Abstract

This study proposes a design method for the evaluation and redesign of product–service systems (PSSs) from the perspective of social sustainability, one that applies Max-Neef’s framework of fundamental human needs. The proposed method systematically connects PSS functions and requirements—identified through service blueprints and value graphs—to “satisfiers” and “barriers” extracted via needs-based workshops. This connection enables the identification of functions that either contribute to or hinder the fulfillment of fundamental human needs and guide the generation of redesign proposals aimed at sufficiency-oriented outcomes. A case study involving a smart-cart system in Osaka, Japan, was conducted to demonstrate the applicability of the method. Through an online workshop, satisfiers and barriers related to both physical and online shopping experiences were identified. The analysis revealed that existing functions such as promotional information and automated checkout processes negatively impacted needs such as understanding and affection due to information overload and reduced human interaction. In response, redesign concepts were developed, including filtering options for information, product background storytelling, and optional slower checkout lanes with human assistants. The redesigned functions contribute to the fulfillment of fundamental human needs, indicating that the proposed method can enhance social sustainability in PSS design. This study offers a novel framework that extends beyond traditional customer requirement-based approaches by explicitly incorporating human needs into function-level redesign.

1. Introduction

One of the UN Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015 is the realization of sustainable consumption and production (SCP). This is a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity [1,2]. The achievement of SCP patterns requires not only improving environmental sustainability by reducing environmental loads and resource consumption, but also improving the sufficiency of SCP for satisfying fundamental human needs and enhancing social sustainability. This means that an approach is needed that takes into account not only the production side but also the consumption side to achieve SCP patterns [3].

On the production side, product and service design has been studied mainly in the areas of circular economy [4,5] and eco-design, with a focus on environmental sustainability [6,7,8]. On the consumption side, there have been several studies on business models and consumer behavior, generally with a focus on environmental sustainability [9,10,11], and social sustainability [12,13]. However, there are few studies on product and service design that consider social sustainability [14,15].

In the field of product and service design, many design methodologies have been proposed for the design of functions based on requirements in product design [16,17,18,19] and service design [20,21]. Similarly, requirements-based design methodologies have been proposed [22,23], but almost no product and service design methodologies have been studied from the viewpoint of sufficiency for consumers.

To achieve SCP, it is important to improve sufficiency for consumers; this can be achieved in the context of fewer products and services, and for this purpose, a design method aiming to provide highly sufficient products and services is necessary. However, in most cases, sufficiency is evaluated at the global level [24,25], or national level [26,27], and there are few methods available for evaluating sufficiency at the product or service level. Moreover, even if sufficiency could be evaluated at the product or service level, it is not clear how to design products and services to improve sufficiency.

Focusing on the regionality of consumer sufficiency, there have been several studies using the human scale development (HSD) approach proposed by Max-Neef [28,29,30]. The HSD framework is widely referenced in the field of sustainable consumption, particularly in discussions of social sustainability, where it is frequently cited alongside Doyal and Gough’s theory of human need [31]. In recent years, the HSD approach has also been applied in studies on the circular economy to evaluate social sustainability and its relationship to the fulfillment of human needs [32,33]. There have also been efforts to apply the HSD approach to product and service design. For example, Kobayashi and Fukushige proposed the living-sphere approach as a specific product design approach for locally oriented sustainable design [34]. The living-sphere approach is characterized by incorporating Max-Neef’s fundamental human needs framework into the evaluation of the sufficiency of products and services, with the goal of designing highly sufficient products and services based on the relationship between fundamental human needs and products/services.

In this study, we aim to contribute to social sustainability in sustainable consumption by designing products and services that help fulfill Max-Neef’s description of fundamental human needs. Specifically, we seek to operationalize the conceptual structure of the living-sphere approach and propose a needs-based design method for product–service systems (PSSs) based on it. To demonstrate the applicability of the proposed method, a case study was conducted on a smart-cart system implemented in Osaka, Japan. The aim of the case study was to examine how the method can be used to identify functions that promote or hinder the fulfillment of fundamental human needs, and to propose redesign ideas that enhance social sustainability in PSS design. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review related works on HSD, and product and service design. Section 3 outlines our proposed needs-based PSS design method, and Section 4 shows a case study of its application to a smart cart. Section 5 discusses the proposed method and the case study, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Human-Scale Development and Its Applications

To help groups or communities engage in the process of change and development, Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef proposed the HSD approach [28,35]. HSD has three main pillars: (1) the satisfaction of fundamental human needs, (2) the generation of growing levels of self-reliance, and (3) the construction of organic articulations associating people with nature and technology, global processes with local activity, the personal with the social, planning with autonomy, and civil society with the state.

In HSD, fundamental human needs are the same in all cultures and historical periods, changing only at a very slow pace according to our evolution as a species; satisfiers are the values, attitudes, norms, laws, institutional arrangements, organizations, actions, and ways of using spaces, resources, and nature that define needs satisfaction in specific contexts, and which vary across cultures and through time [36,37]. Max-Neef organized fundamental human needs into two categories: axiological and existential. The axiological category includes subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, idleness, creation, identity, and freedom. The existential category includes being, having, doing, and interacting. Table 1 shows a matrix that relates axiological and existential categories, and within which the individual cells represent satisfiers. Max-Neef also proposed a workshop method to construct not only a matrix of positive satisfiers (those that contribute need fulfillment), but also a matrix of destructive elements—referred to as negative satisfiers—that hinder need fulfillment within a society [37,38,39]. For example, Kobayashi et al. introduced the term barriers to refer to these negative satisfiers in order to clearly distinguish them from positive ones [39]. Following this approach, in this paper we refer to positive satisfiers simply as “satisfiers”, and to negative satisfiers as “barriers”. We adopt this terminology throughout the manuscript for consistency and clarity.

Table 1.

Matrix of fundamental human needs.

While most of the applications of the HSD framework have aimed to identify community issues and propose solutions, a few cases have applied the HSD framework to evaluate services. Gimelli et al. analyzed how water service arrangements can hinder or contribute to the satisfaction of the whole range of fundamental human needs in an urban informal settlement by conducting semi-structured, in-depth individual interviews and informal individual and group discussions including 29 participants aged 18 years or older (in India) [40]. Jolibert et al. analyzed the causes of conflict over the Sado River in Portugal by extracting the satisfiers of fish farmers, reserve managers, and otters, who are stakeholders in the river, through semi-structured interviews and a literature review [30]. The commonality among them is the application of the HSD framework to the sufficiency assessment of services provided in the community.

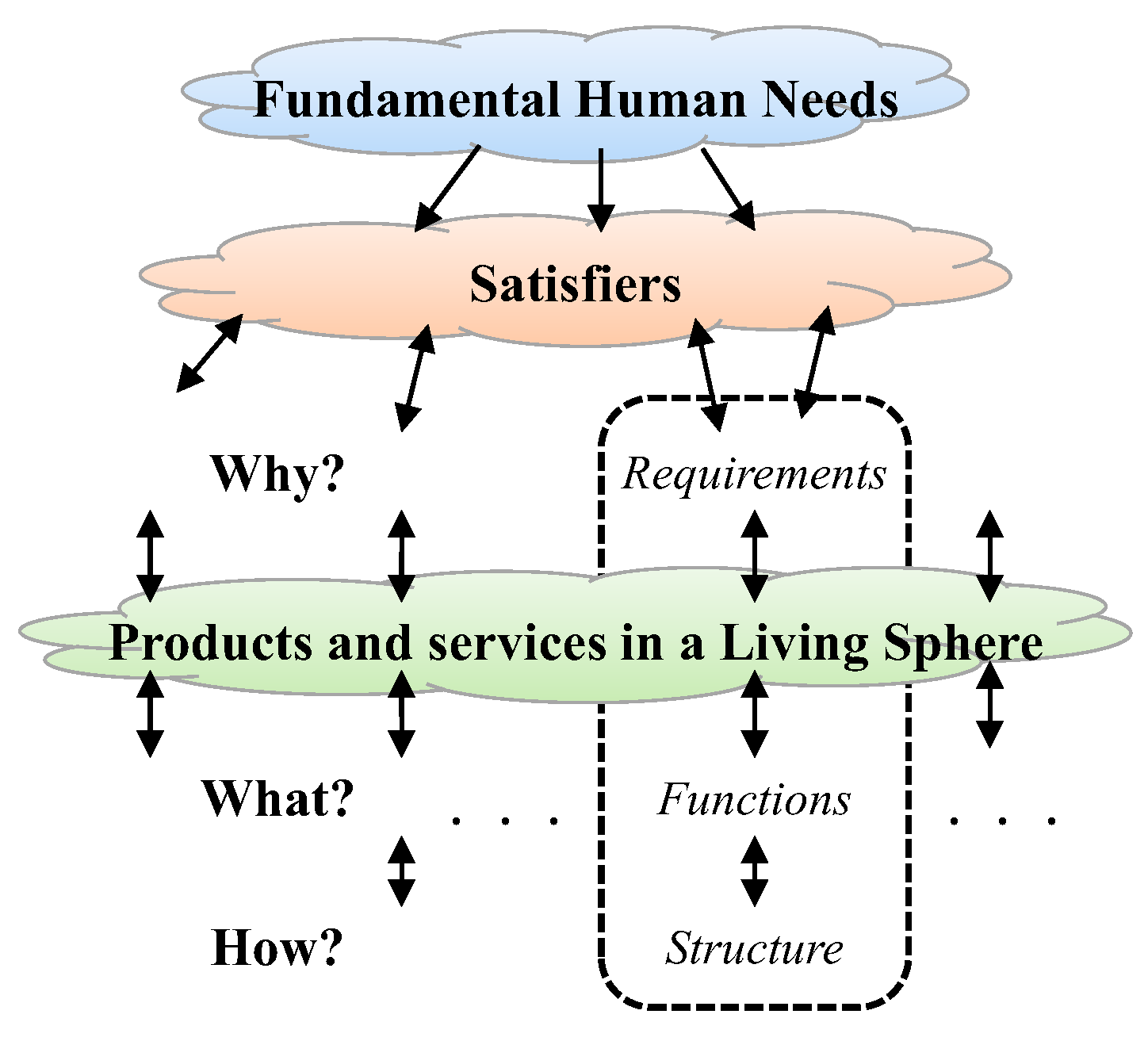

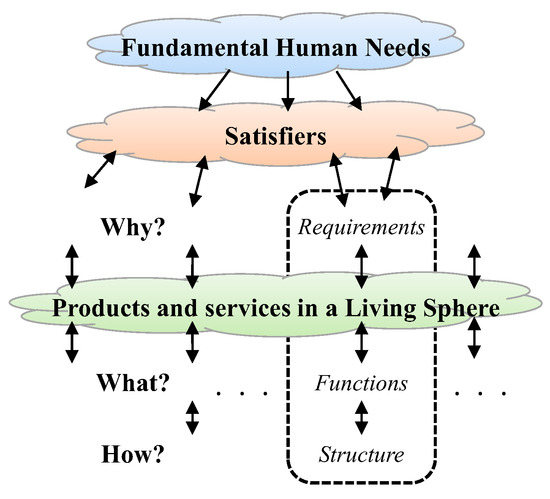

The living-sphere approach has also been proposed as an attempt to apply the HSD framework to product design [34] (Figure 1). In this approach, it is assumed that fundamental human needs are fulfilled by activating the satisfiers. Many products are connected to satisfiers in the framework of the living-sphere approach. Therefore, extracting adequate satisfiers is a key task in the living-sphere approach. Examples of the application of this approach include the modeling of the relationship between a product and relevant satisfiers through its functions and requirements, and an evaluation of bathroom design in Vietnam using satisfiers as evaluation criteria [41,42]. However, there are no examples of HSD being applied to the designs of products or services.

