Abstract

Entrepreneurship has long been a key driver of economic development across various countries. Investigating the determinants of entrepreneurial behaviour is essential for making a meaningful contribution to sustainable development. This study investigated the determinants of entrepreneurial behaviour among university of technology and TVET college students in South Africa, utilising the modified theory of planned behaviour. Specifically, the study explored how risk-taking propensity, financial and non-financial support, media, and gender influence perceived behavioural control, entrepreneurial intention, and behaviour. Additionally, the study tested the direct effects of perceived behavioural control on both entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial behaviour, as well as the direct effect of entrepreneurial intention on entrepreneurial behaviour. An online, structured, self-administered questionnaire was utilised to gather data from 496 finalyear diploma students at a university of technology and a TVET college, using a convenience sampling technique. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was applied to analyse the data and test the postulated hypotheses. The findings revealed that non-financial support positively affected entrepreneurial intention, perceived behavioural control, and entrepreneurial behaviour, while financial support did not. Risk-taking propensity significantly influenced perceived behavioural control, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial behaviour. The results revealed that the gender was negatively related to perceived behavioural control, and female students exhibited lower perceived behavioural control than their male counterparts. However, gender showed no significant association with entrepreneurial intention or entrepreneurial behaviour. Media had a positive influence on both entrepreneurial intention and perceived behavioural control but did not significantly affect entrepreneurial behaviour. Additionally, both entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial behaviour were positively influenced by perceived behavioural control, while entrepreneurial intention also was positively associated with entrepreneurial behaviour. These findings underscore the critical role of fostering a supportive entrepreneurial environment in shaping entrepreneurial behaviour. This study provides valuable insights for policymakers and educators to cultivate an environment that supports students in developing as entrepreneurs. The results can inform policymakers in implementing support interventions aimed at enhancing entrepreneurial capacity among the youth. Promoting entrepreneurship is vital in achieving sustainable development goals through job creation and poverty alleviation.

1. Introduction

The vital role of entrepreneurship in driving economic growth and serving as a catalyst for global economic development is widely recognised [1,2]. Thus, efforts to stimulate entrepreneurship can contribute to sustainable development through job creation, poverty reduction and economic development [3,4]. In view of rising unemployment rates, entrepreneurship offers an avenue to create decent work opportunities and a viable means for stimulating economic growth [4,5].

For entrepreneurship to meaningfully contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an understanding of the factors that shape entrepreneurial behaviour (EB), particularly among students who represent the youth who are vulnerable groups affected by high unemployment rates, is crucial. This study aims to examine the effect of financial support (FS), non-financial support (NFS), media (MD), risk-taking propensity (RTP), and gender on entrepreneurial intentions (EI), perceived behavioural control (PBC), and EB among South African university and TVET college students, using the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as a guiding framework. Additionally, the study seeks to determine the direct effects of EI and PBC on EB.

In South Africa, the government has introduced a series of support programmes aimed at promoting entrepreneurship in response to the persistently high unemployment rate, which currently stands at 33.5% [6]. Despite these efforts, the total entrepreneurial activity (TEA) saw a significant decline, dropping from 17.5% in 2021 to 8.5% in 2022, before slightly rebounding to 11.1% in 2023 [6]. Of particular concern is the low participation of women (9.7%) compared to men (12.7%) in the early stages of business development [7], reflecting a persistent gender gap in entrepreneurship. This gap is driven by barriers such as limited access to resources, lower confidence levels, lack of mentorship, and entrenched gender norms that discourage women from pursuing entrepreneurial ventures. These statistics highlight the urgent need for policymakers to create a supportive environment that can stimulate entrepreneurial activity to help in reducing the unemployment rate.

Existing literature emphasises the importance of both entrepreneurial intentions (EI) and growth intentions in the formation of new ventures and the expansion of established businesses [8,9,10,11]. However, Ajzen [12] contends that perceived barriers associated with starting a business often hinder the translation of EIs into actual behaviour. This suggests that individuals can only pursue their EIs to the extent that they have access to critical resources, such as financial support (FS) to launch a business and non-financial support (NFS) to effectively operate and manage a business [12]. Research evidence shows that supportive environments, encompassing the provision of both financial and non-financial resources, as well as positive mass media messages about entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in general, stimulate EIs and foster increased entrepreneurial activity [13,14,15,16,17]. Thus, a supportive environment in which FS and NFS are readily available to facilitate the entrepreneurial process, complemented by positive media narratives, portrayals, and messages about entrepreneurship, can help both potential and existing entrepreneurs to overcome the barriers associated with starting and growing a business [12,14,18].

While the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is widely used to predict EIs and behaviour, a growing consensus among scholars suggests extending it with additional antecedents to better understand the factors influencing these outcomes [9,11,15]. For instance, exploring the impact of NFS, FS, media (MD), and gender on EI and behaviour could yield valuable insights for policymakers and resultant interventions to help foster entrepreneurial activity. The inclusion of RTP, FS, NFS, media (MD), and gender is grounded in their relevance to understanding EB within the South African context. RTP and gender capture individual-level differences, which have been found to be associated with entrepreneurship, while FS, NFS, and MD represent contextual influences that can shape both PBC, EI and behaviour, especially in environments marked by uncertainty and limited resources. These variables can also contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by fostering inclusive participation in entrepreneurship [5,19], equipping aspiring students with essential knowledge and skills [20], encouraging the involvement of underrepresented groups in start-up activities, particularly young women [19], and providing financial resources and support for businesses to scale up and implement sustainable practices [4,5]. The TPB is well-suited for this study, as it identifies EI and PBC as key predictors of EB [12], and its extension with relevant individual and contextual factors can strengthen its predictive power and enrich our understanding of the drivers of EB.

Central to entrepreneurship are individuals who assume risks and actively participate in entrepreneurial activities [21,22]. It is proposed that individuals with high risk-taking propensity (RTP) are likely to form EIs and engage in entrepreneurial behaviour (EB) [23], as entrepreneurship is an intentionally planned behaviour in nature [9,12]. RTP refers to an individual’s willingness to undertake action, such as starting a business, in which outcomes are uncertain [18,24]. In recent years, studies have maintained that to improve entrepreneurial activities in countries, efforts should be directed at improving the entrepreneurial environment and fostering a culture that encourages risk-taking behaviour [21,25].

