Understanding the Contribution of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in Mangrove Forest Conservation: A Case Study on Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh

Abstract

1. Introduction

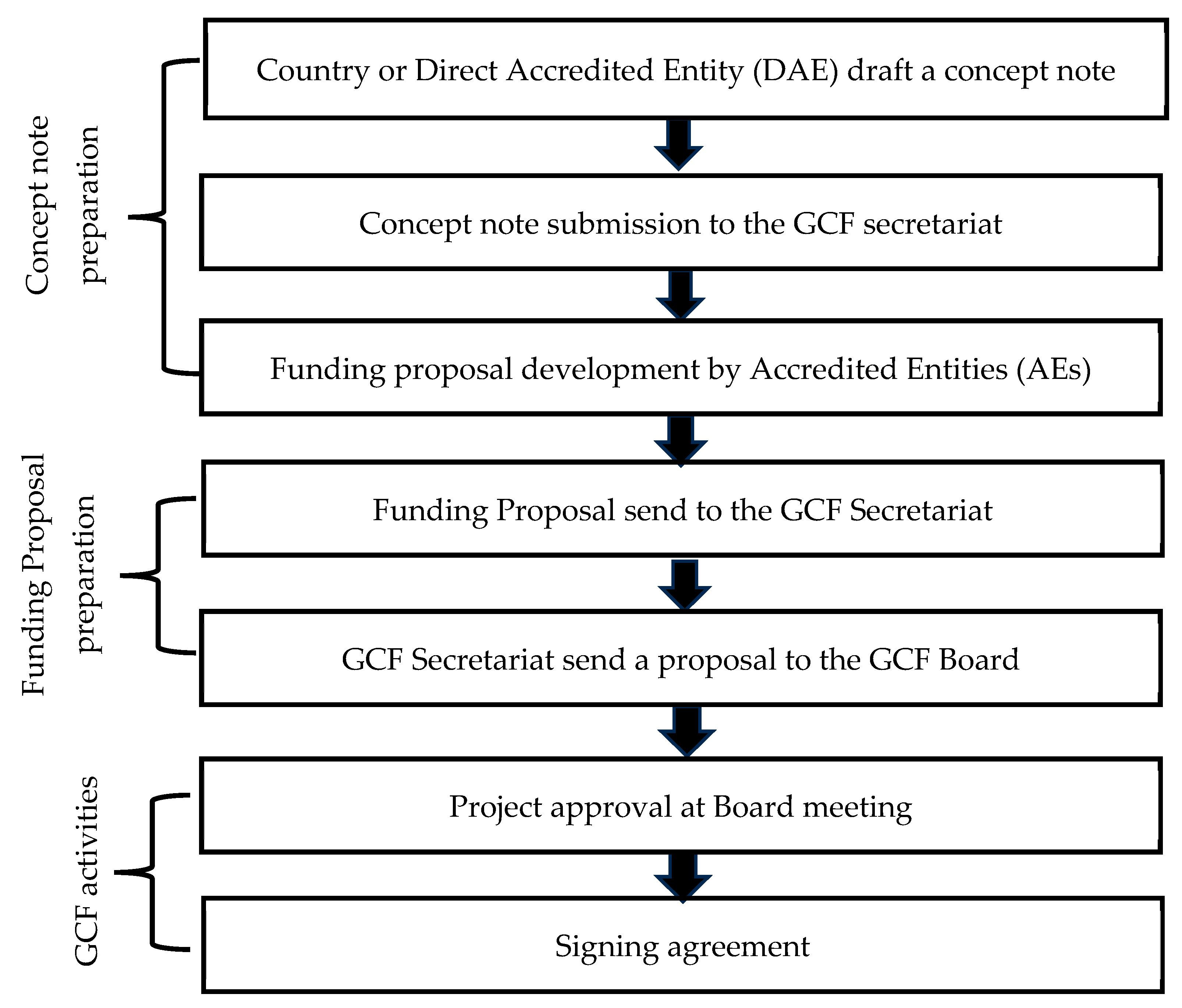

2. Framework of the Green Climate Fund

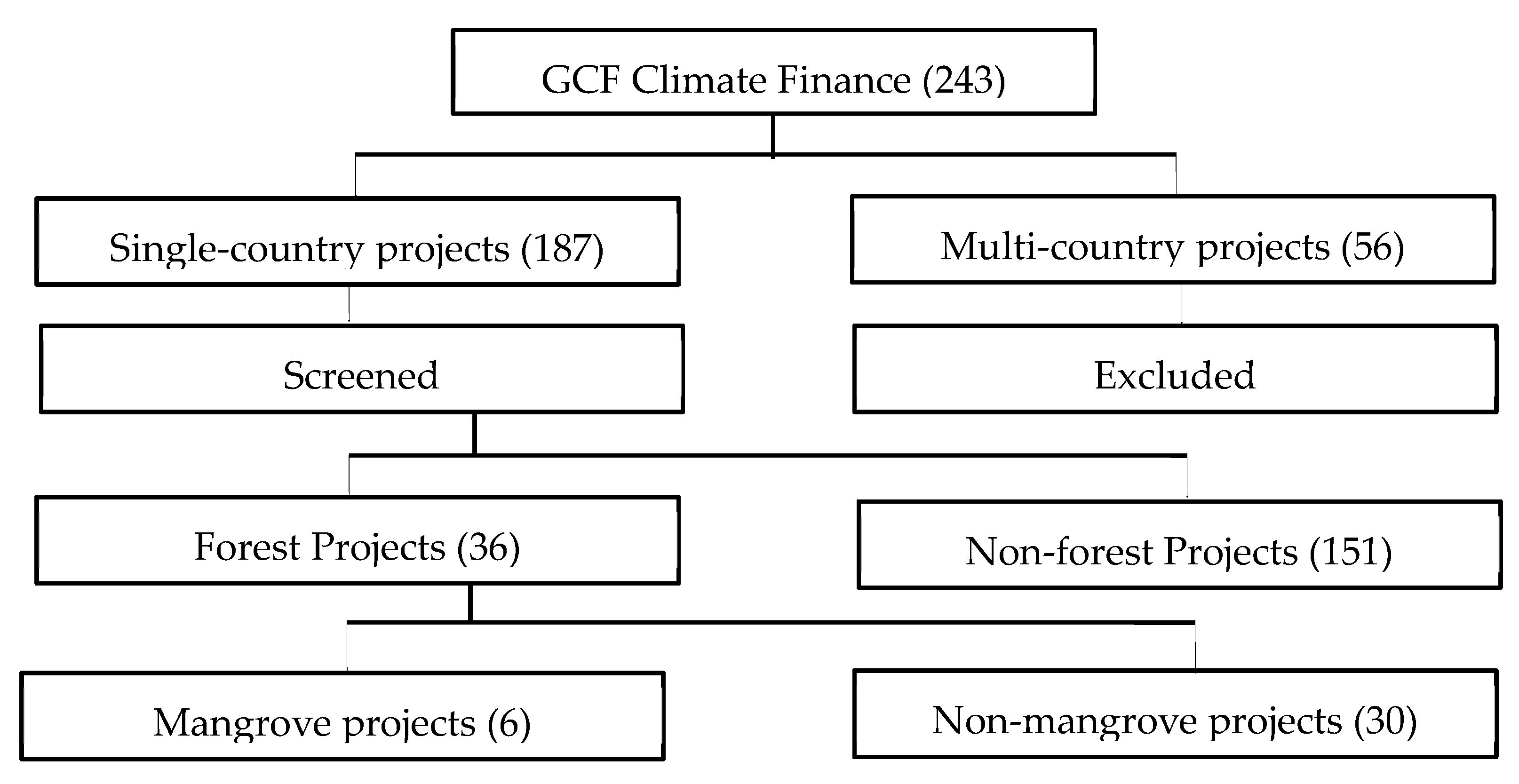

3. Methodology

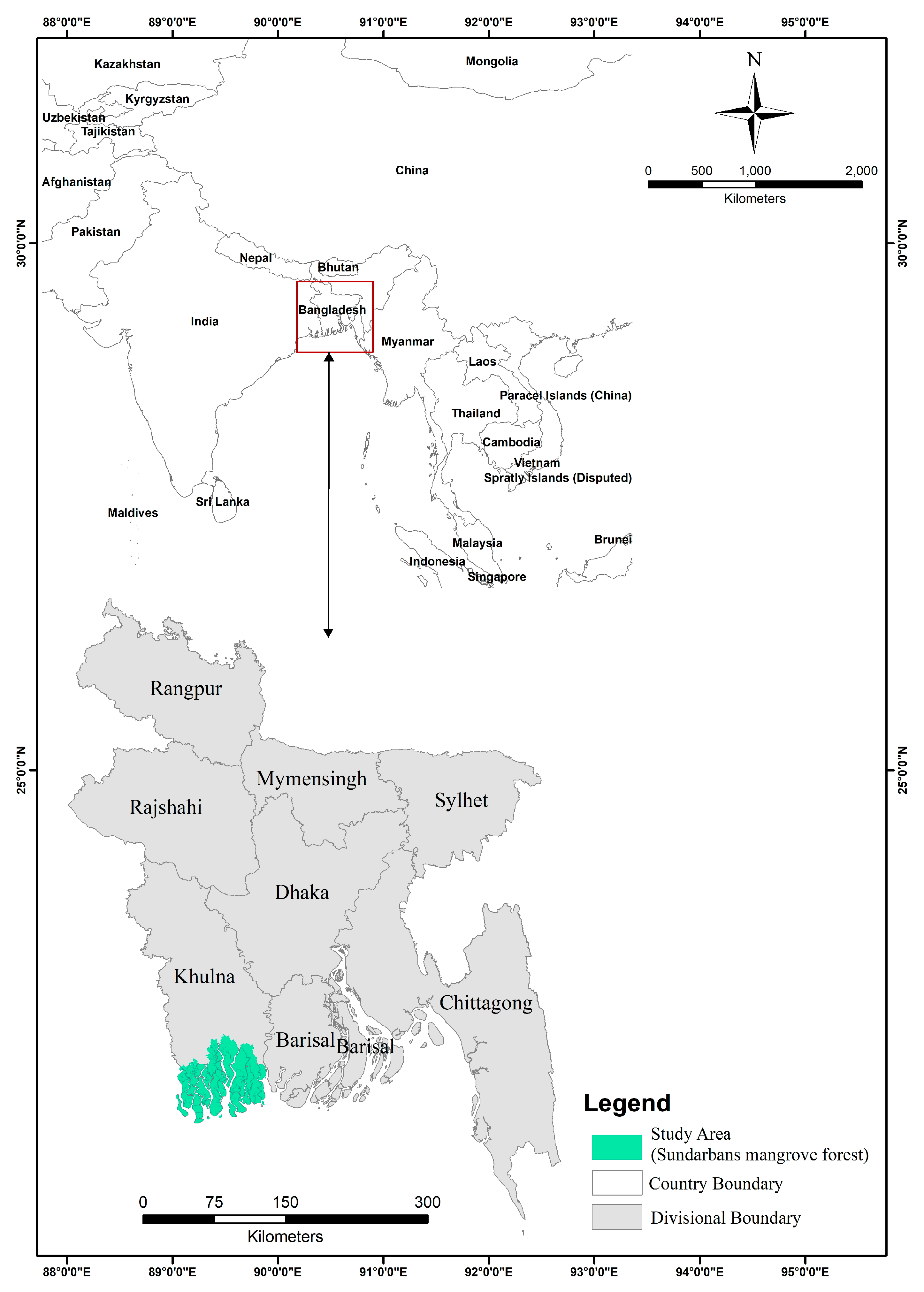

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Materials and Data Source

4. Results and Discussion

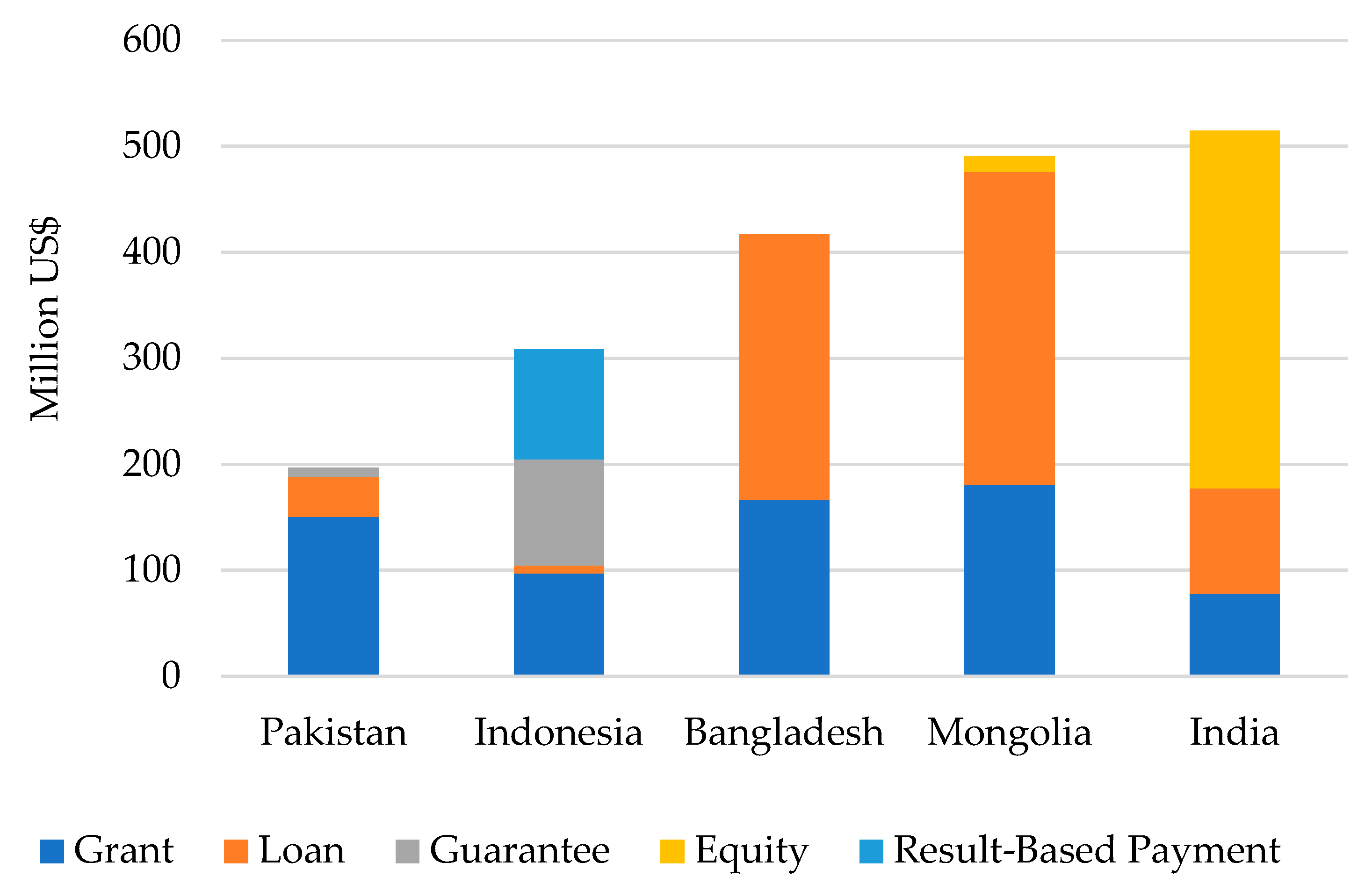

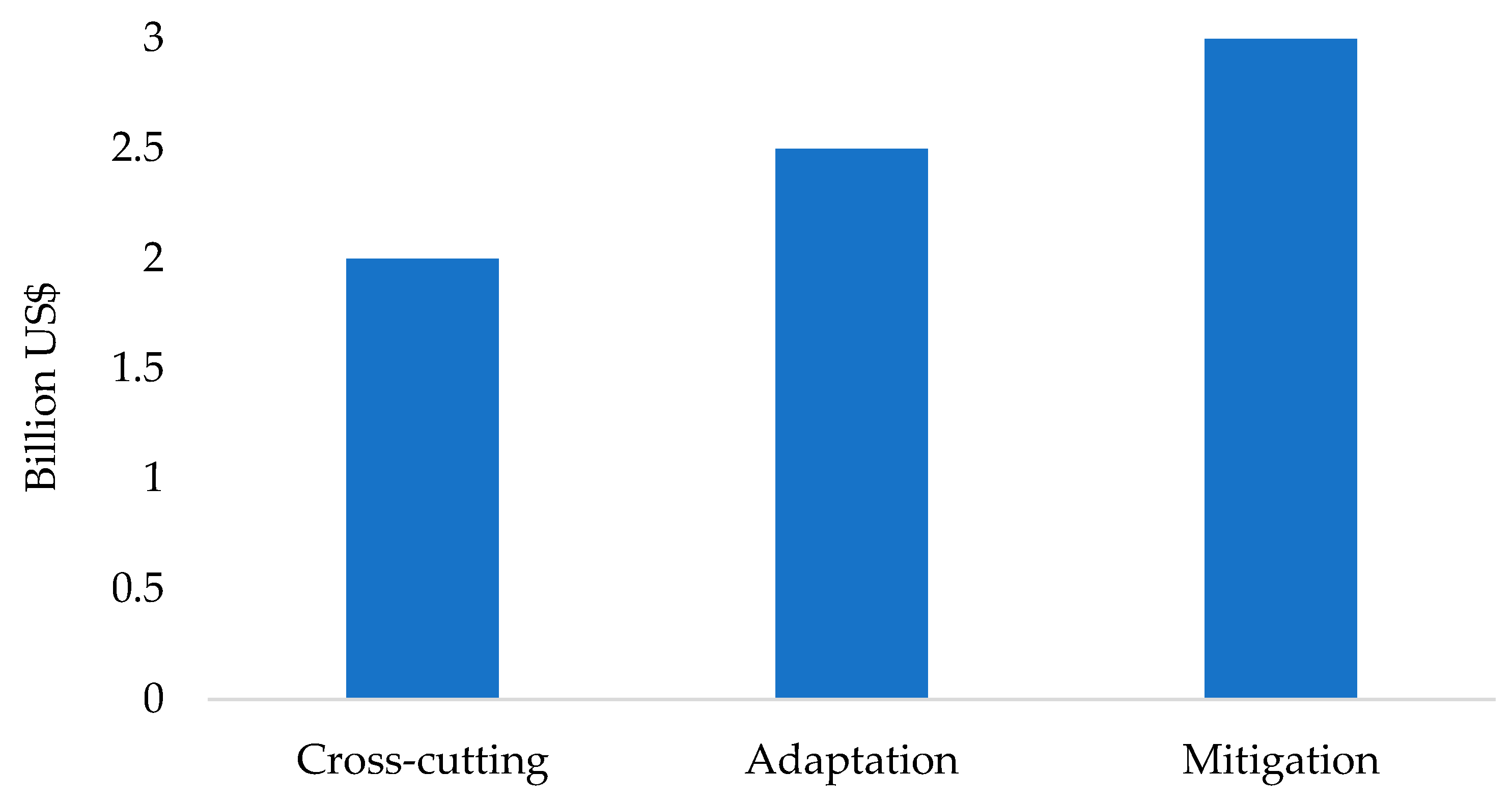

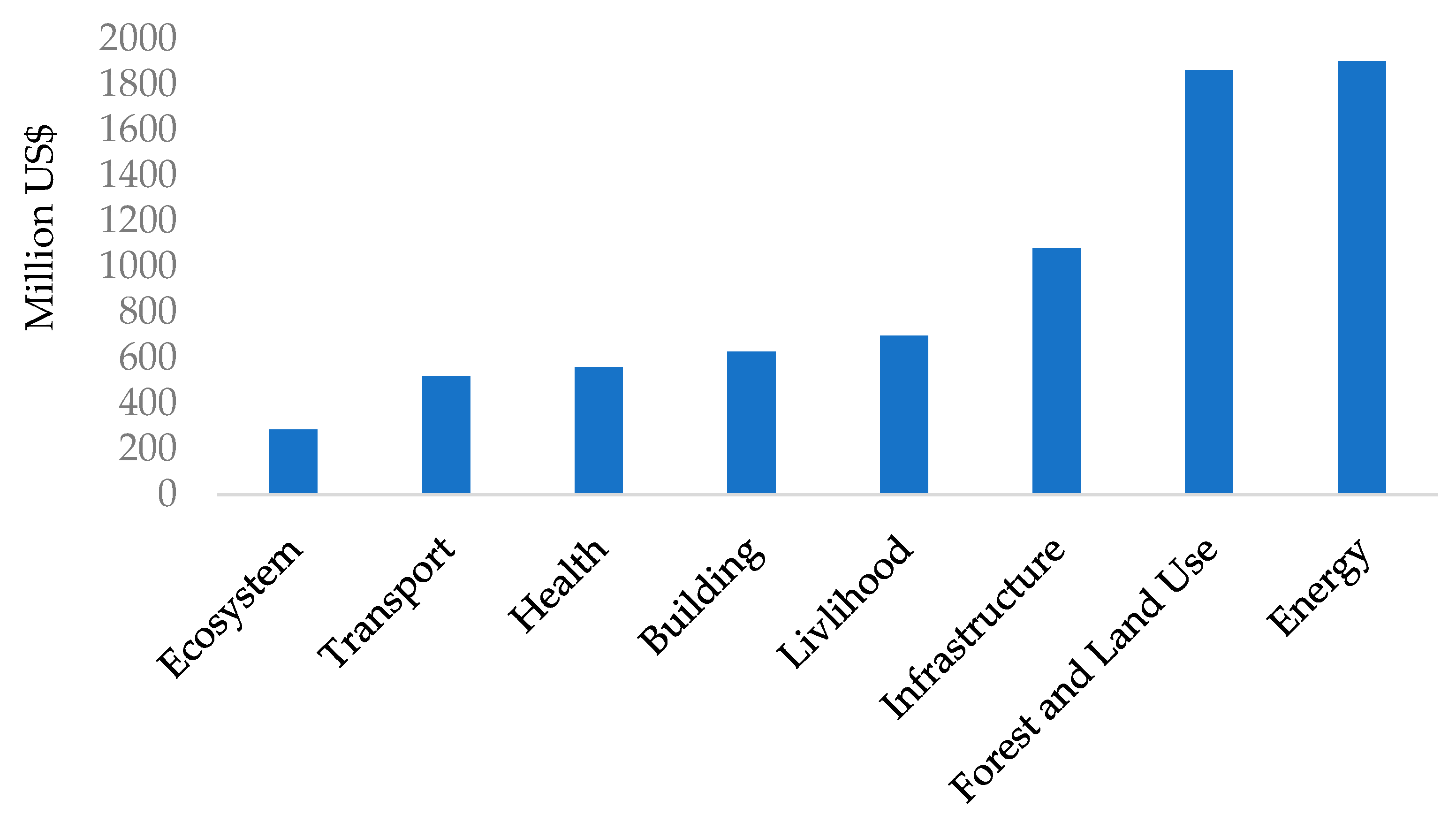

4.1. GCF Allocation Profile and Funding Trend

4.2. Cost Effectiveness of GCF Forest Projects

4.3. GCF Project Trend and Characteristics in Bangladesh

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fonta, W.M.; Ayuk, E.T.; van Huysen, T. Africa and the Green Climate Fund: Current challenges and future opportunities. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.R.; Khan, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Jahan, S.; Islam, K.M.A.; Zayed, N.M. Corruption Possibilities in the Climate Financing Sector and Role of the Civil Societies in Bangladesh. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2021, 56, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amighini, A.; Giudici, P.; Ruet, J. Green finance: An empirical analysis of the Green Climate Fund portfolio structure. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 350, 131383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omukuti, J.; Barrett, S.; White, P.C.L.; Marchant, R.; Averchenkova, A. The green climate fund and its shortcomings in local delivery of adaptation finance. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, J.; Prowse, M.; De Roy, E.; Huang, D. Assessing the likelihood for transformational change at the Green Climate Fund: An analysis using self-reported project data. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 35, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, T. Institutional Innovations and Their Challenges in the Green Climate Fund: Country Ownership, Civil Society Participation and Private Sector Engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kerkhoff, L.; Ahmad, I.H.; Pittock, J.; Steffen, W. Designing the Green Climate Fund: How to Spend $100 Billion Sensibly. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2011, 53, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djabare, K.; Tovivo, K.; Koumassi, K. Five Years of the Green Climate Fund: How Much Has Flowed to Least Developed Countries? Climate Analytics. Berlin, Germany. 2021. Available online: https://climateanalytics.org/publications/five-years-of-the-green-climate-fund-how-much-has-flowed-to-least-developed-countries (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Lewis, S.L.; Wheeler, C.E.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; Koch, A. Restoring natural forests is the best way to remove atmospheric carbon. Nature 2019, 568, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buto, O.; Galbiati, G.M.; Alekseeva, N.; Bernoux, M. Climate Finance in the Agriculture and Land Use Sector–Global and Regional Trends Between 2000 and 2018. Food & Agriculture Org. Rome, Italy; 2021. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/27d14473-c64c-4c23-bfc5-a5bc1c5080d2/content (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Decades of Mangrove Forest Change. What Does It Mean for Nature People and the Climate? UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; ISBN 978-92-807-4019-6. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, C.; Ochieng, E.; Tieszen, L.L.; Zhu, Z.; Singh, A.; Loveland, T.; Masek, J.; Duke, N. Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.S.A.; Uddin, M.B.; Uddin, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.S.H.; Mukul, S.A. Distribution and status of forests in the tropics: Bangladesh perspective. Proc. Pak. Acad. Sci. 2007, 44, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Department. Natural Mangrove Forest (Sundarbans). Available online: https://bforest.gov.bd/site/page/19d63ffe-01e1-4351-b85b-3b60811b87f7/Mangrove-Forest-(Natural---Sundarban) (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Ramsar Sites Information Service. Sundarbans Reserved Forest. Available online: https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/560 (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Dasgupta, S.; Sobhan, I.; Wheeler, D. The impact of climate change and aquatic salinization on mangrove species in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Ambio 2017, 46, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forest Department. Carbon Inventory in Sundarbans. Available online: https://bforest.gov.bd/site/page/6ec068d0-f8ad-4092-8212-39f5bd733c35/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Forest Department. Carbon Inventory in Protected Areas. Available online: https://bforest.gov.bd/site/page/8de0afe8-1bf1-4003-aff2-1c4758f545fa/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Iftekhar, M.S. Protecting the Sundarbans: An appraisal of national and international environmental laws. Asia Pac. J. Environ. Law. 2010, 13, 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Inskip, C.; Ridout, M.; Fahad, Z.; Tully, R.; Barlow, A.; Barlow, C.G.; Islam, M.A.; MacMillan, D. Human–Tiger Conflict in Context: Risks to Lives and Livelihoods in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Karmaker, S.C.; Saha, B.B. Nexus between potentially toxic elements’ accumulation and seasonal/anthropogenic influences on mangrove sediments and ecological risk in Sundarbans, Bangladesh: An approach from GIS, self-organizing map, conditional inference tree and random forest models. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alongi, D.M. The Impact of Climate Change on Mangrove Forests. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2015, 1, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik, S.; Rahman, R. Community engagement in analyzing their livelihood resilience to climate change induced salinity intrusion in Sundarbans mangrove forest. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Coastal Zones and Climate Change: Assessing the Impacts and Developing Adaptation Strategies, Melbourne, Australia, 12–13 April 2010; pp. 445–464. [Google Scholar]