Figure 1.

Concept of the living-sphere approach.

2.2. Product and Service Design

Engineering design methods generally produce design details in a top-down process, starting from the product requirements, and then considering the designs of functions, and then structures [16,17]. For example, in function structure mapping [43], structures are designed from functions, and in value graphs and quality function deployment (QFD) [44,45], functions and structures are designed from requirements. In systems engineering, first, the boundary of the target system to be designed is defined; this is followed by a requirements analysis, and then the architecture design [18,19]. In requirements analysis, stakeholders are identified and requirements are detailed. In architectural design, the functional architecture is first designed based on the requirements; this is followed by a design of the physical architecture that assigns functions to hardware and software [19].

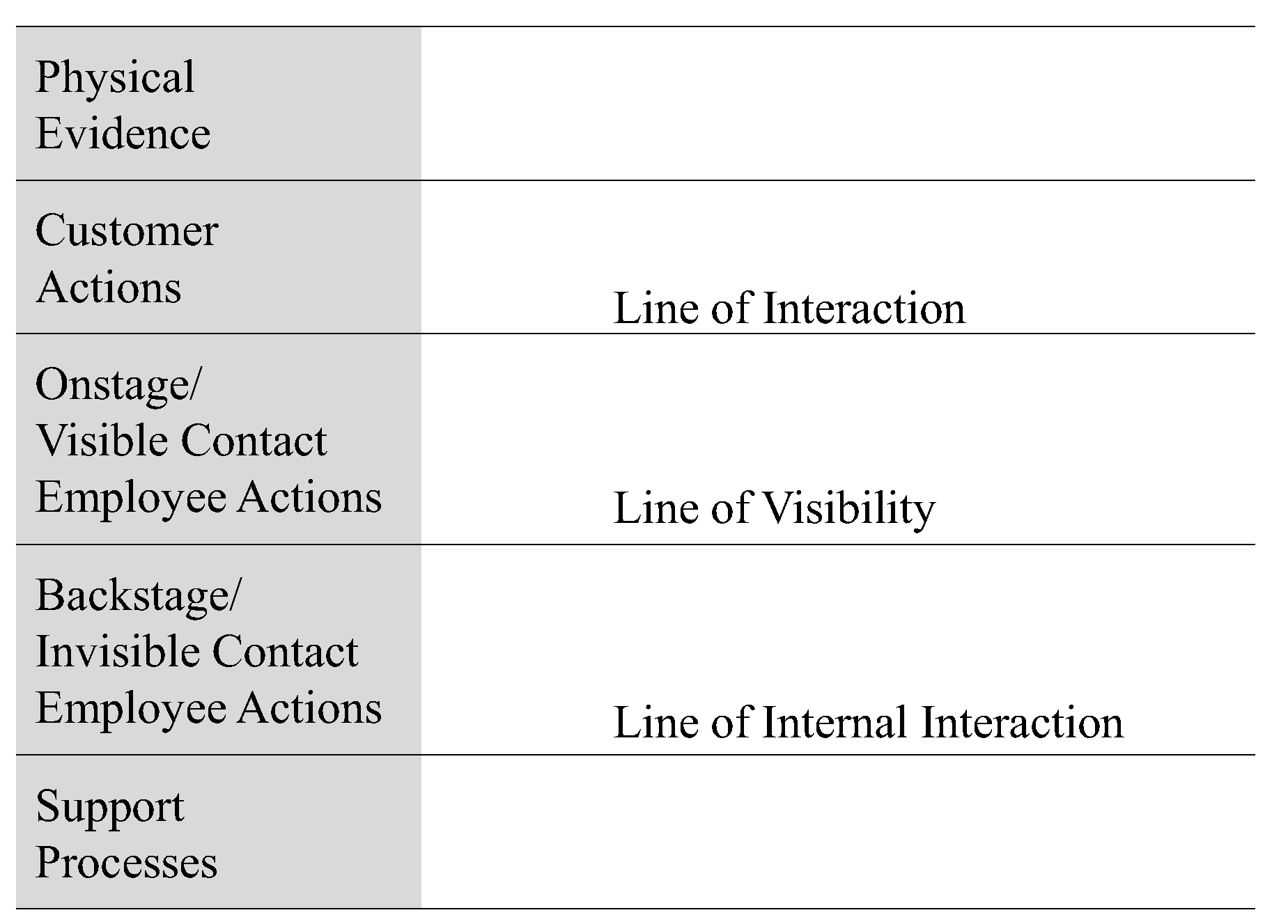

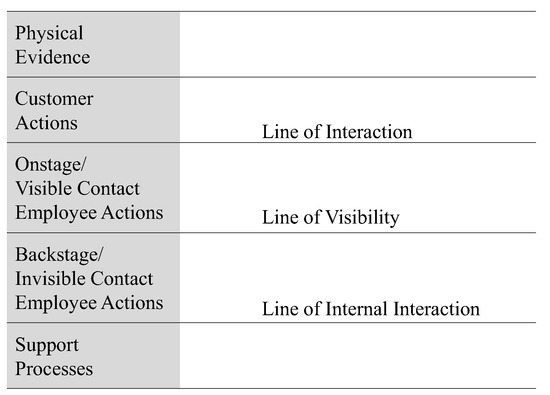

Service design has been extensively studied in the marketing and engineering fields. Various service design methods have been proposed; one common process consists of designing services and products based on customer requirements [20,46]. In particular, a marketable set of products and services capable of jointly fulfilling users’ requirements is called a PSS [47], and there has been a shift from service design to PSS design. Various methods have been proposed for service design and PSS design [23,48,49], but one of the most commonly used methods is service blueprints [22,50]. Service blueprints are used to clarify the functions of the services and products needed to fulfill customer requirements, and can model the functions of involved stakeholders separately. Although there are no fixed rules for representation, a typical service blueprint includes five elements, as shown in Figure 2: customer actions, onstage/visible contact employee actions, backstage/invisible contact employee actions, support processes, and physical evidence [50]. In the field of PSS design, extensions of service blueprints to PSS and EcoDesign [51,52], as well as PSS design frameworks incorporating service blueprints, have been proposed [21].

Figure 2.

Components included in a typical service blueprint.

As described above, existing methodologies in product and service design focus primarily on deriving product or service functions from product and customer requirements, whether through top-down engineering approaches or structured service design frameworks. While these methods are effective in designing products and services based on customer requirements that have been identified, they do not explicitly consider the broader and more socially grounded concept of fundamental human needs. Moreover, these methods typically lack mechanisms to evaluate how design elements may contribute positively or negatively to human well-being—what Max-Neef refers to as satisfiers/barriers.

Although some approaches attempt to explain customer requirements by referring to psychological theories such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, this model has been widely criticized. Maslow himself later acknowledged that the hierarchical nature of needs was not universally applicable [53]. Furthermore, scholars have argued that the model reflects individualistic and Western cultural assumptions that may not be suitable for societies that prioritize social or collective needs over individual self-actualization [54,55]. In contrast, Max-Neef’s framework proposes a culturally neutral, non-hierarchical view in which all fundamental human needs are equally important and can be fulfilled simultaneously. This framework allows for a more inclusive and socially responsive interpretation of customer requirements.

As a result, conventional design approaches may overlook important aspects related to sufficiency and social sustainability in design outcomes. This gap calls for a new approach that incorporates these overlooked dimensions in the design of products and services.

3. Needs-Based Design Method for Product–Service Systems

3.1. Concept

To address both product and service aspects, this study focuses on PSSs. The living-sphere approach illustrated in Figure 1 shows the relationships between fundamental human needs and satisfiers/barriers, satisfiers/barriers and requirements, requirements and functions, and functions and structures. The relationships between fundamental human needs and satisfiers/barriers have been clarified in the HSD framework, while those between requirements and functions, and between functions and structures, have been clarified in the field of engineering design. However, the relationships between satisfiers/barriers and requirements are not yet clear.

According to Max-Neef, satisfiers and barriers do not refer to available economic goods, such as products or services, but rather to economic goods that empower satisfiers to meet fundamental human needs fully and consistently [28]. Therefore, in this study, satisfiers and barriers are regarded as concepts that are more abstract than the requirements for products and services. Based on this understanding, we attempt to connect these abstract elements to conventional design concepts by associating satisfiers and barriers with requirements, and further linking them to functions using design methods such as value graphs and service blueprints.

In addition, because the structures of a PSS are determined under various constraints, this study covers the functional design of a PSS and does not cover the assignments of functions to structures. A model that connects functions and requirements to satisfiers/barriers is constructed in a bottom-up manner. Functions are first extracted using a service blueprint, and the corresponding requirements are then derived through a value graph by repeatedly asking why each function is needed. These requirements are subsequently connected to the satisfiers/barriers identified through needs-based workshops.

This modeling process enables the designer to understand how each function contributes to or inhibits the fulfillment of fundamental human needs. As a result, the proposed method provides an integrative framework that supports sufficiency-oriented design by incorporating social sustainability considerations into conventional product and service design.

