1. Introduction

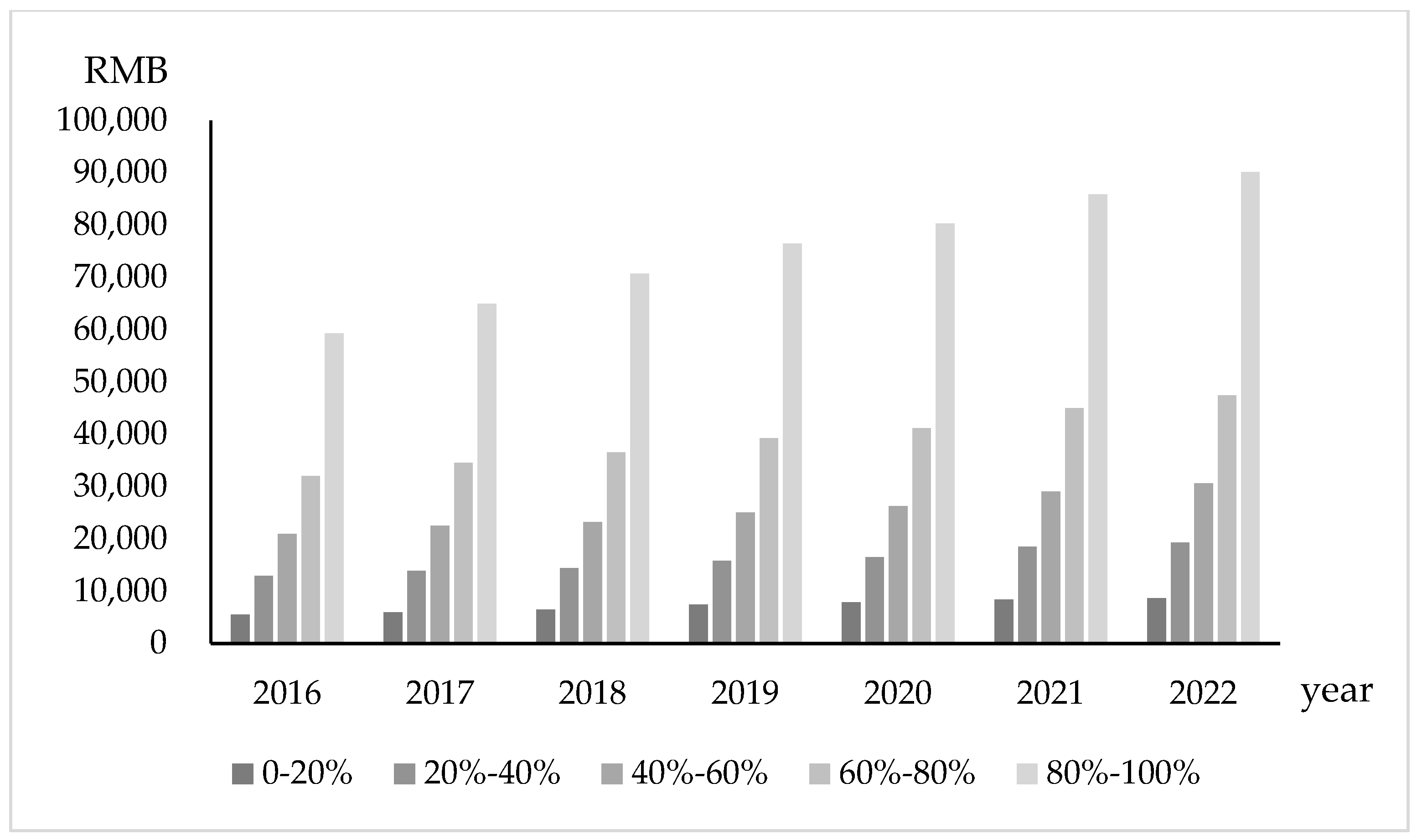

Income inequity remains a persistent and critical issue in economic discourse. Recent economic development and technological advancements have spurred household income growth. However, this growth has also contributed to changing income inequity. As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, although the Gini coefficient and the urban–rural income ratio have gradually stabilized, the disposable income across five distinct residential groups from 2016 to 2022 reveals persistent income disparities, despite overall increases in disposable income. These trends indicate that income inequity is an evolving phenomenon.

