Digital Transformation, CEO Compensation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Institutional Background, Theoretical Framework, and Hypothesis Development

2.1. ESG and Sustainability Disclosure

2.2. Theoretical Framework

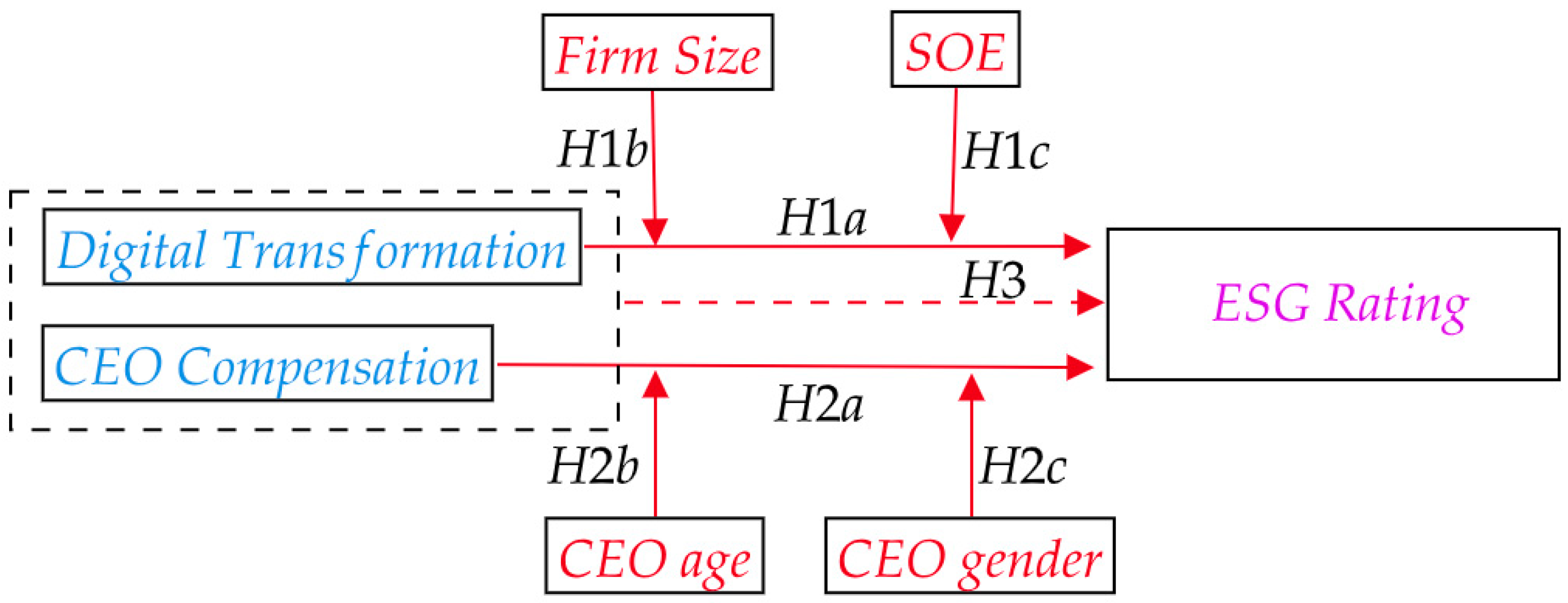

2.3. Digital Transformation and ESG

2.4. CEO Compensation and ESG

2.5. Digital Transformation, CEO Compensation, and ESG Performance

2.6. The Synergistic Effect of Digital Transformation and CEO Compensation

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Econometric Specification

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Digital Transformation and ESG Performance