Embarking on an entrepreneurial journey to establish a new business can be risky, given the high failure rate associated with new ventures [21,26]. Entrepreneurs make decisions to create new ventures in constantly changing environments, which make the outcomes of their decisions uncertain [27]. Thus, uncertainty can prevent entrepreneurial action by creating hesitancy, indecisiveness and procrastination in the mind of the entrepreneur that results in missed opportunities [27]. However, individuals who have high RTP are distinguished from non-entrepreneurs due to their willingness to bear the risk and tolerance for uncertainty [28]. Entrepreneurs are believed to be individuals who assume various risks, including psychological, social, and financial, during the establishment of new firms [26]. Some studies posit that individuals with a high RTP are more likely to discover opportunities and engage in entrepreneurship rather than pursue traditional employment [29,30]. Prior research indicates that high RTP is associated with stronger EIs [31]. These results imply that the propensity for risk-taking remains a crucial component in research to understand why some individuals choose to pursue the entrepreneurial career option while others do not [32,33]. Therefore, investigating the role of RTP in influencing EI and behaviour is vital to guide policymakers in the design and implementation of interventions that could facilitate entrepreneurship development [34,35].

EB follows the formation of EI, as intentions predict human behaviour [12,36,37]. Most studies have used the TPB to determine the factors that drive the formation of EI (for example, [35,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]). However, there are few studies that have used the TPB to test the impact of EI and perceived behavioural control (PBC) on EB as proposed by Ajzen (for example, [45,46,47]). The limited research on the impact of EI and PBC on EB calls for more research to help uncover these links so that policymakers could direct support efforts accordingly to stimulate EB.

Although the TPB has served as a foundational framework for understanding and predicting EI and subsequent behaviour, this study extends the model by incorporating RTP, FS, NFS, MD, and gender as additional antecedents. This provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing EB. While EI and PBC have been extensively studied, limited empirical research has examined how EI and PBC shape EB collectively within a single framework. Such an integrated approach is essential for understanding the impact of EI and PBC on EB and for the advancement of the TPB in the field of entrepreneurship. Furthermore, most existing studies have focused predominantly on university students, with relatively little attention given to students in TVET institutions. Addressing this gap is critical, as TVET students represent a distinct and often underserved population in entrepreneurship research. This study contributes to the literature by exploring these relationships among both TVET and university students in South Africa, offering novel insights into the pathways leading to EB.

The following sections will delve into the literature review, research procedures, and key findings of the study. In conclusion, the paper will reflect on the results, acknowledge the study’s limitations, and explore the broader implications, while also suggesting potential avenues for future research.

2. Review of Literature and Hypothesis Formulation

2.1. Financial Support (FS) and Non-Financial Support (NFS)

The recognition or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities through environmental scanning constitutes the first step in the process of launching a new venture [48,49]. The decision to exploit these opportunities typically follows the formation of EIs [9,12] and is strongly influenced by the perception of a supportive environment [50,51]. However, exogenous obstacles pose significant challenges for potential entrepreneurs in their efforts to exploit the identified opportunities [52]. Addressing these barriers could effectively promote entrepreneurial behaviour by stimulating EIs. Thus, the perceived availability and access to both FS and NFS can boost individuals’ confidence in their own entrepreneurial capabilities, stimulate EIs, and foster entrepreneurial behaviour [53,54]. This is because FS and NFS enable entrepreneurs to acquire resources, identify opportunities, and promote entrepreneurial alertness among potential and existing entrepreneurs [51], and as a result, facilitate the establishment of new ventures and improve their performance [49].

In South Africa, the government, through the Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition (the DTIC), has established several support agencies to create a supportive entrepreneurial environment and facilitate small business growth through FS and tailored NFS [55]. NFS encompasses tangible and intangible resources vital for starting and managing a business. This includes business development services, mentoring, market access, incubation programmes, and sector-focused support for women and youth enterprises. [56,57]. Additionally, NFS consists of business and concept development support, educational support [15], structural support [16], university entrepreneurship support [58], access to physical infrastructure, and opportunities for education and training [59]. FS, on the other hand, involves access to equity, debt, grants, and subsidies for new and growing businesses [60]. Perceived difficulty in accessing both types of support can hinder entrepreneurial success by increasing perceived risks and reducing the attractiveness and feasibility of starting a business [61]. These support programmes are therefore deemed critical for addressing the challenges associated with establishing and managing new businesses [62,63,64].

Previous research that has examined the role of FS in facilitating entrepreneurship has generated mixed findings [59,60,61,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. These inconsistencies may be attributed to contextual factors such as economic conditions, effectiveness of institutional support, and variations in research design, sample characteristics, and measurement approaches. For instance, Narmaditya et al. [59], Saoula et al. [66], and Ahmad [61] found a positive relationship between access to FS and EIs. Conversely, other studies have found that access to FS on EIs was not associated with EI [67,68,69]. Additionally, some studies observed that access to FS is positively associated with PBC [60,64,65], while others reported an insignificant relationship [70].

Similarly, studies investigating the influence of NFS on entrepreneurship have also yielded inconsistent results [13,15,16,55,58,59,67]. Research by Ebewo and Nesamvuni [13], Su et al. [15], Narmaditya et al. [59], Trang and Doanh [16], and Lu et al. [58] suggests that NFS positively influences both EI and PBC. However, other studies have found no significant impact of NFS on EI [55,67]. These findings suggest that while FS and NFS can enhance entrepreneurial capabilities, stimulate EIs, and foster EB, their influence may vary from one population to another. Hence, their effects should be studied in specific contexts to facilitate the design and implementation of interventions that address the real needs of both existing and potential entrepreneurs. Drawing from the above discussion, it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

FS exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EI, PBC, and EB.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

NFS exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EI, PBC, and EB.

2.2. Risk-Taking Propensity (RTP) and Gender

Entrepreneurs are distinguished from non-entrepreneurs based on their level of risk-taking tendency, with the former displaying higher RTP than the latter [71,72]. This suggests that high RTP propels individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities and vice versa [73]. The pursuit of an entrepreneurial career option is dependent on one’s willingness to act in situations in which the outcomes are uncertain [18,24]. Constant changes in the volatile business environment create unpredictability regarding the success of one’s own entrepreneurial efforts. Individuals with high RTP have the tendency to commit resources to projects that can generate high returns with inherent high costs of failure; engage in projects with uncertain outcomes; and are more likely to venture into the unknown paths [74]. RTP enables entrepreneurs to study market conditions and facilitates new product success [74]. This is corroborated by Kuckertz et al. [75] who discovered that risk-taking is positively related to opportunity recognition and exploitation, particularly among entrepreneurs with psychological traits such as high self-confidence and supported by access to FS and NFS such as mentorship, networks, and training, which help reduce uncertainty and increase their confidence in pursuing risky opportunities [51]. Within the TPB framework, RTP primarily influences both PBC and EI [21,76], as individuals with higher RTP are more confident in their ability to control outcomes and are more likely to form intentions to start a business.

