Signs of Children’s Presence in Two Types of Landscape: Residential and Park: Research on Adults’ Sense of Safety and Preference: Premises for Designing Sustainable Urban Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. What Might Trigger Fear in a Given Space?

1.2. Sense of Safety Among Women and Men

1.3. The Aesthetics of Children and Adults

2. Materials and Methods

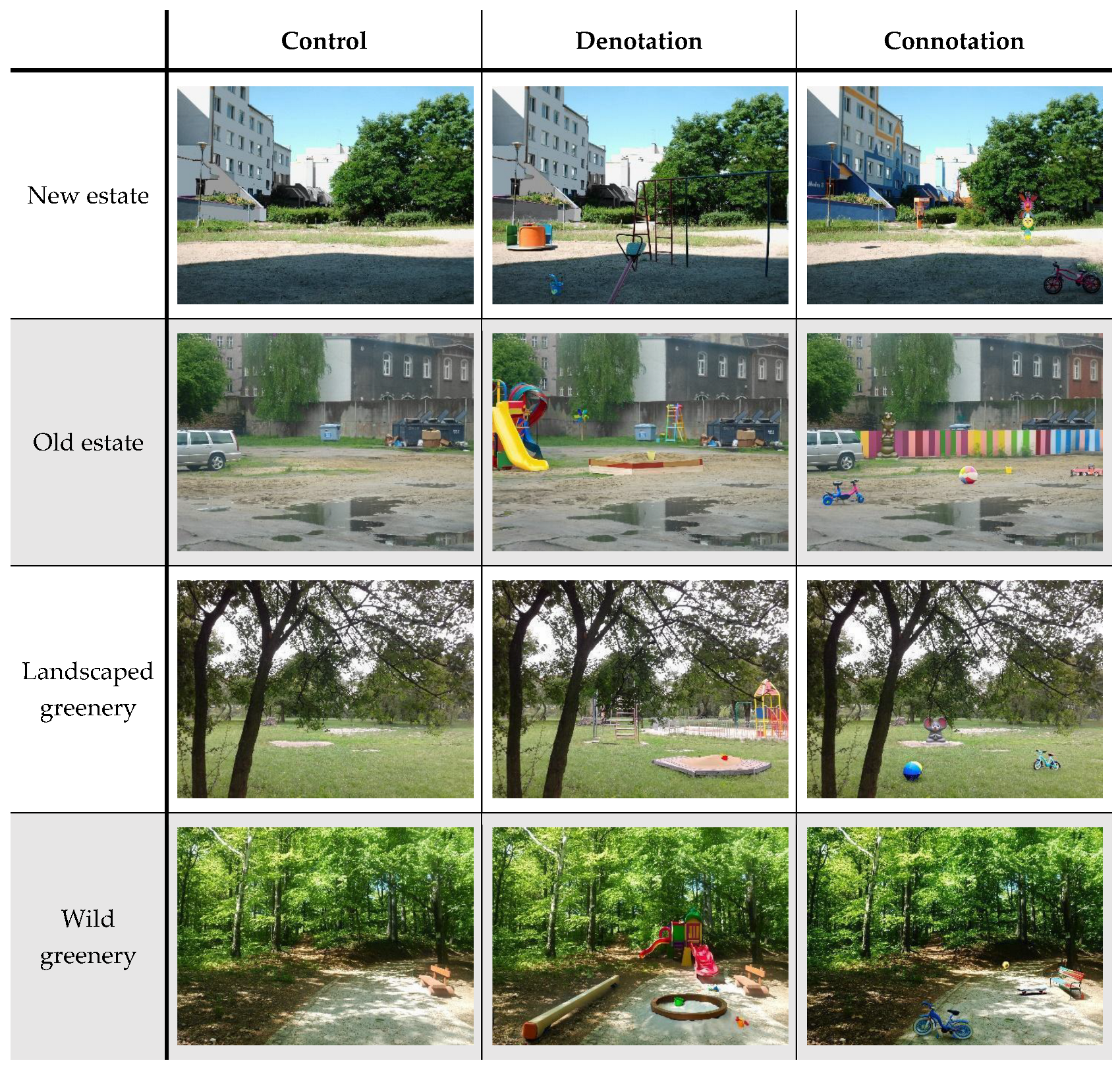

2.1. Research Plan

2.2. Survey Design

2.3. Sampling Method

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Testing the Research Hypotheses for Green Areas

3.3. Testing the Research Hypotheses for Urban Housing Estates

4. Discussion

4.1. How Signs of Children’s Presence Affect Safety

4.2. How Signs of Children’s Presence Affect Preference

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- In housing estates, spaces with the connotation of children’s presence were assessed as the safest—adding children’s paraphernalia to a given area did not significantly increase the sense of safety;

- In housing estates, adding signs of children’s presence boosted their attractiveness, but only among women, while children’s playground equipment enhanced the attractiveness ratings to a lesser extent than elements indirectly associated with children (connotative);

- Adding signs of children’s presence to green areas had no effect on women’s feelings, whereas among men, they undermined sense of safety and preference;

