1. Introduction

Anthropogenic climate and ecosystem changes are challenging the well-being of all living beings. There is increasing evidence that younger adults are especially threatened by the impact of climate change [

1], with the Gen Z/Millennial groups reporting higher rates of climate-change-related psychological distress than all other age groups. Young adults are still developing coping skills, and have more than twice the rate of anxiety symptoms than older adults [

2]. Their lives will be more impacted by climate change, and in a recent survey of young adults, the majority reported that the future is frightening (76%), and that climate change will impact their future plans (63%) [

3]. Empowering young adults with skills to cope internally and engage externally with a wide range of crises facing human society is essential. While rates of climate anxiety and mental disorders are increasing worldwide with greater awareness of climate crises, there is a growing need to provide training in climate resilience skills, especially for young adults, to face these existential challenges. A recent review showed that climate distress interventions focused on teaching coping skills have improved mental health outcomes in adults [

4]. However, there are no longitudinal quantitative studies of in-person climate resilience training in university students.

1.1. University-Based Climate Resilience Training

Higher education has an important role in educating the youth in climate change science, issues, and strategies for coping. More universities across the world are integrating climate change modules into their curriculum. However, only some of these educational offerings focus on the inner resilience skills that support sustained collective engagement. There is only one course for university students that we are aware of focused on emotional skill training dealing with climate change issues [

5]. Thus, there is need for an evidence-supported climate change educational approach that, in addition to disseminating scientific facts about the changing climate, also highlights the connection between inner psychological resources and the ability for outer climate advocacy.

1.2. Climate Resilience Course Development

Our team at the University of California developed and assessed a new climate resilience course. The goal of the course was to provide contemplative skills training and exposure to concepts from thought leaders that support the cultivation of sustainable emotional resilience and climate engagement. A core assumption of the course was that transformation can arise from small, safe, in-person groups with trusted facilitators who model care and compassion for each person and for planetary health. The learning objectives included:

- (1)

Basic skills to support mental health and reduce existential stress through action, inner resources to cultivate emotional resilience, social connection, emotional well-being—and advocacy skills for initiating and sustaining climate-related actions.

- (2)

Perspective shift and experiential learning to help students see themselves as empowered and capable of working collectively with others towards climate solutions.

This course complements other courses that might include some of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our class does not focus on the specific SDGs, but prepares students psychosocially for engaging in the wide range of jobs that promote the SDGs, such as sustainable businesses and environmental management, which require advocacy skills, persistence in the face of obstacles, and working in a community.

1.3. Theory of Change

Information alone is insufficient to lead to perspective shifts and behavior change. Instead, expanding one’s self-efficacy and mindset was supported by learning from inspirational thought leaders, experiential learning, collective climate action, and nature immersion. These different forms of learning served as the basis for students of varied backgrounds and academic interests to explore reactions to climate change and ideas for climate engagement both individually and collectively. The emphasis was on intrapersonal investigation to support interpersonal dialog and collective climate action.

1.4. Theoretical Underpinnings

The theoretical frameworks that served as a basis for the development of our CR course were Acceptance Commitment Training (ACT) and self-determination theory (SDT). ACT emphasizes the acceptance of reality as it is, the cultivation of psychological flexibility, and values-based committed action in the world. It also includes mindfulness skills to promote emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and expand one’s ability to see the perspective of others. The CR course integrates these ideas as fundamental to facing the ecological crisis in an effective way. SDT consists of three key components: individuals aspiring to control actions and life trajectory (autonomy), to gain mastery and be effective (competence), and to feel connected to others (relatedness); all of these derive from intrinsic (not extrinsic) motivation and support well-being [

6]. Group climate projects can enhance cohesive community, social resilience, and collective learning with classmates and instructors [

7]. Identifying and transforming grief and despair involves understanding that we experience challenging emotions about the evolving climate crisis because we love and care deeply about living beings, ecosystems, and the earth [

8].

