Evolutionary Patterns and Influencing Factors of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism-Dependent Communities Affected by an Epidemic: An Empirical Study in the Wulingyuan Scenic Area, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

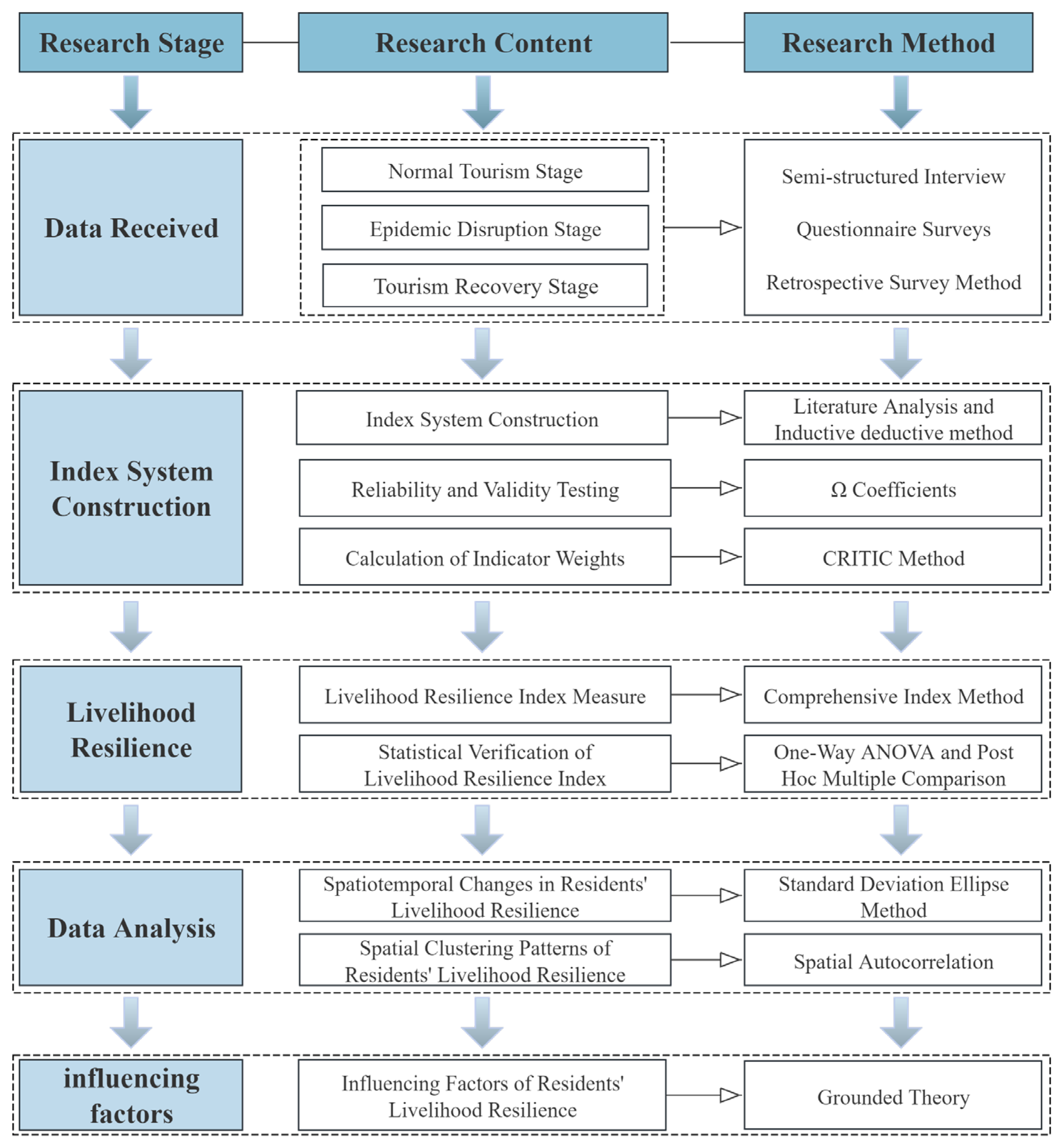

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Data Collection and Sources

- (1)

- Preparation Phase: A literature review was conducted to synthesize existing frameworks of livelihood resilience. Measurement indicators were defined based on prior studies, and both survey instruments and interview protocols were designed.

