Abstract

Developmental approaches over time have been largely economistic and overlooked local sustainability preconditions. They were greatly influenced by a host of doctrines, theories, and strategies argued through macro-level, macro-scale policies. This research retrospectively views these approaches as they have evolved post-WWII and their effect on sustainability at a community level. It eventually focuses on a specific community-level developmental strategy, i.e., “microfinance”, which has led to the establishment of millions of microenterprises. In recent decades, community-based enterprise (CBE) development has been a widely practiced mode of developmental intervention to develop underdeveloped communities in developing countries. The primary goal of CBEs is to generate profit for people’s livelihood. This research indicates that CBEs offer potential. They can be ecologically sustainable and socially responsible too. A shift in the present model to encourage CBEs’ pursuit of ecological principles is tenable. Foucault’s notion of “dispositif” allows such a shift with incorporation of environmental alongside economic and social goals as a new strategic disposition (model). Therefore, this study presents a social–ecological model of CBE and asserts that it embeds the necessary components to bring about sustainability at a community level.

1. Introduction

The notion that “a rising tide floats all boats” is fading away [1,2]. The idea that mere economic progress is the key to development [3,4] is no longer tenable. The top-down developmental approaches argued by trickle-down economic theories had a central argument that “economic development” ensures national prosperity [5]. Development programs by global agencies, therefore, adopted trickle-down mechanisms to develop the “underdeveloped” regions across the world—especially in Asia, Africa, and Latin America—after WWII. Escobar [6] states that since the 1950s (post-WW-II), the developmental process has been more of an un-underdeveloping task in developing countries by subjecting their societies to increasingly systematic, detailed, and comprehensive interventions.

In recent decades, a myriad of schools of thought started to view development based on the relative necessity and importance of the process for particular social and ecological contexts [7,8]. One such “un-underdeveloping” task manifested prominently as “microentrepreneurship” by economically disadvantaged people in rural communities with the help of NGOs. From 2000, this style of NGO-led developmental approach emerged as a popular grassroots intervention mechanism; eventually, it helped create millions of community-based enterprises (CBEs), especially in the developing world [9]. Typically, global developmental bodies, such as the UN agencies, the World Bank, and other regional developmental banks, primarily follow a macro-scale top-down approach towards development. Such approaches are usually maintained at national and international scales and reflect the structural and macroeconomic agenda.

The view of “indoctrinated developmentalism” refers to a mode of developmental thinking and practice that is disproportionately shaped by Western-centric paradigms of economic growth, sustainability, and resource management. Within the context of community-based enterprises (CBEs) in the Global South, it denotes a normative framework wherein access to, and control over, community-based production and economic empowerment mechanisms are subsumed under externally imposed logics of development. This often results in the marginalization of indigenous knowledge systems, local autonomy, and context-specific pathways to community resilience and self-determination. With such indoctrination of developmental paradigms, it is largely unknown whether sustainability and well-being issues at the community level are adequately addressed. The question arises: can CBEs support community-level sustainability (as they operate in the community and are run by community members)?

The question of community-level sustainability has gained much traction in recent decades. Global development agendas, such as Rio Declaration 1992 and UN-MDG 2000, have emphasized sustainability; the contemporary Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), meant to be pursued until 2030, aim to bring about sustainability at all levels—local to global. Scoon [10] suggests that there are clear opportunities for the insertion of sustainability agendas in new ways into policy discourse and practice at all levels (from local to global) since addressing climate is central to those policies and planning. Nevertheless, the literature on the potential of CBEs to contribute to community-level sustainability is scant.

The CBE modality considers economic benefit as a prime goal [11]. The benefits transcend to the societal level too, as CBEs help empower women, contribute to social equality, and foster social capital [12,13]. However, the modality pays little or no attention to the ecological benefit [14]. Evidence suggests that CBEs have the potential to support sustainability from the bottom as grassroots organizations [7,15]. As developmentalism is a dynamic process, it can be presumed that redesigning the CBE modality with the inclusion of ecological objectives (alongside its economic and social contributions) might bring about sustainability at the local level. Therefore, this paper aims to argue whether a shifted microentrepreneurship modality with the inclusion of ecological objectives would result in a new framework for local sustainability.

