Research on the Evolution Characteristics of Policy System That Supports the Sustainability of Digital Economy: Text Analysis Based on China’s Digital Economy Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Analytical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypotheses

2.1.1. Theory of Policy Objectives and Agenda Setting

2.1.2. Theory of Policy Tools

2.1.3. Theory of an Institutional Collective Action Framework

2.1.4. Policy Implementation Theory

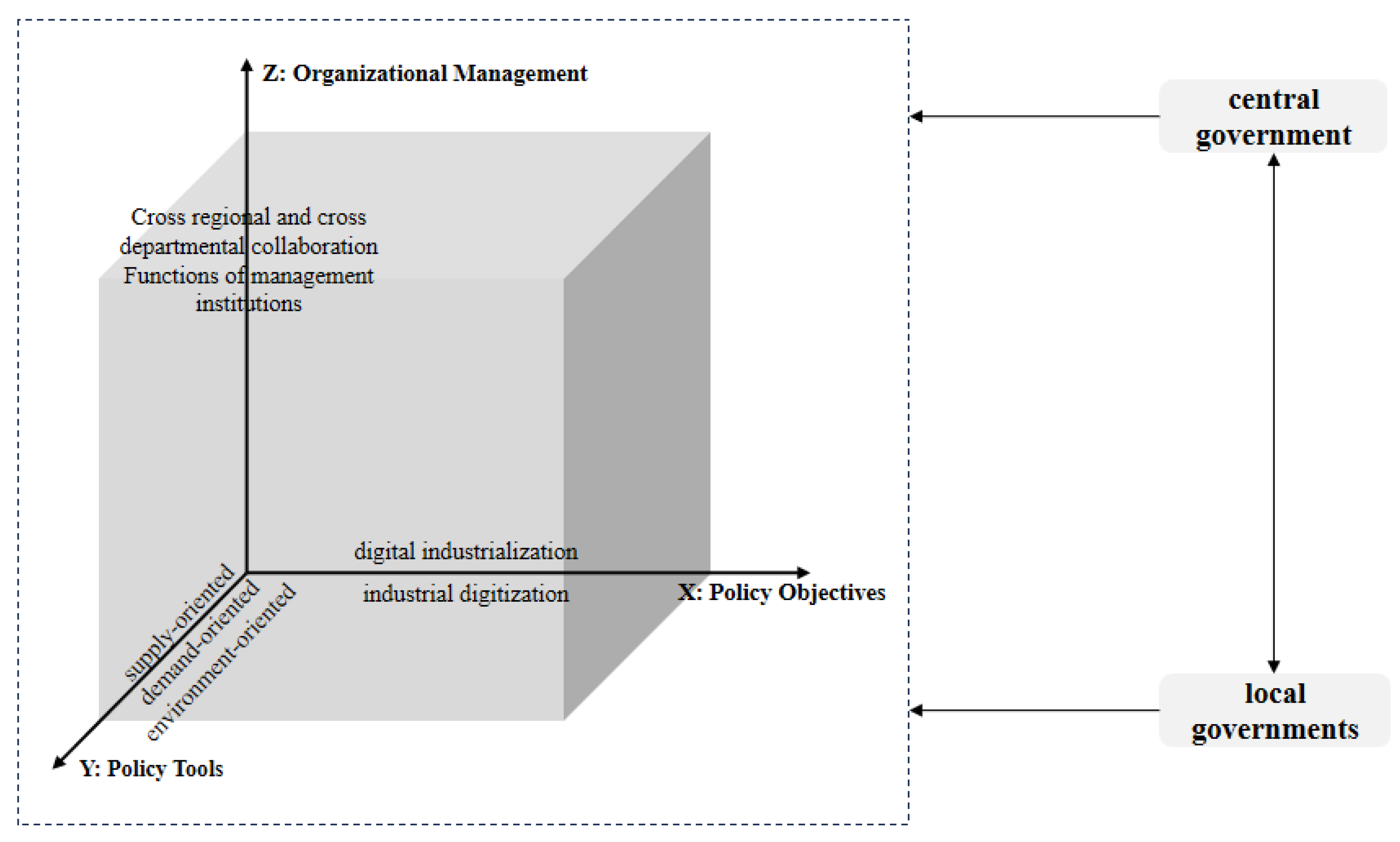

2.2. An Analysis Framework for Digital Economy Policies

2.2.1. X Dimension: Policy Objectives

2.2.2. Y Dimension: Policy Tools

2.2.3. Z Dimension: Organizational Management

2.2.4. Comparative Analysis of Central and Local Policies

3. Research Design

3.1. Selection of Digital Economy Policy Samples

3.2. Text Analysis and Dictionary Construction

3.2.1. Text Analysis Method

3.2.2. Logic of Dictionary Construction

- A.

- Primary Coding: Broad Category Classification

- B.

- Secondary Coding: Subcategory Classification

- C.

