Does the Underlying Design of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Indices Affect Investor Reactions? The Role of Legitimacy and Reputation Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. ESG Indices and Investor Reactions

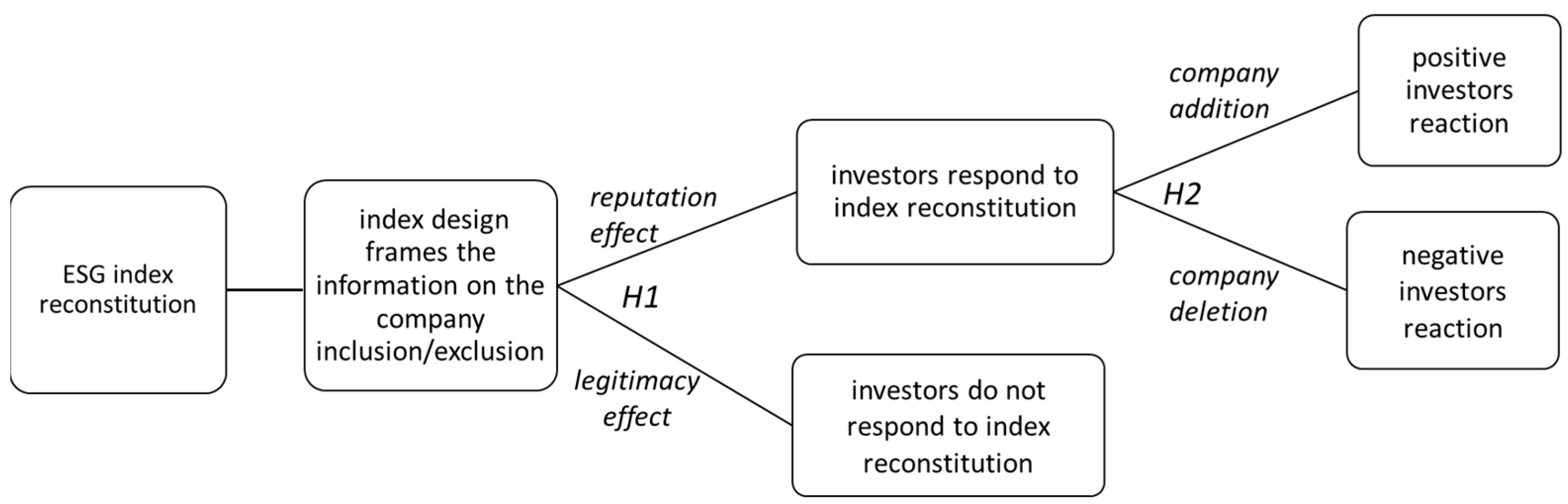

2.2. Legitimacy and Reputation Effects of ESG Index Design

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social and Governance |

| U.S. | United States of America |

| SRI | socially responsible investing |

| CSR | corporate social responsibility |

| CFP | corporate financial performance |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| DJSI | Dow Jones Sustainability Index |