2. Developmentalism: Shifting Focuses

Developmentalism is marked by shifting focuses over time [16,17]. The history of development practice shows how the debates among eighteenth- and nineteenth-century philosophers became a practical pursuit during the twentieth century [18]. The Marshall Plan, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Stalin-styled export of Soviet industrialism and communism all represented significant policies that were put into effect through interventions with “nations perceived as being underdeveloped” [19]. These policies and their funding spawned a plethora of development programs ranging from small-scale community development work to large-scale economic and political interventions [18]. While the issues of economic, social, and political well-being were in focus, ecological issues were mainly missing in these policies or intervention strategies until recently [7].

Modern development debates, as opposed to the more general debate about the causes of poverty and economic growth, date back to the early post-WWII period. They are closely associated with the approaches of decolonization, nation-building, national planning, and development aid over the new international economic order [20,21,22]. These developmental approaches entail many evolving theories, hypotheses, models, techniques, and empirical applications. In taking stock of these developmental approaches, Thorebcke [7] and Shahidullah [16] indicated their focuses in specific decades; following their summary, the table here (Table 1) provides decade-wise excerpts (Table 1):

Table 1.

Developmental approaches and focus since 1950s.

During the 1950s, economic growth became the primary policy objective in the newly independent (decolonized) less developed countries, adopting an “industrialization-first strategy.” The strategy was advocated by a belief that economic growth and modernization would eliminate income and social inequalities. Theories that contributed to subsuming such belief by the development economists were the “big push” [23], “balanced growth” [24], “take-off into sustained growth” [25], and “critical minimum effort thesis” [26].

Building on such theoretical and conceptual developments of the 1950s, the dual economy model came into being and became more sophisticated in the 1960s. It recognized the interdependence between the functions of the modern industrial and outmoded agricultural sectors [27]. However, one of the major underlying flaws of this approach was that “growth” and “development” were thought to be synonymous [28]. The dual economy model, therefore, fueled intense debate, as anti-poverty programs and wealth redistribution did not go hand in hand.

The decade of the 1970s witnessed a shift in the preference (welfare) function—away from aggregate growth per se and toward poverty reduction and increasing investment transfers in projects benefiting the poor [29]. The rising number of people in a state of poverty led to the incorporation of “poverty alleviation” as one of the key development objectives other than GNP growth. Theoretical approaches such as the package approach in traditional rural areas, the role of the informal sector, rural–urban migration, underdevelopment theory, and dependency theory underpin these policies and strategies. The key intervention mechanisms were integrated rural development, comprehensive employment strategies, redistribution with growth, basic needs, reformism (asset redistribution), and radical collectivist strategies.

Development strategies in the 1980s dealt with many macroeconomic adjustments, termed structural adjustment policies. The neoliberal theory of economic development came to dominance, whereby privatization and free trade were intensely promoted in the economic sphere. In the 1990s, however, good governance, the role of institutions in development path dependency, and the endogeneity of policies and social capital were the theoretical lenses that helped resurface poverty alleviation and improved socioeconomic welfare as core agendas for underdeveloped countries.

After 2000, the key objectives of development doctrines comprised human development and poverty reduction—addressing inequality and vulnerability. Global developmental agendas, e.g., the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), subsumed many goals. Two dominant policies, globalization as a development strategy and the search for pro-poor growth, have been adopted by most countries [30,31]. The political economy of development and the role of institutions reclaimed significant dominance in the theoretical sphere of development, where one of its major tenets is that “more equal initial income and wealth distribution is consistent with and conducive to growth” [16].

3. Community-Level Sustainability

Sustainability implies a system’s ability to survive or persist; biologically, this means avoiding extinction and living to survive and reproduce; economically, it means avoiding major disruptions and collapses, hedging against instabilities and discontinuities [32,33,34,35]. Berkes et al. state that sustainability is maintaining the capacity of ecological systems to support social and economic systems [36]. Therefore, it is considered a process, rather than an end product, a dynamic process that requires adaptive capacity for societies to deal with change [35,36]. Several important events and political actions and the subsequent outcome documents helped evolve the eventual notion of sustainability; these are the (i) Stockholm Conference on the Human and Environment and the establishment of UNEP in 1972 [37], (ii) “Limits to Growth Report” [38], (iii) “US Global 2000 report to the president” [39], (iv) The Resourceful Earth [40], (v) “The World Conservation Strategy” [41], and, most notably, (vi) UN Brundtland Commission Report, “Our Common Future” [42].