- Getzner, M.; Islam, M.S. Natural resources, livelihoods, and reserve management: A case study from Sundarbans mangrove forests, Bangladesh. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2013, 8, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenhunen, S.; Uddin, M.J.; Roy, D. After cyclone Aila: Politics of climate change in Sundarbans. Contemp. South Asia 2023, 31, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.A.; Haque, M.M.; Hinchliffe, S.J.; Guilder, J. A sequential assessment of WSD risk factors of shrimp farming in Bangladesh: Looking for a sustainable farming system. Aquaculture 2020, 526, 735348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finance Division. Bangladesh Climate Fiscal Framework 2020. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/bd/Updated-Climate-Fiscal-Framework-2020.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) 2021 Bangladesh (Updated). 2021. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/NDC_submission_20210826revised.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Manzanares, F.J. The Green Climate Fund—A beacon for climate change action. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2017, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund. Boardroom. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/boardroom (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Bertilsson, J.; Thörn, H. Discourses on transformational change and paradigm shift in the Green Climate Fund: The divide over financialization and country ownership. Environ. Polit. 2021, 30, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund. GCF Project Activity Cycle. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/project-cycle (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Access Funding. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/access-funding/concept-note-screening (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Green Climate Fund. Funding Proposal Template. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/funding-proposal-template (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Tanner, T.; Bisht, H.; Quevedo, A.; Malik, M.; Biswas, S.; Nadiruzzaman, M. Enabling Access to the Green Climate Fund: Sharing Country Lessons from South Asia. Available online: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/35237/1/Tanner%20et%20al.%2C%202019%20Green%20Climate%20Fund%20South%20Asian%20lessons%20-%20ACT.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Ricci, L.; Mangenot, M. Does Climate Finance Support Institutional Adaptive Capacity in Caribbean Small Island and Developing States? An Analysis of the Green Climate Fund Readiness Grants. Climate 2023, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund. Resource Mobilisation. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/resource-mobilisation (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Cui, L.B.; Zhu, L.; Springmann, M.; Fan, Y. Design and analysis of the green climate fund. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2014, 23, 266–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderheiden, S. Justice and Climate Finance: Differentiating Responsibility in the Green Climate Fund. Int. Spect. 2015, 50, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund. Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-annual-report-2023-040919.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Areas of Work. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/countries (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. The Sundarbans. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/798/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Hossain, M.; Rashid, A.Z.M.M. Non-wood Forest Products of the Sundarbans, Bangladesh: The Context of Management, Conservation and Livelihood. In Non-Wood Forest Products of Asia; Editor Rashid, A.Z.M.M., Khan, N.A., Hossain, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 103–140. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.K.D. Local community attitudes towards mangrove forest conservation: Lessons from Bangladesh. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.R.H.; Hossain, M.; Rashid, A.Z.M.; Khan, N.A.; Shuvo, S.N.; Hassan, M.Z. Evaluating co-management in the Sundarbans mangrove forest of Bangladesh: Success and limitations from local forest users’ perspectives. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Rahman, M.A.U.; Rahaman, K.R.; Ha-Mim, N.M.; Haque, S.F. Nexus Between Vulnerability, Livelihoods and Non-Migration Strategies Among the Fishermen Communities of Sundarbans, Bangladesh. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2023, 14, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Nabi, M.R.; Ansari, M.N.A.; Latif, A.; Mahmud, M.R.; Islam, M.S. Ecosystem services of the world largest mangrove forest Sundarban in Bangladesh. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. 2016, 27, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nishat, A.; Chowdhury, J.K. Influence of Climate Change on Biodiversity and Ecosystems in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. In The Sundarbans: A Disaster-Prone Eco-Region; Editor Sen, H.S., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 439–468. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change. The Sundarbans (Bangladesh) (N798) Progress Report on the Decisions of 44 COM 7B.91 the World Heritage Committee on the Sundarbans World Heritage Sites. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/191567 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Islam, D.S.M.; Bhuiyan, M.A.H. Impact scenarios of shrimp farming in coastal region of Bangladesh: An approach of an ecological model for sustainable management. Aquac. Int. 2016, 24, 1163–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Sadath, M.N.; Giessen, L. Foreign donors driving policy change in recipient countries: Three decades of development aid towards community-based forest policy in Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 68, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Environment Facility. Biodiversity Conservation in the Sundarbans Reserved Forest. Available online: https://www.thegef.org/projects-operations/projects/455 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- World Bank. International Development Association Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Credit in the Amount of SDR124.9 Million to the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for a Sustainable Forest & Livelihoods (SUFAL) Project. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/395741538969430897/pdf/P161996-PAD-post-rvp-147pm-09182018.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Roy, G.; Haque, D.M.Z.; Collaborative Forest Management-SUFAL Project Anticipates Success Stories for Bangladesh Forest Department. Forest Department. Available online: https://bforest.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bforest.portal.gov.bd/page/bb40dcf3_5140_49c8_9b54_9b43993607ac/2022-06-29-05-03-71ebe93daf72ab40446dfa40816a7221.pdf#page=20 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Chaudhury, A. Role of Intermediaries in Shaping Climate Finance in Developing Countries—Lessons from the Green Climate Fund. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund. Areas of Work. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sectors (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Themes & Result Areas. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/themes-result-areas (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Pielke, R.A., Jr. An idealized assessment of the economics of air capture of carbon dioxide in mitigation policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. What You Need to Know about Abatement Costs and Decarbonization. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/04/20/what-you-need-to-know-about-abatement-costs-and-decarbonisation (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. FP166: Light Rail Transit for the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM). Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/project/fp166 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- UN Environment. Broken Record Temperatures Hit New Highs, Yet World Fails to Cut Emissions (Again). Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/43922/EGR2023.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Kalinowski, T. The Green Climate Fund and private sector climate finance in the Global South. Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund. Financial Terms and Conditions of Grants and Concessional Loans. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/financial-terms-conditions-grants-loans.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/paris_agreement_english_.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- UN Environment. Global Environment Outlook 6 UNEP-UN Environment Programme. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-6 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Funding Proposal FP084: Enhancing Climate Resilience of India’s Coastal Communities. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/funding-proposal-fp084-undp-india.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Global Bangladesh. Bangladesh External Debt Management: Some Emerging Concerns. Available online: https://globalbangladesh.org/bangladeshs-external-debt-management-some-emerging-concerns/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Green Climate Fund. Resilient Homestead and Livelihood Support to the Vulnerable Coastal People of Bangladesh (RHL). Annual Performance Report CY2023 (for Projects/Programme Approved Under the IRMF). Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/fp206-annual-performance-report-cy2023.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (Bangladesh) (PKSF). Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/ae/pksf (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Palli Karma-Sahayak Foundation (PKSF). About Us. Available online: https://pksf.org.bd/about-us/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Green Fund Climate. FP069: Enhancing Adaptive Capacities of Coastal Communities, Especially Women, to Cope with Climate Change Induced Salinity. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/project/fp069 (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Green Climate Fund. Climate Resilient Sustainable Coastal Forestry in Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/climate-resilient-sustainable-coastal-forestry-bangladesh (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Zou, S.Y.; Ockenden, S. What Enables Effective International Climate Finance in the Context of Development Co-operation? Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/what-enables-effective-international-climate-finance-in-the-context-of-development-co-operation_5jlwjg92n48x.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Cameron, C.; Maharaj, A.; Kennedy, B.; Tuiwawa, S.; Goldwater, N.; Soapi, K.; Lovelock, C.E. Landcover change in mangroves of Fiji: Implications for climate change mitigation and adaptation in the Pacific. Environ. Chall. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Result Areas | Adaptation Projects: Investment Cost to Benefit Per Person (USD) | Mitigation Projects: Investment Cost to Reduce Per MtCO2eq Emission (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Health, food, and water security | 3.87 | 10.67 |

