Abstract

The global popularity of South Korean dramas (K-dramas), central to the “Korean Wave”, has significantly influenced international perceptions of Korea and its tourism appeal. This study examines the impact of K-drama consumption on American audiences’ intentions to visit South Korea, with a focus on the sustainability messaging embedded within the media. Integrating the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and uses and gratifications theory (UGT), this research explores how cultural perceptions and the engagement with Korean culture shape sustainable tourism attitudes and travel intentions. A survey of 554 U.S.-based participants reveals that positive cultural perceptions foster engagement, which mediates the relationship with sustainable attitudes and intentions to visit Korea. Furthermore, sustainability messaging in K-dramas enhances the connection between cultural engagement and eco-conscious travel behaviors. The findings highlight the influential role of the media in shaping sustainable tourism and offer strategic insights for leveraging K-dramas in tourism marketing. While K-dramas may not fulfill a direct diplomatic function, they contribute to Korea’s soft power by enhancing cultural exposure.

1. Introduction

The global influence of South Korean media content, particularly Korean dramas (K-dramas), has reached unprecedented levels, captivating audiences across the world [1]. This phenomenon, often referred to as the “Korean Wave” or “Hallyu”, has not only reshaped perceptions of South Korea but has also elevated its status as a cultural and tourism powerhouse [2,3]. Beyond their entertainment value, K-dramas serve as dynamic conduits for cultural diplomacy, offering immersive portrayals of Korean traditions, lifestyles, and landmarks that resonate deeply with international audiences [4,5,6].

In recent years, K-dramas have demonstrated a profound impact on tourism, effectively bridging the gap between cultural fascination and travel motivation [1,5]. Iconic series, such as Squid Game on Netflix, have transcended linguistic and geographical barriers, showcasing Korea’s societal narratives while subtly introducing its cultural and physical landscapes [2,6]. The proliferation of over-the-top (OTT) platforms, like Netflix, has been instrumental in this regard, amplifying the accessibility and visibility of K-dramas on a global scale [2,3,4,6]. These platforms provide localized subtitles and dubbing, which not only enhance viewer engagement but also foster cultural curiosity and cross-cultural exchange, thus accelerating the influence of Korean media on international tourism [1,7,8].

American tourists represent a steadily growing and strategically important segment for South Korea’s inbound tourism market. According to the Korea Tourism Data Lab (KTDL), the number of American visitors to South Korea has shown a strong upward trend, surpassing 1.0 million in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic and rebounding to over 1.3 million in 2024 [9]. The U.S. consistently ranks among the top five source markets for inbound tourism to Korea [9]. This steady interest underscores the importance of understanding how cultural exports like K-dramas influence American travelers’ perceptions and intentions, particularly with the growing emphasis on sustainable tourism development.

Despite the growing recognition of K-dramas as catalysts for tourism, the prior research in this domain remains constrained by several critical limitations. First, much of the existing literature centers on the economic and cultural implications of the Korean Wave, often neglecting the psychological processes underpinning travel intentions [1]. Second, there has been limited exploration of how the sustainability themes embedded in media narratives influence tourism behavior [4,5,8,10]. Although many studies have focused on general perceptions and motivations, they have overlooked the nuanced role of the media in shaping responsible tourism practices [1,5,8]. While some scholars suggest that the consumption of cultural media, such as K-dramas, positively influences international tourists’ perceptions and travel intentions [1,11], others caution against overgeneralization. Hudson and Ritchie (2006), for example, argue that media exposure may increase awareness but does not necessarily lead to actual travel behavior [12]. Similarly, Kim and Richardson (2003) found that although film tourism enhances the destination image, it may not significantly affect behavioral intentions [13]. These mixed findings underscore the need for further empirical investigation, especially in the context of American audiences and sustainability-focused narratives. Finally, there is a notable lack of research examining the American audience, a demographic that not only constitutes a significant viewership for K-dramas but also represents a vital market for South Korea’s tourism sector.

This study seeks to fill these gaps by investigating the relationship between K-drama consumption and American consumers’ intentions to visit South Korea, with a particular emphasis on sustainability [1,7]. Drawing on established theoretical frameworks, such as the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and uses and gratifications theory (UGT), this research delves into the psychological mechanisms that mediate the influence of K-dramas on travel intentions [8,14]. Furthermore, it examines the moderating role of sustainability messaging within K-drama content [4], offering insights into whether such narratives inspire eco-conscious and culturally sensitive travel behaviors.

The contributions of this study are multifaceted. Theoretically, it advances the discourse on media-driven tourism by integrating sustainability considerations, thereby addressing an overlooked intersection between entertainment media and responsible tourism. It also enriches the understanding of the cross-cultural media influence by focusing on the American audience, providing a nuanced analysis of their engagement with K-dramas and its implications for travel behavior. Practically, this research offers actionable insights for tourism stakeholders, including marketers, policymakers, and content creators, enabling them to strategically leverage K-dramas as tools for promoting sustainable tourism. By foregrounding the interplay between media consumption and sustainability, this study underscores the potential of K-dramas to influence global audiences’ perceptions and promote South Korea as a culturally engaging and sustainable travel destination.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

This study is grounded in two prominent theoretical frameworks: the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the uses and gratifications theory (UGT). These frameworks provide a robust foundation for understanding the mechanisms through which media consumption influences travel intentions.

The TPB, proposed by Ajzen [15], is one of the most widely applied models for predicting human behavior in various contexts, including tourism [16]. It posits that behavioral intentions are determined by three core components: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [17]. Attitudes reflect an individual’s evaluation of a particular behavior as favorable or unfavorable [15]. Subjective norms capture the influence of social pressures, reflecting the perceived expectations of others regarding the behavior [16,18]. Perceived behavioral control relates to the individual’s perception of their ability to perform the behavior, considering both internal and external constraints [17]. In the context of this study, the TPB provides a structured framework to explore how K-drama exposure influences travel intentions by shaping positive attitudes toward visiting Korea, reinforcing subjective norms through social discourse, and enhancing perceived behavioral control through the accessibility of travel information embedded in the media content [2,10,14,16].