The aforementioned strategy and policy documents looked at the idea of sustainability as a macro-level approach where state, regional, or international bodies are the key actors in putting the sustainability process into practice. Thus, the classic notion of sustainability holds that societal, environmental, and economic objectives are mutually reinforcing, and the process is argued mainly at national and international scales. For example, the practice was more visible in the realms of multi-lateral negotiations (climate, trade, biodiversity, and other similar discourses) and policies of global organizations (the UN, World Bank, and other development agencies). Escobar [43] observed that although sustainability appeared as a broader process in the problematization of global survival, the slogan “think globally, act locally” assumes not only that problems can be defined at a global level but also that they are equally compelling for all communities. Similarly, other scholars started to question popular discourses on globalization and sustainable development, stating that “since global discourses are often based on shared myths or blueprints of the world, the political prescriptions flowing from them are often inappropriate for local realities” [44] (p.683).

Indeed, the political and cultural difficulties in achieving sustainability at a global level justify the considerations of sustainability at the community level [45]. By shifting the focus on sustainability to the local level, changes are seen and felt more immediately. Terms such as “sustainable society” or “a sustainable world” are meaningless to most people since they encapsulate abstraction levels irrelevant to their daily lives. Contrarily, “locality” bears a significant meaning and sense to people as it is the very level of social organization where the consequences of environmental degradation or results of interventions are most keenly felt by and noticeable to stakeholders [7]. And, of equal importance, there tends to be greater confidence in government action at the local level. Yanarella and Levine [46] envisioned that sustainable community development would ultimately be the most effective means of demonstrating the possibility that it can be achieved also on a broader scale.

Youngberg and Harwood [47] suggest that sustainability at the community level may demand a specific approach, as the complex nature of interrelationships between nature and societies in diverse geographic locations and topographic realities would not allow for applying a “one size fits all” solution. Meanwhile, the idea of community-based sustainable development as a bottom-up approach came to the forefront [48]; scholars, e.g., Luloff and Swanson [49], Bridger [50], and Wilkinson [51], underscore that sustainable development rooted in place-based communities has the advantage of flexibility, as the communities differ in terms of environmental problems, natural and human resource endowments, levels of economic and social development, and physical (i.e., geological and topographical) and climatic conditions.

Bridger and Luloff [45] see community-level sustainability as an approach that meets the economic needs of local people, enhances and protects the local environment, and promotes more humane local societies. Findings from the UN Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) of 2005 evidence the fact that people are integral parts of ecosystems, and a dynamic interaction exists between humans and the environment [52]. The assessment finds that 15 of the 24 ecosystem services (ESs) that directly contribute to human well-being are being systematically degraded, and development initiatives and their progress would not be sustained if they were to continue to degrade [52,53]. Future scenarios on local human–environment symbiotic relations indicate a severe and irreversible decline in these ESs [52,54]. Therefore, it is crucial to see sustainability as a community-level approach designed with policies and practices sensitive to the opportunities and constraints inherent to local people and the environment [55].

4. Community-Based Enterprises: New Developmental “Dispositif”

The post-2000 developmental agenda [e.g., MDG, MA, SDG] brought three elements to the forefront of developmental discourse: (i) management of ES for human well-being; (ii) action at the local level, with local organizations as the key actors; and (iii) enterprise development at the community level as a widely practiced developmental intervention tool [52,56,57]. Unlike traditional developmentalism, enterprise development emerged as a popular intervention tool and helped create millions of microenterprises, especially in the developing world [58]. The rural community-based microenterprise development initiative has a mainly economic and, to some extent, social development agenda [11,59]. These microenterprises, as an offshoot of the microcredit movement, are perceived to be workable in easing some of the woes of economic and social inequalities at the bottom by creating entrepreneurial subjects, generating alternative income sources, forming social capital, and empowering women [7,14]. As bringing about sustainability at the community level is a more significant task, is it tenable to put these three elements together in the developmentalism discourse, especially in community-level developmentalism?