4.3. CEO Compensation and ESG Performance

4.4. The Joint Effect of Digital Transformation and CEO Compensation on ESG Performance

5. Robustness Test

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Keywords of Firm Digital Transformation

| Concept | Components | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | Concept of digital transformation (7) | Digitalization, digital transformation, datamation, intelligentization, informatization, Internet plus |

| Artificial intelligence (17) | Artificial intelligence, AI, natural language processing, NLP, image identification, image understanding, voice recognition, language identification, language comprehension, face recognition, bioidentification, machine learning, deep learning, expert system, robot, intelligent customer service, digital intelligence | |

| Blockchain (12) | Blockchain, encryption algorithm, digital currency, distributed ledger, distributed database, digital rights management, peer-to-peer networking, peer-to-peer transmission, P2P, Distributed file system | |

| Cloud computing (11) | Cloud computing, cloud service, cloud security, cloud platform, cloud storage, cloud ecology, cloud data, cloud management, intelligent management platform, edge computing | |

| Big data (16) | Big data, data mining, text analysis, data visualization, unstructured data, augmented reality, AR, SQL, data network, data center, data platform, data-driven, computational advertising, simulation technology, virtual reality | |

| Internet of Things (6) | Internet of Things, IoT, transducer, digital sensor, supply chain management, Industrial Internet of Things | |

| Industry 4.0 (23) | Industry 4.0, digital factory, smart factory, intelligent workshop, digital production, intelligent manufacturing, industry robots, industrial Internet, industrial control computer, industrial automatic control system, Human–Computer Interaction, numerical control, digital telecommunications, digital supply chain, computer manufacturing, intelligent device, 3D printing, 3D, digital twins, intelligent controls | |

| Application | Digital application (31) | Firm resource planning, ERP, customer relationship management system, CRM, online retail, Internet sales, unmanned retail, digital finance, intelligent marketing, digital marketing, E-Commerce, Internet finance, mobile payment, third party payment, NFC, B2B, B2C, C2B, C2C, social media, internet ecology, digital network, digital media, quantum teleportation, smart agriculture, intelligent transportation |

