Learning Along the GreenWay: An Experiential, Transdisciplinary Outdoor Classroom for Planetary Health Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

- ▪

- Content—healthy built environments; sustainability; resilience

- ▪

- Process—transdisciplinarity

- ▪

- Organisational structures—One Health and the Planetary Health Education Framework.

2.1. What Are the Foundational Pillars upon Which Our Educational Philosophy and Practices Are Based?

2.1.1. Content—What Are the Core Theoretical Content Areas of Our Programmes?

- Healthy Built Environments (HBEs)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Resilience

2.1.2. Process

- Transdisciplinarity

2.1.3. Organising Structures

- One Health

- Planetary Health Educational Framework

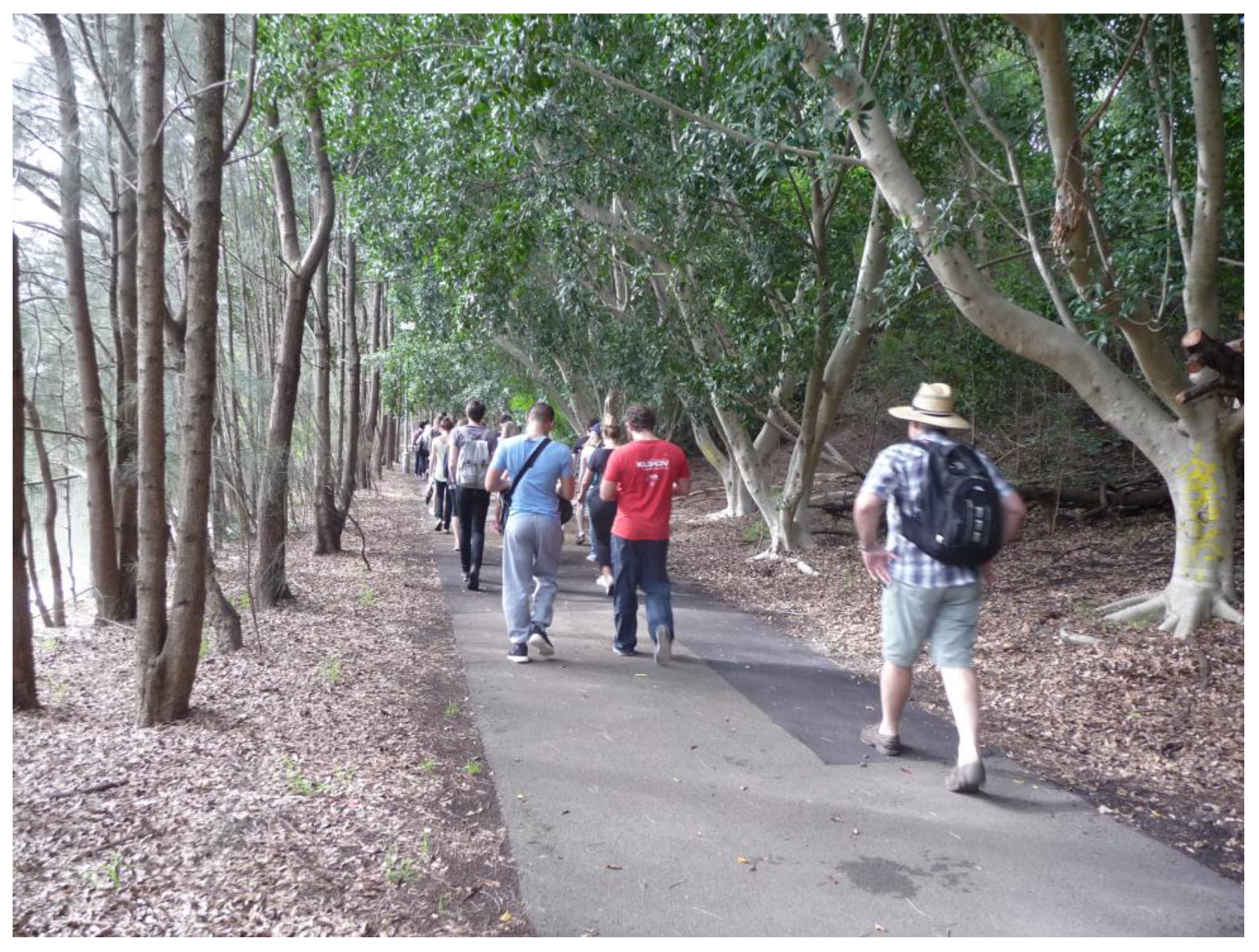

3. The GreenWay Place for Education

3.1. What Is the GreenWay and What Are Its Features?

3.2. Historical Evolution of the GreenWay

- Protection and extension of a local urban environment to support open space and community health outcomes