- Dictionary Entries: Keywords for Frequency Statistics

4. Finding and Discussion

4.1. Basic Situation and International Comparison of Digital Economy Policies

4.1.1. Basic Situation of Digital Economy Policies

4.1.2. International Comparison of Digital Economy Policies

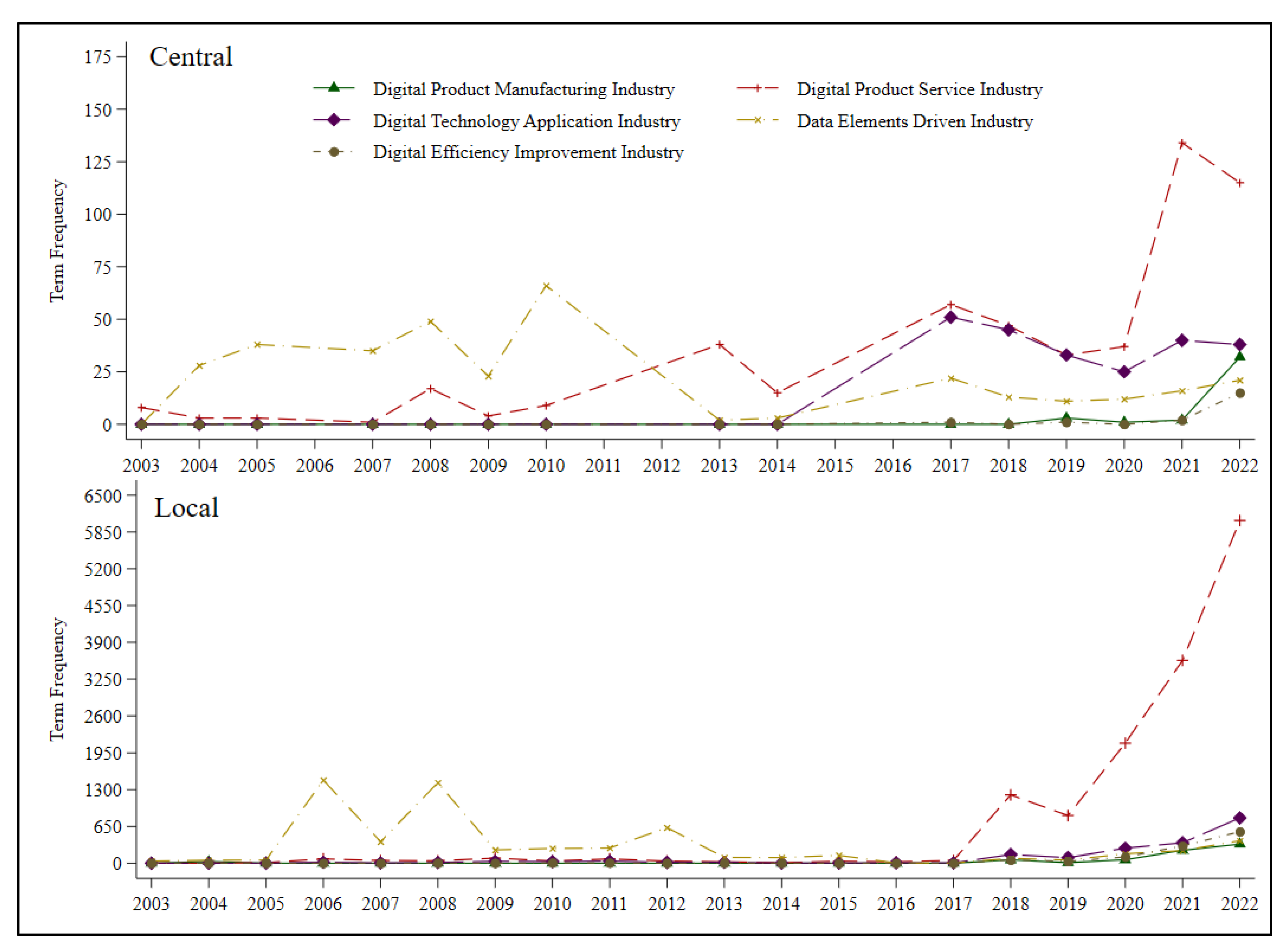

4.2. Analysis of Digital Economy Policy Objectives