Education plays a crucial role in determining income and income inequity. The expansion of education has been supported by policies such as the popularization of compulsory education and the expansion of college entrance examination enrollment in China. However, as the direct manifestation of education’s return, the question of whether expanding education leads to a reduction in income inequity remains unresolved [

1,

2,

3]. The relationship between education and income inequity, which this paper terms educational income inequity (EII), warrants further exploration. As the digital economy (DE) continues to expand, the relationship between education and income inequity is likely to become more complex, presenting new challenges and changes. This paper aims to explore this evolving dynamic.

Inequity is often measured within distinct groups, making the definition of these groups essential. Research on income inequity, including the urban–rural income gap, frequently uses hukou as a grouping variable. However, despite the growing importance of education, there is limited discussion on the relationship with income inequity. This paper defines this relationship as EII, which refers to income disparities resulting from differences in educational attainment, similar to urban–rural income inequity. Specifically, EII captures income disparities among residents caused by educational divergence within cities. This framework allows for a quantifiable measure of how education impacts income inequity. To fully explore this impact, both individual educational attainment and parental education levels are considered. Parental education plays a significant role in children’s educational outcomes, and as such, individual education cannot be fully understood without considering the family background. Therefore, comparing individual education and family education provides additional insights into the impact of the DE on EII.

The DE has become a crucial driver of high-quality economic growth in China [

4,

5]. In recent years, the DE has gained significant attention, marked by milestones such as the full integration of the industrial internet across major sectors by 2023. Additionally, 5G applications directly contributed CNY 1.86 trillion to total economic output (Data from the reports in

http://www.gov.cn/, accessed on 3 November 2024). As these data demonstrate, the DE has significantly influenced household incomes, making the relationship between the DE and income inequity an important topic of inquiry [

6,

7]. While the DE offers numerous benefits, digital literacy is essential for individuals to fully leverage its potential [

8]. However, the digital divide remains a significant barrier, preventing some individuals from benefiting from DE. Digital skills are strongly linked to educational attainment, which creates disparities in how individuals benefit from the DE [

9]. Therefore, education, income inequity, and the DE are deeply intertwined. However, limited studies have focused on the impact of the DE on EII.

Given the limited literature directly addressing the impact of the DE on EII, existing studies have only occasionally noted that education or skill levels may mediate the effects of the DE on income inequity. Furthermore, the relationship between the DE and income inequity remains inconclusive, largely due to complex factors such as the Matthew Effect, which is closely linked to digital skills related to education [

10,

11]. Although the body of research on the DE and income inequity is expanding, much of it focuses on disparities driven by urban–rural divides or gender differences [

12,

13,

14]. Building on these studies, there remains a need for a more systematic investigation into how education influences the heterogeneity of the DE’s effects on income inequity. In light of these discussions, this paper introduces education as a key grouping factor for income inequity and focuses on the DE’s effect on EII. In the context of the DE’s rapid expansion, understanding its impact on education-driven income inequity is vital for informing policy decisions, particularly in promoting broader access to education as a means to achieve the goal of common prosperity.