The UGT focuses on the audience’s active role in selecting media to satisfy specific psychological and social needs [19,20]. Unlike traditional media effects theories, the UGT highlights that individuals seek out content to fulfill cognitive, affective, personal integrative, social integrative, and escapism needs [21,22]. Cognitive needs involve seeking knowledge and information, while affective needs relate to emotional experiences [23]. Personal integration needs pertain to reinforcing one’s confidence or credibility, whereas social integrative needs focus on fostering connections with others [22]. Escapism needs to address the desire for a diversion from reality [19]. In this study, the UGT provides valuable insights into why audiences engage with K-dramas, emphasizing how these dramas fulfill cognitive needs through cultural exploration, affective needs via compelling narratives, and socially integrative needs through community [21,23]. This engagement not only deepens cultural immersion but also cultivates travel motivations [19,20,22].

The integration of the TPB and UGT in this research is both novel and theoretically justified. While the TPB offers a predictive model of behavioral intentions [15,16], it does not explicitly address the motivations underlying media consumption. The UGT complements the TPB by explaining the psychological gratifications derived from K-drama engagement, which, in turn, influence the components of the TPB—attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [20,22]. For instance, K-dramas often portray Korea’s scenic landscapes, cultural festivals, and traditional practices, satisfying viewers’ cognitive and affective needs [2,4]. This shapes favorable attitudes toward visiting Korea and reinforces subjective norms through shared cultural appreciation within fan communities [5]. Furthermore, K-dramas provide practical information on destinations, food, and cultural etiquette, enhancing the perceived behavioral control by reducing uncertainty about travel [1,10].

By applying these frameworks in tandem, this study develops a comprehensive model that bridges the gap between media engagement and travel behavior. The integration of the TPB and UGT enables a deeper understanding of how K-drama consumption influences the psychological mechanisms driving sustainable tourism intentions [8,14]. This approach not only addresses gaps in the existing literature but also highlights the transformative potential of media content in shaping consumer behavior in the context of international tourism [21].

2.2. Hallyu and Media-Driven Destination Perception

K-dramas, as a central component of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), have significantly influenced how international audiences perceive South Korea by showcasing cultural values, modern lifestyles, and appealing destinations. Through highly stylized depictions of Korean cities, cuisine, fashion, and interpersonal relationships, K-dramas serve as both entertainment and indirect destination marketing tools [24,25]. The narratives and visuals presented in these dramas can stimulate affective and cognitive responses that shape viewers’ attitudes toward Korea as a desirable travel destination [1,10].

The influence of Hallyu extends beyond K-dramas, encompassing K-pop, beauty products, cuisine, and fashion, all of which contribute to constructing a multifaceted image of Korea. This holistic exposure increases the curiosity and emotional connection toward Korean culture and motivates travel behavior [26,27]. Research has shown that exposure to multiple facets of Korean pop culture enhances the national brand image and creates a sense of familiarity that lowers perceived barriers to travel [28,29]. In this way, Hallyu serves as a powerful instrument of soft power and cultural diplomacy [30,31].

The para-social interaction with K-drama characters also plays a key role in shaping travel intentions, as audiences form perceived relationships with characters and aspire to experience the environments in which the stories unfold [32,33]. These emotional bonds often translate into destination loyalty and concrete travel planning [34,35]. As a result, the Hallyu phenomenon not only increases the visibility of Korean destinations but also elevates their symbolic and affective value in the eyes of global viewers, making Hallyu a critical driver of tourism behavior [11,36].

2.3. Constructs and Hypotheses Development

2.3.1. Cultural Perception of Korea

Cultural perception refers to the extent to which individuals positively evaluate Korea’s cultural, historical, and societal attributes [37,38,39]. This construct encapsulates how audiences interpret and internalize the cultural representations they encounter, particularly through media [40]. K-dramas serve as cultural ambassadors by presenting Korea as a compelling blend of tradition and modernity, showcasing local cuisines, festivals, and architectural landmarks. According to the TPB, these favorable perceptions form the basis for developing positive attitudes toward visiting Korea [39]. From a UGT perspective, cultural perception satisfies cognitive needs for knowledge and understanding of a foreign culture, fostering curiosity and admiration [37,40]. As individuals gain a more favorable view of Korea’s cultural richness, they are more likely to actively engage with its culture [38,39]. Thus, the researchers establish the following research hypothesis:

H1:

The positive cultural perception of Korea is positively associated with engagement with Korean culture.

2.3.2. Engagement with Korean Culture

Engagement with Korean culture refers to the degree to which individuals actively immerse themselves in activities that reflect an interest in Korea’s traditions, practices, and modern lifestyle [41]. This construct is central to the mediation process that links cultural perception to behavioral intentions [42]. Through the lens of the TPB, engagement reflects how attitudes derived from positive cultural perceptions are translated into exploratory actions, such as learning the Korean language, trying traditional foods, or researching travel options [41,43]. The UGT further explains that K-drama audiences engage with Korean culture because such activities fulfill affective needs (emotional connection to the narrative or characters) and personal integrative needs (enhancing self-identity through cultural exploration) [42]. For example, individuals who admire the intricate Hanbok costumes in K-dramas may be motivated to visit cultural heritage sites to experience them firsthand [41,43]. Accordingly, this study proposes the following research hypothesis:

H2:

Engagement with Korean culture is positively associated with an intention to visit Korea.

2.3.3. Sustainable Tourism Attitudes

Sustainable tourism attitudes describe an individual’s predisposition to engage in environmentally friendly, culturally respectful, and socially responsible travel practices [44]. These attitudes represent a vital extension of the TPB, aligning with the ethical dimensions of behavioral beliefs [45]. K-dramas often incorporate subtle sustainability narratives, such as preserving natural landscapes or respecting traditional communities, which influence viewers to align their travel plans with eco-conscious values [4,46]. The UGT adds that sustainability themes embedded in media fulfill personal integrative needs, reinforcing self-concepts tied to responsible global citizenship [44,45]. For instance, scenes showcasing serene Korean mountains or traditional markets can inspire viewers to prioritize visiting less commercialized and more environmentally sensitive destinations [46,47]. Hence, the researchers suggest the following research hypothesis:

H3:

Engagement with Korean culture is positively associated with sustainable tourism attitudes.