References

- Kotsantonis, S.; Serafeim, G. Four things no one will tell you about ESG data. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2019, 31, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kadach, I.; Ormazabal, G.; Reichelstein, S. Executive compensation tied to ESG performance: International evidence. J. Account. Res. 2023, 61, 805–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.L.; Heinle, M.S.; Luneva, I. A theoretical framework for environmental and social impact reporting. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.; Kopytov, A.; Shen, L.; Xiang, H. On ESG investing: Heterogeneous preferences, information, and asset prices. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Lin, H.; Han, W.; Wu, H. ESG in China: A review of practice and research, and future research avenues. China J. Account. Res. 2023, 16, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Ji, H.; Iwata, K.; Arimura, T.H. Do ESG reporting guidelines and verifications enhance firms’ information disclosure? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Hung, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhu, B.; Sun, Y. Digitalization transformation and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huang, M.; Wang, D.; Li, X. Star CEOs and ESG performance in China: An integrated view of role identity and role constraints logics. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 32, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Liu, B.; Zhu, L. STEM CEOs and firm digitalization. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder? The case of ESG ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouvenot, V.; Krueger, P. Mandatory corporate carbon disclosure: Evidence from a natural experiment. SSRN Electron. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Dumay, J. Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental, social and governance reporting in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari, M.A.; Banerjee, S.N.; Rasheed, A.A. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: A theory of dual responsibility. Manag. Decis. 2021, 60, 1513–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Why resource-based theory’s model of profit appropriation must incorporate a stakeholder perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 3305–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.M.; Odean, T. Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Blandon, J.; Argilés-Bosch, J.M.; Ravenda, D. Exploring the relationship between CEO characteristics and performance. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Lan, H. Why and how executive equity incentive influences digital transformation: The role of internal and external governance. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 4217–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, H. Ways to improve the efficiency of clean energy utilization: Does digitalization matter? Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 50, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. Unlocking sustainable value through digital transformation: An examination of ESG performance. Information 2023, 14, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Managiy, S. Disclosure or action: Evaluating ESG behavior towards financial performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 44, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhu, B.; Yang, M.; Chu, X. ESG and financial performance: A qualitative comparative analysis in China’s new energy companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Xiong, W. The impact of digital transformation on corporate environment performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Nie, C. The effect of government informatization construction on corporate digital technology innovation: New evidence from China. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2024, 33, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cai, L. Digital transformation and corporate ESG: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, H. Relationship analysis between executive motivation and digital transformation in Chinese A-Share companies: An empirical study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, G.; Huang, J.; Liu, S. Digital transformation and within-firm pay gap: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 59, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartenberg, C.M.; Wulf, J.M. Competition and pay inequality within and between firms. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 5925–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wang, S.; Li, F. The impact of digital transformation on ESG performance based on the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, Y. A study on the impact of digital transformation on corporate ESG performance: The mediating role of green innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, B.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q. Corporate digital transformation, governance shifts and executive pay-performance sensitivity. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 92, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, L.; He, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, W. Green financial reform and corporate ESG performance in China: Empirical evidence from the green financial reform and innovation pilot zone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Yang, F.; Xiong, L. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance and firm value: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y. Mixed-ownership reform of SOEs and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 1618–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Cirillo, A.; Favino, C.; Netti, A. ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) performance and board gender diversity: The moderating role of CEO duality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabreros, D.; De La Fuente, G.; Velasco, P. From dawn to dusk: The relationship between CEO career horizon and ESG engagement. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xue, L.; Bin, S. Executive compensation and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from China. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.; Cook, A.; Ingersoll, A.R. Do women leaders promote sustainability? Analyzing the effect of corporate governance composition on environmental performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.S.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Orsato, R.J. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Srinivasan, S. Going digital: Implications for firm value and performance. Rev. Account. Stud. 2024, 29, 1619–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J.-M.; Wang, S.; Xu, L. Size and resilience of the digital economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Qi Dong, J.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebbecke, C.; Picot, A. Reflections on societal and business model transformation arising from digitization and big data analytics: A research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhong, H.; Wei, C. Business environment and enterprise digital transformation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, T. The impact of digital transformation on ESG: A case study of Chinese listed companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Abeysekera, I. Financial reporting quality of ESG firms listed in China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, V.; Sostero, M.; Tamagni, F. Innovation and within-firm wage inequalities: Empirical evidence from major European countries. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 468–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | SD | Min | Med | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Words | 16,205 | 40.97 | 61.27 | 0 | 18 | 351 |

| Concept of DT | 16,205 | 14.71 | 21.21 | 1 | 7 | 123.96 |

| AI | 16,205 | 4.07 | 10.03 | 0 | 1 | 67 |

| Blockchain | 16,205 | 0.33 | 1.34 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Cloud Computing | 16,205 | 1.70 | 5.37 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| Big Data | 16,205 | 5.28 | 12.17 | 0 | 1 | 77 |

| Internet of Things | 16,205 | 2.77 | 7.85 | 0 | 0 | 54 |

| Industry 4.0 | 16,205 | 3.99 | 9.23 | 0 | 1 | 61 |

| Digital Application | 16,205 | 5.44 | 10.57 | 0 | 1 | 64 |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | SD | Min | Med | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG Rating | 16,205 | 6 | 0.79 | 4.26 | 5.96 | 8.25 |

| DT_freq | 16,205 | 2.92 | 1.35 | 0 | 2.94 | 5.86 |

| CEO_compensation | 16,205 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 7.18 |

| lnTA | 16,205 | 22.37 | 1.38 | 20.02 | 22.14 | 27.12 |

| SOE | 16,205 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TobinsQ | 16,205 | 1.90 | 1.76 | 0.08 | 1.40 | 10.09 |

| CEO_age | 16,205 | 48.35 | 7.35 | 30 | 49 | 66 |

| CEO_gender | 16,205 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Leverage | 16,205 | 149.74 | 330.61 | −1109.92 | 81.21 | 2031.34 |

