Investigating Consumer Attitudes About Game Meat: A Market Segmentation Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

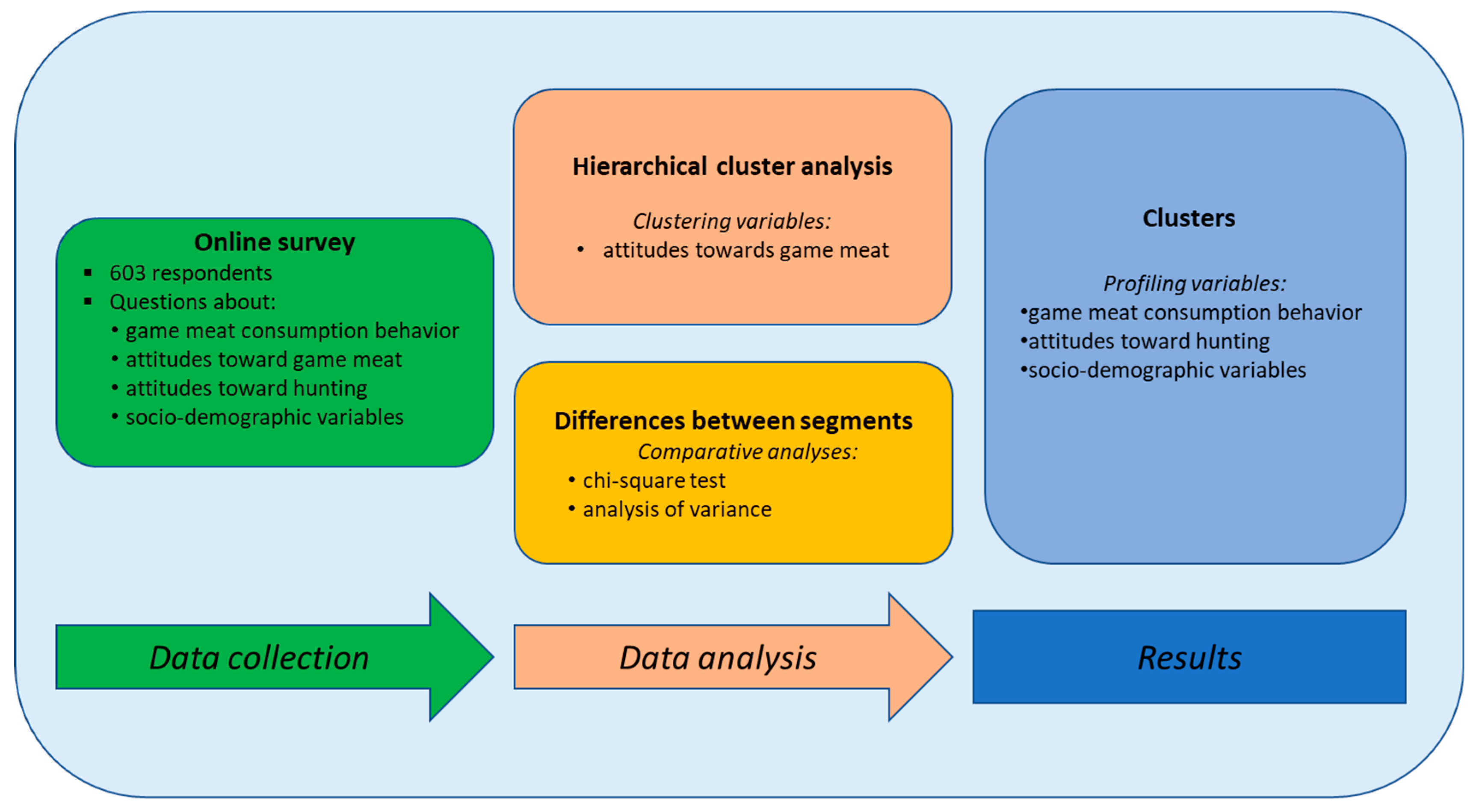

2. Literature Review: Segmentation of Game Meat Consumers

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics and Behavior in Game Meat Consumption

