Urban Greening and Local Planning in Italy: A Comparative Study Exploring the Possibility of Sustainable Integration Between Urban Plans

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Italian Experience

2. Materials and Methods

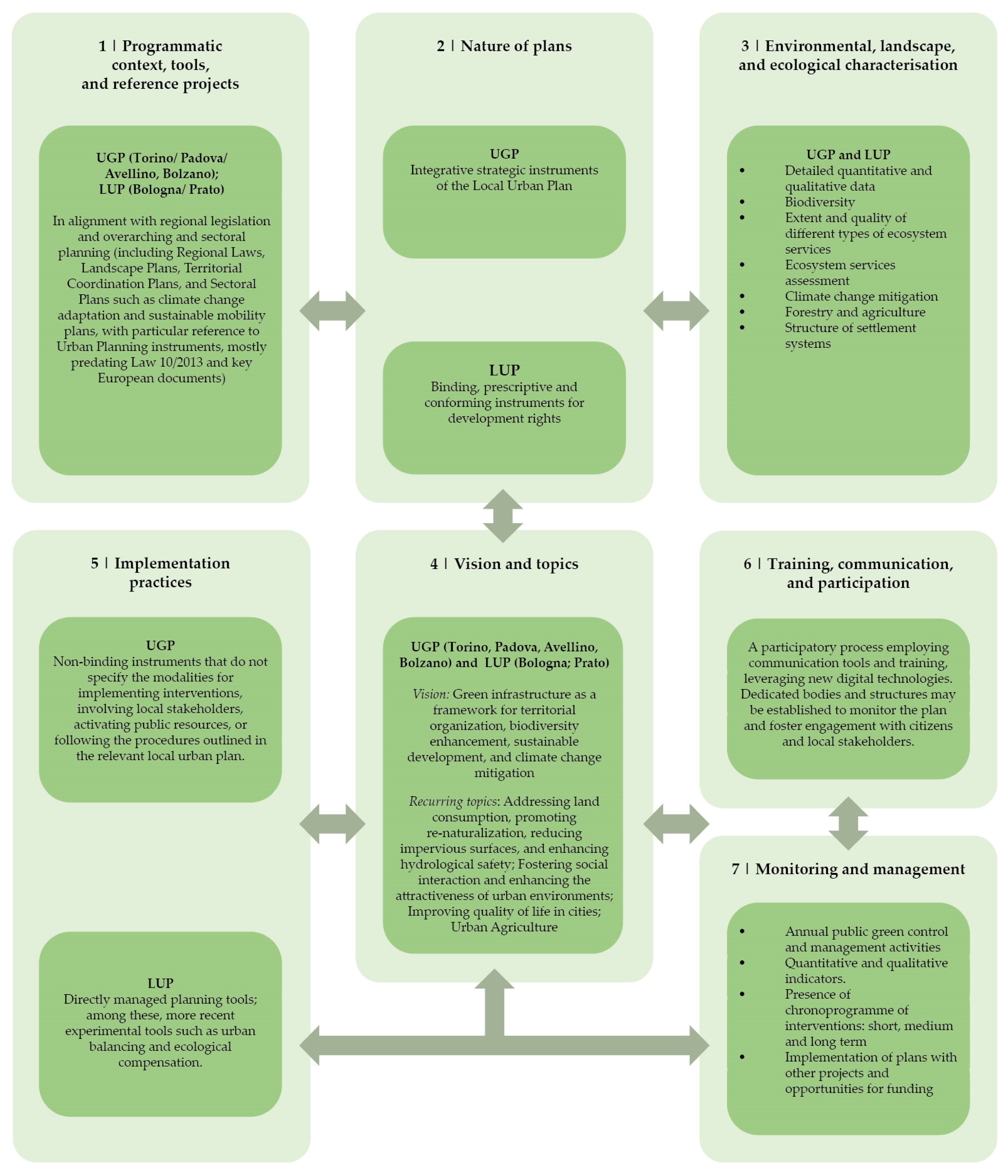

- Programmatic context, tools, and reference projects: Identification of key regional legislation and the core themes within sustainable development strategies.

- Nature of the plans: Examining how the natural component is integrated within urban development strategies (e.g., greenbelts; green infrastructure as a basis for the urban structure; sponge cities, etc.).