- In general, traditional features associated with children (vivid colours, playground style) have a better effect on women than on men.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Long, Y. Measuring Physical Disorder in Urban Street Spaces: A Large-Scale Analysis Using Street View Images and Deep Learning. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2023, 113, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, R.; Valera Pertegas, S.; Guardia Olmos, J. Feeling Unsafe in Italy’s Biggest Cities. Eur. J. Criminol. 2022, 19, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Liu, L.; Zhou, S.; Song, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, R. Assessing the Impact of Street-View Greenery on Fear of Neighborhood Crime in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health a conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De’Carli, N.; Humanes, M.P. The Account of Urban Violence: Numbers, Statements and Omissions in a Marginalized Brazilian Community. In Violence in the Contemporary World: An Interdisciplinary Approach; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, M.; Chandola, T.; Marmot, M. Association between Fear of Crime and Mental Health and Physical Functioning. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.; Stafford, M. Public Health and Fear of Crime: A Prospective Cohort Study. Br. J. Criminol. 2009, 49, 832–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schertz, K.E.; Saxon, J.; Cardenas-Iniguez, C.; Bettencourt, L.M.; Ding, Y.; Hoffmann, H.; Berman, M.G. Neighborhood street activity and greenspace usage uniquely contribute to predicting crime. Npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, A.; Filipović, B. Neighbourhood, Crime and Fear: Exploring Subjective Perception of Security in Serbia. Nauka Bezb. Polic. 2024, 30, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, M.; Wunas, S.; Osman, W.W.; Lakatupa, G.; Ananda, S.N.F.; Zahirah, A.N. The Resident’s Perception of Security in the Housing That Applies Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) in Makassar City. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2543. [Google Scholar]