4.2.1. Education and Healthcare as Primary Goals: Divergence in Central and Local Priorities

4.2.2. Central Policy Goals Show Greater Variation, with a Focus on Digital Product Services

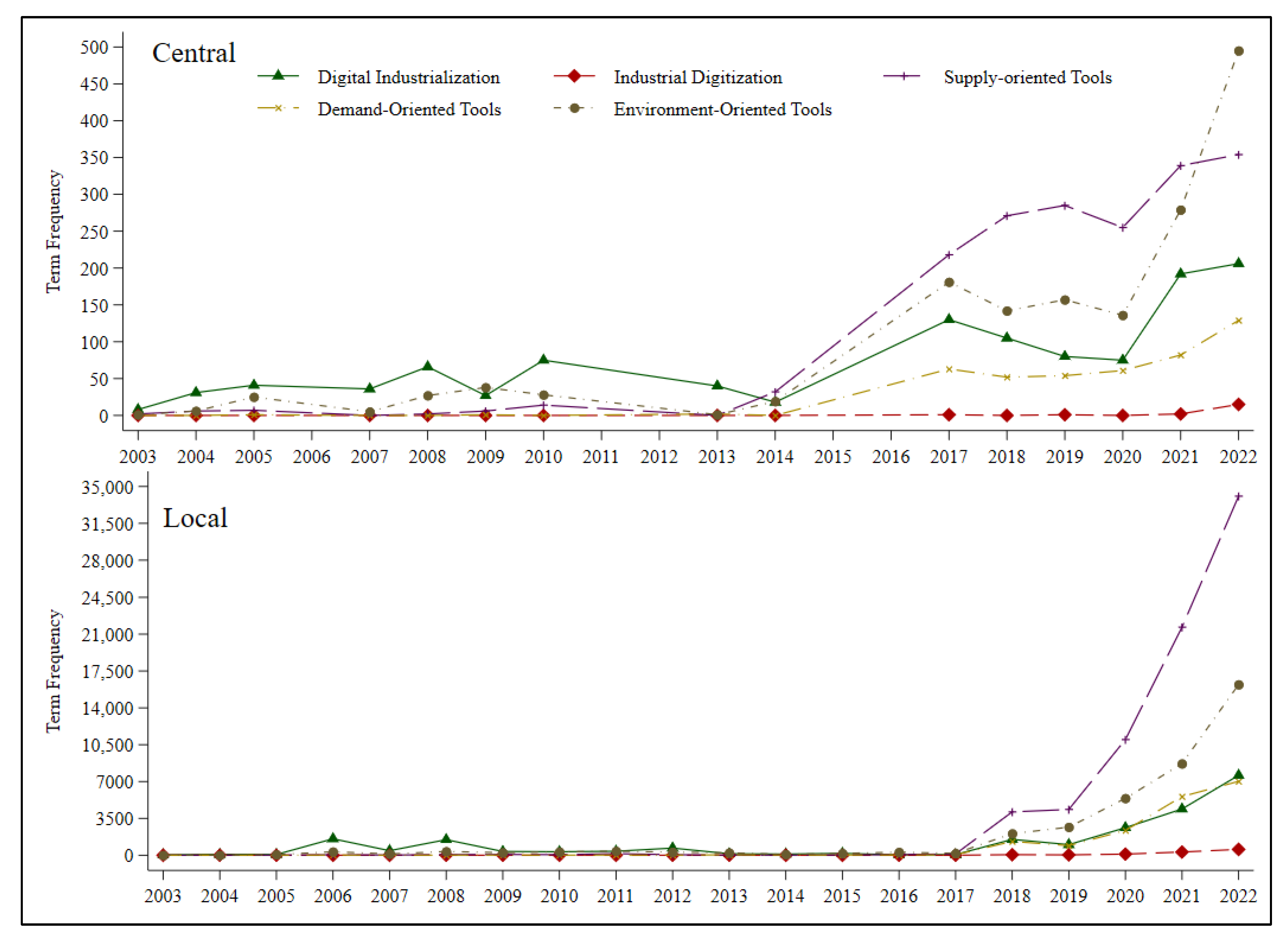

4.3. Analysis of Digital Economy Policy Tools

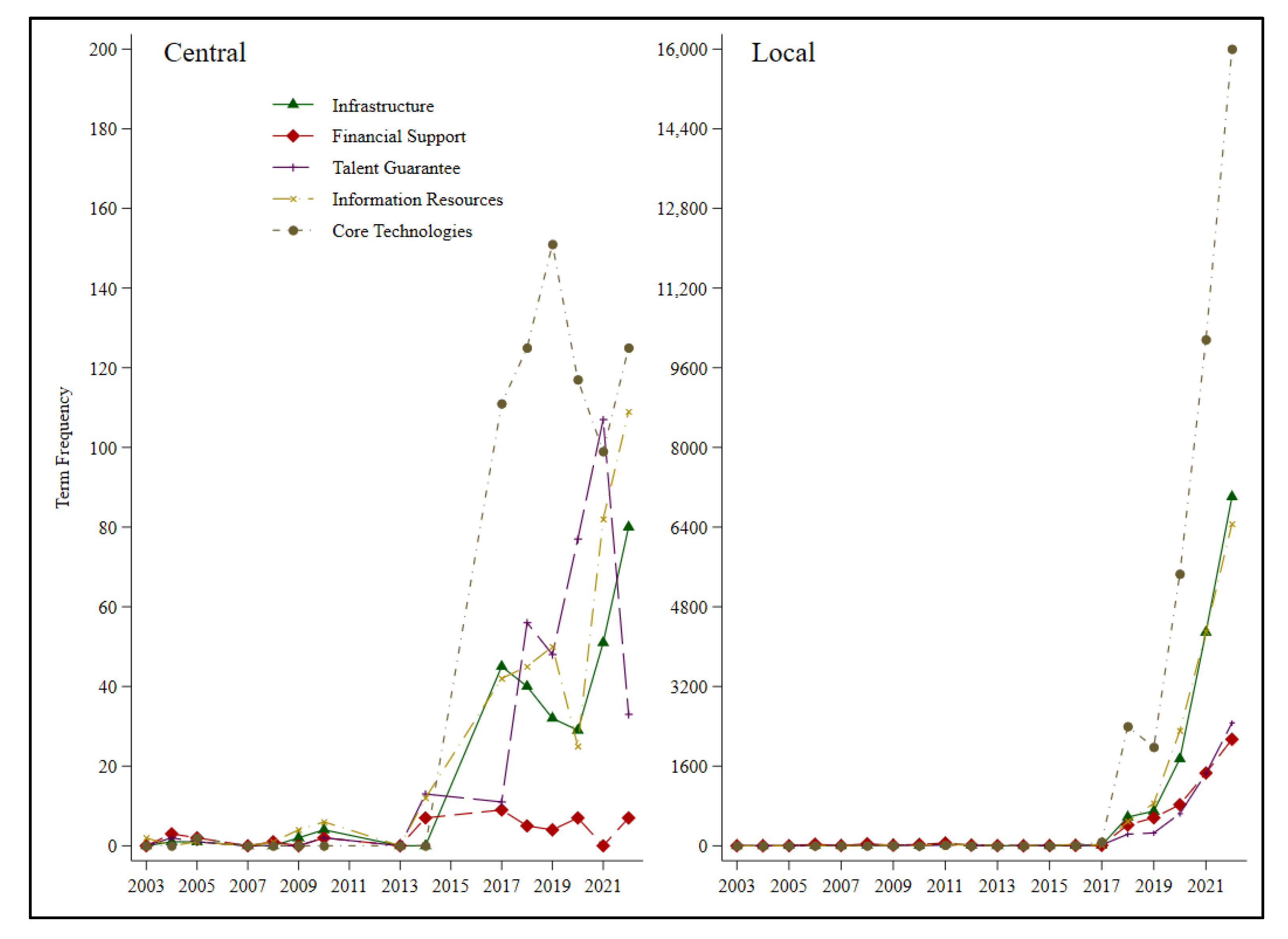

4.3.1. Supply Side Policy Tools: Variations in Stability, with a Unified Focus on Core Technologies