| CAAR | cumulative average abnormal return |

| CAPM | Capital Assets Pricing Model |

| DJIA | Dow Jones Industrial Average |

| MM | market model |

References

- Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. The Global Sustainable Investment Review 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.gsi-alliance.org/members-resources/gsir2022/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Lackmann, J.; Ernstberger, J.; Stich, M. Market Reactions to Increased Reliability of Sustainability Information. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirigoyen, G.; Poulain-Rehm, T. Relationships between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: What is the causality? J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 4, 18–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.W.K. Do Stock Investors Value Corporate Sustainability? Evidence from an Event Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolandi, C.; Jaiswal-Dale, A.; Poggiani, E.; Vercelli, A. Global Standards and Ethical Stock Indexes: The Case of the Dow Jones Sustainability Stoxx Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Lee, C.W. Performance of stock price with changes in SRI governance index. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchander, S.; Schwebach, R.G.; Staking, K. The informational relevance of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from DS400 index reconstitutions. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.W.K.; Roca, E. The effect on price, liquidity and risk when stocks are added to and deleted from a sustainability index: Evidence from the Asia Pacific context. J. Asian Econ. 2013, 24, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Soni, P. Does the stock market react to the sustainability index reconstitutions? Evidence from the S&P BSE 100 ESG index. South Asian J. of Bus. Stud. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Howton, S.D.; Siegel, D. Does the Market Respond to an Endorsement of Social Responsibility? The Role of Institutions, Information, and Legitimacy. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1461–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappou, K.; Oikonomou, I. Is There a Gold Social Seal? The Financial Effects of Additions to and Deletions from Social Stock Indices. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Pandey, V.; Ross, R.B. Asymmetry in Stock Market Reactions to Changes in Membership of the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Inq. 2017, 16, 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rudkin, W.; Cai, C.X. Information content of sustainability index recomposition: A synthetic portfolio approach. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 88, 102676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, R.; Paugam, L.; Stolowy, H. Do investors actually value sustainability indices? Replication, development, and new evidence on CSR visibility. Strat. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1474–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O.; Chatterji, A.K.; Mitchell, W. Do investors actually value sustainability? New evidence from investor reactions to the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI). Strat. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 949–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.K.; Aksoy, M.; Tatoglu, E. Does the stock market value inclusion in a sustainability index? Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Sustainability 2020, 12, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipeta, C.; Gladysek, O. The impact of Socially Responsible Investment Index constituent announcements on firm price: Evidence from the JSE. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2012, 15, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Takeuchi, K. Sustainability membership and stockprice: An empirical study using the Morningstar-SRI Index. App. Financ. Econ. 2013, 23, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Dąbrowski, T.J. Investor Reactions to Sustainability Index Reconstitutions: Analysis in Different Institutional Contexts. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O.; Chatterji, A.; Mitchell, W. How Firm Performance Moderates the Effect of Changes in Status on Investor Perceptions: Additions and Deletions by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. 2014. Available online: https://sites.duke.edu/ronniechatterji/files/2014/04/DJSI-OS-Final.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Zou, P.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhou, C. Does doing good lead to doing better in emerging markets? Stock market responses to the SRI index, announcements in Brazil, China, and South Africa. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2020, 48, 966–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Dąbrowski, T.J. The Role of Stock Exchanges in the Transmission of Sustainable Development Goals to Enterprises: The Case of Brasil, Bolsa, Balcão. In Economics of Sustainable Transformation; Szelągowska, A., Pluta-Zaręba, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.J.; Hope, C. A critical review of sustainable business indices and their impact. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational Legitimacy Social Values and Organizational Behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.G.; Whetten, D.A. Rethinking the Relationship Between Reputation and Legitimacy: A Social Actor Conceptualization. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Bitektine, A.; Haack, P. Legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 451–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.; Lee, P.M.; Dai, Y. Organizational reputation: A review. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellyn, P.G. Corporate reputation: Focusing the Zeitgeist. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, K.; Camerer, C. Reputation and Corporate Strategy: A Review of Recent Theory and Applications. Strat. Manag. J. 1988, 9, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. A Framework Linking Intangible Resources and Capabilities to Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Strat. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S.; Wensley, R. Assessing Advantage A Framework for Diagnosing Competitive Superiority. J. Market. 1988, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.; Kleffner, A.; Bertels, S. Signalling Sustainability Leadership: Empirical Evidence of the Value of DJSI Membership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeds, D.L.; Mang, P.Y.; Frandsen, M.L. The Influence of Firms’ and Industries’ Legitimacy on the Flow of Capital into High-Technology Ventures. Strat. Org. 2004, 2, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P.; Sever, J.M. Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.; Guffey, H.G.; Kijewski, V. The effects of information and company reputation on intentions to buy a business service. J. Bus. Res. 1993, 27, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M. The social construction perspective on ESG issues in SRI indices. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2013, 3, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windolph, S.E. Assessing corporate sustainability through ratings: Challenges and their causes. J. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, K.; Rani, E. A bibliometric analysis of ESG literature: Key themes, influential authors and future research directions. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekelenburg, A.; Georgakopoulos, G.; Sotiropoulou, V.; Vasileiou, K.; Vlachos, I. The relation between sustainability performance and stock market returns: An empirical analysis of the Dow Jones Sustainability Index Europe. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 7, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyglidopoulos, S.C. The issue life-cycle: Implications for reputation for social performance and organizational legitimacy. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitektine, A. Toward a Theory of Social Judgments of Organizations: The Case of Legitimacy, Reputation, and Status. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Fiol, C.M. Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppell, J.G.S. Global governance organizations: Legitimacy and authority in conflict. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D.; Armengou, J. Moral legitimacy in controversial projects and its relationship with social license to operate: A case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L. To be different, or to be the same? It’s a question (and theory) of strategic balance. Strat. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Walter, P. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Jermier, J.M.; Lafferty, B.A. Corporate Reputation: The Definitional Landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbig, P.; Milewicz, J. To be or not to be … credible that is: A model of reputation and credibility among competing firms. Market. Intell. Plan. 1995, 13, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basdeo, D.K.; Smith, K.G.; Grimm, C.M.; Rindova, V.P.; Derfus, P.J. The impact of market actions on firm reputation. Strat. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Cable, D.M. Firm reputation and applicant pool characteristics. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Rindova, V. Who’s Tops and Who Decides? The Social Construction of Corporate Reputations; Working Paper; New York University, Stern School of Business: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, A.M. Market Signaling: Informational Transfer in Hiring and Related Screening Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Markwick, N.; Fill, C. Towards a framework for managing corporate identity. Eur. J. Market. 1997, 31, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.; Waddock, S. Corporate Responsibility and Financial Performance: The role of Intangible Resources. Strat. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.; Castellano, S. The impact of globalization on legitimacy signals: The case of organizations in transition environments. Balt. J. Manag. 2011, 6, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FTSE Russel. FTSE4Good Index Series 2019. Available online: https://research.ftserussell.com/products/downloads/FTSE4Good_Index_Series.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- S&P Dow Jones Indices; RobecoSAM. Dow Jones Sustainability Indices Methodology. 2019.