- (2)

- Preliminary Survey Phase: In November 2023, field research was conducted in relevant departments of Wulingyuan District, Zhangjiajie City, to collect basic data on social, economic, and ecological environments, establishing a research background framework. Subsequently, pre-surveys were conducted in five typical communities within the core scenic area. A random sample of 10–15 households from each community was selected for questionnaire testing. Based on the pre-survey results, the questionnaire design was further optimized, including rephrasing ambiguous questions, deleting redundant questions, and adding new questions to address gaps identified during the pilot survey.

- (3)

- Formal Survey Phase: From January to February 2024, following the route of Longweiba–Luoguta–Yejipu–Sinanyu–Wujiayu, a stratified random sampling method was adopted to select 70–77 households from each community for a 20-day formal household survey. To ensure data representativeness and reliability, collected data subsets were cross-checked for consistency and completeness, and follow-up interviews were conducted to verify data in cases of discrepancies.

2.2.2. Index System Construction and Variable Description

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Assessment of Residents’ Livelihood Resilience

- (1)

- Reliability and Validity Testing

- (2)

- Calculation of Indicator Weights

- (3)

- Comprehensive Index Method

- (4)

- Paired t-test and one-way ANOVA

2.3.2. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Residents’ Livelihood Resilience

- (1)

- Standard Deviation Ellipse Method

- (2)

- Spatial Autocorrelation

2.3.3. Influencing Factors of Residents’ Livelihood Resilience

- (1)

- Open Coding

- (2)

- Axial Coding

- (3)

