1. Introduction

In the context of accelerated urbanization and growing population pressures, urban policies, which are intricately linked to governance implementation, play a crucial role in promoting ecological balance and maintaining urban environmental quality [

1]. Cities are facing increasingly severe environmental, social, and economic challenges, which call for a re-examination of traditional urban development models. In this process, concepts, such as resilient cities, environmental planning, inclusive governance, and governance modernization have emerged, reflecting the latest trends in urban governance [

2,

3,

4]. These concepts also highlight the deep concern of governance actors regarding urban sustainability, adaptability, and equity. The core of these concepts points to a key issue—how the trend of integrating urban space governance with the triad of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) is evolving towards a more humanized direction. The sustainable development of cities not only relies on the effective use of resources and environmental protection but also requires a sound, transparent, and participatory governance system. This governance system emphasizes the need to promote the coordinated development of cities in environmental, social, and economic dimensions through scientifically rational environmental planning, effective policy implementation, and active community involvement [

5]. This, in turn, fosters the optimization of urban space, improves the quality of life for residents, and ensures the sustainable use of natural resources and effective management of environmental risks. However, as urbanization progresses, the challenges of urban environmental governance are becoming increasingly complex [

6]. Particularly in certain urban areas, street vendors have become a significant issue affecting urban governance and residents’ quality of life.

The management of street vendors exemplifies a critical micro-scale issue in urban environmental governance, involving the allocation and regulation of public spaces, such as vending streets and plazas [

7]. Such practices reflect the balance that urban environmental governance seeks to achieve between social equity and economic vibrancy [

8,

9]. The space occupation of street vendors has long been a concern for city managers and planners. Being part of the “microeconomy” of cities and a representative group within the informal economy sector, street vendors make significant contributions to employment promotion, poverty alleviation, and economic vitality [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, their presence also presents various risks and challenges in the urban space, such as traffic congestion, environmental sanitation issues, and public health concerns [

15,

16,

17]. These factors to some extent undermine the sense of order and safety in cities, making the governance of urban vending zones a complex decision-making process for urban managers [

18,

19].

Globally, approaches to managing street vendors in terms of urban space can be broadly categorized into two models: spatial exclusion and spatial inclusion [

20]. Each implies distinct strategies and policy philosophies for managing street vendors, reflecting varied stances on the issue across different countries. Environmental governance for spatial exclusion often relies on legislation, enforcement, and administrative measures to manage street vendor activities in public spaces [

21]. In some countries, such as South Africa, restrictive measures, like forced evictions, are used, while in Kolkata, local authorities balance enforcement with recognition of vendors’ economic contributions [

22,

23]. In comparison, China’s evolving governance strategies are increasingly focusing on inclusivity and collaboration, demonstrating a more adaptive approach to managing urban environment. Although the governance of spatial exclusion can effectively safeguard urban aesthetics and public order, it can also have negative impacts [

21,

22]. Such restrictive policies may increase survival pressure on low-income vendors, compelling them to move frequently and even placing them in conflict with enforcement officials [

23,

24].

In contrast, environmental governance in the spatial inclusion model adopts a more tolerant approach. By setting up designated and regulated zones for vendors to use with lenient policies, it encourages street vendors to operate in specific areas or during certain times [

25]. It aims to balance urban aesthetics with the needs of vendors and their customers, which improves urban land use and fosters a relatively harmonious public space [

26]. For instance, in Singapore, municipal authorities control street vending, with permission required to operate in vending zones and daily patrols to maintain cleanliness and order in public spaces [

27]. In London, the boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea regulate street trading on Portobello and Golborne Road through the London Local Authorities Act [

28]. Malaysian local governments adopt a tolerant approach toward vendors, recognizing their cultural significance and economic importance while issuing permits to formalize their operations [

29]. In Houston, USA, local authorities support street vending through improvement districts [

14]. Meanwhile, Indian local governments mandate that urban planning must be inclusive, reserving urban land and space for street vendors [

12]. The use of blockchain technology to provide an efficient, transparent, and secure management system has even been attempted [

30]. Governance for spatial inclusion has demonstrated effectiveness in balancing urban order with economic vibrancy, providing both convenience for citizens and stable operations for vendors. However, this approach also highlighted opportunities for improvement, such as enhancing infrastructure, simplifying licensing processes, and refining management systems to ensure smoother day-to-day operations [

31,

32,

33].

In recent years, China has been gradually transitioning its model of urban environmental governance for street vendors towards spatial inclusion. Scholars have compared the vending governance in Chinese cities like Suzhou, Jiaxing and Taicang. Their studies reveal that larger cities, like Suzhou, tend to integrate vending governance with tourism development, while smaller cities, like Taicang, focus more on community engagement and flexible strategies to balance urban cleanliness and vendor livelihoods [

34]. The governance model in Nanjing has similarly evolved from overt confrontation to implicit cooperation [

35]. This suggests that China is moving towards a model of environmental governance that combines flexible management with humanization, reflecting a policy orientation of inclusiveness and collaborative participation [

36]. Recch describes the transformation of China’s street vending governance as a “calm” shift: although it may appear smooth on the surface, it involves complex governance and policy adjustments behind the scenes [

37]. Despite this transition, governance effectiveness remains limited by high administrative costs and low efficiency. Research shows that the awareness of self-management among vendors is still weak, making effective self-regulation and governance participation difficult to achieve [

37]. As a result, while urban management departments make significant investments, vending activities often fall short of expectations [

36,

38,

39]. The governance of urban environment for street vendors still relies heavily on frequent administrative intervention [

39].

Against this background, this research examines the specific case of the Waliu Community, the first community in Zhengzhou and also one of the earliest communities in China to apply the self-management model of urban environment for street vendors, exemplifying emerging trends in China. Known for its high concentration of street vendors, the environmental governance in Waliu Community has transitioned successively through three models: spatial exclusion, spatial inclusion, and spatial self-management. By reviewing the three-year governance journey of street vendors in this community, this paper elaborates on how vendors occupied urban spaces at different stages and how local authorities adapted and refined their strategies of vending zone governance. A comprehensive analysis of these models sheds light on their social impacts throughout this period. Following

Section 2, which introduces the research methods,

Section 3 details the main measures and outcomes for the governance models of spatial exclusion and spatial inclusion.

Section 4 delves into the final model of spatial self-management, introducing the limited self-management of urban space use for street vendors, a relatively sustainable approach.

Section 5 provides an evaluation of environmental governance transformation based on four key indicators. Finally, this paper discusses the social benefits and potential risks of this transformation.