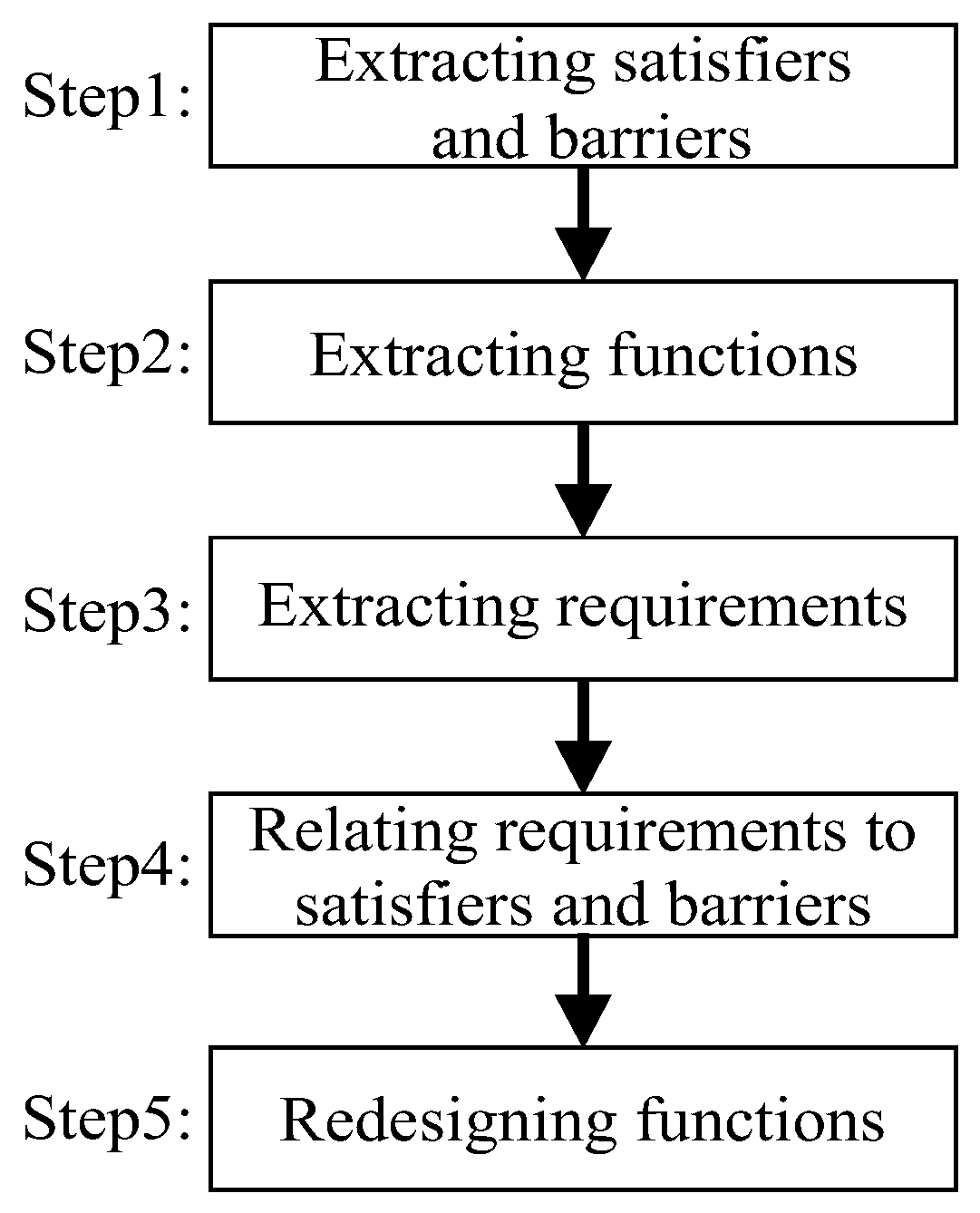

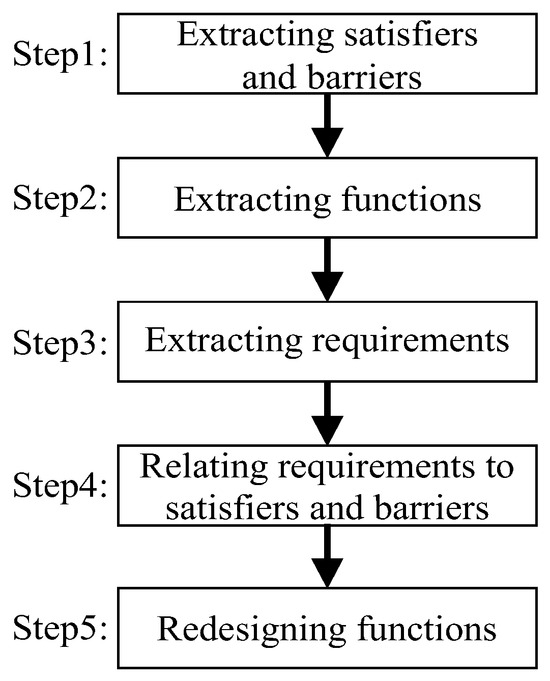

3.2. Procedure

Figure 3 shows the procedure of the needs-based redesign method. To redesign an existing product to improve its sufficiency, this method first analyzes the existing product, and then models its relationship with satisfiers/barriers and redesigns its functions. The following illustration explains each step of the procedure.

Figure 3.

Procedure associated with the needs-based redesign method.

3.2.1. Step 1: Extracting Satisfiers and Barriers

Satisfiers and barriers can be extracted through needs-based workshops [37,38], interviews [30,40], and literature reviews [32,56]. In this study, workshops were adopted for two reasons. The first is that interviews and literature reviews require post-processing, which may introduce the designer’s intention into the analysis. The second is that the authors have held needs-based workshops several times, both in person and online [39,57].

The needs-based workshop proposed by Max-Neef is a 2-day workshop with 50 participants, but this has been difficult to organize and implement in recent years owing to the amount of funds and time required for the exercise. For this reason, various shorter workshops with smaller numbers of participants have been proposed [58]. Kobayashi et al. proposed a 5 h workshop with about 20 participants [39]. This method was modified by Murata et al. such that workshops could be conducted online by combining multiple digital tools [57]. In this study, we employed the workshop method proposed by Kobayashi et al. for in-person sessions and the that proposed by Murata et al. for online sessions [39,57].

3.2.2. Step 2: Extracting Functions

The functions of a PSS include both product functions and service functions, and services have a variety of stakeholders. Therefore, in Step 2, a service blueprint is used to analyze the product and service functions separately for each stakeholder.

3.2.3. Step 3: Extracting Requirements

In Step 3, a value graph is used to extract the requirements of the target PSS by asking the designer why the function is required for each function [44].

3.2.4. Step 4: Relating Requirements to Satisfiers and Barriers

Paired comparisons of the requirements and satisfiers/barriers are performed, and if it is judged by the designer that a relationship may exist between them, the requirements and satisfiers/barriers are connected. Although this step is intended to be performed by a designer, verification by multiple persons is recommended, because the connection decisions depend on the designer’s judgement.

3.2.5. Step 5: Redesigning Functions

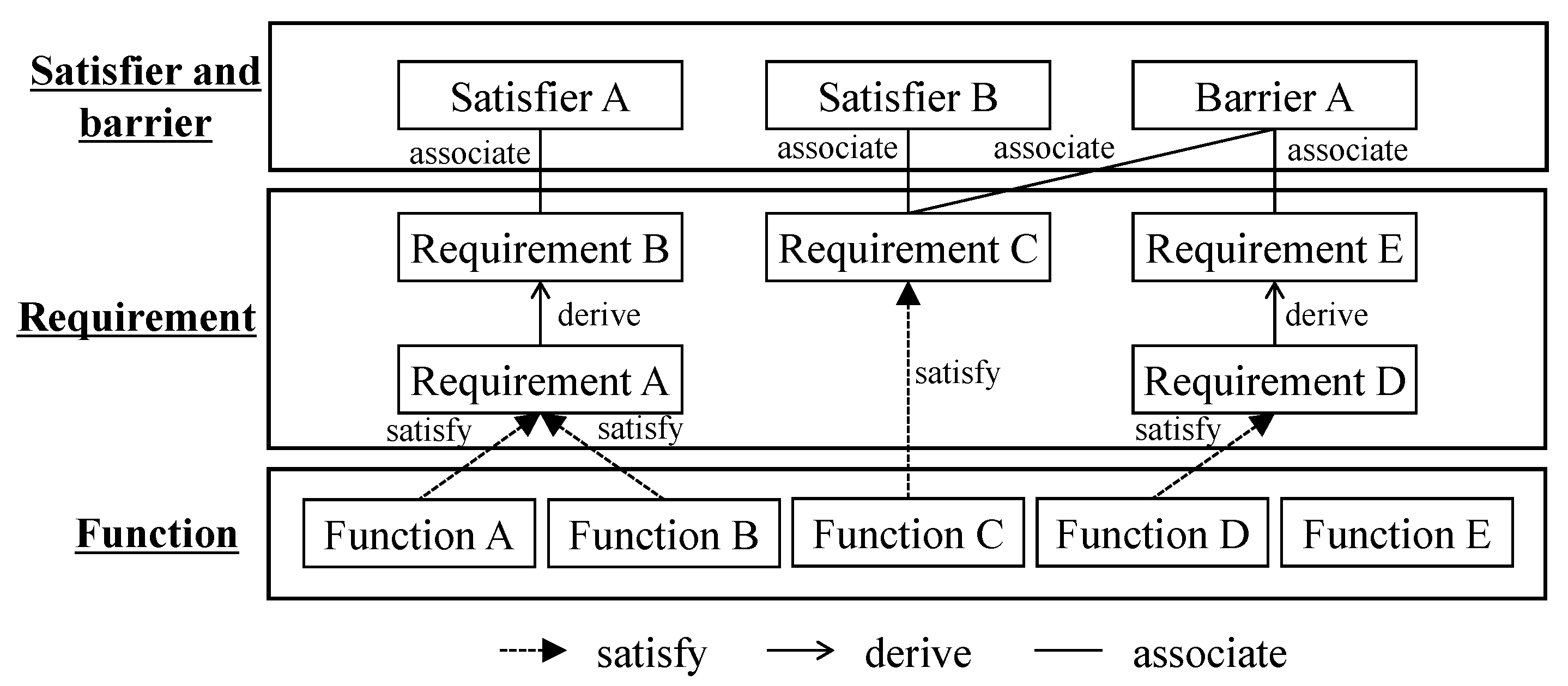

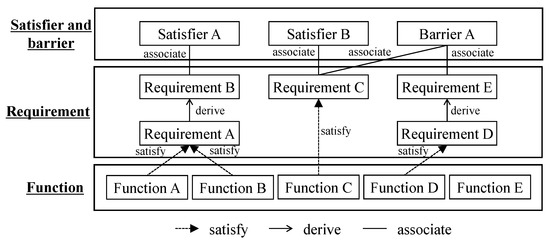

Figure 4 shows an overview of the model constructed in Steps 1 to 4. In Step 5, the functions are redesigned in order to improve the sufficiency, based on the model.

Figure 4.

Conceptual model for the connection of functions to satisfiers and barriers.

To fulfill fundamental human needs, it is necessary to realize satisfiers and to prevent the realization of barriers. The following three methods can be suggested for the redesign of functions to improve sufficiency.

- (1)

- Modify or remove functions that connect only to barriers;

- (2)

- Separate or modify functions that connect to both satisfiers and barriers;

- (3)

- Add functions that can realize satisfiers that have not been realized by existing functions.

In the next section, we describe the results achieved when applying the proposed method to smart carts.

4. Case Study: Needs-Based Functional Redesign of Smart Carts

4.1. Design Target

With the progress of digitalization in the retail industry, new services such as cashless payment and e-commerce sites are becoming more widespread. Another such service is smart carts, which are shopping carts equipped with a scanner for reading barcodes and a tablet terminal for displaying information; these have been recently introduced as a new checkout system in some supermarkets. Figure 5 shows the appearance of a smart cart used in Japan. Smart carts are coming into wider use, but what motivates customers to accept smart carts is not clear.

Figure 5.

A smart cart used in Japan.

In this case study, we clarified which functions of smart carts contribute to their adoption by analyzing which functions of the smart carts realize the satisfiers of customers or prevent the realization of barriers.