Cultural perception reflects individuals’ cognitive and affective evaluations of a destination’s cultural, historical, and societal attributes [48]. K-dramas act as powerful cultural mediators, showcasing Korea’s traditions, festivals, and natural landscapes, which foster admiration and emotional connections among viewers [1]. According to the TPB, such favorable perceptions form the basis of attitudes that prioritize eco-friendly [18], culturally respectful, and socially responsible travel [1]. The UGT further explains how K-dramas fulfill viewers’ cognitive needs for cultural knowledge and appreciation [19,22]. An exposure to narratives emphasizing cultural preservation and sustainability cultivates viewers’ values and predispositions toward sustainable tourism [48]. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that cultural perception plays a critical role in shaping sustainable tourism attitudes.

H4:

A positive cultural perception of Korea is positively associated with sustainable tourism attitudes.

2.3.4. Intention to Visit Korea

The intention to visit Korea reflects the likelihood that an individual will plan a trip to the country, serving as the ultimate dependent variable in this study [15]. The TPB suggests that intentions are shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, all of which are influenced by prior media exposure [17]. K-drama consumption creates emotionally resonant and cognitively enriching experiences, satisfying the UGT’s premise that media gratifications translate into behavioral outcomes [1,20,37]. For instance, individuals inspired by the romantic depiction of Korean historical sites may form strong intentions to visit these locations, especially when sustainability messaging reinforces the desirability of preserving such destinations for future generations [20]. Thus, the researchers establish the following research hypothesis:

H5:

Sustainable tourism attitudes are positively associated with intentions to visit Korea.

2.3.5. Sustainability Messaging in K-Dramas

Sustainability messaging in K-dramas refers to explicit or implicit depictions of eco-conscious behaviors, cultural preservation, and sustainable lifestyles [49]. According to the TPB, sustainability messaging can influence subjective norms by portraying these behaviors as socially desirable and aligned with the expectations of others [15]. The UGT complements this by suggesting that sustainability-focused narratives satisfy cognitive and affective needs, increasing viewers’ awareness and emotional investment in sustainable practices [21]. For example, a K-drama that features a storyline about preserving traditional tea-growing practices may evoke both an intellectual appreciation for cultural heritage and an emotional connection to the characters involved, leading to a stronger alignment with sustainability values [1]. The effectiveness of such messaging is moderated by the viewer’s engagement level, with those highly immersed in Korean culture being more responsive to sustainability cues [49]. Consequently, the researchers propose the following research hypothesis:

H6:

The sustainability messaging in K-dramas moderates the relationship between engagement with Korean culture and sustainable tourism attitudes, such that the relationship is stronger when the sustainability messaging is prominent.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

This study targeted U.S.-based participants who met the following criteria: (1) they had watched at least one Korean drama via an over-the-top (OTT) streaming platform and (2) they had actively engaged with Korean culture, such as considering travel or exploring Korean traditions. A professional marketing research firm was engaged to recruit participants using their existing database of consumers with interests in global media and travel. This ensured the inclusion of individuals familiar with the study context and capable of providing relevant insights.

To confirm eligibility, participants were required to answer two screening questions: (1) “Have you watched any Korean drama on an OTT platform? If yes, please provide the title” and (2) “Have you recently engaged in activities related to Korean culture, such as learning the language, trying the cuisine, or researching travel to Korea?” Responses were verified to ensure that only those meeting both criteria were included. Participants providing incomplete or inconsistent answers were excluded from the study.

Data collection was conducted over a two-week period, using an online survey distributed by the research firm. The survey was designed to capture insights into participants’ media engagement, cultural perceptions, and travel intentions. Rigorous quality checks were implemented to ensure data validity, including cross-verification of screening responses and analysis of completion patterns. A total of 600 participants began the survey, but after excluding incomplete or invalid responses 554 valid cases remained for analysis (see Table 1). This process ensured a high-quality dataset, providing a robust basis for exploring the relationships between K-drama engagement, cultural curiosity, and tourism intentions.

Table 1.

Demographic analysis of respondents.

To assess the representativeness of the sample in relation to U.S. travelers visiting Korea, the researchers compared the demographic characteristics of the participants with publicly available data from the Korea Tourism Organization’s Korea Tourism Data Lab [9]. According to the 2023 statistics, the gender distribution of U.S. visitors to Korea was 49.9% male and 50.1% female, whereas the sample of this study was 51.3% male and 48.7% female. This indicates that the gender distribution in the study sample is generally comparable to that of actual U.S. travelers to Korea. However, it should be noted that this study specifically targeted individuals who have an interest in Korean culture or have considered traveling to Korea, rather than those who have already visited. Therefore, while the sample shares certain demographic characteristics with U.S. travelers to Korea, its composition reflects a broader group of individuals engaged with Korean culture beyond just actual visitors.

3.2. Measures

The measures used in this study were carefully selected and adapted from established scales in the literature to ensure reliability and validity. Each construct was operationalized using multi-item scales, and the questionnaire was pretested to refine clarity and relevance. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree), unless otherwise specified.

To measure participants’ perceptions of Korea’s cultural, historical, and societal attributes, items were adapted from prior research on destination image and cultural perception [50]. These items captured cognitive and affective evaluations, reflecting the TPB’s conceptualization of attitude formation. Sample items included the following: “Korean culture is rich and fascinating”, “Korean traditions are unique and appealing”, and “I perceive Korea as a culturally engaging destination”. These measures provided a comprehensive assessment of how participants evaluate Korea’s cultural appeal through media exposure.

Engagement with Korean culture was assessed using scales adapted from media engagement and cultural immersion studies [51]. This construct focused on participants’ active involvement in Korean culture through activities inspired by media exposure. Sample items included the following: “I actively seek out Korean cultural experiences”, “Watching Korean dramas motivates me to learn more about Korean culture”, and “I feel emotionally connected to Korean culture through media”. Additionally, frequency-based questions were used to capture specific behaviors, such as trying Korean cuisine or learning the Korean language, ensuring a holistic understanding of cultural engagement.

