1. Introduction

Social media has become a major platform for sharing tourism experiences [

1,

2]. Travelers use these platforms to post diverse travel content, including information, stories, texts, images, and videos, sharing their thoughts, opinions, and ideas [

3,

4,

5]. This growing reliance highlights social media’s increasing role in tourism, influencing travelers’ behaviors such as travel planning [

5,

6], aspirations to visit destinations [

7,

8,

9], and future visiting intention [

10,

11,

12]. As a result, tourist destinations often encourage and incentivize visitors to share their experiences online, not only for marketing purposes but also to foster sustainable tourism behaviors [

5,

13,

14].

However, tourists are not willing to share their travel experiences on social media, as expected by tourism agencies [

15,

16,

17]. Social media platforms like Douyin, Weibo, and Red have become vital in shaping tourism consumption patterns in China, influencing how tourists search for, evaluate, and share travel experiences [

18,

19,

20]. Despite the pivotal role of user-generated content (UGC) in driving consumer behavior—91% of consumers are more likely to buy a product with user-generated photos or videos in reviews [

21]—tourism practitioners face challenges motivating tourists to share their experiences online [

16,

22].

In China, Douyin and Red have over 500 million active users, with short video formats increasingly influencing consumer preferences [

23]. China also boasts 1.092 billion internet users, making social media one of the most powerful tools in tourism marketing. Thus, investigating the factors influencing sharing behavior within the Chinese context is critical for actionable insights into tourism marketing strategies.

Existing studies are largely concentrated in Western countries, and their findings are based on specific cultural and geographical contexts [

4,

15,

24,

25,

26]. This geographic focus reduces the relevance of results, as sharing behavior may differ across cultures and lifestyles [

27]. Consequently, further research is needed to determine whether the same factors apply in the Chinese context. Despite the growing interest in this area, research investigating the factors that lead tourists to share tourism experiences on social media is still limited. Current research in this area remains at a preliminary stage [

4,

22].

Additionally, many studies in this domain lack a strong theoretical foundation, as they often incorporate prior literature without proposing comprehensive conceptual frameworks [

22]. Previous research has examined individual motivations and social dynamics separately [

28,

29]. Few studies have combined these perspectives to investigate the sharing behavior on social media. The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) provides a useful framework for understanding this behavior, emphasizing that attitudes and subjective norms shape individuals’ intentions, which in turn influence their behavior [

30]. Social Influence Theory further explores the role of compliance (subjective norm), internalization (group norm), and identification (social identity) in shaping behavior [

4,

31]. However, empirical applications of these theories to social media sharing behavior in tourism remain rare [

29].

Another relevant framework is Perceived Value Theory, which reflects the total benefit that a consumer perceives in a product or service, considering the balance between expenses and advantages [

32]. Although perceived value is a key factor in understanding user behavior and technology acceptance [

33], few studies have applied this theory to explore travel experience-sharing on social media [

33,

34].