- Cozens, P.; Love, T. A Review and Current Status of Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED). J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiahene-Gyamfi, J. Interpersonal Violent Crime in Ghana: The Case of Assault in Accra. J. Crim. Justice 2007, 35, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, V. The Nature of Rape Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newgard, C.D.; Sanchez, B.J.; Bulger, E.M.; Brasel, K.J.; Byers, A.; Buick, J.E.; Sheehan, K.L.; Guyette, F.X.; King, R.V.; Mena-Munoz, J.; et al. A Geospatial Analysis of Severe Firearm Injuries Compared to Other Injury Mechanisms: Event Characteristics, Location, Timing, and Outcomes. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, S.; Giles-Corti, B. The Built Environment, Neighborhood Crime and Constrained Physical Activity: An Exploration of Inconsistent Findings. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D. Neighborhood and Individual Factors in Activity in Older Adults: Results from the Neighborhood and Senior Health Study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2008, 16, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes de Leon, C.F.; Cagney, K.A.; Bienias, J.L.; Barnes, L.L.; Skarupski, K.A.; Scherr, P.A.; Evans, D.A. Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Disorder in Relation to Walking in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Multilevel Analysis. J. Aging Health 2009, 21, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, C.L.; Carlson, N.E.; Bosworth, M.; Michael, Y.L. The Relation between Neighborhood Built Environment and Walking Activity among Older Adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 168, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, V.; Kendal, D.; Hahs, A.K.; Threlfall, C.G. Green Space Context and Vegetation Complexity Shape People’s Preferences for Urban Public Parks and Residential Gardens. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawshalya, L.; Dharmasena, J. To See Without Being Seen: Landscape Perception and Human Behaviour in Urban Parks. Cities People Places Int. J. Urban Environ. 2019, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, B.; Roca, J. Assessing Urban Greenery Using Remote Sensing. In Earth Observing Systems XXVII; SPIE: Nuremberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 12232, pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Fara, G.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S. Green Areas and Public Health: Improving Wellbeing and Physical Activity in the Urban Context. Epidemiol. E Prev. 2015, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, B.; Zaunbrecher, B.S.; Paas, B.; Ottermanns, R.; Ziefle, M.; Roß-Nickoll, M. Assessment of Urban Green Space Structures and Their Quality from a Multidimensional Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1364–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrbe, R.-U.; Neumann, I.; Grunewald, K.; Brzoska, P.; Louda, J.; Kochan, B.; Macháč, J.; Dubová, L.; Meyer, P.; Brabec, J.; et al. The Value of Urban Nature in Terms of Providing Ecosystem Services Related to Health and Well-Being: An Empirical Comparative Pilot Study of Cities in Germany and the Czech Republic. Land 2021, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S.; Brussoni, M. Beyond Physical Activity: The Importance of Play and Nature-Based Play Spaces for Children’s Health and Development. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, S.E.; Hull, R.B. Effects of Vegetation on Crime in Urban Parks; U.S. Forest Service and the International Society of Arboriculture: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, S.E.; Hull, R.B.; Zahm, D.L. Environmental Factors Influencing Auto Burglary: A Case Study. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassels, D.; Guaralda, M. Environment and Interaction: A Study in Social Activation of the Public Realm. _Bo Ric. E Progett. Per Il Territ. La Citta E L’architettura 2013, 4, 104–113. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/219359/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Environment and Crime in the Inner City: Does Vegetation Reduce Crime? Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zienowicz, M.; Błachnio, A. Lighting Features Affecting the Well-Being of Able-Bodied People and People with Physical Disabilities in the Park in the Evening: An Integrated and Sustainable Approach to Lighting Urban Green Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zienowicz, M.; Kukowska, D.; Zalewska, K.; Iwankowski, P.; Shestak, V. How to Light up the Night? The Impact of City Park Lighting on Visitors’ Sense of Safety and Preferences. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 89, 128124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.H.; Byun, G.; Ha, M. Young Women’s Site-Specific Fear of Crime within Urban Public Spaces in Seoul. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruthaveeran Sreetheran, M.S.; van den Bosch, C. A Socio-Ecological Exploration of Fear of Crime in Urban Green Spaces-a Systematic Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groshong, L.; Wilhelm Stanis, S.A.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Hipp, J.A. Attitudes about Perceived Park Safety among Residents in Low-Income and High Minority Kansas City, Missouri, Neighborhoods. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türtseven Doğrusoy, İ.; Zeynel, R. Analysis of Perceived Safety in Urban Parks: A Field Study in Büyükpark and Hasanağa Park. METU J. Fac. Archit. 2017, 34, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Westermann, J.R.; Kowarik, I.; Van der Meer, E. Perceptions of Parks and Urban Derelict Land by Landscape Planners and Residents. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; Hitchmough, J.; Dunnett, N. Woodland as a Setting for Housing-Appreciation and Fear and the Contribution to Residential Satisfaction and Place Identity in Warrington New Town, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; Hitchmough, J.; Calvert, T. Woodland Spaces and Edges: Their Impact on Perception of Safety and Preference. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 60, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zalewska, K.; Pardela, Ł.; Adamczak, E.; Cenarska, A.; Bławicka, K.; Brzegowa, B.; Matiiuk, A. How the Amount of Greenery in City Parks Impacts Visitor Preferences in the Context of Naturalness, Legibility and Perceived Danger. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardela, Ł.; Lis, A.; Iwankowski, P.; Wilkaniec, A.; Theile, M. The Importance of Seeking a Win-Win Solution in Shaping the Vegetation of Military Heritage Landscapes: The Role of Legibility, Naturalness and User Preference. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 221, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.; Schmalz, D.; Larson, L.; Fernandez, M. Fear of the Unknown: Examining Neighborhood Stigma’s Effect on Urban Greenway Use and Surrounding Communities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2021, 57, 1015–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.; Byrne, M.; Carnegie, A. Combatting Stigmatisation of Social Housing Neighbourhoods in Dublin, Ireland. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2019, 19, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Rivera, M.; Uzzell, D.; Brown, J. Perceptions of Disorder, Risk and Safety: The Method and Framing Effects. Psyecology 2011, 2, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.B.; Perkins, D.D.; Brown, G. Incivilities, Place Attachment and Crime: Block and Individual Effects. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.Q.; Kelling, G.L. “Broken windows”: Atlantic monthly. In The City Reader; Routledge: Abington, UK, 1982; pp. 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.B.; Lawton, B.A.; Taylor, R.B.; Perkins, D.D. Multilevel Longitudinal Impacts of Incivilities: Fear of Crime, Expected Safety, and Block Satisfaction. J. Quant. Criminol. 2003, 19, 237–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W. Systematic Social Observation of Public Spaces: A New Look at Disorder in Urban Neighborhoods. Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 105, 603–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, J.C. The Relationship between Disorder, Perceived Risk, and Collective Efficacy: A Look into the Indirect Pathways of the Broken Windows Thesis. Crim. Justice Stud. 2013, 26, 408–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Han, B.; Derose, K.P.; Williamson, S.; Marsh, T.; Raaen, L.; McKenzie, T.L. The Paradox of Parks in Low-Income Areas: Park Use and Perceived Threats. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, B.S.; May, D. College Students’ Crime-Related Fears on Campus: Are Fear-Provoking Cues Gendered? J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2009, 25, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, J. Young People, Policing and Urban Space: A Case Study of the Manchester Millennium Quarter. Safer Communities 2008, 7, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S.; Hassan, R. Gendered Public Spaces and the Geography of Fear in Greater Cairo Slums. Glob. Soc. Welf. 2022, 9, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodó-de-Zárate, M.; Estivill i Castany, J.; Eizagirre, N. Configuration and Consequences of Fear in Public Space from a Gender Perspective. Rev. Española De Investig. Sociológicas 2019, 167, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Vetro, A.; Concha, P. Building Safer Public Spaces: Exploring Gender Difference in the Perception of Safety in Public Space through Urban Design Interventions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharides-Feldman, O.; King, J. ‘There’s Nowhere for Us’: Spatial and Scalar Experiences of Judgement amongst Young Women in the UK. Gend. Dev. 2024, 32, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Tejera, F. Differences between Users of Six Public Parks in Barcelona Depending on the Level of Perceived Safety in the Neighborhood. Athenea Digit. 2012, 12, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi, P.K.; McDermott, R.; Eaves, L.J.; Kendler, K.S.; Neale, M.C. Fear as a Disposition and an Emotional State: A Genetic and Environmental Approach to out-Group Political Preferences. Am. J. Political Sci. 2013, 57, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Abdullah, A.; Mustafa, R.A.; Jayaraman, K.; Bagheri, A. The Importance of Well-Designed Children’s Play-Environments in Reducing Parental Concerns. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2012, 11, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, G. Public Space and the Culture of Childhood; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Walkerdine, V. Safety and Danger: Childhood, Sexuality, and Space at the End of the Millennium. In Governing the Child in the New Millennium; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Senda, M. Safety in Public Spaces for Children’s Play and Learning. IATSS Res. 2015, 38, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, J.; Khatri, R. The Sexual Street Harassment Battle: Perceptions of Women in Urban India. J. Adult Prot. 2018, 20, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.A.; Wahab, M.H.; Rani, W.N.M.W.M.; Ismail, S. Safety of Street: The Role of Street Design. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Şenol, F. Gendered Sense of Safety and Coping Strategies in Public Places: A Study in Atatürk Meydanı of Izmir. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2022, 16, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaştaş-Uzun, İ.; Şenol, F. Contradicting Parochial Realms in Neighborhood Parks: How the Park Attributes Shape Women’s Park Use. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2023, 20, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Almahmood, M.; Carstensen, T.A.; Jørgensen, G. Exploring Adults’ Passive Experience of Playing Children in Cities: Case Study of an Urban Public Space with Open and Integrated Settings in Copenhagen, Denmark. Cities 2024, 145, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Jensen, F.S.; Carstensen, T.A.; Jørgensen, G. Exploring Adults’ Passive Experience of Children Playing in Cities: Case Study of Five Urban Public Open Spaces in Copenhagen, Denmark. Cities 2023, 136, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noschis, K. La Ville, Un Terrain de Jeu Pour l’enfant. Enfances Psy 2006, 33, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M. Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behav. Brain Sci. 1989, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöbaum, A.; Hunecke, M. Perceived Danger in Urban Public Space: The Impacts of Physical Features and Personal Factors. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Analysing Gender Differences in the Perceived Safety from Street View Imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Haandrikman, K. Gendered fear of crime in the urban context: A comparative multilevel study of women’s and men’s fear of crime. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 45, 1238–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Polko, P.; Kimic, K. Gender as a Factor Differentiating the Perceptions of Safety in Urban Parks. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rišová, K.; Madajová, M.S. Gender Differences in a Walking Environment Safety Perception: A Case Study in a Small Town of Banská Bystrica (Slovakia). J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 85, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMousa, N.; Althabet, N.; AlSultan, S.; Albagmi, F.; AlNujaidi, H.; Salama, K.F. Occupational Safety Climate and Hazards in the Industrial Sector: Gender Differences Perspective, Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordellieri, P.; Baralla, F.; Ferlazzo, F.; Sgalla, R.; Piccardi, L.; Giannini, A.M. Gender Effects in Young Road Users on Road Safety Attitudes, Behaviors and Risk Perception. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.J. Gender, Sexual Danger and the Everyday Management of Risks: The Social Control of Young Females. J. Gend. Based Violence 2019, 3, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetchenhauer, D.; Buunk, B.P. How to explain gender differences in fear of crime: Towards an evolutionary approach. Sex. Evol. Gend. 2005, 7, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Jin, S. Evolutionary and cultural psychological perspectives of risk taking. In Psychology of Risk-Taking; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.D., Jr.; Maner, J.K. Male risk-taking as a context-sensitive signaling device. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlow, A. A Geography of Men’s Fear. Geoforum 2005, 36, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkweather, S. Gender, Perceptions of Safety and Strategic Responses among Ohio University Students. Gend. Place Cult. 2007, 14, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braçe, O.; Garrido-Cumbrera, M.; Correa-Fernández, J. Gender Differences in the Perceptions of Green Spaces Characteristics. Soc. Sci. Q. 2021, 102, 2640–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.J.; Jacobs, L.F. Sex Differences in Directional Cue Use in a Virtual Landscape. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 123, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrey, S.; Berthoz, A. Gender Differences in the Use of External Landmarks versus Spatial Representations Updated by Self-Motion. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2007, 6, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Han, G.; Rhee, J.H.; Lee, K.H. Gender Disparities in Perceived Visibility and Crime Anxiety in Piloti Parking Spaces of Multifamily Housing: A Virtual Reality Study. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 14, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarashkar, M.; Hami, A.; Namin, F.E. The Effects of Parks’ Landscape Characteristics on Women’s Perceptual Preferences in Semi-Arid Environments. J. Arid Environ. 2020, 174, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.L.; Julian, D.; Buchman, S.; Humphreys, D.; Mrohaly, M. The Emotional Quality of Scenes and Observation Points: A Look at Prospect and Refuge. Landsc. Plan. 1983, 10, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Pardela, Ł.; Iwankowski, P.; Haans, A. The Impact of Plants Offering Cover on Female Students’ Perception of Danger in Urban Green Spaces in Crime Hot Spots. Landsc. Online 2021, 91, 202191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Su, F.; Han, X.; Fu, Q.; Liu, J. Uncovering the Drivers of Gender Inequality in Perceptions of Safety: An Interdisciplinary Approach Combining Street View Imagery, Socio-Economic Data and Spatial Statistical Modelling. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 134, 104230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K.; Stump, C.; Carreon, D. Confrontation and Loss of Control: Masculinity and Men’s Fear in Public Space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.R.; Baghi, E.S.M.S.; Shams, F.; Jangjoo, S. Women in a Safe and Healthy Urban Environment: Environmental Top Priorities for the Women’s Presence in Urban Public Spaces. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Jahangir, S.; Bailey, A.; van Noorloos, F. Visibility Matters: Constructing Safe Passages on the Streets of Kolkata. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 46, 1265–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Bailey, A.; Lee, J.B. Women’s Perceived Safety in Public Places and Public Transport: A Narrative Review of Contributing Factors and Measurement Methods. Cities 2025, 156, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E. Safe and Inclusive Urban Public Spaces: A Gendered Perspective. The Case of Attica’s Public Spaces During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2023, 33, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snedker, K.A. Neighborhood Conditions and Fear of Crime: A Reconsideration of Sex Differences. Crime Delinq. 2015, 61, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, X. Safety–Premise for Play: Exploring How Characteristics of Outdoor Play Spaces in Urban Residential Areas Influence Children’s Perceived Safety. Cities 2024, 152, 105236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, E.; Krishna, A.; Ardelet, C.; Decré, G.B.; Goudey, A. “Sound and Safe”: The Effect of Ambient Sound on the Perceived Safety of Public Spaces. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benwell, M.C. Rethinking Conceptualisations of Adult-Imposed Restriction and Children’s Experiences of Autonomy in Outdoor Space. Child. Geogr. 2013, 11, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, L.; Hellenius, M.-L.; Nyberg, G.; Andermo, S. Building a Healthy Generation Together: Parents’ Experiences and Perceived Meanings of a Family-Based Program Delivered in Ethnically Diverse Neighborhoods in Sweden. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusafıeh, S.; Muwahıd, N.; Muwahıd, R.; Alhawatmah, L. The effectiveness of kindergarten buildings in Jordan: Shaping the future toward child-friendly architecture. Eurasia Proc. Sci. Technol. Eng. Math. 2022, 17, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, C. Built and natural environmental correlates of parental safety concerns for children’s active travel to school. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 17, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Aziz, N.F.; Shen, H.; Rong, W.; Huang, M. Assessment of Child-Friendliness in Neighbourhood Street Environments in Nanchang, China: An Intersectional Perspective of Affordability, School Trips and Place Identity. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 19, 190904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastgo, P.; Hajzeri, A.; Ahmadi, E. Exploring the opportunities and constraints of urban small green spaces: An investigation of affordances. Child. Geogr. 2024, 22, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellair, P.E. Informal Surveillance and Street Crime: A Complex Relationship. Criminology 2000, 38, 137–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961; Volume 21, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design; Collier Books: The Bronx, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, C.R.; Bohnert, A.M.; Gerstein, D.E. Green Schoolyards in Low-Income Urban Neighborhoods: Natural Spaces for Positive Youth Development Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X. Protecting and Scaffolding: How Parents Facilitate Children’s Activities in Public Space in Urban China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2022, 5, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristianti, N.S.; Widjajanti, R. The Effectiveness of Inclusive Playground Usage for Children through Behavior-Setting Approach in Tembalang, Semarang City. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 592, p. 012027. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, R.; Hanom, I.; Salayanti, S. The Influence of Children’s Playroom Interior Aspect in Regard to Parental Safety Perception. Case Study: Children’s Playroom at 23 Paskal Bandung, Indonesia. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2020, 20, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiro, A.; Nakas, E.; Arslanagic, A.; Markovic, N.; Dzemidzic, V. Perception of Dentofacial Aesthetics in School Children and Their Parents. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 013–019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senzaki, S.; Masuda, T.; Nand, K. Holistic versus Analytic Expressions in Artworks: Cross-Cultural Differences and Similarities in Drawings and Collages by Canadian and Japanese School-Age Children. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 1297–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, J.; Stoltz, T. Perceptions of Beauty Standards among Children. Psicol. Esc. E Educ. 2020, 24, e210192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szechter, L.E.; Liben, L.S. Children’s Aesthetic Understanding of Photographic Art and the Quality of Art-Related Parent–Child Interactions. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidabrienė, J. Development of Aesthetic Perception in 4-8-Year-Old Children Using the Method of Observing Artworks. Acta Paedagog. Vilnensia 2024, 52, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwasing, W.; Sahachaisaeree, N.; Hapeshi, K. Design Goals and Attention Differentiations among Target Groups: A Case of Toy Packaging Design Attracting Children and Parents’ Purchasing Decision. Des. Princ. Pract. Int. J. Annu. Rev. 2013, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R. Children’s Images of Beauty: Environmental Influences on Aesthetic Preferences. Educcation 3-13 2019, 47, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidenbauer, K.L.; Stenfors, C.U.; Young, J.; Layden, E.A.; Schertz, K.E.; Kardan, O.; Decety, J.; Berman, M.G. The Gradual Development of the Preference for Natural Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Dong, Q.; Luo, S.; Jiang, W.; Hao, M.; Chen, Q. Effects of Spatial Elements of Urban Landscape Forests on the Restoration Potential and Preference of Adolescents. Land 2021, 10, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, K.L.; Freeman, C.; Seddon, P.J.; Recio, M.R.; Stein, A.; Van Heezik, Y. The Importance of Urban Gardens in Supporting Children’s Biophilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januškienė, E.; Kamičaitytė, J. Landscape Perception of Children under the Age of 12 Living in Different Settings: A Systematic Review. Archit. Urban Plan. 2024, 20, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz de Tejada Granados, C.; Santo-Tomás Muro, R.; Rodríguez Romero, E.J. Exploring Landscape Preference through Photo-Based Q Methodology. Madrid Seen by Suburban Adolescents. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2021, 30, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müderrisoğlu, H.; Gültekin, P.G. Understanding the Children’s Perception and Preferences on Nature-Based Outdoor Landscape. Indoor Built Environ. 2015, 24, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Gao, M.; Luo, D.; Zhou, X. The Influence of Outdoor Play Spaces in Urban Parks on Children’s Social Anxiety. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1046399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Gao, M.; Luo, D.; Zhou, X. Urban Parks—A Catalyst for Activities! The Effect of the Perceived Characteristics of the Urban Park Environment on Children’s Physical Activity Levels. Forests 2023, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, M. Triangulation Study of Water Play in Urban Open Spaces in Sheffield: Children’s Experiences, Parental and Professional Understanding and Control. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2019, 16, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Y.; He, T. Unveiling the Magic of Mega-City Block Environments: Investigating the Intriguing Mechanisms Shaping Children’s Spontaneous Play Preferences. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1354236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, T.; Tian, J.; Zhou, H. Interactive Design of Children’s Creative Furniture in Urban Community Space. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 671–677. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, H. Landscape Design for Children and Their Environments in Urban Context. In Advances in Landscape Architecture; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mazuelos, G.V.; Chavez, E.M.; Zuñiga, M.A.V.; Chavez, S.M. Ambientes Sistematizados de Atención Para Niños Menores de 5 Años. Rev. Ibérica De Sist. E Tecnol. De Informação 2021, E44, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Kanai, H.; Wang, T.Y.; Yuizono, T. Effects of Landscape Types on Children’s Stress Recovery and Emotion. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørgen, K. Physical Activity in Light of Affordances in Outdoor Environments: Qualitative Observation Studies of 3–5 Years Olds in Kindergarten. Springerplus 2016, 5, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthaler, T.; Lynch, H.; Loebach, J.; Pentland, D.; Schulze, C. Using the Theory of Affordances to Understand Environment–Play Transactions: Environmental Taxonomy of Outdoor Play Space Features—A Scoping Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 78, 7804185120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, S.; Saeedi, S. Investigating the Effect of Urban Landmarks on Children’s Way-Finding (Case Study: Sajjad Neighborhood of Mashhad). Motaleate Shahri 2022, 11, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe, K.; Rathnayake, R.; Wickramaarachchi, N. An Investigation of the Open Spaces and Their Impact on Child Interaction in High-Rise Urban Environments: A Case of the City of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Int. Plan. Stud. 2024, 29, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Research on the Space Design of Kindergarten Activity Unit Example of Graduation Design of South China University of Technology. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019), Moscow, Russia, 14–16 May 2019; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 545–554. [Google Scholar]