| ROE | 16,205 | 5.41 | 16.33 | −85.28 | 7.23 | 41.89 |

| ROA | 16,205 | 3.84 | 7.39 | −27.82 | 3.92 | 23.81 |

| Indirratio | 16,205 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 1 |

| Duality | 16,205 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Listing_tenure | 16,205 | 11.01 | 8.34 | 0.43 | 9.09 | 29.03 |

| ESGRating | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| L.DT_freq | 0.05822 *** | −0.47712 *** | |

| (0.00609) | (0.07912) | ||

| lnTA | 0.14518 *** | 0.13419 *** | 0.06155 *** |

| (0.00810) | (0.00810) | (0.01350) | |

| SOE | 0.04641 * | 0.05383 ** | 0.06892 * |

| (0.02508) | (0.02479) | (0.04055) | |

| L.DT_freq x lnTA | 0.02405 *** | ||

| (0.00359) | |||

| L.DT_freq x SOE | −0.00476 | ||

| (0.01108) | |||

| CEO_age | 0.00302 ** | 0.00293 ** | 0.00285 ** |

| (0.00136) | (0.00135) | (0.00135) | |

| CEO_gender | −0.06341 * | −0.07107 ** | −0.06897 * |

| (0.03575) | (0.03533) | (0.03537) | |

| TobinsQ | 0.00921 ** | 0.01000 *** | 0.00877 ** |

| (0.00361) | (0.00360) | (0.00360) | |

| Leverage | −0.00003 | −0.00003 | −0.00003 |

| (0.00024) | (0.00024) | (0.00024) | |

| ROE | 0.00005 ** | 0.00005 ** | 0.00005 ** |

| (0.00002) | (0.00002) | (0.00002) | |

| ROA | 0.00121 ** | 0.00120** | 0.00118 ** |

| (0.00060) | (0.00060) | (0.00059) | |

| Indirratio | 0.33347 *** | 0.28583 ** | 0.28128 ** |

| (0.09647) | (0.09621) | (0.09608) | |

| Duality | −0.04715 ** | −0.05097 ** | −0.05116 ** |

| (0.02289) | (0.02262) | (0.02265) | |

| Listing_tenure | −0.01926 *** | −0.01835 *** | −0.01882 *** |

| (0.00137) | (0.00136) | (0.00136) | |

| Industry Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 16,205 | 16,205 | 16,205 |

| R2 | 0.44756 | 0.45226 | 0.45347 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.44671 | 0.45138 | 0.45252 |

| ESG Rating | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| CEO_compensation | 0.01969 *** | −0.04123 | |

| (0.00412) | (0.02597) | ||

| CEO_age | 0.00302 ** | 0.00283 ** | 0.00133 |

| (0.00136) | (0.00136) | (0.00149) | |

| CEO_gender | −0.06341 * | −0.06400 * | −0.02966 |

| (0.03575) | (0.03564) | (0.04065) | |

| CEO_compensation x CEO_age | 0.00129 ** | ||

| (0.00052) | |||

| CEO_compensation x CEO_gender | −0.02766 * | ||

| (0.01565) | |||

| lnTA | 0.14518 *** | 0.13655 *** | 0.13631 *** |

| (0.00810) | (0.00828) | (0.00828) | |

| SOE | 0.04641 * | 0.04918 ** | 0.04810 * |

| (0.02508) | (0.02501) | (0.02501) | |

| TobinsQ | 0.00921 ** | 0.00829 ** | 0.00837 ** |

| (0.00361) | (0.00361) | (0.00361) | |

| Leverage | −0.00003 | −0.00002 | −0.00002 |

| (0.00024) | (0.00024) | (0.00024) | |

| ROE | 0.00005 ** | 0.00005 ** | 0.00005 ** |

| (0.00002) | (0.00002) | (0.00002) | |

| ROA | 0.00121 ** | 0.00102 * | 0.00103 * |

| (0.00060) | (0.00060) | (0.00060) | |

| Indirratio | 0.32271 *** | 0.33472 *** | 0.33440 *** |

| (0.09634) | (0.09640) | (0.09639) | |

| Duality | −0.04715 ** | −0.04757 ** | −0.04839 ** |

| (0.02289) | (0.02282) | (0.02282) | |

| Listing_tenure | −0.01926 *** | −0.01909 *** | −0.01912 *** |

| (0.00137) | (0.00136) | (0.00136) | |

| Industry Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 16,205 | 16,205 | 16,205 |

