Typologies of Transformation—Visualizing Different Understandings of Change for Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

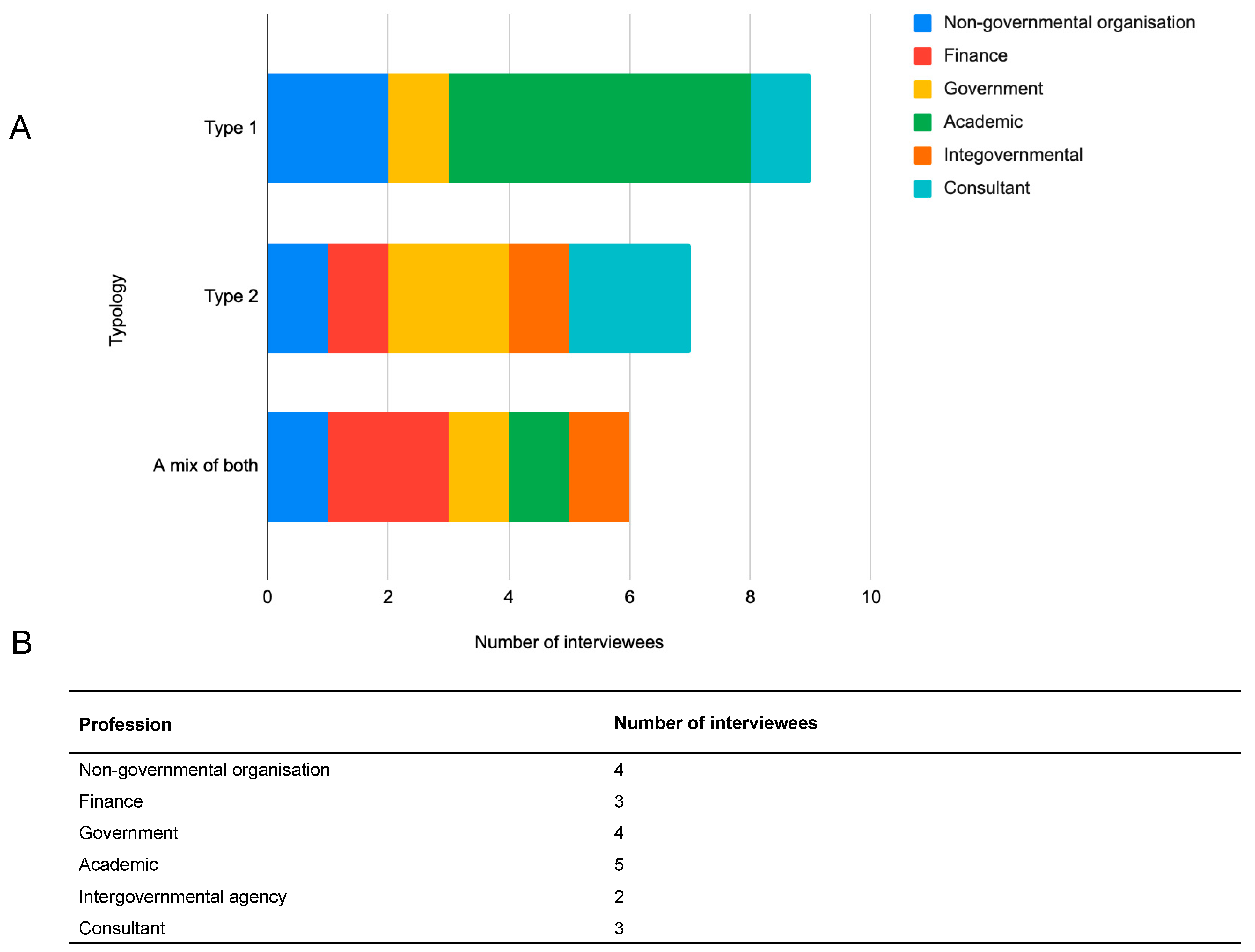

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Setting the Scene

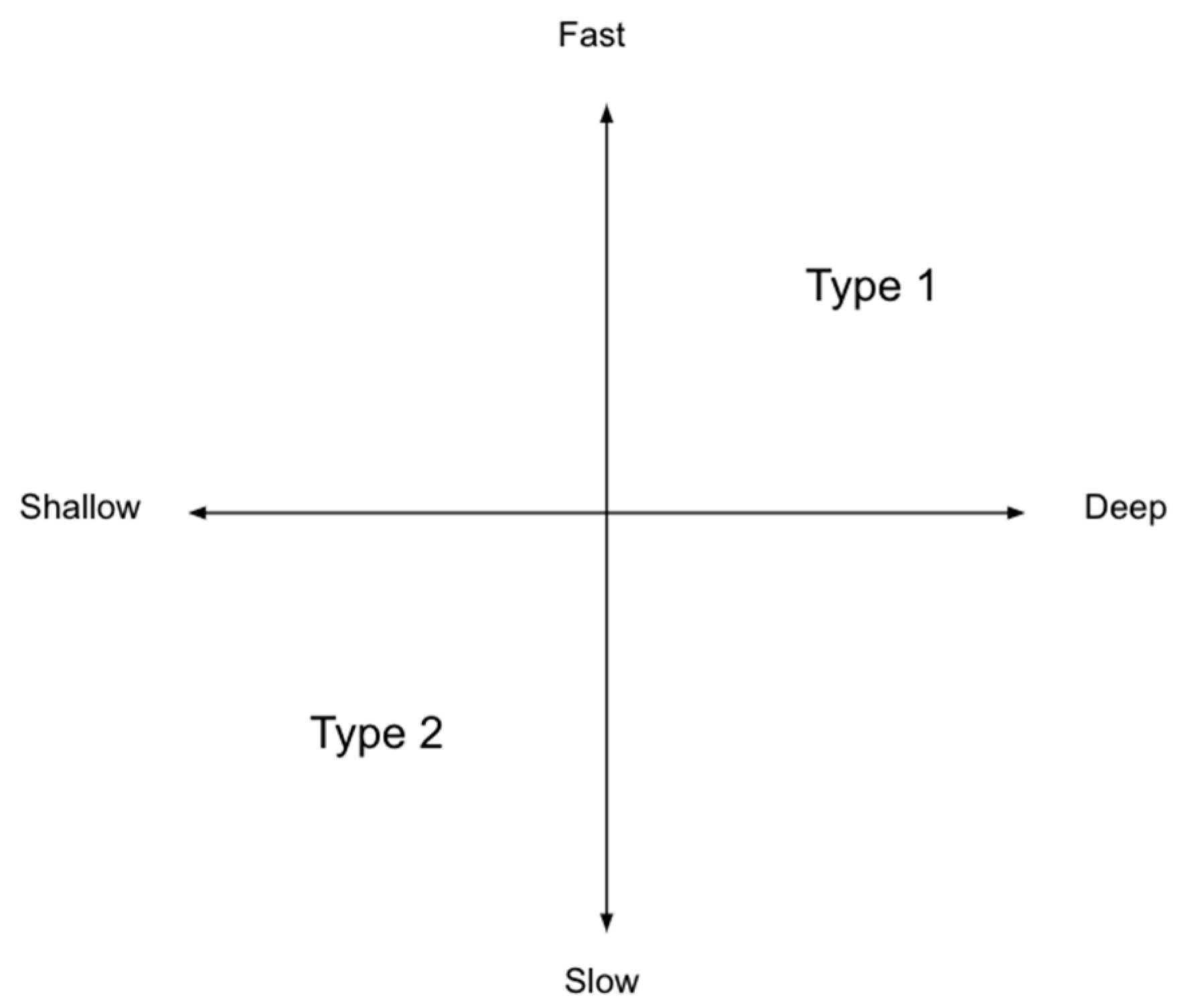

3.2. Type 1 Transformation

3.2.1. Defining Type 1 Transformation

“We believe that only radical reordering of the global hegemony on terms collectively determined and generated is capable of doing justice to a full range of otherwise marginalized experiences, and that such is only possible via methods that are radically collective, relational, power conscious and which maintain an ongoing openness to a complete reformulation.”