- Carmeli, A.; Tishler, A. Perceived Organizational Reputation and Organizational Performance: An Empirical Investigation of Industrial Enterprises. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2005, 8, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.H. Investment Bank Reputation and the Price and Quality of Underwriting Services. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 2729–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obłój, T.; Obłój, K. Diminishing Returns from Reputation: Do Followers Have a Competitive Advantage? Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C. Perceptions of Price Unfairness: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Market. Res. 1999, 36, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar García de los Salmones, M.; Pérez, A. Effectiveness of CSR advertising: The role of reputation, consumer attributions, and emotions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.E.; Hartwick, J. The Effects of Advertiser Reputation and Extremity of Advertiser Claims on Advertising Effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburry, W. Reputation and supportive behavior: Moderating impacts of foreignness, industry and local exposure. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Protecting Organization Reputations During a Crisis: The Development and Application of Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J. Corporate reputation: A free-market solution to unethical behaviour. Bus. Soc. 1989, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnietz, K.E.; Epstein, M.J. Exploring the Financial Value of Reputation for Corporate Responsibility During a Crisis. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2005, 7, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Unpacking the halo effect: Reputation and crisis management. J. Commun. Manag. 2006, 10, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D. Narrative, politics and legitimacy in an IT implementation. J. Manag. Stud. 1998, 35, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Dąbrowski, T.J.; Gad, J.; Tomaszewski, J. Is Reputation for Corporate Social Responsibility a Double-Edged Sword? Lessons from Investor Reactions on Foreign Companies Activity in Russia During the Invasion of Ukraine. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierickx, I.; Cool, K. Asset Stock Accumulation and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertels, S.; Peloza, J. Running Just to Stand Still? Managing CSR Reputation in an Era of Ratcheting Expectations. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, J.A.; Li, M. Asymmetric asset price reaction to news and arbitrage risk. Rev. Behav. Financ. 2009, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Han, S.H. Stock Market Reaction to Corporate Crime: Evidence from South Korea. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasesh, R.V. Baldrige Award announcement and shareholder wealth. Int. J. Qual. Sci. 1998, 3, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.; Svetina, M. Does local news matter to investors? Manag. Financ. 2011, 37, 1190–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, F.L.; Bongbee, N.S. Event Study on the Reaction of Stock Returns to Acquisition News. Int. Financ. Bank. 2017, 4, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Fisher, L.; Jensen, M.C.; Roll, R.W. The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information. Int. Econ. Rev. 1969, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.G.; de Vega, M.E.M. Corporate reputation and firms’ performance: Evidence from Spain. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1231–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Kanuri, V.K. Investor reactions to concurrent positive and negative stakeholder news. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeszczyński, J.; Gajdka, J.; Schabek, T. Investment performance of component stocks from the Respect Sustainability Index at the Warsaw Stock Exchange. In Proceedings of the 31st Australasian Finance and Banking Conference 2018, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.M.; Moran, D. Impact of the FTSE4Good Index on firm price: An event study. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 82, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberndorfer, U.; Schmidt, P.; Wagner, M.; Ziegler, A. Does the stock market value the inclusion in a sustainability stock index? An event study analysis for German firms. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2013, 66, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.P.; Lo, L.Y.; Huang, W.C. Market Reactions to Firms’ Inclusion in the Sustainability Index: Further Evidence of TCFD Framework Adoption. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 40, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Event Studies in Management Research: Theoretical and Empirical Issues. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 626–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinlay, A.C. Event studies in economics and finance. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The capital asset pricing model: Theory and evidence. J. Econ. Perspect. 2004, 18, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Dąbrowski, T.J. Do Investors Appreciate Information about Corporate Social Responsibility? Evidence from the Polish Equity Market. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder’s value. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luffarelli, J.; Awaysheh, A. The impact of indirect corporate social performance signals on firm value: Evidence from an event study. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewatsch, S.; Kleindienst, I. When Does It Pay to be Good? Moderators and Mediators in the Corporate Sustainability–Corporate Financial Performance Relationship: A Critical Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 383–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Sabaté, J.M.; de Quevedo-Puente, E. Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Corporate Reputation and Financial Performance: A Survey of the Literature. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2003, 6, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, V.S.; Gardberg, N.A.; Rahman, N. Corporate Reputation’s Invisible Hand: Bribery, Rational Choice, and Market Penalties. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slager, R.; Gond, J.P. The politics of reactivity: Ambivalence in corporate responses to corporate social responsibility ratings. Organ. Stud. 2022, 43, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Perspective | Differentiating Factor | Legitimacy | Reputation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legitimacy and reputation as an evaluation | Point of reference (context) | Norms, values, ethics (contribution to the common good) | Other organizations and their performance |