| R2 | 0.44756 | 0.44882 | 0.44912 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.44671 | 0.44793 | 0.44817 |

| ESG Rating | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| L.DT_freq | 0.05822 *** | 0.05118 *** | |

| (0.00609) | (0.00674) | ||

| CEO_compensation | 0.00042 | ||

| (0.00926) | |||

| L.DT_freq x CEO_compensation | 0.00531 ** | ||

| (0.00240) | |||

| CEO_age | 0.00255 * | 0.00293 ** | 0.00276 ** |

| (0.00138) | (0.00135) | (0.00134) | |

| CEO_gender | −0.06113 * | −0.07107 ** | −0.07048 ** |

| (0.03633) | (0.03533) | (0.03524) | |

| lnTA | 0.12146 *** | 0.13419 *** | 0.12627 *** |

| (0.00803) | (0.00810) | (0.00828) | |

| SOE | −0.07082 *** | 0.05383 ** | 0.05551 ** |

| (0.02406) | (0.02479) | (0.02473) | |

| TobinsQ | 0.01142 *** | 0.01000 *** | 0.00929 *** |

| (0.00363) | (0.00360) | (0.00360) | |

| Leverage | −0.00002 | −0.00003 | −0.00003 |

| (0.00025) | (0.00024) | (0.00024) | |

| ROE | 0.00006 ** | 0.00005 ** | 0.00005 ** |

| (0.00002) | (0.00002) | (0.00002) | |

| ROA | 0.00192 *** | 0.00120 ** | 0.00104 * |

| (0.00060) | (0.00060) | (0.00060) | |

| Indirratio | 0.33162 *** | 0.31721 *** | (0.09614) |

| (0.09706) | (0.09621) | (0.09706) | |

| Duality | −0.00672 | −0.05097 ** | −0.05149 ** |

| (0.02308) | (0.02262) | (0.02256) | |

| Listing_tenure | −0.01837 *** | −0.01835 *** | −0.01824 *** |

| (0.00136) | (0.00136) | (0.00135) | |

| Industry Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 16,205 | 16,205 | 16,205 |

| R2 | 0.43866 | 0.45226 | 0.45349 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.43783 | 0.45138 | 0.45254 |

| ESG Ratings | |

|---|---|

| DT_freq | 0.68889 *** |

| (0.13048) | |

| lnTA | 0.01437 |

| (0.02383) | |

| SOE | 0.13884 *** |

| (0.02415) | |

| CEO_age | 0.00150 |

| (0.00112) | |

| CEO_gender | −0.14989 *** |

| (0.03373) | |

| TobinsQ | 0.03247 *** |

| (0.00489) | |

| Leverage | 0.00026 |

| (0.00045) | |

| ROE | 0.00005 |

| (0.00005) | |

| ROA | 0.00726 *** |

| (0.00097) | |

| Indirratio | −0.03182 |

| (0.14453) | |

| Duality | −0.09383 *** |

| (0.01961) | |

| Listing_tenure | −0.00659 *** |

| (0.00246) | |

| Industry Fixed Effect | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes |

| Obs | 16205 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, C.; Kushinsky, D.; Ren, T. Digital Transformation, CEO Compensation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094033

Nie C, Kushinsky D, Ren T. Digital Transformation, CEO Compensation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094033

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Caiming, Dor Kushinsky, and Ting Ren. 2025. "Digital Transformation, CEO Compensation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094033

APA StyleNie, C., Kushinsky, D., & Ren, T. (2025). Digital Transformation, CEO Compensation, and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability, 17(9), 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094033