| The livelihood of people and community | 6.68 | 8.87 |

| Energy generation and access | 18.96 | 1.70 |

| Transport | - | 26.41 |

| Infrastructure and built environment | 18.25 | 26 |

| Ecosystem and ecosystem services | 6.61 | 3.75 |

| Buildings, cities, and appliances | 461.93 | 24.74 |

| Forest and land use | 3.61 | 4.34 |

| Area | Number of Projects | Emission Reduction (Total MtCO2eq) | Benefits to Locals (in Millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mangrove | 6 | 5.6 | 43.2 |

| Other tropical forests | 30 | 433 | 38.4 |

| Total | 36 | 438.6 | 81.6 |

| Project (ID) (Year) | Amount (Million USD) | Grant (Million USD) | Loan (Million USD) | Theme | Financing Sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promoting private sector investment through large scale adoption of energy saving technologies and equipment for textile and ready-made garment (RMG) sectors of Bangladesh (FP 150) (2020–2032) | 256.5 | 6.5 | 250 | Mitigation | Private |

| Extended community climate change project-drought (ECCCP-Drought) (SAP 026) (2023–2027) | 25 | 25 | Adaptation | Public | |

| Resilient homestead and livelihood support to the vulnerable coastal people of Bangladesh (RHL) (FP 206) (2023–2028) | 42 | 42 | Adaptation | Public | |

| Extended community climate change project-flood (ECCCP-Flood) (SAP 008) (2019–2024) | 9.7 | 9.7 | Adaptation | Public | |

| Enhancing adaptive capacities of coastal communities, especially women, to cope with climate change-induced salinity (FP 069) (2018–2026) | 25 | 25 | Adaptation | Public | |

| Climate resilient infrastructure mainstreaming (CRIM) (FP 004) (2018–2024) | 40 | 40 | Adaptation | Public | |

| Global clean cooking program-Bangladesh (FP 070) (2019–2023) | 20 | 20 | Cross-cutting | Public | |

| Total | 418.2 | 168.2 | 250 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majumdar, M.S.M.; Matsui, K. Understanding the Contribution of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in Mangrove Forest Conservation: A Case Study on Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083583

Majumdar MSM, Matsui K. Understanding the Contribution of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in Mangrove Forest Conservation: A Case Study on Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083583

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajumdar, Mohammad Sayed Momen, and Kenichi Matsui. 2025. "Understanding the Contribution of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in Mangrove Forest Conservation: A Case Study on Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083583

APA StyleMajumdar, M. S. M., & Matsui, K. (2025). Understanding the Contribution of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in Mangrove Forest Conservation: A Case Study on Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh. Sustainability, 17(8), 3583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083583