Items measuring sustainable tourism attitudes were adapted from Choi and Sirakaya’s and other tourism behavior studies [52,53]. These items assessed participants’ predispositions toward eco-friendly, culturally respectful, and socially responsible travel behaviors. Sample items included the following: “I prefer travel experiences that preserve the local environment”, “It is important for me to respect local traditions and cultures when traveling”, and “I am willing to support community-based tourism initiatives”. These measures aligned with the TPB’s focus on behavioral beliefs and contributed to this study’s emphasis on sustainability in tourism.

To assess the perceived prominence of sustainability themes in K-dramas, items were developed based on content analysis frameworks from media influence studies [2]. Participants rated their agreement with statements such as the following: “The K-dramas I watch highlight the importance of preserving natural environments”, “K-dramas promote sustainable and responsible behaviors”, and “I have noticed messages about eco-friendly practices in the K-dramas I watch”. These items captured both explicit and implicit sustainability messages embedded in K-drama narratives and visuals.

Intention to visit Korea was measured using scales from tourism and behavioral intention studies [15]. This construct reflected participants’ likelihood of planning and undertaking a trip to South Korea. Sample items included the following: “I intend to visit Korea in the next 1–3 years”, “I am motivated to visit Korea after consuming its media content”, and “I am planning a trip to Korea to explore its cultural and natural landmarks”. These items aligned with the TPB’s focus on behavioral intentions as predictors of actual behavior and served as the dependent variable in the study.

The questionnaire was developed in several stages to ensure rigor and clarity. All measures were adapted from validated scales in prior literature, ensuring construct validity. The initial questionnaire was reviewed by three experts in tourism and media studies to refine item phrasing and alignment with the research objectives. Following the expert review, a pilot study was conducted with 30 participants who met the study’s inclusion criteria. Feedback from the pilot study was used to identify ambiguities and improve the clarity and flow of the questionnaire. Based on the pretesting results, minor modifications were made to the wording of some items, and the questionnaire was finalized for distribution. This multi-step process ensured that the measures were contextually appropriate and psychometrically robust, providing a solid foundation for subsequent data analysis.

3.3. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and IBM AMOS 26. Frequency analysis and reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha) were performed using SPSS to assess sample characteristics and internal consistency of the constructs, respectively. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis, including confirmatory factor analysis and structural path modeling, was performed using AMOS. Specifically, this study followed Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) two-step approach to SEM [54]. First, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the measurement model and assess construct reliability and validity. After confirming satisfactory model fit and psychometric properties, the structural model was tested to examine the hypothesized paths among the latent constructs. The two-step approach enhances the rigor and reliability of empirical research by ensuring accurate construct measurement before testing structural relationships. This method improves theoretical and statistical clarity, minimizes biases, and results in clearer, more valid findings. By validating the measurement model first, researchers built a solid foundation for robust and credible structural analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

To mitigate the common method bias (CMB), this study adopted several procedural strategies as suggested by Podsakoff et al. [55]. Specifically, participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential. Additionally, different cover stories were utilized for each survey instrument to help respondents psychologically distinguish between the measures. Despite this preventive survey design, the potential for a CMB cannot be entirely ruled out due to the cross-sectional research design, which involved self-reported assessments of both the independent variables, the mediators, and the dependent variable.

To statistically assess the presence of a CMB, the researchers employed two techniques. Firstly, the researchers conducted Harman’s one-factor analysis, and the results revealed that the largest single factor explained less than 50% of the total variance. Second, an unmeasured marker variable was employed [55,56], and the analysis revealed that the marker variable accounted for an average of 2.66% (–0.097 ≤ λ ≤ 0.293) of the total variance in the indicators, whereas the relevant constructs explained an average of 62.7% (0.579 ≤ λ ≤ 0.940). Based on these findings, it was determined that the CMB did not significantly distort the variance in this study.

4.2. Measurement Model

This study adopted a two-step approach to evaluate the measurement model’s reliability and validity, as outlined in Table 2 and Table 3 [54]. Reliability was first assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and the composite construct reliability (CCR) [57]. All the constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 for both measures, indicating a high internal consistency. For instance, the cultural perception achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.830 and a CCR of 0.800, confirming the reliability of the scales (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measurement model from confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 3.

Construct intercorrelations (Φ), mean, and standard deviation (SD).

Second, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results provided evidence of a good model fit, with indices such as χ2 = 525.784, df = 142, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.071, Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.928, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.946, and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.946, all meeting or exceeding recommended thresholds. These results confirm the adequacy of the measurement model and its compatibility with the subsequent structural analysis. The CFA also confirmed strong factor loadings for all constructs, with values ranging from 0.579 to 0.940 (all significant at p < 0.001), indicating that the observed variables accurately represented their respective latent constructs [58].

The convergent validity was established by examining the average variance extracted (AVE) values, all of which surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.50, as shown in Table 3 [59]. For example, the AVE for engagement with Korean culture was 0.615, indicating that the indicators sufficiently captured the construct. The discriminant validity was assessed through construct intercorrelations, where the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its correlations with other constructs, providing additional support for the construct validity [59].

4.3. Evaluation of Structural Model

This study employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate the relationships among constructs and test the proposed hypotheses [58]. SEM was particularly advantageous for its ability to assess complex relationships among latent variables while accounting for measurement error, providing a robust framework for simultaneously evaluating direct, indirect, and moderating effects. Additionally, a multi-group analysis was conducted to explore the moderating role of sustainability messaging in K-dramas (H6), using a standardized deviation split approach to differentiate between low and high groups based on their perception of sustainability messaging.