1.5. Linking CR Course Components to Primary Outcomes

We expect that learning about the range of methods and viewpoints discussed by the wide array of speakers would both promote perspective shifts and inspire group climate projects. The small group discussions and exercises sharing emotions and views in each class may decrease loneliness and increase collective self-efficacy. The experiential exercises included, for example, Joanna Macy’s prompt to “Write a letter to the planet, acknowledging the devastation, expressing your sorrow, and simultaneously finding strength and hope in the interconnectedness of all life, and outlining the actions you will take to heal and regenerate the world around you.”. A range of contemplative practices (a variety of mindfulness, compassion, expressing emotions, interconnection, and nature meditations) may promote improvements in mental health, climate distress, and self-efficacy. Being in a psychologically safe class environment with fellow students may support the emotional processing of climate-related fear, dread and anger, and thereby enhance emotional coping and distress tolerance. The nature immersion experience may enhance connectedness to nature. The group climate project provided an experience of communal action and may reduce loneliness and increase belonging and collective self-efficacy for change.

1.6. The Current Study

For primary outcomes, we expected significant decreases from pre- to post-CR course in climate distress, climate anxiety-related cognitive and functional impairment, depression, anxiety, and stress (Hypothesis 1: climate-related psychological functioning), along with significant increases in individual and collective self-efficacy (Hypothesis 2: climate self-confidence). For secondary outcomes, we also expected improvements in climate engagement, nature connectedness, hope and hopelessness, and loneliness and belonging.

In an exploratory analysis of a subset of participants, we examined whether CR course-related improvements were sustained (i.e., no significant decrease) in the primary outcome variables from post CR course to the 5 months follow-up assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

The study registration was: As Predicted, 185353, Wharton Credibility Lab, University of Pennsylvania.

2.1. Participant Recruitment

Students were informed of the CR course via listservs, newspaper articles, papers, online course announcements, academic advisors, and word of mouth. There were no exclusion criteria. Approximately 190 students enrolled in the 10-week climate resilience elective course during the 2024 Spring quarter at 8 University of California (UC) campuses. Informed consent was obtained from all students who chose to participate in the study, which was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of UC San Diego (#180140; approved 11 January 2024). Students completed self-report measures at baseline, post course, and 5-month follow-up online via Qualtrics with a unique identification number.

2.2. Climate Resilience Course

The 10 in-person weekly classes were taught by university faculty and experienced meditation instructors at each of the 8 UC campuses. Each class consisted of contemplative practices and teachings (30 min), group discussions about pre-class video interviews with experts (20 min), short experiential activities to reinforce the focus of each class (30 min), and planning for the group climate projects (20 min). Exact timing and sequence varied by campus. At least one class was held outside as a nature immersion experience. The final two classes consisted of student presentations of group climate projects.

The role of teachers was to learn and embody personal skills of mindfulness, compassion, and psychological flexibility. Teachers were trained to provide a highly supportive class environment in which students shared personal reactions to didactic information (i.e., videotaped interviews with international climate action leaders), relevance to their lives, and practiced supportive dialog. We developed a cohesive group of expert facilitators who supported one another and provided training in the skills necessary for the course, including group facilitation for highly sensitive topics. In keeping with this aim, we organized twelve teacher support and development meetings before and during the course. The UC faculty were seasoned instructors and the meditation instructors were mindfulness certified, with many years of teaching experience.

2.3. Primary Outcome Measures

To measure climate distress, we used the

Climate Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (C-AAQ) [

9], a one-factor measure of climate distress based on the AAQ-II [

10]. The C-AAQ consists of 6 items scored on a 5-point scale from Never to Very Often, with higher scores indicating maladaptive emotion regulation about the climate, greater adverse avoidance, and distress about negative thoughts and feelings. The C-AAQ has been associated with generalized anxiety [

9]. Internal reliability was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88).

To measure climate-related impairment, we used two subscales of the

Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS) [

11]: eight items measuring

cognitive impairment (trouble concentrating, nightmares, self-criticism, and isolation), and five items measuring

functional impairment (challenges meeting the needs and expectations of family, friends, and work) during the last month (CCAS). The CCAS consists of a 5-point response scale from Never to Almost Always, with higher mean scores indicating greater impairment. Reliability was good (alpha = 0.90).

We measured four facets of climate self-efficacy on a 5-point scale from “Not at all” to “Extremely confident” in one’s belief in one’s ability to work with others collectively to impact a climate change issue, that collective action can impact government policy, that local changes can effect global changes, and that one can cope with strong climate change emotions. Reliability was adequate (alpha = 0.79).

