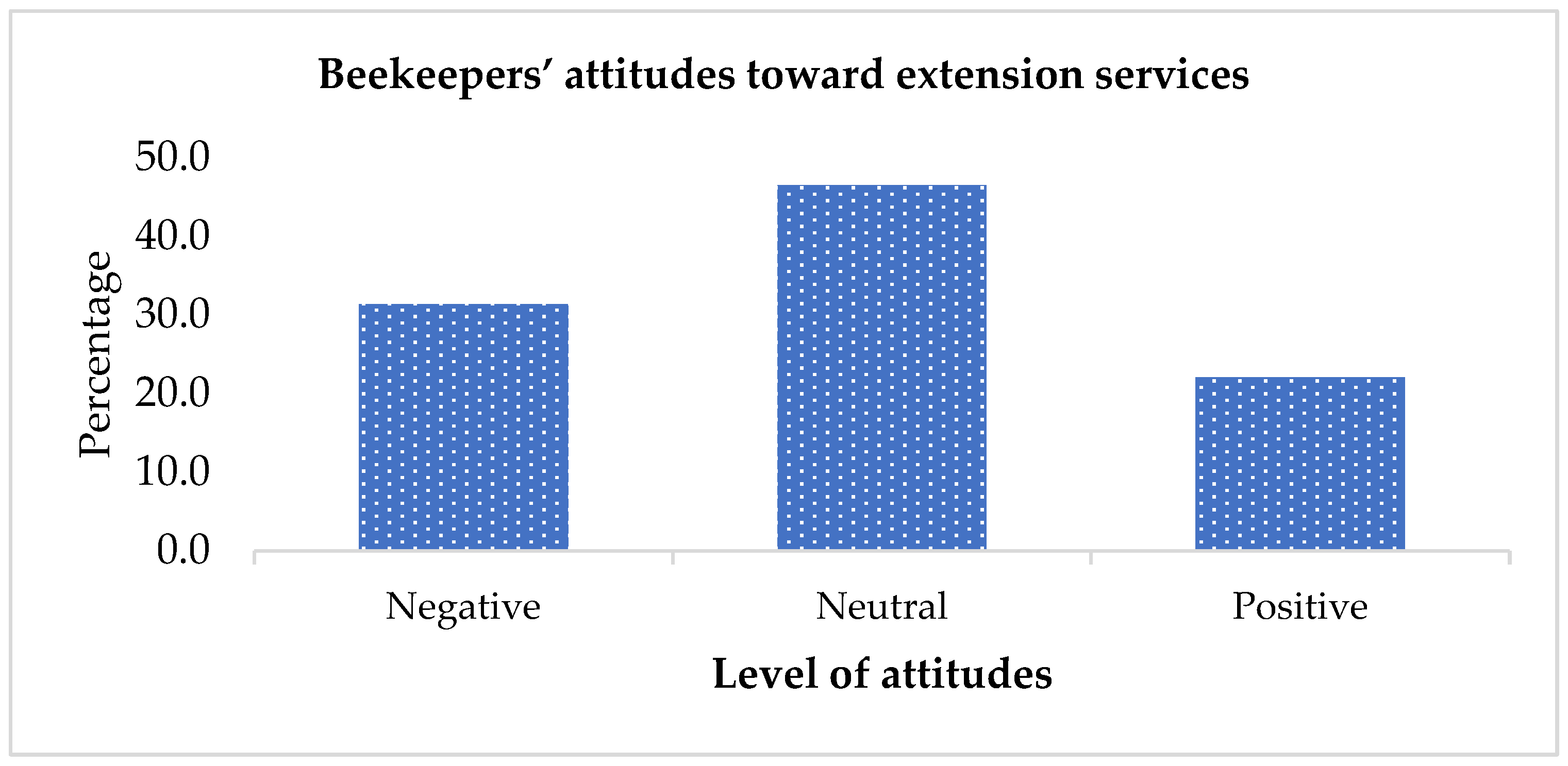

Figure 3 shows the beekeepers’ overall attitudes toward extension services regarding beekeeping. The majority of the respondents (43.5%) were neutral, whereas 22.1% and 31.4% of the respondents showed positive and negative attitudes towards extension services.

Table 6 shows the industrial processing of beekeeping products. All responses were arranged in descending order by the average score. The results indicated that the mean score ranged from a maximum of 3.15 to a minimum of 2.43. The industrial processing of honey for “body care products” ranked first with an average score of 3.15. On the other hand, the industrial processing of honey for “royal jelly” ranked last by an average score of 2.43.