- A range of education activities around valuing local ecology and broader sustainability imperatives

- Development of physical, political and organisational processes to overcome barriers and achieve a more integrated approach to development and management of the GreenWay as one continuous, multi-purpose urban green corridor

- Creation of an integrated GreenWay Place Management programme [38] with five ongoing and fundamental elements:

- ▪

- Place making initiatives

- ▪

- Building extensive infrastructure for connected active travel

- ▪

- Bushcare sites and activities

- ▪

- Educational programmes using the GreenWay as an outdoor classroom

- ▪

- A broad range of arts and cultural activities.

4. The GreenWay as an Outdoor Classroom

4.1. The Schools Educational Program: History, Development and Overview

- ▪

- ‘Where in the world’—a range of activities to help students geographically situate the GreenWay and to identify key features such as the Cooks River, Hawthorne canal and Iron Cove; learning activities embrace mapping protocols (legends and standard map notations), the concept of a mud map, which students draw; and detailed instructions on the use of Google Earth to find the GreenWay [39] (pp. 50–53).

- ▪

- ‘The drain is just for rain’—this set of activities focuses on a range of rubbish types that emanate from households just like the students (this is immediately relatable to children’s experience and knowledge)—dirt and leaves swept into the gutter; animal waste left on the grass verge; oils and detergents from on-road or driveway car-washing; household garbage such as plastic bags that are easily blown away [39] (pp. 83–85).

- ▪

- ‘Rubbish’—this activity focuses on the main types of rubbish collected from the Hawthorne canal (which the children explore during their GreenWay walk). Differences between natural and manufactured waste are presented. Rubbish capture via a pollutant trap in the Hawthorne canal (Figure 10) emphasises the enormity of the problem in their own backyard. Children are encouraged to take actions to reduce rubbish, make sure they clean up after their dog, and join in community clean-ups [39] (pp. 86–98).

- ▪

- ‘Art on the GreenWay’—children are introduced to some of the artworks along the GreenWay. Importantly, this includes a large mural and mosaic installation which several local schools played a major part in creating with community artists and activists (Figure 12). This artwork made a previously dark and uninviting underpass safe, light and engaging for walkers and cyclists [39] (pp. 116–127).

- ▪

- ‘Let’s go’—in this module the notion of a transport corridor is introduced. This is a key feature of the GreenWay and likely to be used by many of the children. Their task is to design a light rail stop that is safe and easy to use with features such as toilets, seating, clear signs, and a place to buy tickets [39] (pp. 181–183).

- ▪

- Collecting six objects from a section of parkland on the GreenWay and storing them in an egg box: (i) a natural object (ii) an artificial object (iii) a black object (iv) a prickly object (v) a shiny object (vi) a smooth object.

- ▪

- ▪

- ‘Bug’ hunting involving digging in topsoil/mulch for bugs and identifying the type of bug with a magnifying glass (Figure 21).

- ▪

- Making bracelets using Lomandra leaves (particularly a favourite with young girls).

Evaluating the School’s Educational Program

- ▪

- It was fabulous; it gave us the building blocks to link our teaching programme and tailor it to our needs.

- ▪

- Very engaging and informative. I learnt heaps myself.

- ▪

- Students benefitted from making discoveries in their own backyard.

- ▪

- Amazing fun and interesting facts; reinforced our history topic of inquiry.

- ▪

- Great initiative in eco-literacy; it should be compulsory for all local schools.

- ▪

- Because nature is a part of life.

- ▪

- Because there are living things like us.

- ▪

- Nice to look at [and] a home to animals.

- ▪

- A reliable track for active people.

- ▪

- Has a lot of ‘environment’ which helps us breathe.