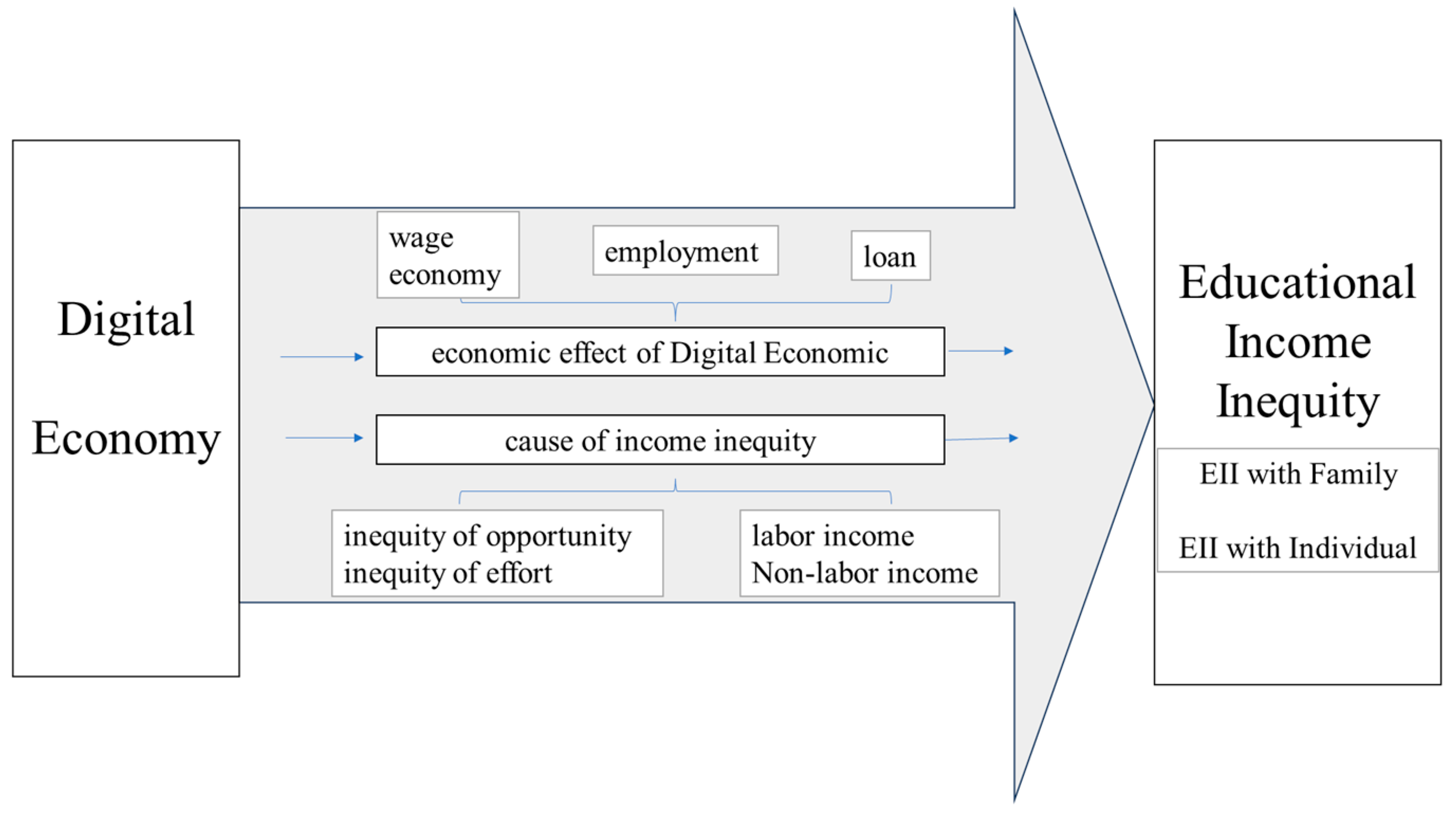

This paper examines how the DE within macro-regions affects micro-level EII among residents in cities in China, using a two-way fixed effects model with panel data from China. The study contributes to the literature introduces in several ways. First, it presents the relationship between education and income inequity, termed EII, through the Theil index, with education as the key grouping variable. This method builds on the approach used to measure urban–rural income inequity and establishes a foundational framework for further analysis. Second, the study incorporates both individual and household characteristics in measuring EII. This approach captures the dual influences of public education systems and family background, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment. By comparing the impact of the DE on both forms of EII, the analysis indirectly reveals the transmission channels through which the DE operates. Lastly, the study identifies the underlying causes of inequity as significant mechanisms through which the DE affects EII. By decomposing EII into income and inequity components, this study introduces a novel analytical perspective that departs from existing literature. Furthermore, empirical evidence is provided to show that the DE influences EII by generating effects on employment, income, and capital flows.