- Selective Coding

3. Results

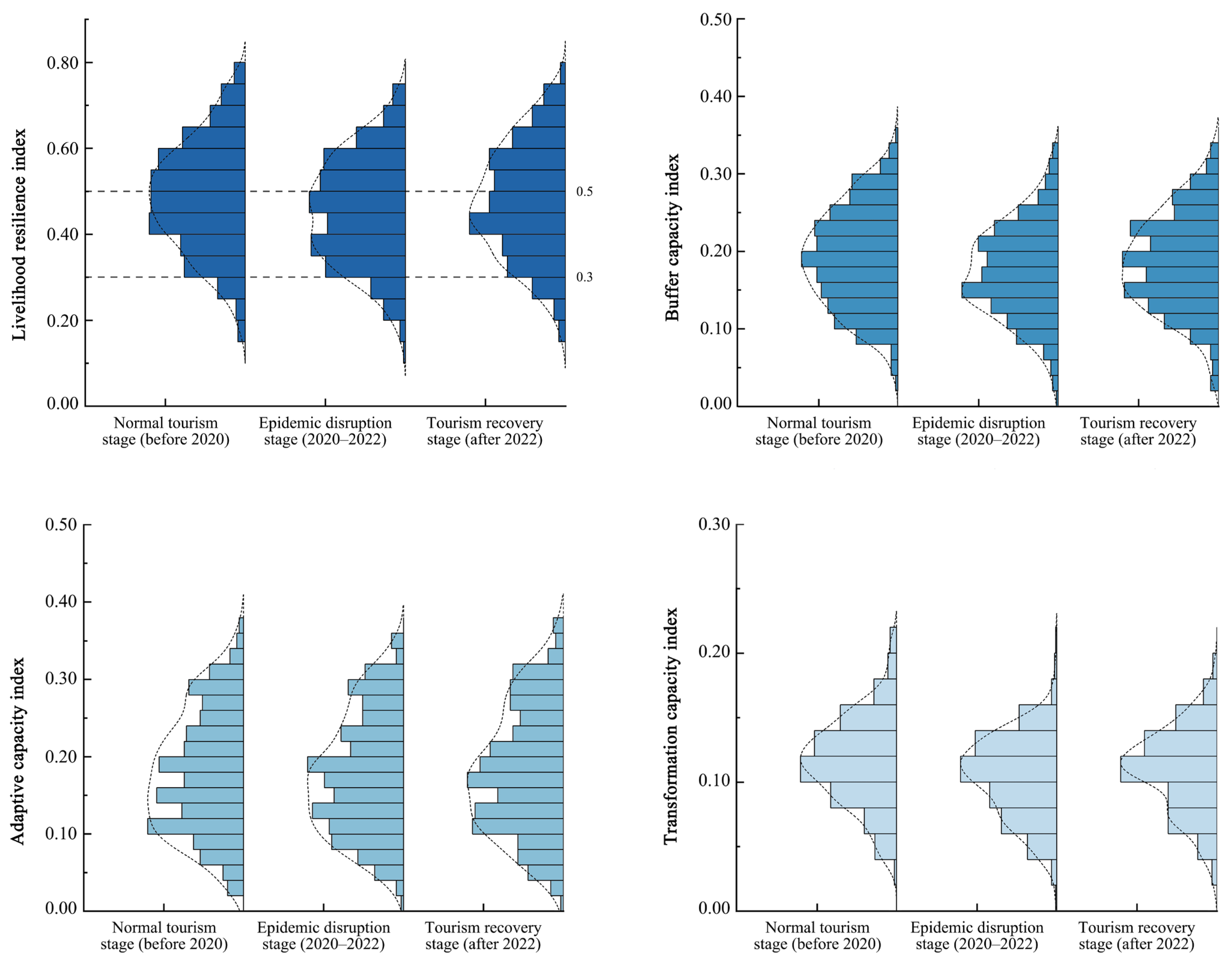

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism-Dependent Communities

Temporal Evolution of Livelihood Resilience

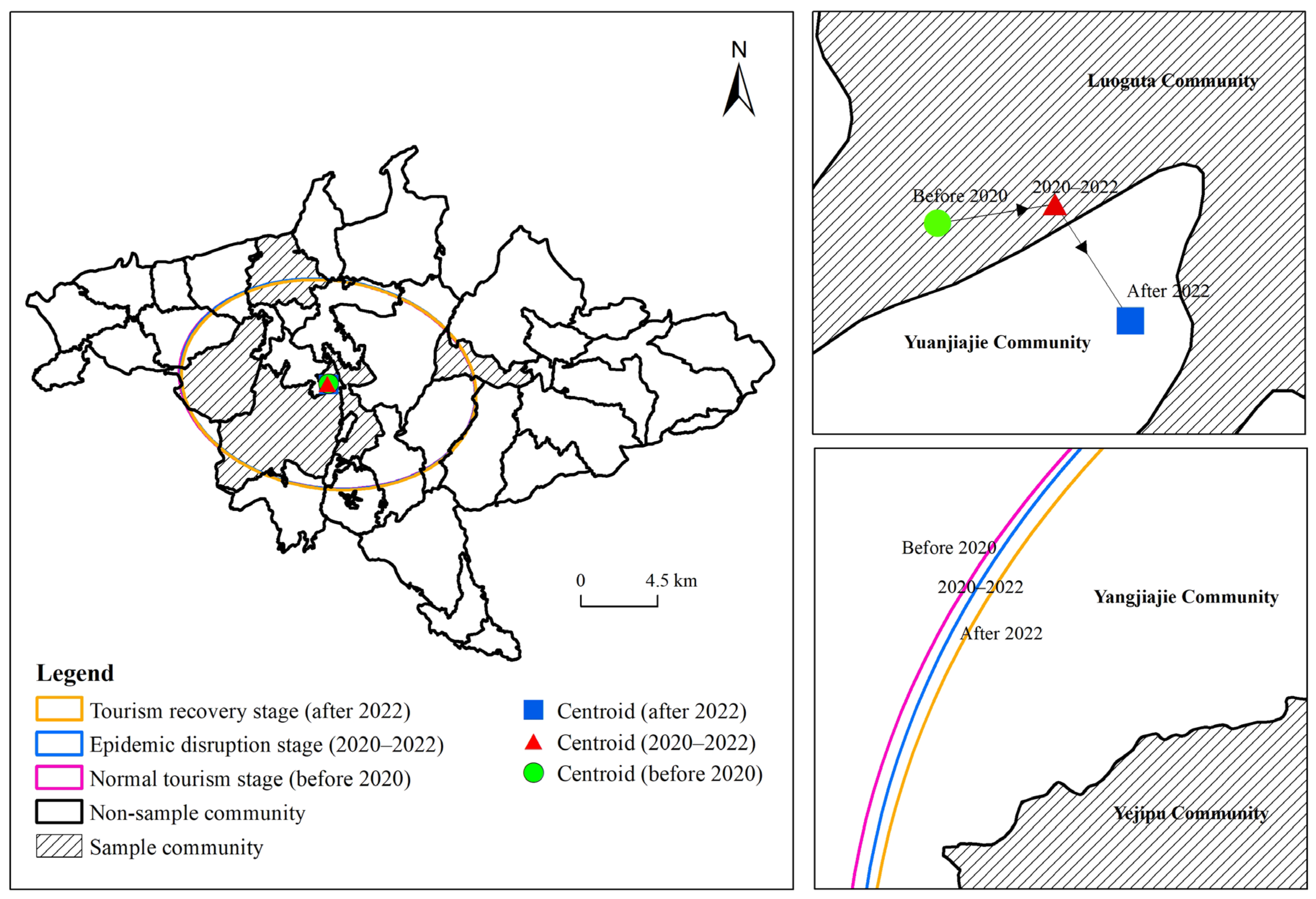

3.2. Spatial Evolution Pattern of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism Community Residents

3.3. Influencing Factors of Tourism Community Residents’ Livelihood Resilience

3.3.1. Livelihood Shock Conditions

- (1)

- Livelihood Vulnerability

- (2)

- Tourism Development Conditions

- (3)

- Livelihood Capital Conditions

3.3.2. Livelihood Coping Strategies

- (1)

- Coping Capacity

- (2)

- Transformation Potential

- (3)

- Psychological State

- (4)