- Ripat, J.; Becker, P. Playground Usability: What Do Playground Users Say? Occup. Ther. Int. 2012, 19, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajide, B.V. Ecosophy Applied to Spatial Design for Child Development. A Proposal to Bridge the Gap Between Legislation and Architectural Design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainability: Developments and Innovations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Inginitskaya, D.; Antonov, I.; Belyaeva, L.; Zhukova, T. City Education: Everything About Playgrounds; Springer Geography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, N.; Ibrahim, R.; Abidin, S.Z. Transformation of Children’s Paintings into Public Art to Improve Public Spaces and Enhance People’s Happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, H.; Li, X.; Zeng, S. Unraveling the Mediating Role of Plant Color and Familiarity on Children’s Mood in Urban Landscape. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Å.O.; Knez, I.; Gunnarsson, B.; Hedblom, M. The Effects of Naturalness, Gender, and Age on How Urban Green Space Is Perceived and Used. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 18, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Y.; Keshavarzi, G.; Aman, A.R. Does Play-Based Experience Provide for Inclusiveness? A Case Study of Multi-Dimensional Indicators. Child Indic. Res. 2022, 15, 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Luo, Y.; Furuya, K. Gender Differences and Optimizing Women’s Experiences: An Exploratory Study of Visual Behavior While Viewing Urban Park Landscapes in Tokyo, Japan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, M.V.; Samper, P.; Frías, M.D.; Tur, A.M. Are Women More Empathetic than Men? A Longitudinal Study in Adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 2009, 12, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, T.R.; Kropscott, L.S. Legibility, Mystery, and Visual Access as Predictors of Preference and Perceived Danger in Forest Settings without Pathways. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Iwankowski, P. Where Do We Want to See Other People While Relaxing in a City Park? Visual Relationships with Park Users and Their Impact on Preferences, Safety and Privacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardela, Ł.; Lis, A.; Zalewska, K.; Iwankowski, P. How Vegetation Impacts Preference, Mystery and Danger in Fortifications and Parks in Urban Areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Flynn-Smith, J.A. Preference and Perceived Danger as a Function of the Perceived Curvature, Length, and Width of Urban Alleys. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova, B.; Briggs, A.; O’Hagan, A.; Thompson, S.G. Review of Statistical Methods for Analysing Healthcare Resources and Costs. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 897–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanca Mena, M.J.; Alarcón Postigo, R.; Arnau Gras, J.; Bono Cabré, R.; Bendayan, R. Non-Norm. Data: Is ANOVA Still A Valid Option? Psicothema 2017, 29, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.D.; Ross, C.E.; Angel, R.J. Neighborhood Disorder, Psychophysiological Distress, and Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ream, M.; Plotke, R.; Taub, C.J.; Borowsky, P.A.; Hernandez, A.; Blomberg, B.; Goel, N.; Antoni, M.H. Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management Effects on Cancer-Related Distress and Neuroendocrine Signaling in Breast Cancer: Differential Effects by Neighborhood Disadvantage. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 211, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemzadeh, K. Assessing E-Scooter Rider Safety Perceptions in Shared Spaces: Evidence from a Video Experiment in Sweden. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 211, 107874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouz, J.; Píšová, M.; Urban, J. Perception of Natural Ecosystems and Urban Greenery: Are We Afraid of Nature? Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 12, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Fors, H.; Lindgren, T.; Wiström, B. Perceived Personal Safety in Relation to Urban Woodland Vegetation–A Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Karolina, Z. Surveillance as a Variable Explaining Why Other People’s Presence in a Park Setting Affects Sense of Safety and Preferences. Landsc. Online 2024, 99, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Zalewska, K.; Grabowski, M. The Ability to Choose How to Interact with Other People in the Park Space and Its Role in Terms of Perceived Safety and Preference. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 99, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Andrews, M. Human Experiences in Dense and Open Woodland; the Role of Different Danger Threats. Trees For. People 2023, 14, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Tu, H.-M.; Ho, C.-I. Understanding Biophilia Leisure as Facilitating Well-Being and the Environment: An Examination of Participants’ Attitudes toward Horticultural Activity. Leis. Sci. 2013, 35, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pasanen, T.; Johnson, K.; Lee, K.; Korpela, K. Can Nature Walks with Psychological Tasks Improve Mood, Self-Reported Restoration, and Sustained Attention? Results from Two Experimental Field Studies. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.; Furuya, K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, J. The Restorative Potential of Green Cultural Heritage: Exploring Cultural Ecosystem Services’ Impact on Stress Reduction and Attention Restoration. Forests 2023, 14, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.P.; Schilhab, T.; Bentsen, P. Attention Restoration Theory II: A Systematic Review to Clarify Attention Processes Affected by Exposure to Natural Environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2018, 21, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopcroft, R. Evolution and Gender: Why It Matters for Contemporary Life; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Aguilar, A.; Barrios, F.A. A preliminary study of sex differences in emotional experience. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 118, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.L.; Goodmon, L.B.; Hester, S. The Burtynsky Effect: Aesthetic Reactions to Landscape Photographs That Vary in Natural Features. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2018, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; He, X.; Liu, S.; Li, T.; Li, J.; Tang, X.; Lai, S. Neural Correlates of Appreciating Natural Landscape and Landscape Garden: Evidence from an fMRI Study. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Hu, B. Design Intensities in Relation to Visual Aesthetic Preference. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 34, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Hauer, R.J.; Xu, C. Effects of Design Proportion and Distribution of Color in Urban and Suburban Green Space Planning to Visual Aesthetics Quality. Forests 2020, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, C.; Warusavitharana, E.J.; Ratnayake, R. An Examination of the Temporal Effects of Environmental Cues on Pedestrians’ Feelings of Safety. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 64, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carles, J.L.; Barrio, I.L.; De Lucio, J.V. Sound Influence on Landscape Values. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 43, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Półrolniczak, M.; Kolendowicz, L. The Influence of Weather and Level of Observer Expertise on Suburban Landscape Perception. Build. Environ. 2021, 202, 108016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, S.; Calautit, J.K.; Hughes, B.R.; Satish, B.; Rijal, H.B. Patterns of Thermal Preference and Visual Thermal Landscaping Model in the Workplace. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, H.; Lin, B. Olfactory effect on landscape preference. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. (EEMJ) 2018, 17, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Liang, H.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, L. Comparisons of Landscape Preferences through Three Different Perceptual Approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Cioffi, F.; Li, J.; Maffei, L.; Scorpio, M.; Iachini, T.; Ruggiero, G.; Malferà, A.; Ruotolo, F. An Investigation of the Influence of the Night Lighting in a Urban Park on Individuals’ Emotions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J. Demographic groups’ differences in visual preference for vegetated landscapes in urban green space. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 28, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hami, A.; Tarashkar, M.; Emami, F. The relationship between women’s preferences for landscape spatial configurations and relevant socio-economic variables. Arboric. Urban For. (AUF) 2020, 46, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Aguilera, P.A.; Montes, C. The role of multi-functionality in social preferences toward semi-arid rural landscapes: An ecosystem service approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 19, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wal, R.; Miller, D.; Irvine, J.; Fiorini, S.; Amar, A.; Yearley, S.; Gill, R.; Dandy, N. The influence of information provision on people’s landscape preferences: A case study on understorey vegetation of deer-browsed woodlands. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 124, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Consensus in factors affecting landscape preference: A case study based on a cross-cultural comparison. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 252, 109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzipanagiotis, M. Informed Consent: Using Behavioral Science to Make It Easier to Accept… and Easier to Nullify at the Court? New Space 2016, 4, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intra-group factors | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of space | Housing estate | Green areas | ||||||||||