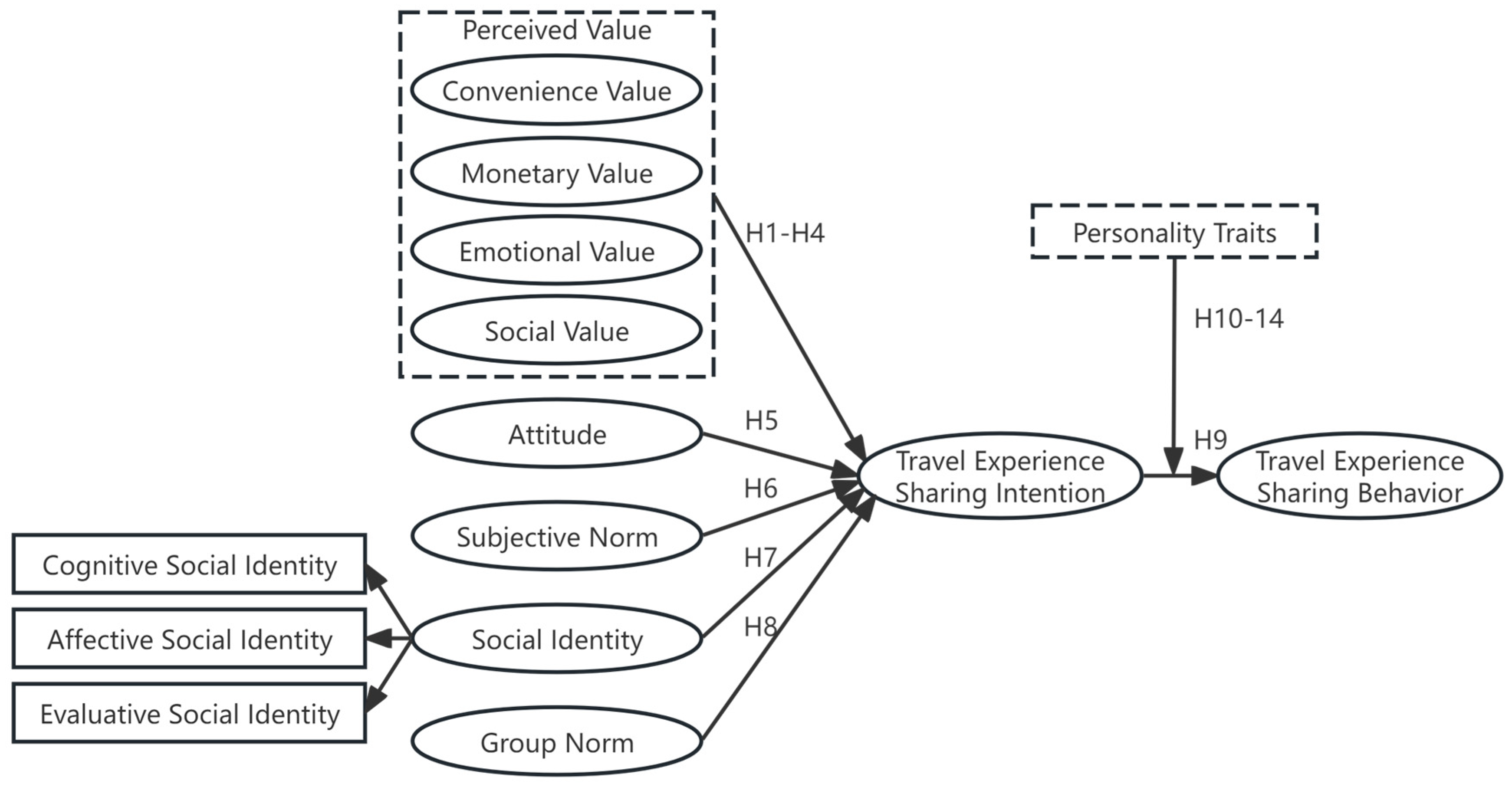

To address these gaps, the objectives of this study are: first, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing Chinese tourists’ behavior in sharing travel experiences on social media; second, to examine how internal motivations, including attitudes and subjective norms from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), as well as perceived value dimensions—convenience, emotional, monetary, and social values—impact tourists’ intentions to share their experiences, using Perceived Value Theory; third, to examine how external social pressures, such as social identity and group norms, influence tourists’ intentions to share their experiences by integrating Social Influence Theory to explain these effects; fourth, to explore the moderating role of personality traits such as openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism on the intention-behavior relationship; and finally, to provide insights for effective tourism marketing strategies and government policies by understanding how internal motivations, social influences, and personality traits shape sharing behaviors on social media.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perceived Value Theory

Perceived value refers to the overall assessment of the utility of a product or service based on the perception of what is gained versus what is sacrificed [

32]. In the context of travelers sharing their experiences on social media, perceived value reflects how the benefits of engaging in this activity (such as convenience, monetary rewards, social approval, and emotional satisfaction) are weighed against the effort or costs involved. Perceived value has been recognized as a key factor influencing consumer behavior, particularly in online settings. For example, research suggests that perceived value plays a significant role in influencing individuals’ intent to use online services [

27,

30]. In the case of travel experiences, the perceived value may vary across different dimensions, including convenience, monetary incentives, social status, and emotional satisfaction [

35]. Although previous studies have explored the individual dimensions of Perceived Value Theory, they often overlook how these dimensions interact with one another, resulting in a limited understanding of travelers’ sharing behavior. This study integrates these value dimensions with TRA and Social Influence Theory, providing a comprehensive framework that incorporates both internal motivations (e.g., attitudes and perceived value) and external pressures (e.g., social norms and group influences), offering a more nuanced explanation of the motivations driving travelers’ sharing behavior. This integrated approach addresses gaps in prior research that treated these theories separately.

2.1.1. Convenience Value

The development of digital communication has greatly changed the way people share experiences on social media platforms. Individuals’ perception of the convenience value of social media usage can affect their habits and behaviors on these platforms. In this context, it is particularly important to explore how convenience value affects tourists’ behavior in sharing trip experiences on social media. Prior studies have highlighted convenience value as a significant determinant of consumer intention to utilize online products or services [

27,

30,

35,

36]. When it comes to information search and dissemination on social media, convenience may play a crucial role as they represent low-effort channels for accessing and distributing information [

37].

Moreover, convenience is a key factor when it comes to sharing trip information on social media [

30,

38,

39]. Some scholars replaced perceived ease of use with effort expectancy, finding that it significantly affects travelers’ intent to share reviews online [

27]. In [

22] the authors showed that travelers’ intention to disseminate their experiences on social media is impacted by how easy those platforms are considered to use.

In China, the digital landscape presents a unique ecosystem with platforms like WeChat, Douyin (TikTok’s Chinese counterpart), and Red offering distinct sharing capabilities. The convenience value of these platforms plays a crucial part in facilitating travelers to share their experiences online [

40]. Therefore, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H1: Convenience value has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.1.2. Monetary Value

Research has shown a positive correlation between economic rewards and individuals’ willingness to engage on social media platforms [

30,

41]. For example, some scholars have discovered that the monetary value of the user had an impact on the perceived value, which was the most significant determinant of the intent to continue using live streaming services [

33]. In addition, other scholars have discovered similar results in their study. They discovered that people are encouraged to share reviews online when they receive economic rewards like bonus points, incentives, monetary rewards, giveaways, discounts, and prize distribution [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

However, the authors examined the determinants of current and future usage behaviors of video streaming services among Canadian millennials and showed that monetary value does not significantly affect current use of video streaming but significantly affects intent to use it in the future [

35]. This result is consistent with earlier studies [

34], which explored the impact of perceived consumer value and self-identity on the recommendation and use of streaming apps among U.S. college students, showing that perceived monetary value had no significant impact on the rate of use of streaming apps and that the perceived monetary value of streaming applications did not significantly influence the likelihood of recommending them to others.

Surprisingly, there is a negative correlation between economic rewards and tourists’ willingness to share comments on social media. The authors revealed that economic rewards negatively impact tourists’ intent to share reviews online [

27]. This may be because rewards indicate external control, leading individuals with strong intrinsic drives to view them as obligations and gradually lose interest in such behaviors [

42]. This contradiction in the literature highlights the need for a more nuanced exploration of how different motivations—intrinsic versus extrinsic—interact to influence travel-sharing behavior. Hence, based on the arguments, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H2: Monetary value has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.1.3. Emotional Value

Emotional value in the tourism sector has also garnered considerable attention. With respect to social media sharing of travel experiences, some scholars analyzed how the emotional value derived from disseminating trip experiences on social media was associated with revisiting intentions [

46]. Their results suggested that social media could help to develop an emotional bond with the destination, leading to a higher likelihood of revisiting. In addition, scholars have explored factors that affect the continued use of social media and the intention to share information among Korean tourists [

47]. The findings indicated that entertainment motivation had a substantial favorable impact on the continued use of social media and the intention of Korean tourists to disseminate trip information on social media. They argued that posting comments, videos, photos, and/or information online can provide consumers with relaxation and fun. Some scholars explored the motivations and technology acceptance factors influencing travelers’ intention to share reviews online, finding that hedonic motivation significantly impacts tourists’ desire to publish online reviews [

27].