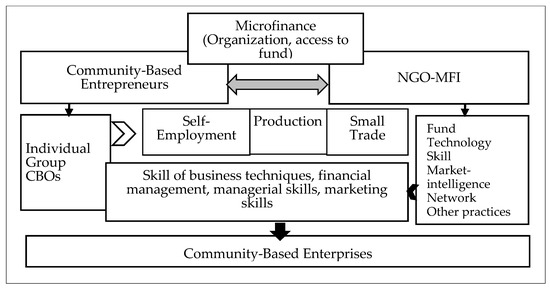

The efficacy of the “community-based enterprise” (CBE) as an instrument for developmentalism, especially poverty reduction, is supported by a vast body of literature, e.g., Pitt and Khandaker [12]; Mayoux [60]; Afrin et al. [61]. Many authors, including Dowla [62] and Rankin [63], note that CBEs contribute to social capital formation at the community level. More importantly, the CBE modality is seen as a “bottom-up” [64] and gendered [60] approach to development. However, there are scholars, e.g., Chen and Dunn [65], Tripathi [66], and Foose [67], who contest the positive impact of microenterprise-oriented developmentalism and point out numerous aggravating challenges that the initiative faces. Despite such debates, the CBE modality became even more popular with the advent of NGOs being a key development partner at the community level, and it started to play a greater role than prior to 2000 [15]. As NGOs emerged as a crucial developmental actor with the downsizing of state-based social welfare and development functions, the proliferation of CBEs occurred across the communities of developing countries, e.g., Bangladesh. Shahidullah [14] states that the shift, i.e., NGOs being a key community-level developmental actor, signaled a dispersion of developmentalism itself. The following figure (Figure 1) exhibits the actors and elements of the classic CBE model that emerged out of microcredit-based developmentalism with NGOs as a key facilitator.

Figure 1.

Actors and elements of the classic CBE model.

In this model, NGOs seem to have shouldered the task of “un-underdeveloping” at the community level. Consequently, NGOs’ wide adoption of microfinance mechanisms became a dominant developmental phenomenon. Many NGOs literally turned to be microfinance institutions (MFIs), while many others incorporated microfinancing as a key component of their operation. Apart from offering access to funds to people in the community, the qualitative changes that the shift brought are the dispersion of skills and knowledge on new and diversified ventures [14,15,16]. The capacity of a community’s entrepreneurs is further enhanced with training on production technologies, market intelligence, networks, and linkages—most of which come as a bundle with microfinance [16]. Nonetheless, the sustainability and implications of this dispersion of developmentalism are largely unknown. There is hardly any study that can concretely establish the comprehensive efficacy of microfinance or, on the contrary, deny its developmental benefit outright. Sen [68] mentioned that many of the developmental achievements of post-1970 Bangladesh are the outcomes of NGO operation along with public policy—recognizing in particular the contributions of two major microfinancing organizations, BRAC and Grameen Bank, that are championing the establishment of CBEs across the globe.

5. A Social–Ecological Model of Community-Based Entrepreneurship

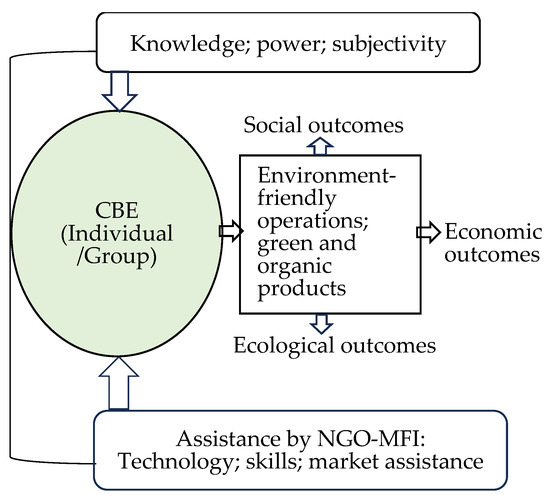

The CBE modality contributes at the local level with proven economic (e.g., poverty reduction) and social (e.g., women’s empowerment, building social capital) outcomes—but it misses a key element, i.e., environment, to be supportive of “sustainability” [15]. The present operative mode of most microenterprises has negative environmental impacts [69] due to several reasons: their sheer number, ubiquitous presence, extended hours of operation, lack of supervision by regulatory and environmental agencies, low technological level, and a lack of supporting infrastructure and services [70]. However, evidence suggests that CBEs can go green with the help of NGOs [15]. Microenterprises that maintain sustainable production techniques, such as organic inputs, reforestation, recycling, controlled water usage, natural pesticides, solar water pumps, and other conservation measures, can support sustainability [71]. Thus, an environmental orientation of the CBE modality can have dual benefits in offsetting the negative impacts and enhancing the positive contributions to ecosystem services (ESs) [15].

