1. Introduction

Promoting green behavior has become one of the most essential strategies in business organizations, regardless of their size, location, nature of work, and resources [

1]. For instance, Eccles, et al. [

2] stated that sustainability strategy has now become a necessity rather than a voluntary act. This has turned into reality after the announcement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by the United Nations Assembly in 2015, highlighting seventeen goals for better economic, environmental, and social outcomes [

3]. Therefore, organizations now focus on configuring green behaviors to convince stakeholders to comply with the SDGs [

4]. Organizations use various resources, including tangible ones such as technologies [

5], financial capital [

6], new products [

7] and intangible ones such as intellectual capital, managerial motivation [

8], network ties [

9] and so on to improve green behaviors in various units. Organizations also monitor and evaluate these resources (tangible and intangible) to ensure that they are utilized properly to achieve their goals [

6]. Academia and scholars have paid much attention to determining green behaviors in organizations through various methodological approaches such as quantitative (e.g, [

10,

11,

12]), qualitative [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] and conceptual [

18,

19,

20]. For example, studies provide mixed and fragmented evidence, with some showing that organizations rely on top management support to improve green behaviors [

21,

22,

23], while others deem green behaviors as an ethical responsibility [

24,

25], while many scholars view green behaviors as a response to social pressure [

13,

26,

27,

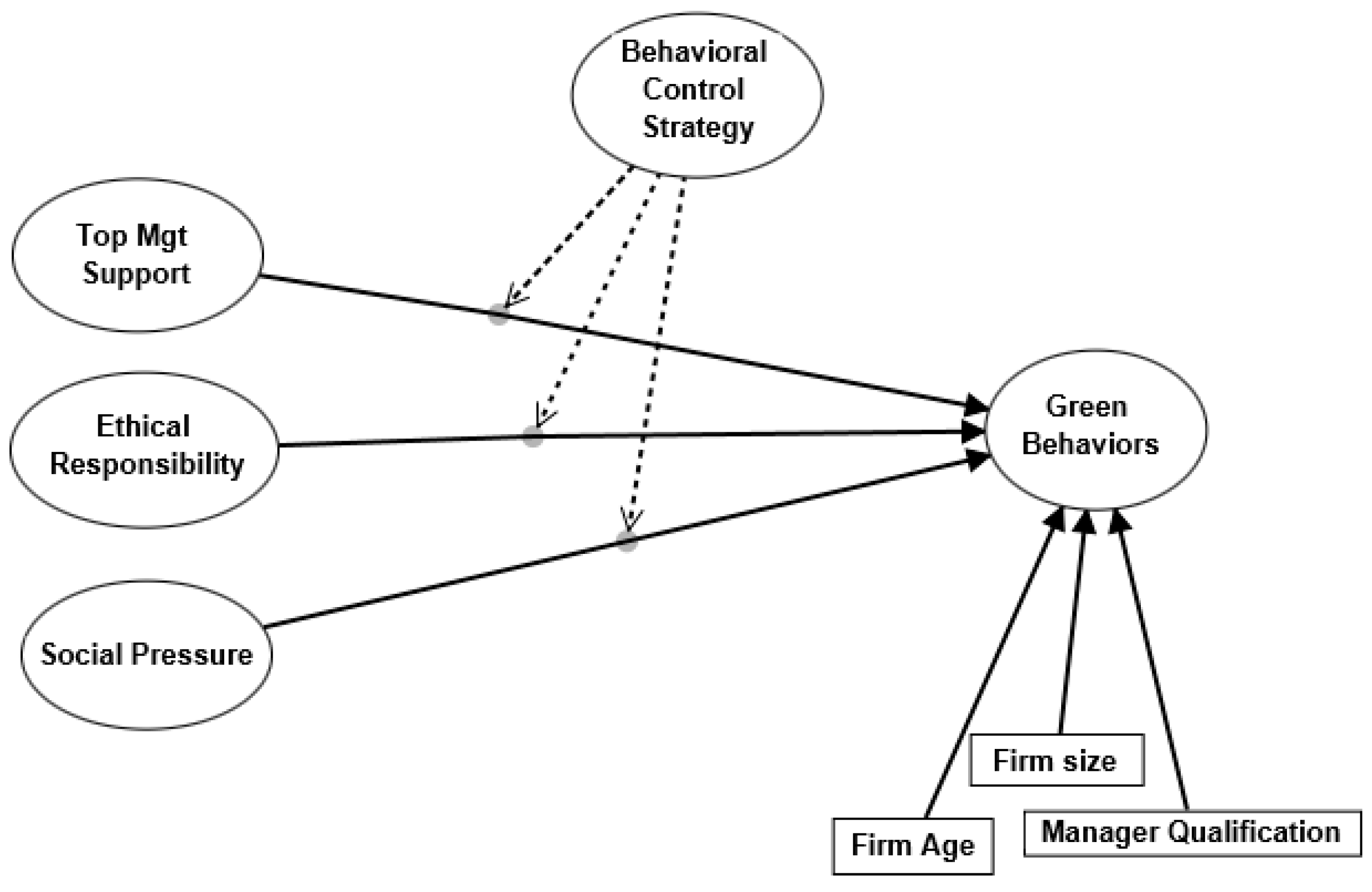

28]. However, one important element missing in this perspective is “behavioral strategic control”. Hence, we fill the gap by examining how organizations with top management support, ethical responsibility, and social pressure improve green behaviors when they implement behavioral strategic control.