The structure of this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant studies on the DE and EII, proposing corresponding hypotheses.

Section 3 focuses on model construction.

Section 4 presents the results and interpretations.

Section 5 offers analyses and results of mechanisms.

Section 6 discusses heterogeneity analysis. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes discussion and a brief conclusion.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Model Design

The objective of this study is to analyze the impact and mechanisms through which the DE in cities influences EII among residents. Industrial structure, the number of enterprises, and the employment situation are closely interconnected [

23], while financial pressure directly affects the level of infrastructure development. Population density is strongly associated with the demand for the DE, educational attainment, and competition in the labor market. Naturally, a wide range of factors are relevant to both the DE and EII. However, based on the foundation established by existing studies [

13,

23] and in line with the objectives of this paper, particular attention is given to these specific variables. Panel data at the city level are utilized to construct a two-way fixed effects model (Equation (1)).

In this model, denotes EII in cities, which includes education factors both family and individual; denotes the DE in cities, measured as a comprehensive index; i and t denote city and year, respectively; represents the set of control variables, which include population density, the proportion of employees in the secondary industry, the number of industrial enterprises above the designated size in the city, and financial pressure. The terms denote the city and year fixed effects; denotes random error terms, clustered at the city level; and the coefficients are to be estimated. It is important to note that, in order to mitigate potential endogeneity issues arising from reverse causality, the DE is introduced into the model with a one-period lag.

3.2. Calculation of EII and the DE

To calculate the income inequity attributed to education, this paper uses the Theil index. Groups are based on the education levels of both family and individual. This approach allows for the decomposition of EII into “opportunity” and “effort” components. In addition, educational attainment in family is typically measured using the educational level of the household head (

huzhu) [

3]. In the Chinese context, this role is most commonly held by the father. The father’s education level serves as a proxy for family education, while the individual’s own education level measures individual education.

Family education is categorized into four groups as follows: illiterate, below or including compulsory education, high school education, and higher education. Individual education is classified into three groups as follows: below or including compulsory education, high school education, and higher education. There is no illiterate category for individual education.

In this model, denotes different groups, classified according to the education levels of the family and individual; denote the proportion and number of personnel per group; denote members and groups of the set ; is the mean income within each group; reflects inter-group inequity, representing the inequity of opportunity; and captures the inequity within each group, signifying the inequity of effort.

Given the diverse sources of income, total income is used in EII for both family and individual. Labor EII and non-labor EII are used to analyze the causes of income in the mechanism. Both family and individual education are calculated to explore the influence of education on income inequity.

The DE is a multifaceted variable. It includes infrastructure components such as internet access and evaluates its role in fostering economic growth through financial services and products. Accurately assessing regional DE levels is essential for understanding its impact on EII. This study constructs an indicator system (

Table 1) based on existing literature. It draws on the framework developed by Zhao et al. [

39], which constructs an indicator system using PAC for DE, focusing on internet infrastructure, information development, and the level of inclusive financial services. Principal component analysis is then used to evaluate DE levels across cities.

3.3. Data Source and Descriptive Statistics

The income data used in this study are sourced from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) for the years 2012, 2013, and 2015. The CGSS is the earliest and most comprehensive continuous academic survey project in China. It collects data across multiple societal levels, including community, family, and individual. Using CGSS data allows for a more accurate measurement of EII in this study. However, due to limitations in city code availability, only data from 2012, 2013, and 2015 are used. Additional data are obtained from the City Statistical Yearbook and the Center for Digital Finance at Peking University.