- Relief Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Su, Y. Rural revitalization: A new strategy for Rural development in China. J. Cent. Inst. Soc. 2017, 6, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Srijuntrapun, P.; Fisher, D.; Rennie, H.G. Assessing the sustainability of tourism–related livelihoods in an urban World Heritage Site. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huai, J. Multi-risk assessment of agricultural meteorological disasters based on a three-level hierarchical framework. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1460–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ahmad, A.G.; Barghi, R. Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, A.; Dahles, H. Are tourism livelihoods sustainable? Tourism development and economic transformation on Komodo Island, Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992; IDS IDS Discussion Paper 296. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, S.; Zuo, J.; Yin, N.; Wu, J.; Xie, W. Farmer Households’ Livelihood Resilience in Ethnic Tourism Villages: A Case Study of the Wuling Mountain Area, China. Sustainability 2022, 15, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, C. A study on the adaptability of rural households in traditional villages under the background of rural tourism development: A case study of four villages in Zhangjiajie. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, X. The evolution of livelihood resilience and its influencing factors among poverty-alleviated households in Longnan Mountainous Area. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, T.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Thomalla, F. Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamwanza, A.M.; New, M. Anticipatory adaptation and the role of decadal climate information in rural African livelihood systems Lessons from the Mid–Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2016, 8, 236–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, T.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, T. A study on livelihood resilience and its influencing factors of rural households in the semi-arid region of the Loess Plateau: A case study of Yuzhong County. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2018, 39, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt, A. Measuring livelihood resilience: The Household Livelihood Resilience Approach (HLRA). World Dev. 2018, 107, 253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Huang, X.; Wang, C. Evaluation and optimization strategies of rural household livelihood resilience in the Loess Plateau of Northern Shaanxi: A case study of Yanchuan County. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, W.L.; Wang, Y.; Min, D.; Yang, X. Temporal and spatial evolution law of the decoupling relationship between farmers’ livelihood resilience and multidimensional poverty in ecologically fragile areas: A case study of Jiaxian County, Shaanxi Province. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Gao, M.; Li, S.Z.; Lei, H. The impact of farmers’ livelihood resilience on multidimensional poverty–Evidence from the resettlement areas for poverty alleviation in Shaanxi. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Effects of disaster-related resettlement on the livelihood resilience of rural households in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101649. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, T.N.; Zhou, Z.F.; Niu, Z.H.; Zhang, J.S. Comparison of rural household livelihood resilience before and after relocation for poverty alleviation: A case study of the resettlement site in Zhexiang Town, Zhenfeng County, Guizhou Province. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2022, 38, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, L.; Zhang, P.; Lin, Q. A study on the livelihood resilience of landless farmers in the urban fringe of economically developed regions: A case study of Hangzhou City. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 2047–2056. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L.; Ma, H.Q.; Xi, J.C.; Li, Z.; Li, W. Measuring and analyzing the livelihood resilience and its influencing factors of residents in heritage tourism destinations: A case study of Pingyao Ancient City, Shanxi. Tour. Trib. 2023, 38, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.P.; Zhu, F.B.; Qiu, X.P.; Zhao, S. Effects of natural disasters on livelihood resilience of rural residents in Sichuan. Habitat Int. 2018, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, S.; Zuo, J.; Yin, N.; Xie, W. Evaluation of rural household livelihood resilience and analysis of barrier factors in ethnic tourism villages: A case study of 10 villages in the Wuling Mountain area of Hunan and Hubei. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, J. Technical report on the second round of social and emotional skills assessment of Chinese adolescents. J. East China Norm. Univ. (Educ. Sci.) 2024, 42, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Shi, L.; Zhang, C. Vulnerability assessment and differentiated response strategies of rural territorial systems in counties from a socio-ecological perspective. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, X. A study on the sustainable livelihoods of rural households influenced by rural tourism: A case study of Ankang in the Qinba Mountain area. Mt. Res. 2017, 35, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Nie, L.; Tian, W.; Huang, M.; Qiao, H. Construction and empirical study of a livelihood resilience evaluation index system for rural households in mountainous tourist areas in China: A case study of Enshi Prefecture, Hubei Province. J. Southwest Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 46, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Geng, T.; Shi, Q.; Liu, D. Spatial differentiation and influencing factors of rural household livelihood resilience in the Loess Hilly and Gully Region: A case study of Shigou Town, Mizhi County, Northern Shaanxi. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2020, 36, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 188–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.K. What is the proper way to apply for the multiple comparison test? Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2018, 71, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.A. The interpretation of statistical maps. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1948, 10, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y. Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring organizational resilience: A multiple case study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.-H.; Morrison-Saunders, A.; Grimstad, S. Operating small tourism firms in rural destinations: A social representations approach to examining how small tourism firms cope with non-tourism induced changes. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.B.; Riederer, A.M.; Foster, S.O. The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change-A case study in Mozambique. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2009, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tan, X.; Pan, L. Difference of Farmers’ Livelihood Capital before and after Rural Tourism Development. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 1, 4138220. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H. Can tourism development enhance livelihood capitals of rural households? Evidence from Huangshan National Park adjacent communities, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Huang, Z. Study on the willingness of rural households in nature reserves to change livelihood strategies under the background of ecotourism: A case study of Mount Lu National Nature Reserve. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A. Can tourism contribute to environmentally sustainable development? Arguments from an ecological limits’ perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 8130–8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, R.; Dev, H.S.; Rai, N.D.; Fletcher, R. Rendering land touristifiable: (eco) tourism and land use change. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H. Tourist destination residents’ attitudes towards tourism during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.A.; Fall, K.; Fang, F.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Zhang, W. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak–Corrigendum. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic–A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Yang, Z. The impact of livelihood strategy choices on the stability of rural household poverty alleviation: Evidence from a survey of 1133 targeted poverty alleviation households in the Liangshan Region, Sichuan. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2023, 43, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Gutiérrez, M.; Babri, S. Tourists’ perceptions of economic instruments as sustainable policies in protected areas: The case of Geiranger fjord in Norway. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 39, 100526. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Qiu, S. Measuring and analyzing the livelihood resilience of residents in national park communities: A case study of Pudacuo National Park during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. For. Econ. 2024, 44, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension Layer | Criteria Layer | Index Layer | Variable Description and Assignment | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer capacity | Natural capital | Per capita cultivated land area B1 | 1 = below 67 m2; 2 = 67–201 m2; 3 = 201–402 m2; 4 = 402–666 m2; 5 = above 666 m2 | 0.0776 |

| Financial capital | Annual per capita household income B2 | 1 = below CNY 20,000; 2 = CNY 20,000–30,000; 3 = CNY 30,000–40,000; 4 = CNY 40,000–50,000; 5 = above CNY 50,000 | 0.0625 | |

| Human capital | Proportion of household labor force B3 | 1 = 0–20%; 2 = 20–40%; 3 = 40–60%; 4 = 60–80%; 5 = above 80% | 0.0469 | |

| Number of household members engaged in tourism B4 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 person; 3 = 2 people; 4 = 3 people; 5 = more than 3 people | 0.0480 | ||

| Physical capital | Total household fixed assets B5 | 1 = below CNY 20,000; 2 = CNY 20,000–40,000; 3 = CNY 40,000–60,000; 4 = CNY 60,000–80,000; 5 = above CNY 80,000 | 0.0620 | |

| Social capital | Monthly mobile phone communication cost B6 | 1 = CNY 0–100; 2 = CNY 100–200; 3 = CNY 200–300; 4 = CNY 300–400; 5 = above CNY 400 | 0.0548 | |