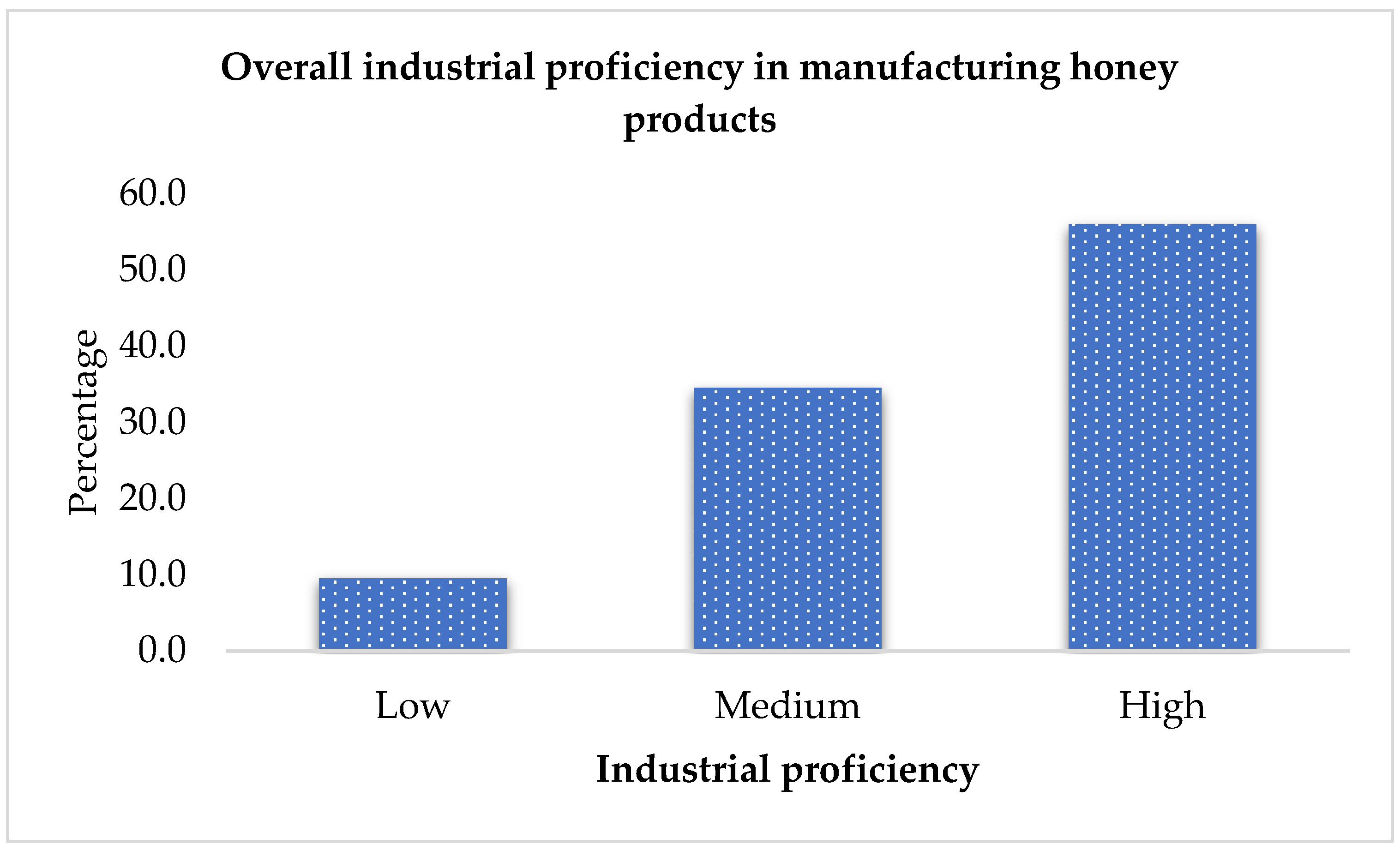

Figure 4 shows the overall industrial proficiency in manufacturing honey products. The majority of the respondents (51.1%) expressed high proficiency in honey products, whereas 31.5% and 8.7% of the respondents showed medium and high industrial proficiency in making honey products, respectively.

