Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Research Objectives

2.1. Research Objectives for the First Study

2.2. Research Objectives for the Second Study

2.3. Research Objectives for the Third Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology Used for the First Study: Focus Group Interviews

- The majority of respondents associate Brașov with tourism and the natural environment.

- The majority of interviewed students do not associate Brașov’s city brand with cultural events.

- Most respondents are not familiar with the city’s cultural offerings.

- The target audience believes that the local cultural offer is insufficient.

- The majority of young people think that cultural events in Brașov are insufficiently promoted.

3.2. Methodology Employed for the Second Study: In-Depth Interviews

- The majority of cultural operators believe that Brașov’s cultural brand is currently represented by the natural environment, the Old Town, and mountain activities. This hypothesis was formulated based on the results of qualitative research through group interviews.

- A large portion of respondents consider the local cultural infrastructure to be insufficient.

- The main issue faced by cultural operators in Brașov is the lack of consistent and predictable funding.

- Some event organizers do not believe that Brașov has a cultural brand.

3.3. Methodology for the Third Study: Quantitative Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Results for the First Qualitative Study (Focus Groups)

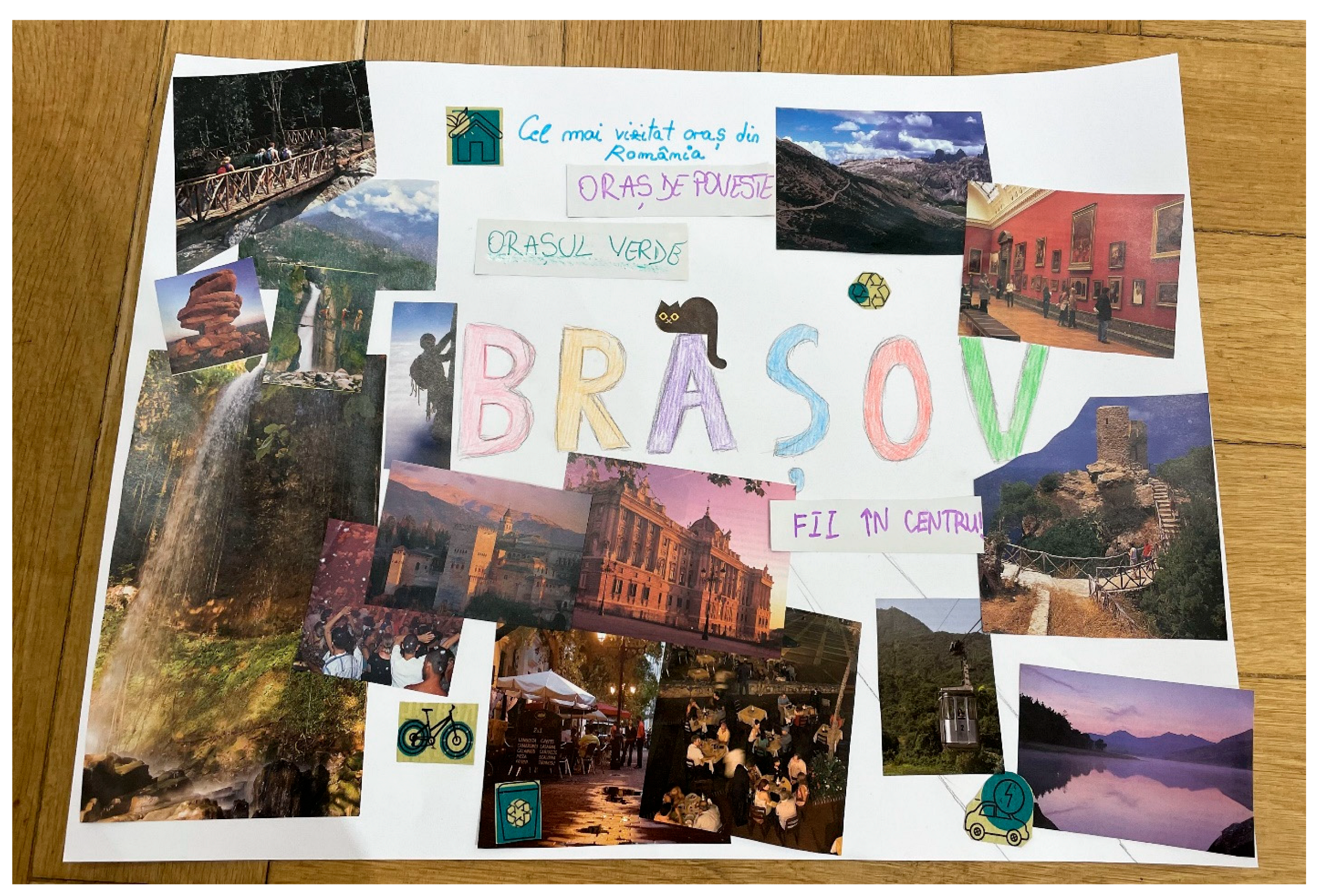

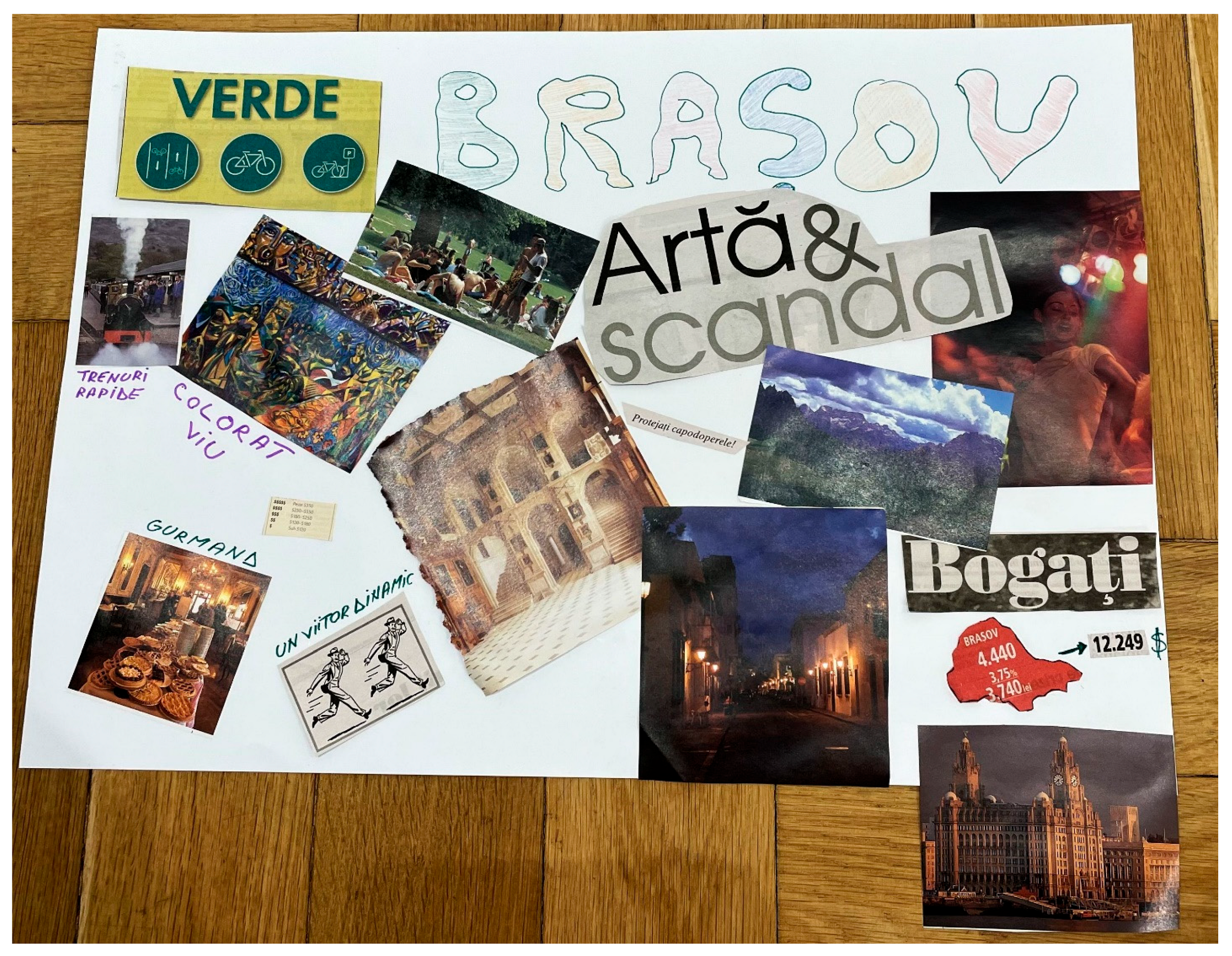

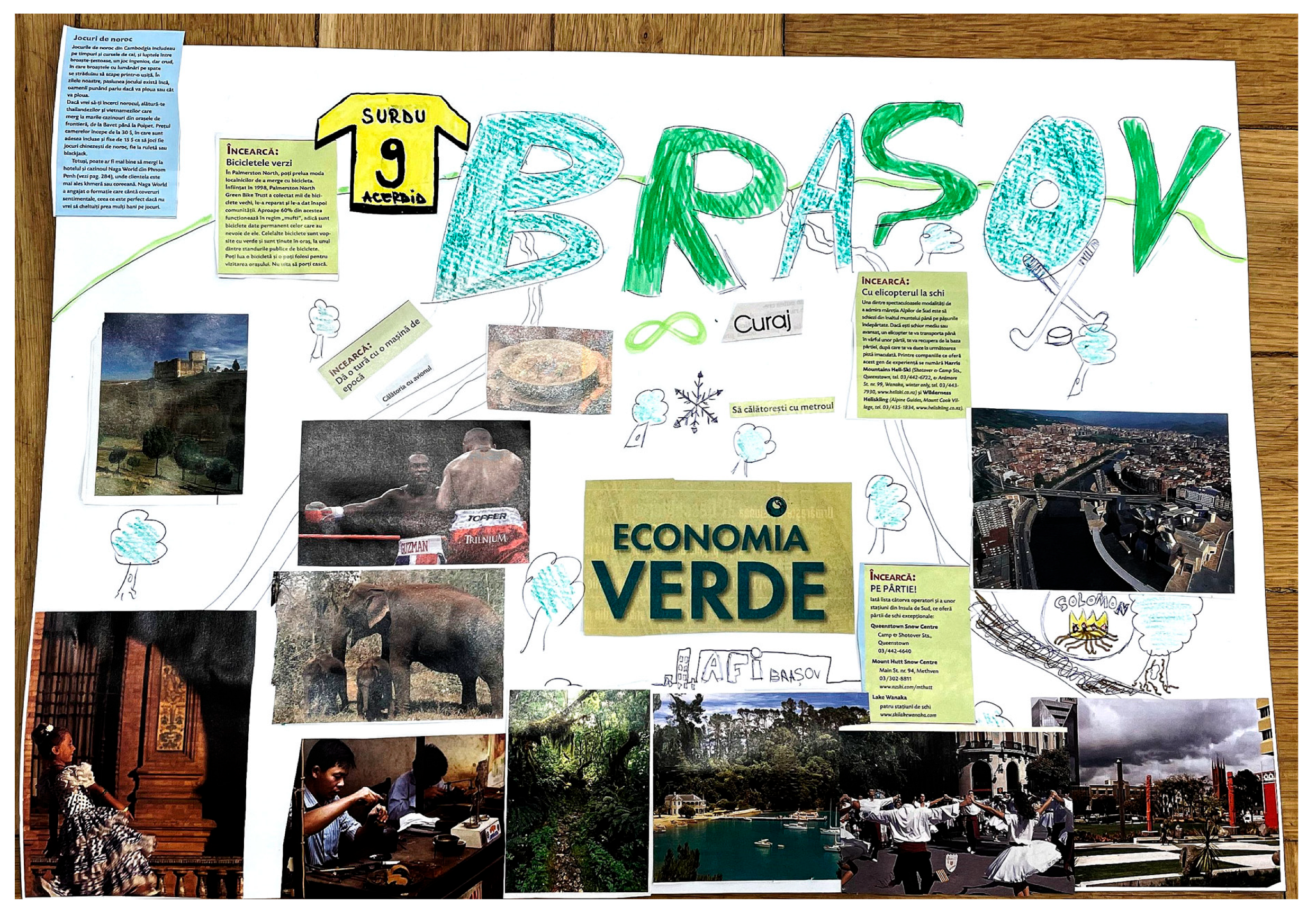

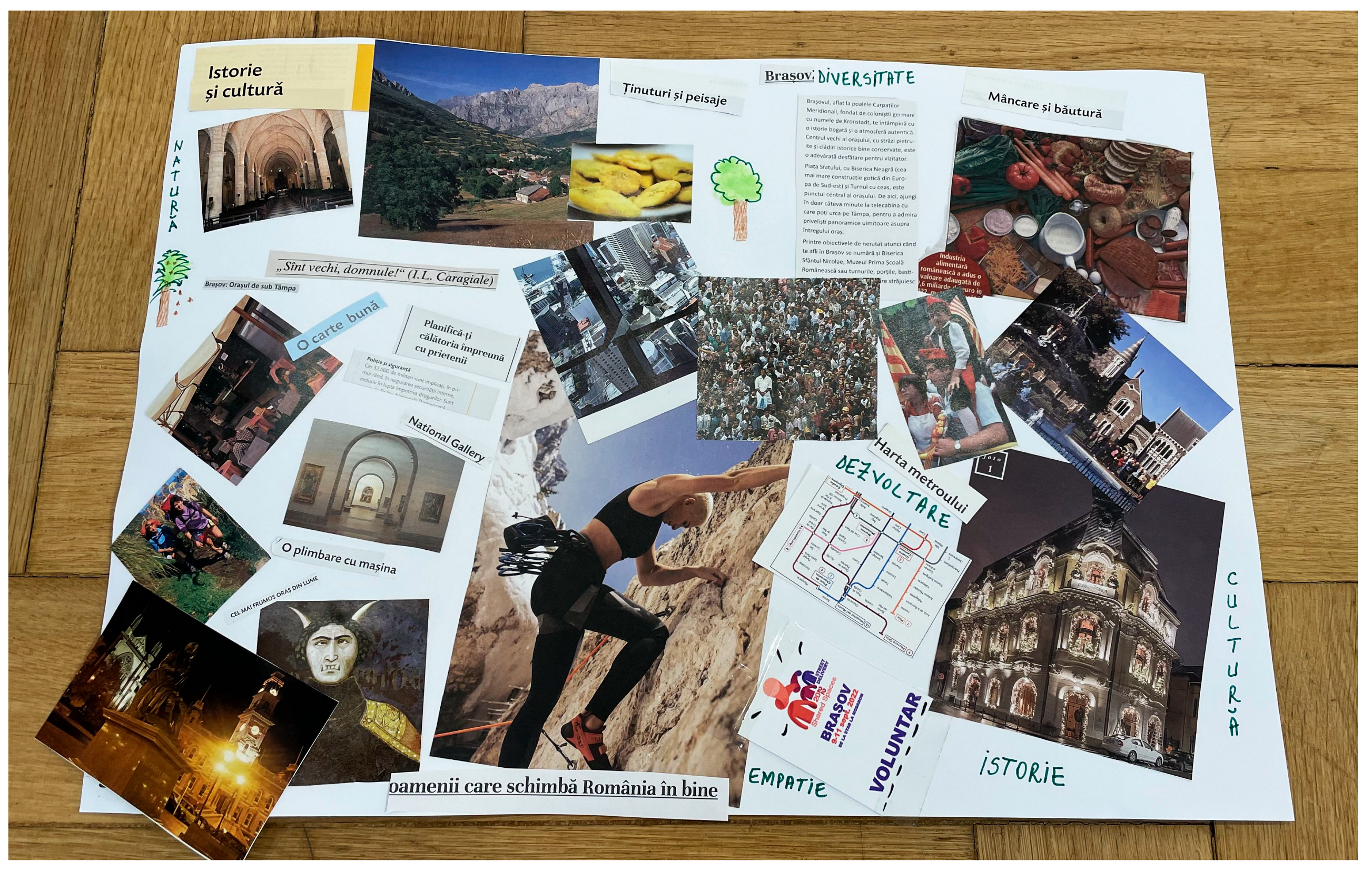