| Type of evaluation | Absolute | Relative | |

| Stratification | Does not lead to a hierarchy | Place in the hierarchy is decisive | |

| Key mechanism | Conformism | Competition | |

| Legitimacy and reputation as a resource | Features of the resource | Valuable, imperfectly imitable, and not readily substitutable, but not rare | Valuable, imperfectly imitable, not readily substitutable, and rare |

| Ability to confer a competitive advantage | Does not confer a competitive advantage | Confers a competitive advantage | |

| Market effect (strategic consequences) | Leads to homogenization | Enables differentiation |

| Index Type | ESG Index Used in Our Research | Effects Generated by Indices |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A | ||

| Indices based on a negative screening | FTSE4Good US Index | Legitimacy effect |

| Companies from sectors considered as not contributing to the common good and/or those that violate current social norms and values are excluded a priori. | Companies manufacturing tobacco, weapons, and coal are excluded from the index a priori, as they are companies identified as being embroiled in significant controversy. | Contributing to the common good and behaving consistently with socially acceptable values and norms boosts moral legitimacy. |

| The selection mechanism is based on the results of absolute evaluation of companies in terms of ESG criteria; ratings obtained by other companies are irrelevant. | The ESG rating level required of each included company is 3.3 or more; companies’ scores are not cross-compared. | As companies are not benchmarked against each other, the design of such indices does not give rise to a hierarchy. |

| The selection mechanism is not based on competition between companies—all candidates exceeding a certain threshold are included. | All companies that pass the eligibility criteria are automatically included in the index; the number of constituents is not limited—additional inclusions pose no threat to companies already in the index; exclusions occur only when a company engages in restricted activities, becomes the subject of significant controversy, or its ESG assessment results decline below the threshold. | The lack of a competition mechanism promotes mimetic processes. |

| Panel B | ||

| Indices following a best-in-class approach | DJSI North America Index | Reputation effect |

| Companies are not excluded a priori on account of the profile of their business. | The universe of companies under consideration consists of the largest 600 US and Canadian companies included in the S&P Global BMI, and therefore also includes entities operating in controversial sectors. | Neither norms nor values are a reference point for pre-selection. |

| The selection mechanism is based on the cross-comparison of companies’ scores within their respective sectors, and so it is relative in nature. | The Total Sustainability Score is calculated for each company under an annual Corporate Sustainability Assessment; this score is the basis for ranking companies within their sectors. Therefore, a company’s position in the hierarchy depends not only on the results of its evaluation, but also on the scores of other companies in the sector. | Comparing assessment results makes evaluation relative and gives rise to a hierarchy. |

| At the core of the selection mechanism is competition, as only the top scorers within their respective sectors are included in the index. | Only 20% of companies with the highest ratings within a sector are included in the index; at the next revision of index composition, a company maintaining the same score, which previously secured it a place in the index, may be excluded from it if its competitors’ assessments have improved. | The selection mechanism is based on competition driven by constant rivalry for a position within the hierarchy. |

| Index | Number of Index Reconstitutions | Total Number of Events a | Number of Ineligible Events b | Number of Outliers | Percentage of Rejected Events | Number of Eligible Events | Number of Company Additions | Number of Company Deletions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTSE4Good US | 31 | 357 | 15 | 2 | 5% | 340 | 242 | 98 |