Table 7 shows the adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices among beekeepers. All responses were arranged in descending order by the average score. The results indicated that the mean score ranged from a maximum of 4.36 to a minimum of 3.75. For the adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices, “scientific methods are followed to protect bees from poisoning and pesticides” ranked first with an average score of 4.36. On the other hand, “Joinery of wooden beehives,” ranked last with an average score of 3.75.

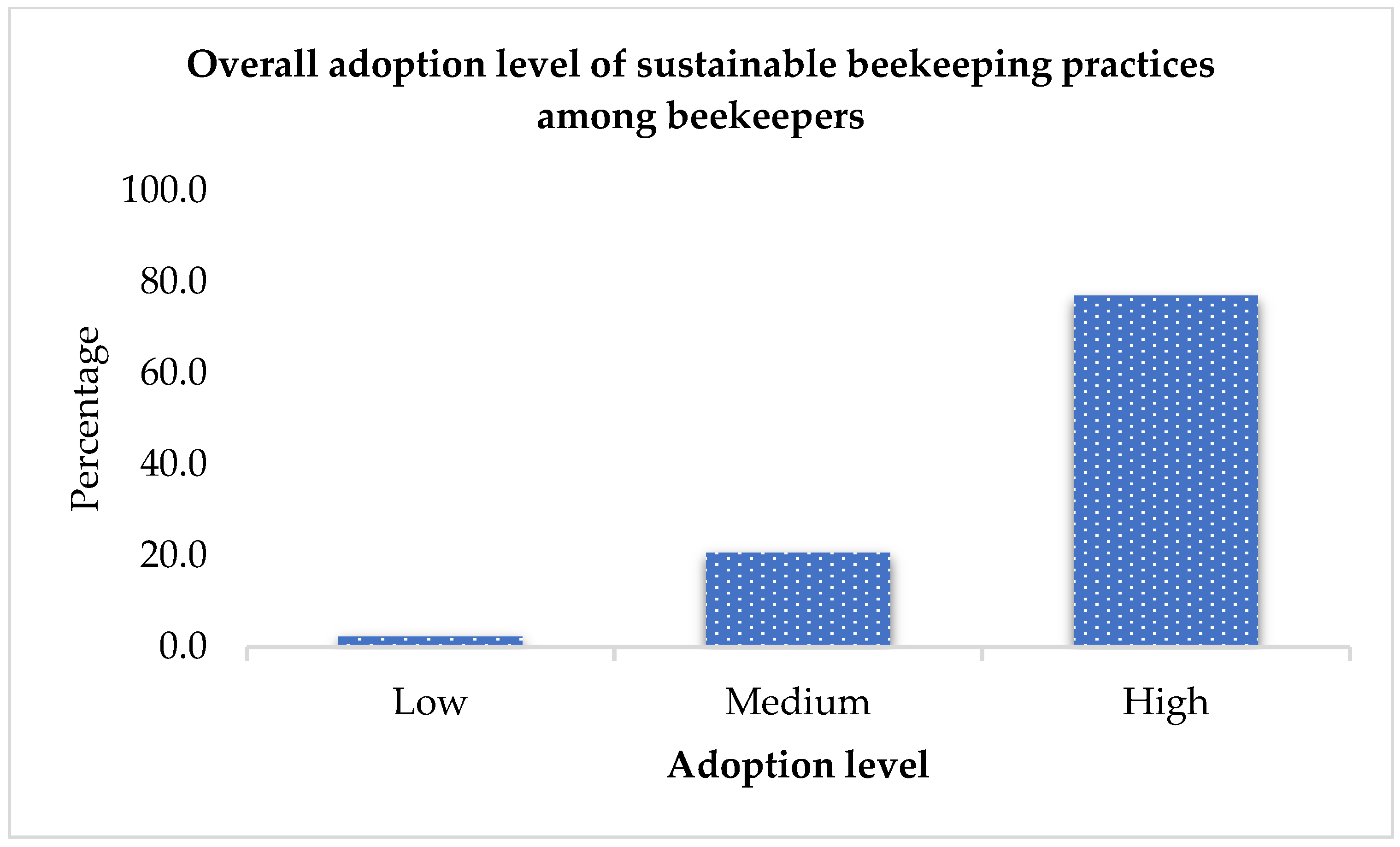

Figure 5 shows the overall adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices among beekeepers. The majority of the respondents (72.8%) adopted sustainable beekeeping practices at a higher level, whereas 19.6% and 2.2% of the respondents adopted sustainable beekeeping practices at a medium and low level.

