Exploring Homeowners’ Attitudes and Climate-Smart Renovation Decisions: A Case Study in Kronoberg, Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

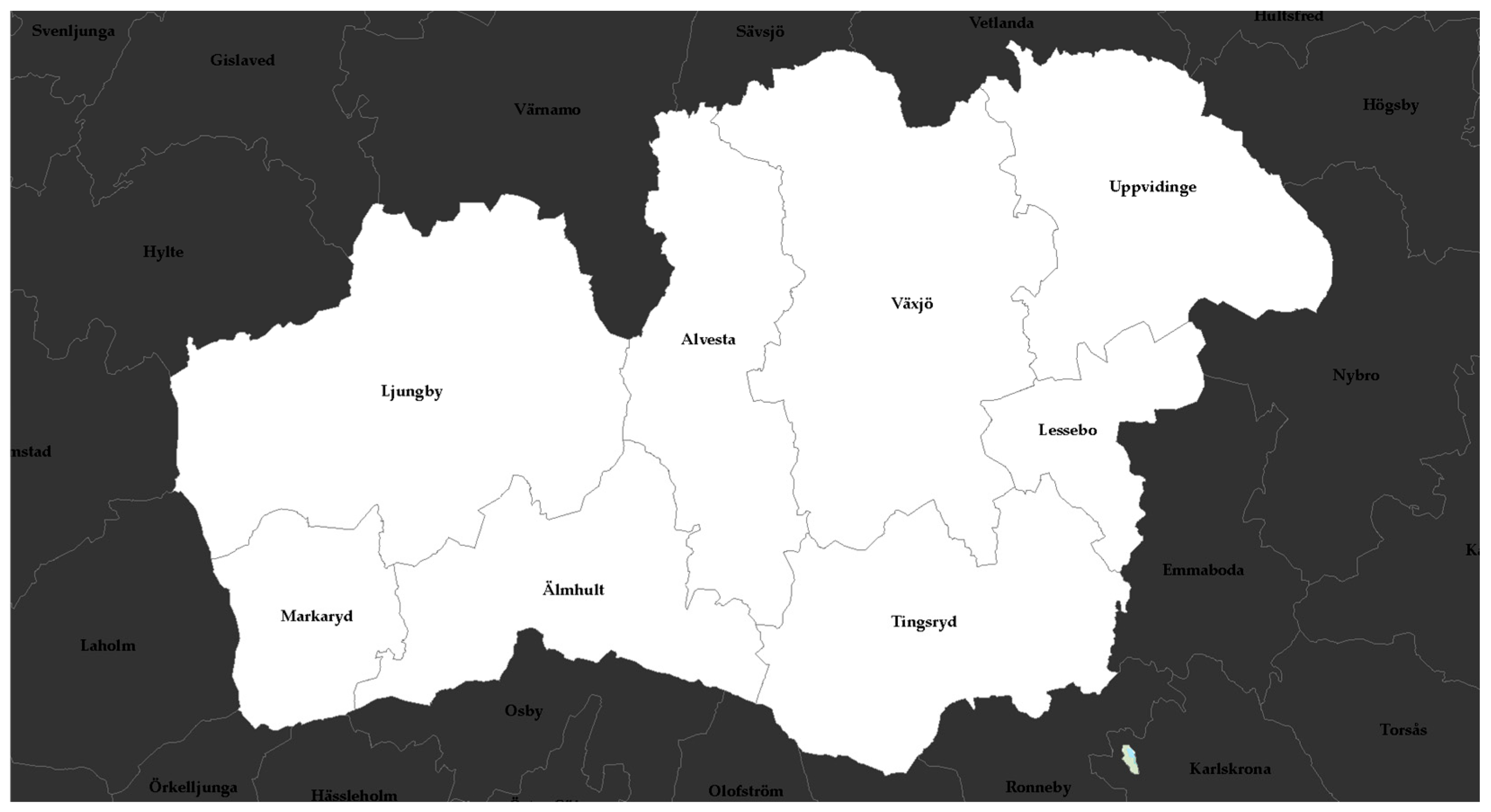

1.2. Context of Study

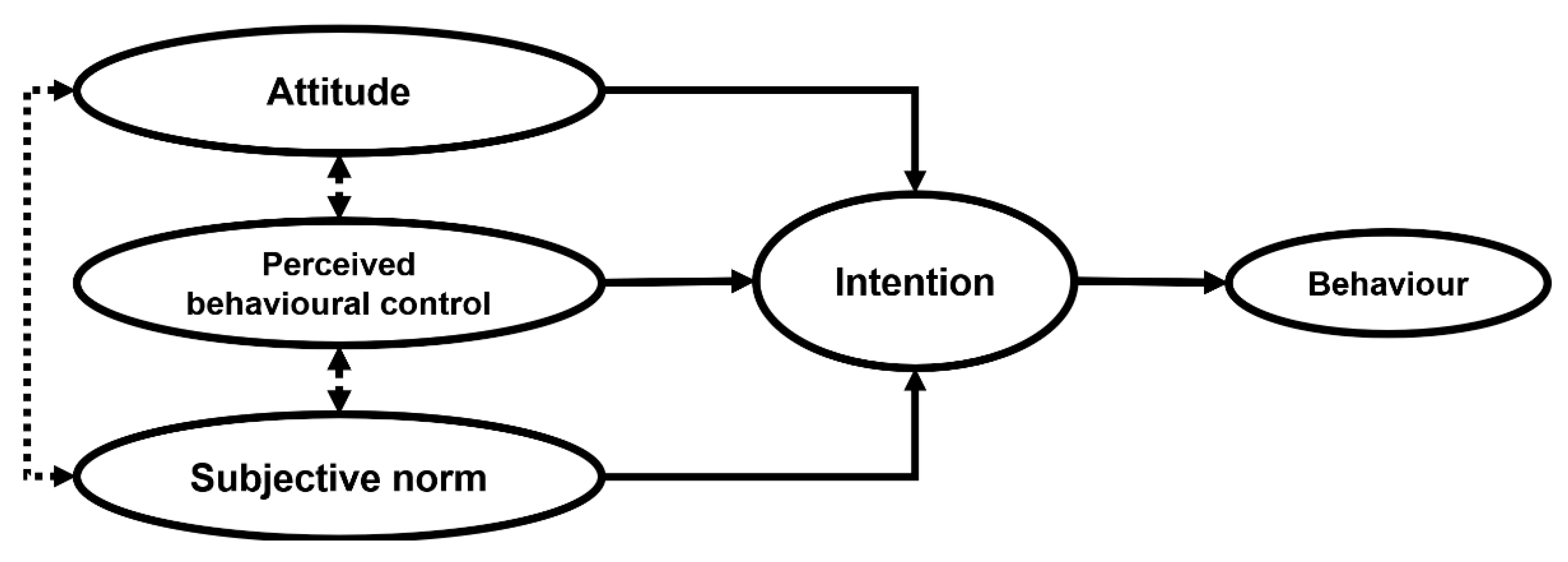

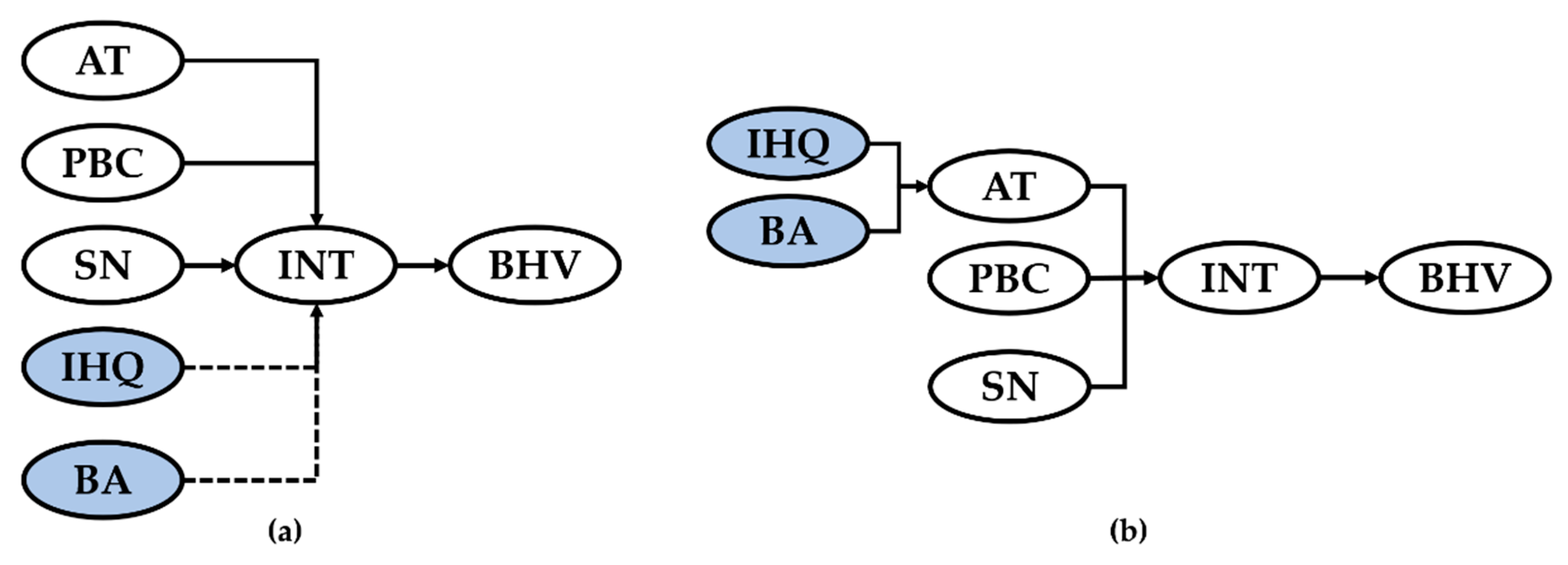

2. Previous Studies and Theoretical Framework

- Inherent Homeowner Qualities (IHQs): Homeowner characteristics, such as income level, education, and age, have been shown to influence decision-making in home renovation and climate adaptation. These variables provide a deeper understanding of the social and economic constraints that impact intention formation.