Firms in emerging economies such as China have limited resources to configure green and sustainable practices [

29]. For instance, unlike firms located in developed countries such as Europe and the USA, top managers of firms in emerging economies are more geared to motivation, ethics and pressure [

30,

31] as compared to using tangible and intangible resources [

32]. Moreover, regulatory factors and the collectivist culture make motivation, ethics, and social pressure more relevant for the top management team to promote green behaviors in Chinese business industries [

33]. These factors are interrelated as top managers have either motivation, or an adoration for ethical responsibility, or receive pressure to promote green behaviors. While previous studies have focused on other factors or have tested these factors in isolation, we enrich literature by integrating management motivation, ethical responsibility, and social pressure for green behaviors, and how these motives are affected in the presence of behavioral controlling strategies by the governance.

Behavioral Control Strategy (BCS) is essentially driven by Behavior Control Theory, which addresses the behaviors of consumers, employees, or managers toward specific situations [

34]. Behavioral strategic control complements organizational strategies and facilitates managers in aligning their actions with organizational objectives in a controlled manner [

35]. It alerts managers to use resources efficiently (e.g., control) to benefit their organizations [

36].

While some studies claim that BCS can negatively affect green activities in certain contexts and situations. For instance, as pointed out by Onyemah, et al. [

37], excessive and unnecessary behavior controls in organizations divert the focus of top management teams and employees from customers toward supervisors and non-selling tasks. Iqbal, et al. [

38] further stated that authoritarian and excessive control over subordinates led to increased turnover intentions. This suggests that employees are resistant to overly controlling behaviors.

However, BCS can benefit organizations in many ways. For example, they can integrate with middle-level managers to support achieving green behaviors [

39]. They can also focus on ethical responsibility toward green behaviors to align and manage resources and capabilities accordingly [

24]. Having a BCS helps managers deal with social pressure wisely to respond to stakeholders for compliance with green behaviors [

40]. Hence, BCS is deemed one of the most important strategies in today’s era for sustainable activities [

34,

41] Considering the collectivist culture and regulatory strategies in China, recent studies reveal that BCS plays an important role in shaping green activities. For instance, Liu, et al. [

42] demonstrated that BCS motivates young generations toward using green products in China. Zheng, et al. [

43] also demonstrated that BCS is a key parameter of pro-environmental behaviors in China. Khan, et al. [

44] revealed that BCS caused significant improvement in green and sustainable land practices in China. Xie, et al. [

45] concluded BCS has the greatest influence on green activities and sustainable behaviors in China. Hence, these studies provide a strong rationale for the role of BCS in the context of China. While these studies significantly contribute to the literature, it is not yet scrutinized how BCS moderates the path between management motivation, ethical responsibility, social pressure and green behaviors in Chinese business industries. Hence, this research aims to answer the following questions:

Do management motivation, ethical responsibility, and social pressure affect green behaviors in firms?

Does BCS moderate the relationship between management motivation, ethical responsibility, social pressure and green behaviors?

A recent study, by Lim and Weissmann [

34] suggested that a BCS works as a moderator between intentions, behaviors, and organizational outcomes, enriching performance. However, so far, the BCS as a moderator between top management support, ethical responsibility, and social pressures against green behaviors has been overlooked. Hence, this research fills the gap and contributes to the literature on BCS.

This research has two major contributions to literature. First, we fill the gap by examining the moderating role of BCS between top management motivation, ethical responsibility, and social pressure toward green behaviors. While previous studies have broadly tested the direct relationship between top management motivation and green behaviors [

21,

23,

46], ethical responsibility and green behaviors [

24,

47,

48] social pressure and green activities [

27,

49] so far, studies have not assessed how these relationships are moderated by firms employing a BCS. Hence, the insights of this research enrich the literature by adding new information and evidence to the scholarship on BCS. It also facilitates firms located in emerging economies, such as China, to utilize and align their resources properly for green behaviors by implementing a BCS.

Second, this research contributes to the Upper Echelon Theory (UET) and behavioral control theory. By examining managerial factors such as motivation (hereby referred to as management motivation) and ethical responsibility, this study enriches the literature on UET by demonstrating that managers’ attributes and perceptions significantly influence organizational outcomes, such as green behaviors. Unlike previous studies that have emphasized the role of managerial attributes in economic outcomes, this research enriches the literature on UET by focusing on management motivation and ethical responsibility in green behaviors in a collectivist cultural setting. Doing so will enrich the literature by evaluating empirical evidence from Chinese firms. Furthermore, grounded in behavioral control theory, which highlights managerial control behaviors in specific contexts, this research evaluates how BCS moderates the relationships between managerial motivation, ethical responsibility, social pressure, and green behaviors. The insights will contribute to the literature by unleashing positive and negative aspects of the BCS between management motivation, ethical responsibility, social pressure, and green behaviors. Consequently, our research gives policy implications for balancing strategies to configure green behaviors in organizations.