4.2. Application of the Proposed Method to a Smart Cart

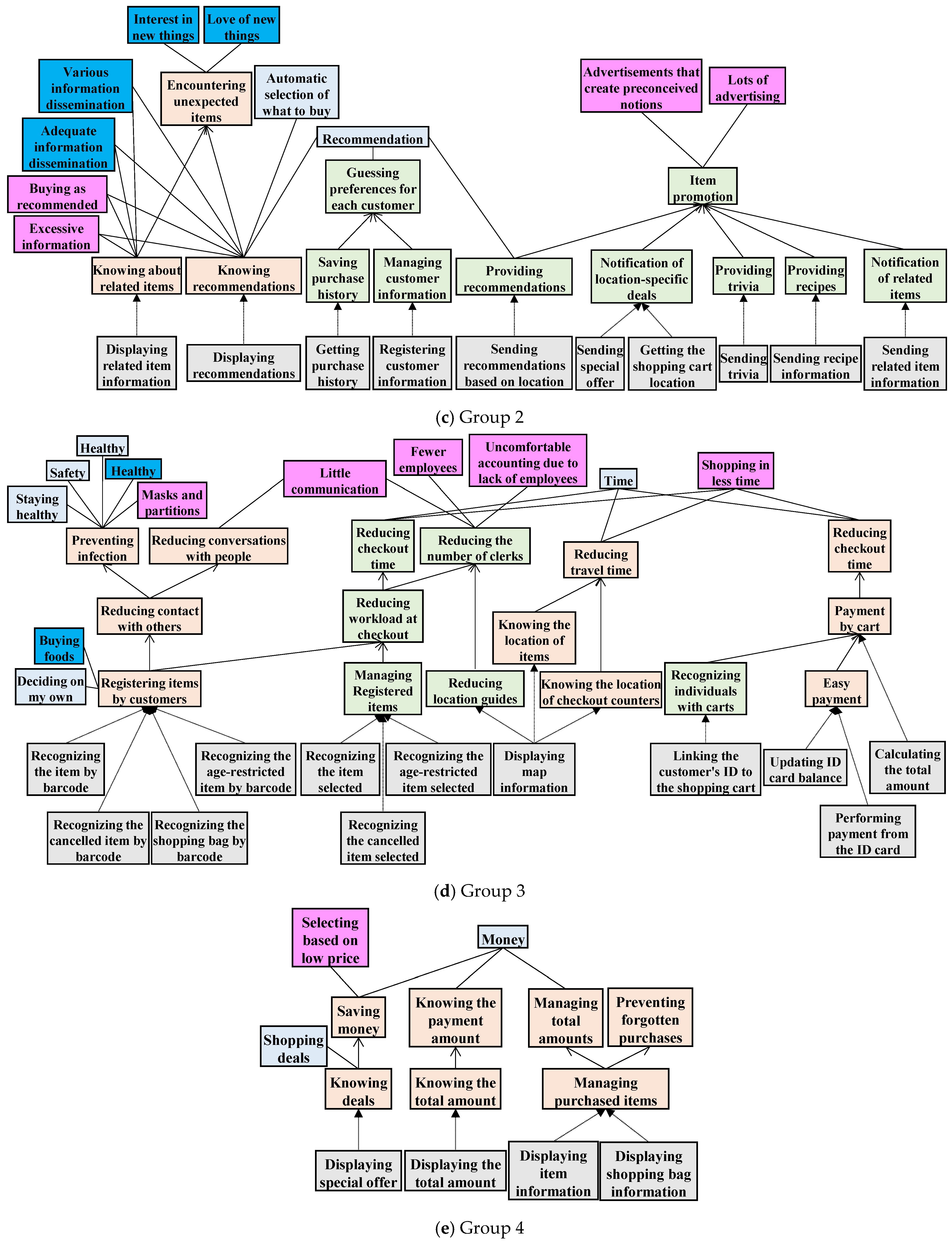

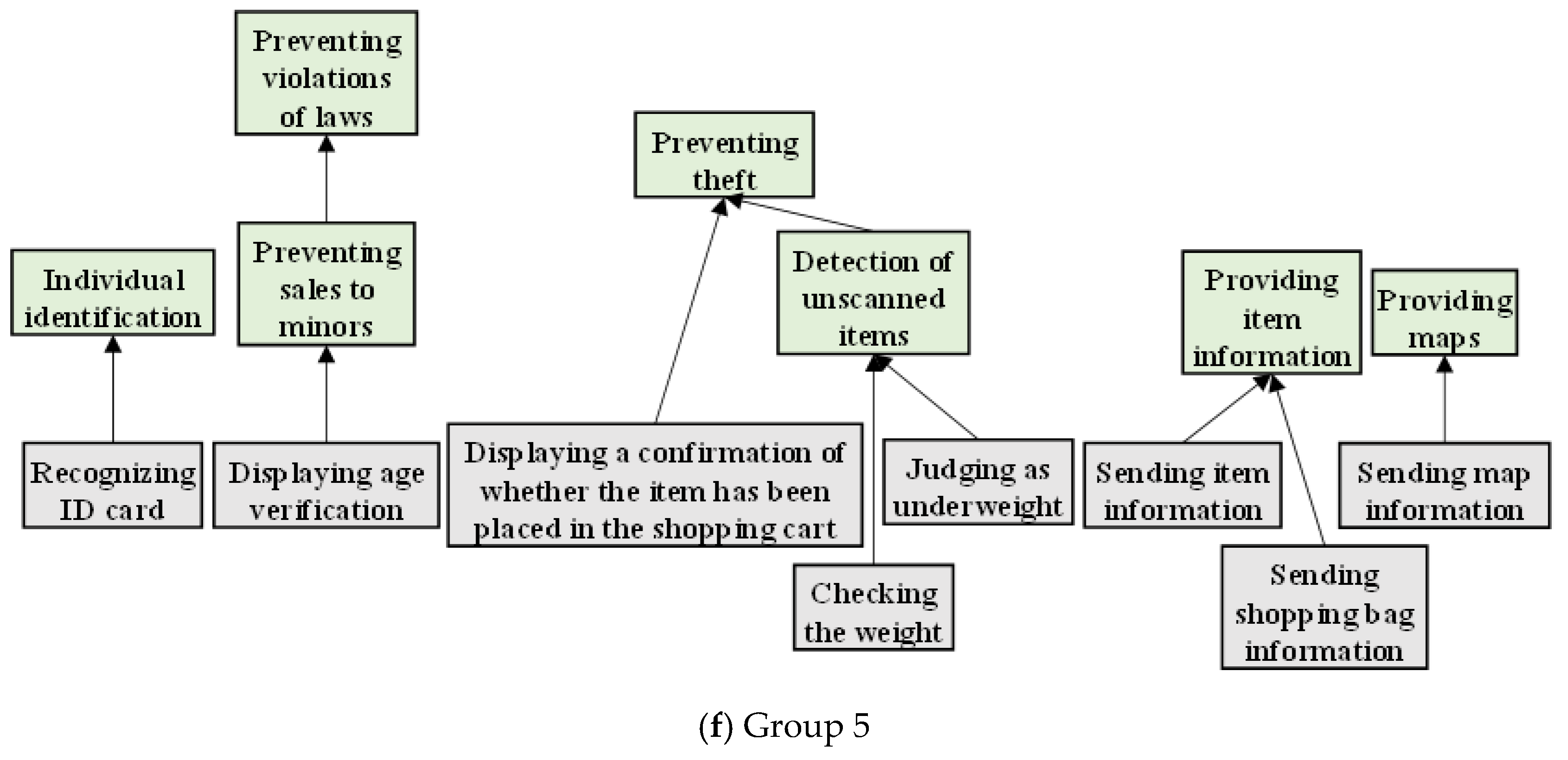

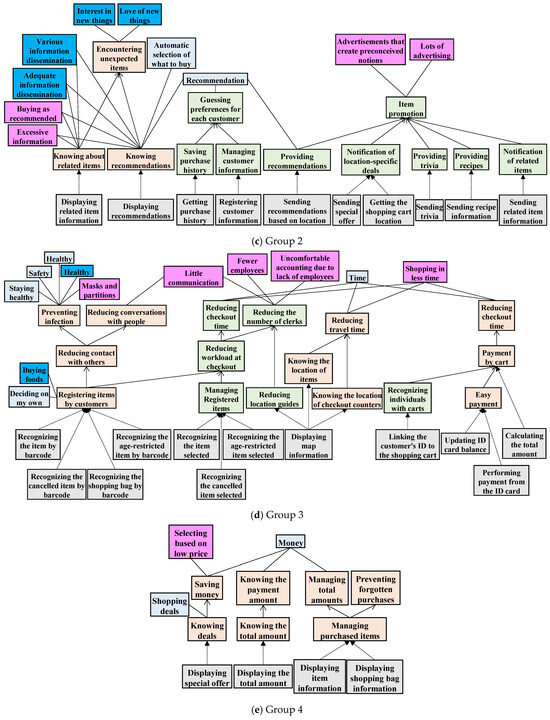

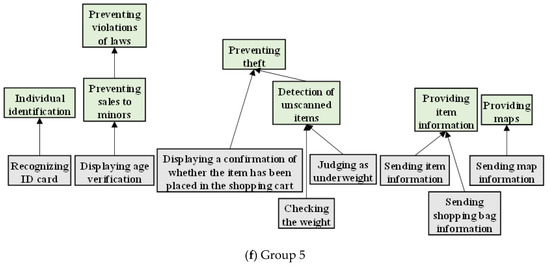

4.2.1. Step 1: Extracting Satisfiers and Barriers

The needs-based workshop aimed to extract satisfiers and barriers in the context of a supermarket. The workshop was held online in November 2021. The workshop participants ranged from people in their 20s to people in their 60s, and were grouped according to whether they were frequent users of physical stores or online stores. The reason for creating these two groups was that smart carts have both the functions of physical stores (e.g., users can physically select and purchase products) and those of online stores (e.g., customer purchase data can be managed and users may be presented with various types of information).

Table 2 shows the members of each group in the needs-based workshops. There was much input from frequent users of physical stores, so one satisfier group and two barrier groups were created for physical stores. However, there were few responses from frequent users of online stores, so only one satisfier group, and no barrier group, was created for online stores. Table A1 and Table A2 show the extracted satisfiers and barriers, respectively, for physical stores, and Table A3 shows the satisfiers for online stores. The satisfiers and barriers shown in these tables met the following two conditions: the majority of the group participants agreed with their assignment, and the participants’ assumptions are correct.

Table 2.

Members of each group in the needs-based workshops.

One example of an incorrect satisfier was the inclusion of “online supermarket” in the satisfier group for physical stores—this should instead be considered as an online-store satisfier. One example of an incorrect barrier was the inclusion of “not wearing a suit” in the barrier group for physical stores—in this case, a participant stated that “not wearing a suit makes it difficult to enter a store that would have a dress code”; it was determined that the participant did not assume the context of a supermarket.

