Depopulation and the Development of Peri-Urban Green Areas of Large Cities: Lessons Learned from Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology and Resources

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Romania’s Population Dynamics in a European and Regional Context

3.2. Depopulation and Demographic Increases in Romania: Regional Differences

3.3. Case Studies Analysis

3.3.1. Some Conceptual Delimitation with Particularization in Romania

3.3.2. Bucharest and Its Peri-Urban Crown

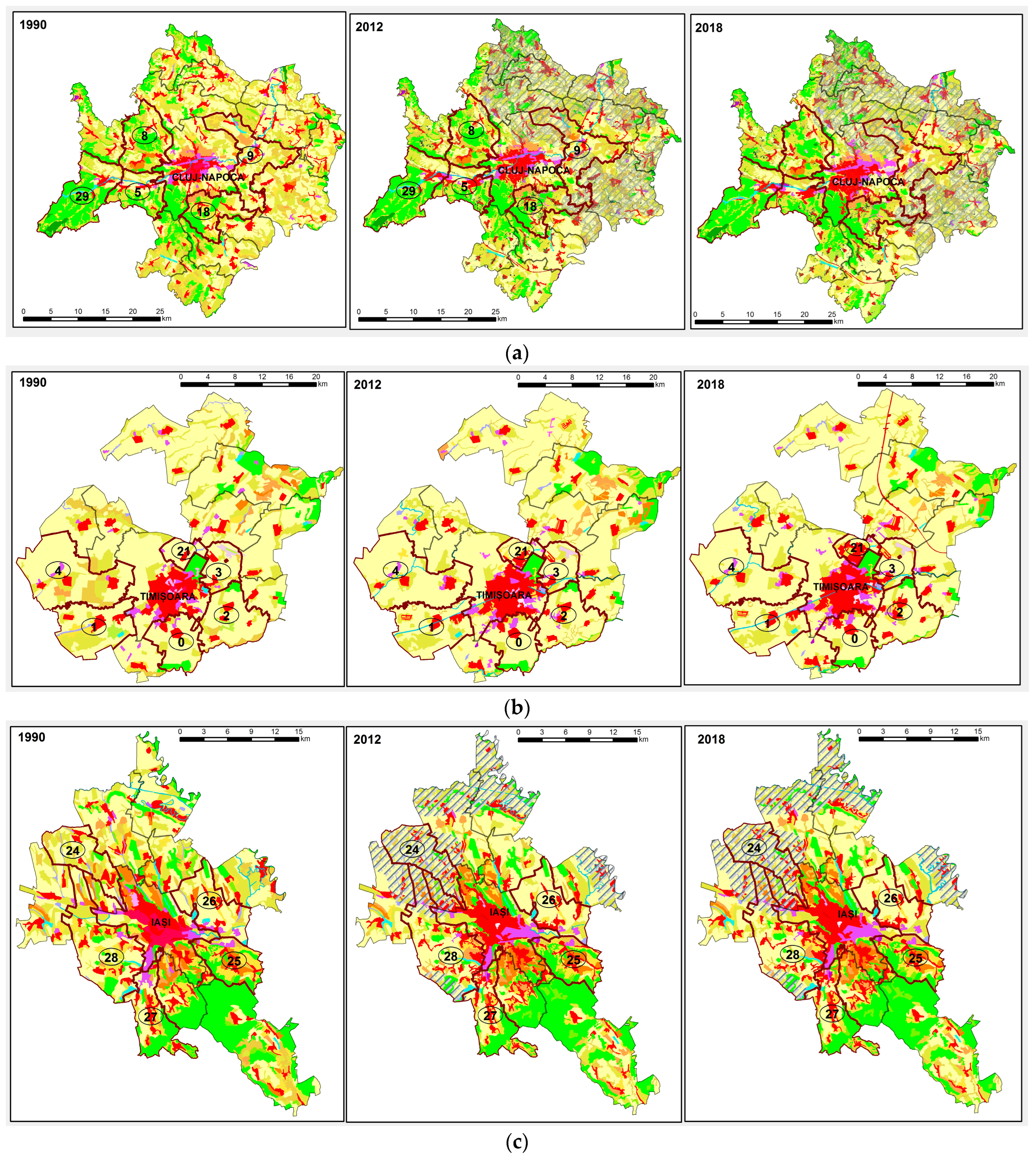

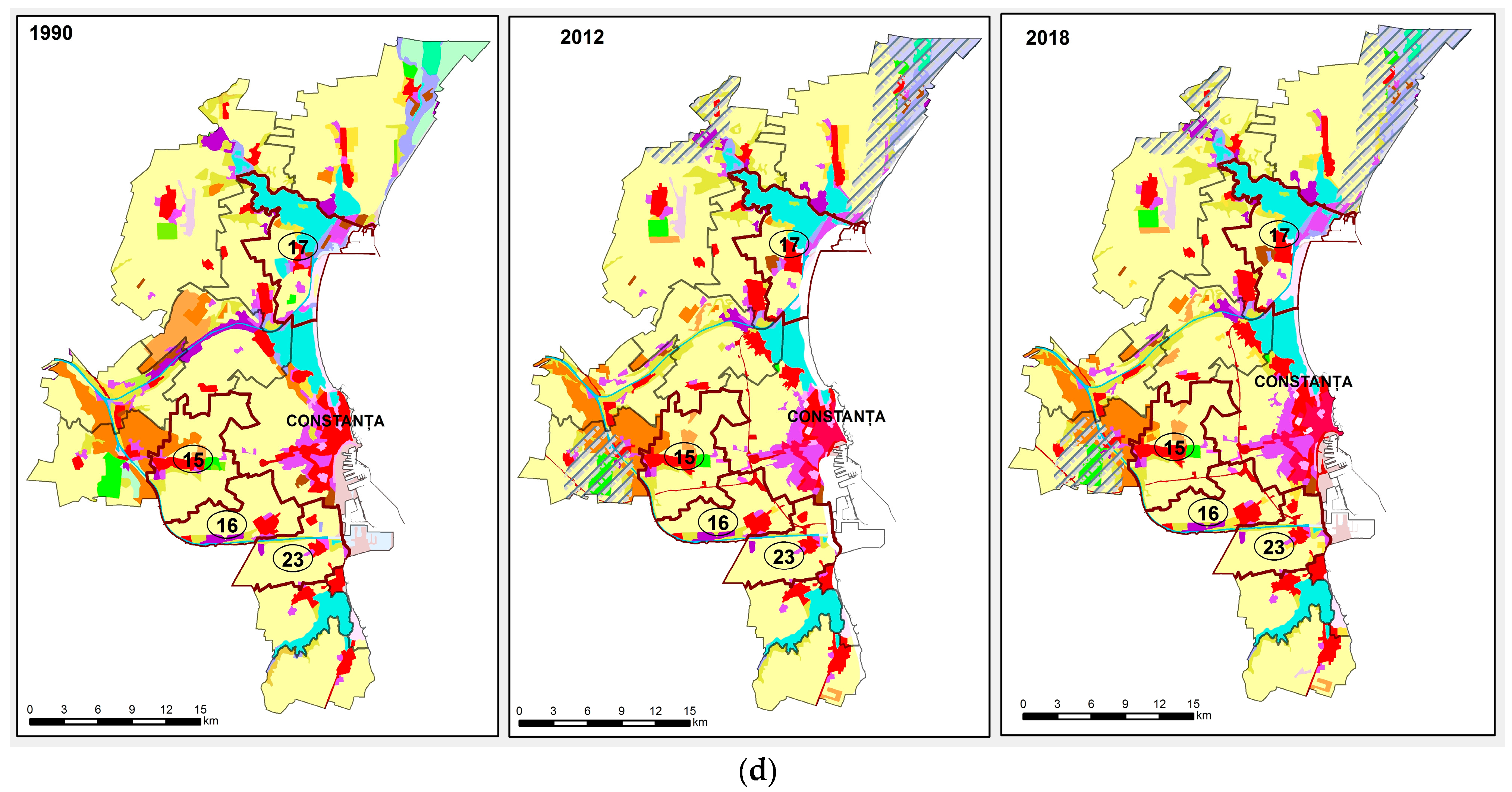

3.3.3. The Peri-Urban Crowns of the Regional Metropolises Cluj-Napoca, Timișoara, Iași and Constanța: Similar Dynamics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects. 30 Years of Population Change in Europe (1990–2023). In Pallavi R. Mapped: How Europeʼs Population Has Changed (1990–2023). 2024. Available online: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-how-europes-population-has-changed-1990-2023/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Kurek, S.; Wójłowicz, M.; Gałka, J. The changing role of migration and natural increase in suburban population growth: The case of non-capital post-socialist city (The Krakow Metropolitan Area, Poland). Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2015, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. The Global City; Princeton University Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Tokyo, Japan; Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoș, I. Orașele și organizarea spațiului geografic. Studiu de geografie economic asupra teritoriului României [Towns and the Organization of the Geographical Space. Studies of Economic Geography on Romania’s Territory]; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoş, I. Dinamica Urbană. Aplicaţii la Oraşul şi Sistemul Urban Românesc [Urban Dynamics. Applications on the City and the Romanian Urban System]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics. Recensământul populației și al locuințelor din 21–31 october 2011 [The Population and Housing Census of 21–31 October 2011]. 2012. Available online: http://www.recensamantromania.ro/rpl-2011/rezultate-2011/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- National Institute of Statistics. Recesământul Populației și al Locuințelor. Rezultate Definitive [The Population and housing census. Final Results]. 2022. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-rpl-2021/rezultate-definitive-caracteristici-demografice/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Nelson, A.-C.; Dueker, K.-J. The exurbanization of America and its planning policy implications. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1990, 9, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, A.