4.1.1. Data Analysis Resulting from the Application of the Second Projective Technique: Thematic Collage “Brașov, My Ideal City”

4.1.2. Individual Study of the Collages Made by the Teams

4.2. Results of the In-Depth Interviews

4.3. Results of the Quantitative Study

5. Discussion

6. Research Limitations and Potential Areas for Further Investigation

6.1. Focus Group Studies

6.2. In-Depth Interviews with Cultural Leaders in Brașov

6.3. Quantitative Study on Gen Z and the Cultural Environment in Brașov

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moilanen, T.; Rainisto, S. How to Brand Nations, Cities and Destinations; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; de Jong, M.; de Bruijne, M.; Schraven, D. Economic City Branding and Stakeholder Involvement in China: Attempt of a Medium-Sized City to Trigger Industrial Transformation. Cities 2020, 105, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Grace, D.; Perkins, H. City Branding Research and Practice: An Integrative Review. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoglu, E. Using Social Media for Participatory City Branding: The Case of @cityofizmir, an Instagram Project. In Global Place Branding Campaigns Across Cities, Regions, and Nations; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, I.S.; Indradjati, P.N. Toward Contemporary City Branding in the Digital Era: Conceptualizing the Acceptability of City Branding on Social Media. Open House Int. 2023, 48, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngangom, M. How TikTok Has Impacted Generation Z’s Buying Behaviour and Their Relationship with Brands? Ph.D. Thesis, Dublin Business School, Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Uzunoglu, E. Using Social Media for Participatory City Branding: The Case of @cityofizmir, an Instagram Project. In Advertising and Branding: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E. Questioning a “One Size Fits All” City Brand. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardhanariswari, K.A.; Probosari, N. Fostering Creativity: Unveiling Kanazawa’s Brand as a Creative City. J. Soc. Political Sci. 2023, 6, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellisanti, R. Cultural and Creative Industries and Regional Development; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Casais, B.; Poço, T. Emotional Branding of a City for Inciting Resident and Visitor Place Attachment. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2023, 19, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, M.B.; Adam, D.R.; Boateng, H.; Kosiba, J.P. Place Attachment and Brand Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Customer Experience in the Restaurant Setting. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2023, 37, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. Arts, Culture and the City: An Overview. Built Environ. 2020, 46, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, B. Deconstructing the City of Culture: The Long-Term Cultural Legacies of Glasgow 1990. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 841–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Henche, B. Urban Experiential Tourism Marketing. J. Tour. Anal. Rev. Anál. Tur. (JTA) 2021, 25, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, S.U. The Role of Culture in City Branding. In Strategic Place Branding Methodologies and Theory for Tourist Attraction; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, C.K.; Chen, H.; Lee, T.J.; Hyun, S.S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y. The Impacts of Under-Tourism and Place Attachment on Residents’ Life Satisfaction. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 30, 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrin, I. European Capital of Culture and Sustainable Tourism: Challenges, Trends and Perspectives. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2024, 72, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosier, S.R.; Badawy, N.M. A Strategy to Create a City Brand as a Tool to Achieve Sustainable Development (Case Study: Branding of Port-Said City-Egypt). In International Work-Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.C.; Pereira, C.R.; Lopes, M.F.; Calisto, R.A.R.; Vale, V.T. Sustainable and Green City Brand. An Exploratory Review. Cuad. Gest. 2023, 23, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero Moreno, L.D. Sustainable City Storytelling: Cultural Heritage as a Resource for a Greener and Fairer Urban Development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, E.E.; Papp-Váry, Á.F.; Kangai, D.; Odunga, S.O. Building a Sustainable Future: Challenges, Opportunities, and Innovative Strategies for Destination Branding in Tourism. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawagvudcharee, O. Engaging Brand Awareness for Sustainable Innovations in Cultural Tourism Towards Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH): The Case Studies of China, Myanmar, Thailand, and Australia. Rev. Gest. Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e010558. [Google Scholar]