- Building Attributes (BAs): Structural features of a home, including its current energy efficiency, age, and renovation history, directly affect the feasibility and necessity of climate-adaptive renovations. Without accounting for these attributes, the model would lack critical explanatory power regarding the practical limitations homeowners face.

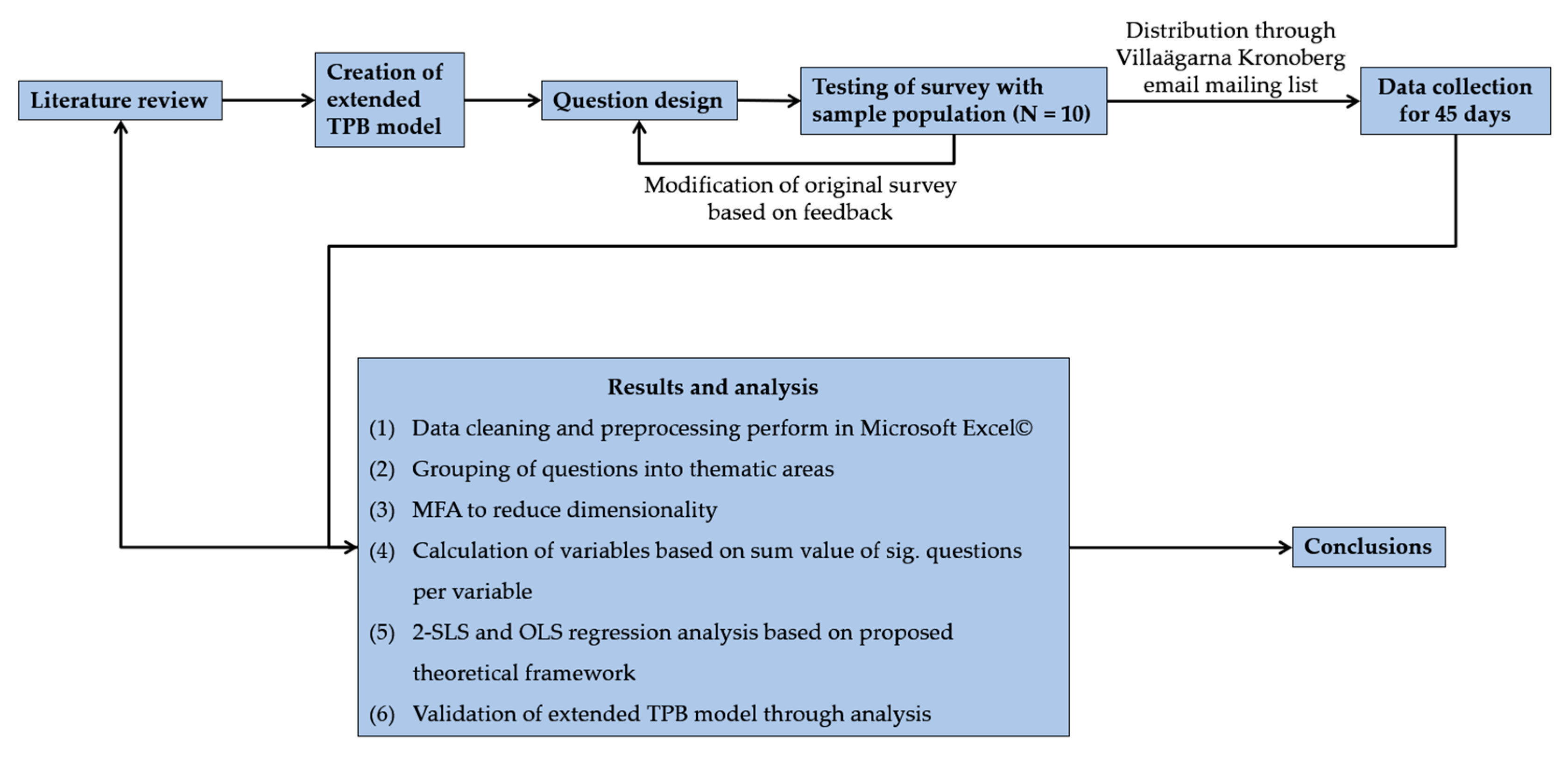

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Aim and Objectives

3.2. Survey Design

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Non-Response Bias

4.2. Results from OLS Regression Analysis

4.2.1. OLS Regression Analysis for All Input Variables and INT

4.2.2. OLS Regression Analysis for IHQ, BA, and AT

4.3. Results from 2-SLS Regression Analysis for All Input Variables and BHV

5. Conclusions

- (i)

- OLS regression for IHQ, BA, AT, PBC, SN, and INT.