Moreover, the author discovered that perceived enjoyment was a crucial element of users’ intent to disseminate travel photos in WeChat [

48]. This study highlighted the effect of perceived entertainment in encouraging people to disseminate their trip experiences on the WeChat platform. Tourists found it pleasurable, funny, and entertaining to use WeChat to share photos from their trips. Some researchers investigated the elements that drive travelers to continue sharing knowledge in the USA, UK, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates [

25]. Their findings confirmed the assumption that the impact of enjoyment in assisting others had a bigger impact on information sharing in online travel networks in developing countries than in developed countries. The enjoyment derived from assisting others has a substantial and immediate impact on changing the attitude towards the continuance of knowledge sharing. Hence, based on the arguments, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H3: Emotional value has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.1.4. Social Value

Existing research has shown that social value is a crucial component influencing users’ behavior on social media platforms. For instance, some scholars conducted an analysis of the many aspects that impact the ongoing utilization of live streaming services in India, and the study’s findings revealed that the social value of the user had an impact on the perceived value, which was the most significant determinant of the intent to continue using live streaming services [

33]. Additionally, the authors studied the determinants of current and future usage behavior of video streaming services by Canadian millennials, while the findings demonstrated that social value significantly and positively affects the prominence of one’s identity [

35]. However, this is different from previous research [

34], whose results indicate that social value is not significantly related to identity prominence. This could be attributed to the growing prevalence of streaming platforms, and social value may become more important in influencing video stream usage. This indicates that the dimension is not consistently important in digital settings [

49,

50]. This inconsistency suggests that the impact of social value may vary across contexts and platforms, a relationship that has not been sufficiently explored in the tourism context. Hence, based on the arguments, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H4: Social value has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.2. Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)

While Perceived Value Theory helps explain why individuals are motivated to share their experiences, TRA provides a more in-depth framework to understand how these motivations translate into actual behavior. The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) is regarded as a very significant and widely utilized social psychological theory [

51]. Initially proposed by Martin Fishbein in the 1960s [

52], TRA was refined and developed with Icek Ajzen in the 1970s [

53]. TRA was the first attempt to predict an individual’s behavior from their behavioral intention and pre-existing attitudes. It was formulated to produce a systematic framework to combine research on attitudes and behavior [

54]. TRA suggests that the primary factor influencing behavior is the individual’s intention to perform the behavior, which is determined by two key elements: attitude and subjective norm.

Attitude refers to a person’s positive or negative evaluation of performing a specific behavior [

54]. Behavioral beliefs inform this attitude, assessing the likelihood and value of engaging in the behavior. Subjective norms, on the other hand, reflect the perceived social pressure from significant others, like family and peers, influencing behavior [

54]. These normative beliefs drive individuals to conform to expectations, shaping their intentions and, consequently, their behavior.

TRA has been validated as an effective predictor of behavior across various domains, such as social networking [

55], tourism [

56], and news sharing [

57]. However, TRA assumes that behavior is under volitional control, which may not always be the case, as habitual or unconscious behaviors fall outside its scope [

57]. Although TRA has proven effective in predicting behavioral intentions, it overlooks external factors like social influence and perceived value, which can significantly affect travelers’ decision-making. To address these limitations, this paper integrates TRA with Perceived Value Theory and Social Influence Theory, offering a holistic view of travelers’ sharing behavior that incorporates both internal motivations (attitudes, perceived value) and external pressures (social norms, group influences).

2.2.1. Attitude

Previous studies on sharing tourism experiences have also illuminated the importance of attitude. Some studies have verified that tourists’ attitudes influence their decision to disseminate their tourism experiences on social media [

22]. For instance, the authors discovered that tourists were more inclined to disseminate their experiences on social media when they gained greater enjoyment from publishing reviews on social media [

27]. Furthermore, other scholars found a significant correlation between travelers’ attitudes and their willingness to continue disseminating travel knowledge online, as well as their continued dissemination behavior [

25]. These findings suggest that a positive attitude enhances the intention to share travel experiences. Thus, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H5: Attitude has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.2.2. Subjective Norm

The first social influence model described by subjective norm is akin to the term “compliance” proposed by [

31]. Subjective Norm refers to the opinions of other groups of people, including friends and family, that might influence one’s behavior [

54]. Individuals’ behavior is shaped by the expectations of referent others and the extent to which they anticipate complying with these expectations [

58]. This highlights the role of societal pressure in shaping individual behaviors across diverse contexts.

Existing research has empirically verified the direct impact of subjective norms on people’s willingness to disseminate travel knowledge on social media [

30]. For example, some researchers found that subjective norms significantly influenced the belief in the integrity of travel-related online social network websites. This belief in integrity significantly affected users’ intent to disseminate travel knowledge within these websites [

30]. Therefore, subjective norms play a crucial role in shaping travelers’ sharing intentions. Hence, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H6: Subjective norm has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.3. Social Influence Theory

TRA has been widely used in understanding behaviors in online settings, but it often fails to capture the complexity of sharing behaviors on social media, especially when multiple motivations are involved. To address this limitation, this study will integrate the Social Influence Theory proposed by Kelman [

59] has been widely recognized as a foundational framework for understanding psychological commitment to certain attitudes or behaviors [

60,

61]. According to this theory, an individual’s behavior change can be caused by social influence at three distinct stages: compliance, identification, and internalization. These stages reflect various commitments resulting from the pursuit of different objectives [

59]. Individuals’ proactive choices in accordance with their own values and beliefs drive these stages of psychological attachment [

60]. In the context of tourism behavior, these stages help explain how travelers transition from externally motivated sharing (compliance) to more internalized motivations such as group belonging and personal values. However, most existing studies treat these constructs in isolation and fail to connect them with broader decision-making frameworks such as TRA or motivational theories like Perceived Value Theory.

Compliance occurs when individuals engage in behaviors to gain approval or avoid disapproval from others. These behaviors are performed primarily due to external pressures or societal expectations rather than aligning with personal values [

59]. This form of influence may trigger initial sharing behavior on social media but often lacks sustainability unless reinforced by deeper motivational factors such as identification or value alignment. Identification happens when individuals adopt behaviors to create or maintain a fulfilling relationship with another individual or group, driven by a desire to belong to or be accepted by that group [

59]. Finally, internalization occurs when an individual accepts influence because the behavior aligns with their personal values and provides inherent rewards. The behavior then becomes an integral part of their own norms and is sustained independently of external pressures [

59,

60].

Kelman identified three processes of social influence: subjective norms, social identity, and group norms [

31], which have been used in many studies [

29,

62,

63]. Subjective Norm refers to the opinions of other groups of people, including friends and family, that might influence one’s behavior [

54]. Social identity refers to one’s self-concept in relation to a group [

29,

62], while group norms reflect the collective expectations within a group [

29].