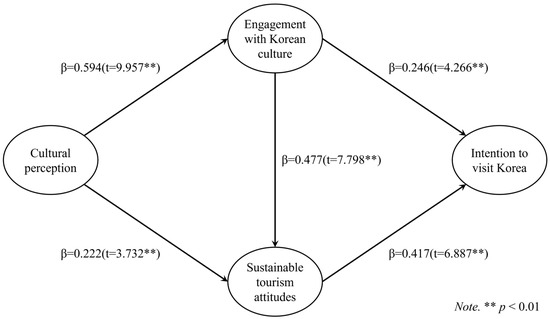

The fit indices for the SEM model were as follows: Chi-square (χ2) = 356.275 (df = 85, p < 0.001), RMSEA = 0.077, NFI = 0.925, CFI = 0.942, and IFI = 0.942. These indices indicate a good overall model fit, with a RMSEA below 0.08 suggesting a reasonable error of approximation and the CFI, IFI, and NFI values above 0.90 reflecting a well-fitting model [58] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Estimates of structural model with whole samples.

H1: Cultural perception → engagement with Korean culture: The SEM results confirmed a strong positive relationship between cultural perception and engagement with Korean culture (standardized estimate = 0.594, critical ratio = 9.957, p < 0.01), as shown in Table 4. This indicates that individuals with favorable perceptions of Korean culture, shaped significantly by media exposure, are more likely to actively participate in Korean cultural activities, such as exploring Korean cuisine, traditions, and lifestyles. The integration of the UGT and TPB frameworks explains this phenomenon: cultural perception satisfies viewers’ cognitive and affective needs, encouraging a deeper cultural immersion. The result underscores the importance of media-driven cultural portrayals in fostering curiosity and meaningful engagement with foreign cultures.

Table 4.

Standardized structural estimates (whole samples).

H2: Engagement with Korean culture → intention to visit Korea: A significant positive association was observed between the engagement with Korean culture and intention to visit Korea (standardized estimate = 0.246, critical ratio = 4.266, p < 0.01). This finding highlights that active engagement with Korean culture, often inspired by K-dramas, serves as a crucial motivator for forming travel intentions. By immersing themselves in Korean culture through media-driven activities, participants develop a strong desire to experience Korea firsthand. This relationship aligns with the TPB, where active engagement enhances attitudes and perceived behavioral control, thereby facilitating intention formation.

H3: Engagement with Korean culture → sustainable tourism attitudes: An engagement with Korean culture was positively associated with sustainable tourism attitudes (standardized estimate = 0.477, critical ratio = 7.798, p < 0.01). This underscores the critical role of cultural immersion in promoting eco-conscious and culturally respectful travel behaviors. SEM facilitated the integration of multiple constructs, revealing how cultural engagement fosters personal integrative values tied to sustainability. This supports the UGT, which emphasizes that cultural content, such as K-dramas, fulfills cognitive and personal integrative needs, shaping ethical values related to responsible tourism. These results highlight the importance of the media as a tool for cultivating sustainability-driven travel intentions.

H4: Cultural perception → sustainable tourism attitudes: A significant positive relationship was identified between cultural perception and sustainable tourism attitudes (standardized estimate = 0.222, critical ratio = 3.732, p < 0.01). This finding illustrates that favorable perceptions of Korea’s cultural richness not only inspire admiration but also promote ethical values and responsible tourism behaviors. SEM effectively captured this indirect relationship, showcasing the mediating role of cultural engagement in shaping sustainable attitudes. This result aligns with the TPB, which posits that attitudes toward sustainability are influenced by positive perceptions of the destination.

H5: Sustainable tourism attitudes → intention to visit Korea: Sustainable tourism attitudes were found to significantly predict the intention to visit Korea (standardized estimate = 0.417, critical ratio = 6.887, p < 0.01). This finding demonstrates that individuals who prioritize eco-friendly and culturally respectful travel practices are more likely to plan a trip to Korea. SEM revealed this critical pathway, emphasizing the role of sustainability-focused attitudes in bridging media engagement and travel intentions. The results underscore the importance of incorporating sustainability themes into media content to enhance its influence on behavioral outcomes.

H6: Sustainability messaging moderates the relationship between engagement with Korean culture and sustainable tourism attitudes: Multi-group analysis, a key strength of SEM, was used to evaluate the moderating effect of the sustainability messaging in K-dramas according to the standardized deviation split approach. The sample was split into low (N = 279) and high (N = 275) groups based on participants’ perceptions of the sustainability messaging prominence. Results, detailed in Table 5, reveal the following: In the low group, the relationship between engagement with Korean culture and sustainable tourism attitudes was nonsignificant (standardized estimate = 0.154, critical ratio = 1.839, p > 0.05). This suggests that when sustainability messaging is perceived as less prominent, cultural engagement has a weaker influence on fostering sustainability-related attitudes. However, in the high group, the relationship was significantly stronger (standardized estimate = 0.308, critical ratio = 3.850, p < 0.01), indicating that when sustainability messaging is perceived as prominent, cultural engagement has a greater impact on cultivating eco-conscious travel behaviors. A chi-square difference test (Δχ2 (1) = 3.878, p < 0.05) confirmed that sustainability messaging significantly moderates this relationship. These findings demonstrate that embedding sustainability themes in K-dramas amplifies their effectiveness in promoting sustainable tourism attitudes. The multi-group analysis provided nuanced insights, showcasing the variability in engagement effects based on the perceived prominence of sustainability themes.

Table 5.

Standardized structural estimates (two different groups).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study advances the theoretical understanding by examining the interconnected roles of cultural perception, engagement with Korean culture, sustainable tourism attitudes, and sustainability messaging in shaping the intention to visit Korea. These variables, underpinned by the TPB and UGT, provide a multi-dimensional lens to explore how media consumption influences travel intentions and sustainability-focused behaviors [15,17,20].

The findings underscore cultural perception as a foundational variable influencing behavioral intentions. In line with the TPB, cultural perception reflects individuals’ cognitive and affective evaluations of Korea’s cultural, historical, and societal attributes, which are predominantly shaped by K-drama exposure [1,5]. The strong relationship between cultural perception and engagement with Korean culture highlights how media portrayals of Korea’s landscapes, traditions, and modernity resonate with audiences, fostering admiration and curiosity [2,4]. From a UGT perspective, K-dramas satisfy viewers’ cognitive needs by presenting an enriched understanding of Korean culture [19,22]. This dual theoretical grounding underscores the pivotal role of media in framing cultural perceptions that serve as attitudinal precursors to active engagement and eventual behavioral intentions.