-X. Exurbanization and Aldo Leopold’s human-land community. In The Planner’s Guide to Natural Resource Conservation; Esparza, A.-X., McPherson, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, R. Internal Migration: Developing Countries. In International Encyclopedia of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.-D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W.-H. Internal migration: What does the future hold? In Internal Migration in the Developed World. Are we becoming less mobile? Champion, T., Coohe, T., Shuttleworth, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, S.-M. Urban policy mobilities, argumentation and the case of the model city. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. New perspectives on ethnic segregation over time and space. A domains approach. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musterd, S.; Marcińzak, S.; van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. The study of the landscape physiognomy of urban areas—The methodology development. Methods Landsc. Res. Diss. Comm. Cult. Landsc. 2008, 8, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Solon, J. Spatial context of urbanization: Landscape pattern and changes between 1950 and 1990 in the Warsaw metropolitan area, Poland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 93, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenster, T. Creative destruction in urban planning procedures: The language of “renewal” and “exploitation”. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenner, F.; Dang, K.-A.; Hölzl, M.; Pedrazzoli, A.; Schmidkunz, M.; Wang, J.; Thierstein, A. Regional Urbanization through Accessibility?—The “Zweite Stammstrecke” Express Rail Project in Munich. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berényi, I. Transformation of the Urban Structure of Budapest. GeoJournal 1994, 32, 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, Z.; Szigeti, C.; Harangozó, G. Assessing the sustainability of urbanization at the sub-national level: The Ecological Footprint and Biocapacity accounts of the Budapest Metropolitan Region, Hungary. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L. Changes in the Internal Spatial Structure of Post-Communist Prague. GeoJurnal 1999, 49, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, W.; Schwedler, H.-U. (Eds.) Urban Planning and Cultural Inclusion. Lessons from Belfast and Berlin; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thierfelder, H.; Kabisch, N. Viewpoint Berlin: Strategic urban development in Berlin—Challenges for future urban green space development. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.; Fetner, C.; Piorr, A.; Nielsen-Thomas, S. Peri-urbanization and multifunctional adaptation of agriculture around Copenhagen. Dan. J. Geogr. 2011, 111, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkina, N.; Zaverskiy, S. Challenges of Strong Concentration in Urbanization: The Case of Moscow in Russia. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romańczyk, K.-M. Krakow—The City profile revisited. Cities 2018, 73, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, A.; Malgorzata, D.; Krupowicz, W. Urbanization Chaos of Suburban Small Cities in Poland: “Tetris Development”. Land 2020, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics. România—Un Secol de Istorie. Date Statistice. [Romania—A Century of History. Statistical Data]; National Institute of Statistics: Bucharest, Romania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Top 30 Countries with the Greatest Projected Population Increase and Decrease Between 2020–2100; FactsMaps: 2021. Available online: https://factsmap.com/countries-greatest-projected-population-increase-decrease-2020-2100/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Copernicus Land Management Service (CLMS). 2024. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Emergency Management Service (CEMS). 2024. Available online: https://human-settlement.emergency.copernicus.eu/copernicus.php#inline-nav-1 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Melchiorri, M.; Kemper, T. Establishing an operational and continuous monitoring of global built-up surfaces with the Copernicus Global Human Settlement Layer. In Proceedings of the Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), Heraklion, Greece, 17–19 May 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. How Green Are European Cities? Green Space Key to Well-Being-But Access Varies. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/highlights/how-green-are-european-cities (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- European Urban Initiative. Greening Cities. 2023. Available online: https://www.urban-initiative.eu/innovative-actions-greening-cities (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- European Commission. Urban Nature Platform. Supporting Towns and Cities in Restoring Nature and Biodiversity. 2024. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/urban-environment/green-city-accord_en (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Romanian Parliament. Legea nr. 351 din 6 iulie 2001 privind aprobarea Planului de amenajare a teritoriului national—Secțiunea a IV-a: Rețeaua de localități [Law no. 351 of July for the approval of the National Territory Planning Scheme, Section IV: Settlement Network]. Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 24 July 2001; p. 408.