- (ii)

- OLS regression for IHQ, BA, and AT.

- (iii)

- 2-SLS regression for all input variables and BHV.

6. Limitations and Further Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPB | theory of planned behaviour |

| IHQ | inherent homeowner qualities |

| BA | building qualities |

| AT | attitude |

| PBC | perceived behavioural control |

| SN | subjective norm |

| INT | intention |

| BHV | behaviour |

| OLS | ordinary least squares |

| 2-SLS | two-stage least squares |

References

- Förordning (2018:1428) Om Myndigheters Klimatanpassningsarbete—Regeringskansliets Rättsdatabaser. Available online: https://beta.rkrattsbaser.gov.se/sfs/item?bet=2018%3A1428&tab=forfattningstext (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Lawler, J.J.; Spencer, B.; Olden, J.D.; Kim, S.H.; Lowe, C.; Bolton, S.; Beamon, B.M.; Thompson, L.; Voss, J.G. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies to Reduce Climate Vulnerabilities and Maintain Ecosystem Services. Clim. Vulnerability 2013, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Tubiello, F.N. Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies in Agriculture: An Analysis of Potential Synergies. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2007, 12, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boende i Sverige. Available online: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/boende-i-sverige/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Kommungränser Sverige—Overview. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=3802c73e277b4019882e639c40e1c353 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Fuel, S.N.; Moberg, A.; Gouirand, I.; Schoning, K.; Wohlfarth, B.; Kjellström, E.; Rummukainen, M.; Centre, R.; Linderholm, H.; Zorita, E. Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB Climate in Sweden During the Past Millennium-Evidence from Proxy Data, Instrumental Data and Model Simulations; Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co.: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tjugo År Sedan Stormen Gudrun Drabbade Kronoberg—Länets Krishantering Sattes På Prov|Länsstyrelsen Kronoberg. Available online: https://www.lansstyrelsen.se/kronoberg/om-oss/nyheter-och-press/nyheter---kronoberg/2025-01-08-tjugo-ar-sedan-stormen-gudrun-drabbade-kronoberg---lanets-krishantering-sattes-pa-prov.html (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Poussin, J.K.; Wouter Botzen, W.J.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Effectiveness of Flood Damage Mitigation Measures: Empirical Evidence from French Flood Disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 31, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieken, A.H.; Müller, M.; Kreibich, H.; Merz, B. Flood Damage and Influencing Factors: New Insights from the August 2002 Flood in Germany. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreibich, H.; Van Loon, A.F.; Schröter, K.; Ward, P.J.; Mazzoleni, M.; Sairam, N.; Abeshu, G.W.; Agafonova, S.; AghaKouchak, A.; Aksoy, H.; et al. The Challenge of Unprecedented Floods and Droughts in Risk Management. Nature 2022, 608, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paprotny, D.; Kreibich, H.; Morales-Nápoles, O.; Wagenaar, D.; Castellarin, A.; Carisi, F.; Bertin, X.; Merz, B.; Schröter, K. A Probabilistic Approach to Estimating Residential Losses from Different Flood Types. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 2569–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ootegem, L.; Verhofstadt, E.; Van Herck, K.; Creten, T. Multivariate Pluvial Flood Damage Models. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 54, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobini, S.; Nilsson, E.; Persson, A.; Becker, P.; Larsson, R. Analysis of Pluvial Flood Damage Costs in Residential Buildings—A Case Study in Malmö. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocklöv, J.; Forsberg, B. The Effect of High Ambient Temperature on the Elderly Population in Three Regions of Sweden. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 2607–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.G.; Hajat, S.; Gasparrini, A.; Rocklöv, J. Cold and Heat Waves in the United States. Environ. Res. 2012, 112, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardalis, G.; Mahapatra, K.; Bravo, G.; Mainali, B. Swedish House Owners’ Intentions Towards Renovations: Is There a Market for One-Stop-Shop? Buildings 2019, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Pardalis, G.; Mahapatra, K.; Mainali, B. Physical vs. Aesthetic Renovations: Learning from Swedish House Owners. Buildings 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- März, S. Beyond Economics—Understanding the Decision-Making of German Small Private Landlords in Terms of Energy Efficiency Investment. Energy Effic. 2018, 11, 1721–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumhof, R.; Decker, T.; Röder, H.; Menrad, K. An Expectancy Theory Approach: What Motivates and Differentiates German House Owners in the Context of Energy Efficient Refurbishment Measures? Energy Build. 2017, 152, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Li, H.; Wang, X.W. Farmers’ Willingness to Convert Traditional Houses to Solar Houses in Rural Areas: A Survey of 465 Households in Chongqing, China. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Cox, A.; Sayar, R. What Predicts the Physical Activity Intention-Behavior Gap? A Systematic Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawang, S.; Kivits, R.A. Greener Workplace: Understanding Senior Management’s Adoption Decisions through the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wens, M.L.K.; Mwangi, M.N.; van Loon, A.F.; Aerts, J. Complexities of Drought Adaptive Behaviour: Linking Theory to Data on Smallholder Farmer Adaptation Decisions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 63, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speelman, L.H.; Nicholls, R.J.; Dyke, J. Contemporary Migration Intentions in the Maldives: The Role of Environmental and Other Factors. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Peden, A.E.; Pearson, M.; Hagger, M.S. Stop There’s Water on the Road! Identifying Key Beliefs Guiding People’s Willingness to Drive Through Flooded Waterways. Saf. Sci. 2016, 89, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D. Disaster Risk Reduction: Psychological Perspectives on Preparedness. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, P.D.; De Ruyck, O.; Saldien, J.; Ponnet, K. Who Wants to Join a Renewable Energy Community in Flanders? Applying an Extended Model of Theory of Planned Behaviour to Understand Intent to Participate. Energy Policy 2021, 151, 112121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Ahmad, S.; Charles, V.; Xuan, J. Sustainable Commercial Aviation: What Determines Air Travellers? Willingness to Pay More for Sustainable Aviation Fuel? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 133990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazart, C.; Blayac, T.; Rey-Valette, H. Contribution of Perceptions to the Acceptability of Adaptation Tools to Sea Level Rise. Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.Z.; Wong, K.H.; Lau, T.C.; Lee, J.H.; Kok, Y.H. Study of Intention to Use Renewable Energy Technology in Malaysia Using TAM and TPB. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borragán, G.; Ortiz, M.; Böning, J.; Fowler, B.; Dominguez, F.; Valkering, P.; Gerard, H. Consumers’ Adoption Characteristics of Distributed Energy Resources and Flexible Loads behind the Meter. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 203, 114745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritu, R.K.; Kaur, A. Unveiling Indian farmers’ adoption of climate information services for informed decision-making: A path to agricultural resilience. In Climate and Development; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, M.; Yousefpour, R. How Do People’s Perceptions and Climatic Disaster Experiences Influence Their Daily Behaviors Regarding Adaptation to Climate Change? A Case Study Among Young Generations. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, S.; Lima, M.L.; Roseta-Palma, C.; Rodrigues, N.; Sousa, L.P.; Freitas, F.; Alves, F.L.; Lillebo, A.I.; Parrod, C.; Jolivet, V.; et al. Psychosocial Drivers for Change: Understanding and Promoting Stakeholder Engagement in Local Adaptation to Climate Change in Three European Mediterranean Case Studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matharu, M.; Jain, R.; Kamboj, S. Understanding the Impact of Lifestyle on Sustainable Consumption Behavior: A Sharing Economy Perspective. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2021, 32, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Dagiliute, R.; Juknys, R. The Determinants of Renewable Energy Usage Intentions Using Theory of Planned Behaviour Approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, K. Klimatförändringar och konsekvenser i Kronobergs län. Länsstyrelsen i Kronobergs Län, Länsstyrelsen meddelande nr 2011:04. 2011. ISSN 1103-8209. Available online: https://www.lansstyrelsen.se/download/18.1b1d393819324610c374b6e1/1732521757467/Klimatf%C3%B6r%C3%A4ndringar%20och%20konsekvenser%20i%20Kronobergs%20l%C3%A4n.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, W.; Li, H.; Guo, P.; Ye, F. Bridging the Intention—Behavior Gap: Effect of Altruistic Motives on Developers’ Action towards Green Redevelopment of Industrial Brownfields. Sustainability 2021, 13, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, P.; Martens, E.; Van Hove, S.; Van Acker, B.; Ponnet, K. Applying an Extended Model of Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Intent to Perform an Energy Efficiency Renovation in Flanders. Energy Build. 2023, 298, 113532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M.; Stok, F.M.; Van Hemel, C.; De Wit, J.B.F. Including Social Housing Residents in the Energy Transition: A Mixed-Method Case Study on Residents’ Beliefs, Attitudes, and Motivation Toward Sustainable Energy Use in a Zero-Energy Building Renovation in The Netherlands. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 656781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.S. Soft Power and Public Diplomacy Revisited. Hague J. Dipl. 2019, 14, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Khoshnevis, M. Conceptualizing Nation Branding: The Systematic Literature Review. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2023, 32, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, D.; Wyer, R.S., Jr. The Cognitive Impact of Past Behavior: Influences on Beliefs, Attitudes, and Future Behavioral Decisions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Godin, G.; Conner, M.; Germain, M. Paradoxical Effects of Experience: Past Behavior Both Strengthens and Weakens the Intention-Behavior Relationship. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Context of Application | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Maldives [25] | Factors affecting migration in response to environmental and socio-economic factors | Based on a modified framework of TPB, it was found that migration was driven by perceived economic gains rather than environmental concerns |