Previous studies indicate that RTP has a significant influence on EI [76,77]. Individuals who display high RTP tend to develop intentions to launch their own business [21,29,30,78]. With regards to the antecedents of EI, positive associations have been found between RTP, PBC and entrepreneurial self-efficacy [21,79]. On the contrary, it is reported that risk aversion could negatively affect PBC and perceptions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy [80]. Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

RTP exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EI, PBC, and EB.

Previous studies on gender differences in EIs and participation in entrepreneurial activity reveal that women tend to demonstrate lower EIs [81,82] and are underrepresented in entrepreneurship compared to men [83]. This disparity can be attributed to differences in perceptions of entrepreneurship between males and females. For example, Mansour [81] discovered that females tend to display less confidence in initiating startup activities than males. Similarly, Hill et al. [83] found that females perceive their entrepreneurial capabilities and the entrepreneurial environment less favourably and exhibit lower perceptions of market opportunities, need for achievement, and risk-taking tendencies. Furthermore, Malebana [84] found that males exhibited significantly higher intentions to pursue entrepreneurship, perceived entrepreneurial capabilities, and entrepreneurial self-efficacy than their female counterparts. From these studies, it is evident that gender disparities in EIs and participation in entrepreneurial activities are influenced by both perceptual and structural factors. In addition to low confidence in their own entrepreneurial ability, women often face specific barriers such as fear of failure, financial exclusion, and limited access to mentorship and entrepreneurial networks, which further hinder their participation in entrepreneurial activities [7].

The effect of gender on EIs, perceived entrepreneurial capability, and behaviour has been examined in previous studies [84,85,86,87,88]. For example, in South Africa, Malebana [84] reported a weak relationship between gender, EI and PBC. Similarly, Maes et al. [85] and Palupi and Santoso [86] found that the effect of gender on EI is mediated by PBC and that gender also has a direct effect on PBC. Dubey and Sahu [87] observed a statistically significant effect of gender on EIs, whereas Slamet et al. [88] found no such effect. These contradictory findings may be attributed to varying contextual factors across studies. For instance, cultural norms and societal attitudes toward gender roles may influence how men and women perceive entrepreneurship in different regions. Given the varying results from previous studies, it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Gender exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EI, PBC, and EB.

2.3. Media (MD) and Entrepreneurial Behaviour (EB)

Few studies have investigated the role of the media in shaping EIs [17,89,90]. Based on the social cognitive theory of mass communication, it is argued that the media can shape societal attitudes, beliefs, intentions, and actions [91]. Media can be categorised into print, broadcast, and television systems [89]. Media facilitates entrepreneurship by shaping public perceptions [17], sharing valuable information, and highlighting success stories through positive messaging [90], coverage of entrepreneurial achievements, and business-focused reality programmes [89]. According to Laguía and Moriano [17], the media can help in creating an entrepreneurial culture. The depiction of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in the media shapes perceptions of social legitimacy, value, and desirability of pursuing the entrepreneurial career option [17,89,90]. Stories about successful entrepreneurs in the media provide individuals with symbolic role models whose successes can inspire, guide, and be emulated [35,92]. Therefore, the extent to which entrepreneurs are depicted positively in the mass media and favourably discussed within society is likely to have a positive influence on EIs and stimulate entrepreneurial activity [17,92].

Theoretical explanations suggest that media messaging affects EIs and entrepreneurial behaviour by altering individuals’ perceptions of entrepreneurship’s viability, desirability, and social legitimacy [17]. Media portrayals often create an aspirational image of entrepreneurs, providing role models that can motivate individuals to pursue entrepreneurial ventures [89]. Findings of prior research suggest that media can be a powerful tool for influencing both EIs and EB [17,35,92,93]. For example, Mothibi and Malebana [35] found that media was positively related to both EI and PBC. Similarly, Laguía and Moriano [17] discovered that the perceived social legitimacy of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in the media was significant and positively related to EI as well as PBC. Other studies have found that positive media coverage of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs is positively associated with EI [92,93,94]. In contrast, Levie, Hart and Karim [90] found that media, in the form of televised business reality programmes, was not significantly related to EI. These findings suggest that media effects can vary depending on individual characteristics, such as education level, gender, or economic background. Individuals with higher education may be more receptive to entrepreneurial messages, while gender and economic background might influence the types of opportunities perceived as attainable or desirable. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Media exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EI, PBC, and EB.

EB is understood as those tangible and observable actions undertaken by individuals to start and grow a new business [95,96]. Engagement in EB involves the performance of activities such as identifying and exploiting opportunities, committing resources, securing financing, planning, hiring, and training of employees with a view to launching and growing a business [95,97,98,99].

The TPB postulates that PBC reflects an individual’s self-efficacy or ability to perform a given behaviour and can influence behaviour [12,36], including entrepreneurial behaviour, both directly and indirectly through its effect on intention [36]. While intention alone can predict behaviour, PBC serves as an additional predictor, enhancing entrepreneurial actions by increasing the perceived feasibility of starting and managing a business [12]. PBC is particularly influential in situations where external constraints exist, and it enhances the feasibility of entrepreneurial actions, thus influencing both EI and EB [36]. Ajzen’s [36] TPB has been employed in numerous research studies in various contexts to test the association between EI, PBC and EB [11,34,45,47,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]. Findings of these studies indicate that EB could be explained by both EI and PBC or by either one of these variables. For instance, studies by Farooq [102]; Valencia-Arias and Restrepo [108]; Akter and Iqbal [100]; Kibler et al. [103]; Nergui [11]; and Doung et al. [101] observed that both EI and PBC had a significant impact on EB, with PBC tending to have a stronger effect on EI than on EB. However, other studies reported that EB was significantly associated with EI only, but not with PBC [45,47,104]. Furthermore, some studies found that PBC indirectly impacted EB through its effect on EI [104,105,106]. The variance in EB explained by the model differed across studies and varied from 19% to 31% [34,103]. Contrary to Ajzen’s [36] view, Tran et al. [107] found that in addition to EI and PBC, attitude towards the behaviour is positively related to EB. These prior studies show that the TPB model can predict business start-up behaviour. The differences in findings across studies could be attributed to contextual factors such as the research setting, sample characteristics, and methodological variations such as data collection methods and measurement instruments, all of which could influence the strength and direction of the relationships between EI, PBC, and EB. Based on the foregoing literature discussion, it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

PBC exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EI.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

PBC exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EB.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

EI exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on EB.