To measure mental health, we used the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) [

12,

13]. The DASS is scored by summing the 7 items per subscale with higher scores indicating greater mental distress. Reliability was excellent (alpha = 0.94).

2.4. Secondary Outcome Measures

To measure secondary outcomes, we used single or several items, adapted from standardized scales when possible to examine changes in willingness to invest time and resources to benefit the environment [

14]; nature connectedness (4 items), adapted from the Connectedness to Nature Scale [

15] and the Nature Relatedness Scale [

16]; climate hope and hopelessness (5 items) [

17] and climate loneliness and climate community belonging (4 items); and personal and climate action questions, such as ‘How many hours per week do you spend on any activity related to climate action?’ (3 items) [

18].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used repeated-measures GLM to test pre- to post-course changes for all outcomes. To correct for multiple comparisons, we applied a Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.0125 (0.05/4) for the four primary outcome variables. Effect sizes were reported using the corrected Hedges’ g, which uses the sample standard deviation of the mean difference adjusted by the correlation between measures plus a correction factor.

We used paired t-tests to examine post course to 5-month follow-up maintenance of CR-course-related improvements in the primary outcome variables.

2.6. Qualitative Data

We conducted brief semi-structured course evaluation interviews one month post course completion, administered by phone by the research study staff of 11 students representing most of the 8 campuses. The interviews included five questions regarding the overall impact of the course on well-being and what activities supported this.

We applied a simple thematic analysis to identify patterns within the responses and create themes to facilitate the interpretation of the data and its meaning [

19]. Thematic analysis works well for understanding experiences, thoughts, and behaviors, such as the responses from these interviews. It pairs well with an explanatory approach to quantitative survey data, which explains the ‘why’ of survey responses [

20]. Two team members read the transcripts separately and generated an initial set of themes condensed into 6 primary themes. With the larger study team, the themes were assessed for redundancy and then condensed into 4 primary themes. The 4 primary themes were applied and cross-checked for inter-rater reliability across all transcripts. Importantly, inter-rater reliability was established at 80% agreement on the codes applied to a purposive sample of the qualitative data.

2.7. Potential Confounding Effect of Campus Political Protests on Outcomes

During the 2024 Spring quarter, campus protests of the ongoing military intervention in Gaza caused upheaval to varying degrees on most UC campuses. This is an important factor, as levels of distress among students, staff, and faculty increased significantly as the protests escalated during Spring 2024. To assess the distress caused by the protests, we asked students the following self-report questions at the post course assessment: “We realize that this has been a tumultuous quarter for many campuses, with disruptions to your classes for some campuses. Has the campus climate this quarter (e.g., campus protests, campus actions) in any way negatively affected your well-being or mental health?” on a Likert scale from 1, not at all, to 4, extreme. We also assessed the overall impact by asking whether “The campus climate affected me mostly in negative ways (felt alone, anxious, angry, etc.)” or “The campus climate affected me mostly in positive ways (felt connected, purpose)”.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Approximately 79% (150 of 190) of participants completed the baseline survey across the eight UC campuses. As shown in

Table 1, the participants were primarily female (71%), Asian (39.6%), White (22.1%), Hispanic (19.5%), undergraduates (72.3%), in good or excellent health (93.1%), and young adults (mean age = 23.2, standard deviation = 8.5) years of age.