An engagement with Korean culture emerges as a mediating variable that connects cultural perception to behavioral outcomes, including sustainable tourism attitudes and intentions to visit Korea. The significant associations revealed in H2 and H3 confirm that active immersion in cultural activities—such as trying Korean cuisine, learning the language, or exploring Korean traditions—is a direct outcome of favorable cultural perceptions [41,43]. The TPB explains this through the influence of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, where engagement facilitates a transition from passive admiration to active participation [15,16]. Simultaneously, the UGT highlights that cultural engagement fulfills affective needs (emotional connection to narratives) and personal integrative needs (self-identity enhancement) [19,21]. The findings position engagement as a critical conduit for translating media-driven cultural perceptions into actionable travel intentions and eco-conscious behaviors, thus bridging the gap between media exposure and sustainable tourism practices.

Sustainable tourism attitudes represent an ethical dimension of behavioral intentions, capturing predispositions toward eco-friendly, culturally respectful, and socially responsible travel [44,52]. The strong relationships observed in H3 and H5 confirm that the engagement with Korean culture significantly shapes these attitudes, which in turn influence the intention to visit Korea [1,45]. The integration of sustainability themes within the TPB framework broadens its applicability, illustrating that attitudes formed through cultural engagement extend beyond mere travel motivations to encompass ethical considerations. The UGT further complements this by emphasizing how sustainability narratives in K-dramas fulfill personal integrative needs tied to responsible global citizenship [2,49]. This alignment between theoretical constructs and empirical findings highlights the potential of entertainment media to foster not only tourism but also ethical travel practices aligned with sustainability goals.

The role of sustainability messaging in K-dramas as a moderating variable provides novel insights into the nuanced ways media can amplify sustainability-focused behaviors. The findings reveal that when sustainability themes are perceived as prominent, the relationship between engagement with Korean culture and sustainable tourism attitudes is significantly strengthened [4,49]. This moderating effect aligns with the TPB by demonstrating how media content can shape subjective norms, positioning sustainability as a socially desirable and culturally endorsed behavior [15,17]. From a UGT perspective, sustainability messaging fulfills cognitive and affective needs by increasing the awareness and emotional investment in eco-conscious practices [21,22]. This study’s results highlight the strategic potential of embedding sustainability themes in entertainment media to not only enhance viewer engagement but also cultivate ethical and sustainable behaviors among global audiences.

The ultimate dependent variable, the intention to visit Korea, encapsulates the culmination of cultural perceptions, engagement, and sustainability-focused attitudes. Consistent with the TPB, the results affirm that intentions are shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, all influenced by prior media exposure [1,17]. The significant relationship between sustainable tourism attitudes and the intention to visit Korea underscores the importance of aligning tourism motivations with ethical considerations [44,52]. The UGT complements this by showing how K-dramas satisfy psychological needs that translate into concrete travel plans [1,19]. This finding extends the theoretical discourse on media-driven tourism by demonstrating that media content does not merely inspire curiosity but also motivates actionable outcomes, such as planning a trip.

By integrating the TPB and UGT, this study develops a comprehensive theoretical model that bridges the gap between media engagement and sustainable tourism behaviors [15,20]. The TPB provides a predictive framework for understanding behavioral intentions, while the UGT offers a nuanced explanation of the psychological gratifications derived from media consumption. Together, these theories illuminate the interplay between the cognitive, affective, and social mechanisms driving travel intentions and sustainability-focused behaviors. This research advances the theoretical discourse in several ways. First, it demonstrates how entertainment media, specifically K-dramas, can meaningfully influence global perceptions and behavioral intentions [1,5]. Second, it introduces sustainability as a critical dimension in media-driven tourism, addressing an overlooked intersection between entertainment and ethical travel. Finally, by focusing on American audiences, this study broadens the geographic and cultural scope of the existing literature, providing insights into how the media influences diverse populations [1,10].

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study highlight several strategic opportunities for tourism marketers, policymakers, and media content creators to leverage the global popularity of K-dramas in promoting South Korea as a culturally rich and sustainable travel destination. By aligning promotional strategies with the psychological mechanisms identified in this research, stakeholders can foster meaningful cultural connections and drive eco-conscious travel behaviors.

The significant relationship between cultural perception and engagement with Korean culture underscores the role of K-dramas as powerful cultural ambassadors. Tourism boards can capitalize on the immersive depictions of Korea’s traditions, landmarks, and modernity by developing targeted campaigns that connect popular K-drama locations with real-world travel experiences. For instance, iconic series, like Crash Landing on You or Squid Game, have made locations such as Jeju Island and Seoul’s vibrant neighborhoods global attractions. Offering curated travel itineraries, such as “K-Drama Trails”, can deepen the viewers’ connection to these narratives while promoting South Korea as a must-visit destination. Collaborations with streaming platforms like Netflix could enhance this strategy by integrating advertisements or travel packages into streaming interfaces, allowing viewers to seamlessly transition from virtual engagement to real-world exploration.

Sustainability messaging in K-dramas emerges as a critical driver of sustainable tourism attitudes, demonstrating the potential of media narratives to inspire eco-conscious travel behaviors. Incorporating sustainability-focused storylines, such as characters engaging in community-based tourism or promoting the preservation of Korea’s natural landscapes, can enhance the viewers’ awareness and motivation to adopt responsible tourism practices. For example, a drama that highlights eco-tourism in rural Korea or the preservation of traditional tea plantations could inspire audiences to seek similar experiences. These narratives can be supported by promotional campaigns featuring practical travel tips and links to eco-friendly accommodations, providing viewers with actionable steps to align their travel plans with sustainability values. Thus, tourism marketers can leverage K-dramas by identifying filming locations that reflect sustainable practices or cultural authenticity, integrating them into destination campaigns. Content creators may also collaborate with tourism boards to highlight local attractions, traditional lifestyles, and eco-friendly behaviors in their narratives. For example, storylines featuring slow food culture, rural ecotourism, or heritage preservation can serve both artistic and promotional goals. These coordinated efforts can encourage more responsible tourism while enhancing viewer engagement.