The concept of social influence has been widely used to explain group behavior and is increasingly applied in consumer behavior studies, such as understanding students’ use of desktop services [

63] and the role of social norms in energy conservation [

64]. In the context of tourism, Social Influence Theory has been employed to explore travelers’ sharing behaviors on social media [

4,

65]. Studies have shown that identification, internalization, and compliance significantly affect travelers’ enjoyment and willingness to share their experiences online, with perceived enjoyment being a key motivator for continued sharing behavior.

Thus, Social Influence Theory provides a comprehensive lens through which to study the dissemination of tourism experiences on social media, especially among Chinese travelers.

2.3.1. Social Identity

The second social influence model delineated by social identity is akin to the concept of “identification” proposed by Kelman [

31]. Social identity has emerged as a valuable variable that guides the influence process [

66]. It underscores how a person’s identification with a particular social group can influence their behavior and decision-making. When individuals see themselves as part of a group, they are more likely to engage in group-related actions [

29,

62,

63].

In existing literature, some scholars have applied social identity to the context of studying tourism experience-sharing [

4,

65]. Travelers often perceive posting travel information on social media as an extension of their personality, integrating it into their self-presentation on these platforms [

4]. This implies that social identity significantly influences sharing behavior, especially among those who closely identify with traveler communities on social media. Thus, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H7: Social identity has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.3.2. Group Norm

The third social influence model, delineated by group norms, aligns with the concept of ‘internalization’ proposed by Kelman [

31]. Group norms refer to a common agreement within a group regarding their collective expectations and goals [

29]. User engagement in online communities is substantially determined by group norms since it denotes information that is associated with a certain group and will influence interactions among members [

67]. When individuals align their goals and values with those of the group, their willingness to participate increases [

29].

In the context of tourism experience-sharing, some scholars have also examined the effect of group norms on tourists’ behavior in disseminating trip experiences. For instance, Kang and Schuett [

65] used the three constructs of Social Influence Theory, including identification, internalization, and compliance, to explore the factors influencing travelers’ dissemination of their trip experiences on social media. Findings indicated that compliance (group norms) negatively impacted perceived knowledge enjoyment and the dissemination of real-life travel experiences on social media. In the subsequent study, Oliveira, Araujo, and Tam [

4] used the three constructs of Social Influence Theory to investigate why travelers are eager to post their travel memories on social media, and the results showed that compliance (group norms) negatively impacted travelers’ perceived enjoyment and that perceived enjoyment was the primary significant motivation for travelers to post their trip experiences on travel websites. These studies suggest the nuanced role of group norms in shaping travelers’ sharing intentions. By integrating group norms with TRA, this study demonstrates how internalized group expectations shape travelers’ sharing intention. Moreover, when travelers perceive alignment between group values and personal benefits, they are more likely to act upon group norms, revealing a new link between value perception and group influence. Therefore, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H8: Group norm has a positive impact on travelers’ intention to share their travel experience.

2.4. Travel Experience-Sharing Behavior

According to TRA, the primary factor influencing one’s behavior is their intent to engage in that behavior [

68]. In the research on tourism experience-sharing, scholars have also verified that travelers’ intent to disseminate experiences on social media positively affects their sharing behavior [

27,

29]. For instance, when travelers have a strong intent to disseminate their trip experiences, this intention often translates into actual sharing behavior on social media, such as posting photos, videos, or reviews.

Scholars have also confirmed that travelers’ intention to continue sharing information online has a positive and direct impact on their behavior of continuing to share information [

25]. Similarly, studies in China have validated the significant impact of intention on sharing behavior [

69]. Hence, this study puts forth the following hypothesis:

H9: Travelers’ intention to share their travel experience has a positive impact on their behavior to share their travel experience.

2.5. Moderating Role of Personality Traits

Maddi defined personality as a consistent collection of traits and inclinations that distinguished how individuals thought, felt, and acted [

70]. The five personality models categorize traits into five dimensions: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism [

71], which shape individuals’ behaviors in different contexts [

72]. For instance, Amiel and Sargent found that individuals with distinct personality traits exhibited distinct internet usage behaviors [

73]. Li and Chignell argued that personality traits were significant driving factors in how people interacted with UGC [

74]. Moore and McElroy found that personality traits could account for the content that individuals posted on Facebook and the manner in which they used the platform [

75].

Moreover, personality traits have been found to moderate motivational factors influencing the creation of UGC [

76], and personality traits may serve as an incentive for individuals to compose online evaluations [

76,

77]. Furthermore, some scholars found that certain personality traits could moderate the relationship between motivational factors and UGC involvement [

24]. For example, traits such as extroversion and agreeableness significantly influence UGC participation in Spain, while in China, agreeableness and neuroticism also play a role [

24]. This suggests that personality traits may serve as a moderating variable between motivational drivers and behaviors in digital contexts. Thus, personality traits are pivotal in shaping both the intention and the behavior of sharing travel experiences. Based on these arguments, this study puts forth the following hypotheses:

H10: Travelers’ openness to experience will moderate the relationship between travelers’ intention to share their travel experiences and their behavior to share their travel experiences.

H11: Travelers’ conscientiousness will moderate the relationship between travelers’ intention to share their travel experiences and their behavior to share their travel experiences.

H12: Travelers’ extraversion will moderate the relationship between travelers’ intention to share their travel experiences and their behavior to share their travel experiences.

H13: Travelers’ agreeableness will moderate the relationship between travelers’ intention to share their travel experiences and their behavior to share their travel experiences.

H14: Travelers’ neuroticism will moderate the relationship between travelers’ intention to share their travel experiences and their behavior to share their travel experiences.

The proposed research model is presented in

Figure 1. Research framework.

3. Methodology

Before conducting the survey, it was necessary to examine the demographic distribution of the target sample. Based on the 54th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China published by CNNIC, as of June 2024, individuals aged 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, and 40–49 accounted for 13.6%, 13.5%, 19.3%, and 16.7% of the total internet users in China, respectively. These figures emphasize the prominent presence of younger and middle-aged individuals in the Chinese online community, underscoring their importance as a key demographic for research on social media usage.

The survey questionnaire was developed by adapting established scales from previous research on social media usage and travel behavior. Key constructs, such as convenience value [

33], monetary value [

27,

78], social value [

33], emotional value [

33], attitude [

79,

80], subjective norm [

81], social identity [

62,

82], group norm [

63], travel experience-sharing intention [

47,

83], travel experience-sharing behavior [

15], and personal traits [

84,

85], were included in the questionnaire. These constructs were measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ensuring both reliability and validity. The questionnaire underwent a pre-test to ensure clarity, and adjustments were made accordingly.