2. Methodology

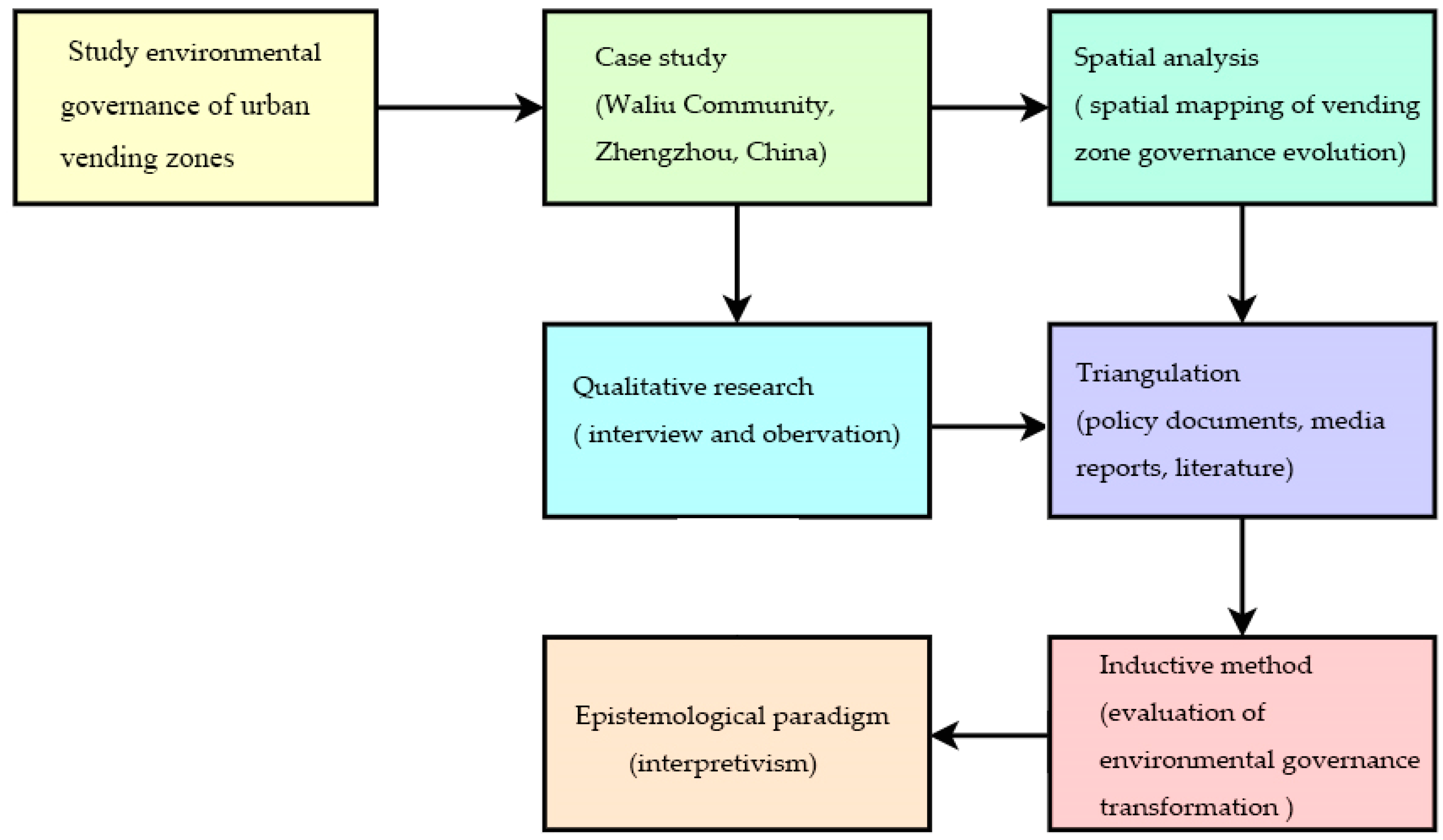

This research utilizes a mixed-methods approach that combines spatial analysis, direct observation, semi-structured interviews, and questionnaires to examine how street vendors use urban land and interact with residents within the governance frameworks of the Waliu Community in Zhengzhou. The multi-source data were collated to explain the complex relationship between vendors and the urban spaces they occupy. Each method was designed to complement the others, providing a holistic view of vendor activity and vending zone governance.

The research scope encompasses the environmental governance transformation of vending zones in the Waliu Community, Zhengzhou, China. The key indicators to be investigated are as follows:

Spatial Utilization Efficiency: Measures how effectively urban space is utilized by street vendors and residents.

Vendor Livelihood: Assesses the impact of governance strategies on vendors’ economic well-being.

Social Order and Safety: Evaluates the impact on public order, safety, and community cohesion.

Stakeholder Satisfaction: Evaluates the perceived satisfaction of stakeholders (vendors, residents) with governance outcomes.

To evaluate these indicators at each stage of the case study (spatial exclusion, spatial inclusion, and spatial self-management), the following research methods are proposed.

Spatial mapping was used to visualize and quantify vendor distribution and space usage at the different stages of environmental governance [

40]. The research employed manual mapping techniques based on measurement, Auto CAD, Google Map, and observation, to illustrate spatial data, identify vendor concentration areas, and assess the spatial arrangements of designated vending zones. This method provides a detailed understanding of how vendor activities interact with surrounding environmental elements, such as sidewalks, intersections, and commercial zones [

41].

To obtain real-time insights into the daily operations and interactions of street vendors, this research employed direct observations and surveys to assess the impact on pedestrian flow, traffic congestion, and public space accessibility [

42]. Fieldwork was conducted from September 2023 to December 2024, documenting vendors’ day-to-day behaviours, position, spatial adaptation strategies, and responses to regulatory changes. Observations conducted by Yue Zhai focused on the interactions between vendors, customers, urban management personnel, and local residents. The positioning of vendor stalls (e.g., sidewalk vending and intersection clustering) in different stages was studied, as were the adaptative strategies employed to meet the spatial restrictions imposed by urban authorities. Data were collected by Yue Zhai using field notes, official records, photographs, and video recordings, providing a comprehensive view of vendor behaviours within the various governance settings.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key stakeholders, including street vendors, community residents, local government officials, and urban planners. They offer a deeper understanding of the power dynamics and regulatory frameworks of vending zone governance [

41]. The interviews were designed to explore perceptions of governance effectiveness and inclusivity of environmental governance. Interviews with vendors were designed to understand their economic conditions, business opportunities, and challenges. Interview data were transcribed and coded using thematic analysis. This facilitated the identification of recurring themes and patterns related to vendor self-management, regulatory flexibility, and stakeholder engagement [

43,

44]. Thirty in-depth interviews were conducted with key informants, encompassing three primary stakeholder groups: urban management officers, street vendors, and nearby residents.

This group consists of two frontline enforcement officers and two deputy section chiefs (who are also planners of the vending zones) from the Division of Urban Management and Comprehensive Law Enforcement. As the direct implementers of governance measures, their viewpoints are of crucial significance for understanding administrative rationales, enforcement logics, procedural executions, and daily operational challenges. Their insights help uncover the practical tensions inherent in the functioning of governance systems. Vendors from various sectors, such as fruits, snacks, and vegetables, were selected from multiple vendor guidance zones, considering variables like gender, age, and years of business experience. As the direct targets of governance interventions, their narratives offer crucial understandings of policy perception, institutional coping strategies, and spatial adaptation behaviours, thereby serving as key indicators for evaluating grassroots policy effectiveness. The residents interviewed, drawn from different vendor guidance zones, have long-term living experience in the area and possess stable and sustained observations of the impacts of street vending activities. Their perspectives not only reflect the public’s acceptance of urban space utilization but also provide a critical perspective on the fairness and responsiveness of current governance models. The detailed composition is as follows in

Table 1.

A total of 220 questionnaires were issued in this satisfaction survey, and 207 were effectively recovered, with a recovery rate of 94.1%. Among them, 110 questionnaires were issued to vendors and 91 were recovered; 110 questionnaires were issued to residents and 116 were recovered (

Table 2). The survey was measured by Likert five-level scale. The questionnaire sample consists of both vendors and residents, with a relatively balanced ratio that reflects the dual perspectives of governance providers and recipients. Vendor questionnaires focus on business characteristics, policy awareness, and feedback on governance practices, while resident questionnaires emphasize consumption behaviours, perceptions of public order, and satisfaction levels. This sample structure enables a comparative analysis across multiple stakeholder groups and facilitates logical inference based on diverse interests and experiences.

To enhance the validity and reliability of the research findings, the study employed data triangulation. Findings from spatial mapping, observations, and interviews are cross-referenced with policy documents, media reports, and the academic literature. This provides a comprehensive understanding of the socio-political dynamics of urban environmental governance. The triangulation method allows for a robust analysis of the way by which governance transformations influence land use, vendor behaviours, space operation, and social order. An illustration of the research methodology and instruments can be viewed in

Figure 1.