| DJSI North America | 11 | 387 | 35 | 1 | 9% | 351 | 199 | 152 |

| Total | 42 | 744 | 50 | 3 | 7% | 691 | 441 | 250 |

| FTSE4Good US Index | DJSI North America Index |

|---|---|

| n1 = 242 (added companies) | n1 = 199 (added companies) |

| n2 = 98 (deleted companies) | n2 = 152 (deleted companies) |

| Levene’s F = 19.998 *** | Levene’s F = 0.094 |

| t = −1.464 | t = 2.154 ** |

| Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.490 | Mann–Whitney’s U = −1.945 * |

| Added Companies (n = 199) | Deleted Companies (n = 152) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAR | t-Test | z-Test | Standard Deviation | CAAR | t-Test | z-Test | Standard Deviation |

| 0.32 | 1.712 ** | 1.914 ** | 2.618 | −0.28 | −1.372 * | −1.298 * | 2.474 |

| FTSE4Good US Index | DJSI North America Index | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Modification | n1 = 242 (Added Companies) n2 = 98 (Deleted Companies) | n1 = 199 (Added Companies) n2 = 152 (Deleted Companies) |

| MM | Levene’s F = 20.225 *** t = −1.415 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.713 | Levene’s F = 0.217 t = 1.874 * Mann–Whitney’s U = −1.456 |

| DJIA | Levene’s F = 17.282 *** t = −1.365 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.535 | Levene’s F = 0.197 t = 2.494 ** Mann–Whitney’s U = −2.452 ** |

| Beta | Levene’s F = 16.954 *** t = −1.483 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.538 | Levene’s F =0.180 t = 2.085 ** Mann–Whitney’s U = −1.812 * |

| Event window | ||

| <−1; +1> | Levene’s F = 17.335 *** t = −1.247 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.705 | Levene’s F = 0.043 t = 0.712 Mann–Whitney’s U = −0.351 |

| <−1; +2> | Levene’s F = 26.458 *** t = −1.350 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.228 | Levene’s F = 0.048 t = 1.272 Mann–Whitney’s U = −1.039 |

| <−1; +4> | Levene’s F = 20.444 *** t = −1.389 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.491 | Levene’s F = 0.191 t = 1.775 ** Mann–Whitney’s U = −1.417 |

| <−1; +5> | Levene’s F = 30.699 *** t = −1.125 Mann–Whitney’s U = 0.503 | Levene’s F = 0.000 t = 1.875 ** Mann–Whitney’s U = −1.494 |

| Added Companies (n = 199) | Deleted Companies (n = 152) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Modification | CAAR | t-Test | z-Test | Standard Deviation | CAAR | t-Test | z-Test | Standard Deviation |

| MM | 0.36 | 1.828 ** | 0.496 | 2.772 | −0.18 | −0.879 | −1.298 * | 2.575 |

| DJIA | 0.39 | 2.092 ** | 1.772 ** | 2.623 | −0.30 | −1.487 * | −0.3244 | 2.520 |

| Beta | 0.30 | 1.606 * | 0.922 | 2.632 | −0.27 | −1.377 * | −1.460 * | 2.478 |

| Event window | ||||||||

| <−1; +1> | 0.06 | 0.373 | 0.496 | 2.184 | −0.11 | −0.622 | −0.162 | 2.167 |

| <−1; +2> | 0.17 | 1.025 | 0.922 | 2.405 | −0.16 | −0.792 | −0.162 | 2.484 |

| <−1; +4> | 0.24 | 1.125 | 1.489 * | 3.069 | −0.33 | −1.388 * | −0.487 | 2.954 |

| <−1; +5> | 0.26 | 1.105 | 0.780 | 3.331 | −0.42 | −1.512 * | −1.136 | 3.425 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamska, A.; Dąbrowski, T.J. Does the Underlying Design of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Indices Affect Investor Reactions? The Role of Legitimacy and Reputation Effects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094031

Adamska A, Dąbrowski TJ. Does the Underlying Design of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Indices Affect Investor Reactions? The Role of Legitimacy and Reputation Effects. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094031

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamska, Agata, and Tomasz J. Dąbrowski. 2025. "Does the Underlying Design of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Indices Affect Investor Reactions? The Role of Legitimacy and Reputation Effects" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094031

APA StyleAdamska, A., & Dąbrowski, T. J. (2025). Does the Underlying Design of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Indices Affect Investor Reactions? The Role of Legitimacy and Reputation Effects. Sustainability, 17(9), 4031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094031