- Dinnie, K. City Branding: Theory and Cases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N. De-Centring Tourism’s Intellectual Universe, or Traversing the Dialogue Between Change and Tradition. In The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies: Innovative Research Methods; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, W.; Zhou, L.; Haobin, B.Y.; Yan, Q. Conceptualizing and Assessing the Competitiveness of Slow Tourism Destinations: Evidence from the First Accredited Cittàslow in China. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440211068823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, S.; Ralston, C.; Kenny Rhodes, R.S. Promoting Reykjavík as a Tourist Destination. Bachelor’s Thesis, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Svirčić Gotovac, A.; Kerbler, B. From Post-Socialist to Sustainable: The City of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verances, J.; Rusmiatmoko, D.; Afifudin, M.A. Sustainable Tourism and City Branding: Balancing Growth and Authenticity. J. City Brand. Authent. 2024, 2, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavra, D.P.; Bykova, E.V.; Savitskaya, A.S.; Taranova, Y.V. Communication Strategies of Megacities in the New Digital Reality. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Communication Strategies in Digital Society Workshop, ComSDS 2018, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 11 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, P.O.; Björner, E. Branding Chinese Mega-Cities: Policies, Practices and Positioning; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, I. Geographies of Place Branding: Researching Through Small and Medium Sized Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ciuculescu, E.-L.; Luca, F.-A. How Can Cities Build Their Brand Through Arts and Culture? An Analysis of ECoC Bidbooks from 2020 to 2026. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.; Chambre, D.; Copolovici, D.M.; Bungau, T.; Bungau, C.C.; Copolovici, L. Heritage Building Preservation in the Process of Sustainable Urban Development: The Case of Brasov Medieval City, Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, K. 5 Things HR Professionals Need to Know About Generation, Z. Strateg. HR Rev. 2017, 16, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, A. Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age. Contemp. Sociol. 2024, 53, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Silva, C.; Figueiredo, C.; Vitória, A.; Nogueira, T.; Dinis, M.A.P. Generation Z: Fitting Project Management Soft Skills Competencies—A Mixed-Method Approach. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T. Make Way for the Next Generation but Avoid the “Brain Drain”. AADE Pract. 2019, 7, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rijke, V. The and Article: Collage as Research Method. Qual. Inq. 2024, 30, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler-Kisber, L.; Poldma, T. The Power of Visual Approaches in Qualitative Inquiry: The Use of Collage Making and Concept Mapping in Experiential Research. J. Res. Pract. 2010, 6, M18. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, A. Real Life In The Digital World: Gen Z’s Search for Authenticity. Available online: https://www.ceotodaymagazine.com/2019/11/real-life-in-the-digital-world-gen-zs-search-for-authenticity/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Wolf, A. Gen, Z & Social Media Influencers: The Generation Wanting a Real Experience. Honors Senior Capstone. 2020. Available online: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/51/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- de las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Millan-Celis, E.; Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. Importance of Social Media in the Image Formation of Tourist Destinations Fromthe Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira Pinto, L.; Gwiaździński, E. The City as a Product of Digital Communication Design. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Design Thinking and Practice in Contemporary and Emerging Technologies; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 13323. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Chang, Z. City Branding Identity Strategy of Creating City Cultural Value-Take the Creation of Shanghai City Branding as an Example. Cult. Commun. Social. J. 2020, 1, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernández, B. Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | ID Code | Age | Gender | Specific Fields of Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Subject 1 | 35–45 | M | Book industry, cultural event organization |

| 2 | Subject 2 | 35–45 | F | Educational trainer, event organizer, visual artist |

| 3 | Subject 3 | 35–45 | M | Cultural entrepreneur |

| 4 | Subject 4 | 35–45 | F | Festival organizer |

| 5 | Subject 5 | 35–45 | F | Festival organizer, film industry, editor |

| 6 | Subject 6 | 35–45 | F | Cultural event organizer, communication expert |

| 7 | Subject 7 | 35–45 | F | Artistic event organizer, art curator |

| 8 | Subject 8 | 25–35 | F | Artist, event organizer |

| 9 | Subject 9 | 35–45 | F | Editor, cultural manager, cultural journalist |

| 10 | Subject 10 | 35–45 | F | Organizer of gastronomic events |

| 11 | Subject 11 | 35–45 | M | Event organizer, educational trainer |

| Objective | Questions Asked in the Questionnaire |

|---|---|

| Objective 1: Investigating the opinions of Generation Z youth about Brașov’s current brand and ranking the city’s brand dimensions. | (a) Do you feel attached to the city of Brașov? (b) Which element from the list do you associate most with the city of Brașov? (Options: architecture, natural environment, artistic/cultural event offerings, economic opportunities, mountain sports, people) |

| Objective 2: Studying how Generation Z youth relate to cultural events in Brașov and culture in general. | (c) How often do you attend cultural events in Brașov? (d) What are the main reasons you don’t attend cultural-artistic events in Brașov more often? (e) Do you think there are enough opportunities for young people to participate in cultural events in Brașov? |

| Objective 3: Assessing the extent to which Generation Z youth in Brașov are open to new technologies in art and culture (AI, VR, AR). | (f) Are you involved in creating artistic content (even at an amateur level)? (g) To what extent are you familiar with the following concepts? (Options: NFT, new media art, AI—Artificial Intelligence, VR—Virtual Reality, AR—Augmented Reality). |