4.2.2. Step 2: Extracting Functions

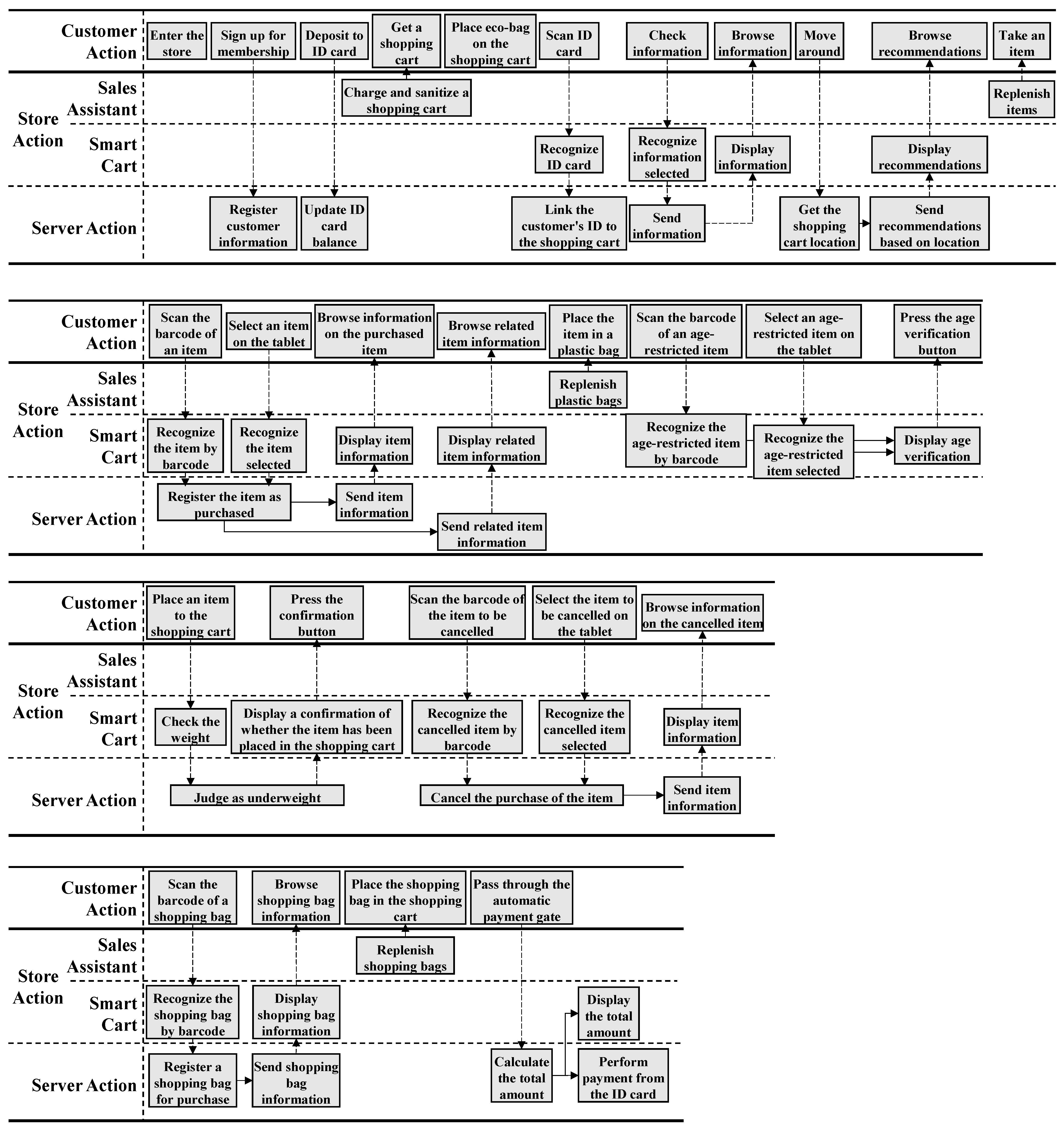

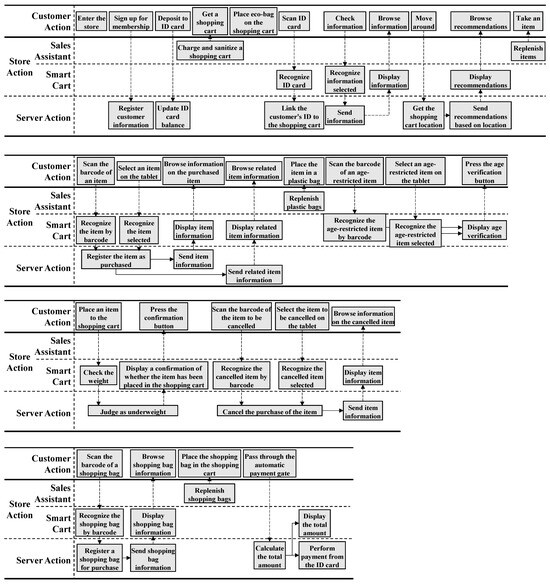

Smart carts allow customers to perform several actions using the cart itself, the tablet, and the scanner, and these actions are realized by the functionality of the smart-cart equipment as well as a server on the backend. Figure 6 shows the service blueprint of the smart cart. The service blueprint was created with reference to the shopping experience, using the smart cart and information published by companies that have developed or introduced smart carts. Because the smart cart is used from the point of entry to the point of payment, the customer actions are also described as well.

Figure 6.

Service blueprint for a smart cart.

Table 3 lists the functions of the smart cart. Although Figure 6 describes the function of the sales assistant, the sales assistant is not mentioned in Table 3 because the sales assistant is considered to belong to the supermarket, not to the smart cart. Specifically, the sales assistant performs store-level maintenance tasks, such as shelf restocking, bag replenishment, and cart disinfection, which support overall operations but do not directly influence the customer’s purchasing experience. Therefore, this role is excluded from the functional analysis in this study, which focuses on the functions that constitute the smart cart-based service system from the customer’s perspective.

Table 3.

List of smart-cart and server functions.

“Send information”, the action of the server in Figure 6, is separated into the functions “sending special offer”, “sending map information”, “sending purchase history”, “sending trivia”, and “sending recipe information” in Table 3. Similarly, “display information”, the action of the smart cart, is separated into the corresponding functions “displaying special offer”, “displaying map information”, “displaying purchase history”, “displaying trivia”, and “displaying recipe information” in Table 3.

4.2.3. Step 3: Extracting Requirements

The requirements of the smart cart were extracted by repeatedly questioning why the function would be required for the customer and why the function would be required for the store for each function. The reason for targeting both customers and stores is that the smart cart realizes not only customer requirements but also the requirements of the store, such as the management of customer and product information.

4.2.4. Step 4: Relating Requirements to Satisfiers and Barriers

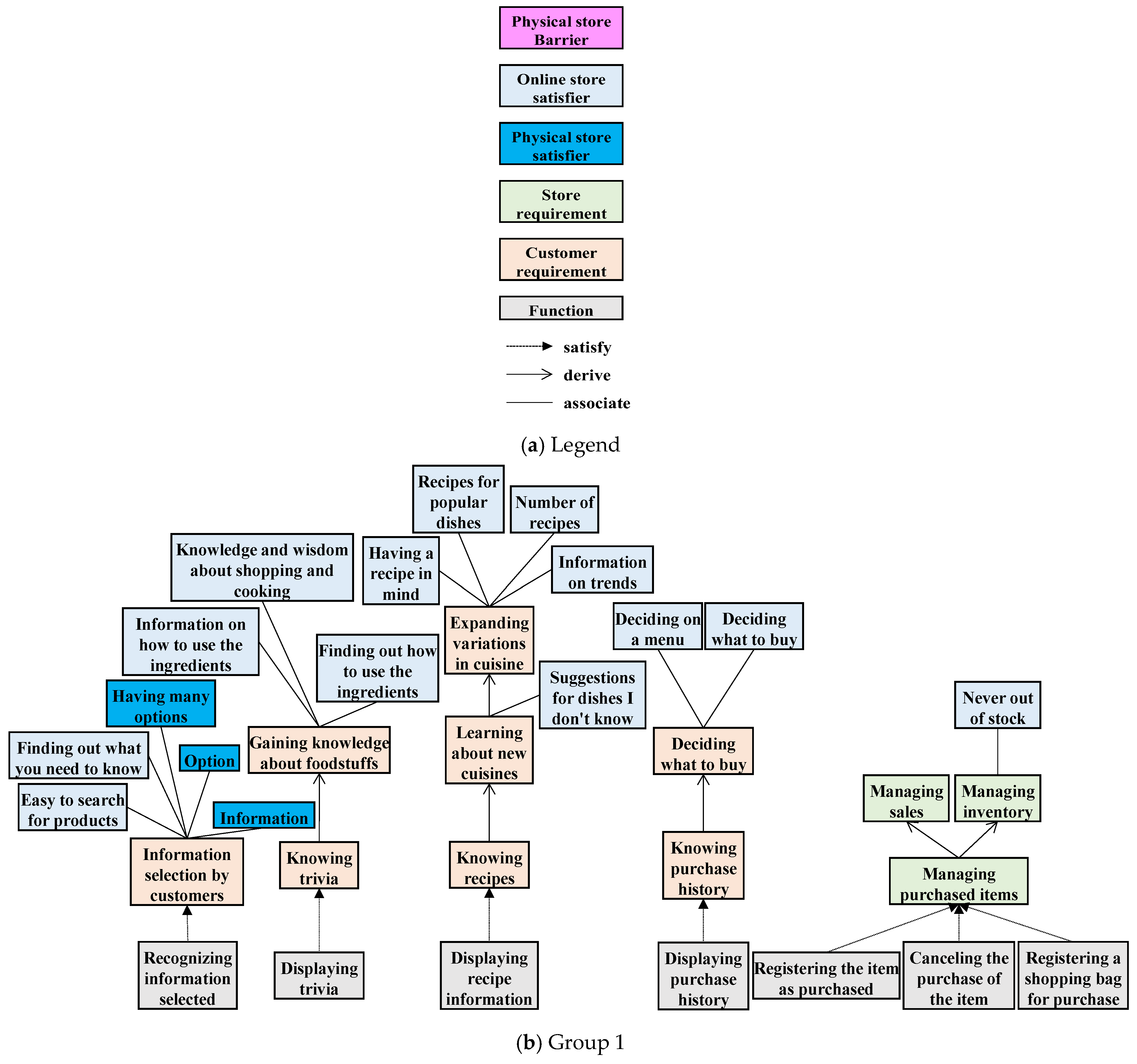

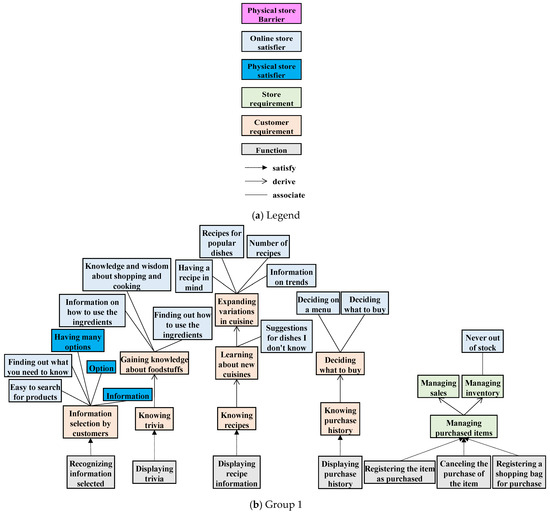

A paired comparison was made between the requirements extracted in Step 3 and the satisfiers and barriers in physical stores, in addition to the satisfiers in online stores described in Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3. Figure 7 shows the connections between the functions and requirements and the satisfiers/barriers in the smart-cart model.