| Australia [26] | Factors influencing the decision to drive through flooded waterways | Based on a modified TPB framework to include a risk perception factor, it was found that while attitudinal beliefs were a significant factor, risk perception played a major role in determining intention. |

| Australia [27] | Effectiveness of different theories when being applied to disaster preparedness | Attitudes and perceived behavioural control influence preparedness intentions; factors from other theories, such as protection motivation and social-cognitive theory, also play a significant role. Trust in authorities, past disaster experience, and community engagement are identified as critical elements in enhancing preparedness efforts |

| Netherlands [28] | Applying the extended model of TPB to understand barriers to people joining a renewable energy community | Attitude and subjective norms were both found to be strong predictors of intent, while perceived behaviour has a significant but modest impact. Additional relationships between attitudes towards renewable energy, environmental concern, financial gain, and willingness to change behaviour and attitude towards renewable energy communities were also found. |

| United Kingdom [29] | Applying the extended model of TPB to understand willingness to pay for low carbon fuel jets (LCFJs) | Social trust, perceived risks, and attitude were the strongest indicators for willingness to pay for LCFJ. Although the overall perception of the benefits of LCJF outweighs the associated risks, the level of awareness of LCJF use was found to be low. |

| France [30] | Applying modified TPB to a survey of coastal populations to analyse property relocation policies in response to sea level rise | Social norms, a perceived sense of control, could help increase the acceptability, and greater trust in policymakers could lead to better acceptance of adaptation strategies. |

| Malaysia [31] | Integration of TPB and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to study acceptance of renewable energy technology | Attitude and perceived behaviour control were important in determining intention to adopt renewable energy technology, while perceived ease of use and usefulness were significant in determining attitudes. Subjective norms were not found to play a role in influencing intentions. The extended model integration, both including additional factors, was found to have greater explanatory power than both TPB and TAM individually. |

| Belgium [32] | Integration of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and TPB to examine the adoption of distributed energy resources by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) | Intrinsic psychological and behavioural factors, such as social norms, hedonic motivation, social influence, and awareness of technology, play a crucial role in driving DER adoption. Meanwhile, extrinsic elements, including financial incentives, ownership structures, and comfort, consistently encourage uptake; however, the adoption of certain DERs is hindered by technological complexities and high costs. |

| India [33] | Application of extended TPB and multistage sampling to analyse farmers’ intention in using climate forecasts for making informed decisions in farming | Positive attitudes toward the reliability and relevance of climate information significantly enhance adoption, while social influence from agricultural peers, local leaders, and government agencies further encourages uptake. Perceived behavioural control, particularly regarding access to technology and literacy levels, presents challenges to adoption. |

| China [34] | Integration of Construal Level Theory (CLT) and TPB to analyse factors that influence adaptive behaviours to drought and water saving | Improving public perceptions of climate change could enhance the perceived attractiveness and motivation for adaptation efforts, while fostering more favourable perceptions of water conservation could improve the perceived practicality and implementation potential of adaptive strategies. Firsthand experience also affected individual behaviours, but the impact was indirect. |

| Portugal [35] | Application of TPB to analyse intentions of participating in adaptation processes for climate change | Stakeholders’ intention to engage was strongly influenced by subjective norms, which were shaped by their normative beliefs regarding policymakers and other stakeholders. Additionally, their perceived behavioural control, driven by their understanding of relevant policies and instruments, also played a significant role in predicting engagement intentions. The workshops carried out as part of the study were effective in affecting intentions to participate in certain processes. |

| India [36] | Application of the lifestyle of health and sustainability (LOHAS) tendency as an extension to understand sustainable consumption behaviour | The LOHAS tendency was confirmed to be an antecedent to attitudes of consumers, which in turn becomes an important predictor for consumer behaviour. |

| Lithuania [37] | Applying TPB to understand determinants of intentions to use renewable energy. | The level of development of renewable energy and financial capabilities of respondents had the most impact on intention to use renewable energy. A significant positive relation was also observed between subjective norms and intention to use renewable energy, but no such correlation was observed between attitudes and intention to use renewable energy. |

| Question No. | Explanation of Question | Possible Responses and Associated Value | Identified Thematic Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q00 | Type of house you live in | Townhouse, semidetached house, detached house, etc. | BA |