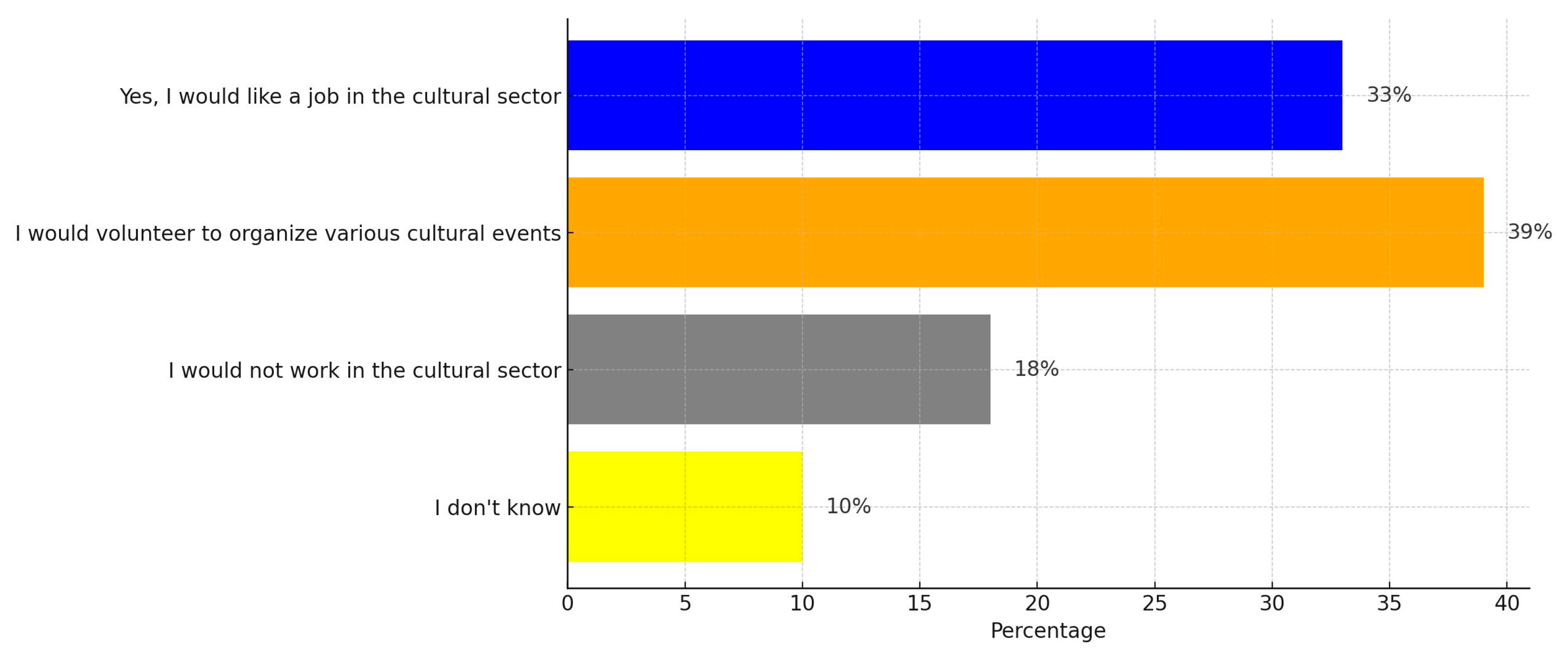

| Objective 4: Determining the extent to which the target audience youth are willing to engage in the cultural field in the future. | (h) Would you be interested in getting involved in the cultural sector in the future? |