4.2. Consumer Segmentation and Description of Obtained Segments

4.2.1. Cluster 1: Game Meat Lovers

4.2.2. Cluster 2: Occasional Game Meat Consumers

4.2.3. Cluster 3: Game Meat-Averse Consumers

5. Discussion

6. Implications, Conclusions, and Limitations

6.1. Implications

6.2. Conclusions

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sorić, T.; Brodić, I.; Mertens, E.; Sagastume, D.; Dolanc, I.; Jonjić, A.; Delale, E.A.; Mavar, M.; Missoni, S.; Peñalvo, J.L.; et al. Evaluation of the Food Choice Motives before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1232 Adults from Croatia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Stasiak, D.M.; Latoch, A.; Owczarek, T.; Hamulka, J. Consumers’ Perception and Preference for the Consumption of Wild Game Meat among Adults in Poland. Foods 2022, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; McCarl, B.; Fei, C. Climate Change and Livestock Production: A Literature Review. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, K.; Bouhallab, S.; Croguennec, T.; Renard, D.; Lechevalier, V. Recent Trends in Design of Healthier Plant-Based Alternatives: Nutritional Profile, Gastrointestinal Digestion, and Consumer Perception. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 10483–10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denver, S.; Nordström, J.; Christensen, T. Plant-Based Food—Purchasing Intentions, Barriers and Drivers among Different Organic Consumer Groups in Denmark. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Aiking, H. Towards a Reduced Meat Diet: Mindset and Motivation of Young Vegetarians, Low, Medium and High Meat-Eaters. Appetite 2017, 113, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clonan, A.; Wilson, P.; Swift, J.A.; Leibovici, D.G.; Holdsworth, M. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Purchasing Behaviours and Attitudes: Impacts for Human Health, Animal Welfare and Environmental Sustainability. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2446–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer Attitudes towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilar, J.; Kasprzyk, A. Fatty Acids and Nutraceutical Properties of Lipids in Fallow Deer (Dama Dama) Meat Produced in Organic and Conventional Farming Systems. Foods 2021, 10, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, A.; Sánchez-García, C. Nutritional Composition of Game Meat from Wild Species Harvested in Europe. In Meat and Nutrition; Ranabhat, C.L., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marescotti, M.E.; Caputo, V.; Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A. Discovering Market Segments for Hunted Wild Game Meat. Meat Sci. 2019, 149, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowska, M.; Stadnik, J.; Stasiak, D.M.; Wójciak, K.; Lorenzo, J.M. Strategies to Improve the Nutritional Value of Meat Products: Incorporation of Bioactive Compounds, Reduction or Elimination of Harmful Components and Alternative Technologies. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 6142–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, H.D.; Varga, C.; Duquette, J.; Novakofski, J.; Mateus-Pinilla, N.E. Food Safety Considerations Related to the Consumption and Handling of Game Meat in North America. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floris, I.; Vannuccini, A.; Ligotti, C.; Musolino, N.; Romano, A.; Viani, A.; Bianchi, D.M.; Robetto, S.; Decastelli, L. Detection and Characterization of Zoonotic Pathogens in Game Meat Hunted in Northwestern Italy. Animals 2024, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Neves, E.; Abrantes, A.C.; Vieira-Pinto, M.; Müller, A. Wild Game Meat—A Microbiological Safety and Hygiene Challenge? Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2021, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, T.; Bureš, D.; Černý, J.; Hoffman, L.C. Overview of Game Meat Utilisation Challenges and Opportunities: A European Perspective. Meat Sci. 2023, 204, 109284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, M.; Riedl, M.; Šálka, J.; Jarsk, V.; Dobšinská, Z.; Sarvaš, M.; Hustinová, M.; Sarvašová, Z.; Bu, J. Consumer Perceptions and Sustainability Challenges in Game Meat Production and Marketing: A Comparative Study of Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Foods 2025, 14, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Državni Zavod za Statistiku Republike Hrvatske Rezultati Ankete o Potrošnji Kućanstava u 2019. Available online: https://web.dzs.hr/Hrv_Eng/publication/2020/SI-1676.