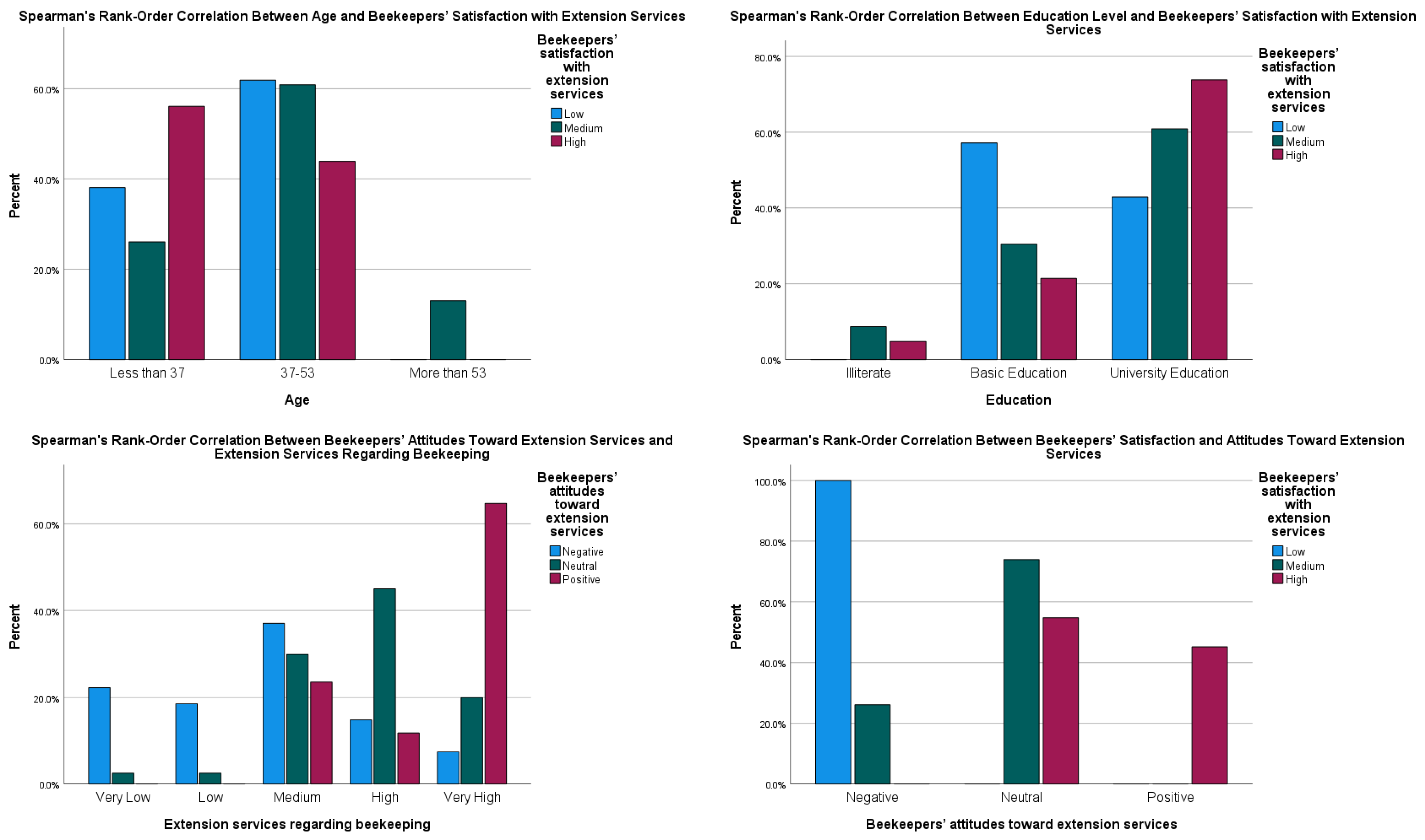

Figure 6 presents Spearman’s correlation between age, education, extension services regarding beekeeping, beekeepers’ satisfaction with extension services, beekeepers’ attitudes toward extension services, and beekeepers’ satisfaction with extension services.