3. Waliu Community from Spatial Exclusion to Spatial Inclusion

3.1. Waliu Community and Spatial Exclusion

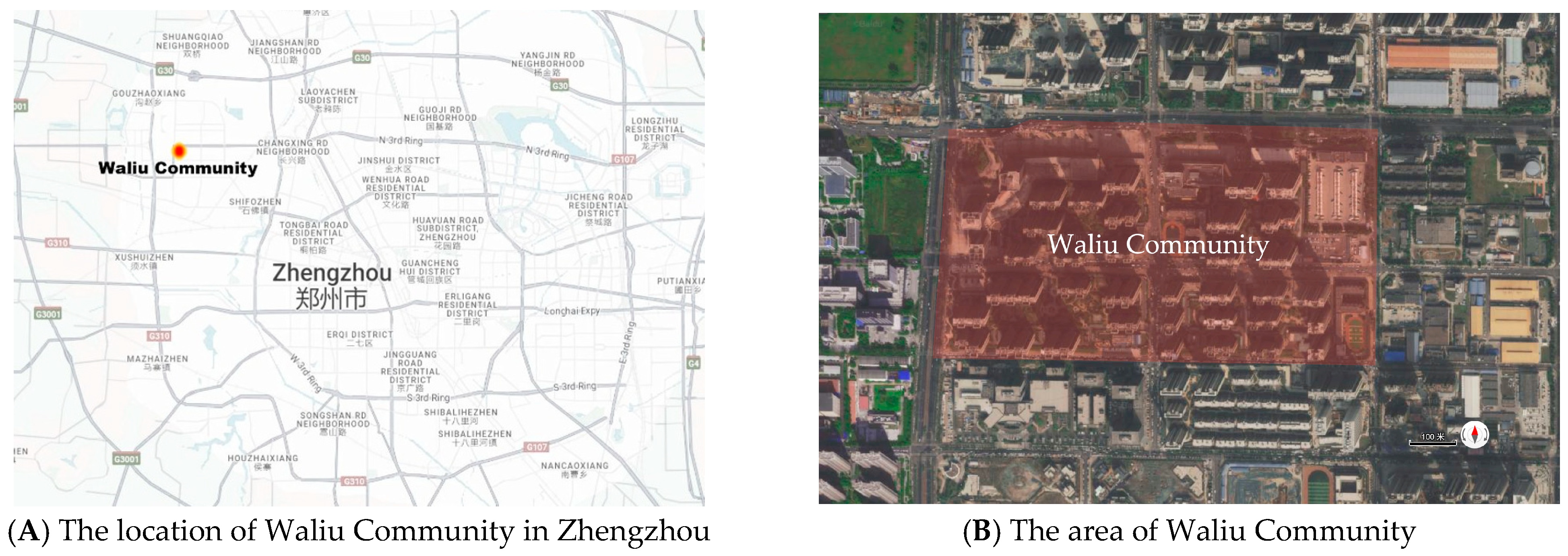

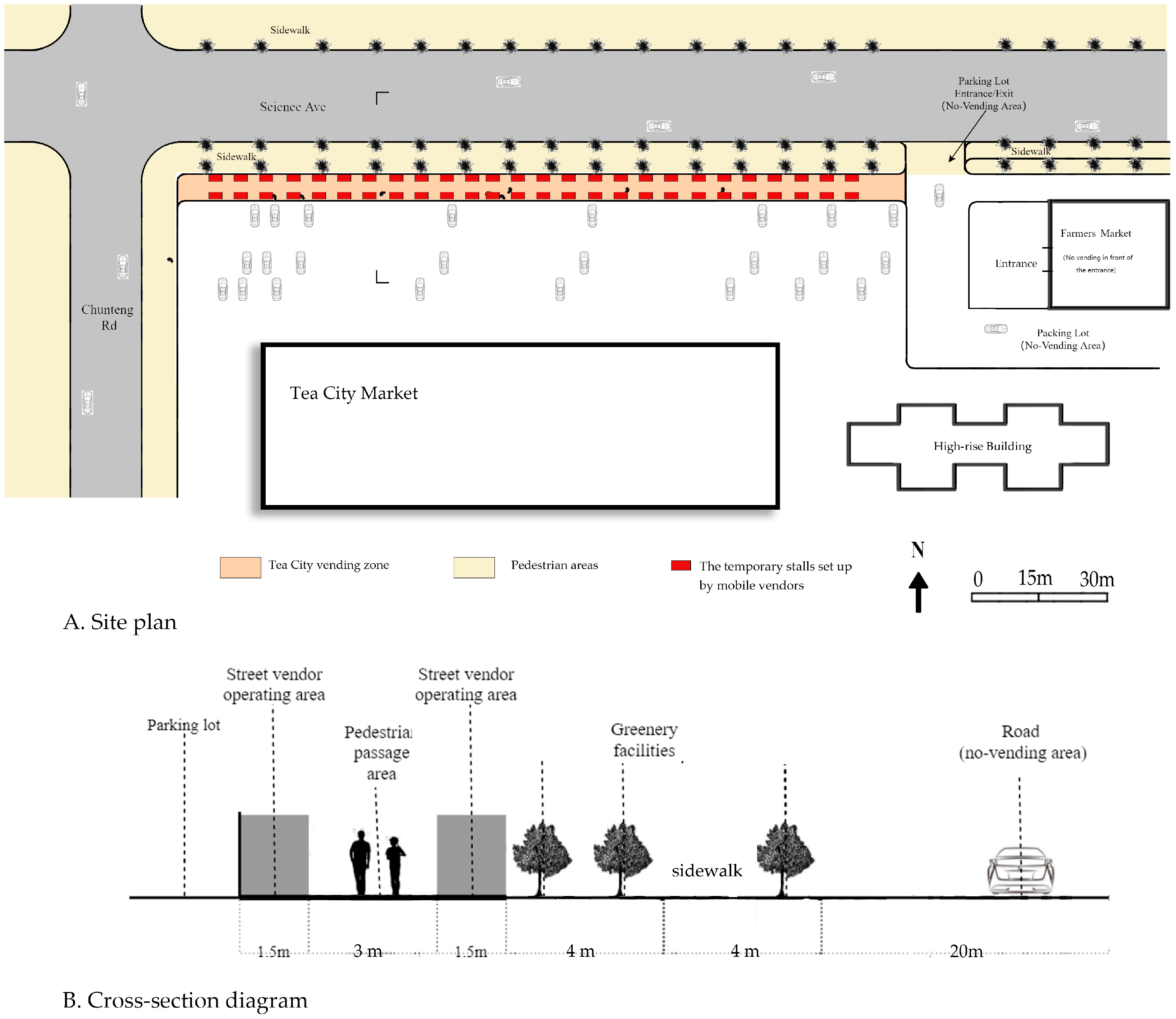

The early Waliu Community, located northwest of the city Zhengzhou, represents a case of environmental governance shifting from spatial exclusion to spatial inclusion. The community of four-square housing blocks consists of five residential areas with 13 buildings and a total population of approximately 8000 people (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). With its social and economic structure, the Waliu Community highlights the multi-layered issues arising during the urbanization process and the corresponding changes applied to management strategies. There are a significant number of migrant workers, low-income urban residents, and a small portion of local residents. Most of these residents lack the skills and knowledge required for stable employment and have strong family care obligations. As a result, economic activities within the community mainly contain low-barrier, quick-turnover, and highly mobile street vending operations. Due to the lack of allocated vending space, the influx of street vendors and the widespread practice of occupying roads for business were causing significant disruptions to traffic and disturbing the daily lives of residents.

Vending activities and the urban public environment in Waliu Community are managed by the Urban Management Department of the Wutong Subdistrict Office, one of the grassroots government bodies in the city of Zhengzhou. The urban management system in Zhengzhou is structured hierarchically: At the summit is the Zhengzhou Urban Management Bureau, followed by district-level urban management teams, and finally, the urban management departments of the various subdistrict offices. The Zhengzhou Urban Management Bureau is responsible for formulating policies and overseeing their implementation. District-level urban management teams provide direct guidance and supervision to the urban management departments of the subdistrict offices, each of which is directly responsible for managing vending activities and public land use within its own jurisdiction. Note that all references to “urban managers” below refer specifically to the Urban Management Department of the Wutong Subdistrict Office.