American audiences, as a key demographic for K-drama consumption, offer significant opportunities for tailored engagement. Marketing campaigns can tap into their preferences for experiential and culturally enriching travel by creating interactive platforms that combine K-drama narratives with immersive travel experiences. For instance, virtual reality tours of popular filming locations or social media challenges inspired by K-drama themes could engage this audience effectively. Partnerships with influencers or travel agencies to promote themed packages—such as food tours featuring traditional Korean markets or visits to Hanok villages—can further enhance the appeal of South Korea as a travel destination.

The accessibility of K-dramas through OTT platforms, like Netflix and Viki, has played a pivotal role in shaping cultural perceptions and travel intentions. To deepen this impact, tourism organizations could collaborate with these platforms to produce supplementary content, such as behind-the-scenes features, mini-documentaries on Korean history, or interactive guides to destinations depicted in dramas. These additions can enhance the viewers’ perceived behavioral control by providing practical travel information, thereby increasing their confidence and likelihood of visiting Korea.

Cross-sector collaborations between tourism stakeholders and media creators are vital for amplifying the impact of K-drama-inspired tourism. Joint initiatives can include co-branded campaigns, on-location cultural festivals, and exclusive tours designed around specific dramas. Additionally, implementing a “K-Drama Green Tourism Certified” program could promote eco-friendly practices within the tourism industry while appealing to environmentally conscious travelers. Such collaborations not only boost tourism but also ensure that the benefits extend to local communities, supporting community-based tourism and fair-trade initiatives.

Educational programs and awareness campaigns also represent significant potential in promoting responsible tourism behaviors. Workshops featuring K-drama actors discussing sustainability themes or interactive webinars on eco-friendly travel practices can inspire audiences to adopt ethical travel habits. Digital guides embedded in travel apps or promoted alongside streaming content could provide tourists with tips on reducing their environmental footprint, respecting local cultures, and supporting local businesses, thereby reinforcing the alignment between media engagement and sustainability.

Finally, monitoring and measuring the impact of K-drama-inspired tourism through feedback mechanisms is crucial for refining strategies and sustaining momentum. Surveys and AI-driven analytics can track how media content influences travel behaviors and sustainability attitudes, offering valuable insights for future campaigns. By integrating these insights with media content, stakeholders can continuously evolve their approaches, ensuring that the transformative potential of K-dramas in promoting cultural diplomacy and sustainable tourism remains impactful.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

While this study offers valuable insights into the influence of K-dramas on American audiences’ travel intentions and sustainability attitudes, certain limitations highlight opportunities for further research. First, the focus on American consumers limits the generalizability of findings to other cultural or geographic contexts. Future research should explore diverse populations, such as audiences in Europe, Southeast Asia, or the Middle East, to examine whether similar relationships hold across cultural boundaries.

While this study included a range of age and income groups, the sample may still lack sufficient demographic diversity. Future research should aim for greater representativeness by ensuring a balanced inclusion of participants across various age groups, income levels, and educational backgrounds to enhance the external validity.

The cross-sectional design of this study restricts causal inferences, as it captures only a snapshot of the relationships among variables. To establish causality, future research could adopt experimental designs that manipulate the exposure to sustainability-themed media content. For example, studies could compare groups exposed to K-dramas with strong sustainability messaging versus those with neutral content to assess their differential impact on sustainability attitudes and travel intentions. Additionally, longitudinal studies are needed to track how sustained engagement with K-dramas shapes cultural perceptions, sustainability attitudes, and actual travel behaviors over time.

This study relied on participants’ subjective perceptions of sustainability messaging, which may vary based on individual interpretations. Incorporating the content analysis of K-dramas to objectively assess the presence of sustainability themes could strengthen future investigations. Additionally, while intentions to visit Korea were the primary behavioral outcome, future research should examine the gap between intentions and actual travel behaviors, considering factors like financial constraints or travel restrictions.

Other moderating factors, such as personal values, environmental awareness, and prior travel experiences, were not explored in this study. Examining these variables could reveal more nuanced dynamics between media engagement, cultural perceptions, and travel intentions. Furthermore, as technology evolves, emerging platforms, like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), could transform media-driven tourism. Future research should investigate how these innovations enhance cultural engagement and promote sustainable tourism behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-M.C.; Methodology, H.-M.C.; Investigation, H.-M.C.; Data curation, H.-M.C.; Writing—original draft, H.-M.C.; Writing—review and editing, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to South Korean regulations, specifically the Bioethics and Safety Act Enforcement Rules, ethical approval is not required for this type of study as it does not involve face-to-face interaction, physical intervention, or the collection of identifiable personal information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beaugeard, E.; Cho, H.D.; Koo, C. When K-Drama Fiction Becomes Reality: The French Perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Perceived Values of TV Drama, Audience Involvement, and Behavioral Intention in Film Tourism. In Visual Media and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-003-16941-3. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y. How Media Reported on Korean Wave?: Focusing on the Analysis of News Coverage of Republic of Korea. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2022, 51, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.; Park, J.H.; Ko, E. The Effect of Attributes of Korean Trendy Drama on Consumer Attitude, National Image, and Consumer Acceptance Intention for Sustainable Hallyu Culture. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Husin, N.A.; Ramlee, N.Z. South Korea Film-Induced Tourism: The K-Drama Determinant for Malaysian Tourists. In Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Cross-Border Trade and Business; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 27–45. ISBN 978-1-7998-9071-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, M.; Kim, D.; Baek, H. More than Just a Fan: The Influence of K-Pop Fandom on the Popularity of K-Drama on a Global OTT Platform. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 31, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J. New Directions in K-Drama Studies. J. Jpn. Korean Cine. 2022, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titania, D.D.M.; Haryanto, J.O. A Study of Korean Drama and Indonesian Teenager’s Perception on Images of South Korea as a Potential Tourist Destination. Manaj. Dan Bisnis 2022, 21, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Tourism Data Lab Characteristics of Foreign Tourists Visiting Korea. Available online: https://datalab.visitkorea.or.kr/datalab/portal/nat/getForTourDashForm.do# (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Pablo, F.B., IV; David, J.D.; Ambrosio, P.S. Mediating Effect of Perceived Destination Image between K-Dramas’ Motivational Influence and Visit Intention to South Korea/Felipe B.Pablo IV, Joy DC. David and Patricia S. Ambrosio. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2022, 14, 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Han, H. Effects of TV Drama Celebrities on National Image and Behavioral Intention. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Promoting Destinations via Film Tourism: An Empirical Identification of Supporting Marketing Initiatives. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Richardson, S.L. Motion Picture Impacts on Destination Images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukendi, J.; Siregar, R.K.; Wansaga, S.C.; Gunadi, W. Influencing Factors of K-Drama Satisfaction and Their Impacts on Fanaticism and Behavioral Intention. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2023, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 438–459. [Google Scholar]