- Environmental, landscape, and ecological characterisation: Assessment of the current state of nature and biodiversity; planning elements’ quantitative evaluation of vegetation, the various functions of green space, the services provided, and associated risks; inventory of relevant policies and strategies).

- Vision and topics: Definition of goals, short- and long-term actions, and related indicators; integration with other instruments, such as the Services Plan, the Sustainable Mobility Plan, the Climate Adaptation Plan, etc.

- Training, communication, and participation: Details of the implementation of participatory design processes and communication and awareness-raising strategies.

- Implementation practices: Exploration of the proposed implementation mechanisms and the identification of necessary resource acquisition strategies.

- Monitoring and management: Selection of a monitoring and reporting system to evaluate the aims and results achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Programmatic Context, Tools, and Reference Projects

3.2. Nature of the Plans

3.3. Environmental, Landscape, and Ecological Characterisation

3.4. Vision and Topics

3.5. Training, Communication, and Participation

3.6. Implementation Procedures

3.7. Monitoring and Management

4. Discussion

- Applying the operational requirements of LUPs for the proper management of the land regime to encourage public–private partnerships for the implementation of green spaces [33,66]. Careful planning of the resources required and identification of sustainable sources of funding are therefore crucial [67].

5. Conclusions

- develop a framework of knowledge about nature and biodiversity and its valuation, using new methods of investigation (ecosystem services, climate scenarios, etc.);

- develop a planning vision of sustainability goals with related indicators;

- agree with the various sectors of the public administration on priorities, actions, responsibilities, and timeframes to be respected in the implementation of green works;

- use tools to make urban areas more equal and to compensate for the environment to encourage the creation of green areas by limiting the use of public resources;

- create a communication, education, and public awareness strategy; set up a system to monitor, report, and evaluate things through the use of methods whereby citizens can take part in research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNP | Urban nature plan |