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Tolušić, Z.; Florijančić, T.; Kralik, I.; Sesar, M.; Tolušić, M. Game Meat Market in Eastern Croatia. Poljoprivreda 2006, 12, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, A.; Borghesi, F.; Aradis, A. Lead Ammunition Residues in the Meat of Hunted Woodcock: A Potential Health Risk to Consumers. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 15, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of Sustainable Food Consumers: A Literature Review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, A.; Marescotti, M.E.; Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A. Consumers’ Perceptions and Attitudes toward Hunted Wild Game Meat in the Modern World: A Literature Review. Meat Sci. 2022, 194, 108955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasevic, I.; Novakovic, S.; Solowiej, B.; Zdolec, N.; Skunca, D.; Krocko, M.; Nedomova, S.; Kolaj, R.; Aleksiev, G.; Djekic, I. Consumers’ Perceptions, Attitudes and Perceived Quality of Game Meat in Ten European Countries. Meat Sci. 2018, 142, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantechi, T.; Contini, C.; Scozzafava, G.; Casini, L. Consumer Preferences for Wild Game Meat: Evidence from a Hybrid Choice Model on Wild Boar Meat in Italy. Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Luomala, H.; Lähdesmäki, M.; Viitaharju, L.; Kurki, S. Resenting Hunters but Appreciating the Prey?—Identifying Moose Meat Consumer Segments. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2024, 29, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, E.; Vecchiato, D.; Tempesta, T.; Gaviglio, A.; Viganò, R. Consumer Preferences for Red Deer Meat: A Discrete Choice Analysis Considering Attitudes towards Wild Game Meat and Hunting. Meat Sci. 2018, 146, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marescotti, M.E.; Caputo, V.; Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A. Consumer Preferences for Wild Game Cured Meat Label: Do Attitudes towards Animal Welfare Matter? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempen, E.; Wassenaar, A.; Tobias-Mamina, R. South African Consumer Attitudes Underlying the Choice to Consume Game Meat. Meat Sci. 2023, 201, 109175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölker, S.; von Meyer-Höfer, M.; Spiller, A. Inclusion of Animal Ethics into the Consumer Value-Attitude System Using the Example of Game Meat Consumption. Food Ethics 2019, 3, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomska, K.; Kosicka-Gębska, M.; Gębski, J.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Sułek, M. Perception of the Health Threats Related to the Consumption of Wild Animal Meat—Is Eating Game Risky? Foods 2021, 10, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, P.E.; Riley, S.J.; Heberlein, T.A.; Ericsson, G. Eat Prey and Love: Game-meat Consumption and Attitudes toward Hunting. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2012, 36, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomska, K.; Kosicka-Gebska, M.; Gebski, J.; Gutkowska, K.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Sułek, M. Game Meat Consumption-Conscious Choice or Just a Game? Foods 2020, 9, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, M.; Němec, M.; Jarský, V.; Zahradník, D. Unveiling Game Meat: An Analysis of Marketing Mix and Consumer Preferences for a Forest Ecosystem Product. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1463806. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, F.E.; Castro, F.; Villafuerte, R. Control Hunting of Wild Animals: Health, Money, or Pleasure? Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2017, 63, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevillano Morales, J.; Moreno-Ortega, A.; Amaro Lopez, M.A.; Arenas Casas, A.; Cámara-Martos, F.; Moreno-Rojas, R. Game Meat Consumption by Hunters and Their Relatives: A Probabilistic Approach. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2018, 35, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krokowska-Paluszak, M.; Łukowski, A.; Wierzbicka, A.; Gruchała, A.; Sagan, J.; Skorupski, M. Attitudes towards Hunting in Polish Society and the Related Impacts of Hunting Experience, Socialisation and Social Networks. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2020, 66, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. International Segmentation in the Food Domain: Issues and Approaches. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (%) | Cluster 1 (%) | Cluster 2 (%) | Cluster 3 (%) | p-Chi-Square Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47.9 | 63.6 | 37.3 | 21.9 | <0.01 |