| The nature of space | New | Old | Landscaped | Wild | ||||||||

| Inter-group factors | ||||||||||||

| Scenario | Control (without interference) | Denotation | Connotation | |||||||||

| Sex | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | ||||||

| Dependent variables (measured on a Likert scale) | ||||||||||||

| Safety | Answer: ‘Rate how safe or dangerous you would feel in the place from where the photo was taken. Answer the question on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = very dangerous and 5 = very safe’. | |||||||||||

| Preference | Answer: ‘How much do you like the setting? This is your own personal degree of liking for the setting, and you don’t have to worry about whether you’re right or wrong or whether you agree with anybody else. Answer the question on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = not at all and 5 = very much’. | |||||||||||

| Sample selection—procedure steps | ||||||||||||

| 1. Recruitment (invitations to randomly selected respondents) | 360 respondents | |||||||||||

| 2. Division of the selected sample according to sex | 189 women | 171 men | ||||||||||

| 3. Randomisation—random division into three groups | Control 63 women | Denotation 63 women | Connotation 63 women | Control 57 men | Denotation 57 men | Connotation 57 men | ||||||

| 4. Summary: Characteristics of the groups | Three groups (Control/Denotation/Connotation) of 120 people each, including 63 women and 57 men | |||||||||||

| Safety on the housing estate—intra-group effects | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Place | 221.45 | 1 | 221.45 | 676.33 | <0.001 |

| Place * Scenario | 0.79 | 2 | 0.39 | 1.2 | 0.302 |

| Place * Sex | 0.21 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.65 | 0.421 |

| Place * Scenario * Sex | 0.04 | 2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.939 |

| Residual | 115.91 | 354 | 0.33 | ||

| Safety on the housing estate—inter-group effects | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Scenario | 14.15 | 2 | 7.07 | 6.4 | 0.002 |

| Sex | 2.33 | 1 | 2.33 | 2.11 | 0.147 |

| Scenario * Sex | 3.1 | 2 | 1.55 | 1.4 | 0.248 |

| Residual | 391.27 | 354 | 1.11 | ||

| Intra-Group Effects | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Place | 206.71 | 1 | 206.71 | 722.01 | <0.001 |

| Place * Scenario | 1.13 | 2 | 0.57 | 1.98 | 0.14 |

| Place * Sex | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.545 |

| Place * Scenario * Sex | 1.44 | 2 | 0.72 | 2.52 | 0.082 |

| Residual | 101.35 | 354 | 0.29 | ||

| Inter-Group Effects | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Scenario | 15.73 | 2 | 7.87 | 7.7 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 1.59 | 1 | 1.59 | 1.55 | 0.214 |

| Scenario * Sex | 10.41 | 2 | 5.21 | 5.09 | 0.007 |

| Residual | 361.83 | 354 | 1.02 | ||

| Intra-Group Effects | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Place | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.556 |

| Place * Scenario | 6.11 | 2 | 3.05 | 15.51 | <0.001 |

| Place * Sex | 0.37 | 1 | 0.37 | 1.88 | 0.171 |

| Place * Scenario * Sex | 0.24 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.6 | 0.549 |

| Residual | 69.7 | 354 | 0.2 | ||

| Inter-Group Effects | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

| Scenario | 18.33 | 2 | 9.16 | 9.04 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.392 |

| Scenario * Sex | 11.44 | 2 | 5.72 | 5.64 | 0.004 |

| Residual | 358.81 | 354 | 1.01 | ||

| Place | Scenario | Safety | Preference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Man | Women | Man | ||

| Housing estate— old/new | Connotation | ||||

| Denotation | |||||

| Control | |||||

| Green areas— wild | Connotation | ||||

| Denotation | |||||

| Control | |||||

| Green areas —landscaped | Connotation | ||||

| Denotation | |||||

| Control | |||||

| The order of values is in ascending order: a-b-c, the same colour indicating subsequent values that do not differ in a statistically significant way | |||||

| a | b | c | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lis, A.; Zalewska, K.; Grabowski, M.; Zienowicz, M. Signs of Children’s Presence in Two Types of Landscape: Residential and Park: Research on Adults’ Sense of Safety and Preference: Premises for Designing Sustainable Urban Environments. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094098

Lis A, Zalewska K, Grabowski M, Zienowicz M. Signs of Children’s Presence in Two Types of Landscape: Residential and Park: Research on Adults’ Sense of Safety and Preference: Premises for Designing Sustainable Urban Environments. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094098

Chicago/Turabian StyleLis, Aleksandra, Karolina Zalewska, Marek Grabowski, and Magdalena Zienowicz. 2025. "Signs of Children’s Presence in Two Types of Landscape: Residential and Park: Research on Adults’ Sense of Safety and Preference: Premises for Designing Sustainable Urban Environments" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094098

APA StyleLis, A., Zalewska, K., Grabowski, M., & Zienowicz, M. (2025). Signs of Children’s Presence in Two Types of Landscape: Residential and Park: Research on Adults’ Sense of Safety and Preference: Premises for Designing Sustainable Urban Environments. Sustainability, 17(9), 4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094098