This study adopted a stratified random sampling approach based on age to distribute the survey link, targeting participants aged 18 and above. A purposive sampling method was employed to recruit Chinese travelers who have shared their travel experiences on social media. Specifically, participants were required to meet three criteria: (1) having an active social media account (e.g., WeChat, QQ, Douyin, Red, etc.), (2) having traveled within the past 18 months, and (3) having shared travel-related content (e.g., comments, photos, or videos) on their social media accounts.

The survey was shared online via WeChat and QQ, two of the most popular social media platforms in China, reaching participants through relevant online communities and social media networks. A snowball sampling method was also employed, where participants were encouraged to share the survey with others. Data collection took place between January and February 2024, yielding 675 responses. After excluding incomplete or invalid responses, 489 valid responses were retained for analysis.

SPSS 27.0 and SmartPLS 4.0 were utilized to conduct the data analysis. The choice of PLS-SEM over CB-SEM is based on several factors aligned with the objectives and characteristics of this study. While CB-SEM is suitable for theory testing in well-established models with large sample sizes and normally distributed data, PLS-SEM is preferred for exploratory research aiming to predict key constructs and identify underlying relationships [

86,

87,

88]. It is also more flexible in handling non-normal data and well-suited for models involving multiple constructs and interactions, which are central to this research.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

Table 1 shows that 69.5% of the respondents are female, while 30.5% are male. The majority of respondents (31.3%) are aged 18–24 years, followed by 26.8% in the 25–34 age group. This highlights that younger individuals dominate the sample, which may reflect a higher engagement with social media platforms for sharing travel experiences. In terms of education, over half of the respondents (70.1%) hold a bachelor’s degree, which may indicate a higher level of education among those who engage in social media-driven behaviors such as travel-sharing. Furthermore, 81.2% of respondents have shared their travel experiences on social media, demonstrating that the majority are actively involved in online travel-sharing, which could be linked to their social media engagement. In terms of monthly income, the largest group (27.8%) earns between 5001 and 10,000 RMB, which may also be reflective of typical social media users who can afford leisure travel. Regarding daily social media usage, the majority (50.3%) spend 1–4 h on social media each day, followed by 31.1% who spend 5–8 h daily. This suggests that respondents are highly engaged with social media, which could explain their frequent travel-sharing behavior, as more time spent on social media increases the likelihood of sharing personal experiences.

4.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

To assess the reliability of the constructs, Cronbach’s alpha (α) values were examined. As shown in

Table 2, all constructs exhibited Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.702 to 0.952, which are above the recommended threshold of 0.700, indicating satisfactory internal consistency [

89]. This suggests that the measurement items are reliably measuring the same underlying construct. Similarly, the composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.858 to 0.974, all exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.700, further confirming the reliability of the measurement model. These results collectively indicate that the constructs in this study are internally consistent and reliable.

For convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs was greater than the threshold of 0.500, ranging from 0.676 to 0.950. These results indicate that each construct accounts for more than 50% of the variance in its indicators, demonstrating adequate convergent validity [

89]. This suggests that the constructs are well-defined and that their indicators are measuring the intended concepts effectively.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT). As shown in

Table 3, most HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.85 [

90]. However, the value between ASI and ESI (0.866) marginally exceeded this threshold. This slight exceedance is theoretically justified, given the conceptual overlap between these constructs as social identity subdimensions. Recent guidelines suggest that a value of 0.90 is acceptable for related constructs [

88,

89]. All other values remained below 0.85, supporting the conclusion of discriminant validity.

In conclusion, the reliability and validity assessments indicate that the measurement model is robust, providing a solid foundation for the evaluation of the structural model.

4.3. Assessment of Structural Model

As presented in

Table 4, the structural model reveals significant effects across various constructs. Convenience value (β = 0.122, t = 2.485,

p < 0.05), emotional value (β = 0.095, t = 2.842,

p < 0.01), attitude (β = 0.147, t = 2.161,

p < 0.05), subjective norm (β = 0.154, t = 2.090,

p < 0.05), social identity (β = 0.242, t = 3.692,

p < 0.001), and group norm (β = 0.205, t = 4.023,

p < 0.001) all showed significant positive effects on travel experience-sharing intention. Therefore, H1, H3, H5, H6, H7, and H8 are supported. However, Monetary Value (β = −0.035, t = 0.614,

p > 0.05) and Social Value (β = 0.085, t = 1.588,

p > 0.05) did not significantly influence travel experience-sharing intention, resulting in the rejection of H2 and H4. Moreover, travel experience-sharing intention significantly impacted travel experience-sharing behavior (β = 0.381, t = 6.453,

p < 0.001), confirming H9.

Turning to

Table 5 on the moderated mediation results, the moderation effects were examined, and several hypotheses were confirmed. The analysis reveals that openness (β = 0.127, t = 2.412,

p < 0.05), agreeableness (β = 0.405, t = 8.461,

p < 0.001), and conscientiousness (β = 0.441, t = 7.623,

p < 0.001) significantly moderated the relationship between travel experience-sharing intention and travel experience-sharing behavior, thereby supporting H10, H12, and H14. However, neuroticism (β = −0.005, t = 0.107,

p > 0.05) and Extraversion (β = 0.001, t = 0.021,

p > 0.05) did not show significant moderating effects, leading to the rejection of H11 and H13.

5. Discussion and Implications

This study enhances our understanding of travel experience-sharing behavior on social media by integrating Perceived Value Theory, Theory of Reasoned Action, and Social Influence Theory. The findings show that convenience value, emotional value, attitude, subjective norm, social identity, and group norm significantly influence travel experience-sharing intention, while monetary value and social value do not exhibit significant effects. These results provide important theoretical and practical insights into the factors shaping online sharing behaviors, particularly among Chinese travelers.

Convenience value is a key predictor of sharing intention, aligning with research emphasizing ease and flexibility in online behaviors [

91]. Travelers value the ability to share content across platforms, highlighting the importance of seamless functionality in tourism digital platforms [

92]. This suggests that businesses should prioritize improving user experience, optimizing interfaces, and ensuring seamless sharing across devices, making the process more accessible and efficient.