| Female | 52.1 | 36.4 | 62.7 | 78.1 | ||

| Age | 18–35 | 47.4 | 53.1 | 42.2 | 42.5 | >0.05 |

| 36–55 | 45.6 | 41.6 | 49.6 | 47.9 | ||

| >55 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 9.6 | ||

| Place of residence | Urban | 62.2 | 61.9 | 61.1 | 67.1 | >0.05 |

| Rural | 37.8 | 38.1 | 38.9 | 32.9 | ||

| Education | Elementary | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.0 | <0.01 |

| Secondary | 28.5 | 26.2 | 29.9 | 32.9 | ||

| University (bachelor’s or master’s level) | 53.4 | 61.5 | 45.1 | 49.3 | ||

| Postgraduate | 17.1 | 12.2 | 22.5 | 17.8 | ||

| Household monthly income | <EUR 1500 | 27.7 | 25.2 | 29.1 | 32.9 | >0.05 |

| EUR 1501–2500 | 35.0 | 35.7 | 33.6 | 37.0 | ||

| EUR 2501–3500 | 24.7 | 25.5 | 25.4 | 19.2 | ||

| >EUR 3500 | 12.6 | 13.6 | 11.9 | 11.0 | ||

| Employment status | Student | 15.9 | 17.1 | 14.8 | 15.1 | >0.05 |

| Employed | 76.9 | 78.0 | 77.0 | 72.6 | ||

| Unemployed | 4.3 | 2.4 | 5.7 | 6.8 | ||

| Retired | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 5.5 | ||

| Diet | Diverse diet | 98.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 86.3 | <0.05 |

| Vegetarian | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.5 | ||

| Vegan | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | ||

| Pescetarian | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.5 | ||

| Do you hunt? | Yes | 33.3 | 50.7 | 21.7 | 4.1 | <0.01 |

| No | 66.7 | 49.3 | 78.3 | 95.9 | ||

| Are any of your immediate family members hunters? | Yes | 37.1 | 46.2 | 29.9 | 26.0 | <0.01 |

| No | 62.9 | 53.8 | 70.1 | 74.0 | ||

| Are any of your friends hunters? | Yes | 71.6 | 84.6 | 64.3 | 45.2 | <0.01 |

| No | 28.4 | 15.4 | 35.7 | 54.8 |

| Total (%) | Cluster 1 (%) | Cluster 2 (%) | Cluster 3 (%) | p-Chi Square Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you consumed game meat in the last year? | Yes | 80.6 | 95.5 | 80.3 | 23.3 | <0.01 | |

| No | 19.4 | 4.5 | 19.7 | 76.7 | |||

| How often have you consumed game meat in the last year? | I did not consume game meat in the last year | 19.4 | 4.5 | 19.7 | 76.7 | <0.01 | |

| Several times a week | 5.3 | 9.4 | 2.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Once a week | 4.8 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 2.7 | |||

| Several times a month | 15.9 | 24.8 | 9.4 | 2.7 | |||

| Once a month | 9.3 | 12.2 | 8.2 | 1.4 | |||

| Several times a year | 38.1 | 38.5 | 45.9 | 11.0 | |||

| Once in the last year | 7.1 | 2.8 | 12.7 | 5.5 | |||

| What game meat do you consume most often? | Red deer | yes | 36.5 | 51.7 | 26.6 | 9.6 | <0.01 |