Descriptive statistics for the main variables are presented in

Table 2. The difference in EII between family and individual is relatively small. However, significant differences are observed between labor and non-labor income, both between family and individual. And the non-labor EII in relation to family is bigger than that in relation to just individuals. Additionally, there is notable heterogeneity in the levels of DE. The other variables in the model serve as control variables.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Discussion

This paper innovatively incorporates education from both household and individual perspectives into the analysis of EII. It offers a more comprehensive understanding of income inequity resulting from education. It directly examines the impact of the DE on EII by analyzing the interplay between DE, education, and income inequity. Existing studies have primarily focused on two approaches. For example, the impact of the DE and (Non-)Cognitive Ability on labor income is analyzed using interaction models [

26], with findings indicating that the DE has a significantly positive effect on the labor income of individuals with higher cognitive ability. Additionally, the effect of the DE on income inequity varies across groups with different education levels [

9,

20]. Although these studies do not directly address the relationship between the DE and EII, they provide empirical evidence that the effect of the DE on income inequity is conditional on education. This indirectly but crucially supports the findings of the present study.

The development of the DE has significant economic effects, especially on EII. However, the direction of this effect—whether positive or negative—remains inconclusive in the literature [

10,

11,

20,

53]. This paper examines the DE’s empirical effects in cities, emphasizing its role in promoting employment, increasing income, raising tax revenues, and stimulating loans, all of which influence EII. To further explain the DE’s impact on EII, the paper explores the following two key aspects: the types of income and the sources of inequity. This approach offers a novel perspective on studying the DE’s effect on income inequity, providing a more direct explanation of its impact on EII.

In heterogeneity analysis, the effect of the DE on EII is more pronounced in cities with stronger economic foundations, better public services, and more advanced telecommunications infrastructure. This is primarily because these cities exhibit higher DE, and the educational attainment of their residents is likely to be higher, making the impact more pronounced. This finding is supported by existing research [

17,

27].

In summary, the hypotheses proposed in this paper have been confirmed. This paper not only integrates education into the study of income inequity but also provides direct insights into the DE’s effect on EII. It analyzes the educational impact from both family and individual perspectives, contributing to existing literature on the influence of household background on income inequity.

However, the DE may also affect EII through channels, such as changing production methods and increasing technological progress rates. Due to data limitations, these issues require further exploration. In the future, we plan to explore longer-term data to further investigate the long-term effects of the DE on EII within the proposed research framework.

The findings of this study also hold significant practical implications. As the DE continues to flourish and the overall educational quality improves, addressing income inequity and advancing the goal of common prosperity have become key economic development objectives. While non-labor EII remains relatively high, the development of the DE does not appear to have a significant effect on this form of inequity. Thus, for individuals, enhancing digital skills and acquiring the necessary vocational competencies to keep pace with techno-logical advancements represent more effective strategies. The stronger impact of the DE on effort-based inequity, as compared to environmental inequity, further supports this view. For developing countries, this study provides theoretical evidence that leveraging the trends of DE growth can help reduce EII and improve overall welfare. For policymakers, in addition to continuing efforts to promote universal education, enhancing urban infrastructure and addressing regional development disparities are crucial for reducing income gap. For individuals, investing in digital skills training and acquiring the vocational skills required to thrive in an evolving job market is a core decision to avoid economic obsolescence.

7.2. Conclusions

Using panel data from cities in China, this paper finds that the DE significantly reduces EII from both individual and family perspectives. The effect remains robust even after addressing endogeneity with IVs. The DE exerts a positive economic impact by improving employment, wages, income, tax revenue, and promoting loans. These factors all contribute to reducing EII. The DE primarily affects labor income, rather than non-labor income, in reducing EII. It also significantly decreases both inequity of opportunity and effort, which are key mechanisms influencing EII. Notably, the DE’s impact on individual inequity of effort and opportunity shows little variation. However, its effect on inequity of effort in families is stronger than on inequity of opportunity. Further analysis reveals that in cities with stronger economic foundations, higher levels of public services, and greater telecommunications infrastructure, the DE’s impact on EII is more pronounced.