Emotional value significantly impacts sharing intention, reinforcing the role of emotional engagement in consumer behavior [

93]. Sharing travel experiences evokes positive emotions, such as excitement and satisfaction, motivating individuals to participate in social media interactions. Marketers should design experiences that elicit strong emotional responses, particularly those involving self-discovery or cultural immersion, as these will likely foster a deeper connection with the content and encourage sharing.

Attitude and subjective norms also significantly influence sharing intention, supporting the Theory of Reasoned Action [

53]. A favorable attitude toward sharing and the perceived expectations of friends, family, and peers drive sharing behaviors. In collectivist cultures like China, where social harmony is valued [

94], tourism campaigns should emphasize social approval and peer recognition to motivate sharing.

Social identity and group norms also affect sharing intention, consistent with Social Influence Theory [

43]. Travelers who identify with a social media community are more likely to share their experiences. Creating branded travel experiences that emphasize group participation and social connection can strengthen communities, encouraging travelers to share their stories.

While monetary and social value did not significantly impact sharing intention, this result aligns with some earlier studies [

33,

34] but contrasts with others, suggesting that extrinsic rewards, such as monetary incentives and social value, can positively influence sharing behaviors [

4,

44]. The lack of significant effect in this study may be due to cultural or contextual differences, particularly among Chinese consumers, where intrinsic motivations like emotional engagement and social identity may be more influential [

95]. Additionally, extrinsic rewards sometimes decrease intrinsic motivation, especially when the task is already inherently enjoyable or interesting [

96]. Consequently, marketers should focus on fostering intrinsic motivations by creating emotionally engaging experiences rather than relying on external rewards.

The moderation analysis reveals that personality traits significantly influence the relationship between intention and behavior. Specifically, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness are key moderators, suggesting that individuals with these traits are more likely to act on their intention to share. Openness reflects a desire for new experiences and exploration, while agreeableness and conscientiousness enhance social connection and foster responsibility, respectively. These findings suggest that marketers can segment their target audience based on these personality traits and tailor campaigns accordingly.

In contrast, neuroticism and extraversion did not significantly moderate the relationship between intention and behavior, highlighting the complex interplay between personality traits and sharing behavior. Marketers should prioritize traits that directly influence sharing, such as openness and agreeableness, when designing campaigns.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature by integrating Perceived Value Theory, the Theory of Reasoned Action, and Social Influence Theory to explain travel experience-sharing behaviors. The findings confirm the importance of convenience value, emotional value, subjective norm, and group norm in shaping sharing intentions, highlighting the relevance of intrinsic motivations and social influences in online sharing behavior. The non-significant effects of monetary value and social value suggest that external rewards and perceived peer status are less critical drivers in this context, consistent with Walsh and Singh [

35], who found a limited influence of social value and monetary rewards on current behaviors. Additionally, economic rewards may even negatively affect tourists’ intention to share reviews online, highlighting the greater importance of intrinsic motivations [

27].

The study also provides insights into the moderating role of personality traits. Openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness significantly enhance the relationship between intention and behavior, demonstrating the importance of individual differences in shaping sharing behavior [

97]. In contrast, neuroticism and extraversion do not have significant moderating effects, indicating their limited role in this context.

By focusing on Chinese travelers, this research adds a cross-cultural perspective, showing how social norms and group identity influence sharing intentions. This study deepens the theoretical understanding of travel experience-sharing and provides a basis for future research to explore personality and cultural factors in other social media contexts.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Even though not all tourism experiences need to emphasize the factors driving travel experience-sharing, tourism service providers should focus on key elements such as convenience and emotional value. These factors significantly influence travelers’ willingness to share their experiences on social media. Tourism businesses should prioritize convenience by enhancing digital platforms that allow seamless sharing across social media platforms, ensuring that the sharing process is simple and accessible, making it easier for travelers to share their stories.

In addition to convenience, creating emotional connections through memorable and meaningful experiences is essential for encouraging travelers to share their stories. Social identity and group norms also play a role in sharing intentions, as travelers who identify with a community are more likely to share their experiences. Tourism marketers, destination managers, and social media platforms can tap into these motivations by designing branded travel experiences that foster group participation and social connections, further motivating travelers to share their stories and engage with their communities.

Moreover, understanding personality traits such as openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness is crucial for designing effective marketing strategies. Tailoring campaigns to travelers’ psychological profiles will increase the likelihood of sharing.

Governments can also support these efforts by promoting policies that encourage the development of platforms that prioritize convenience, security, and social engagement. These platforms should facilitate sharing behavior and enhance user engagement [

22], addressing the growing need for seamless digital interactions in the tourism sector. Furthermore, policy initiatives that promote the development of tourism experiences aligning with emotional values and group norms can enhance community engagement and encourage positive social interactions through shared travel experiences. Promoting such initiatives will not only foster stronger community engagement but also ensure the sustainable growth of tourism.

6. Limitations and Future Studies

This study has several limitations that future research should address. First, the focus on Chinese travelers limits the generalizability of the findings to other regions. Future studies could expand to different cultural contexts, such as Western or other Asian countries, to compare travel experience-sharing behaviors and understand how cultural norms influence online sharing practices. Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases, such as social desirability or recall bias. To mitigate these issues, future studies should incorporate observational or experimental methods for validation, such as tracking actual sharing behaviors on social media platforms.

While this study explored convenience, emotional, and social value, other factors—such as intrinsic motivations and platform-specific influences—warrant further investigation. Future research could examine how different social media platforms (e.g., WeChat vs. Instagram) and content types (e.g., images vs. reviews) influence sharing behavior.

In terms of age, prior research shows that different age groups exhibit distinct sharing behaviors [

98]. Age, as a demographic factor, has been shown to influence travelers’ social media sharing [

99]. However, few studies have explored age as a moderator in travel-sharing behaviors. Future studies should examine how age moderates the relationship between sharing intention and behavior, considering generational differences in social media usage and content-sharing patterns [

15]. This would help clarify how younger and older generations differ in their motivations and practices around online sharing.

Additionally, the current sample is predominantly young and collected via WeChat and QQ, which may introduce sample bias. Future studies should consider diversifying the sample by including participants from other age groups and platforms, such as Douyin and Red, to enhance the generalizability of the results.