| Adaptive capacity | Cognitive ability | Highest education level in the household A1 | 1 = illiterate; 2 = primary school; 3 = junior high school; 4 = senior high school/vocational high school; 5 = college degree and above | 0.0403 |

| Awareness of policies A2 | 1 = 0 types; 2 = 1 type; 3 = 2 types; 4 = 3 types; 5 = more than 3 types | 0.0626 | ||

| Learning ability | Annual household education expenses A3 | 1 = below CNY 2000; 2 = CNY 2000–10,000; 3 = CNY 10,000–20,000; 4 = CNY 20,000–30,000; 5 = above CNY 30,000 | 0.0737 | |

| Opportunities for skill training A4 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 time; 3 = 2 times; 4 = 3 times; 5 = more than 3 times | 0.0493 | ||

| Organizational management ability | Household participation in social affairs management A5 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 time; 3 = 2 times; 4 = 3 times; 5 = more than 3 times | 0.0696 | |

| Number of relatives in public service positions A6 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 person; 3 = 2 people; 4 = 3 people; 5 = more than 3 people | 0.0709 | ||

| Transformation capacity | Policy support | Types of subsidies received by the household T1 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 type; 3 = 2 types; 4 = 3 types; 5 = more than 3 types | 0.0371 |

| Condition of access roads to the household T2 | 1 = farmland road; 2 = branch road; 3 = rural road; 4 = sub-arterial road; 5 = arterial road | 0.0416 | ||

| Transformation path | Degree of financial support T3 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 type; 3 = 2 types; 4 = 3 types; 5 = more than 3 types | 0.0413 | |

| Number of migrant work trips T4 | 1 = none; 2 = 1 time; 3 = 2 times; 4 = 3 times; 5 = more than 3 times | 0.0542 | ||

| Diversity index | Proportion of tourism income T5 | 1 = none; 2 = 0–30%; 3 = 30–60%; 4 = 60–90%; 5 = greater than or equal to 90% | 0.0653 | |

| data | Livelihood diversity index T6 | 1 = 1 type; 2 = 2 types; 3 = 3 types; 4 = 4 types; 5 = more than 4 types | 0.0423 |

| Livelihood Resilience Level | Low | Medium | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index Score | [0, 0.3) | [0.3, 0.5] | (0.5, 1] |

| Category | Concept | Example of Original Statements |

|---|---|---|

| External Changes | Temporary closure of scenic area | “Due to the pandemic, the scenic area had to be temporarily closed. Some tourists had already arrived at the area but were unable to enter”. |

| Internal Threats | Low resilience to external shocks | “Most shops in the picturesque region are modest in size and possess restricted financial resources. In comparison to external firms, the epidemic’s impact is more severe and the capacity for resilience is diminished”. |

| Decrease in Tourists | Low occupancy rate | “The scenic area now rarely receives tourists. The number of visitors during peak seasons has decreased significantly, and many rooms remain unoccupied…” |

| Management Deficiencies | Inadequate infrastructure | “If the management were similar to urban residential areas, with centralized facilities like community hospitals and supermarkets, it would make life much more convenient for both residents and tourists”. |

| Changes in Material Capital | Property construction | “My old house is no longer sufficient for operating a homestay, so I need to build a new house and renovate it”. |

| Lack of Human Capital | Insufficient household labor | “He is ill and can only rest at home, so I am the only one in the family who goes out to sell items for living expenses”. |

| Financial Capital Dilemma | Income–expenditure imbalance | “I invested 200,000 yuan in renovating the homestay, but I have not yet earned back the principal investment…” |

| Organizational Cooperation | Support from relatives | “During the pandemic, it was difficult to find work, so during the peak season, relatives asked me to help manage their shop”. |

| Insufficient Learning Capacity | Low frequency of training | “We rarely organize employment or skills training here, and there are few opportunities for us to participate in such training…” |

| Regional Development Imbalance | Disparities between scenic area and surrounding areas | “People outside the scenic area are operating agritourism and homestays, and their business is thriving. But inside the scenic area, development is restricted, and we can only watch others profit”. |

| Expectation Breakdown | Unforeseen consequences | “We never anticipated that the pandemic would last for such an extended period, and the impact on the business of the scenic area shop has been unprecedented, almost unimaginable”. |