3.2.2. Type 1 in Practice

3.3. Type 2 Transformation

3.3.1. Defining Type 2 Transformation

3.3.2. In Practice

3.4. A Mix of Both

Defining a Mix of Both

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heinze, C.; Blenckner, T.; Martins, H.; Rusiecka, D.; Döscher, R.; Gehlen, M.; Gruber, N.; Holland, E.; Hov, Ø.; Joos, F.; et al. The quiet crossing of ocean tipping points. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2008478118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talukder, B.; Ganguli, N.; Matthew, R.; vanLoon, G.W.; Hipel, K.W.; Orbinski, J. Climate change-accelerated ocean biodiversity loss & associated planetary health impacts. J. Clim. Change Health 2022, 6, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Turning the Tide: How to Finance a Sustainable Ocean Recovery; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; van der Leeuw, S.; O’Brien, K.; Berkhout, F.; Biermann, F.; Brondizio, E.S.; Cudennec, C.; Dearing, J.; Duraiappah, A.; Glaser, M.; et al. Plausible and desirable futures in the Anthropocene: A new research agenda. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 39, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; van der Hel, S.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Hurlbert, M.; Anderton, K.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A. Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing nature’s contributions to people: The IPBES approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Kok, M.T.J. The Urgency of Transforming Biodiversity Governance. In Transforming Biodiversity Governance; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J., Kok, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vadrot, A.B.M.; Ruiz Rodríguez, S.C.; Brogat, E.; Paul, D.; Langlet, A.; Tessnow-von Wysocki, I.; Wanneau, K. Towards a reflexive, policy-relevant and engaged ocean science for the UN decade: A social science research agenda. Earth Syst. Gov. 2022, 14, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Level Ocean Panel. Transformations for a Sustainable Ocean Economy: A Vision for Protection, Production and Prosperity. High Level Ocean Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, 2020. Available online: https://oceanpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/transformations-sustainable-ocean-economy-eng.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Evans, T.; Fletcher, S.; Failler, P.; Potts, J. Untangling theories of transformation: Reflections for ocean governance. Mar. Policy 2023, 155, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Social theory and climate change: Questions often, sometimes and not yet asked. Theory Cult. Soc. 2010, 27, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Loorbach, D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Koretskaya, O.; Moore, D. (Un)making in sustainability transformation beyond capitalism. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 69, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalau, J.; Handmer, J. When is transformation a viable policy alternative? Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.; Fletcher, S.; Failler, P.; Fletcher, R.; Potts, J. Radical and incremental, a multi-leverage point approach to transformation in ocean governance. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1243–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.T.V.; Ramcilovic-Suominen, S. From hegemony-reinforcing to hegemony-transcending transformations: Horizons of possibility and strategies of escape. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, J.; O’Brien, K.; Scoville-Simonds, M. Beyond “blah blah blah”: Exploring the “how” of transformation. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. The Power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Critical Inquiry. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoš, P. Who Exactly is an Expert? On the Problem of Defining and Recognizing Expertise. Sociológia-Slovak Sociol. Rev. 2018, 50, 268–288. [Google Scholar]