| UGP | Urban greening plan |

| GSR | Green space regulation |

| LUP | Local urban plan |

| SUMP | Sustainable urban mobility plan |

| SECAP | Sustainable energy and climate action plan |

| NBS | Nature-Based Solutions |

| ISPRA | Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

References

- Mensah, C.A.; Andres, L.; Perera, U.; Roji, A. Enhancing quality of life through the lens of green spaces: A systematic review approach. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckelshauß, T. The effect of green areas on life satisfaction: A comparison of subjective and objective measures. In Handbook on Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment; Maddison, D., Rehdanz, K., Welsch, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, A. Sustainable development and proximity city. The environmental role of new public spaces. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2024, 17, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, M.; Cruz, S.; Monteiro, A.; Neset, T.S. Designing urban green spaces for climate adaptation: A critical review of research outputs. Urban Clim. 2022, 42, 101126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Liu, W.; Gan, T.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q. A review of mitigating strategies to improve the thermal environment and thermal comfort in urban outdoor spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mell, I. Examining the Role of Green Infrastructure as an Advocate for Regeneration. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 731975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenheer, D. Urban Regeneration and Green Space Sistem: São Paulo Metropolitan Area. In Design for Health. UIA 2023. Sustainable Development Goals Series; Hasan, A., Benimana, C., Ramsgaard Thomsen, M., Tamke, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva Cortés, P. The External Impact of the Green Economy: An Analysis of the Environmental Implications of the Green Economy; IPE Working Papers 56/2015; Berlin School of Economics and Law, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE): Berlin, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://www.ipe-berlin.org/fileadmin/institut-ipe/Dokumente/Working_Papers/ipe_working_paper_56.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Alves, F.; Costa, P.M.; Novelli, L.; Vidal, D.G. The rights of nature and the human right to nature: An overview of the European legal system and challenges for the ecological transition. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1175143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, C. Green Unionism and Human Rights: Imaginings beyond the Green New Deal. Pace Environ. Law Rev. 2023, 40, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Riveros, R.; Altamirano, A.; De La Barrera, F.; Rozas-Vásquez, D.; Vieli, L.; Meli, P. Linking public urban green spaces and human well-being: A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mears, M.; Brindley, P.; Jorgensen, A.; Maheswaran, R. Population-level linkages between urban greenspace and health inequality: The case for using multiple indicators of neighbourhood greenspace. Health Place 2020, 62, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Carrus, G.; Sanesi, G.; Davies, C. Benefits and well-being perceived by people visiting green spaces in periods of heat stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltynowski, M. Urban green spaces in land-use policy-types of data, sources of data and staff-the case of Poland. Land Use Policy 2023, 127, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuste, J. The Green City: General Concept. In Making Green Cities: Concepts, Challenges and Practice; Breuste, J., Artmann, M., Ioja, C., Qureshi, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Environment. In EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030-Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en#documents] (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- European Commission. Urban Nature Platform. Supporting Towns and Cities in Restoring Nature and Biodiversity. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/urban-environment/urban-nature-platform_en#urban-nature-plan-guidance-and-toolkit (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Giannico, V.; Spano, G.; Elia, M.; D’Este, M.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Green spaces, quality of life, and citizen perception in European cities. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICLEI. Tackling the Climate and Biodiversity Crises in Europe Through Urban Greening Plans; Scientific Opinion Paper/October 2021; Umwelt Bundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://iclei-europe.org/publications-tools/?c=search&uid=iLn4nemY (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- EUROPARC Federetion. About Urban Greening Plans. Available online: https://www.europarc.org/about-urban-greening-plans/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Aubert, G. How Much Will the Implementation of the Nature Restoration Law Cost and How Much Funding Is Available? Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://ieep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/4_-Nature-Restoration-Law-and-Funding.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Bellè, B.M.; Deserti, A. Urban Greening Plans: A Potential Device towards a Sustainable and Co-Produced Future. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltynowski, M.; Kronenberg, J.; Bergier, T.; Kabisch, N.; Łaszkiewicz, E.; Strohbach, M.W. Challenges of urban green space management in the face of using inadequate data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.E.; Neuhuber, T.; Zawadzki, W. Understanding citizens’ willingness to contribute to urban greening programs. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 95, 128293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATTM, Ministero dell’Ambiente e Della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare-Comitato per lo Sviluppo del Verde Pubblico. Linee Guida per il Governo Sostenibile del Verde Urbano. Del. No. 19-03/07/2017. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/pagina/comitato-lo-sviluppo-del-verde-pubblico (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- MATTM, Ministero dell’Ambiente e Della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare-Comitato per lo Sviluppo del Verde Pubblico. Strategia Nazionale del Verde Pubblico. 2018. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio/allegati/comitato%20verde%20pubblico/strategia_verde_urbano.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025). (In Italian)

- Chiesura, A.; D’Ambrogi, S.; Pileri, P.; Bultrini, M.; De Maio, E.; Faticanti, M.; Giardi, G.; Lepore, A.; Bataloni, S.; Baldini, B.; et al. I Piani Comunali del Verde: Strumenti per Riportare la Natura Nella Nostra Vita? Quaderno ISPRA 33/2024; ISPRA: Roma, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/pubblicazioni/quaderni/ambiente-e-societa/i-piani-comunali-del-verde-strumenti-per-riportare-la-natura-nella-nostra-vita (accessed on 10 December 2024). (In Italian)