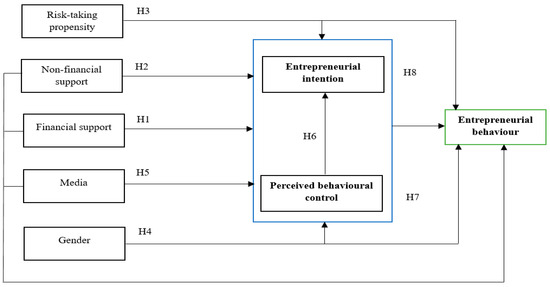

The conceptual model for the study based on the foregoing literature review and hypotheses is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the study. Source: Developed by the authors, drawing on Ajzen’s [32] framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

The study was originally intended to survey all 702 final year diploma students from Tshwane University of Technology (TUT) and Tshwane North TVET College. However, due to the unavailability of some respondents during data collection, a convenience sample of 496 willing students ultimately completed the questionnaire, resulting in a 70.7% response rate. As shown in Table 1, this sample included 271 respondents from Tshwane North TVET College and 225 from TUT.

Table 1.

Demographic details of respondents.

Among the 496 respondents, most (80.4%) were aged 18 to 24 years, followed by 18.2% aged 25 to 34 years and 1.4% aged 35 and above. Regarding gender, 59% of the respondents were female, and 41% were male, indicating that females constituted the majority of respondents.

These institutions were purposefully selected because both are located in Gauteng Province, South Africa’s economic hub and a strategic region for entrepreneurship development. Focusing on final year students allowed the study to capture entrepreneurial intentions and behaviours at a critical transition point from education to the world of work.

Data collection occurred subsequent to receiving ethical clearance from the Tshwane University of Technology Research Ethics Committee and the Department of Higher Education and Training. A structured, self-administered online questionnaire was used to gather primary data relevant to the research objectives. Data were collected between 11 September 2022 and 10 December 2022. Owing to the persistent COVID-19 pandemic, the researcher deemed this method of collecting data feasible, safe, economical, efficient, and convenient for the respondents. The research participants accessed the questionnaire using a web browser with a hyperlink. The participants were briefed on the research’s purpose and were requested to complete the questionnaire voluntarily. Anonymity was assured for all participants.

3.2. Instruments and Measures

A structured, self-administered online questionnaire was used to gather data. The questionnaire was based on EI and PBC measures from Liñán and Chen [109] and previously tested and validated by Malebana [110] in South Africa. Measures for RTP were adopted from Karimi et al. [79], Anwar and Saleem [21], and Vogelsang [111]. Data on PBC, EI, and RTP were collected using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In contrast, data on EB were collected using nominal (Yes/No) questions. These items were adapted from Kautonen et al. [34] and Farooq [102] and had been validated in subsequent studies by Yi [112], Li et al. [113], and Mahmood et al. [105]. The use of nominal items was consistent with the original operationalisation in these studies, which focused on the presence or absence of specific entrepreneurial actions. The adoption of previously validated measures enhanced the reliability and content validity of the questionnaire. Furthermore, to enhance contextual alignment, we conducted a pretest of the questionnaire before full deployment. Feedback from this process was used to refine the wording of certain items to improve clarity and cultural relevance for students in the Gauteng region.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Model Measurement

Assessment of the measurement model followed the four methods outlined by Hair et al. [114], using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS4 software (v.4.0.8.3). First, the factor loadings of the indicators were evaluated based on the recommendation to accept values greater than 0.50 [114,115]. After eliminating 13 items with poor external loadings, Table 2 shows that the remaining factor loadings exceed the recommended threshold of 0.50. The retained items continued to load strongly on their intended factors and maintained acceptable internal consistency.

Table 2.

Reliability and convergent validity assessment.

The reliability of the model was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) scores. Hair et al. [114,115] suggest that values ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 indicate satisfactory to good reliability of constructs. As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR) values for the latent variables exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.771 to 1.000 and composite reliability ranging from 0.853 to 1.000. These results confirm that the survey questions measured the intended constructs correctly, and therefore the data were reliable to allow for further analysis.

Convergent validity was assessed by evaluating the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct, using the 0.50 threshold value recommended by Sarstedt et al. [116]. In this study, AVE values ranged from 0.580 to 1.000, indicating that convergent validity was achieved.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [114,117] and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio [115]. The HTMT values should remain below the recommended threshold of 0.85 [116] to confirm that the constructs demonstrate strong discriminant validity. Regarding the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the square root of each construct’s AVE should exceed the correlations with other latent constructs [117]. Table 3 reveals that all AVEs on the diagonals exceeded the corresponding row and column values, confirming discriminant validity. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, all HTMT ratio values were below the 0.85 threshold, further supporting discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Assessment of discriminant validity using the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 4.

Assessment of discriminant validity using HTMT.

4.2. Structural Model

The structural model was assessed by identifying collinearity issues, evaluating the significance and relevance of the model relationships, and analysing its explanatory and predictive power. To detect potential collinearity issues, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were examined. Ideally, VIF values should be below the 5.0 threshold, and according to Hair et al. [115], values of 3.0 or lower indicate minimal collinearity risk. As shown in Table 2, all VIF values are below 5.0, confirming that common method bias was successfully addressed through the overall collinearity test approach.

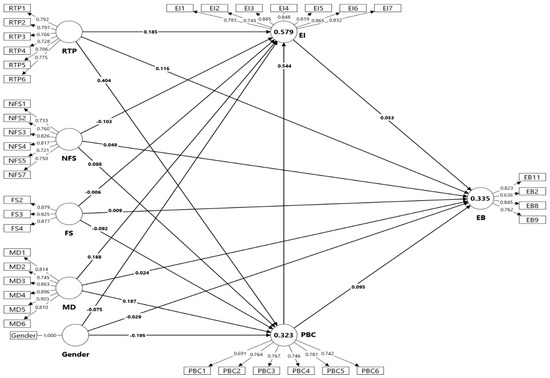

R2 was used to assess the predictive power of the model and to determine the variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variables [110,111]. Figure 2 shows that the exogenous variables collectively explain 57.9% (R2 = 0.579) of the variance in EI. Additionally, the exogenous variables account for 32.3% (R2 = 0.323) of the variance in PBC and 33.5% (R2 = 0.335) of the variance in EB.

Figure 2.

Results from the structural model.

The effect size (f2) measures the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable by analysing changes in the R-squared value [114]. In this study, the effects of exogenous latent variables ranged from no effect to small, medium, and large effects in some cases, in line with limits explained by Sarstedt et al. [116]. For this study, model fitness through f2 was measured, and the values obtained for each path are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Assessment of relative impact using f2.

The predictive relevance of the structural model was assessed based on Q2 values. With Q2 values ranging from 0.111 to 0.346, the results in Table 6 show that the endogenous latent constructs possessed adequate predictive relevance.