- Romanian Parliament. Legea nr. 24 din 15 ianuarie 2007 privind reglementarea și administrarea spațiilor verzi din interiorul localităților [Law No. 24 of 15 January 2007 on the Regulation and Administration of Green Spaces within Localities]. Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 18 January 2007; p. 36.

- Romanian Parliament. Lege nr. 313 din 12 octombrie 2009 pentru modificarea și completarea Legii nr. 24/2007 privind reglementarea și administrarea spațiilor verzi din zonele urbane [Law No. 313 of 12 October 2009 Aamending and supplementing Law No. 24/2007 on the Regulation and Management of Green Spaces in Urban Areas]. Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 15 October 2009; p. 694.

- Romanian Parliament, Legea nr. 135 din 15 oct. 2014 pentru modificarea alin. (5) al art. 21 din Legea nr. 10/2001 privind regimul juridic al unor immobile preluate abuziv în perioada 6 martie 1945—22 decembrie 1989, precum și pentru completarea art. 18 din Legea nr. 24/2007 privind reglementarea și administrarea spațiilor verzi din interiorul localităților [Law no. 135 of 15 October 2014 amending paragraph (5) of art. 21 of Law no. 10/2001 on the Legal Regime of Properties Taken Over Abusively between 6 March 1945 and 22 December 1989, as well as supplementing art. 18 of Law no. 24/2007 on the Regulation and Administration of Green Spaces within Localities]. Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 16 October 2014; p. 753.

- Romanian Government, Ordonanță de urgență nr. 195 din 22 decembrie 2005 privind protecția mediului [Emergency Ordinance No. 195 of December 22, 2005 on Environmental Protection], Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 30 December 2005; p. 196.

- Romanian Government, Ministerul Dezvoltării, Lucrărilor Publice și Locuințelor, Ordinul nr. 1 549/2008 privind aprobarea Normelor tehnice pentru elaborarea Registrului local al spațiilor verzi [Order No. 1 549/2008 on the Approval of the Technical Norms for the Development of the Local Register of Green Spaces]. Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 10 December 2008; p. 829.

- Romanian Parliament, Legea nr. 246 din 20 iulie 2022 privind zonele metropolitane, precum și pentru modificarea și completarea unor acte normative [Law No. 246 of 20 July 2022 on Metropolitan Areas, as well as for amending and supplementing certain normative acts]. Monitorul Oficial al României/Official Journal of Romania, 25 July 2022; p. 745.