- OECD. Developing an Integrated Approach to Green Infrastructure in Italy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogliani, L.; Ronchi, S.; Arcidiaco, A.; Di Martino, V.; Mazza, F. Regeneration in an ecological perspective. Urban and territorial equalisation for the provision of ecosystem services in the Metropolitan City of Milan. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, S.; Arcidiacono, A.; Pogliani, L. Integrating green infrastructure into spatial planning regulations to improve the performance of urban ecosystems. Insights from an Italian case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto Interministeriale 2 April 1968, No. 1444. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/1968_1444.htm (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Pelorosso, R.; Gobattoni, F.; Leone, A. Increasing Hydrological Resilience Employing Nature-Based Solutions: A Modelling Approach to Support Spatial Planning. In Smart Planning: Sustainability and Mobility in the Age of Change. Green Energy and Technology; Papa, R., Fistola, R., Gargiulo, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaimo, C. Tra Spazio Pubblico e Rigenerazione Urbana. Il Verde Come Infrastruttura per la Città Contemporanea. Urbanistica Dossier Online 2020; Volume 17. Available online: http://www.urbanisticainformazioni.it/IMG/pdf/ud017.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Lanzani, A. L’Italia degli standard urbanistici. Che fare, oggi? Territorio 2019, 90, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaimo, C. Dagli standard urbanistici a verde alle performance urbane. In Proceedings of the Il Verde Urbano Come Motore di Rigenerazione Cittadina, Urbanpromogreen, Venezia, Italy, 17–18 September 2019; Available online: https://urbanpromo.it/2019/eventi/il-verde-urbano-come-motore-di-rigenerazione-cittadina/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Giaimo, C. La trama. Dopo 50 anni ripartire dagli standard. In Dopo 50 Anni di Standard Urbanistici in Italia; Giaimo, C., Ed.; INU Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Giaimo, C.; Tosi, M.C.; Voghera, A. Tecniche urbanistiche per una fase di decrescita. In Proceedings of the Downscaling, Rightsizing. Contrazione Demografica e Riorganizzazione Spaziale, Torino, Italy, 17–18 June 2021; Planum Publisher-SIU: Roma-Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge 14 January 2019, No. 10. Norme per lo Sviluppo Degli Spazi Verdi. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:2013;10 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- European Commission. Urban Nature Plans. Guidance for Cities to Help Prepare an Urban Nature Plan; EU Publications: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Ambiente Urbano-Anno 2022. Available online: https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/ambiente-urbano-anno-2022-2/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Calabrò, M.; De Biase, C. Il governo del territorio nel confronto tra saperi: Note su una prospettiva funzionale della pianificazione del verde urbano. Riv. Quadrimestrale Dirit. Dell’ambiente 2024, 1, 185–212. Available online: https://www.rqda.eu/en/marco-calabro-claudia-de-biase-il-governo-del-territorio-nel-confronto-tra-saperi-note-su-una-prospettiva-funzionale-della-pianificazione-del-verde-urbano/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Comune di Bologna. PUG. Piano Urbanistico Generale di Bologna. Available online: https://cantierebologna.com/2023/08/18/il-caldo-come-la-pandemia-le-strategie-di-adattamento-del-comune-di-bologna/e (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Comune di Prato. POC. Piano Operativo Comunale. Available online: https://www.greencitynetwork.it/portfolio_page/prato-dal-piano-operativo-tra-riuso-e-natura-allurban-jungle/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Barberis, V. Towards the Harmonic City. In Harmonic Innovation; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Cicione, F., Filice, L., Marino, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Torino. Piano Strategico del Verde di Torino. Available online: http://www.comune.torino.it/verdepubblico/il-verde-a-torino/piano-infrastruttura-verde/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Comune di Bolzano. Piano del Verde di Bolzano. Available online: https://opencity.comune.bolzano.it/Documenti-e-dati/Documenti-tecnici-di-supporto/Piano-del-verde-di-Bolzano (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Comune di Avellino. Piano del Verde di Avellino. Available online: https://www.comune.avellino.it/piano_del_verde/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Comune di Padova. Piano del Verde di Padova. Available online: https://www.comune.padova.it/piano-verde-comunale (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Mostafavi, M.; Najle, C. Landscape Urbanism: A Manual for the Machinic Landscape; Architectural Association: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prato Forest City. Available online: https://www.pratoforestcity.it (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- WHO. Urban Green Spaces and Health. A Review of the Evidence; World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/345751 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Miceli, E. La Gestione dei Piani Urbanistici. Perequazione, Accordi, Incentivi; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bonavero, F.; Cassatella, C. Per un progetto delle compensazioni ambientali. Il contributo di una visione sovralocale nelle procedure di valutazione della Città metropolitana di Torino. In Proceedings of the Planning-Evaluation. Le Valutazioni nel Processo di Pianificazione e Progettazione. XXIV Conferenza Nazionale SIU Dare Valore ai Valori in Urbanistica, Torino, Italy, 23–24 June 2022; Planum Publisher-SIU: Roma-Milano, Italy, 2023; pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Russo, M. La valutazione come parte del processo pianificatorio e progettuale. In Proceedings of the Planning-Evaluation. Le Valutazioni nel Processo di Pianificazione e Progettazione. XXIV Conferenza Nazionale SIU Dare Valore ai Valori in Urbanistica, Torino, Italy, 23–24 June 2022; Planum Publisher-SIU: Roma, Italy, 2023; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Green City Network. Carta per la Rigenerazione Urbana delle Green City. Available online: https://www.greencitynetwork.it/wp-content/uploads/Carta-per-la-rigenerazione-urbana-delle-gren-city-1.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Comune di Prato. Prato Urban Jungle. Available online: https://www.pratourbanjungle.it/it/pagina1943.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Coppola, E. E se il piano del verde divenisse parte integrante del piano urbanistico comunale? BDC Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2021, 21, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorst, H.; van der Jagt, A.; Raven, R.; Runhaar, H. Urban greening through nature-based solutions—Key characteristics of an emerging concept. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, D.; Pappalardo, V. Planning for spatial equity. A performance-based approach for sustainable urban drainage systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costadone, L.; Vierikko, K. Are traditional urban greening actions compliant with the European Greening Plans guidance? Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 90, 128131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galuzzi, P.; Vitillo, P. Rigenerare le Città. La Perequazione Urbanistica Come Progetto; Maggioli Editore: Milan, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cortinovis, C.; Geneletti, D. A performance-based planning approach integrating supply and demand of urban ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 201, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgo, J.; Cruz, S.S.; Conceição, P. Nature-based solutions in spatial planning and policies for climate change adaptation: A literature review. Ambio 2024, 53, 1599–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, G. The Green and Blue Infrastructure Projects in Spatial Planning as a Key Component for Adaptation to Climate Change. In Green Infrastructure Planning Strategies and Environmental Design; Giudice, B., Novarina, G., Voghera, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. vii–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Gielen, D.; van der Krabben, E. Public Infrastructure, Private Finance: Developer Obligations and Responsibilities, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanghellini, S. Un approccio integrato alla rigenerazione urbana. Urbanistica 2017, 160, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