Against such backgrounds, a shifted CBE modality with the inclusion of ecological objectives (along with the economic and social) promises to ensure sustainability at the community level. The shift is tenable, as developmentalism is a dynamic process [16]. There might be concern about what conceptual or theoretical structure would allow for accommodating such a shift. Brigg [72] draws on Foucault’s notion of “dispositif” to capture the microcredit-led developmental approach in part and then to question the traditional developmentalism in place [73]. “Dispositif” is a French-loaned term that means apparatus or device or deployment—scholars used it to mean “social apparatus” and “regime of practice”, both of which indicate an ordering of social practices that are infused with a particular “strategic disposition” [74,75]. The “dispositif” lens considers the relationships between the various elements in that “strategic disposition” in terms of relations of knowledge (discourse), power, and subjectivity [75].

Silva Castaneda [76] suggests that the idea of dispositif is nested as a strategic state between the disruptive and stabilizing lines; rather than focusing on the current state of play, it allows for reshuffled initiatives and accompanying relations of knowledge, power, and subjectivity in their appropriate dispersion, meaning that a strategy needs not be reduced to a particular set of relations. Through this lens, a community-level sustainability dispositif based on the microfinance strategy requires a move beyond the problems surrounding critical approaches based on economic relations. As dispositif allows for a less programmatic approach by conceptualizing development as a shifting coagulation of elements that exhibit certain continuities and discontinuities with previous formation [72], a reconfiguration of developmentalism through the rise of NGOs is tenable [77]. Therefore, a shift in the existing CBE paradigm is permeable with the inclusion of ecological objectives. This shift allows for NGOs to be in the dispositif locus, redeploying entrepreneurial subjectivity and institutions within the conventional microfinance scheme—thereby redirecting developmentalism toward achieving local sustainability.

NGOs can achieve this sustainability goal through environmental lending or, more particularly, ES-supportive lending to a community, group, or individual entrepreneur. The primary operational tasks involve defining and determining green ventures, supply and adoption of green technologies, knowledge, affordability, and viability. The emphasis in greening efforts should be on convincing local entrepreneurs of the constraints of the natural environment, the high market demand for green and organic products, and the availability of technical and financial assistance from intermediary organizations. Further, to avoid the initial market distortions and inefficiency and to increase environmental awareness, NGO or intermediary assistance should consist of an aid bundle with loans and grants to increase environmental awareness and develop and diffuse environmentally friendly technologies.

Innovative entrepreneurial strategies built on local strengths can help reorder people’s relationships with local ecosystems, restore community well-being, and enhance local sustainability [78]. The enterprises must be strengthened with management capacity to adopt and manage the new approach. Although this will require multiple stakeholders to work jointly toward the goal, the initial and most instrumental role must be played by the NGO-MFI as the key development partner. This conceptual schema of this modality is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Social–ecological model of community-based entrepreneurship (CBE).

Classic developmentalism has been economistic rather than integrated—largely missing the social and ecological elements. Its top-down and macro-scale nature is characteristically inept at effectively addressing the causes of underdevelopment at the community level. Microcredit guru Prof. Yunus [79] mentions that these development theories are half-done, as even still, half of people globally survive with less than USD 2 a day; the historical paradigms of development have systematically led to a “homogenocene” (Coversi & Posocco, 2024 [80]). Counter to these, the social–ecological model of CBE illustrated in this article not only shifts a community-level developmentalism but also offers an opportunity for decolonizing climate change response (David, 2024 [81]).

6. Discussions and Conclusions

In light of the persistent influence of colonial epistemologies on prevailing development paradigms, it is imperative that community-based enterprises (CBEs) in the Global South consciously disengage from the pervasive effects of indoctrinated developmentalism. This concept encapsulates the imposition of Western-centric models of growth, sustainability, and resource governance, which frequently marginalize indigenous knowledge systems and undermine community autonomy.