6. Discussion

Empirical findings from the field highlight the roles of top management team in driving green behavior. Prior research has demonstrated that proactive leadership [

82,

139,

154], strong ethical orientations [

155,

156], and stakeholder demands [

4,

108,

124] which critically affects the firm’s sustainable development. Borrowing support from these foundational studies, the current study also illustrates the importance of top management support, ethical responsibility, and social pressure in shaping the organization’s green behavior. Previous research provides a robust understanding of corporate sustainability drivers; however, these characteristics were examined in isolation, without thoroughly examining the role of BCS.

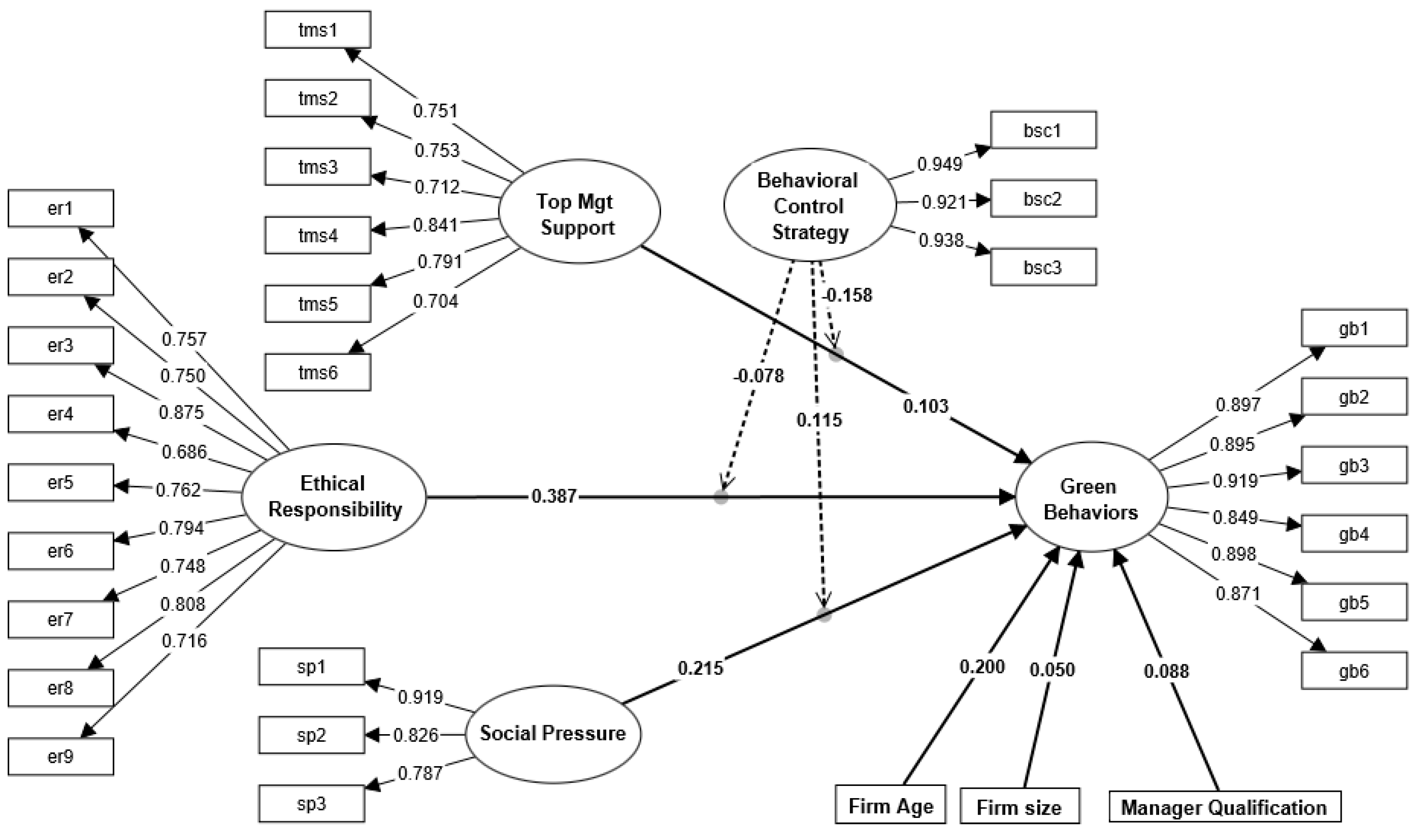

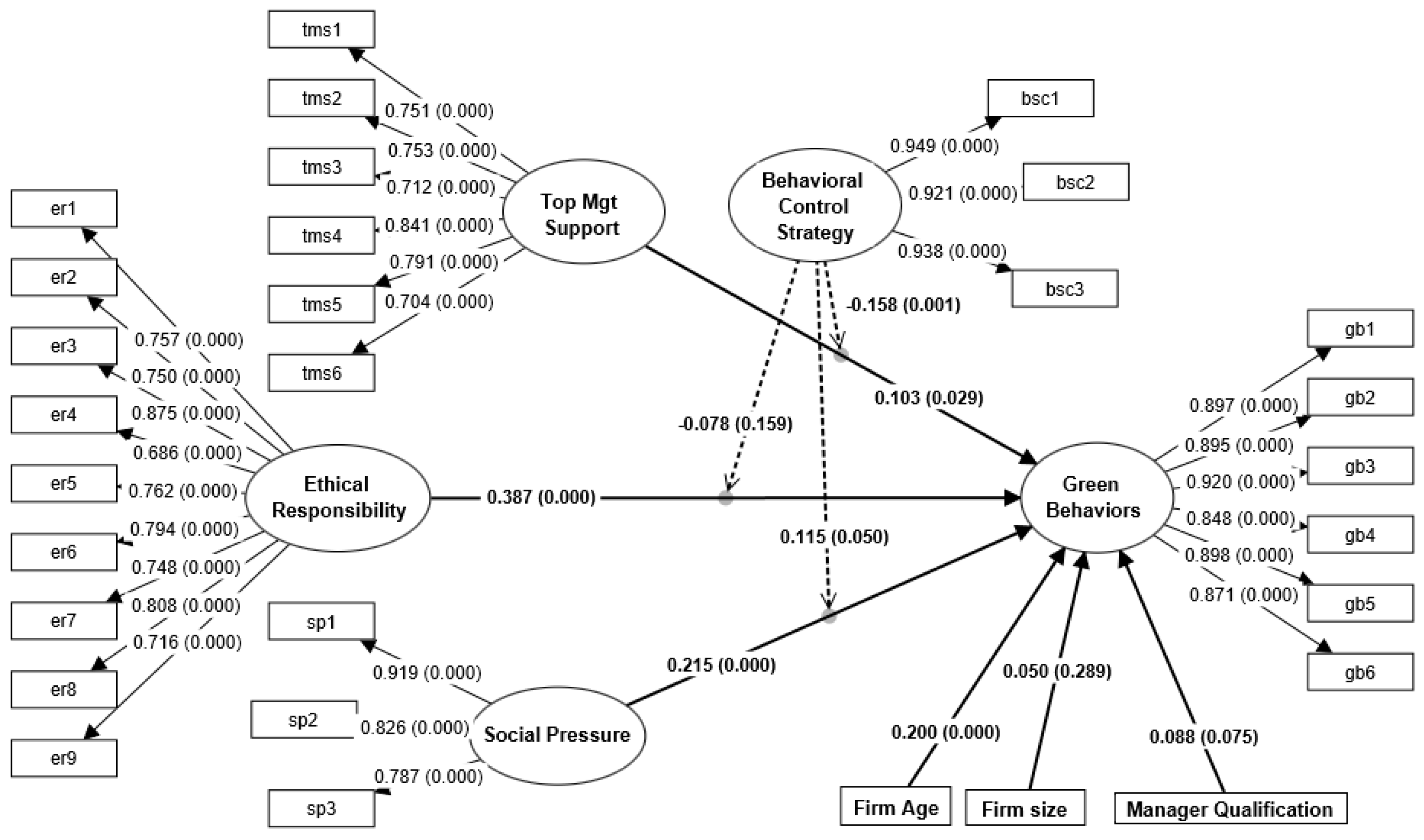

The results revealed that the top management support is significantly related to the firm’s green behavior, hence supporting H1. Consistent with previous research, where Lee, Joo, Lee and Joo [

21] linked top management support with environmental practices, revealing that support by top management, and employees of organizations significantly contribute to sustainable practices. In a similar vein, focusing on Chinese industries, Ye, Cai, Li and Wang [

85] demonstrated that top management commitment is directly related to environmental initiatives which essentially affects the employees ‘green behavior’. Similarly, as pointed out by the UET, top managers are the levers of organizations that direct and manage business activities. Middle managers follow the instructions of the top management team.

The second finding of the current study verifies the positive association between ethical responsibility and a firm’s green behaviors. Ethical responsibility reflects organizational commitment to its moral obligations, specifically its sustainability practices that align with societal expectations [

55]. Organizations with ethical values and responsibility motivate green activities and green behaviors [

24]. Our findings also correspond Choi [