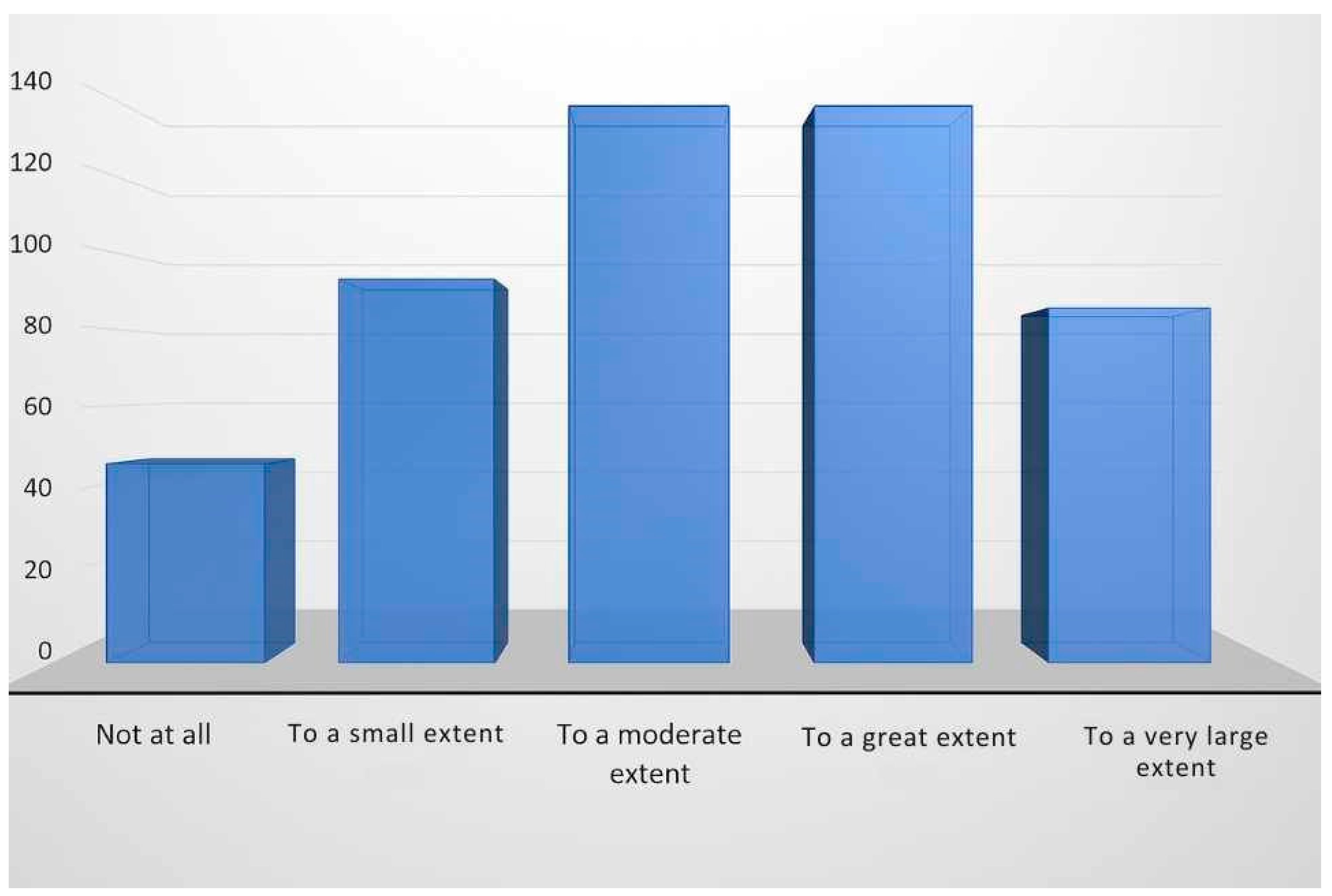

| Objective 5: Understanding Generation Z youth’s opinion about the influence of education on participating in cultural events. | (i) To what extent do you feel your high school/college/master’s education promotes participation in artistic/cultural events? (Scale: 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “to a very large extent”). |

| Respondent | Response |

|---|---|

| Subject 1 | “Brașov is 35–40 years old but continues to grow younger, like in the movie Benjamin Button. With each passing year, it develops more and more, becomes environmentally friendly, and allows easy and safe travel anywhere. Compared to other cities, Brașov is green.” |

| Subject 2 | “Brașov is a young person between 25 and 35 years old, calm, peaceful, friendly, yet fun and full of life. It loves traveling, attending parties, taking nature walks, and is the soul of the group.” |

| Subject 3 | “An older person, around 70 years old, considering the old town center and historical buildings, like the Black Church, which has a rich history. These give me the feeling of an older person. They spend the day outdoors hiking, walking in parks, climbing mountains (like Tampa or the Snail Hill), visiting museums, bookstores, and reading during their free time.” |

| Subject 4 | “My Brașov is 30–40 years old, a calm person but occasionally bursts out (I thought of the traffic). It’s a tall person because we are surrounded by mountains. They care about the future and the well-being of others, have a large family, and take care of it. They love nature, are open-minded, eager to evolve, intelligent, and know what they want but need guidance to achieve it.” |

| Subject 5 | “A young, active person under 30 who loves traveling, exploring the mountains (Postăvaru, Tampa), and skiing. They enjoy photography, discovering new perspectives of places, and are a foodie because the city offers traditional and delicious cuisine.” |

| Subject 6 | “A man, around 30–40 years old, charismatic, gentle, patient, and enthusiastic. I imagine them in a suit, taking nature walks and photographing landscapes during their free time.” |

| Subject 7 | “Brașov would be an older person, over 70 years old, full of historical stories. A gentle person eager to help, whether it’s solving a historical or cultural question. They help you find friends. Their main activities include outdoor hikes, park walks, skiing, and visiting museums.” |

| Subject 8 | “A young, active person under 30 who loves traveling, hiking, exploring Tampa and Postăvaru, skiing, and capturing the most beautiful places and architectural angles through photography.” |

| Subject 9 | “A calm personality oriented toward a healthy lifestyle. About 45 years old, with hobbies like hiking, climbing, and skiing.” |

| Subject 10 | “Calm, clean, green-haired. I imagine them around 60 years old.” |

| Subject 11 | “A person under 50, neither old nor young, averaging the city’s history and lifestyle. A person who always dresses warmly.” |

| Subject 12 | “My Brașov would be 35–40 years old, a family-oriented individual who enjoys outdoor walks.” |

| Subject 13 | “I thought of a younger, active, clean person, full of energy and many ideas.” |

| Subject 14 | “If Brașov were a person, it would be 30 years old and take many nature walks.” |

| Subject 15 | “A person around 35–40 years old, seeking peace and nature walks, engaging in recreational activities.” |

| Subject 16 | “A 35-year-old person, strong and calm, practicing sports and various winter activities.” |

| Subject 17 | “A 30-year-old man, wise, quiet, reflective, creative. His passions include reading, hiking, and cinema.” |

| Subject 18 | “A person aged 35–40 who desires to create beautiful things. They enjoy hiking and running in nature, have a strong character, a balanced lifestyle, and can achieve anything they set their mind to.” |