| Minimum Content | Implementation and Monitoring |

|---|---|

| Environmental and landscape characterisation of the various sectors within the municipal territory, delineated via ecological classification. | Relationship with other urban and sectoral plans (Services Plan, Traffic Plan, General Urban Plan for underground services, etc.). |

| Typological classification of vegetation structures (arboreal and shrub vegetation/herbaceous vegetation) and functional classification of municipal green spaces (accessible/non-accessible). | Programmatic indications for the three-year public works plan. |

| Estimation of the value of urban green spaces through the use of indicators. | Operational projects and design solutions to be implemented in the short to medium term with identified financial resources. |

| Analysis of the needs and ‘demand’ for ecosystem services. | Definition of indicators to monitor the plan’s development and the achievement of its set aims. |

| Analysis of the existing flora and vegetation in terms of qualitative and quantitative evaluation. | Funding mechanisms and resource procurement for the implementation of the identified design solutions. |

| Planning of new green areas and new green infrastructures, as well as peripheral areas, with potential for urban green space expansion. | Information and communication plan for the engagement, participation and sensitisation of citizens. |

| Criteria for the construction of new green infrastructures. |

| Guidelines Law n. 10/2013 | Urban Nature Plan Guidelines. Cycle Steps. | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge |

| Step 5 Current state of nature and biodiversity. |

| Directions, Provisions, and Implementation |

| Step 6 Establishing goals/actions and related indicators. |

| Resource Procurement |

| Step 7 Agreeing on priorities, actions, responsibilities, timelines, and funding. |

| Training and Communication |

| Step 8 Developing a strategy for public communication, education, and awareness. |

| Monitoring and Management |

| Step 9 Establishing a system for monitoring, reporting, and evaluation. Step 10 Adopting and implementing the plan. |

| UGP-LUP | Reference Law | Topics |

|---|---|---|

| Padova UGP |

|

|

| Bolzano UGP |

|

|

| Avellino UGP |

|

|

| Torino UGP |

|

|

| Prato LUP |

|

|

| Bologna LUP |

|

|

| UGP-LUP | Purposes and Aims of the Plan |

|---|---|

| Padova UGP |

|

| Bolzano UGP |

|

| Avellino UGP |

|

| Torino UGP |

|

| Prato LUP |

|

| Bologna LUP |

|

| UGP-LUP | Environmental, Landscape, and Ecological Characterisation |

|---|---|

| Padova UGP |

|

| Bolzano UGP |

|

| Avellino UGP |

|

| Torino UGP |

|

| Prato LUP |

|

| Bologna LUP |

|

| UGP-LUP | Topics | Vision |

|---|---|---|

| Padova UGP |

| Macro-strategies for:

|

| Bolzano UGP |

| Design guidelines:

|

| Avellino UGP |

|

|

| Torino UGP |

|

|

| Prato LUP |

|

|

| Bologna LUP |

|

|

| UGP-LUP | Participation Activities |

|---|---|

| Padova UGP | Actions targeting specific technical stakeholders (institutions, professional associations, etc.), various social, cultural, and sports groups, and neighbourhood councils. Promotion of citizen science. |

| Bolzano UGP | Implementation of six workshops and establishment of three thematic tables: (i) water system; (ii) built-up area; and (iii) peri-urban green spaces. |

| Avellino UGP | Establishment of an environmental consultation body, promotion and communication through the implementation of a municipal website; design workshops and idea competitions, environmental education activities, communication plan. |

| Torino UGP | Establishment of a Municipal Office for Participation and Citizenship; public awareness and communication actions. |

| Prato LUP | Creation of a relational path between actors through the use of new technologies: Prato Forest city project. |

| Bologna LUP | Involvement of stakeholders in the drafting of the Local Urban Plan. |

| UGP-LUP | Implementation Procedures |

|---|---|

| Padova UGP | The UGP is integrated with other existing planning and programming documents, including the ULP. It refers to these for implementation |

| Bolzano UGP | Allocation of dedicated economic resources to the UGP from the Municipal Budget. State funding |

| Avellino UGP | Planning and development of green areas through the LUP in urban transformation areas |

| Torino UGP | Activation of strategic public–private partnerships |

| Prato LUP | Public land transfers in urban transformation areas |

| Bologna LUP | Urban and building scale requirements |

| UGP-LUP | Monitoring | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Padova UGP | The UGP stipulates the definition of several indicators and actions aimed at verifying its implementation. The Plan proposes methods to monitor the following planning objectives: environmental function; biodiversity; functions, accessibility, and functionality of green spaces. | Conducted in two phases: an evaluation of the plan’s implementation five years after its approval, followed by assessments at the 10- and 20-year marks to verify the ongoing alignment with the plan’s vision. |

| Bolzano UGP | The use of both quantitative and qualitative indicators is employed. The evaluation outcomes, ranging from ‘very poor’ to ‘excellent’, are presented on a dedicated map and also disaggregated by the main urban public parks. | The evaluation refers to the recent Minimum Environmental Criteria for sustainable urban green space management. |

| Avellino UGP | A multidimensional monitoring framework is in place, encompassing indicators such as: green balance, tree inventory, number of areas adopted by community groups, tree canopy renewal rate, play equipment provision, green jobs, and staff specialization index. | Interventions are divided into short-, medium-, and long-term phases. Over the five-year period, areas with potential for transformation into public green spaces or urban forests are to be assessed. The UGP encompasses a comprehensive maintenance plan and a general programming plan. |

| Torino UGP | For each strategic line, different lines of action are outlined, each accompanied by specific monitoring indicators. | Involvement of private entities is envisaged for both the development of new green areas, play areas, sports facilities, and urban gardens and maintenance activities. Urban forestry represents a particularly promising area for private sector engagement. |

| Prato LUP | For the three pilot project areas, benefits are estimated for the first 20 years following the plan’s implementation. | Co-design activities will be carried out during the design and implementation phases, involving collaboration with various stakeholders in the creation and maintenance of green spaces. |

| Bologna LUP | Achievement and verification of the predefined objectives in the LUP (surface areas and number of trees) over a ten-year period from the approval year. | Development of climate change scenarios and community engagement sessions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Onofrio, R.; Bocca, A.; Camaioni, C. Urban Greening and Local Planning in Italy: A Comparative Study Exploring the Possibility of Sustainable Integration Between Urban Plans. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073227

D’Onofrio R, Bocca A, Camaioni C. Urban Greening and Local Planning in Italy: A Comparative Study Exploring the Possibility of Sustainable Integration Between Urban Plans. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073227

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Onofrio, Rosalba, Antonio Bocca, and Chiara Camaioni. 2025. "Urban Greening and Local Planning in Italy: A Comparative Study Exploring the Possibility of Sustainable Integration Between Urban Plans" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073227

APA StyleD’Onofrio, R., Bocca, A., & Camaioni, C. (2025). Urban Greening and Local Planning in Italy: A Comparative Study Exploring the Possibility of Sustainable Integration Between Urban Plans. Sustainability, 17(7), 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073227