157] who concluded that CEOs with ethical leadership styles have a significant influence on Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB). This corroborates our hypothesis because OCB refers to voluntary behaviors that contribute to an organization’s sustainability [

158]. Businesses located in collective culture, such as China, have high ethical responsibility of doing good for the society [

159,

160]. Hence, managers consider improving green behaviors as one of the key cultural and social responsibilities. They deem that this good action can contribute to their short-term goal (reputation) and long-term goal (sales revenue).

The current study found social pressure a key influencer of organizational green behavior. Our findings align with the existing literature which demonstrates the positive role of external forces in corporate sustainability practices (see, [

27]). Social pressure stems from external bodies such as consumers, regulators, and industry peers, which induces firms to indulge in activities that are eco-friendly and maintain legitimacy and competitive advantage [

58]. Moreover, the findings align with Institutional Theory, which posits that organizations adapt to societal expectations to enhance their legitimacy (see, [

99]). The findings indicate that firms facing strong societal scrutiny mostly integrate environmental sustainability into their core strategies which in turn results in commitment to green behavior [

101,

161]. Our findings corroborate the findings of Leonidou, Christodoulides, Kyrgidou and Palihawadana [

1] which conclude that in the presence of external pressure, firms are more inclined towards sustainable activities and behaviors. Our findings are also in line with to study of Yue, Huo and Ye [

28] which finds coercive pressure as a key determinant of green management in firms. In collective culture such as China, sometime the societies and local communities expect businesses to protect the environment and engage in social activities. If businesses take low participation, these stakeholders push them to perform social practices. Hence, it is considered one of the key dimensions of improving green activities.