| Q01 | Year of birth | >1985 (1), >1975 (2), >1965 (3), >1955 (4), ≥1925 (5) | IHQ |

| Q02 | Highest level of education | IHQ | |

| Q07 | Year the house was constructed | 10-year intervals between 1930 and 2020 (1–11) | BA |

| Q08 | Length of time lived in current house | 5-year intervals between <5 and >20 years (1–5) | BA |

| Q09 | Heated living area of the house | 30 sqm intervals between <31 and >120 sqm (1–5) | BA |

| Q10 | Connection to municipal water system | Yes (1)/no (0) | BA |

| Q11 | Type of heating system used in the house | Different types of heat pumps, boilers, or fireplaces (1–11) | BA |

| Q12 | Primary façade material used | Brick (1), concrete (2), wood (3), or other (0) | BA |

| Q13 | Describing the quality of aspects of the house: Water quality; Air quality; Thermal comfort | Likert scale rating, 1 (very poor)–5 (very good) | ATT |

| Q14 | Past experiences of problems relating to: Indoor humidity or mould; Icicles on the roof; Flooding; Sewage overflow; Drainage; Roof overload; Detachment of exterior siding; Water/air leakage; Poor ventilation; Overheating; Lowered water quality; Structural damage from flooding | Likert scale rating, 1 (no problems)–5 (serious problems) | PBC |

| Q15 | Past renovations in the last 10 years relating to: Façade; Drainage; Sewer; Roof; Windows; Roof insulation; Basement insulation; Outer layer insulation | Likert scale rating, 1 (major renovation)–3 (none) | BHV |

| Q16 | Reasons for carrying out said renovation: Due to ageing/deterioration; Due to damages; To increase safety; To improve energy performance; To save money | Yes (1)/no (0) | PBC |

| Q17 | Party responsible for carrying out said renovations | Owner with help of acquaintances (1), partially with help of companies (2), employed companies independently (3), and employed a general contractor (4). | SN |

| Q18 | Financing of the renovation: Own savings; Mortgage loan; Private loan; Other | Yes (1)/no (0) | IHQ |

| Q19 | Gross annual household income | 150,000 SEK intervals between below 300,000 SEK to more than 750,000 SEK (1–5) | IHQ |

| Q20 | Insurance provider | Alternatives between Sweden’s top 10 insurance providers (1–10) | IHQ |

| Q21 | Have you experienced any damage to any of the following: Façade; Drainage; Sewer; Roof; Windows; Roof insulation; Basement insulation; Outer layer insulation | No (0), yes (due to other reasons) (1) and yes (caused by climate disaster phenomena) (3) | BA |

| Q22 | Knowledge regarding home insurance coverage | Likert scale rating, 1 (know nothing)–5 (know a lot) | IHQ |

| Q23 | Coverage of climate-related damages under home insurance | Yes (1)/no (0) | IHQ |

| Q24 | Impact of climate change on daily lifestyle | Likert scale rating, 1 (none)–5 (severe) | SN |

| Q25 | Plans for future renovations in the next 10 years: Façade; Drainage; Sewer; Roof; Windows; Roof insulation; Basement insulation; Outer layer insulation | Yes (serious renovation) (3), yes (maintenance) (1), and no (0) | INT |

| Q26 | Reasons for planned renovation: Due to ageing/deterioration; Due to damages; To increase safety; To improve energy performance; To save money | Likert scale rating, 1 (disagree)–5 (agree) | BHV |

| Q27 | Who should be held responsible for future damage resulting from a climate-related event/phenomenon, | Myself, the municipality, the County Administrative Board, and the insurance provider | SN |

| Q28 | Previous experience with climate change-related events/phenomena: Heatwaves; Cold waves; Drought; Extreme snowfall; etc. | Yes (1)/no (0) | ATT |

| Q29 | Experience of this phenomenon | Directly, indirectly, or unaffected by it | ATT |

| Q30 | Expected likelihood of climate-related event/phenomenon soon | Likert scale rating, 1 (very low)–5 (very high) | |

| Q31 | Extent of influence of previous experience of climate-related events/phenomena on decisions for major renovation or maintenance of your house | Likert scale rating, 1 (very low)–5 (very high) | PBC |

| Q32 | Need to relocate due to climate disasters in the last 20 years. | Yes (in Sweden), yes (outside Sweden), no | |

| Q33 | Knowledge about climate change and its impacts | Likert scale rating, 1 (very low)–5 (very high) | ATT |

| Q34 | Extent of impact of climate change on surrounding society | Likert scale rating, 1 (very low)–5 (very high) | SN |

| Q35 | Participation in training programmes for climate disaster response/preparedness | Yes (for a long time) (2), yes (recently) (2), no (but I intend to) (1), and never (0) | BHV |