The broader discourse on development and coloniality, notably articulated by scholars such as Escobar [43,77], compels a critical re-evaluation of development from the perspective of those who have historically been subjected to asymmetrical power relations. Escobar [6] asserts that “the problem is not just the failure of development but the nature of the development discourse itself” (p. 5), highlighting the urgent need for alternatives that are organically rooted in community contexts rather than imposed through externally defined objectives.

Within this framework, the decolonization of grassroots mentalities—especially among local entrepreneurs and community actors—demands a bottom-up approach that is firmly grounded in local agency and epistemic sovereignty. This evolution is evidenced by the transition from individualistic, efficiency-driven methodologies to more collective, commons-oriented CBE structures. Rather than representing a rigid methodological rupture, this shift signifies an ongoing conceptual and ethical transformation that reconceptualizes CBEs as integral components of relational, participatory, and place-based practices.

Movement-informed approaches—including ecovillage design, indigenous resurgence, and solidarity economies—further reinforce this transition. As articulated by Manzini [82], these frameworks present “social forms capable of combining autonomy and collaboration, local rootedness and global openness” (p. 60), thereby enabling CBEs to function not merely as economic entities, but as catalysts for sociocultural transformation grounded in mutual support and community well-being.

The state of play in development efforts, which can be termed “development dispositif”, was mostly indoctrinated by many theories, hypotheses, strategies, and models. Nevertheless, developmentalism has always been dynamic and, to some extent, experimental by nature. Over time, development policies, especially in the post-colonial decades, have been marked by frequent changes and shifts. Development strategies expanded focus: for example, from industrialization first to balanced growth, economic development to economic and social development, GNP growth strategy to poverty alleviation, and lately from development to sustainable development.

Contemporary developmentalism is faced with the challenges of managing ecosystem services, alleviating poverty, and linking problems and actions locally. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) has explicitly brought forth the gravity and significance of managing ecosystems for achieving qualitative development or human well-being. Although arguments that the development effort needs to transcend the benefits at the community level have become more potent, hardly any other intervention strategy has gained as widespread popularity as microfinance mechanisms. The CBE modality out of NGO-MFI facilitation is viewed as an approach that is entrepreneurial, bottom-up, gendered, and a social capital builder. With its economic and social contributions, the strategic shift through the inclusion of ecological objectives ensures its contribution to local sustainability.

Since dispositif enables a less programmatic approach by conceptualizing development as a coagulation of elements that exhibit certain continuities and discontinuities with previous formations, the inclusion of the ecological management principle within the microfinance strategy is permeable within the framework. With the microentrepreneurship approach being an instrument for development with household, group, or community organizations as subjects for developmentalism, unlike the traditional top-down approaches, sustainability at the community level would be ensured through the new social–ecological model of community-based entrepreneurship.

Author Contributions

A.K.M.S. is the lead author of the paper, while H.M. is the co-author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out under a funded project entitled “Green Microfinance Strategy for Entrepreneurial Transformation: Supporting Growth and Responding to Climate Change”. The author received financial support for this study from the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), UK under Private Enterprise Development in Low Income Countries scheme (Grant # PEDL-ERG, 1752). The first author also acknowledges research seed funding from Memorial University of Newfoundland (MUN) for his community-based entrepreneurship project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBE | community-based enterprise |

| NGO | non-governmental organization |

| MFI | microfinance institution |

| MDG | Millennium Development Goals |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| MA | Millennium Ecosystem Assessment |