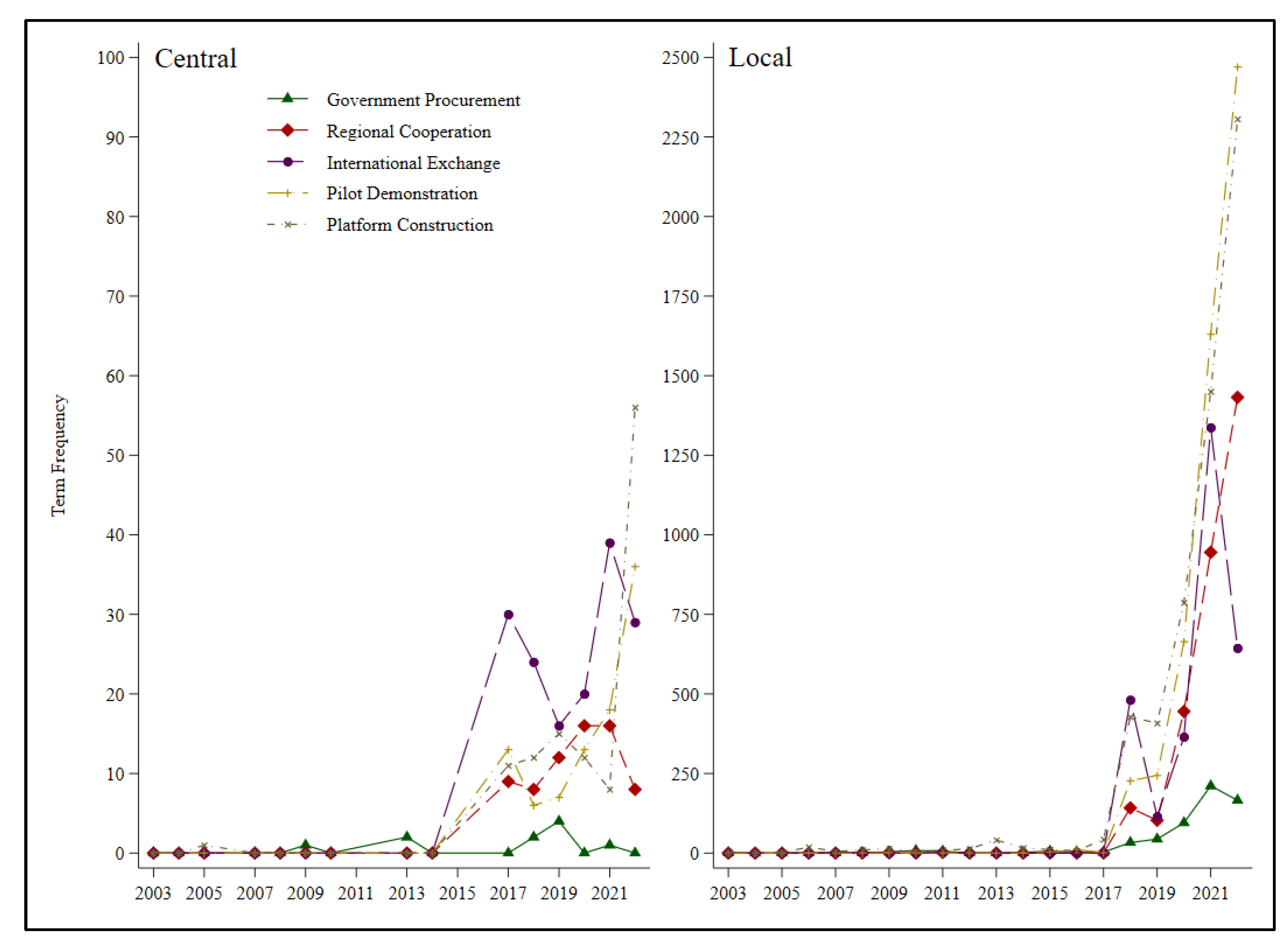

4.3.2. Demand-Side Policy Tools: Promoting Digital Economy Development Through Pilots and Platform Construction

4.3.3. Environmental Policy Tools: Common Focus on Information Security and More Diverse Tools in Local Policies

4.4. Analysis of the Organizational Dimensions of Digital Economy Policies