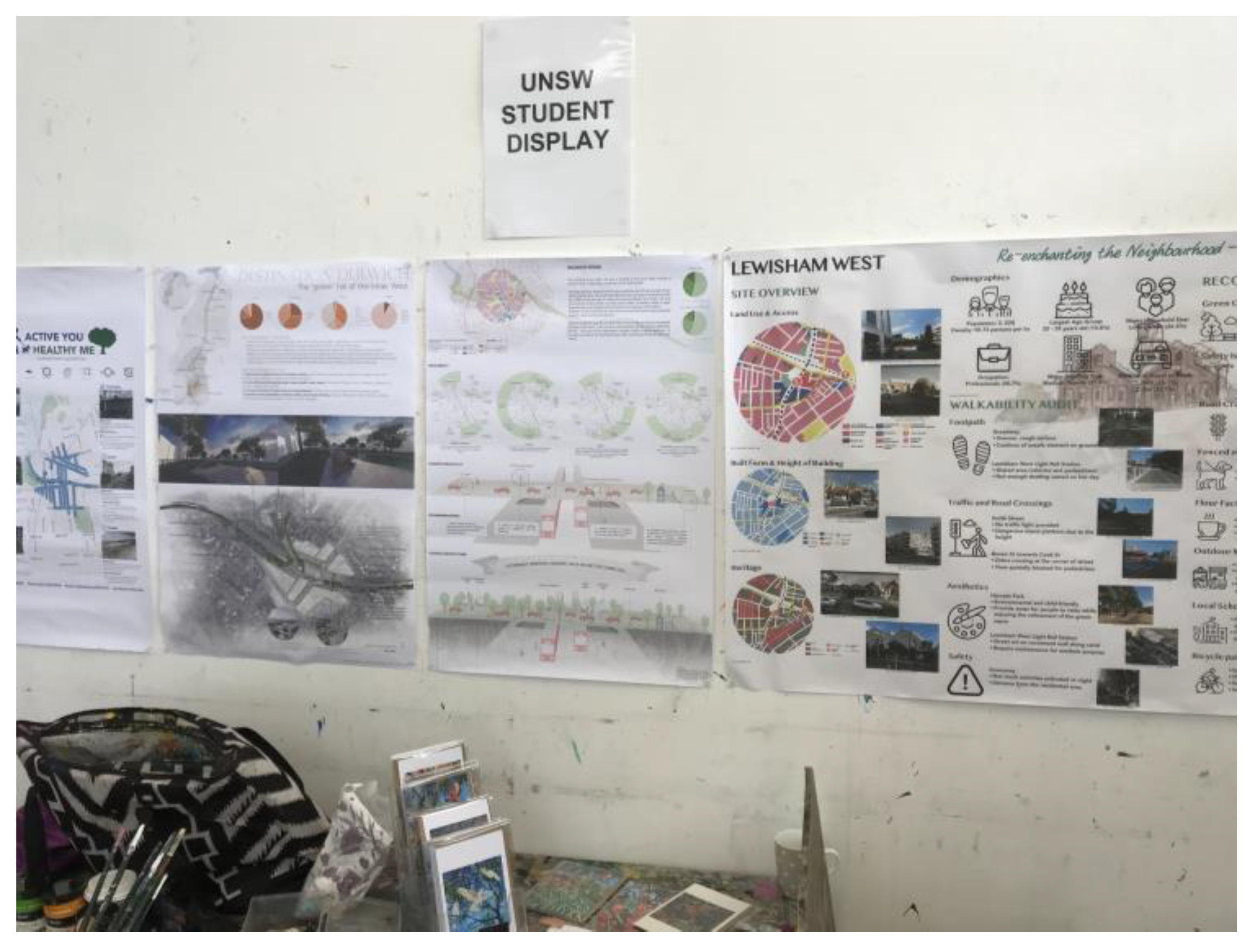

4.2. The Tertiary Educational Programme: History, Development and Overview

- The University of New South Wales (UNSW)

- ▪ The essential cross-disciplinary nature of the task of planning to create environments that support healthy behaviours especially those that reduce the risk of chronic disease.

- ▪ Transdisciplinary ways of working and interacting to appreciate the different languages and value systems used by both health and built environment policy makers and practitioners.

- ▪ Specific tasks, such as health and wellbeing audits.

- University of Technology Sydney (UTS)

- ▪ The planners are assigned a light rail station within the GreenWay and tasked with developing a master plan for the surrounding precinct.

- ▪ In small multidisciplinary groups, the landscape class examines the GreenWay as a green infrastructure corridor opportunity and makes recommendations for enhancement.

- ▪ The Winter Design School cohort develops affordable treatments aimed at improving the design quality and pedestrian amenity at the light rail stops and along the GreenWay, both during the day and, most importantly, at night.