- Storia.ro Analiză Storia—um au evoluat prețurile apartamentelor în principalele orașe din țară [How Apartment Prices Have Evolved in the Main Cities in the Country]. Available online: https://www.storia.ro/blog/newsroom/stiri/analiza-storia-cum-au-evoluat-preturile-apartamentelor-in-principalele-orase-din-tara-2 (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Imobiliare.ro. Apartamentele noi Continuă să se Scumpească. La Nivel Național, Prețul Apartamentelor Atinge o Nouă Valoare Record [New Apartments Continue to Rise in Price. Nationally, Apartment Prices Reach a New Record high]. June 2024. Available online: https://www.imobiliare.ro/imoexpert/apartamentele-noi-continua-sa-se-scumpeasca-la-nivel-national-pretul-apartamentelor-atinge-o-noua-valoare-record_db/ (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Lipchin, T. Angajații Români Achită Cele Mai Mari Impozite și Taxe. Aproape 43% din Salariul Brut al Unui Angajat din România Ajunge la Bugetul de stat [Romanian Employees Pay the Highest Taxes and Fees. Almost 43% of the Gross Salary of an Employee in Romania Goes to the State Budget]. Available online: https://www.euronews.ro/articole/angajatii-romani-achita-cele-mai-mari-impozite-si-taxe-aproape-43-din-salariul-br (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Mocanu, I. Șomajul din România. Dinamică și diferențieri geografice [Unemployment in Romania. Dynamics and Geographical Differentiation]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, B. Oraşele Monoindustriale din România Între Industrializare Forţată şi Declin Economic, [One-Industry Town in Romania between Forced Industrialization and Economic Decline]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Draghia, M. The peri-urbanisation effect: Emerging functional spatial patterns in Romania. Case-study for 4 major cities: Brașov, Cluj-Napoca, Iași and Timișoara. J. Urban Landsc. Plan. 2021, 6, 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Iordan, I. Zona Peri-Urbană a Bucureştilor [The Peri-Urban Area of Bucharest]; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Erdeli, G.; Cândea, M.; Braghină, C.; Costachie, S.; Zamfir, D. Dicționar de geografie umană [Dictionary of Human Geography]; Corint Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae, I. Suburbanismul ca Fenomen Geografic în România [Suburbanism, as a Geographical Phenomenon in Romania]; Meronia Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neacşu, M.-C. Oraşul sub lupă. Concepte Urbane. Abordare geografică [The City Under the Magnifying Glass. Urban Concepts. Geographic Approach]; Pro-Universitaria Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muntele, I. Urbanisation et countreurbanisation dans lʼEurope dʼaprès-guerre [Urbanisation and counterurbanisation in post-war Europe]. Rev. Roum. De Géographie Rom. J. Geogr. 2009, 53, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, I.; Kucsicsa, G.; Mitrică, B. Assessing spatio-temporal dynamics of urban sprawl in the Bucharest Metropolitan Area over the last century. In Land Use/Cover Changes in Selected Regions in the World; International Geographical Union, Charles University: Prague, Czech Republic, 2015; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nae, M. Geografia Calităţii vieţii Urbane. Metode de Analiză [Geography of Urban Quality of Life. Methods of Analysis]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muja, S. Dezvoltarea Spațiilor Verzi în Sprijinul Conservării Mediului Înconjurător în România [Developing Green Spaces to Support Environmental Conservation in Romania]; Ceres Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Greencommunity.ro; Dinu, C. Cât de Verzi Sunt Șase Dintre Cele Mai Mari Orașe Din România. Studiu Comparative Despre Cum arată Situația Spațiilor Verzi în București, Cluj, Timișoara, Iași, Brașov și Oradea [How Green Are Six of the Largest Cities in Romania? Comparative Study on the Situation of Green Spaces in Bucharest, Cluj, Timisoara, Iași, Brașov and Oradea]. Available online: https://greencommunity.ro/top-orase-verzi-romania-registrul-spatiilor-verzi/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Focuspress.ro. Constanța Rămâne cu o Suprafață de Spațiu Verde pe cap de Locuitor Mai Mică Decât cea Prevăzută de Lege [Constanta Remains with a Green Space Area Per Capita Smaller Than That Required by Law. Available online: https://focuspress.ro/constanta-ramane-cu-o-suprafata-de-spatiu-verde-pe-cap-de-locuitor-mai-mica-decat-cea-prevazuta-de-lege/ (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Greenpeace.org; Tănase, A. Spațiile verzi din București, sub 10 mp/cap de locuitor [Green Spaces in Bucharest, Under 10 m2/capita]. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/romania/articol/4401/spatiile-verzi-din-bucuresti-sub-10mp-cap-de-locuitor/ (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Europa Liberă & România; Benea, I. Cât Spațiu Verde (nu) au Locuitorii Marilor Orașe. Marea Păcăleală de la București [How much green space do residents of big cities (not) have? The great hoax from Bucharest]. Available online: https://romania.europalibera.org/a/c%C3%A2t-spa%C8%9Biu-verde-nu-au-locuitorii-marilor-ora%C8%99e-marea-minciun%C4%83-de-la-bucure%C8%99ti/31259488.html (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Chelcea, L. Bucureştiul Postindustrial. Memorie, Dezindustrializare şi Regenerare Urbană [Post-Industrial Bucharest. Memory, Deindustrialization and Urban Regeneration]; Polirom Publishing House: Iași, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paraschiv, M.; Nazarie, R. Regenerarea urbană a siturilor de tip brownfield. Studiu de caz: Zonele industriale din sectorul III, Municipiul București [Urban regeneration of brownfield land. Case Study: Industrial areas in sector III, Bucharest Municipality]. Analele Asoc. Prof. A Geogr. Din România 2010, 1, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cepoiu, A.-L. Rolul activităților industriale în dezvoltarea așezărilor din spațiul metropolitan al Bucureștilor [The Role of Industrial Activities in the Development of Settlements in the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D. România de suburbie [Suburban Romania]. Available online: https://panorama.ro/romania-de-suburbie-marea-migratie-oras-periferie-recensamant/ (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Iordan, I. Împrejurimile Bucureștilor. Ghid Turistic [The Surroundings of Bucharest. Touristic Guide]; Societatea R Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dordea, D.; Sprînceană, V.; Casapu, I.; Dobrescu, A. Atlasul Regiunii București-Ilfov. Evaluarea Factorilor de Mediu [Atlas of the Bucharest-Ilfov Region. Evaluation of environmental Factors]; National Library of Romania Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pressone.ro; Popa, L. Atunci vs. Acum. Imaginile din Satelit Arată cum au Dispărut Spațiile Verzi din București în Ultimii 20 de ani [Then vs. Now. Satellite Images Show How Green Spaces in Bucharest Have Disappeared in the Last 20 Years]. Available online: https://pressone.ro/atunci-vs-acum-imaginile-din-satelit-arata-cum-au-disparut-spatiile-verzi-din-bucuresti-in-ultimii-20-de-ani (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Financiar, Z.; Vasiliu, A.-E. Pagina verde. Reportaj Ziarul Financiar. O viață între Betoane. Cum a Ajuns Popești-Leordeni să se „sufoce” în Poluare ? „Nu Există Parcuri, cu Excepția Unuia Singur, mic, unde băncile Sunt Insuficiente, iar Dacă Mergi în week-End, nu ai loc să arunci un ac” [A life Among Concrete. How Did Popești-Leordeni End Up “Suffocating” in Pollution? “There are no Parks, Except for One Small One, Where There are not Enough Benches, and if You Go on the Weekend, You Have no Place to Throw a Needle”]. Ziarul Financiar, 12 February 2023. Available online: https://www.zf.ro/economia-verde/pagina-verde-reportaj-zf-viata-intre-betoane-ajuns-popesti-leordeni-21582921 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Cobârzan, R. Brownfield redevelopment in Romania. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 21E, 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marian-Potra, A.-C.; Ișfănescu-Ivan, R.; Ancuța, C.-A.; Pavel, S. Temporary Uses of Urban Brownfields for Creative Activities in a Post-Socialist City. Case-Study: Timișoara, Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S.; Creţan, R.; Ianăş, A.; Satmari, A. The Romanian Post-Socialist City: Urban Renewal and Gentrification; West University Publishing House: Timișoara, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Săgeată, R. Cross-Border Co-operation Euro-regions at the European Union Eastern Border within the Context of Romania’s Accession to the Schengen Area. Georg. Pannonica 2011, 15, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guran-Nica, L. Investiții străine directe și dezvoltatea sistemului de așezări din România [Foreign direct investments and the development of the settlement system in Romania]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hotnews.ro; Ivanov, C. Ce spații verzi poate să piardă Bucureștiul dacă Parlamentul dă liber la Betonarea Spațiilor Verzi Private [What Green Spaces Could Bucharest Lose if Parliament Gives the Green Light to Concreting Private Green Spaces?]. Available online: https://hotnews.ro/ce-spatii-verzi-poate-sa-piarda-bucurestiul-daca-parlamentul-da-liber-la-betonarea-spatiilor-verzi-private-57785 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