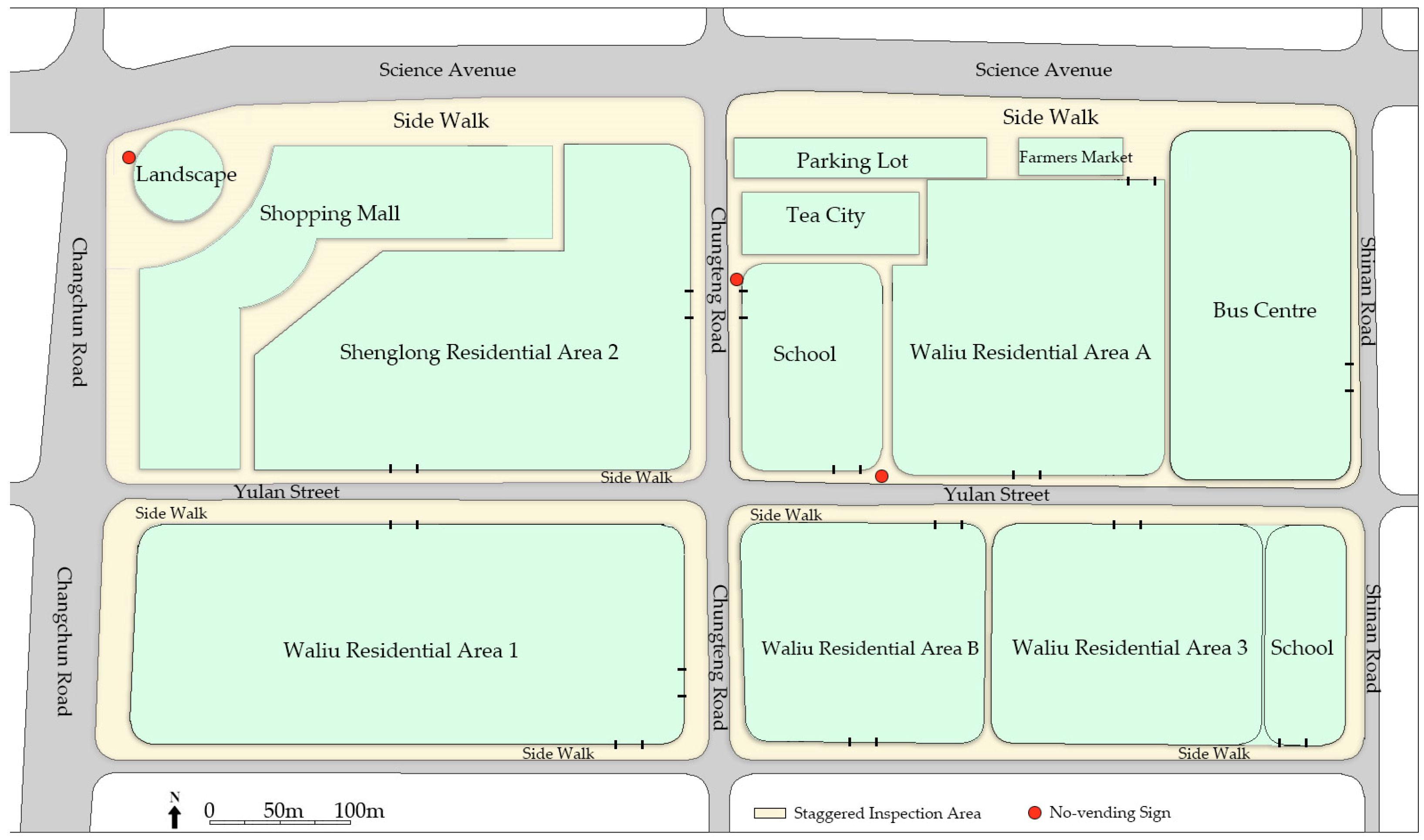

Over the spatial exclusion period, although street vending was strictly prohibited in the entire Waliu Community under the direct management of the Wutong Subdistrict Office. No specific vending space was planned for vendors to use. The urban managers implemented rigorous enforcement measures, including staggered inspections, the establishment of no-vending zones, and joint enforcement operations, to ensure that street vendors did not encroach upon primary urban spaces. Staggered inspections were conducted in multiple time frames, consisting of both scheduled and surprise patrols. Scheduled inspections generally took place from 11:00 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. and from 5:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m., while surprise inspections were conducted immediately upon receiving public complaints. In addition, the urban managers designated critical areas—such as school entrances, intersections in commercial districts, and residential entry points—as no-vending zones, marked with prominent prohibitive signage to minimize congestion and safety risks in public spaces (

Figure 3). However, this period was witnessed by constant tension between vendors and officials, with vendors frequently forced to relocate or face penalties. This approach led to social discontent and disruption to the economic activities vital for many residents’ livelihoods.

3.2. Spatial Inclusion: The Creation of Tea City and Shenglong Vending Zones

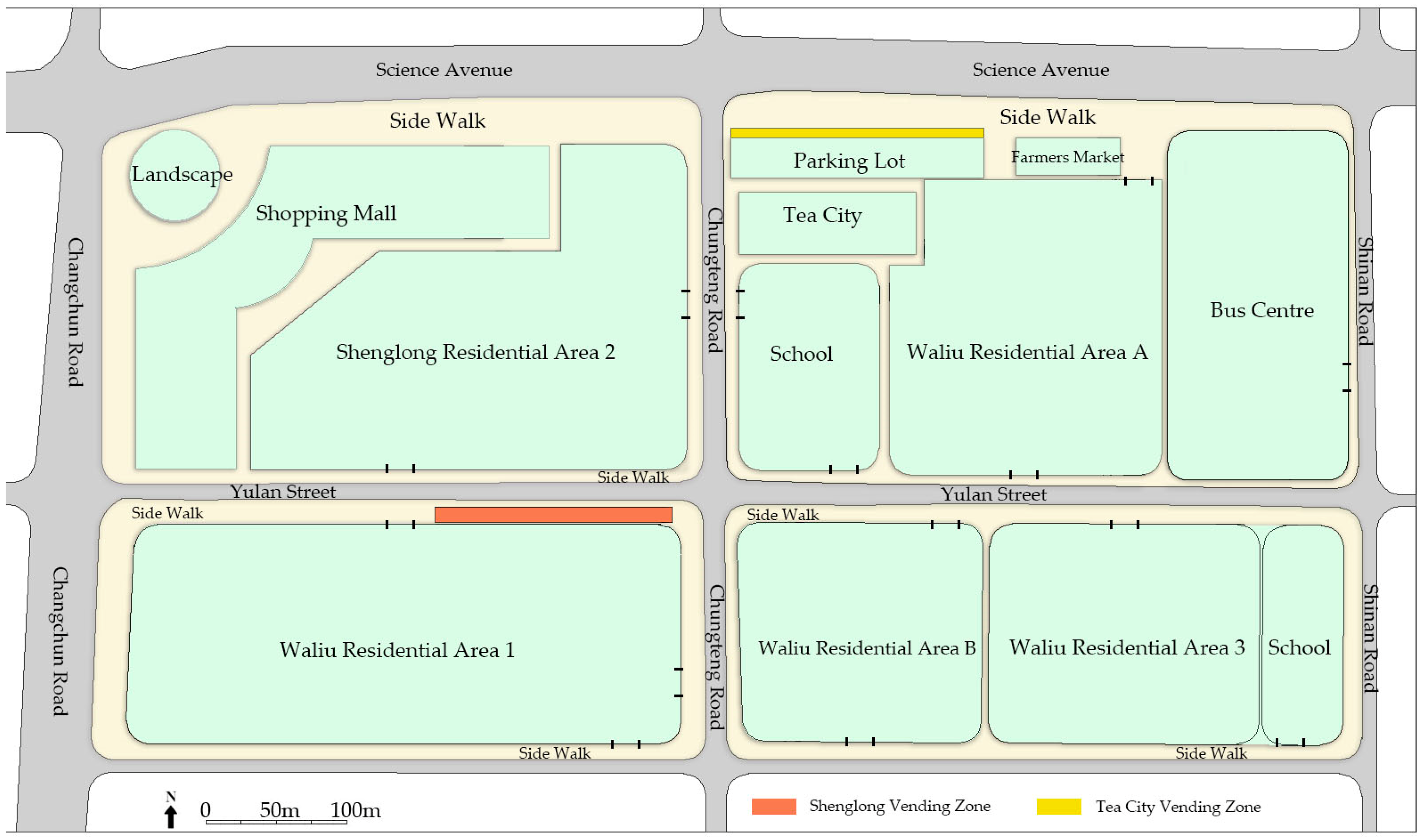

The year 2020 marked the first significant shift in the Waliu Community’s governance strategy for the surrounding environment. The establishment and inauguration of the vending zone, Tea City, at the end of this year within the community were landmark events. Three years later, the other vending zone, Shenglong, was created in September 2023. These vending zones represent a spatially inclusive approach to environment management, with specific areas allocated to legal street vending. This approach not only provides a business place to vendors but also prevents the chaotic occupation of urban public spaces. The designated Tea City and Shenglong areas are, respectively, located in the north and centre of the Waliu Community (

Figure 4). The creation of these two vending zones took into account community foot traffic, community logistics, and economic activity. The following section will provide a detailed discussion of the installation of these two zones.