Table 6.

Assessment of predictive relevance using Q2.

4.3. Path Coefficients for Hypotheses Tests

The findings in Table 7 indicate that NFS was positively related to PBC (β = 0.088, p < 0.038), EI (β = 0.103, p < 0.005), and EB (β = 0.049, p < 0.019). These results suggest that non-financial support positively impacts EIs and enhances PBC. Furthermore, the findings indicate that NFS increases the likelihood that individuals will engage in EB. However, the findings also indicate that FS had no effect on PBC (β = −0.092, p < 0.055), EI (β = −0.006, p < 0.866), and EB (β = 0.009, p < 0.624). These findings suggest that FS does not enhance EI and PBC and does not facilitate engagement in EB. The findings provide support for H2, while H1 is rejected.

Table 7.

Findings from hypotheses testing.

Findings show that RTP positively affects PBC (β = 0.404, p < 0.000), EI (β = 0.185, p < 0.000), and EB (β = 0.116, p < 0.000). These findings indicate that individuals with high RTP feel more confident and capable of performing entrepreneurial tasks and are more likely to have strong EIs and create new ventures. These findings highlight that RTP is a critical psychological trait that can influence students to engage in entrepreneurship, which supports H3.

The findings in Table 7 further show that gender was negatively related to PBC (β = −0.195, p = 0.013) and did not have an effect on either EI (β = −0.075, p = 0.218) or EB (β = −0.029, p = 0.415). The results of the multi-group analysis revealed that female students scored lower on PBC (mean = 0.445) than their male counterparts (mean = 0.701). These findings indicate that the strength of PBC can vary depending on the gender of the respondents. Furthermore, the findings suggest that gender does not influence EIs and EB among the respondents, partially supporting H4.

The findings show that MD was positively related to PBC (β = 0.187, p < 0.000) and EI (β = 0.188, p < 0.000), but not with EB (β = 0.024, p < 0.328). These results suggest that positive portrayals of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in the mass media enhance individuals’ confidence in their own entrepreneurial capabilities and EIs but do not have a direct influence on EB. However, while MD plays a vital role in enhancing entrepreneurial confidence and intention, it does not directly influence actual business creation, which partially supports H5.

The findings in Table 7 indicate that PBC positively impacted both EI (β = 0.544, p < 0.000) and EB (β = 0.116, p < 0.000). These findings suggest that individuals with positive perceptions of their own capabilities to act entrepreneurially are more likely to have strong EIs and launch their own ventures. Additionally, the findings show that EI had a positive association with EB (β = 0.053, p < 0.048). These findings suggest that having strong EIs increases individuals’ likelihood of launching their own ventures. Hence, H6, H7 and H8 find support.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of RTP, FS, NFS, MD, and gender on PBC, EI, and EB. Additionally, the study assessed the direct effects of PBC on both EI and EB, as well as the direct effect of EI on EB. The findings revealed that NFS positively influenced EI, PBC, and EB, whereas FS did not have any effect. These results corroborate prior research findings that reported the positive effects of NFS on EI and PBC [13,15,16,58,59]. However, these findings do not support prior research that has found a positive association between FS and both EI [59,61,66] and PBC [60,64,65], while supporting studies that found no significant relationship between FS and EI [68,69] or FS and PBC [70]. These findings suggest that the perceived availability of and access to NFS is vital in shaping EIs, and it can enhance individuals’ confidence in performing entrepreneurial activities and foster EB. On the other hand, the lack of impact from FS on EI, PBC, and EB may be due to limited access caused by bureaucratic hurdles, strict eligibility criteria, and lack of collateral, especially for students. Additionally, low awareness or understanding of available funding programmes may prevent effective utilisation of financial support.

The findings indicate that RTP positively affects PBC, EI, and EB. These results align with previous studies that found that reported the positive effects of RTP on EI [21,29,30,78] and PBC [21,79]. These findings suggest that individuals’ willingness to take risks shapes EI formation and enhances their beliefs in their own capability to execute entrepreneurial tasks.

Gender was negatively related to PBC but showed no effect on EI or EB. The results of the multi-group analysis revealed that female students scored significantly lower on PBC than their male counterparts. The negative effect of gender on PBC suggests that certain gender-related factors may lower students’ PBC. This negative relationship may be attributed to social norms, limited access to entrepreneurial role models, and restricted participation in business networks, all of which can reduce an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform entrepreneurial tasks.

Moreover, the findings of this study further revealed that MD positively influences both EI and PBC but had no effect on EB. These results contradict those of Levie, Hart and Karim [90], who found that media, specifically televised business reality programmes, had no impact on EI. However, the findings align with those of Mothibi and Malebana [35] and Laguía and Moriano [17], who reported the positive effects of MD on EI and PBC. These findings suggest that exposure to positive media stories about entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship can inspire people to view entrepreneurship as a viable career path and enhance their confidence in starting and managing a business. The lack of direct impact of MD on EB may be due to external constraints, such as limited funding, skills, resources, or support, which hinder students from translating their intentions into action.

Additionally, the results indicate that PBC positively affects both EI and EB, while EI had a positive influence on EB. These results corroborate prior research that reported significant impacts of both EI and PBC on EB [11,100,101,102,103,108]. In line with Ajzen’s [36] theory, the findings of this study indicate that the likelihood of performing a given behaviour increases with the degree to which individuals intend to engage in it and perceive themselves as capable of doing so. However, these findings do not concur with those of prior studies that could not find a positive relationship between PBC and EB [46,47,104].

6. Conclusions and Implications

The main findings of this study reveal that NFS positively influenced EI, PBC, and EB, while FS had no significant effect. Additionally, RTP positively impacted EI, PBC, and EB, while gender was negatively related to PBC but showed no effect on EI or EB. Furthermore, MD positively influenced EI and PBC but had no direct impact on EB. Finally, PBC was found to positively affect both EI and EB, with EI also positively influencing EB.