- Define the Site—getting to know the site by documenting physical boundaries (such as waterways, walking paths, and roads) and environmental quality.

- Understand the Site—land-use study and detailed observations of the quality and character. For example, residential density, types of housing, extent of commercial development, and other significant built, natural or social features present within the neighbourhood. As well, the general demographic characteristics of the population are researched and described.

- Walkability—an audit of walkability is conducted using prescribed professional tools—students focus on key concepts of sustainability, connectivity, health, inclusivity and pedestrian safety.

- Recommendations—a set of appropriate recommendations to improve walkability and pedestrian safety and comfort around the light rail stop are devised.

- i

- What improvements are needed to activate the site and enhance its ‘look and feel’ for all sections of the community?

- ii

- How might the site relate better to surrounding streets and associated land uses?

- iii

- What conflicts (e.g., between cyclists, dog walkers and commuter pedestrians; cars and cyclists) are evident, and how might they be managed and reduced?

- iv

- Are there particular ways to enhance accessibility for different community groups?

- v

- What about safety for light rail customers and GreenWay users at different times of the day and evening, weekdays and weekends?

- vi

- What is the future scenario for 20 years hence?

- vii

- Is there a need for interdisciplinary action across relevant local, state, community and development organisations?

- viii

- How might these groups work effectively together to deliver value for money and measurable community benefits across your site?

- ix

- What constraints might impede progress?

- x

- Consider current council policies, development applications and the likely future impact of resultant development.

Evaluating the Tertiary Educational Programs

- UNSW

- UTS

5. Discussion: The GreenWay—Contributing to the Educational Framework for Planetary Health and One Health

5.1. What Does Our Practice Offer the Planetary Health Education Framework and One Health?

- Anthropocene and Health

- Movement building and systems change

- Systems thinking and complexity

- Equity and social justice

- Interconnection with nature

5.2. Logistical Educational Hurdles

6. Conclusions and Recommendations for Educators

Recommendations for Caring and Committed Environmental Educators

- Articulate who you are as an environmental educator—communicate this to other educators and environmental advocates to demonstrate commitment.

- Lobby your close colleagues to support and advocate for contemporary, transdisciplinary and authentic environmental education programmes.

- Find a suitable and readily accessible local outdoor classroom—a green place, ideally with community involvement, environmental challenges and complex governance issues.

- Seek out a broad base of support beyond your school or university—if possible, find funds, but if not available, seek in-kind assistance from local agencies and community members and emphasise the urgency of arresting climate change anxiety in the young to empower, skill and inspire.

- Work with like-minded school and university educators in determining the level(s) of your programme(s) and other potential related activities such as active transport to school.

- Put local and authentic experiences at the heart of the educational curriculum—this is critical to inspire hope, care and commitment to the environment.

- Establish a respectful relationship with local Indigenous leaders and work with them so that they can be central to the programme(s).

- Use theoretical frameworks such as One Health, the Planetary Health Education Framework and the UN’s Sustainability Development Goals to justify and underpin the foundations of the educational programme(s).

- Establish committed and ongoing relationships with practitioners to engage them with the delivery of the classroom activities and feedback on student projects.

- Use learning outcomes to showcase to external stakeholders, including communities, the practical relevance and innovation of student ideas to address human and planetary health challenges.

- Prioritise professional development for educators, especially primary school teachers, about using outdoor classroom environments to teach core curriculum subjects in a transdisciplinary way.