4.4.1. Decentralized Management Institutions: Urgent Need to Clarify Central–Local Data Institution Relationships

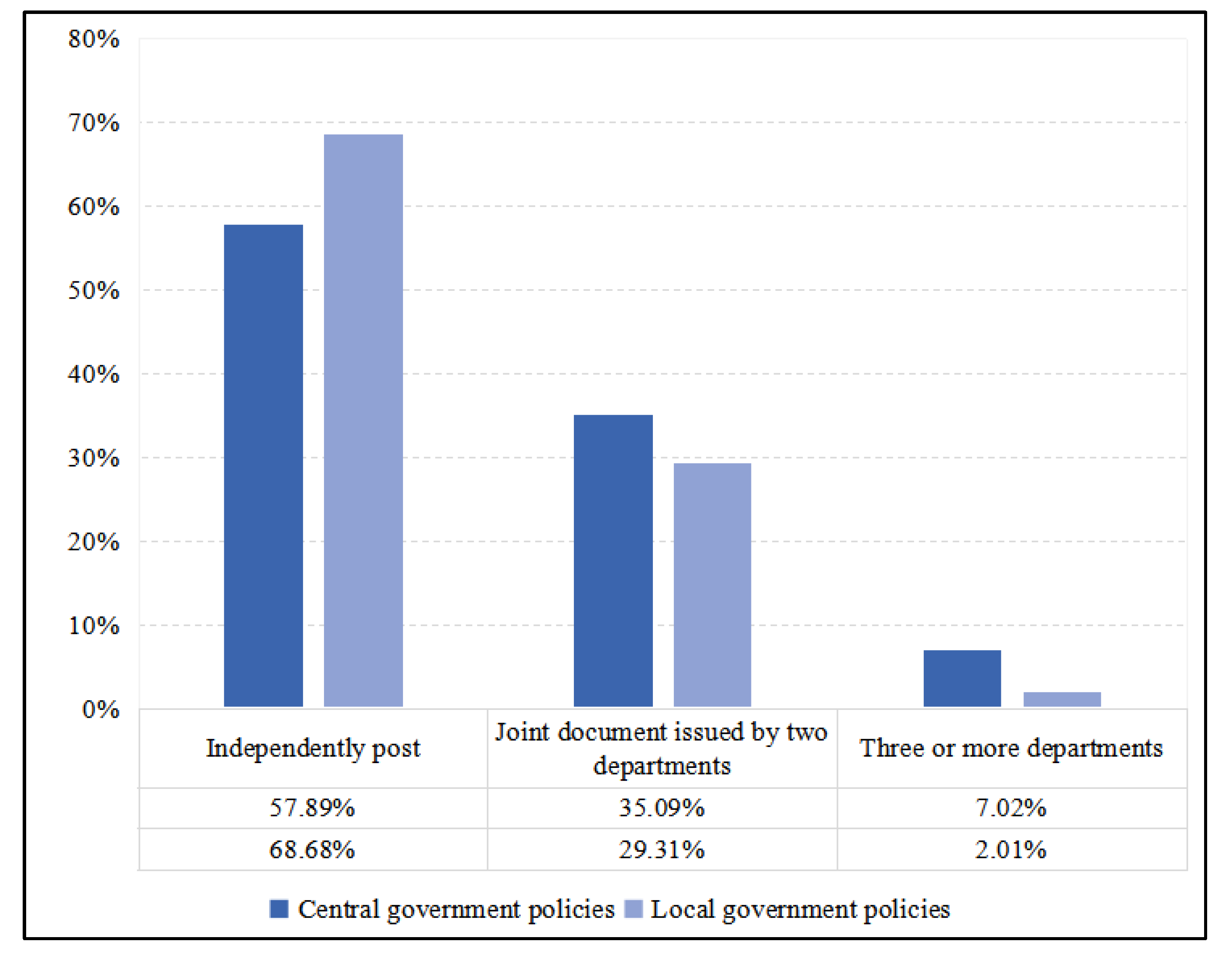

4.4.2. Numerous Involved Departments and Insufficient Cross-Departmental and Cross-Regional Coordination

4.4.3. The Continuity of Policies in Some Areas Is Not Strong, and There Are Differences Between Central and Local Policies