The findings of this study have implications for policymakers and entrepreneurship educators, emphasising the need for interventions aimed at supporting the development of EI and their conversion into EB. Firstly, entrepreneurship education that emphasises the benefits of an entrepreneurial career while integrating sustainability development principles, along with mentorship and experiential learning programmes, can significantly enhance perceived capability and entrepreneurial intention. Secondly, entrepreneurship educators should employ practical teaching methods to provide students with real-life, hands-on experience in starting and running a business, including how to navigate the challenges. Educational institutions should partner with government business support agencies and sustainability-focused organisations to ensure that students have easy access to resources for experimenting with their ideas and to develop sustainable entrepreneurial practices during their studies. This will enhance PBC, as the availability of resources will lessen the foreseeable impediments to the execution of the intended behaviour and ultimately facilitate the implementation of EI. Given the negative effect of gender on PBC, targeted interventions such as mentorship programmes, female-focused entrepreneurship training, and the promotion of successful female entrepreneurial role models should be implemented to enhance entrepreneurial confidence among female students. Thirdly, entrepreneurship educators should encourage students to embrace risk-taking by allowing them to experiment and learn from their own mistakes. This can be achieved by presenting case studies and examples of successful entrepreneurs who have taken risks, as well as offering practical exercises that involve decision-making under uncertainty. This will help to stimulate the RTP, which has been found to significantly influence PBC, EI, and EB. Fourthly, the positive relationship between PBC, EI, and EB suggests a need for policymakers to design targeted interventions that focus on enhancing PBC through practical training programmes and improved access to resources. Government business support agencies should engage in campaigns targeted at students in educational institutions to create awareness about available market opportunities and convey information about technical support, mentorship programmes, and types of funding available for startups that could help promote sustainable entrepreneurship. This will enhance the perception of capability for starting a business and stimulate EI and EB among the students. Lastly, the government should collaborate with media houses to promote entrepreneurship as a viable career option and cultivate an entrepreneurial culture in South Africa. This could involve developing television programmes that highlight the benefits of entrepreneurship and sustainable entrepreneurship, as well as producing radio interviews with entrepreneurs from diverse industries. Examples such as Making Moves and My Start-Up SA have demonstrated the potential of local media to inspire entrepreneurial action, and similar initiatives, including educational YouTube channels and entrepreneurship-focused podcasts, can further expand this impact across South Africa. Additionally, the media should be leveraged to disseminate information about various entrepreneurial support programmes that promote sustainable entrepreneurship offered by the government to assist aspiring business owners. Reality TV shows showcasing sustainable startups can provide real-world insights into the daily challenges faced by entrepreneurs, offering viewers a deeper understanding of entrepreneurship and the benefits of sustainable entrepreneurship, increasing their interest in an entrepreneurial career, and boosting their confidence in starting and managing a business.

This study contributes to the advancement of the TPB and entrepreneurship research by empirically validating the role of risk-taking propensity, gender, media exposure, and financial and non-financial support in shaping entrepreneurial intentions, perceived behavioural control, and entrepreneurial behaviour among students, thus extending TPB’s applicability in a developing country context.

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Like many research endeavours, this study was not without its limitations. The limitations of this study include the use of cross-sectional data, as it was conducted within a specified timeframe, which prevented the possibility of a longitudinal study. A longitudinal study would have helped to establish the cause and effect relationships between the variables that were tested in this study. While the study established the relationship between EI and EB, the respondents were not tracked over time to establish the causality from intention formation to engagement in EB. A longitudinal study would help in overcoming this limitation. The study did not explore the complexities involved in the process of translating EI into actual behaviour. Additionally, the findings may not be generalisable to all student populations, as cultural, socioeconomic, and institutional differences could influence the results. Therefore, future research should specifically address gaps such as testing different cultural contexts to see if social norms influence gender disparities in entrepreneurship, examining how socioeconomic status impacts entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour, and exploring the role of institutional support systems in fostering entrepreneurial activity across diverse settings. There is a need to also conduct similar studies in other countries, including South African universities and TVET colleges to validate these results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.H.M. and M.J.M.; methodology, N.H.M.; software, N.H.M.; validation, M.J.M.; formal analysis, N.H.M.; investigation, N.H.M.; data curation, N.H.M.; writing—original draft, N.H.M.; writing—review and editing, M.J.M.; visualisation, N.H.M. and M.J.M.; supervision, M.J.M. and E.M.R.; funding acquisition, N.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by M.J.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tshwane University of Technology (REC Ref No.: REC2022/06/021, approved on 8 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