- Handcock, M.S.; Gile, K.J. Comment: On the Concept of Snowball Sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.; Fletcher, S.; Failler, P.; March, A.; Potts, J. Journeys of change towards the blue economy: Evaluating process in transformational change. Reg Environ. Change 2024, 24, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J. Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 873572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.; Armitage, D.; Bennett, N.; Silver, J.J.; Song, A.M. Conditions and Cautions for Transforming Ocean Governance. In Water Resilience: Management and Governance in Times of Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Chuenpagdee, R.; Isaacs, M.; Bugeja-Said, A.; Jentoft, S. Collective Experiences, Lessons, and Reflections About Blue Justice. In Blue Justice; Jentoft, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Bugeja Said, A., Isaacs, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 26, pp. 657–680. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, M.; O’Brien, K.; Matyas, D. Adaptation and transformation. Clim. Change 2015, 133, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.H.; Adger, W.N.; Agrawal, A.; Brown, K.; Hornsey, M.J.; Hughes, T.P.; Jain, M.; Lemos, M.C.; McHugh, L.H.; O’Neill, S.; et al. Radical interventions for climate-impacted systems. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M. Capitalism and Climate Change: Theoretical Discussion, Historical Development and Policy Responses; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Newell, R.G.; Stavins, R.N. Chapter 11-Technological change and the Environment. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Mäler, K.-G., Vincent, J., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, H.A. Global capitalism and climate change. In Handbook on International Political Economy; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012; pp. 395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, A. The Climate Crisis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.T. Climate change and capitalism. Consilience 2015, 14, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, M.C.; Okereke, J.; Arima, V.; Bosetti, Y.; Chen, J.; Edmonds, S.; Gupta, A.; Köberle, S.; Kverndokk, A.; Malik, L.; et al. Introduction and Framing. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, U.; McElwee, P.D.; Diamond, S.E.; Ngo, H.T.; Bai, X.; William, W.L. Governing for Transformative Change across the Biodiversity–Climate–Society Nexus. BioScience 2022, 72, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J.; Coolsaet, B.; Dawson, N.; Suiseeya, K.M.; Inoue, C.Y.A.; Lim, M. Rethinking and Upholding Justice and Equity in Transformative Biodiversity Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gillard, R.; Gouldson, A.; Paavola, J.; Van Alstine, J. Transformational responses to climate change: Beyond a systems perspective of social change in mitigation and adaptation. WIREs Clim. Change 2016, 7, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W.; Travis, W.R.; Wilbanks, T.J. Transformational adaptation when incremental adaptations to climate change are insufficient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7156–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutting, L.; Vervoort, J.; Mees, H.; Pereira, L.; Veeger, M.; Muiderman, K.; Mangnus, A.; Winkler, K.; Olsson, P.; Hichert, T.; et al. Disruptive seeds: A scenario approach to explore power shifts in sustainability transformations. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Ellis, G.; Flannery, W. Conceptualising change in marine governance: Learning from Transition Management. Mar. Policy 2018, 95, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Sustainability as transmutation: An alchemical interpretation of a transformation to sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, J.; do Carmo, L.; Schafenacker, N.; Schirok, J.; Corso, S.D. Creative, embodied practices, and the potentialities for sustainability transformations. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertör, I.; Hadjimichael, M. Editorial: Blue degrowth and the politics of the sea: Rethinking the blue economy. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.; Silver, J.; Evans, L.; Armitage, D.; Bennett, N.J.; Moore, M.L.; Morrison, T.H.; Brown, K. The Dark Side of Transformation: Latent Risks in Contemporary Sustainability Discourse. Antipode 2018, 50, 1206–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Government. Government of, B. 7th Five Year Plan; Bangladesh Government: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015.

- Bangladesh Government. Government of, B. 8th Five Year Plan; Bangladesh Government: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020.

- Adekunle, I.A.; Oseni, I.O. Fuel subsidies and carbon emission: Evidence from asymmetric modelling. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 22729–22741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blythe, J.; Bennett, N.J.; Blythe, J.L.; Armitage, D.; Bennett, N.J.; Silver, J.J.; Crona, B.I.; Blythe, J.L. The Politics of Ocean Governance Transformations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 634718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinosho, B.; Hamukuaya, H.; Lajaunie, C.; Lancaster, A.; Lennan, M.; Mazzega, P.; Morgera, E.; Snow, B. Transformative Governance for Ocean Biodiversity. In Transforming. Biodiversity. Governance; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J., Kok, M.T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, A.T.; Clifford-Holmes, J.; Goodall, V.; Snow, B.; Truter, H.; Vrancken, P.; Jones, P.J.S.; Cochrane, K.; Flannery, W.; Hicks, C.; et al. Principles for transformative ocean governance. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Hickmann, T.; Sénit, C.-A.; Beisheim, M.; Bernstein, S.; Chasek, P.; Grob, L.; Kim, R.E.; Kotzé, L.J.; Nilsson, M.; et al. Scientific evidence on the political impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Documents Reviewed | Formal Interviews | Informal Conversations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seychelles | 54 | 3 | 8 |

| Bangladesh | 71 | 4 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Evans, T.; Fletcher, S.; Failler, P.; Potts, J. Typologies of Transformation—Visualizing Different Understandings of Change for Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094075

Evans T, Fletcher S, Failler P, Potts J. Typologies of Transformation—Visualizing Different Understandings of Change for Sustainability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094075

Chicago/Turabian StyleEvans, Tegan, Stephen Fletcher, Pierre Failler, and Jonathan Potts. 2025. "Typologies of Transformation—Visualizing Different Understandings of Change for Sustainability" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094075

APA StyleEvans, T., Fletcher, S., Failler, P., & Potts, J. (2025). Typologies of Transformation—Visualizing Different Understandings of Change for Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(9), 4075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094075