References

- Bello, A.D. Navigating Beyond Economic Growth: A Holistic Approach to Development and Equality in Public Policy—Demystifying the Axiom “A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats”. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 12, 533–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.R., Jr.; Hoynes, H.W.; Krueger, A.B. Another Look at Whether a Rising Tide Lifts all Boats; Working Paper No. 8412; The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER): Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schickele, R. Agrarian Revolution and Economic Progress; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T. Requiem or new agenda for Third World studies? World Politics 1985, 37, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C. Understanding Economic Development: A Global Transition from Poverty to Prosperity? Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidullah, A.K.M.; Venema, H.D.; Haque, C.E. Shifting developmentalism vis a vis community sustainability: Can Integration of ecosystem goods and services with microcredit create a local sustainability dispositif? Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 2, 1703–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan-Parker, D.; Patel, R. Voices of the Poor: Can Anyone Hear Us? World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, G.M.; Warner, W. Microcredit as a grass-roots policy for international development. Poli. Stud. J. 2001, 29, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainability. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C. Community development and micro-enterprises: Fostering sustainable development. Sust. Dev. 2000, 8, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.M.; Khandker, S.R.; Cartwright, J. Empowering women with micro-finance. Evidence from Bangladesh. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chng 2006, 54, 791–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Locker, L.; Nugent, R. Microcredit, social capital, and common pool resources. World Dev. 2002, 30, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidullah, A.K.M. Community-Based Developmental Entrepreneurship: Linking Microfinance with Ecosystem Services. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidullah, A.K.M.; Haque, C.E. Environmental orientation of small enterprises: Can microcredit-assisted microenterprises be “green”? Sustainability 2014, 6, 3232–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbecke, E. The Evolution of the Development Doctrine, 1950–2005; UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marangos, J. What happened to the Washington Consensus? The evolution of international development policy. J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrison, C.R. A Comparison of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Community Development Interventions in Rural Mexico: Practical and Theoretical Implications for Community Development Programmes; Government Document Reports of the Findings of a Field Research Project; University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D. Development discourse as hegemony: Towards an ideological history—1945–1995. In Debating Development Discourse: Institutional and Popular Perspectives; Moore, D.D., Schmitz, G.G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1995; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, J.R. Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.T. From nation-building to state-building: The geopolitics of development, the nation-state system and the changing global order. Third World Qtrly. 2006, 27, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.E. From Marshall Plan to Debt Crisis: Foreign Aid and Development Choices in the World Economy; Univ of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. The big push, natural resource booms and growth. J. Dev. Econ. 1999, 59, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkse, R. The Theory of Development and the Idea of Balanced Growth. In Developing the Underdeveloped Countries; Mountjoy, A.B., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1971; pp. 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow, W. (Ed.) The Economics of Take-Off into Sustained Growth; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1963; pp. 1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Leibenstein, H. Economic Backwardness and Economic Growth; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, J.C.H.; Ranis, G. Development of the Labor Surplus Economy; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Corbridge, S. Thinking about development. Reg. Stud. 1998, 32, 790–791. [Google Scholar]

- Chenery, H.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Duloy, J.H.; Bell, C.L.G.; Jolly, R. Redistribution with Growth; Policies to Improve Income Distribution in Developing Countries in the Context of Economic Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. Pro-poor growth in a globalized economy. J. Int. Dev. 2001, 13, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissanke, M. Pro-poor Globalisation: An Elusive Concept or a Realistic Perspective? Inaugural Lecture Series; SOAS University of London: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Constanza, R.; Patten, B.C. Defining and predicting sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 15, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, T.; John, F. What is sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Economic sustainability of the economy: Concepts and indicators. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, V. Recovering the real meaning of sustainability. In The Environment in Question: Ethics and Global Issues, 1st ed.; Cooper, D., Palmer, J.A.E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. (Eds.) Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; p. 393. [Google Scholar]