3.2. Effect of the CR Course on Primary Outcomes

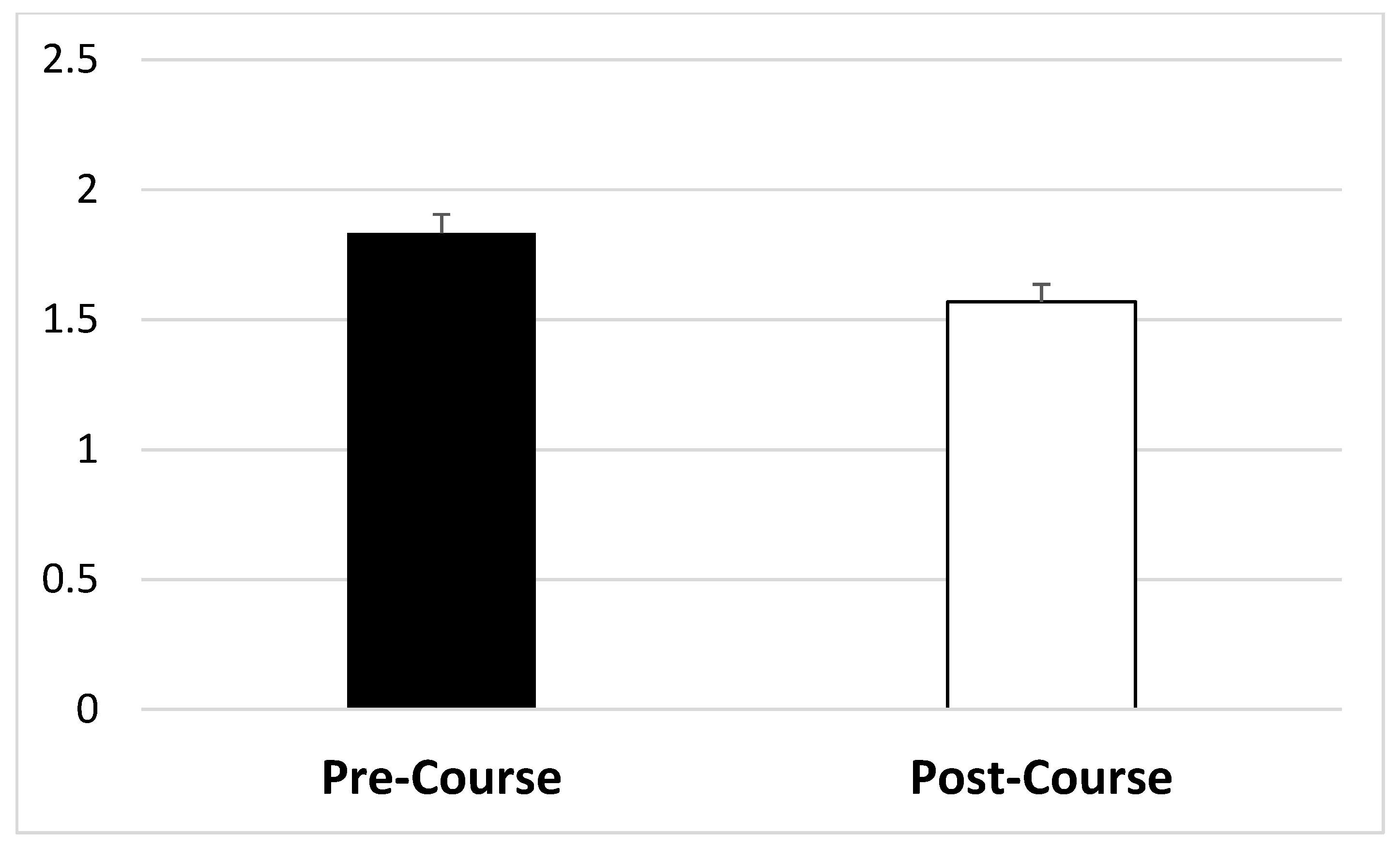

With respect to Hypothesis 1 (climate-related psychological functioning), as shown in

Table 2, we found significant decreases in

climate distress (See

Figure 1) from pre to post CR course, but no changes in climate-related cognitive impairment and functional impairment. For mental health specifically, there were significant decreases in

anxiety, stress, and

depression symptoms, with similar effect sizes for anxiety and depression, but after Bonferroni correction, the decreases in depression were not significant.

For Hypothesis 2 (climate self-confidence), we observed significant increases in individual self-efficacy in coping with strong climate change emotions and collective self-efficacy in one’s ability to work with others collectively to impact a local climate change issue. Two other self-efficacy items, “collective action can impact government policy” and “local changes can effect global changes”, did not meet the corrected p < 0.0125 criterion.

Gender effects: Including male vs. female as a covariate in the above analyses revealed no moderation by gender for any of the primary outcomes, all ts < 1.85, ps > 0.17.