4.5. Empirical Analysis of the Evolution of Digital Economy Policies

4.5.1. Verification of Annual Differences in Digital Economy Policies

4.5.2. Analysis of Driving Factors for the Evolution of Digital Economy Policies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, M.; Zhang, C. Can linguistic big data empower digital economy?: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 1771–1787. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y. Digital economy and urban innovation level: A quasi-natural experiment from the strategy of “Digital China”. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Tan, Q. Can the digital economy accelerates China’s export technology upgrading? Based on the perspective of export technology complexity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 199, 123052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Yimamu, N.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Irfan, M.; Hao, Y. Digitalization and sustainable development: How could digital economy development improve green innovation in China? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1847–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiyao, Q.; Benrui, C. Research on the impact of digital technology applications on firms’ dual innovation in the digital economy context. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Rao, J.; Wan, L. The digital economy, enterprise digital transformation, and enterprise innovation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 2875–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Zhou, Y.X. Measurement Method and Application of a Deep Learning Digital Economy Scale Based on a Big Data Cloud Platform. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2022, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Guo, B.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y. The impact of digital economy on the export competitiveness of China’s manufacturing industry. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 7253–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, J.; Xu, Y.Y. The effect of the digital economy on services exports competitiveness and ternary margins. Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xia, X.; Shi, K.; Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Yang, L.; Cifuentes-Faura, J. Identifying the path choice of digital economy to crack the “resource curse” in China from the perspective of configuration. Resour. Policy 2024, 91, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, J. Unleashing the potential: Exploring the nexus between low-carbon digital economy and regional economic-social development in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, T.J. Upgrading strategies for the digital economy. Glob. Strategy J. 2021, 11, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M. Improving market performance in the digital economy. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 62, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, P.R.; Oliver, S. Trade, policy, and economic development in the digital economy. J. Dev. Econ. 2023, 164, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Al-Duais, Z.A.M.; Zhu, X.; Lin, S. Digital economy’s role in shaping carbon emissions in the construction field: Insights from Chinese cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.N.; Ma, X.Y.; Liu, J.M. How Can the Digital Economy and Human Capital Improve City Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Song, J.; Jiang, T.; Baloch, M.A. Environmental Sustainability Across BRICS Economies: The Dynamics Among the Digital Economy, Education, and CO2 Emissions. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, F.; Yu, J.; Liu, A. Examining the Impact of Digital Economy on Environmental Sustainability in China: Insights into Carbon Emissions and Green Growth. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.X.; Gao, H.F.; Yuan, D. Catalytic role of the digital economy in fostering corporate green technology innovation: A mechanism for sustainability transformation in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Zhang, H. How does the digital economy affect the sustainability of pensions? Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. The New Digital Economy and Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fan, H.; Zhao, Q. Seeing green: How does digital infrastructure affect carbon emission intensity? Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Singh, S. Genome privacy: Challenges, technical approaches to mitigate risk, and ethical considerations in the United States. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1387, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, V. Institutions, Incentives, and Policy Entrepreneurship. Policy Stud. J. 2016, 44, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Wang, T.; Fu, X.; Li, G. Research on quantitative evaluation of digital economy policy in China based on the PMC index model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Cao, Y. Coordinated research on digital economic policies in the Yangtze River Delta region of China. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Taipei, Taiwan, 11–14 June 2024; pp. 995–999. [Google Scholar]

- Sterlacchini, A. R&D, higher education and regional growth: Uneven linkages among European regions. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.F.; Yang, Y. Quantitative Evaluation of Digital Economy Policy in Heilongjiang Province of China Based on the PMC-AE Index Model. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241234435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y. Quantitative Evaluation of Digital Economy Policies in the Tourism Industry Using the TF-IDF and PMC Index Model. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 189636–189650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayla, D. How the Digital Economy Challenges the Neoliberal Agenda: Lessons from the Antitrust Policies. J. Econ. Issues 2022, 56, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Porananond, P. Competition law and policy of the ASEAN member states for the digital economy: A proposal for greater harmonization. Asia Pac. Law Rev. 2023, 31, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkova, E.G.; Sergi, B.S. A digital economy to develop policy related to transport and logistics. Predict. Lessons Russia. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horoshko, O.I.; Horoshko, A.; Bilyuga, S.; Horoshko, V. Theoretical and methodological bases of the study of the impact of digital economy on world policy in 21 century. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.C. Digital policy in European countries from the perspective of the Digital Economy and Society Index. Policy Internet 2022, 14, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gstrein, O. Data autonomy: Beyond personal data abuse, sphere transgression, and datafied gentrification in smart cities. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2024, 26, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y. Computational data privacy in wireless networks. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2017, 10, 865–873, Peer-to-peer networking and applications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liu, P.; Zhu, F. Policy objective bias and institutional quality improvement: Sustainable development of resource-based cities. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaggård, Å. The Multiple Streams Framework and the problem broker. Eur. J. Political Res. 2015, 54, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koebele, E. When multiple streams make a river: Analyzing collaborative policymaking institutions using the multiple streams framework. Policy Sci. 2021, 54, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, A. Agenda building, source selection, and health news at local television stations—A nationwide survey of local television health reporters. Sci. Commun. 2004, 25, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguin, K.; Howlett, M. Enhancing Policy Capacity for Better Policy Integration: Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in a Post COVID-19 World. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Ahmad, K.; Khan, N. Natural resources, geopolitical conflicts, and digital trade: Evidence from China. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104708. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.; Yi, C. Adaptive Social Innovation Derived from Digital Economy and Its Impact on Society and Policy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höchtl, J.; Parycek, P.; Schöllhammer, R. Big data in the policy cycle: Policy decision making in the digital era. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2016, 26, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, P. All tools are informational now: How information and persuasion define the tools of government. Policy Politics 2013, 41, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Can public service efficiency measurement be a useful tool of government? The lesson of the spottiswoode report. Public Money Manag. 2002, 22, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R.O.Y.; Zegveld, W. An assessment of government innovation policies. Rev. Policy Res. 1984, 3, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.; Teasdale, S. Dynamic persistence in UK policy making: The evolution of social investment ideas and policy instruments. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, R.; Delaney, A. Mapping the evidence of climate change adaptation policy instruments in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 083005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shi, B. Complex relationship among digital economy, policy tools and eco-efficiency: An in-depth analysis of 275 Chinese cities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. The Institutional Collective Action Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Swann, W.L.; Weible, C.M. Updating the Institutional Collective Action Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2022, 50, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. Useful Complaints: How Petitions Assist Decentralized Authoritarianism in China. China Q. 2017, 229, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertha, A. “Fragmented Authoritarianism 2.0”: Political Pluralization in the Chinese Policy Process. China Q. 2009, 200, 995–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J. Improving Policy Design and Building Capacity in Local Experiments: Equalization of Public Service in China’s Urban-rural Integration Pilot. Public Adm. Dev. 2017, 37, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’toole, L. The theory-practice issue in policy implementation research. Public Adm. 2004, 82, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M. Moving policy implementation theory forward: A multiple streams/critical juncture approach. Public Policy Adm. 2019, 34, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.; Reiser, B.; Reimer, T. Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing implementation research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2002, 72, 387–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E. The Politics of Central Tax Collection in China since 1994: Local collusion and political control. J. Contemp. China 2016, 25, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, T.; Lü, X. Taxation without representation: Peasants, the central and the local states in reform China. China Q. 2000, 163, 742–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Dynamics in Central-Local Division of the Authority of EIA Approval in China. J. Environ. Law 2019, 31, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Feihu, Y.; Yating, L. Digital economy, government efficiency, and regional administrative monopolies: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoaho, K.; Gritsenko, D.; Mäkelä, E. Topic modeling and text analysis for qualitative policy research. Policy Stud. J. 2021, 49, 300–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Shen, Y. Research on the Evolution of Government Attention in China’s Science, Technology and Innovation Policy: A Text Analysis (1983–2022). Ind. Eng. Innov. Manag. 2024, 7, 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Ye, F. China’s education policy-making: A policy network perspective. J. Educ. Policy 2017, 32, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapscott, D. The Digital Economy: Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, P.; Li, R.; Chen, A. Digital transformation and economic growth Efficiency improvement in the Digital media era: Digitalization of industry or Digital industrialization? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, L.; Ling, X.; Qin, X.; Li, M. Digitalization capability and digital product and service innovation performance: Empirical evidence from China. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024, 31, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helser, S.; Hwang, M. AI and Big Data: Synergies and Cybersecurity Challenges in Key Sectors. IEEE Trans. Technol. Soc. 2024, 6, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Dong, Y. Digital economy and risk response: How the digital economy affects urban resilience. Cities 2024, 155, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Ueno, A.; Dennis, C.; Alamanos, E.; Curtis, L.; Foroudi, P.; Kacprzak, A.; Kunz, W.H.; Liu, J.; Marvi, R.; et al. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary perspective and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Policy Name | Issuing Authority | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Opinions on Accelerating Digital Economy Development | CPC Guizhou Provincial Committee and Guizhou Provincial Government | April 2017 |