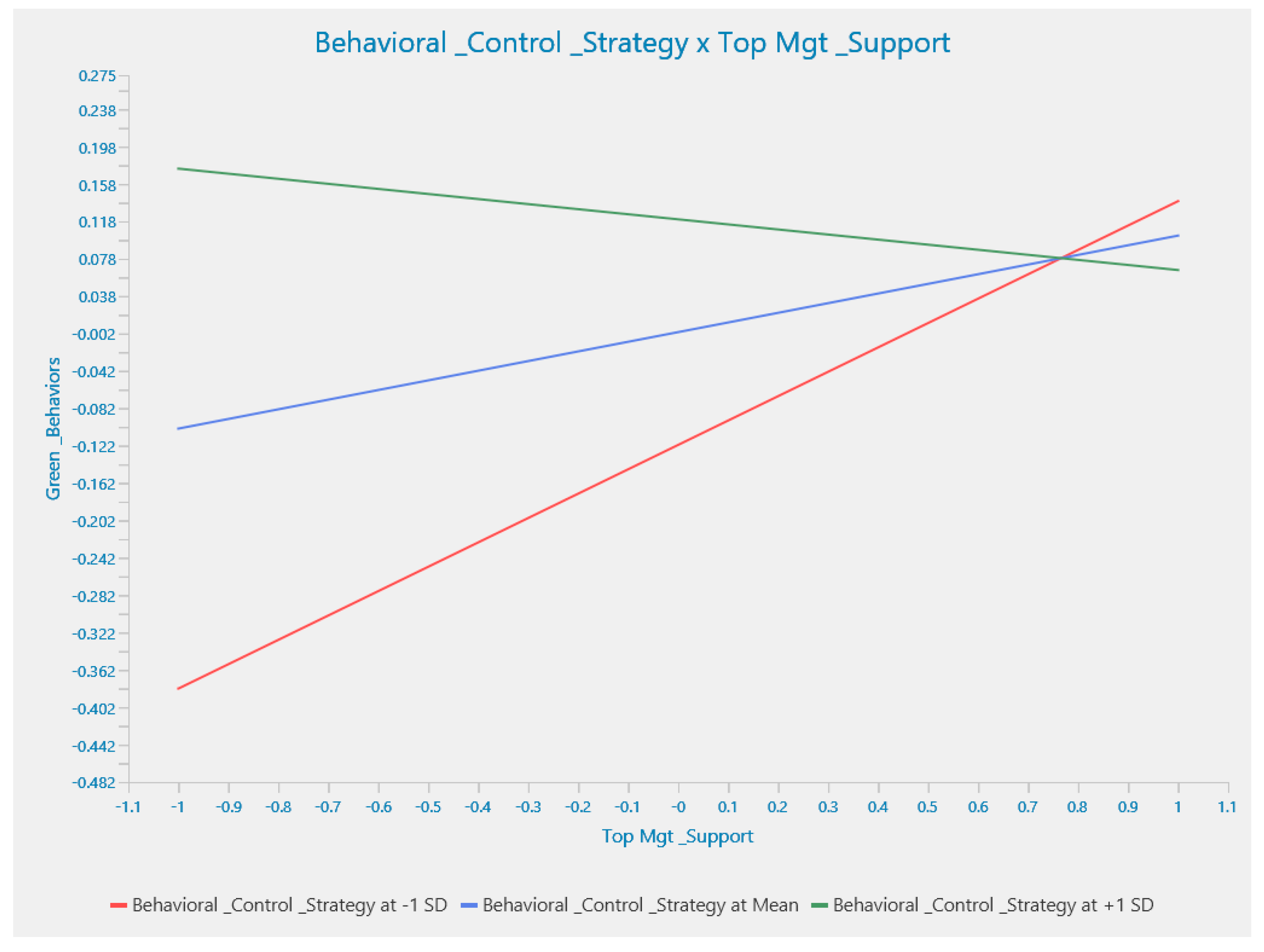

Interestingly, our findings reveal that behavior control strategies played a negative moderating role between top management support and the organization’s green behavior. However, our findings correspond to the negative role of BCS. Consistent with Onyemah, Rouziès and Panagopoulos [

37] who found that excessive behavior controls in firms diverted the focus of employees from customers toward supervisors and non-selling tasks. In a similar context, Iqbal, Asghar and Asghar [

38] investigating Chinese academic institutions revealed that authoritarian and excessive control over subordinates led to increased turnover intentions. This suggests that employees are resistant to overly controlling behaviors. Top managers do not endorse behavioral control as a favorable act when they already support green activities. It illustrates that having an extra control and strategic framework can hamper their role in green activities.