All the respondents completed the informed consent to participate in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amiri, N.S.; Marimaei, M.R. Concept of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs’ traits and characteristics. Sch. J. Bus. Adm. 2012, 2, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, M.; Silva, J.D. The factors that influence the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. J. Entrep. Educ. 2021, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Promoting Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development: A Selection of Business Cases from the EMPRETEC Network. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaeed2017d6_en.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Rosário, A.T.; Ricardo, J.R.; Sandra, P.C. Sustainable entrepreneurship: A literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.; Suresh, M. Exploring the contribution of sustainable entrepreneurship towards sustainable development goals: A bibliometric analysis. Green Technol. Sustain. 2023, 1, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) Q2: 2024 Report. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2%202024.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Meyer, N.; Samsami, M.; Bowmaker-Falconer, A. Woman Entrepreneurship in South Africa: What Does the Future Hold? GEM SA 2023/2024 Special Report. Available online: https://www.stellenboschbusiness.ac.za/sites/default/files/media/documents/2024-08/GEM_Womens_Special_Report_Electronic_Single_compressed.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Kibler, E. Formation of entrepreneurial intentions in a regional context. Entrep. Reg. Dev. Int. J. 2013, 25, 293–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothibi, N.H.; Malebana, M.J.; Rankhumise, E.M. Munificent environment factors influencing entrepreneurial intention and behaviour: The moderating role of risk-taking propensity. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nergui, E. The translation of entrepreneurial intention into behavior. Econ. Stud. 2020, 70, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ebewo, P.E.; Nesamvuni, A.E. Entrepreneurial environment as an antecedent of university students’ entrepreneurship intentions. J. Entrep. Innov. 2020, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M.J. Relationship between entrepreneurial support, business information seminars and entrepreneurial intention. J. Entrep. Educ. 2021, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T.; Lin, C.L.; Xu, D. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in China: Integrating the perceived university support and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.V.; Doanh, D.C. The role of structural support in predicting entrepreneurial intention: Insights from Vietnam. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1783–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Perceived representation of entrepreneurship in the mass media and entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacq, S.; Ofstein, L.F.; Kickul, J.R.; Gundry, L.K. Perceived entrepreneurial munificence and entrepreneurial intentions: A social cognitive perspective. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 1, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, A.G.; Kalu, O.O.; Esi-Ubani, C.O.; Paul Chinedu Agu, P.C. Drivers of sustainable entrepreneurial intentions among university students: An integrated model from a developing world context. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Subramaniam, N.; Nair, V.K.; Shivdas, A.; Achuthan, K.; Nedungadi, P. Women entrepreneurship and sustainable development: Bibliometric analysis and emerging research trends. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I.; Saleem, I. Exploring entrepreneurial characteristics among university students: An evidence from India. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 13, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Ferreira, J.J.; Raposo, M.; Sanchez, J.; Hernandez–Sanchez, B. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: An international cross-border study. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou, E.A.E.E.; Hanafi, M.; Ali, I.E.O. Entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of individual factors. Am. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Tang, Z. The relationship of achievement motivation and risk-taking propensity to new venture performance: A test of the moderating effect of entrepreneurial munificence. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2007, 4, 450–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embi, N.A.C.; Jaiyeoba, H.B.; Yussof, S.A. The effects of students’ entrepreneurial characteristics on their propensity to become entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Educ. + Train. 2019, 61, 1020–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, J.A.; Antoncic, B.; Gantar, M.; Hisrich, R.D.; Marks, L.J. Risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurship: The role of power distance. J. Enterprising Cult. 2018, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudstaal, M.; Roof, R.; Van Praag, M. Risk, uncertainty, and entrepreneurship: Evidence from a lab-in-the-field experiment. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2897–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmullen, J.S.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twum, K.K.; Kwakwa, P.A.; Ofori, D.; Nkukpornu, A. The relationship between individual entrepreneurial orientation, network ties, and entrepreneurial intention of undergraduate students: Implications on entrepreneurial education. Entrep. Educ. 2021, 4, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, N.A.; Marmaya, N.H.; Wee, N.M.B.M.F.; Arham, A.F.; Sa’ari, J.R.; Hafiza harun, N.N. Causal inferences—Risk-taking propensity relationship towards entrepreneurial intention among millennials. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U. Relationship between individual characteristics and social entrepreneurial intention: Evidence from Bangladesh. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2021, 12, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K. The psychology of the successful entrepreneur. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 2016, 1, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasip, S.; Amirul, S.R.; Sondoh, S.L.; Tanakinjal, G.H. Psychological characteristics and entrepreneurial intention: A study among university students in North Borneo, Malaysia. Educ. + Train. 2017, 59, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Van gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothibi, N.H.; Malebana, M.J. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners in Mamelodi, South Africa. Acad. Entrep. J. 2019, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, R.; Rocha-junior, W.; Xavier, A. Determinant factors of entrepreneurial intention among university students in Brazil and Portugal. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 32, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonz’alez-Serrano, M.H.; Valantine, I.; Mati’c, R.; Milovanovi’c, I.; Sushko, R.; Calabuig, F. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions in European sports science students: Towards the development of future sports entrepreneurs. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 29, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Tabash, M.I.; Siow, M.L.; Ong, T.S.; Anagreh, S. Entrepreneurial intentions of Gen Z university students and entrepreneurial constraints in Bangladesh. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilomo, M.; Mwantimwa, K. Entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate students: The moderating role of entrepreneurial knowledge. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2023, 11, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M.J. Entrepreneurial intentions of South African rural university students: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2014, 6, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, W. Exploring the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention with the theory of planned behaviour on Tunisian university students. Int. J. Appl. Behav. Econ. 2023, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.H.M.; Malek, E.N. An application of theory of planned behavior in determining student entrepreneurship intention. J. Intelek 2021, 16, 208–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrink, K.M.; Ströhle, C. The entrepreneurial intention of top athletes—Does resilience lead the way? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 20, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Kousar, S.; Rehman, C.A. Role of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial intentions and behaviour: Theory of planned behaviour extension on engineering students in Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, P.; Ghadermarzi, H.; Karimi, H.; Norouzi, A. The Process of Adopting Entrepreneurial Behaviour: Evidence from Agriculture Students in Iran. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/riie20 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- Joensuu-Salo, S.; Viljamaa, A.; Varamaki, E. Do intentions ever die? The temporal stability of entrepreneurial intention and link to behavior. Educ. + Train. 2020, 62, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual–Opportunity Nexus; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.T.M.; Giang, N.H.; Hoa, N.T.X. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention of higher diploma students in Hanoi-Vietnam. Rev. Gestão Soc.E Ambient. 2024, 18, e05955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. Environmental munificence for entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurial alertness and commitment. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2008, 14, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, S.A.; Yakubu, M.S. Entrepreneurship education, environmental support and entrepreneurial intention mediating role of pro-activeness. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2020, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, S.; Panda, R.K. Exploring entrepreneurial orientation and intentions among technical university students: Role of contextual antecedents. Educ. + Train. 2019, 61, 718–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Small Business Development. Annual Report 2020/21 Financial Year. Available online: http://www.dsbd.gov.za//sites/default/files/2021-09/DSBD2020-21-annual-report.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Çera, G.; Çera, E.; Rozsa, Z.; Bilan, S. Entrepreneurial intention as a function of university atmosphere, macroeconomic environment and business support: A multi-group analysis. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 45, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M.J. Knowledge of entrepreneurial support and entrepreneurial intention in the rural provinces of South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2017, 34, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.; Urbano, D.; Coduras, A.; Ruiz-Navarro, J. Environmental conditions and entrepreneurial activity: A regional comparison in Spain. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2011, 18, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Song, Y.; Pan, B. How university entrepreneurship support affects college students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmaditya, B.S.; Wardoyo, C.; Wibowo, A.S.; Sahid, S. Does entrepreneurial ecosystem drive entrepreneurial intention and students’ business preparation? Lesson from Indonesia. J. Effic. Responsib. Educ. Sci. 2024, 17, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Sanchez, A.; Baixauli-Soler, S.; Carrasco-Hernandez, A.J. A missing link: The behavioral mediators between resources and entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of access to finance and incubation center. J. Asian Dev. Stud. 2024, 13, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, F.M. Financial inclusion in Africa: Does it promote entrepreneurship? J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2020, 12, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzomonda, O.; Fatoki, O. Entrepreneurial action as an antecedent to new venture creation among business students in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives, Johannesburg, South Africa, 3–5 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luc, P.T. The relationship between perceived access to finance and social entrepreneurship intentions among university students in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2018, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, G.R.; Soomro, B.A.; Channa, A.; Channa, S.A.; Khushk, G.M. Perceived access to finance and social entrepreneurship intentions among university students in Sindh, Pakistan. Palarch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Saoula, O.; Abid, M.F.; Ahmad, M.J.; Shamim, A. What drives entrepreneurial intentions? Interplay between entrepreneurial education, financial support, role models and attitude towards entrepreneurship. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2025, 19, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Malik, M.I. Towards nurturing the entrepreneurial intentions of neglected female business students of Pakistan through proactive personality, self-efficacy and university support factors. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Elnadi, M.; Gheith, M.H.; Farag, T.F. How does the perception of entrepreneurial ecosystem affect entrepreneurial intention among university students in Saudi Arabia? Int. J. Entrep. 2020, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, S.J.; Casteleiro, C.M.L.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Guerra, M.D. Entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurship in European countries. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambad, S.N.A.; Damit, D.H.D.A. Determinants of entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate students in Malaysia. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipeta, E.M.; Surujlal, J. Influence of attitude, risk taking propensity and proactive personality on social entrepreneurship intentions. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V.; Shahidi, S. Does the ability to make a new business need more risky choices during decisions? Evidence for the neurocognitive basis of entrepreneurship. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, W.I.; Moore, W.T. The influence of entrepreneurial risk assessment on venture launch or growth decisions. Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 26, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jiang, W. Risk-taking for entrepreneurial new entry: Risk-taking dimensions and contingencies. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 739–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Kollmann, T.; Krell, P.; Stöckmann, C. Understanding, differentiating, and measuring opportunity recognition and opportunity exploitation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsudin, S.F.F.B.; Al Mamun, A.; Nawi, N.B.C.; Nasir, N.A.B.M.; Zakaria, M.N.B. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention among the Malaysian University Students. J. Dev. Areas 2017, 51, 424–431. [Google Scholar]