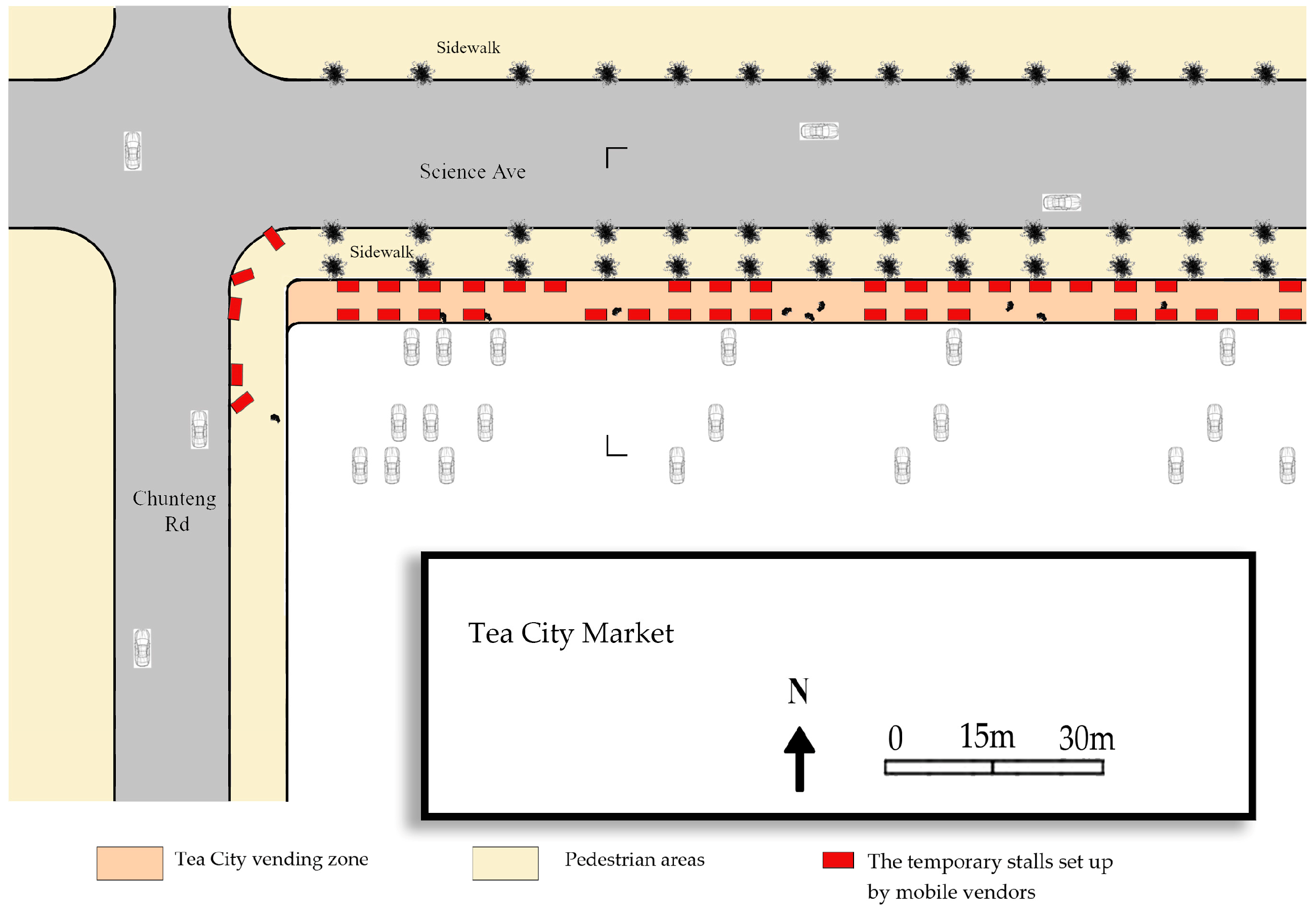

The establishment of the Tea City vending zone aimed to address the issue of street vendors gathering in the northern section of the community. This area is located close to a major transport hub and the tea-selling mall, making it one of the busiest zones for street vendors within the surrounding urban areas. Based on the ideal planning, many vending stalls are designed to line the road. As shown in

Figure 5B, each stall in the Tea City vending zone is approximately 3 m by 1.5 m in area, covering a total of about 300 square meters. This space accommodates around 20 to 30 fixed stalls for street vendors in the Waliu Community. A 3-m-wide passageway in the middle is reserved for pedestrian access. It is important to note that the temporary stalls in the Tea City area were not given line markings on the ground; instead, visual cues were used to regulate the length and width of the space each vendor could occupy.

The original sidewalk and attached landscapes in front of the Tea City were designed into an identifiable vending zone. The temporary stalls are arranged along two parallel rows from west to east.

Figure 5A illustrates the ideal setup. To the south is the dedicated parking area for the tea-selling mall. Its western entrance connects to Chunteng Road, while its northern boundary is separated from Science Avenue by green landscaping. The eastern entrance is adjacent to the entrances of a farmers’ market and a parking lot. To prevent street vendors from encroaching into the parking area, barriers have been set up to delineate vending boundaries. Additionally, vendors are prohibited from setting up stalls beyond the eastern entrance, as this would affect the operations of both the farmers’ market and the parking lot. Consumers approaching from the west, typically from Chunteng Road and the adjacent sidewalk, first encounter the street vendors at the western entrance. Interested shoppers generally move eastward along the central passage between the temporary stalls, browsing among the various goods offered by the vendors. Most of these consumers are residents of the Waliu residential area located to the south of the Tea City vending zone.