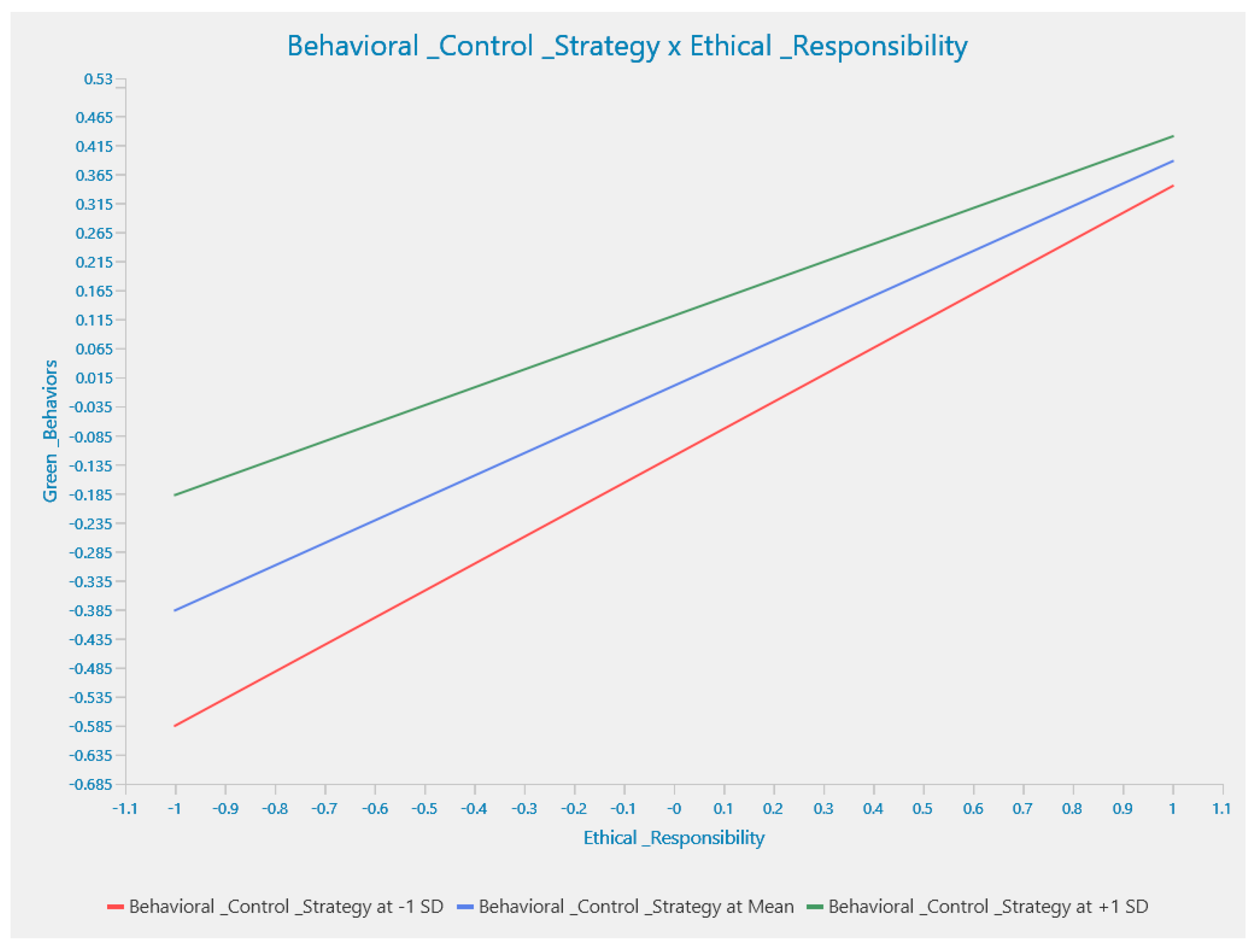

We found that BCS does not play a significant moderating role between ethical responsibilities and green behavior. This is because in hierarchical cultural settings such as China, employees may be more influenced by ethical values and responsibilities rather than the imposed control measures (see, [

33,

162]). If they do and participate in green activities voluntarily, extra control from the shareholders or board of directors can attenuate their role, responsibilities and motivation in green activities. Hence, governance needs to balance BCS for managers to let them perform better activities.