- Handl, G. Declaration of the United Nations conference on the human environment (Stockholm Declaration), 1972 and the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992. United Nations Audiov. Libr. Int. Law 2012, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.; Jorgan, R. The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, G.O. The Global 2000 Report to the President of the US: Entering the 21st Century: The Technical Report; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup, R.L.; Jane, S.S. The Resourceful Earth. Intercoll. Rev. 1985, 20, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- World Wildlife Fund. World Conservation Strategy: Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1980; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our common future—Call for action. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Construction nature: Elements for a poststructuralist political ecology. Futures 1996, 28, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Benjaminsen, T.A.; Brown, K.; Svarstad, H. Advancing a political ecology of global environmental discourses. Dev. Chang. 2001, 32, 681–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridger, J.C.; Luloff, A.E. Toward an interactional approach to sustainable community development. J. Rural. Stud. 1999, 15, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanarella, E.J.; Levine, R.S. Does sustainable development lead to sustainability? Futures 1992, 24, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngberg, G.; Harwood, R. Sustainable farming systems: Needs and opportunities. Amecn. J. Alt. Agri. 1989, 4, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Common-Property Resources: Ecology and Community-Based Sustainable Development; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Luloff, A.E.; Swanson, L.E. Community agency and disaffection: Enhancing collective resources. In Investing in People: The Human Capital Needs of Rural AMERICA; Beaulieu, L.J., Mulkey, D., Eds.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bridger, J.C. Power, Discourse and Community: The Case of Land Use. Ph.D. Thesis, Penn State University, University Park, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, K.P. The community in Rural America; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, W.V.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Hassan, R.; et al. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA); Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Institute. World Resources, 2005: The Wealth of the Poor: Managing Ecosystems to Fight Poverty; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 11. Available online: http://pdf.wri.org/wrr05_lores.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Brauman, K.; Daily, G.; Duarte, T.; Harold, A. The nature and value of ecosystem services: An overview highlighting hydrological services. Annl. Rev. Env. Res. 2007, 32, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. Community resilience, policy corridors and the policy challenge. Land. Use Pol. 2013, 31, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlewood, P.; Greg, M. Ecosystems, Climate Change and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs); World Resource Institute (WRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: http://www.wri.org/publication/ecosystems-climate-change-millennium-development-goals (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Shahidullah, A.K.M. ‘Community-based adaptive entrepreneurship’ addressing climate and ecosystem changes: Evidence from a riparian area in Bangladesh. Climate Risk Mgmt. 2023, 41, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.P.; Barbara, A.K. Community-based enterprises: Propositions and cases. Entrl. Bona. 2002, 16, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapa, W.; Al Mamun, A.; Ibrahim, M. Development initiatives, micro-enterprise performance and sustainability. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2018, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoux, L. Women’s empowerment versus sustainability? In Women and Credit. Researching the Past, Refiguring the Future; Beverly, L., Ruth, P., Gail, C., Eds.; Berg: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Afrin, S.; Islam, N.; Ahmed, S.U. A Microcredit and rural women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: A multivariate model. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 16, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowla, A. In credit we trust: Building social capital by Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. J. Socio-Econ. 2006, 35, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K. Social capital, microfinance, and politics of development. Fam. Econ. 2002, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswami, K. Microfinance and the Human Condition: A Bottom-Up Approach towards Promoting Freedom and Development. Soc. Sci. 2010, 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.A.; Dunn, E. Household Economic Portfolios; Management Systems International: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S. Microcredit Won’t Make Poverty History. The Guardian. 17 October 2006. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2006/oct/17/businesscomment.internationalaidanddevelopment (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Foose, L. The double bottom line: Evaluating social performance in microfinance. MicroBanking Bull. 2008, 17, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A.K. Quality of Life: India vs. China. N. Y. Rev. Books 2011, 58, 44–47. Available online: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/05/12/quality-life-india-vs-china/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Alves, J.L.S.; de Medeiros, D.D. Eco-efficiency in micro-enterprises and small firms: A case study in the automotive services sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Collins, L.; Israel, E.; Wenner, M. The Missing Bottom Line: Microfinance and the Environment. Green Microfinance LLC, Document Prepared for The SEEP Network Social Performance Working Group Social Performance MAP. 2008. Available online: https://dfedericos.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/missing-bottom-line_microfinance-and-environment_seep-2008-3.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Shahidullah, A.K.M.; Haque, C.E. Green microfinance strategy for entrepreneurial transformation: Validating a pattern towards sustainability. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2015, 26, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigg, M. Empowering NGOs: The microcredit movement through Foucault’s notion of dispositif. Altern. Glob. Local. Political 2001, 26, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977; Gordon, C., Ed.; Pantheon: Paramus, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen, K. Doing without state and civil society as universals: ‘dispositifs’ of care beyond the classic sector divide. J. Civ. Soc. 2008, 4, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G. What is a Dispositif? In Michel Foucault Philosopher; Amstrong, T.J., Ed.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Castaneda, L.A.; Nathalie, T. Sustainability standards and certification: Looking through the lens of Foucault’s dispositif. Glob. Netw. 2016, 16, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Imagining a post-development era? Critical thought, development and social movements. Soc. Text. 1992, 31, 20–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidullah, A.K.M.; Choudhury, M.U.I.; Haque, C.E. Ecosystem changes and community wellbeing: Social-ecological innovations in enhancing resilience of wetlands communities in Bangladesh. Local. Env. 2020, 25, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. Creating a World Without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Conversi, D.; Posocco, L. Homogenocene: Defining the Age of Bio-cultural Devastation (1493–Present). Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.O. Decolonizing climate change response: African indigenous knowledge and sustainable development. Front. Sociol. 2024, 9, 1456871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).