Associations: Given that climate distress can impact mental health generally, we conducted correlation analyses between pre- and post-course changes in climate distress and other outcomes. These analyses found that decreases in climate distress were associated with increases in self-efficacy in coping with climate emotions, r(118) =−0.27, p = 0.003, and decreases in climate-anxiety-related impairment (cognitive, r(119) = 0.36, p < 0.001 and functional, r(119) =0.26, p = 0.005), and depressive symptoms, r(114) = 0.23, p = 0.013.

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

As shown in

Table 3, we found significant increases in nature connectedness, climate community belonging, awareness-raising activity, altruistic intention to change behavior, and decreases in loneliness, hopelessness about the future, the belief that humanity will make the necessary changes to prevent catastrophic climate change, and the belief that humanity is doomed because of climate change. There was a non-significant decrease in hope for humanity.

3.4. Qualitative Interview Results

The thematic analysis generated four primary themes (see

Table S1 for sample quotes).

Connection/Belonging describes connecting with other people who feel the same, not feeling alone in climate work or distress.

Mindfulness/Coping describes how the course helped students slow down, get in touch with their feelings, and manage stress.

Climate Self-efficacy describes the experience of feeling supported and empowered to take action, even in small ways, despite the overwhelming reality of climate catastrophe

. Nature Connection describes feeling good in nature, being reminded there is nature all around, and gratitude and appreciation for nature. Overall, these themes mirror and support several of the quantitative findings.

3.5. Effect of Campus Political Climate on Outcomes

Approximately 29% of respondents reported that the campus protests were associated with moderate-to-extreme negative effects on their well-being. There was an association between greater negative effects and increases in pre- to post-course anxiety symptoms, r(114) = 0.25, p = 0.007; there were no other significant associations. For the overall impact of campus protests, 52.8% indicated a negative effect, while 47.2% reported a positive effect.

3.6. Sustained Effects of CR Course on Primary Outcomes at 5 Months Follow-Up

Paired-sample t-tests showed that from post-course to 5 months follow-up, CR-course-related improvements on the primary outcomes (climate anxiety, self-efficacy, and mental health) were sustained (i.e., did not change significantly), with the exception of decreases in self-efficacy for the belief that local changes can effect global changes, t(70) = 2.44, p = 0.017.

4. Discussion

Our study found that a novel 10-week experiential climate resilience (CR) course for young adults in a university setting was associated with significant improvements in climate distress, self-efficacy for climate action, and mental health. Furthermore, most of the improvements post-course were sustained at the 5-month follow-up assessment. Additionally, qualitative interviews provided more evidence to support the quantitative findings. Importantly, CR-course-related decreases in climate distress were associated with increased self-efficacy in coping with climate emotions as well as decreased depressive symptoms, suggesting a potential mechanism for improving psychological functioning in university students. These findings highlight that climate distress is malleable and improvements may be associated with improved psychological functioning in young adults.

Climate distress decreased significantly after the CR course. There was no evidence of improvement in climate change-related cognitive and functional impairment; however, this may have been due to low baseline levels in our students. We may have seen higher levels if this had been soon after exposure to a climate disaster, like the Los Angeles wildfires. In contrast, the climate AAQ measure appeared to be very sensitive to change with training in resilience skills. This may be an important methodological finding that can inform inclusion of measures in future intervention studies in young adults.

Even though the CR course was not focused on modifying general affective symptoms, there was a consistent reduction across symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Given that more students might be willing to attend a CR course in comparison to a mindfulness meditation course or a mental health intervention, it is promising that the CR course improved emotional functioning across types of symptoms.

Given the increasingly poor mental health and climate distress of young adults, it is recommended that emotional resilience skills training linked to climate actions should be more widely adopted in educational settings. The qualitative interviews with students help to describe some of the experiences underlying the quantitative outcomes (

Table S1). As we discuss the results, we share some select quotes from the 11 students interviewed. We share this as illustrative, only as representative of some students.

With respect to the four areas of self-confidence measured, the results showed that the CR course enhanced self-efficacy for individual emotional coping and collective local engagement, but not impact on government policy and global changes. This is not surprising, as public policy efforts usually take years to result in shifts in large-scale targets of change. We speculate that the individual resilience skills training and group climate project may have been tightly linked to the self-efficacy increases. However, a controlled experimental design would be needed to confirm this potential link. Nonetheless, shifting climate self-efficacy is relevant, as a recent cross-sectional study found that general self-efficacy mediated the relationship between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors, and was associated with longitudinal positive mental health in young adults [

21]. Qualitative studies have examined [

22] (e.g., Bartlett et al., 2022) climate self-efficacy, but our study may be the first to quantitatively examine training-related changes in climate self-efficacy in young adults.