Lastly, future research should investigate actual sharing behavior by observing online content-sharing activities across platforms to bridge the gap between intention and behavior. This could involve a mixed-methods approach, combining survey data with real-time tracking of content-sharing to provide a more comprehensive understanding of online sharing behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and N.M.I.; methodology, C.C., N.M.I. and N.S.; software, C.C.; validation, C.C., N.M.I. and N.S.; formal analysis, C.C.; investigation, C.C.; resources, C.C. and N.M.I.; data curation, C.C. and N.M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, C.C., N.M.I. and N.S.; visualization, C.C.; supervision, N.M.I. and N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Statement was assigned by the Universiti Utara Malaysia (18 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, T.B.J.; Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M.S. Sharing Travel Related Experiences on Social Media—Integrating Social Capital and Face Orientation. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Béal, L.; Zaman, M.; Hall, C.M.; Rather, R.A. How Does Sharing Travel Experiences on Social Media Improve Social and Personal Ties? Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 3478–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Sharing Tourism Experiences: The Posttrip Experience. J. Travel. Res. 2017, 56, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Araujo, B.; Tam, C. Why Do People Share Their Travel Experiences on Social Media? Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keelson, S.A.; Bruce, E.; Egala, S.B.; Amoah, J.; Bashiru Jibril, A. Driving Forces of Social Media and Its Impact on Tourists’ Destination Decisions: A Uses and Gratification Theory. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2318878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Park, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The Role of Smartphones in Mediating the Touristic Experience. J. Travel. Res. 2012, 51, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, L.; Li, X. Social Media Envy: How Experience Sharing on Social Networking Sites Drives Millennials’ Aspirational Tourism Consumption. J. Travel. Res. 2019, 58, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Masui, F.; Eronen, J.; Terashita, S.; Ptaszynski, M. A New Approach to Extracting Tourism Focus Points from Chinese Inbound Tourist Reviews after COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Will People Travel Because of Envy? The Influence of Travel Experience Sharing on the Post-90s WeChat Users. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2833–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.W.C.; Lai, I.K.W.; Tao, Z. Sharing Memorable Tourism Experiences on Mobile Social Media and How It Influences Further Travel Decisions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1773–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Tosun, C.; Mohamed, A.E.; Uslu, S. The Influence of Social Media Usage and Perceived Government Market Orientation on Travel Intention to an Internet Celebrity City: Exploring the Mediating Effects of Place Attachment and Perceived Value. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, F.P.; Pontes, N.; Schivinski, B. Influencer Marketing Effectiveness: Giving Competence, Receiving Credibility. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluri, A.; Slevitch, L.; Larzelere, R. The Effectiveness of Embedded Social Media on Hotel Websites and the Importance of Social Interactions and Return on Engagement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Sotiriadis, M.; Zhou, Q. Could Smart Tourists Be Sustainable and Responsible as Well? The Contribution of Social Networking Sites to Improving Their Sustainable and Responsible Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arica, R.; Cobanoglu, C.; Cakir, O.; Corbaci, A.; Hsu, M.J.; Della Corte, V. Travel Experience Sharing on Social Media: Effects of the Importance Attached to Content Sharing and What Factors Inhibit and Facilitate It. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1566–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M.D. Sharing Tourism Experiences in Social Media: A Literature Review and a Set of Suggested Business Strategies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 179–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vega, R.; Taheri, B.; Farrington, T.; O’Gorman, K. On Being Attractive, Social and Visually Appealing in Social Media: The Effects of Anthropomorphic Tourism Brands on Facebook Fan Pages. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Impact of Short Video Marketing on Tourist Destination Perception in the Post-Pandemic Era. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Tussyadiah, I.; Miller, G. That’s Private! Understanding Travelers’ Privacy Concerns and Online Data Disclosure. J. Travel. Res. 2021, 60, 1510–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J. The Relative Impact of User-and Marketer-Generated Content on Consumer Purchase Intentions: The Case of the Social Media Marketing Platform, 0.8 L. In Proceedings of the International Association of Societies of Design Research Conference, Manchester, UK, 2–5 September 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- PowerReviews. How User-Generated Visual Content Impacts Purchase Behavior; PowerReviews: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Sharing Tourism Experiences in Social Media: A Systematic Review. Anatolia 2024, 35, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNNIC. The 54th Statistical Report on the Development Status of the Internet in China; CNNIC: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Bilgihan, A.; Shi, F.; Okumus, F. UGC Involvement, Motivation and Personality: Comparison between China and Spain. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H.; Eid, R.; Agag, G.; Shehawy, Y.M. Cross-National Differences in Travelers’ Continuance of Knowledge Sharing in Online Travel Communities. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.G. Putting the “Self” in Selfies: How Narcissism, Envy and Self-Promotion Motivate Sharing of Travel Photos through Social Media. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.; Dogra, N.; Gupta, A. WHat Motivates Posting Online Travel Reviews? Integrating Gratifications with Technological Acceptance Factors. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 25, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, Y.S.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.G. The Effects of Individual Motivations and Social Capital on Employees’ Tacit and Explicit Knowledge Sharing Intentions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Understanding Online Community User Participation: A Social Influence Perspective. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Consumer Perception of Knowledge-Sharing in Travel-Related OnlineSocial Networks. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Social Influence and Linkages between the Individual and the Social System: Further Thoughts on the Processes of Compliance, Identification, and Internalization. Perspect. Soc. Power. Chic. Aldine 1974, 1, 125–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Kalinić, Z.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J. Assessing Determinants Influencing Continued Use of Live Streaming Services: An Extended Perceived Value Theory of Streaming Addiction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, A.; Simpson, P.M. Streaming Apps: What Consumers Value. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.; Singh, R. Determinants of Millennial Behaviour towards Current and Future Use of Video Streaming Services. Young Consum. 2022, 23, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuseir, M.; Elrefae, G. The Effect of Social Media Marketing, Compatibility and Perceived Ease of Use on Marketing Performance: Evidence from Hotel Industry. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Septiansyah, M.A.L.; Sa’dullah, M.H.; Syaifuddin, S. Instagram as a Da’wah Medium for Al-Hasany Foundation Islamic Boarding School. KOMUNIKA J. Dakwah Dan. Komun. 2022, 16, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Seiders, K.; Grewal, D. Understanding Service Convenience. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiders, K.; Voss, G.B.; Grewal, D.; Godfrey, A.L. Do Satisfied Customers Buy More? Examining Moderating Influences in a Retailing Context. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of Social Media in Online Travel Information Search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-L.; Lai, C.-Y. Motivations of Wikipedia Content Contributors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Kim, Y.-G. Breaking the Myths of Rewards: An Exploratory Study of Attitudes about Knowledge Sharing. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. (IRMJ) 2002, 15, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasonikolakis, I.; Vrechopoulos, A.; Pouloudi, A. Store Selection Criteria and Sales Prediction in Virtual Worlds. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Wang, X.; Tan, C.-H.; Teo, H.-H. An Empirical Study of Information Contribution to Online Feedback Systems: A Motivation Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Al Nasser, A.; Hussain, Y.K. Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction of a UAE-Based Airline: An Empirical Investigation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 42, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.; Kim, T.T.; Karatepe, O.M.; Lee, G. An Exploration of the Factors Influencing Social Media Continuance Usage and Information Sharing Intentions among Korean Travellers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Understanding Chinese Tourists’ Motivations of Sharing Travel Photos in WeChat. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Any, A.A.; Winklhofer, H.; Ennew, C. Measuring Users’ Value Experience on a Travel Website (e-Value) What Value Is Cocreated by the User? J. Travel. Res. 2015, 54, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pura, M. Linking Perceived Value and Loyalty in Location-based Mobile Services. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2005, 15, 509–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.L.; Householder, B.J.; Greene, K.L. The Theory of Reasoned Action. Persuas. Handb. Dev. Theory Pract. 2002, 14, 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M. The Relationships between Beliefs, Attitudes and Behavior. In Cognitive Consistency, Motivational Antecedents and Behavioral Consequents; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Penn State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Peslak, A.; Ceccucci, W.; Sendall, P. An Empirical Study of Social Networking Behavior Using Theory of Reasoned Action. Journal of Information Systems Applied Research 2012, 5, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, S.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Residents’ Attitudes towards Tourism, Cost–Benefit Attitudes, and Support for Tourism: A Pre-Development Perspective. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2023, 20, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnowski, V.; Leonhard, L.; Kümpel, A.S. Why Users Share the News: A Theory of Reasoned Action-Based Study on the Antecedents of News-Sharing Behavior. Commun. Res. Rep. 2018, 35, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashotte, L. Social Influence. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Ritzer, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, Identification, and Internalization Three Processes of Attitude Change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Y.; Galletta, D. A Multidimensional Commitment Model of Volitional Systems Adoption and Usage Behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 117–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J. Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment: The Effects of Compliance, Identification, and Internalization on Prosocial Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. A Theoretical Model of Intentional Social Action in Online Social Networks. Decis. Support. Syst. 2010, 49, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M. Examining Students’ Continued Use of Desktop Services: Perspectives from Expectation-Confirmation and Social Influence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative Social Influence Is Underdetected. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Schuett, M.A. Determinants of Sharing Travel Experiences in Social Media. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; Rink, F. Identity in Work Groups: The Beneficial and Detrimental Consequences of Multiple Identities and Group Norms for Collaboration and Group Performance. Soc. Identif. Groups 2005, 22, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A Social Influence Model of Consumer Participation in Network-and Small-Group-Based Virtual Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding Consumer Intention to Participate in Online Travel Community and Effects on Consumer Intention to Purchase Travel Online and WOM: An Integration of Innovation Diffusion Theory and TAM with Trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Peng, L. A Moderated Mediation Model of Sharing Travel Experience on Social Media: Motivations and Face Orientations in Chinese Culture. J. China Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.R. Personality Theories: A Comparative Analysis; Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 0534205143. [Google Scholar]