| no | 63.5 | 48.3 | 73.4 | 90.4 | |||

| Roe deer | yes | 56.6 | 68.5 | 56.1 | 11.0 | <0.01 | |

| no | 43.4 | 31.5 | 43.9 | 89.0 | |||

| Wild boar | yes | 68.7 | 87.1 | 62.3 | 17.8 | <0.01 | |

| no | 31.3 | 12.9 | 37.7 | 82.2 | |||

| Rabbit | yes | 23.5 | 30.4 | 20.1 | 8.2 | <0.01 | |

| no | 76.5 | 69.6 | 79.9 | 91.8 | |||

| Pheasant | yes | 24.7 | 33.2 | 20.5 | 5.5 | <0.01 | |

| no | 75.3 | 66.8 | 79.5 | 94.5 | |||

| How do you most often consume prepared game meat? | Roasted | yes | 34.3 | 50.7 | 23.4 | 6.8 | <0.01 |

| no | 65.7 | 49.3 | 76.6 | 93.2 | |||

| Stew | yes | 76.9 | 92.0 | 75.8 | 21.9 | <0.01 | |

| no | 23.1 | 8.0 | 24.2 | 78.1 | |||

| Boiled | yes | 13.3 | 20.3 | 8.6 | 1.4 | <0.01 | |

| no | 86.7 | 79.7 | 91.4 | 98.6 | |||

| Pâté | yes | 13.9 | 19.6 | 11.1 | 1.4 | <0.01 | |

| no | 86.1 | 80.4 | 88.9 | 98.6 | |||

| Soup | yes | 20.2 | 28.7 | 15.2 | 4.1 | <0.01 | |

| no | 79.8 | 71.3 | 84.8 | 95.9 | |||

| Cured products | yes | 46.6 | 62.9 | 38.9 | 8.2 | <0.01 | |

| no | 53.4 | 37.1 | 61.1 | 91.8 | |||

| On what occasions do you consume game meat? | With friends/family | yes | 56.7 | 69.2 | 53.7 | 17.8 | <0.01 |

| no | 43.3 | 30.8 | 46.3 | 82.2 | |||

| Celebrations | yes | 45.1 | 56.3 | 41.4 | 13.7 | <0.01 | |

| no | 54.9 | 43.7 | 58.6 | 86.3 | |||

| Business occasion | yes | 14.4 | 19.2 | 12.3 | 2.7 | <0.05 | |

| no | 85.6 | 80.8 | 87.7 | 97.3 | |||

| During hunting activities | yes | 23.5 | 37.8 | 13.1 | 2.7 | <0.01 | |

| no | 76.5 | 62.2 | 86.9 | 97.3 | |||

| Regardless of the occasion | yes | 13.3 | 17.8 | 11.5 | 1.4 | <0.05 | |

| no | 86.7 | 82.2 | 88.5 | 98.6 | |||

| Where do you consume game meat? | In restaurants | yes | 20.7 | 26.2 | 19.3 | 4.1 | <0.01 |

| no | 79.3 | 73.8 | 80.7 | 95.9 | |||

| At home | yes | 64.8 | 83.2 | 57.8 | 16.4 | <0.01 | |

| no | 35.2 | 16.8 | 42.2 | 83.6 | |||

| In hunting associations/communities | yes | 32.0 | 47.6 | 21.3 | 6.8 | <0.01 | |

| no | 68.0 | 52.4 | 78.7 | 93.2 | |||

| With whom do you most often consume game meat? | With family | yes | 70.0 | 83.9 | 68.9 | 19.2 | <0.01 |

| no | 30.0 | 16.1 | 31.1 | 80.8 | |||

| With friends | yes | 59.5 | 74.1 | 54.9 | 17.8 | <0.01 | |

| no | 40.5 | 25.9 | 45.1 | 82.2 | |||

| With hunters | yes | 31.0 | 46.2 | 21.7 | 2.7 | <0.01 | |

| no | 69.0 | 53.8 | 78.3 | 97.3 | |||

| What is the origin of the game meat you consume most often? | Domestic | 98.8 | 98.5 | 99.0 | 100.0 | >0.05 | |

| Foreign | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Total | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | p-ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean * (SD) | Mean * (SD) | Mean * (SD) | Mean * (SD) | ||

| I have a positive attitude towards game meat. | 4.21 (1.05) | 4.91 (0.32) | 3.97 (0.73) | 2.29 (1.05) | <0.01 |