- Continue with perseverance—this is long-term and critical education for the next generation—do not give up despite different challenges, political shifts, and funding ebbs and flows.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faerron Guzmán, C.A.; Aguirre, A.; Astle, B.; Barros, E.; Bayles, B.; Chimbari, M.; El-Abbadig, N.; Everth, J.; Hacketti, F.; Howard, C.; et al. A Framework to Guide Planetary Health Education. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e253–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization). One Health Website. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Tomassi, A.; Caforio, A.; Romano, E.; Lamponi, E.; Pollini, A. The development of a Competence Framework for Environmental Education complying with the European Qualifications Framework and the European Green Deal. J. Environ. Educ. 2024, 55, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWC (Inner West Council). GreenWay. 2025. Available online: https://www.greenway.org.au/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A global survey. Lancet 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, J.L.; Thompson, S.M. Planning Australia’s Healthy Built Environments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Healthy Cities: Effective Approach to a Rapidly Changing World. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240004825 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Barton, H.; Thompson, S.; Burgess, S.; Grant, M. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a Sustainable and Healthy Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H.; Tsourou, C. Healthy Urban Planning: A WHO Guide to Planning for People; Spon Press on Behalf of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Corburn, J. Toward the Healthy City: People, Places, and the Politics of Urban Planning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, H.; Frank, L.; Frank, L.D.; Jackson, R.J. Urban Sprawl and Public Health: Designing, Planning, and Building for Healthy Communities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Geneva, United Nations General Assembly Document A/42/427; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Planetary Health Alliance. What Is Planetary Health? 2025. Available online: https://planetaryhealthalliance.org/what-is-planetary-health/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Sustainability Development Goals. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/sustainable-development-goals#:~:text=The%20Sustainable%20Development%20Goals%20(SDGs,no%20one%20is%20left%20behind (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Pineo, H. Healthy Urbanism: Designing and Planning Equitable, Sustainable and Inclusive Places; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagle, E. The Four Cornerstones of Resilience Engineering. In Resilience Engineering Perspectives; Hollnagel, E., Nemeth, C.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- City of Sydney. Resilient Sydney: A Strategy for City Resilience; City of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://file:///C:/Users/z9100170/Downloads/Resilient%20Sydney%20A%20strategy%20for%20city%20resilience%202018%20(1).pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Willoughby City Council. Resilient Willoughby Strategy and Action Plan 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.willoughby.nsw.gov.au/Community/Community-health-and-safety/Resilient-Willoughby (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Lawrence, R.J. Co-Benefits of Transdisciplinary Planning for Healthy Cities. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.J. Creating Built Environments: Bridging Knowledge and Practice Divides; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bammer, G. Integration and Implementation Sciences: Building a new specialization. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhauser, L.; Richardson, D.; Mackenzie, S.; Minkler, M. Advancing Transdisciplinary and Translational Research Practice: Issues and models of doctoral education in public health. J. Res. Pract. 2007, 3, M19. [Google Scholar]

- Youngblood, D. Multidisciplinarity, Interdisciplinarity, and Bridging Disciplines: A matter of process. J. Res. Pract. 2007, 3, M18. [Google Scholar]