| Positive Attitude | Trust in government | “Notwithstanding the considerable effects of the pandemic on the tourism sector, we assert that post-pandemic, the government will implement policies to facilitate the recovery and advancement of tourism”. |

| Total of 16 Categories | Total of 105 concepts | …… |

| Main Categories | Corresponding Categories | Examples of Related Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Livelihood Vulnerability | External Changes | Temporary closure of tourist attractions, delay in reception of visitors, restrictions on visitor numbers, and operational disruptions |

| Internal Threats | Small-scale operations, traditional closures, resource depletion, low resilience to shocks, limited funding, and high dependency on tourism | |

| Tourism Development Conditions | Decrease in Visitors | Low tourist retention, visitors not staying long, low occupancy rates, reduced number of tourists during peak season, and limited ticket sales |

| Management Deficiencies | Lack of participation mechanisms, restrictions on livelihood activities, conflicts in profit-sharing, insufficient planning, inadequate infrastructure, and changes to scenic spot names | |

| Livelihood Capital Conditions | Changes in Material Capital | Increased participation costs, facility investments, house construction, and renovations |

| Limited Natural Capital | Land acquisition, reduction in arable land, limitations on farming conditions, and wildlife damage | |

| Lack of Human Capital | Insufficient labor, loss of workforce, inability to work, and health crises | |

| Financial Capital Challenges | Unpaid wages, reduced income, income–expenditure imbalance, and low return on investment | |

| Response Capacity | Enhanced Organizational Collaboration | Family support, collective development, material assistance, emotional support, and shared interests |

| Limited Learning Capacity | Insufficient market awareness, limited exposure, infrequent training opportunities, lack of investment in education, and lack of qualified instructors | |

| Transformation Potential | Monolithic Livelihood Strategies | Single-industry livelihoods, limited job opportunities, lack of capital and technology, and restricted livelihood capacity |

| Imbalanced Regional Development | Differences in policy support, disparities between areas within and outside the scenic spots, unequal livelihood opportunities, and income disparities | |

| Psychological State | Disruption of Expectations | Unexpected events, feelings of helplessness, unprecedented situations, unimaginable impacts, and collapse |

| Positive Attitude | Mental adjustment, confidence in tourism development, trust in government support, positive perceptions from tourists, and catering to tourists’ preferences | |

| Relief Measures | Tourism Policies | Suspension of tourism activities, ban on group tours, gradual recovery of individual tourism, and resumption of group tours |

| Marketing Stimulus | Promotions, advertising, price reductions, bundled consumption, discounts, and travel coupons |

| Core Categories | Main Categories |

|---|---|

| Livelihood Shocks Conditions | Livelihood Vulnerability |

| Tourism Development Conditions | |

| Livelihood Capital Conditions | |

| Livelihood Coping Strategies | Coping Capacity |

| Transformation Potential | |

| Psychological State | |

| Relief Measures |

| Stage | Moran’s I | p-Value | Z-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal tourism stage (before 2020) | 0.1273 | 0.0000 | 5.6405 |

| Epidemic disruption stage (2020–2022) | 0.1120 | 0.0001 | 5.6405 |

| Tourism recovery stage (after 2022) | 0.1475 | 0.0000 | 6.5152 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Cao, Q.; Ouyang, W.; Chen, B.; Su, Y.; Xie, W.; Liu, S. Evolutionary Patterns and Influencing Factors of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism-Dependent Communities Affected by an Epidemic: An Empirical Study in the Wulingyuan Scenic Area, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072937

Wu J, Cao Q, Ouyang W, Chen B, Su Y, Xie W, Liu S. Evolutionary Patterns and Influencing Factors of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism-Dependent Communities Affected by an Epidemic: An Empirical Study in the Wulingyuan Scenic Area, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072937

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jilin, Qingqing Cao, Wenwen Ouyang, Bangyu Chen, Yi Su, Wenhai Xie, and Shuiliang Liu. 2025. "Evolutionary Patterns and Influencing Factors of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism-Dependent Communities Affected by an Epidemic: An Empirical Study in the Wulingyuan Scenic Area, China" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072937

APA StyleWu, J., Cao, Q., Ouyang, W., Chen, B., Su, Y., Xie, W., & Liu, S. (2025). Evolutionary Patterns and Influencing Factors of Livelihood Resilience in Tourism-Dependent Communities Affected by an Epidemic: An Empirical Study in the Wulingyuan Scenic Area, China. Sustainability, 17(7), 2937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072937