| City | Population (Inhabitants) | Population Decline (% in 2021 Compared to 2011) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2021 | ||

| Bucharest * | 1,883,425 | 1,716,983 | −8.9 |

| Cluj-Napoca * | 324,576 | 286,598 | −11.7 |

| Iași * | 290,422 | 271,692 | −6.4 |

| Constanța * | 283,872 | 263,707 | −7.1 |

| Timișoara * | 319,279 | 250,849 | −21.4 |

| Brașov | 253,200 | 237,589 | −6.2 |

| Craiova | 269,506 | 234,140 | −14.1 |

| Galați | 249,432 | 217,851 | −12.7 |

| Oradea | 196,367 | 183,105 | −6.8 |

| Ploiești | 209,945 | 180,539 | −14.0 |

| Brăila | 180,302 | 154,686 | −14.2 |

| Arad | 159,074 | 145,078 | −8.8 |

| Pitești | 155,383 | 141,275 | −9.1 |

| Bacău | 144,307 | 136,102 | −5.7 |

| Constanța * | 17.7 m2/inh. |

| Bucharest * | 23.21 m2/inh. |

| Iași * | 26.15 m2/inh. |

| Oradea | 27.56 m2/inh. |

| Cluj-Napoca * | 28.64 m2/inh. |

| Timișoara * | 41.82 m2/inh. |

| Brașov | 118.54 m2/inh. |

| Name of ATU | Administrative Status | Surface (sqkm) | Number of Component Villages/Localities | Population (inh.) | Demographic Evolution (%) | Number of Homes | Evolution of the Number of Homes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | ||||||