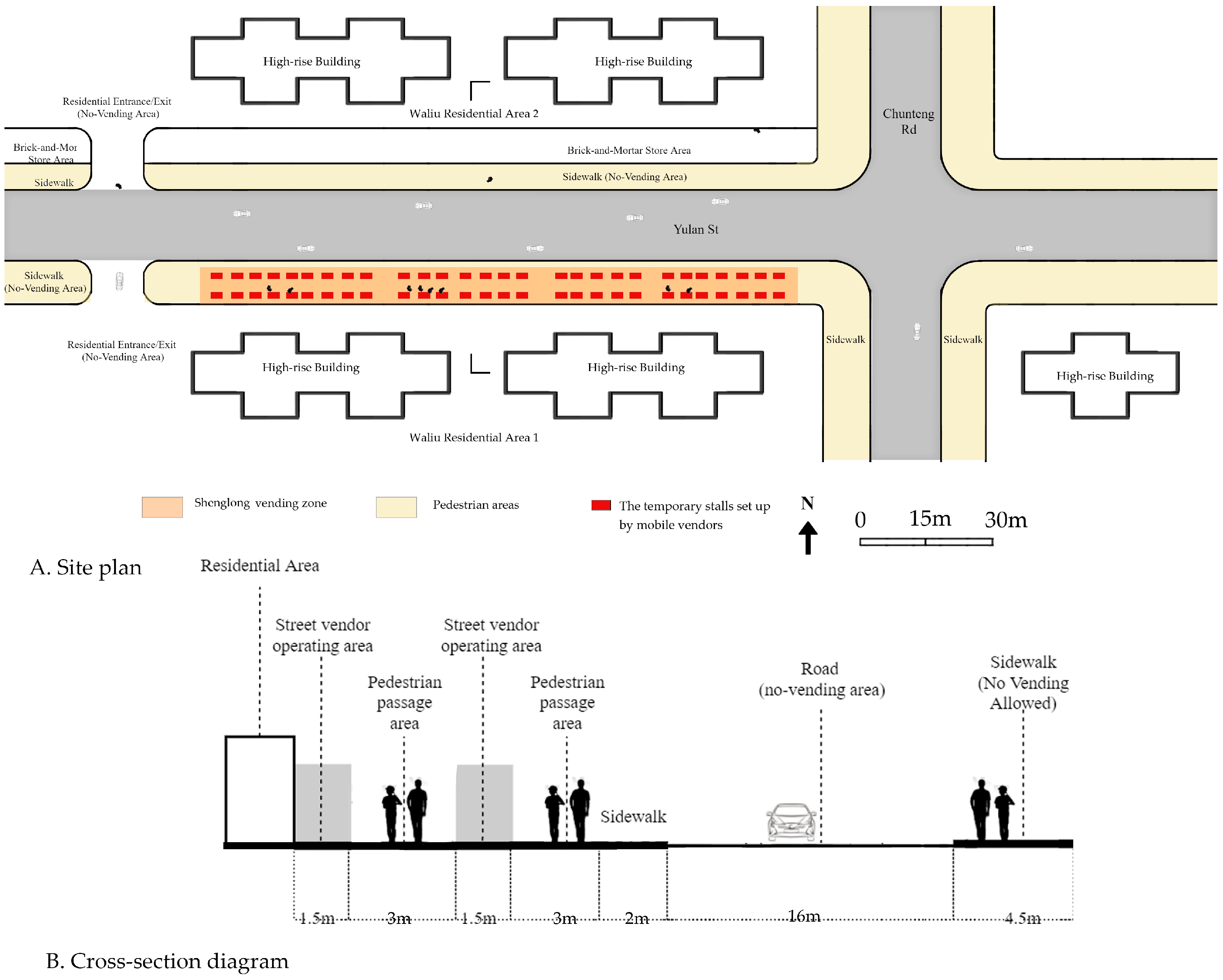

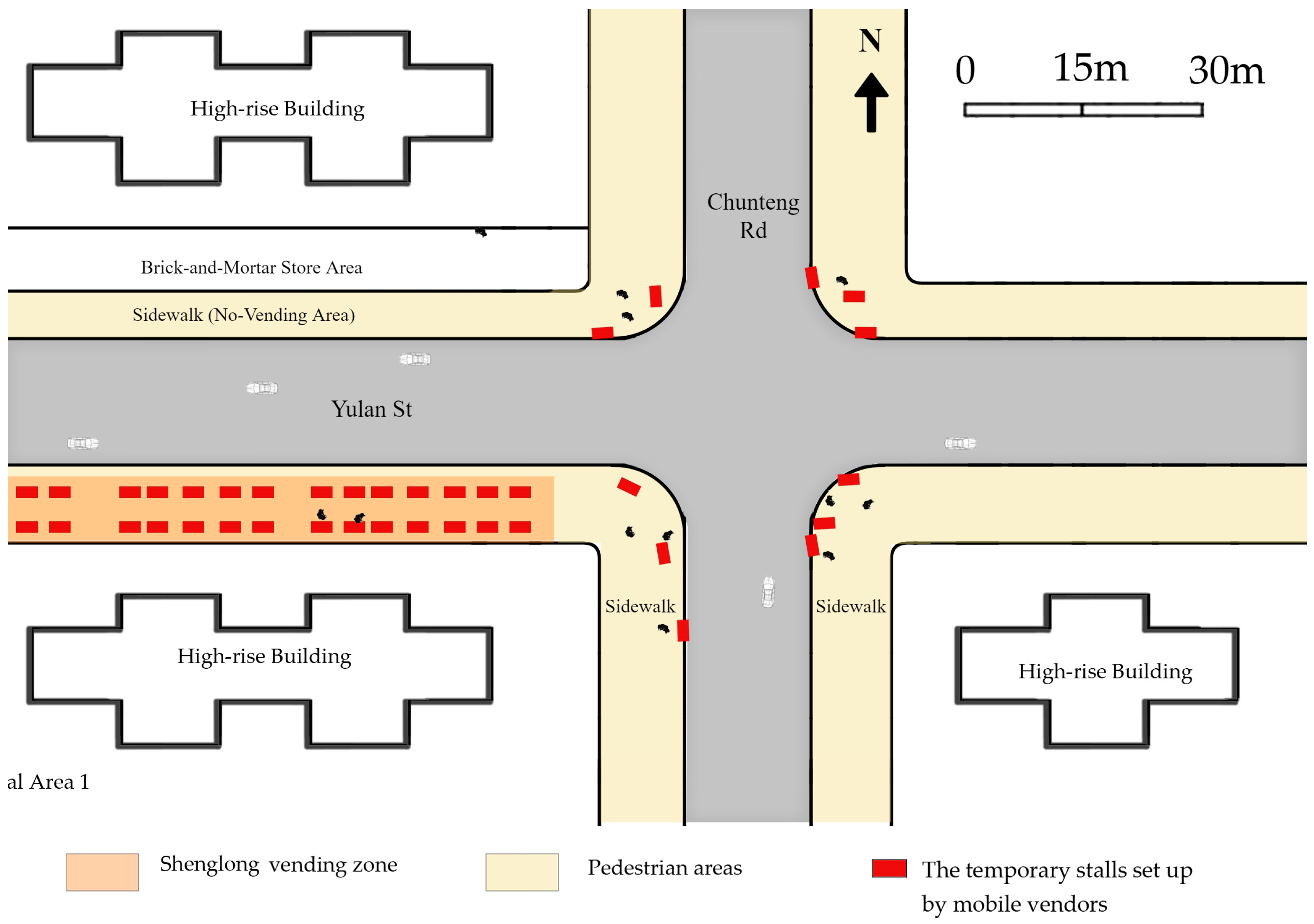

Different from the Tea City area, the primary purpose of the Shenglong vending zone is to alleviate the over-concentration of street vendors inside the Waliu Community. Shenglong is located in the central part of the community, near residential areas and key traffic routes. Each stall in this vending zone is approximately 3 m by 1.5 m in area, covering a total of about 1800 square meters (

Figure 6A). This space accommodates around 40 to 50 fixed stalls for street vendors in the Waliu Community. As in the Tea City vending zone, the temporary stalls in the Shenglong area are managed visually without ground markings to delineate each stall’s boundaries.

The temporary stalls in the Shenglong vending zone, similar to those in Tea City, are arranged along two parallel rows, running from east to west.

Figure 5A illustrates the ideal layout of the Shenglong area. The Shenglong residential area 1 and 2 are north and south to the vending zone, respectively. Separated from Yulan Street and the residential area by railings, Shenglong is a vending zone more enclosed than Tea City. So as to avoid obstructing pedestrian traffic and compromising safety, street vendors are not allowed to set up stalls at the eastern intersection or the western entrance to the Shenglong residential area. Most consumers arrive from the residential areas to the north and south, along with residents walking south from Chunteng Road to the intersection.

3.3. Environmental Managers During Spatial Inclusion

The urban environmental governance for vending activities in the Waliu Community tended to be more complicated when the two vending zones were created. During the spatial exclusion period, the vending activities and relevant public space were directly governed by the urban managers (Urban Management Department of the Wutong Subdistrict Office). Yet, when it comes to the period of spatial inclusion, management rights were allocated to the property management companies of the adjacent residential areas and tea-selling malls. The property management companies are responsible for providing a range of community and mall services including security, cleaning, and the maintenance of public facilities. They were expected to coordinate all the community services and granted authority over the daily management of vending zones. This includes allocating stalls, maintaining operational order, and overseeing health and safety concerns. This arrangement is built on the property management companies’ familiarity with the surrounding environment and their long-standing management experience. It also eased the burden of daily management on the urban managers.

However, these companies may prioritize financial gain over the best governance of vending zones. As they are profit-driven entities that generate revenue through rental fees of urban space charged to vendors, their decisions might favour interests of the companies rather than those of vendors. For this reason, it is necessary for urban managers to provide oversight and impose constraints on their actions and decisions. This oversight ensures that property management companies act in a manner consistent with urban development goals and the overall well-being of residents. Such regulation is crucial in preventing the abuse of power and ensuring that the management of vending zones aligns with prevailing standards. Meanwhile, the urban managers conduct their own routine patrols around both vending zones. The urban management officials’ jurisdiction mainly covers the shops and schools on both sides of Chunteng Road. These patrols serve two key purposes: preventing street vendors from impeding business by obstructing storefronts and ensuring that vendors do not pose traffic or food safety risks to students.

3.4. Actural Environmental Governance During Spatial Inclusion

With the creation of the Tea City and Shenglong vending zones, the use of street space has undergone significant changes. The areas provided vendors with legal spaces to operate and altered their movement patterns. Specifically, the Tea City and Shenglong have had contrasting impacts on vendor actual mobility within their respective zones (

Figure 6).

The actual land use in the Tea City vending zone is not ideally orderly. Some vendors who were unable to secure a stall within the area continue to operate near the entrances, taking advantage of the high foot traffic to increase their sales opportunities. This clustering of vendors at the entrances directly affects the spatial order and traffic flow within the vending zone. Because of the random placement of their stalls, the passageways at the entrances are further narrowed, significantly reducing the space available for pedestrians. During peak times, this often leads to congestion as pedestrians struggle to pass through the area. Furthermore, the concentration of vendors at the entrances undermines the internal operating order of the vending zone. Some vendors use this method to evade management regulations, thus creating new governance challenges.

As one vendor who has operated near the community for years shares, “When the vending zones were first established, we were happy, thinking we could finally run our business without fear of being chased away. But with limited stall space, many spots filled up quickly, forcing us to operate near the entrances or on the fringes. The high foot traffic at entrances boosts sales, but officials frequently remind us to keep order and cleanliness, and sometimes even ask us to move for traffic flow. It’s a tough situation; on one hand, we need the business, but on the other, we fear fines or losing our only place to work”.