| Zhejiang Province’s Five-Year Doubling Plan for the Digital Economy | General Office of Zhejiang Provincial Government | September 2018 |

| Policies to Accelerate Digital Industrial Development via Industrial Internet | Lanzhou Industrial and Information Technology Commission | January 2019 |

| Beijing Action Plan for Promoting Digital Economy Innovation and Development (2020–2022) | Beijing Municipal Bureau of Economy and Information Technology | September 2020 |

| Guidelines for Foreign Investment Cooperation in the Digital Economy | Ministry of Commerce, Cyberspace Administration of China, and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology | July 2021 |

| Measures to Accelerate the Development of Software and Emerging Digital Industries | Xiamen Municipal Government | March 2022 |

| Dimension | Primary Coding | Secondary Coding | Example Keywords | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Objectives | 1. Digital Industrialization | (1) Digital Product Manufacturing | Computer manufacturing and information security devices | 62 |

| (2) Digital Product Services | Computer software and communication equipment retail | 17 | ||

| (3) Digital Technology Applications | Software development and internet data services | 28 | ||

| (4) Digital Resource-Driven Industries | Internet retail and security system monitoring | 29 | ||

| 2. Industrial Digitization | (5) Efficiency Enhancement Industries | Smart agriculture and e-government systems | 53 | |

| Policy Tools | 3. Supply Oriented Tools | (6) Infrastructure | Cloud computing and intelligent facilities | 36 |

| (7) Funding Support | Policy funding and research funding | 25 | ||

| (8) Talent Resources | Talent training and recruitment systems | 60 | ||

| (9) Information Resources | Data sharing and open data policies | 28 | ||

| (10) Core Technologies | Blockchain, big data, and AI | 29 | ||

| 4. Demand-Oriented Tools | (11) Government Procurement | Service outsourcing and public procurement | 7 | |

| (12) Regional Cooperation | Regional cooperation and tech partnerships | 31 | ||

| (13) International Exchanges | Digital Silk Road and global partnerships | 25 | ||

| (14) Pilot Demonstrations | Model enterprises and industry benchmarks | 11 | ||

| (15) Platform Building | Digital innovation platforms | 43 | ||

| 5. Environment-Oriented Tools | (16) Financial Support | Venture funds and M&A investment | 51 | |

| (17) Tax Incentives | R&D tax deductions and tax exemptions | 21 | ||

| (18) Organizational Structures | Coordination groups and leadership roles | 21 | ||

| (19) Information Security | Data security and privacy protections | 60 | ||

| (20) Strategic Services | Public awareness campaigns and policy advocacy | 35 | ||

| (21) Intellectual Property | Patent protection and copyright enforcement | 17 | ||

| (22) Regulatory Frameworks | Funding oversight and system regulations | 48 |

| Country/Region | Main Features | Focus on Key Areas and Policy Tools |

|---|---|---|

| America | Emphasize innovation strategy, take the lead in popularizing the concept of digital economy, and was the first to lay out digital economy planning | Building an innovative ecosystem; strengthen the collaborative cooperation between industry, academia and research; loose regulation; leading industry standards; supporting small and medium-sized enterprises; implement tax incentives; expand financing channels; strengthen intellectual property protection; promote international cooperation and trade |

| Britain | Drive socio-economic development through digital innovation and clarify the construction of a digital powerhouse | Increase capital investment; emphasize brand culture; focus on areas such as mobile communication networks, the Internet of Things, enterprise service transformation, and data analysis |