Figure 7.

Connections between the functions and requirements and the satisfiers/barriers in the smart-cart model.

In Figure 7, requirements are grouped not by the nature of the functions themselves, but as based on the types of satisfiers or barriers they are associated with. This classification was applied post hoc, after the paired comparison, to clarify how different functions promoted or hindered the fulfillment of fundamental human needs. The grouping does not reflect functional categories but rather highlights the relationships between customer requirements and satisfiers/barriers, as identified in the Max-Neef framework.

The model reveals several functions that contribute to the realization of satisfiers. Figure 7b shows the functions connected only to satisfiers. For example, the smart-cart function, “recognizing information selected” is connected via the customer requirement “information selection by customers” to multiple satisfiers associated with both physical and online stores, such as “option” and “easy to search for products”, and can be judged to be a function that is important for customer sufficiency. Other smart-cart functions related to displaying information, such as “displaying trivia”, “displaying recipe information”, and “displaying purchase history”, are also connected only to satisfiers, indicating that these smart-cart-specific functions contribute to the sufficiency for customers. This suggests that being able to access relevant information and purchase history while shopping with the smart cart significantly contributes to human-need fulfillment, which may be a factor in the adoption of smart carts. Meanwhile, Figure 7c shows that the server functions “sending trivia” and “sending recipe information” are connected to multiple barriers via the store requirement “item promotion.” It is likely that customers will experience decreased sufficiency if they perceive promotional intent in the trivia or recipe information displayed. In other aspects, payment functions in the smart cart, such as “recognizing items by barcode” and “recognizing cancelled items by barcode” as described in Figure 7d, are connected to the satisfiers associated with both physical and online stores, while “reducing the number of sales assistants”, the store requirement connected to them, is connected to multiple barriers. This suggests that even though the smart cart is able to accept payment, the resulting reduction in sales assistants would reduce sufficiency for customers. This indicates that the smart cart not only has functions that improve sufficiency, but also has functions that may reduce sufficiency, and this may be why smart carts are being gradually adopted, rather than experiencing explosive growth.

In the next step, we describe the results of redesigning the functions of the smart cart to improve sufficiency for customers.

4.2.5. Step 5: Redesigning Functions

The functions were redesigned using the three methods given in Step 5 of Section 3.2. The results for each method are described below.

(1) Modify or remove functions that connect only to barriers.

In Figure 7c, the store requirement “item promotion” is connected to the barriers “advertisements that create preconceived notions” and “lots of advertising”, and “item promotion” is also connected to the server functions “sending recommendations based on location”, “sending special offers”, “retrieving shopping cart location”, “sending trivia”, “sending recipe information”, and “sending related item information.” Among these functions, “send recommendations based on location” is connected to the satisfier “recommendations” via the store requirement “providing recommendations”, while “sending special offers”, “retrieving shopping cart location”, “sending trivia”, “sending recipe information”, and “sending related item information” are connected only to barriers. Therefore, it is recommended that these five server functions be modified or removed.

Meanwhile, the service blueprint shows that the server action “send information” realizes the smart-cart action “display information.” This means that the server functions “sending special offers”, “sending trivia”, and “sending recipe information” are necessary to realize the smart-cart function “displaying special offers” in Figure 7e and the smart-cart functions “displaying trivia” and “displaying recipe information” in Figure 7b. Because these functions are connected to satisfiers, they should be retained. Similarly, the server function “sending related item information” is necessary to realize the smart-cart function “displaying related item information” in Figure 7c, and the server function “getting the shopping cart location” is necessary to realize the server function “sending recommendations based on location” in Figure 7c. In these cases, it is recommended that the function be modified so that the barriers are not realized. For example, it is suggested that the types and numbers of advertisements be adjusted so that preconceived notions are not created.

(2) Separate or modify functions that connect to both satisfiers and barriers.

Figure 7c–e shows the functions that are connected to both satisfiers and barriers. These functions should be separated or modified to remove requirements that lead to the realization of barriers. For example, the smart-cart function “displaying related item information” is connected to the satisfiers “dissemination of various information”, “dissemination of adequate information”, “interest in new things”, and “love of new things” via the customer requirements, while it is connected to the barriers “buying as recommended” and “excessive information” in Figure 7c. This can be interpreted as a case in which the related-item information can be perceived either favorably or negatively. To address this problem, a button should be implemented which would allow customers to choose whether to display the related-item information. Alternatively, if the type of related-item information provided is interpreted to be a problem, buttons that allow customers to choose whether to display the related-item information for each information category might be proposed.

In Figure 7d, smart-cart functions such as “recognizing items by barcode”, which are connected to the customer requirement “registering items by customers”, are connected to the satisfier “time” and the barriers “little communication” and “fewer employees”, because the smart cart can recognize items by their barcodes, which reduces the number of sales assistants at the checkout counter. In this case, it is suggested that the payment function be divided into two types: one for those who want to save time and the other for those who want to communicate with others. For example, a combination of both smart-cart payment and chat lanes, as has been introduced in the Netherlands and some areas of Japan, could be used. Chat lanes are traditional checkout lanes but with a slower checkout process, designed for the purpose of talking with the checkout sales assistants.

(3) Add functions that can realize satisfiers that have not been realized by existing functions.

Additionally, functions need to be added to smart carts that realize satisfiers not currently connected to existing functions. For example, the physical-store satisfier “feeling the love of the producers” and the online-store satisfiers “producer information” and “knowing the story of products” can be realized by adding a function to display some background information relating to the items. Also, the online-store satisfiers “food preferences in the family” and “ingredient allergies” could be realized by adding functions to register the likes and dislikes of customers and allergy information and to display them when purchasing foods.

To clarify the relationship between the identified issues and the proposed redesign, Table 4 summarizes how each redesign function addresses specific barriers or enhances satisfiers, ultimately contributing to the fulfillment of fundamental human needs.

Table 4.

Functional redesign summary with corresponding barriers, satisfiers, and fundamental human needs.

These redesign elements are derived from the structured analysis of satisfiers and barriers in the previous steps and reflect a deliberate effort to improve the fulfillment of fundamental human needs. By aligning functional design with fundamental human needs, the smart cart can be better positioned to support users, not only in practical terms but also in ways that resonate with broader social sustainability.

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the proposed model in which functions, requirements and satisfiers/barriers are connected, the method of redesigning functions based on the model, and the needs-based workshop in the context of a supermarket.

5.1. Effectiveness and Applicability of the Proposed Method

The proposed redesign solutions, as described in Section 4.2, Step 5, demonstrate how the integration of satisfiers and barriers into the design process can lead to more meaningful changes and needs-based improvements in PSSs. Unlike conventional customer-requirement-based approaches—such as QFD or the Kano model—that primarily focus on satisfying customer requirements, our method centers on the fulfillment of fundamental human needs, as conceptualized by Max-Neef.

By explicitly mapping functions to satisfiers and barriers, the proposed framework enables designers to identify not only what should be added to fulfill unmet needs, but also what should be removed or modified to mitigate negative impacts. This dual perspective allows for redesign proposals that are not only functionally effective but also socially responsible. In this sense, the method contributes to the discussion on social sustainability, specifically by addressing the aspect of fundamental human-need fulfillment. Rather than focusing solely on the satisfaction of customer requirements, the proposed framework enables designers to reason about how specific functions might relate to satisfiers and barriers. This structured linkage allows for a more deliberate consideration of the manner in which design decisions may contribute to or hinder fundamental human needs such as protection, freedom, understanding, and affection.

This study primarily contributes to the literature of the field by proposing a novel needs-based design method, in addition to describing a smart-cart case study as a demonstration of its applicability. Through this case study, we confirmed that redesign functions can be systematically derived from the analysis of satisfiers and barriers. This demonstrates the method’s potential to support a sufficiency-oriented and socially responsible design processes.

While it would be ideal to evaluate the effectiveness of the resulting redesign solutions, we consider such empirical assessment to be outside the scope of this study and a valuable direction for future research. For instance, satisfiers and barriers could be incorporated into a framework like QFD to assess how well each function supports fundamental human needs. Additionally, qualitative assessments involving experts or users could offer insights into improvements in sufficiency.

Importantly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first design method that explicitly supports function-level redesign based on fundamental human needs. While the smart cart was used as a case example, the proposed method is not limited to this context and can be applied to other PSSs, including sharing services. We believe this generalizability strengthens the method’s contribution to socially sustainable design practices.

5.2. Model of Connections Between the Functions of a Product–Service System and Satisfiers/Barriers

In this study, we combined service blueprints and value graph analysis to extract the functions and requirements of the target PSS. We then used paired comparisons to connect these requirements to satisfiers/barriers, as defined by Max-Neef’s framework.

As a result, nine out of fifty-two satisfiers (17%) and five out of seventy-four barriers (7%) for physical stores, and eighteen out of seventy-one satisfiers (25%) for online stores were successfully linked to functions. Notably, the proportion of barriers connected was less than half that of that associated with satisfiers. This imbalance can be attributed in part to the typical tendency in design processes to express requirements and functions in positive terms. For example, when describing a stove, a designer may specify the function “heat water”, which fulfills a requirement such as “producing hot water.” However, negative aspects such as “overheating and causing burns” are rarely represented explicitly in requirement formulations.

In the case of smart carts, the requirement “information selection by customers” was connected to the satisfier “options”, reflecting the customer’s ability to make autonomous choices. However, the same requirement could also be interpreted as being connected to the barrier “vague product information”, since customers may miss relevant information if it is not easily visible or structured. This example illustrates the difficulty in directly linking requirements to satisfiers or barriers due to the differences in levels of abstraction.

Unlike the connection between requirements and functions—which can often be derived by repeatedly asking “why” a function is needed—the connections between requirements and satisfiers/barriers are more interpretive and context-dependent. These connections tend to rely heavily on the manners in which satisfiers and barriers are defined or understood by designers. As such, further refinement of the conceptual structure, such as rephrasing requirements at a higher level of abstraction, may help facilitate more consistent and meaningful mappings in future applications.

5.3. Method Used to Redesign Functions

In this study, we proposed three methods for functional redesign. New functions were proposed using one or more of these methods, indicating that they were effective for functional redesign. In particular, methods (1) and (2) are considered to be helpful for clarifying the direction of ideas because of the relationships not only between requirements and functions, but also between requirements and satisfiers/barriers.

A fourth method, (4) the removal of functions that do not connect to both satisfiers and barriers, was not included in this study because it targeted the improvement of sufficiency; this method may be considered when aiming to be effective in reducing environmental impact. Modern products have become too multifunctional and therefore contain many functions that do not contribute to sufficiency. Reductions in unnecessary functions lead to reductions in product complexity and the number of parts, which in turn leads to reductions in environmental loads during manufacturing and disposal, due to improved ease of disassembly [59,60]. This fourth method may be effective for identifying such functions.

In this study, the number of functions and requirements was relatively small, so the results could be presented in a diagram, as shown in Figure 7, but as the numbers of functions and requirements increase, it becomes more difficult to represent them. In such cases, it will be effective to model and analyze the results in a matrix format instead of a diagram format [61]. Also, while the analysis of whether these functions realize satisfiers/barriers was performed based on the binary presence or absence of a connection, it may be effective to analyze the strength of the connection.