- Botchwey, N.D.; Hobson, S.E.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Mumford, K.G.; Contant, C.K.; McMillan, T.E.; Jackson, R.J.; Lopez, R.; Winkle, C. A Model Curriculum for a Course on the Built Environment and Public Health Training for an Interdisciplinary Workforce. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36 (Suppl. S2), S63–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.M.; Capon, A.G. Designing a Healthy and Sustainable Future: A Vision for Interdisciplinary Education, Research and Leadership. paper presented at Connected 2010. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Design Education, Sydney, Australia, 28 June–1 July 2010; The University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2010. Available online: https://www.be.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/upload/pdf/cf/hbep/publications/attachments/ConnectED_Conference_Paper_2010.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- WHO (World Health Organization). Leaders Call for Scale-Up in Implementing One Health Approach. Media Release. Geneva. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-02-2024-leaders-call-for-scale-up-in-implementing-one-health-approach (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Lerner, H.; Berg, C. A Comparison of Three Holistic Approaches to Health: One Health, EcoHealth, and Planetary Health. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; UNEP; WHO; WOAH. One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–2026). In Working Together for the Health of Humans, Animals, Plants and the Environment; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; United Nations Environment Programme; World Organization for Animal Health. A Guide to Implementing the One Health Joint Plan of Action at National Level; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240082069 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Redvers, N.; Faerron Guzmán, C.A.; Parkes, M.W. Towards an educational praxis for planetary health: A call for transformative, inclusive, and integrative approaches for learning and relearning in the Anthropocene. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e77–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faerron Guzmán, C.A.; Potter, T. (Eds.) The Planetary Health Education Framework; Planetary Health Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.planetaryhealthalliance.org/education-framework (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabolch, M. Hawthorne Canal: The History of Long Cove Creek; Ashfield & District Historical Society/Inner West Environment Group: Sydney, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- EG Property. The Flour Mill of Summer Hill: New Heart, Old Soul. 2025. Available online: https://eg.com.au/case-studies/developments/the-flour-mill-of-summer-hill (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Hassell. Flour Mill of Summer Hill. 2025. Available online: https://www.hassellstudio.com/project/summer-hill-flour-mill (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Greater Sydney Commission. Our Greater Sydney 2056—Eastern City District Plan: Connecting Communities (Updated); Greater Sydney Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2018. Available online: https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-04/eastern-city-district-plan.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- IWC (Inner West Council). GreenWay Masterplan. 2025. Available online: https://www.innerwest.nsw.gov.au/live/environment-and-sustainability/in-your-neighbourhood/bushland-parks-and-verges/greenway/greenway-masterplan (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Rossi, J.; Ashfield Council. Greenway Primary Schools Sustainability Program: Teachers Workbook. 2012. Available online: https://observatoryhilleec.schools.nsw.gov.au/primary-programs/s3-humans-shape-places-greenway.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- NSW Department of Education. Human Society and its Environment (HSIE) in Kindergarten to Year 10. 2025. Available online: https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/learning-areas/hsie (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- TfNSW (Transport for New South Wales). Get NSW Active. 2024. Available online: https://www.transport.nsw.gov.au/projects/programs/get-nsw-active (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Australian Association of Environmental Education. 2025. Available online: https://www.aaee.org.au/get-involved/your-chapter-or-branch/new-south-wales/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- NSW Department of Education. Environmental Education for Schools. 2025. Available online: https://education.nsw.gov.au/policy-library/policies/pd-2002-0049# (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Observatory Hill Environmental Education Centre. S3 Humans Shape Places—GreenWay. 2025. Available online: https://observatoryhilleec.schools.nsw.gov.au/primary-programs/s3-humans-shape-places-greenway.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- NSW Government Environment and Heritage. NSW Environmental Trust. 2025. Available online: https://www2.environment.nsw.gov.au/funding-and-support/nsw-environmental-trust (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- WHO (World Health Organization). Creating Healthy Cities. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/creating-healthy-cities (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Thompson, S.M.; Kent, J.K.; Lyons, C. Building Partnerships for Healthy Environments: Research, leadership and education. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 25, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, K.H.; Waggett, C.E.; Berenbaum, P.; Bayles, B.R.; Carlson, G.L.; English, R.; Faerron Guzmán, C.A.; Gartin, M.L.; Grant, L.; Henshaw, T.L.; et al. Planetary health learning objectives: Foundational knowledge for global health education in an era of climate change. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e706–e713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais Rodrigues, C.; Papageorgiou, E.; McLean, M. Development of a suite of short planetary health learning resources by students for students as future health professionals. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1439392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.J.; Ardoin, N.M.; Eames, C.; Monroe, M.C. Agency in the Anthropocene: Education for planetary health. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e117–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (AIDR) Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience, World Vision, Oaktree, Unicef Australia, Plan International, Save the Children, Australian Red Cross. National Survey of Children and Young People on Climate Change and Disaster Risk. 2020. Available online: https://www.aidr.org.au/media/7946/ourworldoursay-youth-survey-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- King, C.; Albanese Government Delivering 25,000 More Homes Across New South Wales. Media Release. 2025. Available online: https://minister.infrastructure.gov.au/c-king/media-release/albanese-government-delivering-25000-more-homes-across-new-south-wales (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- IWC (Inner West Council). Gadigal Wangal Wayfinding Project. 2021. Available online: https://www.innerwest.nsw.gov.au/live/living-arts/public-art-projects/gadigal-wangal-landscape-eoi (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Redvers, N.; Celidwen, Y.; Schultz, C.; Horn, O.; Githaiga, C.; Vera, M.; Perdrisat, M.; Plume, L.M.; Kobei, D.; Cunningham Kain, M.; et al. The determinants of planetary health: An Indigenous consensus perspective. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e156–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commonwealth of Australia. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2024–2030. 2025. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australias-strategy-for-nature-2024-2030.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, S.M.; Chapman, N. Learning Along the GreenWay: An Experiential, Transdisciplinary Outdoor Classroom for Planetary Health Education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094143

Thompson SM, Chapman N. Learning Along the GreenWay: An Experiential, Transdisciplinary Outdoor Classroom for Planetary Health Education. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094143

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Susan M., and Nick Chapman. 2025. "Learning Along the GreenWay: An Experiential, Transdisciplinary Outdoor Classroom for Planetary Health Education" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094143

APA StyleThompson, S. M., & Chapman, N. (2025). Learning Along the GreenWay: An Experiential, Transdisciplinary Outdoor Classroom for Planetary Health Education. Sustainability, 17(9), 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094143