| Germany | The anti-monopoly regulation of the digital economy is at the forefront of the world | Economic anti-monopoly regulation; pay attention to consumer protection; effective regulation of data monopoly behavior |

| Japan | The digital strategy is closely related to economic security policies | Emphasize the security of digital technology products; strengthen the construction of export control capacity; tightening talent policies; establish a multi-level technology alliance; strengthening international cooperation |

| Singapore | Ranked 1st in global competitiveness in the field of digital economy regulation | strengthen talent, technology, regulation, and digital infrastructure construction; pay attention to externalizing domestic digital rules |

| European Union | Leading in the ability to regulate and govern the digital economy and orderly construction of the digital single market | Pay attention to market norms and competition regulation; building a unified digital governance framework; emphasize digital security, transparency of platform rules, and privacy protection; focus on fields such as big data, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, e-commerce, etc. |

| ASEAN | Emphasize long-term planning and clarify the establishment of the ASEAN Digital Economy Community by 2045 | Building a secure and robust digital governance framework that guarantees the rule of law; promote cross industry collaboration and multi-party sharing and co-construction; pursuing inclusive growth and digital equity |

| Ranking | Central Digital Economy Policies | Local Digital Economy Policies |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Smart Education | Smart Education |

| 2 | Smart Healthcare | Smart Healthcare |

| 3 | Internet-based Real Estate | Digital Culture and Tourism |

| 4 | Digital Capital Market Services | Environmental Management |

| 5 | Intelligent Transportation | Municipal Facility Management |

| 6 | Digitalized Facility Cultivation | Smart Warehousing |

| 7 | Smart Logistics | Specialized Equipment Manufacturing |

| 8 | Smart Warehousing | Smart Logistics |

| 9 | Digitalized Leasing | Digitalized Water Conservancy |

| 10 | Smart Agriculture | Digital Forestry |

| Sort | Shanghai | Beijing | Shenzhen | Chongqing | Guangzhou |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Big data center | Industrial internet | Industrial internet | Industrial internet | Industrial internet |

| 2 | Smart healthcare | Digital infrastructure | Big data center | Big data center | New infrastructure |

| 3 | Industrial internet | Network infrastructure | Information infrastructure | Information infrastructure | 5G base station |

| 4 | Smart education | Smart healthcare | Network infrastructure | Smart healthcare | Information infrastructure |

| 5 | New infrastructure | Smart education | Innovative infrastructure | 5G base station | Equipment manufacturing |

| 6 | Digital infrastructure | Digital culture and tourism | Communication network infrastructure | Innovative infrastructure | Integrated circuit design |

| 7 | Network infrastructure | Big data center | Digital infrastructure | Digital infrastructure | Smart healthcare |

| 8 | Information infrastructure | Information infrastructure | Smart healthcare | Smart education | Internet infrastructure |

| 9 | Transportation infrastructure | New infrastructure | Computing infrastructure | Integrated infrastructure | Smart education |

| 10 | Equipment manufacturing | Computing infrastructure | Equipment manufacturing | New infrastructure | Computing infrastructure |

| Type | Annual Differences in Policy Targets | Annual Differences in Policy Instruments | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Industrialization | Industrial Digitalization | Supply Oriented | Demand Oriented | Environment Oriented | ||||||

| Central | Local | Central | Local | Central | Local | Central | Local | Central | Local | |

| Z value | 0.92 | 2.49 *** | 1.90 ** | 2.75 *** | 11.98 *** | 18.99 *** | 11.50 *** | 24.11 *** | 16.84 *** | 32.36 *** |

| Period (year) | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Explanatory Variables | Policy Objectives | Policy Tools | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Keywords Related to Digital Industrialization | Number of Keywords Related to Industrial Digitalization | Number of Keywords Related to Supply Oriented Tools | Number of Keywords Related to Demand-Oriented Tools | Number of Keywords Related to Environment-Oriented Tools | |

| The proportion of the tertiary industry | 0.042 *** | 0.226 * | 0.008 ** | 0.007 | 0.003 ** |

| Fiscal revenue | 0.005 | 0.019 ** | 0.004 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.013 |

| Residents’ consumption level | 0.016 | 0.246 | 0.017** | 0.007 | 0.011 |

| Number of domestic invention patent applications accepted | 0.031 *** | 0.015 | 0.026 * | 0.011 * | 0.018 * |

| R&D funding | 0.006 ** | 0.001 * | 0.004 ** | 0.002 * | 0.002 ** |

| Number of samples | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 |

| R squared | 0.173 | 0.314 | 0.449 | 0.453 | 0.269 |

| Control variables | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Region fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Year fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, L.; Xiao, J.; Zuo, R. Research on the Evolution Characteristics of Policy System That Supports the Sustainability of Digital Economy: Text Analysis Based on China’s Digital Economy Policies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093876

Cai L, Xiao J, Zuo R. Research on the Evolution Characteristics of Policy System That Supports the Sustainability of Digital Economy: Text Analysis Based on China’s Digital Economy Policies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093876

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Li, Jianhua Xiao, and Renxian Zuo. 2025. "Research on the Evolution Characteristics of Policy System That Supports the Sustainability of Digital Economy: Text Analysis Based on China’s Digital Economy Policies" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093876

APA StyleCai, L., Xiao, J., & Zuo, R. (2025). Research on the Evolution Characteristics of Policy System That Supports the Sustainability of Digital Economy: Text Analysis Based on China’s Digital Economy Policies. Sustainability, 17(9), 3876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093876

_Li.png)