5.4. Needs-Based Workshop for a Supermarket

Generally, needs-based workshops gather residents in a target location, such as a region or environment, and extract satisfiers and barriers for that area. In this study, because the design target was smart carts used in supermarkets, supermarkets were selected as the target place and satisfiers/barriers were extracted from the customers.

Table A4 shows some results from a needs-based workshop held in Osaka, Japan in 2020 by the authors [57]. Comparing Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3 with Table A4 shows that more specific expressions of satisfiers and barriers were extracted in the workshop targeting supermarkets. At the same time, many satisfiers and barriers associated with requirements were also extracted. For example, “fewer employees”, which is a barrier to freedom in physical stores, is related to the requirement for stores to have more sales assistants, and it is unlikely that “fewer employees” inhibits freedom. Perhaps freedom is inhibited because there are fewer sales assistants, so people cannot understand how to use tools such as tablets and scanners, and their options are narrowed. Conversely, some barriers, such as “little communication”, which is a barrier to affection in physical stores, can be understood as clearly inhibiting fundamental human needs. This variation suggests that the level of abstraction in satisfiers and barriers is influenced by the focus and facilitation of the needs-based workshop.

Therefore, in applying the proposed method, it is important to consider how the design and scope of the workshop affect the granularity and usefulness of the extracted satisfiers and barriers. In this study, the number of participants per group was comparable to previous needs-based workshops, and thus the group size is unlikely to have significantly affected the results. However, differences in participants’ ages and genders may have influenced the satisfiers and barriers extracted. In particular, the participants were not grouped by age, and gender balance was not strictly maintained in each group. These factors may have contributed to variations in the abstraction level and content of the extracted elements. Future research should therefore examine not only how to optimize workshop facilitation methods to balance contextual relevance with the appropriate level of abstraction, but also how participant demographics and group composition may influence the outcomes of needs-based workshops in sufficiency-oriented design.

6. Conclusions

In this study, which aimed to improve the sufficiency of products and services for the realization of SCP, we proposed a needs-based redesign method that redesigns product and service functions to improve their sufficiency by combining the HSD framework proposed by Max-Neef, service blueprints used in the design of PSSs, and value graphs used in engineering design. The contribution of the proposed method is its ability to model connections from the product and service functions to the satisfiers and barriers, and use this model to redesign functions.

We applied the proposed method to a supermarket smart cart, and the results confirmed that the proposed method can propose functions to improve the sufficiency for customers. However, some limitations of the proposed method were also identified: first, there is the question of how to connect functions and barriers, and another limitation is in the question of how to define satisfiers and barriers during system design. These may require new concepts that have not yet been addressed in engineering design.

Product and service design using satisfiers and barriers is one possibility for sufficiency design, and in the future, it will be necessary to increase the number of cases, while at the same time developing methods to improve the structures that were not targeted in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.; methodology, H.M.; validation, H.M. and H.K.; formal analysis, H.M.; investigation, H.M.; resources, H.M.; data curation, H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.; writing—review and editing, H.M.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank T. Hirose, Toshiba Tec Corporation, for useful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCP | Sustainable consumption and production |

| HSD | Human-scale development |

| PSS | Product–service system |

| QFD | Quality function deployment |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Satisfiers in physical stores. (N/A = Not Available).

Table A1.

Satisfiers in physical stores. (N/A = Not Available).

| Being | Having | Doing | Interacting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence | healthy | N/A | buying foods, going to a shop | easy accessibility, helping each other, store for everyone |

| Protection | secure | N/A | using an eco-bag, convey my thoughts | rule compliance, information on products bought is not stored, always something you want, electricity in the store even in the case of a disaster |

| Affection | with someone, accepted | N/A | feeling grateful, feeling the personality, perceiving the producer’s care and dedication | store that makes us feel the seasons, gathering place (without buying), store rooted in the community, special feeling |

| Understanding | N/A | similar experiences | observing, associating with the product, broadening my horizons, going to the shop | dissemination of various information, dissemination of adequate information, interest in new things, love of new things |

| Participation | N/A | rewards card | recycling trash | reflecting opinions, ingenuity to facilitate participation, various ways to participate |

| Idleness | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Creation | N/A | interest in new things, love of new things | becoming a producer, talking to people who don’t use supermarkets, acting and thinking | someone I can talk to, dissemination of various information |

| Identity | N/A | belief, principles, preferences, self-understanding | going to a shop I’ve never been to | supermarkets only in the local area |

| Freedom | capable of anything | information, options, means | challenging, having many options | N/A |

Table A2.

Barriers in physical stores.

Table A2.

Barriers in physical stores.

| Being | Having | Doing | Interacting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence | in poor health, lack of products that seem safe | additive, items with high environmental impact, over-packaging, allergy, toxicant, virus (COVID-19) | buying overpriced items, choosing only high-calorie foods, telling a lie | no barrier-free paths, poor security around the store, traffic conditions, no stores nearby, disaster, only accessible by car, no allergy-friendly products |

| Protection | lost without knowing where to buy, easy for elderly cars to crash into, restricted who can enter, crowded | shopping bag, unsanitary foods | bringing children, losing track of the child | climate change, many imported items, spacious store, far from police station, excessive labor, many bad people, no windows kids running around, large parking space, mass production and consumption |

| Affection | tired, dirty, unsanitary, too low price, high price | no kindness, processed goods, items placed in a messy manner, little communication, sales of side dishes, food loss in stores | complaining in a harsh tone, taking from products with longer expiration dates, bad responding from the clerk, not carrying the products the family wants, not knowing the manufacturer | decline of local stores, no producer label, dirty shopping basket, cold waitresses, clerks with a bad attitude |

| Understanding | unsure how to use, counterfeited place of origin | unknown instructions or recipes, difficult items, misleading information, vague product information, excessive information, no price indication, deceptive advertising | shopping in less time, forgetting my glasses, going to a noisy place, not providing accurate information, greenwashing | advertisements that create preconceived notions, confusing price display, clerks lacking knowledge, shortened operating hours, masks and partitions |

| Participation | required to be a member, not a member, no discounts available due to non-membership | many items, many tasks, a small child, no notice of sale | forgetting to wear a mask, eating out, forgetting my rewards card, registering as a member | shortened operating hours, distant distance to stores, rainy day handling, crowded parking, lack of knowledge by employees, sold all kinds of things, inappropriate responding, no barrier-free access |

| Idleness | difficult to just look at items, spoken to | shopping apps, discount flyers, rewards card | going shopping for daily necessities, seeing a discount on a product I want, sacking | nobody but me can go shopping, music and advertising in the store, dirty toilets, lack of rest area, excessive handling, excessive advertising |

| Creation | coerciveness, tired, sold as a product kit | seasoning for single use, special detergent, no time to think, stereotype, goods at home, shopping list, cheap items, obvious answer, everything I want, unprocessed fish, fewer options | buying pre-cooked products, buying a cooking kit, not making one myself, choosing items in easy-to-reach positions | confusing display of items, advertisements in magazines and on TV, lack of variation, fewer items on display, fixed items, bundle selling |

| Identity | not a price I’m willing to pay, no size that I want, satisfied with what I have | recommendation of a friend, confidence in the brand, sense of discrimination, prejudice, limited personal choice | selecting based on low price, buying recommended products, buying brand name goods, buying as recommended, using the same ones as everyone else, using discount coupons, choosing products with someone else | different products for sale in different regions, TV advertising, products setting by the store, no place for requests to be heard, lack of variation, intrusive behavior |

| Freedom | in closing time, not a member, not available to hold in hands, interrupted | products difficult to dispose of, bundle, rewards card, sense of discrimination, high price | shopping in a fraction of the time, selecting by price, considering family preferences, going shopping with children, not matching the business hours with the rhythm of my life | working environment, excessive customer service, price, uncomfortable accounting due to lack of employees, small variety of items, short business hours, no refills, fewer employees |

Table A3.

Satisfiers in online stores. (N/A = Not Available).

Table A3.

Satisfiers in online stores. (N/A = Not Available).

| Being | Having | Doing | Interacting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence | healthy | means of communication, money, willingness to buy, food availability | choosing safe ingredients, buying what’s good for health, shopping, staying healthy | online supermarket, proper temperature control and transportation, food quality control and preservation |

| Protection | protected personal information, honest | security, relief, safety, no need to go out | setting a password, searching for reviews, making sure the company is safe | secure membership site, inquiry support, check for broken eggs, prevention of intrusion of suspicious persons, safe driving, separated by refrigerated, frozen, and room temperature |

| Affection | N/A | family, producer information, love for family, desire to cook for you | thinking of my family, knowing the story of products, asking what you want to eat, serving your favorite homemade food, receiving words of kindness, knowing food preferences in the family | wide variety of products, shopping list, project that tries to make users’ lives more enjoyable, never out of stock |

| Understanding | intuitive, easy to search for products | production and processing information, information on how to use the ingredients, payment method such as credit card, information on how to use an online supermarket, ingredient allergies | learning about the product development story, finding out what you need to know, knowing the attitude of the supermarkets and their approach to society, knowing the rationale for price, understanding how online supermarkets work, comparing and contrasting, enlarging product image | inquiry support, information about producers and products, careful product description, clear product image |

| Participation | available when I want | reason not to use real stores, expectation, online supermarket I want to use, PC/smartphone, internet literacy, interests, concerns, awareness, benefits of participation, first time use discount | gathering information from reviews, registering as a member, learning about the unique benefits of online supermarkets, earning points, matching delivery time with the time I want to pick up | reviews that show advantages, ease of member registration, delivery area, demonstration |

| Idleness | easy to buy | package receiving options, plan, time, subscription, nothing to think about, automatic selection of what to buy | setting up a pickup box, deciding on a menu, deciding what to buy, taking advantage of gaps in time, buying anytime, anywhere, not buying anything extra | regular delivery, recommendation, subscription delivery, past history purchase, automatic selection |

| Creation | N/A | social media, good memories of the past, request from family, number of recipes, knowledge and wisdom about shopping and cooking, recipes for popular dishes, good combination, ability to search | deciding on a menu, thinking about what is missing, asking what others are making, finding out how to use the ingredients, knowing the season, having a recipe in mind | recommendation, recipe suggestions tailored to the ingredients |

| Identity | in fashion, told that it tastes good, praised by family members, recognized for the hard work, praised for buying good stuff | information on trends, shopping deals, information on seasonal ingredients, family smiles, information on sales campaign, recipes for popular dishes, good arrangements | buying my favorite foods, making the best use of my spare time, finding out on social media, arranging to my liking, buying quickly, getting a good deal, completing of work as a homemaker | team spirit, suggestions for dishes I don’t know |

| Freedom | available for order 24 h, free to cook | easy operation and routine, money, options of pick-up time, no need to go to the supermarket, no need to move, no need to wander around | buying in the gap time, shopping light and easy, shopping without worrying about time, deciding on my own, shopping without worrying about weight, shopping while rummaging around, buying whatever I like, taking my time in choosing, making what you want to make | language-independent, free shipping, anytime, anywhere |

Table A4.