| Chiajna | Commune | 16.1 | 3 | 43,584 | 14,259 | +205.7 | 37,900 | 5916 | +540.6 |

| Bragadiru | Town | 21.79 | 1 | 40,080 | 15,329 | +161.5 | 24,623 | 7696 | +219.9 |

| Popești-Leordeni | Town | 55.8 | 1 | 53,434 | 21,895 | +144.0 | 30,695 | 9520 | +225.8 |

| Berceni | Commune | 24.5 | 1 | 13,766 | 5942 | +131.7 | Md. | Md. | Md. |

| Ștefăneștii de Jos | Commune | 29.0 | 3 | 10,588 | 5775 | +83.3 | 6811 | 2489 | +173.3 |

| Dobroești | Commune | 11.0 | 2 | 16,875 | 9325 | +81.0 | 9745 | 3682 | +164.7 |

| Tunari | Commune | 32.0 | 2 | 9617 | 5336 | +80.2 | 4845 | 1939 | +149.9 |

| Otopeni | Town | 32.0 | 2 | 21,750 | 13,871 | +56.9 | 12,115 | 5930 | +104.3 |

| Corbeanca | Commune | 30.18 | 4 | 11,412 | 7072 | +61.4 | 6031 | 3163 | +90.7 |

| Domnești | Commune | 38.8 | 2 | 12,861 | 8682 | +48.1 | 5730 | 3363 | +70.4 |

| Total peri-urban crown | 7 communes 3 towns | 291.17 | 21 | 233,967 | 107,476 | +117.7 | 138,495 | 43,705 | +216.88 |

| Bucharest | Municipality | 240.0 | - | 1,716,983 | 1,883,425 | −8.8 | 1,038,266 | 844,541 | +22.9 |

| City | Price of New Apartments (Euro/sqm) (September 2024) | Price of New Apartments (September 2023–September 2024) | Price of Old Apartments (Euro/sqm) (September 2024) | Price Evolution of Old Apartments (September 2023–September 2024) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bucharest * | 1833 | +18% | 1942 | +12% |

| Cluj-Napoca * | 2853 | +13% | 2811 | +15% |

| Timișoara * | 1666 | +11% | 1693 | +17% |

| Iași * | 1623 | +13% | 1702 | +21% |

| Constanța * | 1854 | +11% | 1775 | +13% |

| Brașov | 2068 | +7% | 1963 | +20% |

| Craiova | 1695 | +15% | 1654 | +14% |

| Oradea | 1727 | +14% | 1598 | +19% |

| Sibiu | 1554 | +21% | 1742 | +21% |

| Name of ATU | Administrative Status | Surface (km2) | Number of Component Villages/Localities | Population (inh.) | Demographic Evolution (%) | Number of Homes | Evolution of the Number of Homes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | ||||||

| Florești | Commune | 61.0 | 3 | 52,735 | 22,813 | +131.2 | 28,896 | 14,057 | +105.6 |

| Apahida | Commune | 106.0 | 8 | 17,239 | 10,685 | +61.3 | 8142 | 5138 | +58.5 |

| Feleacu | Commune | 48.41 | 5 | 5693 | 3923 | +45.1 | 2492 | 2050 | +21.6 |

| Baciu | Commune | 8.75 | 7 | 13,922 | 10,317 | +34.9 | 6992 | 4426 | +58.0 |

| Gilău | Commune | 116.82 | 3 | 8980 | 8300 | +8.2 | 3975 | 3491 | +13.9 |

| Total peri-urban crown | 5 communes | 340.98 | 26 | 98,569 | 56,038 | +75.9 | 50,497 | 29,162 | +73.16 |

| Cluj-Napoca | Municipality | 179.5 | - | 286,598 | 324,576 | −11.7 | 157,784 | 135,419 | +16.5 |