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A Systematic Literature Review of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management Research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-W.; An, Y.; Norman, W. Exploring the Application of the Uses and Gratifications Theory as a Conceptual Model for Identifying the Motivations for Smartphone Use by E-Tourists. Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2022, 3, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.J.; Jeong, C. The Role of Social Media Engagement in the Purchase Intention of South Korea’s Popular Media (Hallyu) Tourism Package: Based on Uses and Gratifications Theory. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Xue, Y. Advancing Tourism Recovery through Virtual Tourism Marketing: An Integrated Approach of Uses and Gratifications Theory and Attachment to VR. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Khan, I.; Hasan, R. Exploring Tourists’ Virtual Reality-Based Brand Engagement: A Uses-and-Gratifications Perspective. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Finer-Grained Understanding of Travel Livestreaming Adoption: A Synthetic Analysis from Uses and Gratifications Theory Perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 47, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Choi, L. The Role of Attachment to K-Celebrity from a Destination Marketing Perspective. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 19, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Jittithavorn, C.; Lee, T.J.; Chen, X. Contribution of TV Dramas and Movies in Strengthening Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Park, B.; Choi, H. The Phenomenon and Development of K-Pop: The Relationship between Success Factors of K-Pop and the National Image, Social Network Service Citizenship Behavior, and Tourist Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Ham, S.; Kim, D. The Effects of Likability of Korean Celebrities, Dramas, and Music on Preferences for Korean Restaurants: A Mediating Effect of a Country Image of Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Long, P.; Robinson, M. Small Screen, Big Tourism: The Role of Popular Korean Television Dramas in South Korean Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2009, 11, 308–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Song, H.; Lee, C.-K.; Petrick, J.F. An Integrated Model of Pop Culture Fans’ Travel Decision-Making Processes. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J. Transnationalization of Korean Popular Culture and the Rise of “Pop Nationalism” in Korea. J. Pop. Cult. 2011, 44, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blechman, B.M. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Political Sci. Q. 2004, 119, 680–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, D.C. Parasocial Interaction: A Review of the Literature and a Model for Future Research. Media Psychol. 2002, 4, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R.R. Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yhee, Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, J.-Y.; Koo, C. Sustainable Tourism Cities: Linking Idol Attachment to Sense of Place. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yoo, M. Examining Celebrity Fandom Levels and Its Impact on Destination Loyalty. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Giouvris, E. Tourist Arrivals in Korea: Hallyu as a Pull Factor. In Current Issues in Asian Tourism: Volume II; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-003-13356-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Agrusa, J.; Chon, K.; Cho, Y. The Effects of Korean Pop Culture on Hong Kong Residents’ Perceptions of Korea as a Potential Tourist Destination. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Kang, S.K.; Ahmad, M.S.; Park, Y.-N.; Park, E.; Kang, C.-W. Role of Cultural Worldview in Predicting Heritage Tourists’ Behavioural Intention. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.; Park, H.S. Culture and the Theory of Planned Behaviour: Organ Donation Intentions in Americans and Koreans. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2010, 4, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Jung, M.; Nathan, R.J.; Chung, J.-E. Cross-National Study on the Perception of the Korean Wave and Cultural Hybridity in Indonesia and Malaysia Using Discourse on Social Media. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, T.M.; Kiatkawsin, K. Beauty and Celebrity: Korean Entertainment and Its Impacts on Female Indonesian Viewers’ Consumption Intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, S. UGC Sharing Motives and Their Effects on UGC Sharing Intention from Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives: Focusing on Content Creators in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayaban, C.J.G.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Mariñas, K.A.; Nadlifatin, R.; Borres, R.D.; Gumasing, M.J.J. Factors Affecting Filipino Consumer Behavior with Korean Products and Services: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, N.; Khan, M.N.; Ahuja, V. Intention to Adopt User Generated Content on Virtual Travel Communities: Exploring the Mediating Role of Attitude. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2023, 23, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.T.; Sharmin, F.; Badulescu, A.; Stiubea, E.; Xue, K. Travelers’ Responsible Environmental Behavior towards Sustainable Coastal Tourism: An Empirical Investigation on Social Media User-Generated Content. Sustainability 2021, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, J.; Yoon, S. Evaluating the Relationship between Perceived Value Regarding Tourism Gentrification Experience, Attitude, and Responsible Tourism Intention. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Reisinger, Y.; Ahmad, M.S.; Park, Y.-N.; Kang, C.-W. The Influence of Hanok Experience on Tourists’ Attitude and Behavioral Intention: An Interplay between Experiences and a Value-Attitude-Behavior Model. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Applying Uses and Gratifications Theory and Social Influence Processes to Understand Students’ Pervasive Adoption of Social Networking Sites: Perspectives from the Americas. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Zhang, L.; Line, N.; McGinley, S. When Less Is More: Sustainability Messaging, Destination Type, and Processing Fluency. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 58, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. A Study of Event Quality, Destination Image, Perceived Value, Tourist Satisfaction, and Destination Loyalty among Sport Tourists. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-S.C.; Sirakaya, E. Measuring Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Tourism: Development of Sustainable Tourism Attitude Scale. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Crouch, G.I.; Long, P. Environment-Friendly Tourists: What Do We Really Know About Them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of Enterprise Systems: The Effect of Institutional Pressures and the Mediating Role of Top Management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Kim, Y. On the Relationship between Coefficient Alpha and Composite Reliability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).