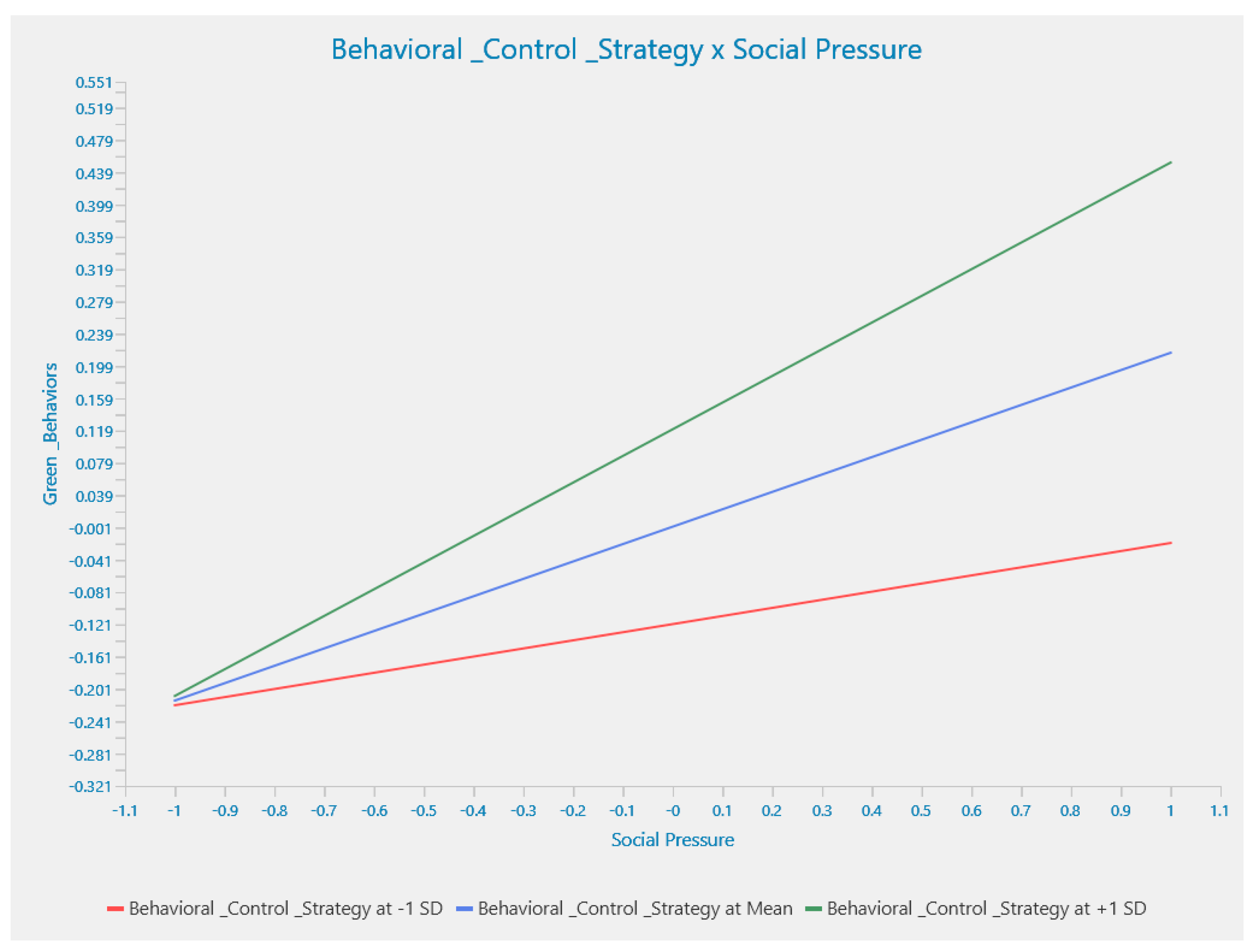

We found that BCS played a significant positive moderating role between social pressure and green behavior, accepting H6. It corresponds to our assumptions that BCS and ethical responsibility work jointly toward sustainable practices [

136]. The findings are in line with the study of Wijethilake and Ekanayake [

139] who found control mechanisms as a key resource for transforming external expectations into desired behaviors. It also validates the findings of Asiaei, Bontis, Barani, Moghaddam and Sidhu [

130] who argued that control mechanisms transform external pressure into green actions. To summarize, in the collectivism culture such as China, managers have strong connection with society and understand their needs, desires and demands, hence, they respect the pressure to perform green activities voluntarily and autonomously.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The current study makes two significant theoretical contributions. Building on this mechanism, the current study enriches the literature by integrating BCS as a moderating variable, consequently highlighting the impact of internal control mechanisms on the relationship between a firm’s green behavior and its determinants. Moreover, the data collection from three different cities in China adds more significance to the literature by enhancing the robustness and generalizability of data, given China’s diverse industrial structure, economic landscapes, and regulatory environments. The current study reinforces the importance of managerial decisions specifically in terms of sustainability and green behavior adoption. While the previous literature has encompassed firm-level sustainability policies, this study encompasses the direct impact of managerial characteristics in fostering green behavior. Moreover, conducting research in three industrial cities in China provides a deep insight into how cultural and institutional contexts affect green behavior, specifically under the influence of behavior control strategies.

Second, the current study extends the understanding of corporate sustainability and green behavior from the lens of UET [

50] and Behavior Control Theory [

34]. For instance, grounded on the UET, our research shows that top management support and responsibility plays an important role in organizational outcomes (green behaviors). These insights add to the literature on the UET in the context of environment and green strategies. This study sheds light on the behavioral aspect of managerial characteristics in green activities and confirms that top management attributes (motivation and responsibility) can improve green behaviors.

Additionally, the negative moderating role of BCS between the relationship of top management support and behavior, while a stronger relationship between social pressure and green behavior in the presence of BCS, challenges traditional conventions of universal effectiveness of control mechanisms. This study adds new insights to the theory on BCS. Although, BCS plays an important role in shaping organizational activities. However, board of governance must understand the balance between managerial responsibility and control system strategy. Previous studies have contributed to the theory on BCS in various context, yet the balance between managerial motivation, responsibility and control strategies has been neglected. Our findings reveal that BCS is not always a positive indicator of organizational activities and there must be balance. For instance, the findings suggest that while social pressure might spur green activity compliances in China, excessive behavior control strategies can undermine the impact of leadership-driven green initiatives by being viewed as micromanagement. The importance of BCS is aligned with the role of situations and real setting and culture. Previous studies have overlooked the importance of cultural setting, managerial motivation and responsibility in conjunction with BCS. Although, these factors are very important to be considered, especially in collectivism cultures such as China. By integrating institutional and cultural dimensions into the discussion, the current study illustrates how social pressure in the presence of BCS translates social pressure into meaningful green behavior rather than symbolic compliance.