Satisfiers in Osaka, Japan.

Table A4.

Satisfiers in Osaka, Japan.

| Being | Having | Doing | Interacting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsistence | healthy, satisfied with necessities of life, free from illness and injury, able to sleep, able to eat, breathing | willpower, necessities of life, goal, balanced schedule of work and play, collaborator | breathing, drinking water, eating, thinking, working, creating, eating delicious food, being recognized, helping others, making food | space to interact with others, enough food, clothing, and shelter, not too cold |

| Protection | safe, satisfied with oneself, relieved, comfortable with one’s mind, financially secure | status, money, child, family, affection, social security system, law, authority, helpful neighbors | asking for help, loving, expressing through words, asking for advice, feeling affection, satisfying the needs of others, having pets | filled with resources, safety space, full of kind people, law, friendly relations with other countries, internet security |

| Affection | kind to others, together with girlfriend, mentally healthy, safe, loved, loved by others, comfortable, not alone | lover, experience of being loved, self-esteem, affection, sense of education, something very cute, free time | having a special connection, hugging, spending time together, confessing my love, kissing, spending time with my family, acknowledging | good family environment, full of love |

| Understanding | curious, familiar with cultural background, able to talk | relationship, interest, motivation, free time, knowledge of many different fields, sympathy, intelligence, acceptance, experience in life, willingness to understand, literacy, ability to use a computer | discussing, searching, recognizing, experiencing the same thing, getting necessary information, reading books, observing, asking, speaking the same language, listening to others | school, freedom of speech, active discussion, sharing social context, place with teacher, sharing information, place to talk with others, wealth of resources |

| Participation | curious, fine, lonely, capable of growth through participation | sense of purpose, money, free time, interest, transportation, PC, courage, friend, IT literacy, benefit | recognizing things as important, having an interest, meeting with someone, making friends, acquiring knowledge, belonging to a group, search for interesting events, finding out about events, getting a chance, networking, taking over knowledge and experience, seeking | free event, suitable participation requirements, attracting public attention, means of communications, transportation system reward, everyone participating, comfortable place, reflecting on my opinions, communicating easily, participatory event, places to go to |

| Idleness | tired, sleepy, cheerless, overwhelmed, accessible to necessities | free time, assistant, calm mind, money, house, peaceful mind, no work | making time, completing all tasks, tidying up | nothing to do, my mother taking care of me, communication failure, closed store, silence, warm room, safe place, nature, full of food and water |

| Creation | curious, creative, satisfied, dreamy | person of action, money, idea, knowledge, experience, ideas from others, free time, material, patience, purpose | crafting, looking for ideas, brainstorming, making time, sharing, discussing, thinking about what I can do, walking, taking a bath, playing with a smartphone, participating in events | worked on by many people, sufficient resources, desired by many people, free discussion, having all the essential knowledge, surrounded by materials, relaxed mood, place with teacher, existence of people willing to pay for it, existence of friends who can create together, convenience required |

| Identity | responsible for oneself, self-expressive | stranger, belonging, social status, strong belief, talent, name, friend, social media account, identified affiliation | working diligently on something, belonging, recording, posting on social media, doing a presentation, making others recognize me, talking, stating my opinions | free to do, all backgrounds respected, lack of identity-based conflict, respecting individuality, accepting me, offering information, existence of people who praise me, well-educated, place with others, no denial when I communicate my intentions |

| Freedom | responsible for oneself, limited by law, restricted in activity, time-limited, unrestricted, sleepless, decisive, satisfied with a certain amount of freedom, able to go where I want to go | authority, ability, free time, knowledge, ideal, money, technological capability, brainwashing, adaptability to society, mental strength, necessities, target to aim at | recognizing my limitations, living an independent life, setting limits for myself, joining the demonstration, leaving home, living a self-sufficient life, prioritizing, stopping comparing myself to others | less restrictive regulations, certain restrictions, support for ambition, feeling free, no oppression, no information control, information unobtainable |

References

- UN Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- UNEP. Global Outlook on Sustainable Consumption and Production Policies; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Umeda, Y.; Takata, S.; Kimura, F.; Tomiyama, T.; Sutherland, J.; Kara, S.; Herrmann, C.; Duflou, J. Toward integrated product and process life cycle planning—An environmental perspective. CIRP Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2012, 61, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, M.; Yannou, B.; Leroy, Y.; Cluzel, F.; Kendall, A. A taxonomy of circular economy indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; Bey, N.; Niero, M.; Hauschild, M. Circular economy considerations in choices of LCA methodology: How to handle EV battery repurposing? Procedia CIRP 2020, 90, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswiet, J.; Hauschild, M. EcoDesign and future environmental impacts. Mater. Des. 2005, 26, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Germani, M.; Zamagni, A. Review of ecodesign methods and tools. Barriers and strategies for an effective implementation in industrial companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunn, V.S.C.; Bocken, N.M.P.; van den Hende, E.A.; Schoormans, J.P.L. Business models for sustainable consumption in the circular economy: An expert study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasawa, E.; Shibata, T.; Sugiyama, H.; Hirao, M. Environmental potential of reusing, renting, and sharing consumer products: Systematic analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suski, P.; Speck, M.; Liedtke, C. Promoting sustainable consumption with LCA–A social practice based perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 125234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, D.; Yang, Z.; Ma, S. Unraveling customer sustainable consumption behaviors in sharing economy: A socio-economic approach based on social exchange theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M. Sustainable consumption and wellbeing: Does on-line shopping matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 1112–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, H.S.; Mosgaard, M.A. A review of micro level indicators for a circular economy–moving away from the three dimensions of sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.; Beitz, W. Engineering Design: A systematic Approach, 3rd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, K.T.; Eppinger, S.D. Product Design and Development; McGraw-Hill: Burlington, VT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weilkiens, T. Systems Engineering with SysML/UML; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- INCOSE. INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sakao, T.; Shimomura, Y.; Lindahl, M.; Sundin, E. Applications of service engineering methods and tool to industries. In Innovation in Life Cycle Engineering and Sustainable Development; Brissaud, D., Tichkiewitch, S., Zwolinski, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzotta, G.; Pirola, F.; Pinto, R.; Akasaka, F.; Shimomura, Y. A Service Engineering framework to design and assess an integrated product-service. Mechatronics 2015, 31, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shostack, G.L. How to design a service. Eur. J. Mark. 1982, 16, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasantha, G.V.A.; Roy, R.; Lelah, A.; Brissaud, D. A review of product-service systems design methodologies. J. Eng. Des. 2012, 23, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Gupta, J.; Qin, D.; Lade, S.J.; Abrams, J.F.; Andersen, L.S.; McKay, D.I.A.; Bai, X.; Bala, G.; Bunn, S.E.; et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 2023, 619, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. A doughnut for the Anthropocene: Humanity’s compass in the 21st century. Lancet Planet Health 2017, 1, e48–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M. Human Scale Developmenmt; The Apex Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Royo, M.; Temesgen, A.K.; Vangelsten, B.V. Towards sustainable transport practices in a coastal community in Norway: Insights from human needs and social practice approaches. In Consumption, Sustainability and Everyday Life; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 255–289. [Google Scholar]

- Jolibert, C.; Max-Neef, M.; Rauschmayer, F.; Paavola, J. Should we care about the needs of non-humans? Needs assessment: A tool for environmental conflict resolution and sustainable organization of living beings. Environ. Policy Gov. 2011, 21, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyal, L.; Gough, I. A theory of human needs. Crit. Soc. Policy 1984, 4, 6–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clube, R.K.; Tennant, M. The Circular Economy and human needs satisfaction: Promising the radical, delivering the familiar. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 177, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clube, R.K.; Tennant, M. What Would a Human-Centred ‘Social’ Circular Economy Look Like? Drawing from Max-Neef’s Human-Scale Development Proposal. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Fukushige, S. A living-sphere approach for locally oriented sustainable design. J. Remanuf. 2018, 8, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M. Realising the ‘wellbeing dividend’: An exploratory study using the Human Scale Development approach. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.; Stahel, A.; Max-Neef, M. Towards a systemic development approach: Building on the Human-Scale Development paradigm. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M.; Guardiola, J.; Garcia-Quero, F. Sustainable development in times of economic crisis: A needs-based illustration from Granada (Spain). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. From here to Utopia: Running a human-scale development workshop on the Gold Coast, Australia. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Sumimura, Y.; Dinh, C.N.; Tran, M.; Murata, H.; Fukushige, S. Needs-Based Workshops for Sustainable Consumption and Production in Vietnam. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Ball, P., Huatuco, L.H., Howlett, R.J., Setchi, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 155, pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gimelli, F.; Rogers, B.C.; Bos, J.J. Linking water services and human well-being through the fundamental human needs framework: The case of India. Water Altern. 2019, 12, 715–733. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, H.; Kobayashi, H. Proposal of a Connecting Method between Product Structures and Fundamental Human Needs. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Environmentally Conscious Design and Inverse Manufacturing, Yokohama, Japan, 25–27 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, H.; Fukushige, S.; Murata, H. A Framework for Locally-oriented Product Design Using Extended Function-structure Analysis and Mixed Prototyping. Glob. Environ. Res. 2021, 25, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kmenta, S.; Ishii, K. Advanced FMEA using meta behavior modeling for concurrent design of products and controls. In Proceedings of the 1998 ASME DETC, Atlanta, GA, USA, 13–16 September 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, K. Textbook of ME217 Design for Manufacture: Product Definition; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, J.; Clausing, D. The house of quality. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1988, 66, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fähnrich, K.P.; Meiren, T. Service engineering: State of the art and future trends. In Advances in Services Innovations; Spath, D., Fähnrich, K.P., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mont, O. Clarifying the concept of product-service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullinger, H.J.; Fähnrich, K.P.; Meiren, T. Service engineering–methodological development of new service products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 85, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Sakao, T.; Fukushima, R. Customization of product, service, and product/service system: What and how to design. Mech. Eng. Rev. 2019, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Morgan, F.N. Service Blueprinting: A Practical Technique for Service Innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 50, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geum, Y.; Park, Y. Designing the sustainable product-service integration: A product-service blueprint approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Perez, J.; Teixeira, J.G.; Romero-Piqueras, C.; Patricio, L. Designing sustainable services with the ECO-Service design method: Bridging user experience with environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed.; Longman: London, UK, 1987; pp. 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social well-being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, J.; Bogner, K.; Becker, M.; Schlaile, M.P.; Pyka, A.; Ebersberger, B. Crisis-driven innovation and fundamental human needs: A typological framework of rapid-response COVID-19 innovations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 169, 120799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, H.; Horio, S.; Kobayashi, H. Development of Online Needs-Based Workshop Support System in a Pandemic. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 687754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M. Sustainability and Wellbeing: Human-Scale Development in Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alting, L. Life cycle engineering and design. CIRP Ann. 1995, 44, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, M.Z.; Herrmann, C.; Kara, S. An Integrated Framework for Life Cycle Engineering. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinger, S.D.; Browning, T.R. Design Structure Matrix Methods and Applications; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).