| Subject 19 | “To me, Brașov would be 30 years old because, although it is a historical city, it continues to develop and feels younger with each passing year. Throughout the day, it goes hiking, strives for continuous development, and leads a healthy lifestyle. It’s an empathetic person, eager to evolve, and a bit of a psychologist for the nation since people come here to relax and recharge.” |

| Subject 20 | “To me, the city is a 65-year-old lady. I see her as a grandmother waiting for you at home, offering you the best she has. She is warm and sociable, telling stories about history and the old days, like how Brașov’s center used to be. On a typical day, she watches the sunrise, cooks for her grandchildren, then goes downtown for tea and a stroll under Tampa to admire nature.” |

| Subject 21 | “A 70-year-old gentleman who hikes on Tampa and reads. This reflects the city’s historical air and atmosphere.” |

| Subject 22 | “Brașov is a 30-year-old man, stable, physically active, passionate about history, a bright-faced person who enjoys helping others, reads and studies extensively, and is culturally developed.” |

| Respondent | Hobbies/Leisure Activities: Cultural Aspects |

|---|---|

| Respondent 3 | “...visits museums, bookstores, reads in their free time.” |

| Respondent 4 | “...an open person who wants to grow and evolve.” |

| Respondent 5 | “...enjoys photography, finding new perspectives on places. A gourmand.” |

| Respondent 6 | “...photographs landscapes.” |

| Respondent 7 | “...visits museums.” |

| Respondent 8 | “...takes photographs.” |

| Respondent 17 | “...hobbies include reading and cinematography.” |

| Respondent 19 | “...would like to develop continuously.” |

| Respondent 20 | “...tells stories about history and the past, like what Brașov’s center used to be like.” |

| Respondent 21 | “...reads.” |

| Respondent 22 | “...passionate about history, reads and studies extensively.” Also described as “...a person very culturally developed.” |

| Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| More than once a month | 162 | 27.0 | 27.0 |

| Once every two–three months | 159 | 26.5 | 53.5 |

| Less than once every two–three months | 222 | 37.0 | 90.5 |

| I don’t attend cultural events | 57 | 9.5 | 100.0 |

| Total | 600 | 100.0 |

| Number of Responses | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| I do not receive information about cultural events in the city | 138 | 23.0 |

| I am more of a consumer of other types of events/activities (e.g., sports, video games) | 60 | 10.0 |

| My schedule is already very busy | 195 | 32.5 |

| I am influenced by the fact that my friends usually do not attend such events | 108 | 18.0 |

| I would like to attend events, but the tickets are too expensive | 54 | 9.0 |

| I would like to participate in cultural/artistic activities, but I do not feel that the events in the city are for me | 42 | 7.0 |

| Others | 3 | 0.5 |

| Total | 600 | 100.0 |

| Hypothesis | Validated/Invalidated |

|---|---|

| The majority of respondents associate Brașov with tourism and the natural environment. | Validated |

| The majority of interviewed students do not associate Brașov’s city brand with cultural events. | Validated |

| Most respondents are not familiar with the city’s cultural offerings. | Partially validated |

| The target audience believes that the local cultural offer is insufficient. | Validated |

| The majority of young people think that cultural events in Brașov are insufficiently promoted. | Validated |

| Hypothesis | Validated/Invalidated |

|---|---|

| The majority of cultural operators believe that Brașov’s cultural brand is currently represented by the natural environment, the Old Town, and mountain activities. | Validated |

| A large portion of respondents consider the local cultural infrastructure to be insufficient. | Validated |

| The main issue faced by cultural operators in Brașov is the lack of consistent and predictable funding. | Validated |

| Some event organizers do not believe that Brașov has a cultural brand. | Validated |

| Hypothesis | Validated/Invalidated |

|---|---|

| The attachment level of Generation Z to the city of Brașov is moderate. | Invalidated |

| The majority of the target audience associates the city of Brașov with its architecture and natural environment. | Validated |

| Over 50% of subjects attend cultural events in Brașov at least once every two to three months. | Validated |

| Over two-thirds of Generation Z youth do not attend cultural events in Brașov more often, mainly due to lack of information. | Validated |

| Over 70% of Generation Z youth believe that the cultural-artistic environment is important for their education and development. | Validated |

| Over 50% of young people believe there are not enough cultural opportunities in Brașov. | Invalidated |

| At least 50% of Generation Z youth produce cultural content at least at an amateur level. | Validated |

| Modern concepts in art (NFT, New Media Art, AI, VR, AR) are known, on average, to a large extent by Generation Z youth in Brașov. | Invalidated |

| Less than 50% of Generation Z youth in Brașov are interested in becoming involved in the cultural field in the future. | Invalidated |

| Over 50% of the responding youth believe that their education contributes to their participation in cultural events. | Validated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciuculescu, L.; Luca, F.A. Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083361

Ciuculescu L, Luca FA. Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083361

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiuculescu, Lavinia, and Florin Alexandru Luca. 2025. "Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083361

APA StyleCiuculescu, L., & Luca, F. A. (2025). Developing a Sustainable Cultural Brand for Tourist Cities: Insights from Cultural Managers and the Gen Z Community in Brașov, Romania. Sustainability, 17(8), 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083361