| Game meat has a positive effect on my health. | 3.72 (1.11) | 4.50 (0.77) | 3.28 (0.67) | 2.14 (0.92) | <0.01 |

| I like to eat game meat. | 4.00 (1.22) | 4.86 (0.39) | 3.77 (0.63) | 1.37 (0.51) | <0.01 |

| I like the smell of game meat. | 3.67 (1.22) | 4.56 (0.67) | 3.30 (0.69) | 1.45 (0.65) | <0.01 |

| I like the taste of game meat. | 3.98 (1.20) | 4.84 (0.39) | 3.75 (0.60) | 1.38 (0.52) | <0.01 |

| Game meat is rich in protein. | 4.18 (0.91) | 4.80 (0.46) | 3.75 (0.61) | 3.14 (1.24) | <0.01 |

| Game meat is low in fat. | 3.88 (1.00) | 4.48 (0.78) | 3.47 (0.69) | 2.86 (1.11) | <0.01 |

| Game meat has a favorable content of essential amino acids. | 3.79 (0.97) | 4.38 (0.80) | 3.41 (0.61) | 2.74 (1.01) | <0.01 |

| Game meat is rich in vitamins. | 3.72 (0.98) | 4.35 (0.82) | 3.30 (0.59) | 2.67 (0.93) | <0.01 |

| Total | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | p- ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean * (SD) | Mean * (SD) | Mean * (SD) | Mean * (SD) | ||

| I have a positive attitude about hunting. | 3.55 (1.37) | 4.29 (1.05) | 3.18 (1.17) | 1.93 (1.16) | <0.01 |

| I do not see anything wrong with hunting animals for their meat as long as the animal is not endangered. | 3.80 (1.28) | 4.44 (0.99) | 3.51 (1.02) | 2.25 (1.41) | <0.01 |

| Hunting helps maintain the balance in nature. | 3.92 (1.19) | 4.55 (0.83) | 3.63 (0.97) | 2.41 (1.35) | <0.01 |

| Most hunters are well-prepared when they go hunting. | 3.27 (1.07) | 3.50 (1.10) | 3.14 (0.94) | 2.82 (1.11) | <0.01 |

| Hunters are well-trained and follow hunting regulations. | 3.22 (1.14) | 3.54 (1.14) | 3.09 (0.95) | 2.42 (1.28) | <0.01 |

| Hunting is an important rural tradition. | 3.58 (1.24) | 4.10 (1.17) | 3.38 (0.90) | 2.21 (1.24) | <0.01 |

| I consider any form of sport–recreational hunting to be cruel to animals. (RECOD) | 3.57 (1.36) | 4.03 (1.27) | 3.26 (1.22) | 2.79 (1.55) | <0.01 |

| Hunters often injure animals, which then die a slow and painful death. (RECOD) | 3.55 (1.11) | 3.80 (1.17) | 3.41 (0.95) | 3.08 (1.18) | <0.01 |

| Hunters often ignore safety rules. (RECOD) | 3.40 (1.12) | 3.65 (1.18) | 3.24 (0.94) | 2.92 (1.24) | <0.01 |

| I don’t like people who hunt animals. (RECOD) | 4.01 (1.12) | 4.43 (1.02) | 3.80 (0.96) | 3.14 (1.31) | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomić Maksan, M.; Gerini, F.; Šprem, N. Investigating Consumer Attitudes About Game Meat: A Market Segmentation Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073147

Tomić Maksan M, Gerini F, Šprem N. Investigating Consumer Attitudes About Game Meat: A Market Segmentation Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073147

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomić Maksan, Marina, Francesca Gerini, and Nikica Šprem. 2025. "Investigating Consumer Attitudes About Game Meat: A Market Segmentation Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073147

APA StyleTomić Maksan, M., Gerini, F., & Šprem, N. (2025). Investigating Consumer Attitudes About Game Meat: A Market Segmentation Approach. Sustainability, 17(7), 3147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073147