Table 8 presents Spearman’s rank-order correlation analysis to determine the relationship between the respondents’ demographic characteristics and their satisfaction with extension services, beekeepers’ attitudes toward extension services, and adoption of beekeeping practices among beekeepers. Age had a significant negative correlation with beekeepers’ satisfaction with extension services (r = −0.330 **,

p = 0.01). Young beekeepers are less likely to be satisfied with extension services than older beekeepers. Education level showed a significant positive correlation with beekeepers’ satisfaction with extension services (r = 0.247 *,

p = 0.05). Beekeepers with higher educational qualifications are more likely to be satisfied with extension services than those with a lower educational level.

Beekeepers who received extension services showed a negative and significant correlation with their attitudes toward extension services (r = −0.0241 *, p = 0.01). It means the lack of extension services among beekeepers builds negative attitudes toward beekeeping. Beekeepers’ satisfaction with extension services shows a significant positive correlation (r = 0.497 **, p = 0.01) with beekeepers’ attitudes toward extension services. It means higher satisfaction with extension services among beekeepers improved their attitudes.

4. Discussion

This research investigates beekeepers’ satisfaction and attitudes toward extension services. In addition, it provides deep insight into sustainable beekeeping practices among beekeepers in Saudi Arabia. Findings revealed that most beekeepers were satisfied and presented neutral attitudes toward extension services. Those who participated in extension programs and training sessions gained entrepreneurial benefits. Strong [

59] found extension agents disseminated innovative and sustainable beekeeping technologies to improve honey production in Kenya. Beekeepers who frequently visited the extension office were more aware of sustainable beekeeping technology. They had self-confidence about entrepreneurial behavior, and seemed more satisfied regarding extension services provided and economic gain. In the USA, Land Grant University provides online platforms like bee clubs, extension services, and apiary management technologies [

60]. Beekeepers in the study area might gain similar support, improving their satisfaction with extension services. Beekeepers might be highly dependent on extension agents for technical advice. Extension services would increase their satisfaction and build confidence in communication. Similar findings regarding the role of agricultural extension agents have been reported by various researchers [

61,

62,

63]. Our results contradict the findings of a qualitative study conducted by Benge and Amy [

64], who revealed that commercial beekeepers were dissatisfied with extension services and being neglected when compared to hobby-type beekeeping practices. Commercial beekeepers have lost trust in extensions due to the beekeeping information that is published through the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS), which is more for hobby beekeepers. Furthermore, they found that many extension agents showed less interest in commercial beekeeper education.

The neutral attitudes of beekeepers toward extension services might be due to various factors such as poor extension services, lack of interest in extension services, and weak government policies. Our findings contradict with the findings of a qualitative study conducted by Gikunda et al. [

65], which revealed negative attitudes toward honey beekeeping among women. The reasons behind the negative attitudes among women were cultural restrictions such as taboos, inheritance, and traditions. Moreover, youth learned honey beekeeping skills from their parents only. They demanded strong agricultural extension services regarding honey beekeeping technologies. Anaeto et al. [

66] reported that extension agents are commonly responsible for improving knowledge and skills and changing attitudes [

61]. The lack of access to external information negatively affects farm productivity and may keep beekeepers’ attitudes neutral [

67,

68]. Beekeepers in the study area might face similar challenges. In Saudi Arabia, there is a dire need to improve women’s participation in beekeeping enterprises, extension training, and programs. Mburu et al. [

69] found high participation of rural women in apiary management due to commercial insect programs, training, and the adoption of modern beekeeping practices.

Findings indicate high adoption of sustainable beekeeping practices among beekeepers. They might hold innovative information on the advantages of adopting sustainable beekeeping practices. It can be expected that beekeepers might have attended training sessions about advanced beekeeping techniques as the Bee Research Unit at King Khalid University and Aramco company initiated a training program entitled “Beekeeping and Bee Products” and the Beekeepers Cooperative Society in Rijal Alma has a program which purposes to train 160 people [

70].

The findings reveal that young beekeepers seem less likely to be satisfied with extension services. Low satisfaction with extension services among young beekeepers might result from poor extension services or low interest and reliance on traditional information instead of extension contact. Our findings contradict with that of Feketéné Ferenczi et al. [

71], who conducted a qualitative study and found higher satisfaction regarding professional instructions about honey beekeeping. Young beekeepers reported that beekeeper workshops helped them in learning honey beekeeping practices. Beekeepers’ information varies according to conditions. Organized training, skills development programs, and management techniques should be provided to young beekeepers to improve their satisfaction. The extension department must investigate the reasons for low satisfaction with extension services provided to young beekeepers [

72].