- Farnadi, G.; Zoghbi, S.; Moens, M.-F.; De Cock, M. Recognising Personality Traits Using Facebook Status Updates. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Cambridge, MA, USA, 8–11 July 2013; Volume 7, pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, S.B.G.; Eysenck, H.J.; Barrett, P. A Revised Version of the Psychoticism Scale. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1985, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, T.; Sargent, S.L. Individual Differences in Internet Usage Motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2004, 20, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chignell, M. Birds of a Feather: How Personality Influences Blog Writing and Reading. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2010, 68, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; McElroy, J.C. The Influence of Personality on Facebook Usage, Wall Postings, and Regret. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensink, J.M. What Motivates People to Write Online Reviews and Which Role Does Personality Play. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.S.; Yao, S.S. What Makes Hotel Online Reviews Credible? An Investigation of the Roles of Reviewer Expertise, Review Rating Consistency and Review Valence. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.W.; Sanders, G.L.; Moon, J. Exploring the Effect of E-WOM Participation on e-Loyalty in e-Commerce. Decis. Support. Syst. 2013, 55, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Mahmood, K.; Islam, T. Understanding the Facebook Users’ Behavior towards COVID-19 Information Sharing by Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and Gratifications. Inf. Dev. 2023, 39, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.H.; Farhang, M.; Zolfagharian, M.; Hofacker, C.F. Predicting Value Cocreation Behavior in Social Media via Integrating Uses and Gratifications Paradigm and Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yin, J.; Song, Y. An Exploration of Rumor Combating Behavior on Social Media in the Context of Social Crises. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C. How to Unite the Power of the Masses? Exploring Collective Stickiness Intention in Social Network Sites from the Perspective of Knowledge Sharing. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Ma, L. News Sharing in Social Media: The Effect of Gratifications and Prior Experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.D. Psychometric Properties of Ten-Item Personality Inventory In. China J. Health Psychol. 2013, 21, 1688–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, N.; Xie, Q.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Meng, H. A Dual Perspective on Risk Perception and Its Effect on Safety Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Safety Motivation, and Supervisor’s and Coworkers’ Safety Climate. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 134, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: A Comparative Evaluation of Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling Methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity in PLS-SEM: A Multi-Method Approach. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Ringle, C.M. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet”–Retrospective Observations and Recent Advances. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2023, 31, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y. Tourism Destination Image Based on Tourism User Generated Content on Internet. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kandampully, J.; Bilgihan, A. The Influence of EWOM Communications: An Application of Online Social Network Framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Bai, B. The Effects of Photo-Sharing Motivation on Tourist Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Online Social Support. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Da-yong, Z.; Zhan, S. Short Video Users’ Personality Traits and Social Sharing Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1046735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.H.; Bae, S.Y. Roles of Authenticity and Nostalgia in Cultural Heritage Tourists’ Travel Experience Sharing Behavior on Social Media. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, M.S.; Lever, M.W.; Elliot, S. A Cross-National Comparison of Intragenerational Variability in Social Media Sharing. J. Travel. Res. 2020, 59, 1204–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).