| Name of ATU | Administrative Status | Surface (sqkm) | Number of Component Villages/Localities | Population (inh.) | Demographic Evolution (%) | Number of Homes | Evolution of the Number of Homes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | ||||||

| Dumbrăvița | Commune | 18.98 | 1 | 20,014 | 7522 | +166.1 | 10,538 | 3064 | +243.9 |

| Giroc | Commune | 55.28 | 2 | 22,270 | 8388 | +165.5 | 13,390 | 3285 | +307.6 |

| Moșnița Nouă | Commune | 66.37 | 5 | 16,424 | 6203 | +164.8 | 6663 | 2337 | +185.1 |

| Ghiroda | Commune | 34.13 | 2 | 8866 | 6200 | +43.0 | 2899 | 2192 | +32.3 |

| Sânmihaiu Român | Commune | 75.26 | 3 | 8419 | 6121 | +37.5 | Md. | Md. | Md. |

| Săcălaz | Commune | 119.49 | 3 | 9223 | 7204 | +28.0 | 3342 | 2786 | +20.0 |

| Total peri-urban crown | 6 communes | 369.51 | 16 | 85,216 | 41,638 | +104.66 | 36,832 | 13,664 | +169.56 |

| Timișoara | Municipality | 130.5 | - | 250,849 | 319,279 | −21.4 | 150,916 | 137,199 | +10.0 |

| Name of ATU | Administrative Status | Surface (sqkm) | Number of Component Villages/Localities | Population (inh.) | Demographic Evolution (%) | Number of Homes | Evolution of the Number of Homes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | ||||||

| Miroslava | Commune | 82,57 | 13 | 28,534 | 11,958 | +138.6 | 14,132 | 4909 | +184.9 |

| Rediu | Commune | 41.6 | 4 | 8295 | 4577 | +81.2 | 4550 | 2063 | +120.6 |

| Ciurea | Commune | 28.76 | 7 | 17,254 | 11,640 | +48.2 | 7847 | 4507 | +74.1 |

| Holboca | Commune | 50.04 | 7 | 13,697 | 11,971 | +14.4 | 5007 | 4562 | +14.4 |

| Tomești | Commune | 37.11 | 4 | 12,169 | 11,051 | +10.1 | 5439 | 4463 | +21.9 |

| Total peri-urban crown | 5 communes | 240.08 | 35 | 79,949 | 51,197 | +56.16 | 36,975 | 20,504 | +80.33 |

| Timișoara | Municipality | 94.0 | - | 271,692 | 290,422 | −6.4 | 152,220 | 122,505 | +24.3 |

| Name of ATU | Administrative Status | Surface (sqkm) | Number of Component Villages/Localities | Population (inh.) | Demographic Evolution (%) | Number of Homes | Evolution of the Number of Homes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2011 | 2021 | 2011 | ||||||

| Năvodari | Town | 70.31 | 2 | 34,398 | 32,981 | +4.3 | 23,755 | 14,073 | +68.8 |

| Valu lui Traian | Commune | 63.29 | 1 | 16,617 | 12,376 | +34.3 | 5869 | 4242 | +38.4 |

| Agigea | Commune | 45.28 | 4 | 8722 | 6992 | +24.7 | 3919 | 2847 | +37.7 |

| Cumpăna | Commune | 50.64 | 2 | 14,757 | 12,333 | +19.7 | 5279 | 4101 | +28.7 |

| Total peri-urban crown | 3 communes 1 town | 229.52 | 9 | 74,494 | 64,682 | +15.17 | 38,822 | 25,263 | +53.67 |

| Constanța | Municipality | 124.89 | - | 263,707 | 283,872 | −7.1 | 136,293 | 123,090 | +10.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Săgeată, R.; Dumitrică, C.; Baroiu, D. Depopulation and the Development of Peri-Urban Green Areas of Large Cities: Lessons Learned from Romania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072925

Săgeată R, Dumitrică C, Baroiu D. Depopulation and the Development of Peri-Urban Green Areas of Large Cities: Lessons Learned from Romania. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072925

Chicago/Turabian StyleSăgeată, Radu, Cristina Dumitrică, and Dragoș Baroiu. 2025. "Depopulation and the Development of Peri-Urban Green Areas of Large Cities: Lessons Learned from Romania" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072925

APA StyleSăgeată, R., Dumitrică, C., & Baroiu, D. (2025). Depopulation and the Development of Peri-Urban Green Areas of Large Cities: Lessons Learned from Romania. Sustainability, 17(7), 2925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072925