| Q36 | Which of the following climate change-related events/phenomena concerns you the most regarding your house: Heatwaves; Cold waves; Drought; Extreme snowfall; etc. | Yes (1)/no (0) | ATT |

| Q37 | Other climate change-related measures taken: Using energy-efficient bulbs; Purchasing energy-efficient electronic appliances; Using smart heating/cooling solutions; Using renewable energy solutions; Reducing air travel; Reduce, reuse, recycle.; Minimise organic material waste.; Calculate my household’s carbon footprint | BHV | |

| Q38 | Do you take any additional measures to adapt to climate change (multiple options may be selected): Collect rainwater to reduce consumption; Plant trees to create shaded areas; Invest in protective measures for my house; Educate myself to raise awareness about climate change; Planting tree species and forestry practices less vulnerable to storms and fires. | BHV | |

| Q39 | You identify as | Male, female, and other/do not wish to respond | IHQ |

| Q40 | Are you married/cohabiting? | Yes (1)/no (0) | IHQ |

| Q41 | Number of adults (>18 years old); children (13–17 years old); children (<13 years old) living in the house | None | IHQ |

| Variable | Ques. | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| IHQ | Q19 | Annual household income |

| Q41 | Number of adults in household | |

| BA | Q00 | Type of house |

| Q09 | Heated living area of the house | |

| ATT | Q24 | Impact of climate change on daily life |

| Q28 | Experience of climate disasters | |

| PBC | Q14 | Previous experience with damages to aspects of the house |

| Q16 | Reasons for carrying out renovations in the past 10 years. | |

| Q30 | Expected damage to the house in the next 10 years | |

| SN | Q34 | Impact of climate change on society |

| INT | Q25 | Plans to carry out future renovations |

| BHV | Q15 | Parts of the house renovated over the past 10 years. |

| Q35 | Participation in training programmes for climate disaster response/preparedness | |

| Q37 | General climate change-related measures they take. | |

| Q38 | Measures taken to adapt to climate change |

| Age Group (Years) | <39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | >79 |

| Survey | 2.38 | 7.94 | 11.9 | 25.4 | 40.5 | 11.9 |

| SCB data | 14.1 | 19.1 | 20.8 | 21.1 | 16.9 | 8.03 |

| Year house was built | Before 1950 | 1951–1960 | 1961–1970 | 1971–1980 | 1981–1990 | After 1991 |

| Survey | 26.3 | 12.8 | 16.5 | 24.8 | 6.02 | 13.5 |

| SCB data | 38.6 | 8.29 | 15.8 | 22.3 | 6.73 | 8.31 |

| Number of Observations | OLS (INT) | OLS (ATT) | 2-SLS (BHV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 136 | 0.854 | 0.993 | 0.358 |

| 200 | 0.953 | 0.999 | 0.397 |

| 300 | 0.993 | 1.000 | 0.521 |

| 400 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.600 |

| 500 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.680 |

| 600 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.739 |

| 700 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.784 |

| 725 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.808 |

| Variable | R2 = 0.514 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. Error | p-Value | |

| IHQ | 1.090 | 0.842 | 0.198 |

| BA | −0.179 | 0.548 | 0.745 |

| AT | 0.692 | 0.343 | 0.046 |

| PBC | 0.240 | 0.344 | 0.487 |

| SN | 0.395 | 0.678 | 0.561 |

| Variable | Significance Statistics for INT (R2 = 0.47) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | Std. Error | p-Value | |

| IHQ | 1.93 | 0.77 | 0.014 |

| BA | 0.688 | 0.35 | 0.052 |

| Variable | β | Std. Error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IHQ | 0.644 | 0.336 | 0.055 |

| BA | 0.167 | 0.202 | 0.402 |

| ATT | 0.322 | 0.123 | 0.009 |

| PBC | 0.204 | 0.129 | 0.115 |

| SN | 0.036 | 0.245 | 0.883 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinha, S.; Pardalis, G.; Mainali, B.; Mahapatra, K. Exploring Homeowners’ Attitudes and Climate-Smart Renovation Decisions: A Case Study in Kronoberg, Sweden. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073008

Sinha S, Pardalis G, Mainali B, Mahapatra K. Exploring Homeowners’ Attitudes and Climate-Smart Renovation Decisions: A Case Study in Kronoberg, Sweden. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinha, Shashwat, Georgios Pardalis, Brijesh Mainali, and Krushna Mahapatra. 2025. "Exploring Homeowners’ Attitudes and Climate-Smart Renovation Decisions: A Case Study in Kronoberg, Sweden" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073008

APA StyleSinha, S., Pardalis, G., Mainali, B., & Mahapatra, K. (2025). Exploring Homeowners’ Attitudes and Climate-Smart Renovation Decisions: A Case Study in Kronoberg, Sweden. Sustainability, 17(7), 3008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073008