- Tipu, S.A.A. Entrepreneurial risk taking: Themes from the literature and pointers for future research. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.S.; Abdulrab, M.; ALwaheeb, M.A.; Alshammari, N.G.M. Factors impacting entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia: Testing an integrated model of TPB and EO. Educ. + Train. 2020, 62, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Harm, J.A.; Biemans, K.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. Testing the relationship between personality characteristics, contextual factors and entrepreneurial intentions in a developing country. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Cain, K.W. Reassessing the link between risk aversion and entrepreneurial intention:the mediating role of the determinants of planned behavior. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 93–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, I.H.F. Gender differences in entrepreneurial attitude and intentions among university students. Int. Conf. Adv. Bus. Manag. Law 2018, 2, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Colla, E. Are there gender differences in entrepreneurial orientation and performance? Evidence from French franchisees. In Networks in International Business: Managing Cooperatives, Franchises and Alliances; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S.; Ionescu-Somers, A.; Coduras, A. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023/2024 Global Report: 25 Years and Growing. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=51377 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Malebana, M.J. Gender differences in entrepreneurial intention in the rural provinces of South Africa. J. Contemp. Manag. 2015, 12, 615–637. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, J.; Leroy, H.; Sels, L. Gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions: A TPB multi-group analysis at factor and indicator level. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palupi, D.; Santoso, B.H. An empirical study on the theory of planned behavior: The effect of gender on entrepreneurship intention. J. Econ. Bus. Account. Ventur. 2017, 20, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dubey, P.; Sahu, K.K. Examining the effects of demographic, social and environmental factors on entrepreneurial intention. Manag. Matters 2022, 19, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamet, A.R.; Hidayati, N.; Agustina, I. Analyzing gender differences of entrepreneurial intention among student in Islamic University Malang. Int. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2022, 5, 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, M.; Saleem, S.; Raoof, R.; Sultana, N. Impact of Media on Entrepreneurship Participation: A Cross-Country Panel Data. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343556141_Impact_of_Media_on_Entrepreneurship_Participation_A_Cross-Country_Panel_Data_Analysis (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Levie, J.; Hart, M.; Karim, M.S. Impact of Media on Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Available online: https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/18403/ (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychol. 2001, 3, 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D.; Stenholm, P. Attracting the entrepreneurial potential: A multilevel institutional approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 168, 120748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekiya, A.A.; Ibrahim, F. Entrepreneurship intention among students: The antecedent role of culture and entrepreneurship training. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2016, 14, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pillis, E.; Reardon, K.K. The influence of personality traits and persuasive messages on entrepreneurial intention: A cross-cultural comparison. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hafaïedh, C.; Ratinho, T. Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Effectuation: An Examination of Team Formation Processes. In Entrepreneurial Behaviour; McAdam, M., Cunningham, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Chapter 5; pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mcadam, M.; Cunningham, J.A. Entrepreneurial Behaviour: Individual, Contextual and Microfoundational Perspectives; Springer Nature: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, M.; Baei, F.; Hosseini-Amiri, S.H.; Moarefi, A.; Suifan, T.S.; Sweis, R. Proposing a model of manager’s strategic intelligence, organization development, and entrepreneurial behavior in organizations. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Klapper, R.; Ratten, V.; Fayolle, A. Emerging themes in entrepreneurial behaviours, identities and contexts. J. Entrep. Innov. 2018, 19, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshmaram, M.; Shiri, N.; Shinnar, R.S.; Savari, M. Environmental support and entrepreneurial behavior among Iranian farmers: The mediating roles of social and human capital. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 1064–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, B.; Iqbal, M.A. The impact of entrepreneurial skills, entrepreneurship education support programmes and environmental factors on entrepreneurial behaviour: A structural equation approach. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 18, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doung, C.D.; Ha, N.T.; Le, T.L.; Nguyen, T.L.P.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Pham, T.V. Moderating effects of COVID-19-related psychological distress on the cognitive process of entrepreneurship among higher education students in Vietnam. High. Educ. Ski. Work.-Based Learn. 2022, 12, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S. Modelling the significance of social support and entrepreneurial skills for determining entrepreneurial behaviour of individuals: A structural equation modelling approach. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 14, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E.; Kautonen, T.; Fink, M. Regional social legitimacy of entrepreneurship: Implications for entrepreneurial intention and start-up behaviour. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loan, L.T.; Cong, D.D.; Thang, H.N.; Nga, N.T.V.; Van, P.T.; Hoa, P.T. Entrepreneurial behaviour: The effects of the fear and anxiety of COVID-19 and business opportunity recognition. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.M.A.T.; Mamun, A.A.; Ahmad, G.B.; Ibrahim, M.D. Predicting entrepreneurial intentions and pre-start-up behaviour among Asnaf Millennials. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwiya, B.M.K.; Wang, Y.; Kaulungombe, B.; Kayekesi, M. Exploring entrepreneurial intention’s mediating role in the relationship between self-efficacy and nascent behaviour: Evidence from Zambia, Africa. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.N.; Vu, T.N.; Pham, H.T.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Doung, C.D. Closing the entrepreneurial attitude-intention-behavior gap: The direct and moderating role of entrepreneurship education. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2024, 17, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A.; Restrepo, L.A.M. Entrepreneurial intentions among engineering students: Applying a theory of planned behavior perspective. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2020, 28, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M.J. Entrepreneurial Intent of Final-Year Commerce Students in the Rural Provinces of South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsang, L. Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation: An Assessment of Students. Master’s Thesis, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Murad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ashraf, S.F.; Dogbe, C.S.K. Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 13, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).