Students increased their sense of self-efficacy around climate advocacy in several ways. Students felt greater confidence in raising awareness about climate issues: “Learning how to talk about climate change to people and not make it just have a negative connotation…, I feel like it’s really easy to lose hope and then just become very … down and depressed about it… the way that they (instructors) taught me how to communicate … it’s just been so much more useful … to speak about it to my family…”

Students reported shifts in climate-related world views and feelings of community. For example, one student said, “One of the most useful things about this course was like the mindfulness and the sense of community, and that really brought me a lot of comfort. Just to be among people who … feel the same things that I’m feeling”. Climate hope scores also significantly increased: “… the course was hope giving, in terms of like, oh there’s actually more people than you might think who are really wanting to do something about it, and wanting to go beyond what I might perceive them to be ready to do”. One student recalled hearing a video expert teacher say something that stayed with them: “… no one can save everyone. But everyone can save someone. … I thought, that’s a really nice… small steps forward are like progress”.

Students reported increases in their ability to down-regulate climate emotions such as despair and anxiety. As one student explained, “I also do feel honestly like a sense of kind of despair around, just the lack of actual, tangible change I think that I see…on a governmental and political level. …after this course I definitely still feel that, but I also feel better equipped to…manage my feelings and emotions around it”. Our study found that decreases in climate distress from pre to post CR courses were associated with increases in self-efficacy in coping with difficult climate emotions and decreases in depression and climate-related cognitive and functional impairment.

Students also reported significant increases in feeling connected to nature. Teachers anecdotally reported strong positive reactions to the nature session. As one student said, “I never explored that area of the campus (botanical garden). So I just got to really appreciate what I have around me. Instead of like rushing to class and stressing…I feel like I don’t take in the environment as much. And it was just really great and like eye opening (to spend time in nature)”.

The mindfulness skills that underscored each session provided a universal skill for emotion regulation, but also may have helped students to embrace a more empowered view of their potential role in change. Indeed, students echoed the theme from the class content that their inner world is connected to their actions (Learning Objective #1): “…if you are more connected to yourself, to the environment… other people, nature, the planet…it’s so real, it’s super powerful that if you are more connected, then you act more in coherence.” “…I’m taking care of myself, and I’m contributing to climate change…not ‘I’m just doing something for myself’-- I’m doing something that …is also a way to contribute(to climate change)…”

Limitations

This CR course development and evaluation showed a promising set of improvements. However, the biggest limitation is that we lacked a control group in this initial test of the intervention. In future iterations, we will test the CR course against a control group course that does not have any experiential psychosocial training. Because of small sample sizes, we were not able to compare how the class might have differed across the 8 campuses. However, all teachers followed the same detailed curriculum and met each week by video conference across campuses to prepare the upcoming sessions and debrief about the past session.

Future challenges include the ability to adapt the course to different student and non-student populations. Teachers could ideally adapt the class to emphasize in depth the specific climate challenges of various regions or for specific vulnerable populations. For example, one of our faculty members in this new year is teaching a modified version of the course by adapting it to how climate change is impacting Black communities. The course, when taught in different regions, would need to be adapted to different cultural contexts, taking into account norms and values that may promote or detract from the values and motivations for planetary stewardship.

The addition of mindfulness teachers to each class required outside financial support not typical in an academic course for credit. The training of faculty members in mindfulness could be a valuable long-term investment, and needed given the ongoing crisis. Alternatively, the course could potentially be taught in resource-poor environments with the appropriate support of a remote mindfulness teacher, such as using videos of mindfulness instruction or a live mindfulness coach who guides the class remotely. We hope to collaborate with and support other institutions to test such modifications in future extensions of the course.

Another limitation is our measurement battery. To keep the survey short, we used single or few items for secondary outcomes. Further, we could not fully evaluate the impact of the campus protests, and would benefit from a more detailed assessment than our single-item assessment.