However, a resident living near the vending zone commented, “The vending zone is convenient; we can shop for groceries or essentials whenever we need. However, the entrances are always crowded because some vendors without stalls set up there. During peak hours, it’s hard to pass through—it can get quite frustrating. We understand the vendors’ struggles but hope the authorities can better manage the entrances to prevent them from becoming new congestion points”.

The vending spatial occupation in the Shenglong zone exhibits more complex issues. Due to its proximity to residential areas, vendor movement is heavily influenced by the needs of the surrounding residents. With limited stall availability, some vendors are unable to secure spots within the vending zone. Instead, they set up their stalls on nearby sidewalks or streets, leading to traffic congestion and disorder. Also, the Shenglong zone faces pressure from the influx of vendors from the Tea City area at specific times. Between 6:30 p.m. and midnight, a large number of vendors move from Tea City to Shenglong to continue their operations, creating a relatively fixed flow of traffic. Its route runs from the north side of Chunteng Road to the southern side, occupying the surrounding roads at the intersection. While governance in the spatial inclusion stage has improved environmental conditions, vendor behaviour during peak times continues to challenge spatial order. As a surrounding community resident said: “I think setting up vending zones was a good idea; it’s not only convenient for us to buy groceries, but the environment is also much cleaner than before. However, some vendors still crowd near sidewalks during peak times, causing congestion”.

An official of urban management involved in setting up the vending zones explains, “Before these areas were established, street vendors often operated on main thoroughfares, causing significant inconvenience for residents. We received many complaints, so we had to intensify our clearing efforts. However, each time we cleared them, vendors would gather elsewhere, leading to a cycle of dislodgement. The purpose of establishing vending zones was to provide legal spaces for vendors to make a living while maintaining urban order. Management issues in reality persist, especially around the entrances. Many vendors, unable to secure a designated stall, gather near the entrances, causing congestion and disorder. Managing these areas has proven almost as challenging as it was before the vending zones were set up”.

Overall, the establishment of vending zones has effectively regulated the environmental governance for vending activities, reducing instances of disorderly operations, while the mobility and clustering of vendors outside the zones still require further management efforts. To better balance the management of vending activities both inside and outside the zones and to enhance vendor awareness of their legal obligations, the urban managers have innovatively proposed and implemented a new governance model later.

4. Spatial Self-Management: Updated Environmental Governance

Since March 2024, the Waliu Community has entered a period of spatial self-management for environmental governance. The key features of this evolution are the joint land use of the two vending zones and the shift toward making street vendors the primary actors in vending zone governance.

4.1. The Joint Operation of Vending Zones

The joint operation of the Tea City and Shenglong vending zones is the key initiative in spatial self-management. This initiative aims to enhance resource allocation efficiency and strengthen the management of street vendors by improving coordination between the two vending zones. The core principle of joint operation lies in breaking away from the previous model where each vending zone was managed independently and lacked unified oversight. Instead, it promotes cooperation between different areas to create a more integrated management system. Venders are allowed to more freely choose the zone and when they want to operate.

Complementary operating hours are one of the main characteristics of joint operations. By adjusting the operating times of the Tea City and Shenglong vending zones, the issue of vendors shifting their operations at different times was mitigated. The Tea City area operates from 7:30 a.m. to midnight, while the Shenglong area opens from 6:30 p.m. to midnight. This arrangement ensures that vendors have stable operating spaces throughout different periods of the day and reduces the need for vendors with insufficient operating spaces to move to other areas of the community.

Unified rental fees and stall management are other key features of joint operation. Street vendors are required to pay a single rental fee, allowing them to operate across both vending zones without the burden of paying twice (

Table 3). This unified management approach not only incites more vendors to operate legally within the vending zones but also effectively reduces the gathering of unauthorized vendors in other public spaces within the community. In addition, the standardized stall management system ensures the proper use of stalls. It reduces competition and conflict among vendors and promotes a more harmonious operating environment.

4.2. “Street Ambassador”

To reach the stage of spatial self-management, the urban managers have incorporated street vendors into the co-governance system. This shift marks that vendors move from passive subjects of regulation to active participants in environmental governance. In the co-governance system, street vendors are given the role of “Street Ambassador”. This role comes from the existing volunteer service program. The program invites street vendors to participate as volunteers in managing both the internal and external operations of the vending zones. The selection of volunteers follows a rotating system, beginning with the first and second stalls. Each day, two vendors from the designated stalls wear red “Street Ambassador” vests and serve as volunteers. The work of the “Street Ambassadors” is in fact not directly supervised by the urban management team and their responsibilities are more specialized. These ambassadors independently handle various tasks, such as maintaining order within and around the vending zones, advising vendors on rule compliance, ensuring cleanliness, and guiding customer traffic. By granting street vendors more management authority, this initiative promotes them from mere subjects of regulation to co-governors.

Some residents express positive views on the model of spatial self-management. One resident says, “Now, seeing vendors voluntarily clean up around their stalls, it feels like their standards have really improved. As customers, we also notice their friendliness and attentiveness—some even help watch over children”. This suggests that spatial self-management has improved physical space usage while strengthening community cohesion and residents’ acceptance of vendors.

4.3. Environmental Governance for Spatial Self-Management

As the Waliu Community reached the stage of spatial self-management, the environmental governance of vending activities experienced significant change. With the new joint operation of vending zones and the vendors becoming key governance actors, their activities became more organized and efficient. Adjustments to operational measures led to more planned and regulated vendor movement.

Figure 7 shows an intermittent chaotic distribution of vendors around the west entrance of the Tea City vending zone, where the stall layout was disorganized. The stalls were facing different directions, especially near the west entrance where vendors positioned their stalls along the pedestrian flow, disrupting foot traffic. The situation under spatial self-management governance realized the designed layout (

Figure 5), where the stall layout becomes more orderly and regulated. Stalls are neatly arranged along both sides of the walkway, uniformly facing the main direction of pedestrian traffic and ensuring the smooth passage of pedestrians.

Figure 8 offers the intermittent chaotic distribution of vendors during spatial self-management in the Shenglong vending zone. The figure shows how vendors at the stage of spatial inclusion would set up stalls haphazardly around the intersection with no clear organization. Stall placement was irregular, with some vendors occupying critical passageways at the intersection. The disorganized stalls also disrupted the flow of vehicles. This led to conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles, especially during peak hours. Under governance in the spatial self-management period, the reorganized stall layout is much more orderly and close to the designed layout (

Figure 6). Stalls are neatly arranged along both sides of the pathway, avoiding obstructing the intersection, thus freeing up space for smoother traffic flow (

Figure 9).

One community property manager remarked, “Instead of having urban management patrol daily, it’s more effective to let vendors manage their area. They value their own spaces more and will naturally remind others to follow the rules”. Additionally, vendor mobility in the Shenglong vending zone is a sign of greater flexibility and dynamism. Since the operating hours at Shenglong are essentially from 6:30 p.m. to midnight, many vendors from the Tea City vending zone move to Shenglong after closing their stalls during the day, thus forming a cross-area migration. This shift has become a new norm in spatial self-management. In summary, governance in both the Tea City and Shenglong vending zones has tended to stabilize, with a significant drop in movement and disorder.

5. Evaluation of Environmental Governance Transformation

The transition through the three governance phases within the Waliu Community illustrates the impact the different authorities and social interaction modes have on both street vendors and community residents. The key indicators of environmental governance transformation to be investigated include spatial utilization efficiency, vendor livelihood, social order and safety, and stakeholder satisfaction.

5.1. Spatial Utilization Efficiency

The transition of governance models in the Waliu Community has profoundly impacted spatial utilization efficiency. In the spatial exclusion phase, vendors were frequently displaced, leading to inefficient use of urban spaces. This top-down control approach prioritized order over effective space management. During the spatial inclusion phase, the establishment of vending zones like Tea City and Shenglong provided dedicated spaces for vendors, thus improving spatial utilization. However, limited stall availability within these zones led to suboptimal resource allocation.

The advent of spatial self-management marked a significant shift. By empowering vendors to participate in governance, stall locations became more rationally planned. Vendors, equipped with data on customer flow and traffic conditions, optimized their positions to minimize spatial conflicts. Collaboration among vendors facilitated the distribution of business areas, promoting order and efficiency (

Table 4).