Highly qualified beekeepers seemed satisfied with the extension services. Education among beekeepers is essential for successful beekeeping [

73]. Education builds capacity, belief, and improved attitudes. Educated beekeepers have a great ability to understand the objectives of extension services and the advantages of innovative beekeeping technology disseminated by extension agents for desired purposes [

60,

74]. A qualitative study conducted by Mulatu et al. [

75] revealed that the educated beekeepers have more access to innovative information, and the possibility of attending professional training. They also influence farmers′ adoption of contemporary hive beekeeping technologies and participate in income-generating diversification initiatives.

Beekeepers are facing various challenges due to irrelevant knowledge. A study conducted in the UK suggested that the government should make an effort to overcome these challenges. Meanwhile, the government of Saudi Arabia is striving to improve the technical knowledge of beekeepers through effective extension services [

76].

Findings revealed that low dissemination of extension services caused negative attitudes toward extension services. A report prepared for the Sustainable Rural Agricultural Program (SARD) mentioned the advantages of the beekeeping sector in achieving the country’s economic goals, as expressed in Vision 2030. Progress towards developing the beekeeper sector can be achieved through institutional support, and training extension staff at various levels [

44]. Therefore, it is understood that poor extension service might reduce honey production and demotivate beekeepers towards extension services. The improvement in extension services among beekeepers was suggested in a report published by MEWA [

44].

For instance, In sub-Saharan Africa, beekeepers improved beekeeping practices, adopted sustainable beekeeping practices through extension services, and initiated enterprises [

73]. Moreover, it reported that beekeeping extension services were largely provided by NGOs and public agricultural extension departments. Public agricultural extension services and private consultants mostly delivered agricultural extension services for other agricultural enterprises to non-beekeepers. Extension service officers and/or NGOs critically promote the adoption and persistence of sustainable beekeeping. For instance, several extension services have been subcontracted by the Ugandan Government to private service agents to balance the operating costs of frontline agricultural extension delivery in remote areas [

77]. This demand was made by extension service providers, who tend to favor training, skills development, and equipment provision to farmer groups rather than individual farmers [

78,

79].

The findings revealed that satisfaction with extension services among beekeepers improved their attitudes toward extension services. Understandably, the quality, availability, accessibility, diversity, relevance, and effectiveness of extension services ultimately built positive attitudes [

80,

81]. According to researchers’ observations, rural women started beekeeping for economic benefits. They stated that disseminating innovative beekeeping techniques could improve their knowledge and income. Rural women were completely dependent on extension services in terms of beekeeping. Only a satisfactory degree of extension services might improve their attitudes toward extension services. Verbeke et al. [

82] reported that beekeepers’ attitudes are driven through extension services and facilities to target markets by involving various stakeholders.

5. Conclusions

This study assesses beekeepers’ satisfaction and attitudes towards extension services and the level of adoption of recommended beekeeping practices among rural women in the Hail region, Saudi Arabia. Beekeepers were highly satisfied and showed neutral attitudes toward extension services. Despite the neutral attitudes toward extension services, a considerable portion indicated a higher adoption of recommended beekeeping practices. Moreover, rural women needed professional guidance and training for beekeeping.

Beekeepers in the young age group seemed less satisfied with the extension services. Highly educated beekeepers were more satisfied with the extension services. The decreased delivery of extension services to beekeepers decreased their attitudes toward extension services.

The findings of the study may have various policy implications. First, policymakers should understand the foremost obstacles to extension services. Initiatives should be put in place to educate the rural women who are involved in beekeeping sectors. Combined efforts should be made by governments, policymakers, and the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture to initiate training sessions for extension agents to improve the satisfaction and attitudes of beekeepers. Satisfaction and positive attitudes toward extension services could make knowledge transfer easy among beekeepers. Moreover, new research should be conducted to investigate the innovative, practical viability, and potential of sustainable beekeeping practices as an alternative to traditional beekeeping practices. The results of future research should be used for policymaking to stimulate sustainable beekeeping practices at the local level and, in turn, to reach one of the core goals of Vision 2030 for sustainable honey production.

The present study selected rural women involved in beekeeping only from the Hail governorate. The study findings may not be generalizable to beekeepers of other regions. It is, therefore, implied that similar research should be conducted in other regions of Saudi Arabia.

_Li.png)