6.2. Practical Implications

This research provides valuable insights for corporate governance, top management teams, and practitioners aiming to enhance green behaviors in their organizations and departments.

The positive association between top management support and green behaviors highlights the critical role of leadership in driving sustainable organizational activities. Organizations must allocate sufficient resources and support to their top management teams, enabling them to encourage and guide employees and departments toward green initiatives. Workshops and training on sustainability and ecological practices should be organized to foster a culture of green behaviors throughout the organization.

The positive link between ethical responsibility and green behaviors suggests that ethics, fairness, and accountability within organizations play a significant role in promoting sustainability. Companies should emphasize codes of conduct, moral and social imperatives, and ethical activities to encourage green behaviors. Ethical training, workshops, and reward systems can further reinforce these efforts. Additionally, organizations must avoid practices such as unfair promotions or policies that harm employees, as such actions could undermine the promotion of green behaviors.

Our findings indicate that social pressure significantly influences green behaviors in organizations. Companies should proactively engage stakeholders to understand the demands and expectations of external consumers and customers regarding sustainable practices. Promoting social activities within communities and supporting underserved groups can create a win–win situation, improving green behaviors while contributing to sustainable development.

The negative moderating role of BCS provides a cautionary insight for organizations. It emphasizes the need to ensure that BCS complement, rather than conflict with, the choices and objectives of top management regarding green activities. Leadership should carefully assess whether and when such strategies are necessary. If top management voluntarily supports green behaviors, organizations should create balance between control and their motivation and responsibility. Considering the cultural setting in China, corporate governance should exhibit flexibility and provide support to top management rather than imposing stringent controls, which could negatively impact green behaviors. Alignment and positive communication between top and middle management are essential for enriching green behaviors across the organization.

The insignificant role of BCS in moderating the relationship between ethical responsibility and green behaviors indicates that organizations should focus on their intrinsic ethical values, motivations, and responsibility rather than relying solely on control mechanisms. If BCS are implemented, they should align with internal ethical standards and activities, ensuring they do not become an additional burden or contradict established ethical practices.

Finally, the significant moderating role of BCS between social pressure and green behaviors highlights its importance in addressing external expectations. When external pressures are high, organizations should develop BCS to align their strategic framework with these expectations. This alignment can enhance green behaviors and contribute significantly to sustainable development.

In collectivism culture, such as China, it is important for corporate governance and the board of directors to create balance between managerial motivation, responsibility and control strategies. If managers are highly motivated and perform well in green practices, governance needs to keep lose control strategies. Because having high control and excessive pressure could create adverse results in terms of green behaviors. If managers are highly concerned with green behaviors and understand the social pressure for green and social activities, governance needs to refrain from control strategies. Therefore, the governance body must understand the attributes of managers as well as cultural settings.

Policy makers need to understand the motivation and the ethical responsibility of the managerial teams in industries before implementing control strategies. If they are highly motivated, and perform their activities autonomously, policy makers should avoid implementing additional control strategies, because this can divert their attention from positive to negative one. However, in the case of social pressure, governments and policy makers need to collaborate with industries to fulfill the demands and desire of the external shareholders and communities for green practices.

6.3. Limitations and Future Studies

This research has a few limitations that could be addressed in future studies. First, this study is limited to one country, China, which could lead to geographical limitations. While China is a transition country, it is not a good representative of other emerging and in particular European countries. Hence, future researchers should focus on other countries to enrich the implications of the research. Second, we used cross-sectional data in this study to test the model. While we took care of common method bias, still the issue could affect our results and its implications for practice. Therefore, future researchers should focus on mixed data, interviews, secondary data annual reports, or longitudinal evidence to mitigate common method bias and social desirability bias. Moreover, studies on the determinants of green behaviors have increased in the past decades. Hence, focusing on meta-analyses, systematic and bibliometric could map the research in a better way for future directions. Third, in our model, we tested the moderating role of BCS between top management support, ethical responsibility, social pressure and green behaviors. Future research could consider other factors, such as managerial psychological factors (cognition, personality, and behaviors), and firm-level attributes such as IT resources, financial capital, and culture to understand how certain factors affect green behaviors in the presence of BCS. Our sample has more firms with high-end equipment, which can raise industrial biases. Future researchers should collect equal samples from various industries to enrich the generalizability of the research.

6.4. Conclusions

Green behaviors play a critical role in achieving organizational outcomes such as sustainable development and competitiveness. As a result, organizations have increasingly focused on enhancing green behaviors. In this study, we examined the moderating role of BCS in the relationships between top management support, ethical responsibility, and social pressure toward green behaviors within organizations. Using data from 236 Chinese firms, we tested our hypotheses through a structural model in SmartPLS. The findings reveal that top management support, ethical responsibility, and social pressure significantly improve green behaviors in Chinese organizations. However, contrary to our arguments, we found that BCS negatively moderates the relationship between top management support and green behaviors. Moreover, it does not moderate the relationship between ethical responsibility and green behaviors. Interestingly, BCS significantly strengthens the relationship between social pressure and green behaviors in Chinese organizations. Based on these findings, we contributed to the literature by providing new insights and offered several practical implications for organizational practices.