5.2. Vendor Livelihood

Because the governance emphasizes “returning the road to the people” and “unifying the city appearance”, the street vendors are often regarded as “urban diseases” and are strongly excluded, their economic benefits are unstable, their livelihoods are extremely unsafe, and they are trapped in “struggling to make a living”.

Spatially inclusive governance has improved the legalization degree and business environment of stallholders, made their business time and space more controllable, gradually stabilized their livelihood base, and significantly increased their income (

Table 5).

Spatial self-management has reshaped the relationship between stallholders and cities, giving them legitimacy, normality, and dignity. With the support of technology, system and social identity, stallholders’ income has continued to increase, and their livelihood ability and families’ anti-risk ability have been significantly enhanced. Self-management satisfies the vendors’ livelihood needs and aligns with contemporary urban governance trends [

45].

5.3. Social Order and Safety

In the spatial exclusion phase, social order relied primarily on strict governance by urban managers, which in turn, led to confrontation between vendors and authorities, thus weakening social cohesion. Vendors were excluded from the regular functions of the city, making it difficult for them to form a sense of collective identity. In the spatial inclusion phase, surface-level order improved but vendors remained marginalized and lacked genuine participation rights.

A resident who has closely followed the community’s changes remarks, “The impact of spatial self-management on the streets is clear. In the past, there was constant conflict between vendors and officials and cleanliness was inconsistent. Now, vendors voluntarily clean their stalls and maintain order. The ‘Street Ambassadors’ are especially diligent. The vending zones now feel spacious and organized, without the crowding and mess of before. As residents, we appreciate not only the improvement in physical space but also the positive shift in the community atmosphere. Vendors have truly become ‘members’ of the community, and we’re more supportive of their livelihoods”. The self-governing vendors are no longer seen as disruptors of order but as protectors and beneficiaries of well-maintained streets. This collaborative model fosters trust and understanding between vendors and urban management, integrating vendors as part of the city’s social fabric and significantly enhancing community social order and collective identity [

46].

Due to the strong mobility of vendors, the lack of spatial guidance, and the absence of interaction between law enforcement and residents, a high-frequency, low-intensity but widely distributed “urban friction belt” has been formed, resulting in chaos and low public satisfaction (

Table 6). The governance order has been initially established, and the frequency of conflicts has decreased, but “street vendors operating in the district side” and “morning and evening peak overtime operation” are still the main incentives, and the spatial delineation and institutional design still need to improve the precision. After the governance service, the legitimacy, and responsiveness of the system are significantly improved, the “order identity” between the public and vendors and the community cohesion are enhanced, and the quality of urban life and safety are improved simultaneously.

5.4. Stakeholder Satisfaction

The environmental governance of the Waliu Community for vending activities began with the spatial exclusion phase, where the urban management department implemented top-down regulations to maintain public order. As vendors adapted their strategies, it became clear that more sustainable and inclusive approaches were needed, leading to the adoption of spatial inclusion policies to better balance urban order with vendor livelihoods. In this phase, the Tea City and Shenglong vending zones provided vendors with legitimate spaces to operate. This change improved spatial utilization and significantly eased tensions between authorities and vendors. An urban manager responsible for the daily oversight of the vending zones observes, “Since we implemented spatial inclusion, vendor awareness has noticeably improved. Before, we had to patrol daily to enforce cleanliness and order, but now we only need to check in occasionally. Vendors voluntarily maintain their stalls and keep pathways clear”.

With further governance initiatives, the community, at last, entered the spatial self-management phase, where power was more widely distributed and vendors participated in governance as “Street Ambassadors”. This allowed vendors to transition from marginalized, managed subjects to active governance participants, thus restructuring the power dynamics in the governance of urban street vending [

47,

48]. That same urban manager says, “Those appointed as ‘Street Ambassadors’ actively assist with managing customer flow and advising other vendors. This self-management approach has lightened our workload but has also shifted vendors’ perspectives; they no longer see us as adversaries but as partners in managing the area. This trust and sense of involvement have greatly stabilized the vending zones”. Under this model, vendors gained opportunities to participate in urban environmental governance legally and resident acceptance of vendors gradually increased. Questionnaire surveys for vendors and residents in the community show that in the stage of spatial self-management, the satisfaction of both vendors and residents on environmental governance has increased significantly as compared to before (

Table 7 and

Table 8). While the spatial inclusion phase led to initial enhancements by offering dedicated vending spaces, the persistence of challenges and the absence of complete vendor integration led to a relatively minor increase in vendor satisfaction when compared to the spatial exclusion phase.

The assessment of environmental governance transformation in the Waliu Community highlights the profound influence of the transition from spatial exclusion to spatial inclusion and eventually to spatial self-management. The spatial exclusion stage, marked by rigorous enforcement measures, prioritized urban order at the cost of spatial efficiency and social harmony. In contrast, the spatial inclusion stage introduced designated vending areas, which enhanced spatial utilization and vendor livelihoods yet failed to cultivate genuine community participation. The most significant advancements were achieved during the spatial self-management stage, where vendors were enabled to actively participate in governance. This collaborative model not only improved spatial utilization efficiency but also strengthened vendor livelihoods, enhanced social order and safety, and increased stakeholder satisfaction. The transition thereby exemplifies a shift towards a more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient urban governance framework that is in line with contemporary urban management objectives.

6. Discussion

The spatial self-management model has delivered significant improvements in spatial utilization, social order, and collective identity. Nonetheless, it still presents several challenges. First, the distribution of power in multi-party governance remains uneven due to variations in individual capacities, resource allocation, and cultural differences that hinder certain groups from fully participating in decision-making. Second, as vendors and residents become more involved in governance, the boundaries of responsibilities may blur, resulting in ambiguity in accountability in urban environmental management. Third, vendor stability remains a concern: factors, such as fluctuating market demand and financial conditions, can drive vendors out of the governance system, compromising long-term management efforts. From the government’s perspective, adapting governance models has alleviated social tensions, enhanced management efficiency, and responded more effectively to public needs. Through innovative governance strategies, the government redistributes responsibilities among stakeholders, promotes resource optimization, and fosters greater public participation. These efforts contribute to enhancing social harmony and stability, aligning with broader national development goals.

In contrast to the existing literature on street vendor governance, this study accentuates the distinctive trajectory of the Waliu Community, evolving from spatial exclusion to spatial inclusion and eventually to spatial self-management. Whereas previous research typically concentrates on the implementation and efficacy of individual governance models, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of the evolution and societal implications of diverse governance strategies over time. Furthermore, by highlighting the role of vendor empowerment and collaboration, this study enhances the understanding of inclusive and participatory urban governance, which is increasingly regarded as a crucial aspect of sustainable urban development.

7. Conclusions

The environmental governance transformation of vending zones in the Waliu Community demonstrates the positive outcomes achieved by shifting from spatial exclusion to spatial inclusion and ultimately to a spatial self-management governance model. While the spatial exclusion stage ensured short-term order, its top-down control approach led to social division and spatial inefficiency. The spatial inclusion stage improved spatial efficiency and social relations by designating legal areas for vendors to operate in, yet it still lacked community participation. In contrast, the spatial self-management governance model, through empowerment and collaboration, establishes a multi-stakeholder framework that not only enhances space-use efficiency but also strengthens social cohesion.

The environmental governance evolution, in addition, reflects significant shifts in government attitudes of authorities towards urban management. Over time, the power dynamics among stakeholders, including local authorities, street vendors, and residents, have steadily evolved, gradually reaching a balanced state. The latest governance strategy in the Waliu Community suggests that spatial self-management can simultaneously maintain urban order, address vendors’ livelihood needs, and improve residents’ quality of life. Its flexibility and inclusivity optimize community traffic, improve waste collection, and build consensus and collaboration that promotes sustainability. Thus, spatial self-management presents a sustainable and inclusive solution for governance of street vending activities. It adapts well to complex social environments and diverse demands, making it a more suitable and resilient model for urban environmental governance in the country.

While this study offers valuable perspectives on the evolution of urban vending zone governance, it does have certain constraints. The data collection was confined to the Waliu Community in Zhengzhou, and thus, might not be applicable to other urban circumstances. Future research should broaden the study area to incorporate more diverse urban environments to improve the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, a longitudinal study over a prolonged period could furnish a deeper comprehension of the long-term sustainability and challenges of spatial self-management models.